GLORIAVALE TIMELINE

1926: Neville Barclay Cooper was born.

1947: Cooper, who was twenty-one married his first wife, Gloria, who was fifteen.

1950: Cooper (later, Hopeful Christian) became an evangelist in Australia.

1967: Cooper traveled to New Zealand as an evangelist.

1969: Cooper lead a schism in the New Life Church in Rangiora.

1971: A Christian school was founded at Springbank farm near Rangiora.

1977: The Christian Community Church of Springbank founded.

1987: The Hutterites visited the Springbank church.

1991: Cooper’s first wife, Gloria, died.

1991: The community purchased a new site for Gloriavale at Haupiri Valley, on the West Coast.

1993: Cooper was charged by the police with sexual offenses.

1995: Sale of the Springbank church was completed.

Mid-1990s: Neville Cooper adopted a religious name, Hopeful Christian.

1995: Hopeful Christian was convicted of indecent assault and given a four-year sentence. David Courage served as acting chief shepherd during Hopeful Christian’s incarceration.

2008: A branch community of Gloriavale was founded in India.

2015: The Charities Services investigated Gloriavale.

2018: Hopeful Christian died.

2018: Three independent trustees were appointed to the Trust.

2020: Police Operation Minneapolis identified sixty-one young individuals as victims or perpetrators.

2022: An apology for the abuses was provided to news media.

2022: The Employment Court ruled that the ex-members of Gloriavale had been employees.

2023: Howard Temple was charged with illegal sexual acts.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

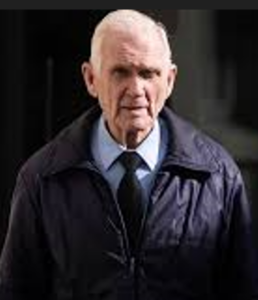

Neville Barclay Cooper was born around 1926, the son of a fruitshop owner. [Image at right] He served as apprentice panelbeater and airforce trainee during the closing days of World War I. He was converted at age twenty-one and then became an evangelist in a separatist Pentecostal group. He married his first wife, Gloria, when he was twenty-one and she was sixteen. Faith was born in 1952, followed by another fifteen children. He became a preacher when he was twenty-three, and established a tent mission “the Voice of Deliverance,” which continued for fifteen years. The growing family lived in a caravan for a period of time. From 1959-1962 they were based in Maryborough, north of Brisbane, and were supported by a church there before moving first to Brisbane, and then in 1965 to Cairns. Cooper undertook a three-month evangelistic tour of New Zealand in the early 1960s as part of the Latter Rain movement, and then moved the whole family to New Zealand in 1967. There he lead evangelistic campaigns within the embryonic New Life Movement. Cooper reportedly lived among Māori people on a marae for a time (Royal Commission 2022:90). Perhaps it was here or somewhere else in the North Island that he served briefly as pastor; he then moved to Rangiora in the South Island, outside of Christchurch. (Royal Commission 2022:41-42; Beale 2009:11-22). In 1969, he broke away from the New Life Movement after tension with the local New Life pastor (Tawara 2017:11-12).

Neville then preached at the St John Ambulance Hall and gathered his first adherents. In 1974, Naomi and Judah Benjamin (Australians who had trained at Faith Bible College in Tauranga) joined the ministry team. Already the group was characterised by modest dress and conservative attitudes and was attracting some notoriety as the “Cooperites.” Faith, the eldest daughter, married Alan Harrison, a teacher, in 1970. Harrison’s family owned property at Springbank, 17 km out of Rangiora and near Cust, and Alan and Faith settled there. When Alan’s parents retired, the couple purchased the property, and they set up a Christian school there. Initially there were initially just twelve students, but others joined, and soon a secondary department was established. Then in 1976, the whole Cooper family moved to Springbank, living on the family homestead, while Faith and Alan built another house. Christmas houseparties were held, and gradually communal living developed, with the initial group of about thirty rising to seventy-five, with each family occupying two bedrooms and singles living in dormitories with a shared kitchen and laundry. (Royal Commission 2022:41; Beale 2009:26-29). Communal life became increasingly regimented, and the community attempted to be self-sufficient. The community became well known in the 1970s for their preaching in Cathedral Square in Christchurch and the instant move of converts into the community. People from Australia, Switzerland, Germany, England, Greece, Canada, and the U.S. and India were attracted to the community (Hostetler 1987).

In 1977, the Christian Church at Springbank was formally established. Some dropped out in the face of the strict rules on dress and women’s role. Among the questioners were Alan and Faith Harrison, and the Benjamins, while Neville’s eldest son Phil, who had fled to Australia, was persuaded to come back. (Beale 2009:32-34). The community became financially successful through manufacturing water beds (Beale 2009:46, 54). Phil Cooper managed this business but became dependent on credit from an outsider. The result was a financial crisis.

Faith and Alan left the community in 1979, even though they owned the land on which the community was based. (Beale 2009:39-41). They frequently reached out to help others who decided to leave, but the strict rules meant that families broke up, as when Judah Benjamin left (Beale 2009:50). Phil left again, and when his wife would not leave, he kidnapped his five children (Tarawa 2017).

Neville Cooper studied the Anabaptists, Amish, Mennonites and Hutterites. In 1987 members of the Bruderhof were invited to visit, and a group of thirty Cooperites visited one of their American communities. (Hostetler 1987; Beale 2009:57-58). But relationships between the two groups cooled as the Cooperites became ever more separatist.

The decision to move to new property at Haupiri in an isolated part of the West Coast of New Zealand’s South Island was taken because of the growth of the community to about 200 people. 917 hectares were purchased. [Image at right] At Haupiri four multi-storied hostels were built, and the first one was opened in 1999. (Tarawa 2017:16). In 1991, the Christian Church Community Trust was registered. It became very active in dairying deer farming and had six associated companies. It did not receive any welfare benefits or borrow money, and was therefore separate from most state control.

Neville’s first wife Gloria died of a brain tumour in March 1991 (Beale 2009:70); his second wife, Anna, died in 1994 at age eighty. He then married a seventeen year-old the following year. Meanwhile community members had begun adopting Christian names; Neville Cooper became Hopeful Christian.

Sexual practices within the movement emerged as an issue around this time. Hopeful’s son, Phil, presented himself as one of his father’s sexual abuse victims and initiated criminal charges against him. In 1995, Hopeful was tried on eleven counts, including offending against a female member of the community in 1984. (Beale 2009:152-53). Upon appeal, the crown narrowed the charges to three, and so although sentenced to four years in prison, he served only eleven months. (Beale 2009:355). The community was not informed about the basis of the convictions and interpreted the case as state-based persecution. In fact, the charges against Hopeful strengthened the loyalty of the community (Tarawa 2017). One member who asked for details was promptly expelled. When Hopeful returned, he did not immediately resume leadership of the community, but after a few weeks had a revelation and resumed his position (Beale 2009:157).

The community grew significantly over the next ten years, both from new adherents and from a large number of children. Families lived in large community houses. At its height the community numbered some 600 people in about ninety families. There were thirty to thirty-five newborns every year (Hurring 2021:28). The growth of the community led it to open a branch in India in 2008 under the leadership of an Indian member who had joined the group and had married one of the original family members.

Gloriavale lost its leader in 2018 when Hopeful Christian died at age ninety-one. Howard Temple, (Image at right) who was seventy-eight, succeeded him as chief shepherd. Temple was a U.S. citizen who had served in the Navy and was part of the McMurdo expeditions to Anarctica. He had married a New Zealand woman, and was discharged in New Zealand in 1964. He joined the Gloriavale community in 1970, and ran the community’s motor repair shop. He became a shepherd in 1985. In that role, he supervised the Indian community and spent half of his time there. (Royal Commission 2022:35). Temple became involved in later investigations of sexual and physical abuse in the early 2020s (See, Issues/Challenges)

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Gloriavale has a statement of belief (an abbreviated version is available on its website). “What we believe,” which was first written in 1989 by Hopeful Christian and Fervent Stedfast (Royal Commission 2022:31, 45). Their beliefs are clustered under four headings. Under the heading, “salvation” they profess that the King James Version is the infallible word of God, a six-day creation, the fall, Noah’s flood, the irrelevance of the Old Testament, the rapture will be followed by the tribulation, the millennium, heaven or hell. Salvation requires faith and obedience to Christ’s commands, forsaking everything for Christ. They are Calvinist as regards predestination, but they adopt an Arminian position about the risk that those who fall away will lose their salvation and specify different roles for men and women.

Their doctrine of the Christian life requires the believer to be free from sin, but makes provision for confession and restoration from sin. They look for perfection of spirit, but acknowledge that we do not possess perfection of knowledge. They expect a distinct experience of being filled with the Spirit subsequent to conversion. Separation from the ways of the world includes prohibitions on smoking, drinking and immodest clothing, while games and music are allowed. Sharing of goods is expected, and believers should never be in debt, while surplus money should be given away. Christians are required to keep the law, pay tax, and make provision for future needs, but should never seek public office. Birthdays and the church calendar are not observed, and there is no mandate to keep the sabbath day. Medicine and hospitals are accepted. Ethnicity and culture has no place in the church. (Tarawa 2017:198-201).

Their doctrine of the church identifies the Roman Catholic and Protestant state churches as the harlot church. The true church must leave behind these traditions, and ideally should hold all their goods in common. The true church needs to practice strict discipline against evil, and must excommunicate heretics and those whose lives do not honour the gospel. Leadership is entrusted to men whom church members recognise and honour. Women are to be submissive towards male leaders. Denominational labels are wrong, and believers remain subject to their original church, unless by agreement with it. This doctrine means that conformity to the will of the community is fundamental, and submissiveness is expected. Weekly communion on the first day and baptism by immersion were expected.

The doctrine of the family was the final cornerstone. Marriage occurs when sexual relations commence, and does not require a marriage license. Divorce is not possible. Wives submit themselves to their husbands. Young people are to be married when they are sexually mature, and parents and church leaders play a key role in identifying spouses. Birth control is wrong. Children may be punished by their parents, and parents are responsible for the schooling of their children. Children of believers still have to believe for themselves. Children should be given godly names.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The influence of the Hutterites and Bruderhof is evident in aspects of the community. Hopeful Christian was deeply concerned that all community members should be equal (Tarawa 2017:14-15). This began with experiments in buying groceries for each other and then in bulk, using a points system (Tarawa 2017:13). So living in Christian community is the central feature of Gloriavale. Their booklet A Life in Common (also available on the web) describes the hostels that they built at Haupiri, with up to eleven families on each floor, with just two rooms for most families except for those with more than twelve members (who were allowed three bedrooms). Meals were eaten in the combined hall, although after 2018, tea was taken on the floor of the residential building with the families on this floor.

Full members signed a Declaration of Commitment, which declared that: “I will never take this Christian community or any person in it or the church at Springbank Trust or any of its board members to any law courts or any other state authority, local body authority or anybody outside this church over any matter but will settle any dispute of any kind with any member of this church only before the leaders and brethren of this church” (Royal Commission 2022:47). A revised commitment (2019) again retained a commitment to “live here for the rest of my life unless the shepherds of this Church ask me to serve Christ elsewhere,” and a declaration:

I believe that the overseeing shepherd and the shepherds of our Christian Church Communities are called and ordained of God and that He holds them in His hand. I willingly submit myself to them in love and faith in every area of my Christian faith and practical life, as they live and teach according to the Word of God, trusting in my heart that God will work out His will overall as I do so. I will neither hold nor teach any doctrine or belief contrary to what they teach. I submit myself likewise in love and faith to all others in authority in this Church and to my brothers and sisters in Christ, esteeming others better than myself.

Signatories agreed to share all money and asserts for Christian partners the Christian Church Community Trust, and agreed that “if ever I wilfully break them, I do so to the peril of my soul” (Gloriavale Christian Community 2019). Making a public commitment was a crucial step for members of the community (Tarawa 2017:167-82). In the case of Lilia Tarawa, her commitment was filmed by television cameras. In 2022 the community was forced to tone down the demands of the commitment.

Baptism was by immersion on profession of faith and admitted people to communion on the first day of the week (Tarawa 2017:72-73). Speaking in tongues was the mark of spirit baptism that might accompany water baptism (Tarawa 2017:74). Children are to be baptised from about age seven and thus become members of the community. At age eighteen people choose to become a partner, and make their commitment to the church and sign the commitment in front of the community (Royal Commission 2022:48). Forsaking of family outside of the community was part of this rule. If someone was put out of the community, then all contact with them ceased. There are strong mechanisms to purify the community, and when forbidden items are found, the community is ordered to repent and forbidden things are surrendered and burnt on threat of hell (Tarawa 2017:136-39).

People were required to live in unity with each other, with extreme pressure on younger people to support the shepherds. Children and women were to be in submission, but the community did not reprove serious cases of abusive physical discipline (Tarawa 2017:106-11). Travel required the approval of the leaders.

By the mid-1980s, members were wearing a uniform copying the Hutterites (Beale 2009:63). [Image at right] Modest dress for females was intended to stop arousing lust in men. Men were not allowed to wear shorts, for the same reason(Tarawa 2017:14-15). Women’s work was generally much more mundane than men’s work, and much more regimented. (Tarawa 2917:19, 57-61).

Gloriavale was active in evangelism, firstly in Cathedral Square in Christchurch in the 1970s and 1980s. One aspect of evangelism was to invite visitors to enjoy the communal life, and it was an attractive feature of the community, with entertainments and special events giving enjoyment to all (Tarawa 2017:140-51). Community members usually were taught to play musical instruments (Tarawa 2017:104-05). Free concerts with choral music have been a feature of the community since it moved to Haupari, with a feast at the end of the concert (Beale 2017:212-13; Hurring 2021:32).

The community is not completely isolated, and the gates of the community cannot easily be shut. They have been featured on television documentaries over many years. They are happy to reach out and welcome visitors, although visitors are supervised. The boundaries are mostly self-regulated. (Hurring 2021:33). The outreach in India seems to have initially been funneled through the Dohnavur Fellowship (a famous charity founded by a British missionary woman, Amy Carmichel in 1902) beginning in 2007, but since 2012 they founded a charitable trust in India. “Faithful Stronghold,” an Indian (formerly Kottapalli Mahesh Babu) who had been part of Gloriavale in New Zealand since 2003 (at the age of twelve), led the Indian community on the land they bought in Tamil Nadu. (See Tarawa 2017:239-40) Features about it were displayed in the most recent TV documentary about Gloriavale.

One very curious feature of Gloriavale is that its extreme fundamentalism is balanced by very contemporary business practices. Although self-sufficiency is the focus, the community did not share the Amish disdain for modern machinery, and consequently trusted members necessarily are active in business dealings (Hurring 2021:32). The community has 2,000 cows in its dairy herd, and they engage in deer farming, guided game hunting, sphagnum moss exporting, meat and offal rendering, air charter and servicing. The home farm of 430 hectares was converted from sheep and beef to dairying. There is a second dairying unit at Glenhopeful nearby, with 500 cows. The business manager has traveled overseas to market their products (Tarawa 2017:17). There also is a helicopter business (Tarawa 2017:17). The helicopter business was used to bring international hunters visit, through Wilderness Quest New Zealand (Tawara 2017:17). The community did not approve borrowing money, but as a result got involved in somewhat shady business practices and were found guilty and ordered to pay reparations of $140,000 in 1993 (Beale 2009:127-28). This case led to more cautious in business practices.

Hurring (2021:77) observed that the community’s isolation has produced distinctive modes of speech and language within the community, especially among women. He noted that “as Gloriavale becomes more distinct in their identity, the females are actively diverging their speech away from the typical NZE dialect” (Hurring 2021:77).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

As the community founder, Hopeful Christian was overall leader and overseeing shepherd. According to the “What we believe” (1989), the overseeing shepherd must be obeyed by everyone he oversees in every aspect of life, and he may make any decision on his own and involve as few or as many people as he chooses in making his decision (Royal Commission 2022:54, quoted in the 1989 commitment).

Alongside Hopeful initially was a group of shepherds who were chosen by the overseeing shepherd, including Howard Temple, and David Courage. Later shepherds included Mark Christian (son of Faithful), Samuel Valor and Enoch Upright (Bayer 2021).

Another group, the Servants (seen as deacons), took responsibility for practical aspects of management. After the death of Hopeful Christian, Howard Temple (previously Smitherman) was appointed chief shepherd and chair of the trust. He resigned in 2019 as chair of the trust, and was replaced by Samuel Valour, who resigned in 2022. Samuel Valour was succeeded Luke Valor.

Education was a key link with the state, as it operated under state guidelines and was required to follow the state curriculum, although it was allowed to have its own emphases. The school was led for many years by Faithful Pilgrim. It became quite large with up to 180 children in attendance, and there was a pre-school with primary and secondary departments. Official reports on the school were issued in 1994. 1997, 2004 and 2011. The 2004 report was very positive on the three early childhood centres “Garden of children 1, 2 and 3.” However, there were suspicions that when the inspectors were present the curriculum was altered to appeal to them.

Criticisms of the school became more pronounced in later official reports, and Faithful Pilgrim was forced to step down by 2018. Some of the teachers had training, mostly through the Open Polytechnic or the extramural programme of Massey University. There are eight teachers, including some with a Limited Authority to Teach. (Royal Commission 2022:86). There was no specific teaching on the Māori aspect of the curriculum, even though thirteen percent of children were Māori at one time. In recent years the approach has changed somewhat. Rachel Stedfast, who was born in the community, and had a diploma in early childhood education through Massey University, became acting principal in 2019 (Royal Commission, 36-37) and her desire was to comply with official regulations. The school in 2022 created an advisory committee to respond to concerns.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

There has long been negative attention focused on Glorivale; it has been accused of being a “cult.” There are several sources of the group’s controversial status: Gloriavale through much of its history was extremely insular; former members organized in opposition to the community, which resulted in negative media coverage; and the community and its leaders were involved or implicated in a variety of controversial and illegal sexual practices.

Gloriavale’s insularity has been combined with regimented hierarchical organization and an intense sense of loyalty. One indication of the community’s posture has been its defiant attitude toward external criticisms, which have been rejected as lies. Members have regarded their leaders as infallible: “They’re like God on earth. Whatever they say is what God’s saying” (Crawley 2016). Any hints of dissent within the community have been viewed as spiritual rebellion. Expelled members were swiftly evicted after intense meetings with the shepherds, although some were initially placed in a hut at Glen Hopeful with the hope that they would reassess their unacceptable behavior (Tarawa 2017:244-45). The community also generally imposed strict rules restricting contact with former members, which created traumatic results for divided families.

The growth in a group of leavetakers, as a result of individual exit decisions and expulsions, resulted in both organized, committed dissidents and negative media coverage. [Image at right] The accounts of leavetakers have been extensively reported, and two have written books on their experiences. [Image at right] The media has reported on issues in the community, and there have been several television documentaries as well. There have been some high profile tragedies among leavetakers, including the suicide of Hopeful’s son, Michael. The courts initially became involved occasionally, but very cautiously. For example Dawn Christian/Cooper, who had been abducted by Phil Cooper when he left the group, was returned by court order to her mother, Sandy, in Gloriavale in 2000.

From the outset there have rumours about unconventional sexual practices in the community. These practices ranged from unconventional to troubling to criminal. Hopeful Christian was a strange combination of Victorian and permissive (Tarawa 2017:19). It has been suggested that Hopeful had become concerned, even before the community began, at his children’s naivety about sex (Tarawa 2017:20). Hopeful seems to have felt that people should be less sexually inhibited (Beale 2009:48). So he taught that children should be permitted to observe their parents having sex (Tarawa 2017:21). Hopeful took the view that the state played no role in marriage (although they did abide by the law that sex was illegal between those under sixteen years of age) and that the chief shepherd and parents should choose marriage partners (Tarawa 2017:51-55). There was a custom, at least at one period, that new couples were invited to dinner by Hopeful and Gloria and then were asked to  undress while Hopeful lay with the wife and Gloria with the husband, although without any sexual involvement (Beale 2009:47). Marriage ceremonies in the community paused while the couple went to a special room to consummate the marriage and then returned for a celebration. [Image at right] There were also stories of nakedness in the spa pool and couples making love simultaneously in a common room. (Beale 2009:49). Hopeful would apparently sometimes attend the consummation of marriages (Tarawa 2017:54).

undress while Hopeful lay with the wife and Gloria with the husband, although without any sexual involvement (Beale 2009:47). Marriage ceremonies in the community paused while the couple went to a special room to consummate the marriage and then returned for a celebration. [Image at right] There were also stories of nakedness in the spa pool and couples making love simultaneously in a common room. (Beale 2009:49). Hopeful would apparently sometimes attend the consummation of marriages (Tarawa 2017:54).

While these unusual sexual practices can be traced in the community from its inception, considerable time passed before his son, Phil, who was already alienated from his father, went to the police with the allegation that his father had forced him to mutual masturbation (Beale 2009:126-27). This complaint about Hopeful was initiated after he married a girl of seventeen (Tarawa 2017:21). July 20, 1993 there were raids at both community locations and Hopeful Christian was arrested (Beale 2009:127). In the court case Hopeful Christian was found guilty of assaulting a nineteen year-old woman with a wooden penis shaped object (The Press 1996, November 28 ). Those who accused Hopeful Christian in 1994-1995 were cast out of the community (The Press 2002, August 17.

Since the 1990s inquiries there have been reports that other people in the group were sexually active with minors, and that the community concealed some of these activities. Claims of abuse were dealt with by the community on the basis that they should be handled internally and not taken to the police. Initially Hopeful Christian dealt with these incidents by himself. (Royal Commission 2022:58), but later other shepherds were involved. They would generally require the offender to repent. Victims would then be asked to forgive the offender in front of either the leaders or the whole congregation of adults (Royal Commission 2022:57). The offender would be put out of the community, sometimes for only a short time (although on the second offence offenders were permanently excluded from the community).

In 2019, after the death of Hopeful Christian, the community was faced with both internal disruption as a new leader was chosen, and severe criticisms from the outside including a police investigation. The shepherds agreed at this time to report abuse to the police. (Royal Commission 2022:36, 49-50). The concerns expressed by various government departments were extensive. Charities New Zealand, which registers charities including the Gloriavale Trust, expressed concern in 2015. A team of officials began to make regular visits to the community to hear any concerns.

In 2020, the Police launched Operation Minneapolis and found that sixty-one young people were involved in abusive incidents, including inter-generational abuse, and that the whole culture of Gloriavale was sexualised. It was so widespread that a lawyer present at the Royal Commission hearing reported that she had not found anyone unaware of cases of abuse. (Royal Commission 2022:62).

There were also occasions when physical abuse occurred. During his time in leadership Temple knew of physical abuse in the 1990s. Only with the police investigation did some of these cases get addressed as criminal conduct. The greatest concern by authorities was the community’s encouragement of parents using corporal punishment to discipline children (Royal Commission 2022:68-69). However, the school appears to have continued the practice. Police vetting was a requirement for school teachers in New Zealand, but this requirement apparently was not enforced in the community (Royal Commission 2022:19).

About 200 people have left the community “in recent years.” Given such numbers, the leavers have become more organised, and a Gloriavale Leavers Trust was established in 2015, [Image at right] and Liz Gregory from Timaru was employed to lead it. The leavers have heightened public awareness of the abuses in the community, and they have also focused on the consequences of leavetaking. Effectively, leavers carry virtually nothing with them. The community was required to make special provision for those who decided to leave. The major provision was that leavers were made a grant of $1,000-$12,000 (Gregory and Kempf, 2019). The Leavers Trust provided people in need with clothing and other basics. However, no redress package was set up because the community claimed that it could not afford the expense. Leavers took the community to court over these matters in 2022, and the employment court found that those in the community should be regarded as employees, and therefore were entitled to back pay for their years of service to the community. This ruling seems likely to present the community with a serious financial crisis.

In May 2022, an apology was issued by the community to the Greymouth Star. The letter insisted that much had changed since the death of Hopeful Christian, and that procedures had been introduced to protect current community members. Child labour was no longer being used except for household chores, and the community had cooperated with government agencies to ensure that regulations were obeyed. The community noted that all the commercial businesses paid tax, and workers paid tax on their earnings. An “absolute assurance” was given that sex offenders would not work with children. The community claimed to have contact with Gloriavale leavers and had provided them with support (Apology 2022). Temple claimed that the community has reached out, but that claim has been disputed.

The Community was made one of the six churches of interest in the Royal Commission on Abuse against Children and Dependent Adults. In a hearing devoted to Gloriavale in October 2022, the Royal Commission questioned the doctrines of obedience, unity and submission to elders and men. Howard Temple and Rachel Stedfast gave evidence, and defended the community, while acknowledging that change was necessary. The report of the Royal Commission was then to be prepared.

Gloriavale has a lengthy and complex history. In its origin the group might be seen as a historically typical fundamentalist group withdrawing from what it perceives as the evils of the current church. However, Gloriavale is caught up in a rapidly changing, complex world that is challenging the viability of its way of life. Given the community’s commitment to increasingly contested practices, the presence of organized opposition, and the loss of its founding shepherd, the community faces an opaque future.

IMAGES

Image #1: Neville Barclay Cooper (Hopeful Christian) in his later years.

Image #2: The Gloriavale community.

Image #3: Howard Temple.

Image #4: Gloriavale attire.

Image #5: Gloriavale Protesters.

Image #6: Marriage ceremony at Gloriavale.

Image #7: Gloriavale Leavers Trust logo.

REFERENCES

Beale, Fleur. 2009. Sins of the father: the long shadow of a religious cult. Auckland: Random House.

Burmeister, H. 2020. The representation of cults/new religious movements in the media. Journalism. Wellington, Massey University. Master of Journalism thesis.

Carr, B. 1992. No grey areas: a rural fundamentalist Christian perspective. Religious Studies. Christchurch, University of Canterbury. Master of Arts thesis.

Clayton, Mark, 2017. “A wing and a prayer.” Aviation Heritage 48/3:128-30.

Crawley, David. 2016. “I believe the truth is here: musings on the Gloriavale Community. Stimulus, 23/2:40-42.

Gloriavale Christian Community. 2019. Declaration of Commitment to Jesus Christ and his church and community at Gloriavale.

Gloriavale Christian Community. 2014. Foundational Scriptures.

Gloriavale Christian Community. 2014. A Life in Common: the Experience of the Gloriavale Christian Community, Haupiri.

Gloriavale Christian Community. n.d. What we believe (a concise summary).

Gregory, L and G; Kempf, B & R, 2019. “Letter to Charity Services,” November 20, with appended list of Categories of concern.

Hostetler, John A. 1987. “New Zealand’s new Christian Community.” Christian Living, Anabaptist Magazine, October, 2-9.

Hurring, G. 2021. Isolation, identity, and gender: an investigation of vowel variation in the Gloriavale Christian Community. Language and Linguistics. Christchurch, University of Canterbury. Master of Linguistics: 106.

Jones, H. 2020. Children’s rights in exclusive religious communities: do they need protecting? Law. Wellington, Victorian University of Wellington. L.L.B. Honours 59.

Lee, Anne 2011. “Discipline and work reward faith-based community” Dairy Exporter, February, 112-117.

Orange, D. 2020. Public religion in the New Zealand memescape. Religious Studies. Wellington, Victoria University of Wellington. Bachelor of Arts Honours Research Exercise.

Pretorius, S.P. 2023. “Is the Gloriavale Christian Community founded on the early Christian church.” Journal for Christian Scholarship, 141-64.

Richter, Anke, Cult Trip: Inside the world of coercion and control, Auckland, HarperCollins, 2022.

Royal Commission of Enquiry into Abuse against Children and Dependent Adults, Transcript of Interview with Howard Temple and Rachel Stedfast, 13 October 2022. Document Library | Abuse in Care – Royal Commission of Inquiry

Sargisson, L. 2004. “Justice inside utopia? the case of intentional communities in New Zealand.” Contemporary Justice Review 7:321-33.

Tarawa, L. 2017. Daughter of Gloriavale. Sydney & Auckland: Allen & Unwin.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Gloriavale Christian Community, Apology, 27 5th Month 2022. Greymouth Star. 27/5/2022.

“Gloriavale, life and death” (TVNZ, August 2015)

“The Awakening”, TVNZ Sunday programme, 2015.

Gloriavale: a woman’s place (TVNZ, 2016).

Gloriavale (documentary, 2022)

On the Gloriavale commune in India, https://indiahap.wordpress.com/2017/04/02/on-the-gloriavale-commune-in-india/

Is there a Gloriavale commune in southern Tamil Nadu? http://indiafacts.org/is-there-a-gloriavale-commune-in-southern-tamil-nadu/

Indian Student sent back. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india/indian-student-in-nz-being-sent-back/story-u8q70AHPFDX5jeRiluRrGL.html

Jehan Casinder, New Gloriavale rising, https://www.pressreader.com/new-zealand/sunday-star-times/20150503/281668253532801

Sensible Sentencing Trust on Neville Cooper https://offenders.sst.org.nz/offender/30503/

Press Christchurch 14 October 2006 [also story about Indian student].

Gloriavale Christian Community ERO review (22/11/2004)

Newspaper references: Joanne Naish, “Gloriavale: a community of volunteers or slaves? Press, 26/2/2022. Lournes, M and Naish, “What we learned about Gloriavale over the last few weeks. Dominion Post, 1/10/2022 A7.

Gloriavale’s grip, New Zealand Listener, 3/9/2022 p 63.

Alanah Eriksen, “Fleeing Gloriavale. ‘I am not a victim’ Bay of Plenty Times 20/2/2021.

Bayer, Kurt, Gloriavale unveiled: what life is really like inside the controversial sect, New Zealand Herald, 20/5/2021 p A10.

Joanne Naish, “Gloriavale workers: volunteers or slaves? Press, Christchurch, 14/11/2020 pp A8-9.

Gloriavale founder dies: death of Gloriavale’s leader is ‘no tragedy’ Press, Christchurch, 16/5/2018 p 13.

Anna Brankin, Moving on from Gloriavale, Te Karaka (Ngai Tahu Magazine) January 2017.

Jarvis, Sarah, Escaping Gloriavale, Dominion Post, 2/5/2015 C1.

Casinder, Jehan, Gloriavale, the hopeful Christian interview Sunday StarTimes, 3/5/2015 p A10.

Penfold, Paula & Bingham, Eugene, Probe on Gloriavale tragedy misled. Press, Christchurch, 17/11/2017 etc.

Escape from Utopia (23 episodes, TVNZ 2024).

Publication Date:

28 April 2024