GURUMAA TIMELINE

1966 (April 8): Gurumaa was born, Gurpreet Grover in Amritsar, Punjab, India.

1980s: Grover completed her secondary education at a Catholic convent school and attended the S.R. Government College for Women in Amritsar.

1980s (late): Grover set out on a solo pilgrimage across north India. She visited sacred pilgrimage sites and sat with many teachers.

1980s (late) 1990s (early): After her sojourn, Grover returned to Amritsar and began to teach in her students’ homes. Her growing body of listeners referred to her as “Swamiji.”

1990s: Swamiji began wearing ochre robes that she had blessed by Sant Dalel Singh, a globally renowned spiritual teacher from Patiala, Punjab, a Nirmala Sikh.

1990s: Swamiji/Gurumaa settled in Rishikesh in a small hermitage near the bank of Ganga (Ganges River). Ardent seekers and devotees began to call her Anandmurti Gurumaa, affectionately simplified as “Gurumaa.”

1999: Anandmurti Gurumaa established the Shakti NGO (non-governmental organization) for the purpose of educating and empowering girl children in India.

1999: Gurumaa began broadcasting her teachings on television on Sony TV and the Aastha Channel (āsthā, meaning “faith”). Satellite technology took her teachings to global audiences.

1999: Gurumaa’s devotees built then-called “Gurumaa Ashram,” known today as Rishi Chaitanya Ashram, in Gannaur, Haryana, which as of this writing remains Gurumaa’s sole residence and teaching center.

2008 (March): Gurumaa participated as one of many “key leaders from India” in the GPIW (Global Peace Initiative of Women, a convening organization which began in 2002 as a UN summit group) program in Jaipur, Rajasthan along with female dignitaries and religious/spiritual leaders from around the world.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Anandmurti Gurumaa is a north Indian based global guru, a charismatic speaker and singer. As the leader of a group of loosely formed spiritual seekers from around the world, though primarily India, she does not consider herself a “founder.” Although Gurumaa has not founded a new “yoga,” “math,” or school of teaching, she certainly has a rapidly developing spiritual movement growing around her. For the purpose of establishing Anandmurti Gurumaa’s ashram, teaching mission and social service initiatives as non-profit in both India and the United States, named entities have been created. It could be said that Gurumaa is the “founder” of these organizations, but these names do not serve as identifiers for the spiritual movement itself. Nonetheless, this article will treat Gurumaa as the “founder” of the “movement” of seekers and devotees surrounding her. Several scholars have debated the veracity of the term “movement.” Religious Studies scholar, Amanda Lucia provides a summary of this problematic term and rationale for its continued use in her recent monograph on global guru, Mata Amritanandamayi (Lucia 2014).

Anandmurti Gurumaa was born Gurpreet Grover to a keshdhari (hair-keeping) Sikh family of Amritsar, Punjab on April 8, 1966. Much of the biographical information we have about Gurumaa comes from internally published materials and oral devotional narratives circulating among her devotees. According to these hagiographic accounts, from an early age, Grover showed an exceptional interest in spirituality, impressing religious teachers from multiple traditions, including the officials in the Catholic girls’ school she attended, as well as the pluralistic array of saints that her parents welcomed into their home. Devotees tell of Grover, as young teen, teaching her peers under a tree on the school grounds. As a child, she and her mother frequently studied with a householder guru in Amritsar, referred to by Gurumaa as “Maharaj ji.” “Maharaj ji” was a pupil of an internationally known Nirmala Sikh teacher, Sant Dalel Singh, who would eventually become Gurumaa’s guru.

Though Gurumaa regards herself as Sant Dalel Singh’s devotee, she did not spend much time with him, and she does not stand in his lineage today. She had brief yet direct and dynamic encounters with him, accepted his grace and charted her own path. Grover left her college studies to set out on a solitary journey across north India, visiting pilgrimage centers, sitting with teachers of various spiritual traditions and lineages. After three or four years, she returned to Amritsar, wearing white clothing, refused societal pressures to marry, and spent all of her time engaged in spiritual practices and teaching, while living in the home of her parents. Many of Gurumaa’s first teaching engagements were given during the workday in the homes of her female students who were homemakers, who began to call her “Swamiji.” Swamiji’s group of followers began to grow, and she needed her own space. She took ochre robes to Dalel Singh for his blessing and then she moved back to Rishikesh, one of the pilgrimage sites in which she had stayed during her sojourn, and with one or two key followers, she set up a small hermitage near the river Ganga. Her students kept coming, and in the 1990s, it became clear that Gurumaa’s humble abode in Rishikesh could no longer accommodate the crowd of followers surrounding her and another location would need to be found. By the late 1990s, Gurumaa’s devotees purchased land in Haryana and transformed that land into (then-called) “Gurumaa Ashram,” known today as Rishi Chaitanya Ashram.

By the end of the 1990s, much through the efforts of her growing body of disciples, this young woman from Amritsar, Anandmurti Gurumaa, was poised to become a twenty-first century guru, with a television show named Amrit Varsha (meaning, “rain of immortal nectar”), a non-governmental organization (NGO) funding the education of underprivileged girls, called Shakti, and a sparkling new ashram in Haryana with enough land to accommodate further growth. Her internal publishing house created books, periodicals and cassettes, reproducing her public teaching sessions into commodities that could be purchased by seekers eager for them.

In the 2000s and 2010s, Gurumaa’s reach has expanded exponentially through her embrace of new media forms. Her internally produced website, gurumaa.com, has taken numerous incarnations in attempt to keep up with the latest technological advances and serve greater numbers of devotees, meeting their demand for the teachings, as well as to attract new seekers. Gurumaa’s YouTube channels now show Amrit Varsha episodes that were previously available only through satellite television channels. Her social media profiles provide links to the latest links of songs and teachings. Gurumaa’s “tech team” led by her senior most disciples and peopled with youthful IT-savvy devotees, creates media output and manages her social media. Sometimes, however, Gurumaa makes her own posts on facebook. The growth of the movement has also resulted in a greater number of girls who receive tuition for their education. Each year the number of Shakti scholarships for girls attending secondary schools has grown and new funding measures have been created to educate girls in vocational schools and in colleges, under the umbrella of Gurumaa’s Shakti NGO.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Raised in a Sikh family, educated in a Catholic convent school and understood to have attained her enlightenment in Vrindavan, the famous Hindu pilgrimage site of Lord Krishna’s divine play, Anandmurti Gurumaa refuses self-identification with any particular religious tradition, or “ism,” yet her teachings draw from many. She eschews religious belonging in favor of a “spirituality beyond boundaries.” Retelling her story from an incident in which Hindu and Sikh officials in Kanpur objected to her teaching at a mandir one night and a gurudwara the next, Gurumaa objects to being labeled by any religious identity:

You may not even know the names of all of them [religions of the world]. Even if you name all of them one by one and ask me if I belong to any of them, my answer will still be in the negative…. In the same way, I am only ‘love’; wherever I find love, those people are mine and I belong to them. And so I am Hindu, a Muslim, a Sikh, A Buddhist, A Jew and Jain; I am everything; I am all of these because I am none of these (Gurumaa 2010:37).

Bucking the status quo in many ways, Gurumaa also refuses to categorize her own brand of renunciation. She quit wearing the ochre colored robes, a color worn not only by Hindu renunciants (sannyasis) but also by the pluralistic Nirmala Sikhs. She continues to wear the color often, but also wears clothes of other colors, according to her moods, and enjoys keeping people guessing about her identity with her dress and her unusual forehead marks (Rudert 2014). Neither does Gurumaa allow her full time ashramites to call their path sannyas, though they do practice a fluid form of renunciation. She encourages her devotees to engage in practices that may feel alien to their inherited religious sensibilities, asking Sikhs to chant Hindu mantras and Hindus to practice the Sufi repetition of “Hu.” She has introduced her listeners to the teaching and stories of sants from different religious traditions of the subcontinent, practicing an intrareligious pluralism derived from the wisdom of multiple traditions while not being “bound” by any of them.

Rudert contends that Gurumaa’s eclectic canon contributes to an understanding of her as a contemporary sant, following in the footsteps of her forbears like Guru Nanak, Kabir, and other north Indian poet singers who valued direct experience, guru devotion and singing of devotional songs over institutionalized religion (Rudert 2017). Also like the north Indian sants and Sufis who sang in Hindi and Punjabi languages, Gurumaa preaches to a religiously plural audience, made up primarily of Hindus and Sikhs but including Jains, Christians and Muslims. She speaks a great deal about universal topics and concerns, and, like her sant forbears, speaks often about death and its immanency, as a way to inspire spiritual hunger in the hearts of her listeners.

Even when not identified by “ism”s, Gurumaa and many of her devotees are deeply engaged in the “traditional” path of Guru-devotion (guru-bhakti), which has a rich and long history in the Indian subcontinent, not limited to the Hindu tradition. The song and story of the sants Gurumaa has engaged so frequently with express the guru-bhakti quite eloquently. The path guru-devotion is understood as a viable method for attaining liberation. Gurumaa celebrates the sant tradition today by singing the songs of these medieval poet-singers and adding to the collection hundreds of her own songs. Like the sants, Gurumaa uses song to tune her listeners’ hearts and minds before she launches into her preaching. Gurumaa launches many of her discourse topics right from the song of a sant, adding contemporary observations to her forbear’s wisdom.

Like the sants, Gurumaa’s teachings draw from an array of wisdom traditions. She has given extensive multi-day (sometimes multi-year) discourses on the Bhagavad Gita, Shankaracharya’s hymns, Kabir’s songs, Guru Nanak’s Japji Sahib, Guru Govind Singh’s Dasam Granth, and notably, she has extended her repertoire to include wisdom originating outside of the Indian subcontinent to sing and preach about Rumi’s songs. In the continued growth of Gurumaa’s eclectic canon we see her lifelong love for learning. We also see in her an inclusivity, consistent with her refusal to adopt a label yet one that expresses appreciation for love in its many forms.

Gurumaa’s seekers who consider themselves guru-bhaktas (devotees of the guru) demonstrate their devotion to the guru in many individual ways, and many regard her as their primary or favorite divinity (iṣṭa deva) and think of their guru as the Divine Teacher (gurudev). Gurumaa’s own songs and the songs of sants she sings reaffirm this stance of the devotee whose attainment is due to the grace of the true guru (satguru). Her devotees regard her as satguru and refer to her as Gurudev. Ashramites and ashram visitors alike greet one another with folded hands and the salutation “Jai Gurudev” in celebration of their guru, whom they understand to be a living embodiment of divine truth.

Finally, Gurumaa, Gurumaa’s teachings are replete with references to and advice for contemporary living. The mistreatment of women and girls, the problem of female feticide, and the need for girls’ education are hot topics for Gurumaa, about which she spends a great deal of time in her public discourses. Though she does not consider herself a social service oriented guru, she felt compelled to create more opportunities for girls’ education in India and the need to put her money toward this aim when she established the Shakti NGO. Each year, she brings to her ashram the recipients of her education grants. While in her ashram, girls and their chaperones attend trainings in meditation and postural yoga, and spend time with Gurumaa.

Disciples claim that Gurumaa lambasts religious traditions for their mistreatment of women, and her talks that have been recorded in books and other media confirm this. She spares no tradition, calling religion a “male bastion.” Discussing a book, titled Shakti, developed from Gurumaa’s discourse on women, Rudert writes:

[Gurumaa] contends that historically male “so-called caretakers of religion and duty” willfully interpreted scriptures to keep women down by continually telling them, “‘Because you are a woman, [you] are impure, therefore, you will never gain knowledge. You will not attain salvation.’ What madness is this!” (Rudert 2017, quoting from Gurumaa 2006:43-44).

Even the Sikh tradition to which she was born, which does not exclude women from the possibility of absolute liberation, Gurumaa claims has not progressed in its ethos of gender equality to include women as leaders in the mainstream tradition. Gurumaa talks at length to her audiences about how to raise independent, educated young women who can make their own choices about marriage. She regularly criticizes her audiences for the lenient treatment of sons, privileging and indulging young boys to the point of spoiling them. She talks of marriage between men and women as an equal partnership in which each should refer to the other respectfully with the honorific “ji”.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Much like her Hindi poet sant forbears, Gurumaa is not much of a ritualist. However, the routine of yogic sādhana performed daily in Gurumaa’s ashram is a form of ritual, or better stated, it is spiritual discipline and practice. Days begin early in the ashram with bathing encouraged at 5:00 AM. Morning āratī begins at 5:30, followed by postural yoga (āsana), then breathing exercises (pranāyama), and meditation (dhyāna), all before breakfast. Meals are taken in the dining hall, Anapurna, named after the goddess of food and bounty. Though the dining hall bears the name of a Hindu goddess, the Sikh langar style of dining presides, in which devotees sit to take food together, regardless of caste and gender distinctions. After breakfast, full-time ashramites and visitors alike go to their jobs (sevā) in order to serve the ashram in some capacity. Mid-morning, Gurumaa offers darshan. After lunch many people take a short rest, work again before dinner and attend the evening meditation session, in the “hut” suitably named Patanjali, after the author of the Yoga Sutra. After dinner, everyone in the ashram participates in evening āratī and then mantra repetition (mantra-japa). Slight variances occur in the schedule due to seasonal change, special activities or retreats happening in the ashram, but the day-to-day schedule represents a dedicated ritual of yogic sādhana, one that Gurumaa encourages her visitors to replicate in their own ways at home.

In the sant tradition, guru devotion’s efficacy as a method for liberation trumps religious ritual involving temples and offerings. Therefore, guru devotional movements in some ways turn ritual on its head. In guru-bhakti, ritual continues, but ritual is directed towards the guru. For most devotees, darshan of Gurumaa is the most significant ritual moment of the day or for their entire ashram visit. In guru-devotion, worship becomes worship of the guru. Pilgrimage can be a journey to the guru’s ashram. And the calendrical festival, Guru-Purnima, could easily be the celebration of the year to a non-ritually inclined guru-bhakta.

Rishi Chaitanya Ashram [Image at right] celebrates a number of calendrical festivals throughout the year. These celebrations draw large numbers of spiritual seekers to the ashram, long-time devotees and first-timers alike. Popular festivals celebrated in the ashram include: Maha Shivratri, Holi, Gurumaa’s birthday celebration, Sanyas Diwas (celebrates Gurumaa’s taking of the ochre robes), Navratri/Durga Ashtami, Guru Poornima, Krishna Janmasthami, Diwali, and Gurpurab (gurumaa.com).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

In the late 1990s, devotees of Gurumaa acquired land, funded and built an ashram for her in Gannaur, Haryana, approximately sixty km from Delhi on the major National Highway 1, a bustling interstate crossing India from Kolkata, through Delhi, on to Amritsar and Lahore. During the years of transition from the Rishikesh hermitage to Gannaur ashram, Gurumaa lived in Delhi and continued her teaching in numerous locations in India. Through her disciples’ initiatives, Gurumaa’s teachings were spread through the media of radio, television and Internet. These teachings attracted followers from all over India, and eventually, near the turn on the millennium through the medium of satellite television, outside of India as well. At the request of seekers, Gurumaa began to travel yearly to the U.S. and U.K. Today, Gurumaa’s teachings continue to be aired on television, but importantly, they are now also broadcast on her website and YouTube channels. Members of Gurumaa’s “tech team,” once housed in Delhi, now live in her Gannaur ashram, keeping all activities of her trust “in house” where she can easily oversee them. Clear helpers and leaders have emerged from Gurumaa’s close circle, but ultimately she makes all of the decisions for her growing organization.

In India, Rishi Chaitanya Trust is the financial entity under which Gurumaa’s home and retreat center, Rishi Chaitanya Ashram, functions. At its inception, Gurumaa was established as the head of this Trust. In the United States, the 501C-3 organization, New Age Seers, Inc., was established by Gurumaa’s American disciples to support Gurumaa’s Shakti NGO in India and her yearly tours to North America, allowing her to offer her teachings to the public without charge.

Gurumaa’s students come to her primarily from urban centers, cities large, medium and small, and the majority come from the Indian middle class. Gurumaa intentionally visits medium sized cities in India and sometimes, particularly in Punjab, visits small cities where she says other gurus do not bother to visit. Gurumaa’s English, perfected during her years of English medium education, allows her to spread her teachings broadly. She teaches primarily in Hindi language (the world’s fifth most spoken language) but sometimes in English, particularly when traveling abroad, and often teaches with a mix of the two languages. Students from around the world have now begun to visit Rishi Chaitanya Ashram, where they can immerse themselves in full days of yogic practices (sadhana), while being in the presence of their beloved guru (gurudev). The ashram’s location makes it accessible; it sits at an easy travel distance from New Delhi, Amritsar, Rishikesh and Haridwar. The ashram’s serene environment buzzing with bees, songbirds and devotees’ mantra repetition, along with clean air, flowers and fresh food grown in its gardens, has proven popular among Gurumaa’s devotees, many of whom visit regularly to perform service to the guru (guru-sevā) through ashram upkeep, to be in her presence and “recharge [their] batteries” by imbibing her contagious energy.

ISSUES/ CHALLENGES

Long term continuity presents a particular challenge for a loosely formed organization around a charismatic leader not aligned to any “ism” or even to any lineage. Gurumaa’s stated intention in her multiple borrowing of practices and teachings from various traditions is to be able to open more minds and hearts. She wants to appeal to the greatest number of people. This stance will and has also invited criticism from detractors who see her as opportunistic, variably teaching to Hindus and then Sikhs to woo moneyed seekers from different stripes. Others dislike the blurring of boundaries of their treasured religious traditions. Yet, Gurumaa’s ability to stand independently, without the institutional sanctioning of any one religious tradition or clan, affirms the Indian spirit of and appreciation for “direct experience” of formal religious training or belonging.

Gurumaa has stated that she will not name a successor and that she is not establishing a lineage (parampara). Gurumaa claims that issues arise in religious groups because the followers of enlightened teachers (disciples who themselves are not enlightened) interpret the teachings to suit their own minds of inferior understanding. However, without a successor, one challenge any movement around a charismatic teacher arises when that teacher ages or passes away. What will become of the movement after its Gurudev is gone? Will the legacy of her Shakti NGO continue? Time itself may challenge the guru’s intention and she may find herself one day in need of a successor or other official leader.

IMAGES

Image #1: Photograph of Gurumaa.

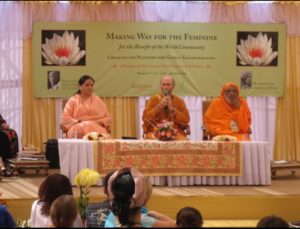

Image #2: Photograph of Gurumaa with David Frawley and Swami Dayananda Saraswati at a Making Way for the Feminine event.

Image #3: Photograph of the Rishi Chaitanya Ashram.

REFERENCES

Gurumaa, Anandmurti. 2010. Rumi’s Love Affair. New Delhi: Full Circle-Hind Pocket Books.

Gurumaa, Anandmurti. 2008. Shakti: The Feminine Energy (Revised Edition). Delhi: Gurumaa Vani.

Gurumaa, Anandmurti. 2006. Shakti. New Delhi: Gurumaa Vani.

Rudert, Angela. 2017. Shakti’s New Voice: Guru Devotion in a Woman-led Spiritual Movement. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

Rudert, Angela. 2014. “A Sufi, Sikh, Hindu, Buddhist, TV Guru.” Pp. 236-57 in Religious Pluralism, State and Society in Asia, edited by Chiara Formichi. London and New York: Routledge.

Post Date:

26 February 2018