OLD COLONY MENNONITES TIMELINE

1525: A group of adult men baptized one another, Zurich; other rebaptisms occurred in the Low Countries. This group was eventually known as Anabaptists (re-baptizers) and Mennonites (after one of the leaders in the Low Countries, Menno Simons).

1560: A schism occurred among followers in the Low Countries (now the Netherlands and Belgium).

1600s: Mennonites in the Low Countries migrated to East Prussia (now Poland); Mennonites began to use German in religious services and in schools. Mennonites continued to speak their language of origin, Low German or Plautdietsch, at home.

1789-1803: Mennonites migrated from East Prussia to Russia (now Ukraine), where they established exclusively Mennonite settlements. The oldest settlement was in Chortitiza or Khortitsa and became known as the Old Colony. Significant divisions among Mennonites in Russia over education and worship music emerged. Mennonites firmly established themselves as agricultural communities.

1870s: Mennonites migrated from Russia to Manitoba in Canada and Kansas and Nebraska in the U.S. In Manitoba, Mennonites settled on two large tracts of land, the East Reserve and the West Reserve. The group from Chortitza or the Old Colony settled primarily in the West Reserve.

1885: The villages in the West Reserve, the settlement that originated in Chortitza, formed a single church under a single bishop. They called their church the Reinlaender Mennoniten Gemeinde, and it became popularly known as the Old Colony. This group has refused to accept federal and provincial ideas of how to divide the settlement into villages.

1920: Leaders in the West Reserve, from the Old Colony or Reinlaender Mennoniten Gemeinde, did not accept Canadian ideas about education. They searched for new homelands. In the

1920s, Old Colony Mennonites migrated to Mexico; in the 1940s, a smaller group migrated to Mexico; in the 1960s, from Canada to Bolivia. Other groups migrated within Latin America.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Old Colony Mennonites trace their origins to the sixteenth century Protestant Reformation in Europe. At that time, major leaders like Martin Luther [Image at right] and Ulrich Zwingli broke with the Catholic Church, emphasizing the importance of the Bible and salvation, respectively. Several groups across Europe sought further reforms.

Those who later took the name Mennonite or Anabaptist draw many of their convictions and behaviors from the Swiss Brethren. A group of men in Zurich, including Felix Manz and Conrad Grebel, decided that the other reformers had not gone far enough. In 1525, they baptized one another upon confession of a new faith, meaning that they were re-baptizers, or Anabaptists. At or around the same time, people were gathering in the Low Countries (what are now Belgium and the Netherlands) and professing similar beliefs and  engaging in similar religious rituals. Menno Simons [Image at right] was a prominent organizer of these groups of people and Mennonites draw their name from him.

engaging in similar religious rituals. Menno Simons [Image at right] was a prominent organizer of these groups of people and Mennonites draw their name from him.

In 1560 in the Low Countries, Anabaptists or Mennonites began to formalize their beliefs through a catechism and rules of church life. The central questions for these early Mennonites were how to live together as a community (Gemeinde), how to mark differences between those who belonged to the group and those who remained outside of it, and how to deal with members who failed to uphold these religious and social norms (Werner 2016:122-23; See also Plett 2003).

The first schism among these Mennonites occurred at that time, between Frisian and Flemish factions, from Frisland, today part of the Netherlands, and Flanders, today part of Belgium. Historians have described the divisions as over questions of Flemish community responsibility vs. Frisian individual responsibility; Flemish community pietism or religious devotion vs. Frisian individual pietism; the quantity and quality of household goods (Flemish) and dress (Frisian) or simply as conservative vs. progressive. While these twenty-first century categories do not do justice to sixteenth century lifestyles, from the twenty-first century vantage point, it is clear that early Anabaptists followed their leaders in continually striving for reform. As historian Hans Werner observes, while technology and fashion are the visible expressions of belief, the central questions are around community behavior and how to deal with a community member who is not behaving appropriately (Werner 2016:123). In other words, when a group begins by saying that none were Christ-like enough, except for their own group, it has ripple effects for the next five centuries.

Mennonites in what is now Switzerland and South Germany as well as Mennonites in the Low Countries faced significant persecution for their beliefs, particularly in refusing infant baptism and refusing compulsory military service. The solution for both groups was migration. Many of the Swiss Brethren immigrated to what is now the United States in the 1683, at the invitation of William Penn, who invited many non-majority religious communities (like Quakers) to what is now Pennsylvania. Today, their most visibly distinct descendants became what we know as Old Order Amish and Old Order Mennonites (Kraybill, Johnson-Wiener and Nolt 2013). They, like many other immigrants from German-speaking parts of Europe became part of broader Pennsylvania Dutch or German culture; today Old Order people still speak Pennsylvania Dutch. Some members of these groups immigrated to what is now Canada after the U.S.’ War of Independence from Great Britain, in 1786.

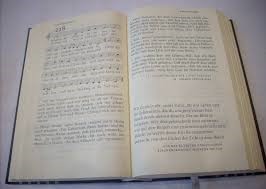

The Mennonites from the Low Countries, including those who are today known as the Old Colony Mennonites, also experienced significant migrations. While some Mennonites remained in the Netherlands (and continue to gather as religious communities today), in the late seventeenth century, a larger group migrated to East Prussia, now Poland. Between migration and 1789, the most important development for Old Colony Mennonites is that Mennonites adopted German as their religious language. They began using a German hymnbook called the Gesangbuch and Luther’s translation of the German bible. [Image at right] Their catechism, which governed community life, was written in German (Neff and Bender 1953.3). It becomes the language of church services, baptisms, weddings, and funerals. Another important element of this century (as it pertains to Old Colony Mennonites) is that the Mennonite communities in Prussia continued to speak Low German or Plautdietsch at home. This was not unlike other Protestant religious communities in the Prussian empire – who may have used Luther’s Bible and its standardized German for written communication, especially across regions, and who maintained their own language at home.

In 1789, Mennonites migrated again, this time to the Russian empire, near what is today Ukraine. Some Mennonite communities remained in East Prussia and Poland until the middle of the twentieth century, largely emigrating after World War Two. The most important development for Old Colony Mennonites is that community life became structured into separate agricultural settlements called colonies, where Mennonite men were exempted from mandatory military service, and where Mennonite children were educated in German by Mennonite teachers. These colonies, so named because of the Russian empire’s desire to promote group settlements, had their own civil and religious leaders who negotiated with imperial authorities on behalf of the entire colony. The first group of primarily Flemish Mennonites migrated to Russia to found the Chortitza or Khortitsa colony in 1789, and a second migration of primarily Flemish Mennonites migrated to Russia to found the Molotschna colony in 1803. As the communities were predominantly agricultural, land was an ongoing issue, and the Chortitza colony founded the Bergthal colony in 1835. Both colonies founded multiple other settlements.

Over the next century, several important changes within and outside the Mennonite colonies occurred, all of which have continued to affect the people we call Old Colony Mennonites. There were significant internal conflicts over education and over how to sing in church and therefore how to teach singing in school (see the section on religious rituals). The outside influence came in the form of pietism, a religious belief that emphasizes personal conversion, that is, a moment where one makes a cognitive assent to a new series of beliefs. This led to the emergence of the Mennonite Brethren church in Russia, which adopted immersion baptism and choral singing.

These conflicts around how to live together as a community in relation to the broader world were solved for some, by accepting Russian in schools, and for others, by migration. Mennonite leaders explored options in the new states of Kansas and Nebraska in the United States and the new province of Manitoba, in Canada. 11,000 people immigrated to the USA. They were more progressive, largely from the Molotschna colony, and were willing to adopt some but not all of the changes imposed by the outside government. They no longer lived in large tracts of land only inhabited by members of the same religious tradition, with their leaders. Indeed, they lived in towns with Mennonites who immigrated from Pennsylvania, as well as migrants from the Eastern U.S. and immigrants from other countries.

A portion of the 8,000 Mennonites who immigrated from Russia to Manitoba would become the Old Colony Mennonites. They were from the Chortitza colony and its “daughter” colonies, and so were already predisposed to preserving community boundaries, especially around education. They settled in two block settlements, which they called the East Reserve and the West Reserve. Both settlements were made up of villages entirely composed of Mennonites, and a Bishop was the sole leader of each Reserve. The East Reserve organized under a bishop in 1873, and the West Reserve, in 1875. Those in the West Reserve called their church the Reinlaender Mennoniten Gemeinde (Zacharias 2011:45-48). They were also most intent on preserving their community boundaries through education and singing in church. Moreover, the settlers in the West Reserve ignored the Manitoba government’s municipal divisions and lived under the authority of the Bishop. In 1880, the two groups officially separated. The Reinlaender Mennonite Gemeinde members on the West Reserve were popularly called Old Colony, because they had come from the oldest Mennonite settlement in Russia.

The Old Colony were the most conservative of the Mennonites in Manitoba, meaning that they were the most determined to follow a separate and more communal way of life: they wanted to live in street villages on a block of land by themselves and run their own affairs; they were firm in resisting all governmental overtures about teaching English in their schools; and they had strict dress codes and rules about the use of technology. (See section on education) Today most Old Colony Mennonites live in Latin America and most white Mennonites with roots in the Dutch-Prussian-Russian migration who live in countries like Mexico, Bolivia, and Belize, belong to Old Colony Mennonite churches.

There are differences even among the churches that carry this name. The biggest distinction has been between those who use electricity at home and in their businesses, and who rely on their own personal vehicles with rubber tires (that is, cars and trucks as opposed to horse and buggy) for transportation. Other distinctions can be made around issues of education, but those would be between Old Colony Mennonites who use electricity and those who do not. Music also continues to be a dividing line, where the Old Colony Mennonites who use horse and buggy for transportation usually singing slower melodies and those who use electricity, singing faster melodies. These groups, however, use the same hymnbook for their songs, the same translation of the Bible, and the same catechism to outline their beliefs and rules for community life.

There are some variations among white, Low German speaking Mennonites who historically held church services in German (today may hold services in Low German). Some of this is because of migration, and some of it is because of evangelization. The migration timeline (divided by country) will expand on this in detail.

In Paraguay, for instance, there are some Old Colony Mennonites (see below). Large numbers of Mennonites immigrated from the Molotschna colony in Russia and then from the Soviet Union to Paraguay in the 1920s and 1940s. They established Mennonite and Mennonite Brethren Churches. A small group immigrated from the West Reserve of Manitoba (who had originally come from the Bergthal colony in Russia) and were conservative but not Old Colony Mennonites in the 1920s. These Mennonites live in their own settlements with their own secular leaders, colony businesses, religious leaders, and schools. People in these colonies all speak Low German and hold church services in German, and today are part of religious denominations that have German, Spanish and Guaraní-speaking members.

A small number immigrated from the Soviet Union to Mexico at the same time, establishing Mennonite Churches there. Then in 1948, a small group of Kleine Gemeinde (conservative but not Old Colony Mennonites) immigrated from Canada to Mexico. Old Colony Mennonites joined these denominations.

From evangelization: Old Colony Mennonites have joined some of the more progressive German-speaking Mennonite denominations in countries where they exist (Paraguay and Mexico), or Low German speaking evangelical denominations. In recent decades, more progressive Amish, and Old Order related groups (Nationwide Fellowship, Beachy Amish, etc) have evangelized Old Colony Mennonites. Some Mennonite-related denominations in Germany have also set up churches and schools among Old Colony Mennonite settlements (Journal of Mennonite Studies 2004; 2013, 2022).

The migration timeline generally indicates that those who migrate or remain in Northern areas (such as Northern Mexican states of Chihuahua and Durango, as well as the United States and Canada) are less traditional Old Colony Mennonites or have left that religious group. Those who migrate South are those who are the most committed to maintaining a traditional lifestyle.

1920: After World War I (1914-1918), Canadian provincial governments passed laws making attendance at English language public schools compulsory. Since most Old Colonists would not send their children to such schools, they had to pay fines. They also sought new homelands. Old Colony and Bergthaler Mennonite leaders from Canada visited Mexico and Paraguay. In Mexico, Old Colony leaders negotiated with representatives from then-president Álvaro Obregón. He assured them of complete freedom in the education of their children, control over their own affairs and exemption from military service and from swearing oaths. One reason why Obregón agreed to their requests is that Mexico was still in the midst of a revolution (having established itself via constitution only in 1917), and so as the leader, Obregón wanted to attract good farmers and loyal subjects in northern Mexico. These areas had become depopulated during the revolution and were places where many people were loyal to other revolutionary leaders (Nugent 1993:112; Janzen 2018:61-82).

In 1922, 6,000 Low German speaking Old Colony Mennonites, along with smaller numbers of Bergthaler Mennonites, from Manitoba and Saskatchewan, migrated to the Mexican states of Chihuahua and Durango.

In 1948, small numbers of Old Colony Mennonites and Kleine Gemeinde migrated to Mexico.

During the 1950s, Old Colony Mennonites who had access to Canadian citizenship began migration to Canada for summer farm labor, and permanent settlement, especially in Southwestern Ontario, Southern Alberta and Southern Manitoba. This was due to decades of drought, farming technologies that had worked in Canada being unable to adapt to Mexico. Large families led to constant pressures to find more land; more people moved back to Canada to escape poverty (Friesen 2004:131-44). Some people wanted schools that provided more than six years of education with a limited, German language, Bible focused, curriculum; and new church groups began to appear.

There has been considerable Old Colony migration within and between nations over the last century:

Over the course of the twentieth century, there was some expansion into neighboring states of Zacatecas and Tamaulipas.

During the 1970s, there was migration to Texas in the United States.

Through the 1990s, internal and external migration took place on a greater scale. After the North American Free Trade Agreement was signed and put into effect in 1994, all but one colony in Northern Mexico adopted electricity. This coincided with a period of massive economic instability in Mexico, the beginning of the so-called War on Drugs. It led to significant out-migration for more conservative (i.e. non-electric, horse-and-buggy) Old Colony people to other colonies in southern Mexico (Campeche), Belize, and Bolivia, leaving deep divisions within colonies and families.

In 2020, Sabinal, the last non-electric colony in Northern Mexico, adopted electricity. This resulted in many colony members migrating to Campeche.

In 1958, Old Colony Mennonites migrated to British Honduras, which is now Belize. There currently are very traditional colonies, as well as less traditional Old Colony settlements, and other types of Mennonites.

In the 1990s, a group of Kleine Gemeinde Mennonites with Old Colony background migrated from Belize to Nova Scotia, Canada.

In the 1960s, large numbers of Old Colony Mennonites migrated to Bolivia from Canada (1967) and Mexico (at various points throughout the decade).

In the 1980s and 1990s, Mennonites in Belize migrated to Bolivia.

During the 1920s and 1940s, Mennonites migrated from Canada and Russia/the Soviet Union to Paraguay. They established colonies but are not Old Colony Mennonites.

In the 1990s, Old Colony Mennonites from Mexico established their first colonies.[[x]]

In the 1980s, Mennonites from Mexico establish colonies in Argentina.

In 2016, Old Colony Mennonites from Mexico established colonies in Colombia.

In 2017, Old Colony Mennonites from Bolivia and Belize migrated to Peru and founded four colonies.

In the 2020s, Mennonites from Bolivia establish colonies in Angola.[[xi]]

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Old Colony Mennonites, like other Mennonite and Anabaptist Christians, believe in community, and adult participation in a community of faith after joining it via baptism. They, like Old Order Mennonites and Amish, take very seriously the idea of maintaining a community that is separate from the surrounding world, with implications for military service and education.

A fundamental aspect of Old Colony Mennonite life is living in a separate community, where children learn the catechism in separate schools so that they can participate in this separate community as adults. Therefore, religious practices, education and beliefs are intertwined.

The beliefs are best represented by the Elbing catechism, which demonstrates multiple similarities with other Christians, in particular, with other Protestants. Old Colony Mennonites profess belief in the Trinity, that God is revealed in the Bible, the idea of heaven after death, a final judgment from a divine power, and ideas about sin and salvation. The catechism also stresses the importance of a community of believers, the necessity of living in this community to perhaps go to heaven after death. Some distinct practices include adult baptism, refusing to say oaths, and refusing military service. These and other non-Christian behaviors can lead the community to ban a member (“Elbing Catechism” 2021).

In practice, Old Colony men elect male ministers for individual congregations, and a male bishop to supervise a group of churches. According to John J. Friesen, un-ordained lay members do not play public roles or have a say in church matters; rather, they participate in the religious life of the community by living by its norms. The norms address many areas of life, including military service, dress, lifestyle, modes of transportation, vocations, sexual relationships, conspicuous consumerism, and interpersonal relationships.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Old Colony worship services involve many elements common in other Christian churches: singing, Bible reading, prayers, and a sermon. These services are held in plain buildings without significant information regarding service times written down anywhere. They begin as early as 8:00 AM. Men and women sit on opposite sides of the church. People bring their German, gothic script hymnbooks (or Gesangbuecher) with them. [Image at right] To sign, the congregation follows the Vorsaenger or song leader and group of male song leaders. The vorsaenger give a hymn number, and then start singing a line, and then the congregation joins in without any instruments to accompany them. The more conservative Old Colony churches will sing a slower melody, called Langewiese, or Aulewiese, that some have compared to Gregorian chanting; other Old Colony churches, meaning those who’ve accepted some of changes, use a melody that is a little less slow. It is called Kurzewiese. According to Hans Werner “The Ole Wies was never meant to be a performance of aesthetically pleasing sound, but rather was an/ emotional coming together of individuals in a communal act of worship” (2016:129-30).. In my experience the Kurzewiese has a similar effect.

Old Colony worship services have two silent prayers for which the people kneel. The minister reads a sermon in German, having written it himself or taken from earlier ministers. The ministers wear particular clothing: black suit pants, shirt and coat, no tie, and boots. The reason for the boots lies in Ephesians 6:15. In English it says “As shoes for your feet put on whatever will make you ready to proclaim the gospel of peace,” In the German version of this verse the word for shoes is boots.

Old Colony people celebrate communion twice a year. The church emphasizes that before people come to communion, they needed to “make things right” with one another (Friesen 2004:136).

Old Colony Mennonites celebrate most Christian holidays, emphasizing Easter, Pentecost and Christmas, which are celebrated with multiple church services, and no school for children. They consider Epiphany and Ascension to be minor holidays, celebrated with a single day of church (Wall 2017).

Children learn the catechism, Bible, and rudimentary writing and arithmetic in order to join the church in adulthood (Crocker 2016). Young adults must be baptized before marriage, and must prove they have memorized the catechism before baptism. Engagements are celebrated two weeks before marriage, and typically in the bride’s home. Weddings take place in church, at the end of a church service.

Funerals are similar to other church services. A trajchtmoake or bone setter will usually be the community midwife and undertaker. She will prepare the body for burial, and lay the deceased person’s body out at home. Sometimes family members may take photographs of the body (even in the groups that shy away from photographs) as it may be difficult or impossible for all family members to attend the funeral.

Each colony has its own restrictions on dress. Old Colony women typically wear mid-calf length dresses with stockings (for women) and socks (for girls). Women also wear black kerchiefs. The way she wears a kerchief, and if it has a print, embroidery or painted design, likely indicates the colony she comes from. Many Old Colony girls only wear head coverings after they are baptized, which usually occurs a short time before marriage. For their daily life, say working in the garden, the women would wear sun hats over kerchiefs. Women and girls are not allowed to cut their hair or wear makeup or jewelry. Some less traditional Old Colony Mennonite girls may cut their hair. All women who wear kerchiefs protect their hair with intricate braids.

More traditional Old Colony Mennonite men wear homemade overalls and shirts, and less traditional ones would wear jeans and button-down shirts. For work they may wear Mexican or Southwestern style cowboy hats, or baseball caps, depending on their colony and country of origin. Young men who have not yet been baptized might have flashy belts. Men are clean shaven with short hair.

Old Colony Mennonites speak Low German or Plautdietsch, which originated in the Low Countries, and, over five centuries of migration, includes vocabulary and linguistic structures from the surrounding cultures. The language is generally not written but it is their primary language for daily conversation. It has some similarities to Pennsylvania Dutch but, as with the Amish and Old Order Mennonites in states like Ohio, Indiana or Pennsylvania. The Bibles, hymnbooks, and catechism of the Old Colony Mennonites are in standard German. Old Colony schools are also primarily in German.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Old Colony Mennonites in Latin America today have a distinct community structure. They live in a similar way as Mennonites in eighteenth and nineteenth century Russia, which nineteenth century Canadian bishops discussed in their sermons. The first Old Colony bishop in Manitoba, Johann Wiebe, [Image at right] preached sermons about community organization (Friesen 2004:132). He established the importance of church leaders as independent from civil authorities. The church bishop should control its “secular” elements, that is, he would vet the colony Vorsteher or secular leader.

Men in Mennonite colonies in Mexico currently can vote for their Vorsteher regardless of church affiliation. A bishop or a group of bishops (depending on colony size) will be appointed to oversee all the churches in a colony. Each village will have a church and a religious school. The church will have its own preacher or minister, a deacon (to oversee social welfare), a song leader and then men who sing with him. The village will also have a teacher who has to be a church member, as the (usually male) teacher instructs children in their hymnbook and catechism to prepare them to be church members. In some colonies a Waisenamt oversees social services such as homes for people with disabilities, homes for elderly people and drug and alcohol rehabilitation centers. In some colonies missionary organizations partner with these programs. Historically the Waisenamt also functioned as a type of credit union, offering loans to community members.

Old Colony Mennonites in Latin America currently live in colonies on the large blocks of land. Each colony is composed of darpa or street villages. A village is essentially a very long street, with houses, barns, a school, and most of the time, a church (if the village is smaller, a couple of villages will share the same church). Crops or orchards are often at some distance from their homes. But in the early decades many became very poor. Crops that had worked well in Canada did not work so well in Mexico; markets were uncertain, it seemed that they had bought land that was not actually the seller’s to sell, and other problems (Janzen 2018:61-82). But in some ways their vision held. Everyone in a given colony belonged to the same church; the church was led by a bishop and a council of ministers; they regulated many aspects of life in the colony. For example, farm tractors with rubber tires were prohibited, and the village schools were carefully controlled.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

There are many issues that face Old Colony Mennonites in Latin America. One is the effects of several generations of migration, between colonies in search of a more appropriate religious future, or back and forth to Canada for summer work, or for those who live close to the U.S. border, working as undocumented people for Old Colony Mennonites in Texas, or other Mennonite communities in Kansas, Nebraska and Oklahoma.

Constant migration creates insecurity, as does the security situation in many parts of Latin America, most notably in North-Central Mexico. Some Mennonites have been kidnapped, with the earliest case documented in Mexico in the 1970s (although this person was not a descendant an Old Colony Church member). Mennonites have been involved in drug-trafficking at lower levels and there have been some high-profile arrests.

Another issue relates to land ownership. In many places, Mennonites (as foreigners) were not able to own their land and so entered land lease agreements with governments. In other instances, once members had gained access to the new country’s citizenship, they purchased land from sellers who may have been misrepresenting themselves as landowners, or land that was under dispute in a land redistribution program. In several cases in Mexico, Indigenous people refused to leave land that was theirs until armed forces removed them, in the 1920s, the 1960s and the 1970s (Janzen 2018:75-82).

Other issues relate to agriculture. As an overwhelmingly agricultural and rural community, Old Colony Mennonites need to purchase more land for their large families, and this land may not be suitable to the type of farming to which they are accustomed (Nobbs-Thiessen 2020). They may also, as in several cases in Northern Mexico, be reputedly drilling too many wells that are far too deep, for agricultural purposes, and thus endangering the future of the region. In Southern Mexico, and perhaps in other places, they are engaged in significant deforestation. Not only is this environmentally devastating, it also destroys the sacred places of their Maya neighbors (Akerson, Kehler and Reynar 2004; Beilin and Weinstein 2022).

There are also issues that arise because most Mennonites cannot communicate with their neighbors. This affects women particularly, as they do not have business contacts and thus less practice with colloquial Spanish, and is particularly challenging when they are having children and using, for example, publicly available health care. This also happens in encounters with the police as there are only a limited number of Low German-Spanish interpreters.

There are very high-profile cases of violence in women’s lives, most notably in Bolivia, which Miriam Toews and Sarah Polley represented in a novel and a film, Women Talking (Toews 2018; Polley 2022). These events pose a challenge to all Mennonite colonies in Bolivia (Kinch 2023; Friedman-Rudovsky 2013; Janzen 2016; Pressly 2019).

The history of Old Colony Mennonites and their current operation suggest that they will continue despite ongoing challenges.

IMAGES

Image #1: Martin Luther.

Image #2: Menno Simons.

Image #3: Gothic script hymnbooks (Gesangbuecher).

Image #4; Johann Wiebe and is wife.

REFERENCES

Akerson, Lars, Tina Fehr Kehler and Anika Reynar. 2024. “The Meaning of Seeds: Groups Seek Mutual Wellbeing amid Maya-Mennonite Tensions.” Canadian Mennonite 28.4, February. Accessed from https://canadianmennonite.org/stories/meaning-seeds on 2 March 2024.

Beilin, Katarzyna and Avi Paul Weinstein, directors. 2022. Maya Land: Listening to the Bees, FelixMundo Production, 1 hr., 8 min.

Cañas Bottos, Lorenzo. 2008. Old Colony Mennonites in Argentina and Bolivia: Nation Making, Religious Conflict and Imagination of the Future. Leiden: Brill.

Crocker, Wendy. 2016. “Schooling across Contexts: The Educational Realities of Old Colony Mennonite Students.” Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies 4.2:168-82.

“Elbing Catechism.” 2021. Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, 1778. Accessed from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Elbing_Catechism&oldid=172028 on 2 April 2024.

Friedman-Rudovsky, Jean. 2013. “The Ghost Rapes of Bolivia.” Vice, December 22x. Accessed from https://www.vice.com/en/article/4w7gqj/the-ghost-rapes-of-bolivia-000300-v20n8 on 25 March 2024.

Friesen, John J. 2004. “Old Colony Theology, Ecclesiology, and Experience of Church in Manitoba.” Journal of Mennonite Studies 22:131-44.

Hamm, Blake. 2023. “Low German Mennonite Migration: A Geopolitical Framework and History.” Journal of Mennonite Studies 41.2:111-146. Accessed from https://www.plettfoundation.org/files/preservings/Preservings22.pdf on 2 March 2024.

Janzen, Rebecca. 2018. Liminal Sovereignty: Mennonites and Mormons in Mexican Culture Albany: SUNY Press.

Janzen, Rebecca. 2016. “Media Portrayals of Low German Mennonite “Ghost Rapes” Challenge the Bolivian Plurinational State.” A Contracorriente 13.3:246-262. Accessed from https://acontracorriente.chass.ncsu.edu/index.php/acontracorriente/article/view/1401/2700 on 2 March 2024.

Journal of Mennonite Studies 22 (2004), 31 (2013) and 41 (2022).

Kinch, Eileen. 2023. “Keepers of the Old Ways: Colony Mennonites in Bolivia Preserve Tradition, Innovate as Numbers Grow.” Anabaptist World, October 27. Accessed from https://anabaptistworld.org/keepers-of-the-old-ways/ on 2 April 2024.

Kraybill, Karen M. Johnson-Wiener and Steven M. Nolt. 2013. The Amish. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Neff, Christian and Harold S. Bender. 1953. “Catechism.” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Accessed from https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Catechism&oldid=174931 on 2 April 2024.

Nobbs-Thiessen, Ben. 2020. Landscape of Migration: Mobility and Environmental Change on Bolivia’s Tropical Frontier since 1952.Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Nugent, Daniel. 1993. Spent Cartridges of Revolution: An Anthropological History of Namiquipa, Chihuahua. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Plett, Delbert, ed. 2003. Preservings 22. Accessed from https://www.plettfoundation.org/files/preservings/Preservings22.pdf. on 25 March 2024.

Polley, Sarah, director. 2022. Women Talking Orion Pictures, Plan B Entertainment and Hear/Say Productions, 1 hr. 44 min.

Pressly, Linda. 2019. “The rapes haunting a community that shuns 21st Century.” BBC News, 16 May. Accessed from https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-48265703 on 25 March 2024.

Toews, Miriam. 2018. Women Talking. Toronto: Knopf.

Wall, Anna. 2017. “Dead Butterflies in Mexico,” Mennopolitan, June 29. Accessed from http://www.mennopolitan.com/2017/06/dead-butterflies-in-mexico.html on 2 April 2024.

Werner, Hans. 2016. “Not of This World: The Emergence of the Old Colony Mennonites,” Journal of Amish and Plain Anabaptist Studies 4.2:121-32. Accessed from https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/amishstudies/vol4/iss2/2/ on 2 March 2024.

Zacharias Peter D. 2011. “Biography of Johann Wiebe, (1837-1905), Rosengart.” Pp. 45-48 in Old Colony Mennonites in Canada 1875-2000, edited by Delbert Plett. Winnipeg, MB: D.F. Plett Historical Research Foundation, Inc.

Publication Date:

26 April 2024