Zbigniew Makowski

ZBIGNIEW MAKOWSKI TIMELINE

1930 (January 31): Zbigniew Makowski was born in Warsaw, Poland.

1950: Makowski was admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw.

1956: Makowski obtained his diploma after working in the workshop of K. Tomorowicz in Warsaw.

1957: The first individual exhibition of the artist took place in the student club Hybrids in Warsaw.

1958/1959: Makowski created his first illuminated book, which opened a series of over two hundred works of this kind. In order to produce it, he worked on a book by Theosophist Annie Besant, writing and painting on a copy of it.

1962: Makowski travelled to Paris, where he met André Breton and became involved with the artistic movement Phases.

1965/1966: Makowski worked as a lecturer in the National Higher School of Fine Arts (from 1996 called University of Fine Arts) in Poznań, Poland.

1973: Makowski received the prestigious Polish Art Critique’s Prize.

1982–1988: Makowski took a break from artistic exhibitions.

1991: The artist’s painting Mirabilitas secundum diversos modos exire potest a rebus (painted between 1973–1980) was presented by the Polish Government to the Office of the United Nations in Geneva.

1992: Makowski received the prestigious Polish Jan Cybis Award for lifetime achievement.

1995: The so called “Blue Exhibition” of the painter, organized for the fiftieth anniversary of the United Nations, took place in the Zachęta Gallery in Warsaw.

2010: Makowski received the Special Prize of the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage.

2010-2019: Makowski continued to live and work in Warsaw

2019 (August 19): Zbigniew Makowski died.

BIOGRAPHY

Zbigniew Makowski is one of the most important Polish contemporary artists. His art includes both paintings and illuminated books. Art critics called his work “metaphorical painting” or “romantic geometry,” because of the forms he uses in his paintings, consisting of geometric figures and fantastic backgrounds with surrealistic elements, which create mysterious, dreamy visions. Makowski’s works are also often called treatises rather than paintings, because the author fills them with words or lines of small letters in many different shapes, reminiscent of graphics in alchemical treatises. His art includes continuous references to the whole tradition of Western esotericism. There is a certain emphasis on Theosophy, but Makowski is influenced by a large multiplicity of esoteric sources.

Zbigniew Makowski was born in 1930 in Warsaw, Poland. From 1950 to 1956, he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. He obtained a diploma by studying in the workshop of Kazimierz Tomorowicz (1897–1961), a landscape painter and a representative of Polish Formism, an avant-garde artistic current emphasizing form over content. Makowski debuted as an artist in the mid-1950s. The political situation in Poland after World War II and the emerging communist regime had an impact on the development of his art. Makowski did not follow the trends officially imposed by the regime, and from the very beginning of his career started looking for non-conventional forms of expression.

to 1956, he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. He obtained a diploma by studying in the workshop of Kazimierz Tomorowicz (1897–1961), a landscape painter and a representative of Polish Formism, an avant-garde artistic current emphasizing form over content. Makowski debuted as an artist in the mid-1950s. The political situation in Poland after World War II and the emerging communist regime had an impact on the development of his art. Makowski did not follow the trends officially imposed by the regime, and from the very beginning of his career started looking for non-conventional forms of expression.

He became a member of an international movement known as Phases, which was born in the early 1950s in France. Phases was established by the French poet and critic Édouard Jaguer (1924–2006), not as a group but as an informal collaborative enterprise of artists engaged in different projects. Phases never published a manifesto, but the common denominator of his artists was the importance it attributed to imagination (Dąbkowska-Zydroń 1994:9–15, 118–20). Makowski was involved with this movement from 1962 on. He first encountered Phases during a trip to Paris, and later he repeatedly exhibited his works together with other artists involved with the movement. In Paris, Makowski also met the father of Surrealism, André Breton (1896–1966), whose artistic explorations became an important source of inspiration for him (Szafkowska 2015:11-16).

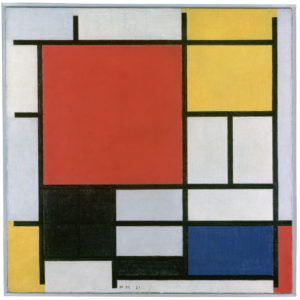

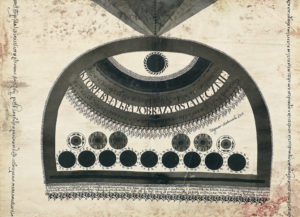

In the initial period of his artistic work (1965–1960), Makowski was strongly influenced by expressionism and existentialism. At that time, he was mostly creating realistic works: still lives, landscapes, and portraits. However, he quickly started to move towards Surrealism and Informalism. In the early 1960s, his art could be characterized as structural abstraction, with the use of simple, and often geometric, shapes in shades of black, white, and grey. In the first half of the 1960s his works were filled with lines (horizontal, vertical, sometimes circular  or parabolic), painted across signs and symbols, letters, or whole sentences (Sowińska 1980:2–5). [Image at right] At this time, the artist was mostly known for his calligraphic compositions, which he himself called “letters written to unknown addressees” (Makowski 1965:8).

or parabolic), painted across signs and symbols, letters, or whole sentences (Sowińska 1980:2–5). [Image at right] At this time, the artist was mostly known for his calligraphic compositions, which he himself called “letters written to unknown addressees” (Makowski 1965:8).

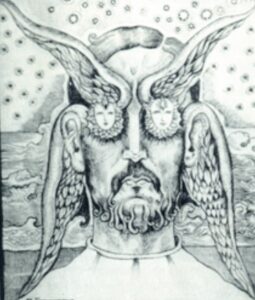

In the mid-1960s, signs and symbols, becoming over time more and more numerous and varied, were placed in landscape backgrounds divided into the two spheres of earth and air. In this scenery, Makowski placed his favorite keys, ladders, stairs, geometrical forms, letters, ciphers, citations, and labyrinths. These elements were realistically painted but did not serve a descriptive function, Rather, they became symbols with a secret meanings, within the framework of a specific artistic and esoteric language that Makowski used but did not explain to his audiences. It is this language that critics nicknamed “romantic geometry.” In the second part of the 1960s and at the beginning of the 1970s, the painter abandoned this style, but came back to it in the 1980s (Sowińska 1980:2–5).

Makowski was awarded many prestigious Polish prizes, among others the Cyprian Kamil Norwid Prize of Art Critique in 1973, the Jan Cybis Award in 1992, and the Special Prize of the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage in 2010 (Szafkowska 2015:11–16). One of Makowski’s paintings, Mirabilitas secundum diversos modos exire potest a rebus, (painted between 1973 and 1980) was presented as a gift from the Polish Government to the Office of the United Nations in Geneva. Works of Makowski are present in the most important museums in Poland, with a large collection is in the National Museum in Wroclaw, and around the world, including in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Throughout his long career, the artist took part in over two hundred collective exhibitions and around one hundred personal ones (Szafkowska 2015:11–16).

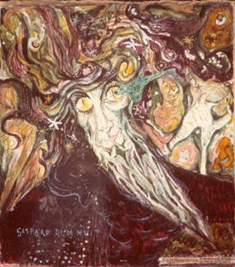

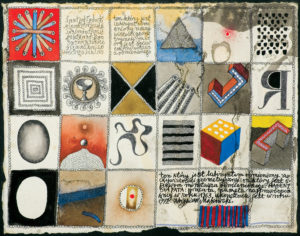

Makowski is an erudite painter, inspired not only by the history of art, but also by literature, philosophy, and the traditions of cultures and religions around the world. Using those inspirations, he created an original mythology based on his own experiences, feelings, and thoughts. He tried to affect not only the aesthetic sense of his audience, but also their emotions, their mind, and their subconscious, converting his works of art into multidimensional spiritual experiences (Nastulanka 1978:6). The surfaces of his paintings are reminiscent of multicolored carpets or richly ornated collages, with a baroque sense of horror vacui (Szafkowska 2015:11–16).

Makowski is also known for creating artistic works that can be called “illuminated books” in the tradition of William Blake (1757-1827). Makowski created over two hundred works of this kind (Szafkowska 2015:11), experimenting with the very form and function of books. The illuminated books are a key to understanding his paintings, and often serve as the basis for future compositions. The books themselves are recreated many times: the artist includes paintings and drawings in them with pencil, ink, gouache, or watercolor, cuts or stitches them, adds his notes, citations, and poetry. They become a kind of magical grimoires, written with an encrypted language, whose multiplicity of meaning cannot be easily discovered by the uninitiated (Bartnik 2008:7–16). The basis for the first “illuminated book” was one of the works of Annie Besant (1847–1933), the second president of the Theosophical Society. The painter started from a printed book and wrote and painted on it. However, Makowski sometimes created his own books from the beginning, using handmade paper and illustrating every single page (Szafkowska 2015:15).

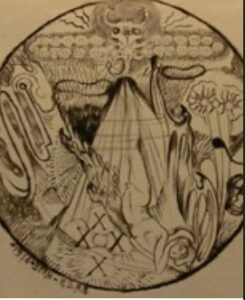

Makowski combines writing and drawing, multiplying the meanings of  his works and making them somewhat hermetic and hard toread. The presence of writing constitutes the original character of Makowski’s paintings. [Image at right] The artist often uses not only his own notes, but also sentences in various languages, among others ancient Greek and Latin, citations from classics of literature, poetry, and so on. There is a characteristic motif of a spiral inscription that appears in several of his works and resembles a mandala. Sometimes, Makowski encrypts his notes; some of them can be read only in a mirror, others are deliberately partly erased (Bartnik 2008:8). One of the inspirations for this “Lettrism” were the works of Abraham ben Samuel Abulafia (1240–91), one of the leading Kabbalists of the Middle Ages, as well as those of an Italian priest, mystic and cartographer of the fourteenth century, Opicinus de Canistris (1296–c.1353), also known as the Anonymous Ticinensis, the creator of the so called anthropomorphic maps (Baranowa 2011:72–79).

his works and making them somewhat hermetic and hard toread. The presence of writing constitutes the original character of Makowski’s paintings. [Image at right] The artist often uses not only his own notes, but also sentences in various languages, among others ancient Greek and Latin, citations from classics of literature, poetry, and so on. There is a characteristic motif of a spiral inscription that appears in several of his works and resembles a mandala. Sometimes, Makowski encrypts his notes; some of them can be read only in a mirror, others are deliberately partly erased (Bartnik 2008:8). One of the inspirations for this “Lettrism” were the works of Abraham ben Samuel Abulafia (1240–91), one of the leading Kabbalists of the Middle Ages, as well as those of an Italian priest, mystic and cartographer of the fourteenth century, Opicinus de Canistris (1296–c.1353), also known as the Anonymous Ticinensis, the creator of the so called anthropomorphic maps (Baranowa 2011:72–79).

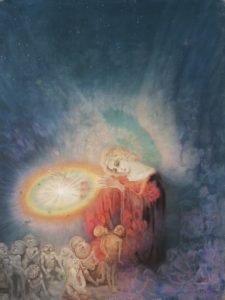

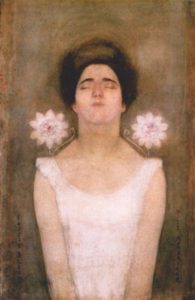

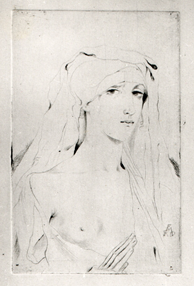

Beyond these references, however, we find in Makowski’s work a great variety of symbols, coming from both Western and Eastern esoteric traditions. [Image at right] His favorite motifs are keys, black birds,labyrinths, stairs, ladders, bevels, gates and portals, spirals, cups, swords, Platonic solids, Tarot cards placed on an oneiric  background. [Image at right] A motif he often uses is a female portrait (a contemporary woman but also a goddess, a Renaissance lady, or a medieval Madonna), appearing where we would not expect it. Nothing is what it seems at first sight to be. Ostensibly realistic elements become archetypical forms, creating “mystical rebuses” (Szafkowska 2015:11–16).

background. [Image at right] A motif he often uses is a female portrait (a contemporary woman but also a goddess, a Renaissance lady, or a medieval Madonna), appearing where we would not expect it. Nothing is what it seems at first sight to be. Ostensibly realistic elements become archetypical forms, creating “mystical rebuses” (Szafkowska 2015:11–16).

Multiple Western esoteric traditions are present in many of Makowski’s paintings and illuminated books. The esoteric reference is not only apparent in the works themselves, but is also explicitly mentioned in the painter’s notes and memoirs. For instance, Makowski mentions his return to Warsaw in 1945, a city in ruin right after the war. He was fifteen, and along with his colored reproductions of paintings by Joseph M.W. Turner (1775–1851) and the Pre-Raphaelites, and his own drawings, he brought with him books by Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925), the founder of Anthroposophy, and by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831–1891), the co-founder of the Theosophical Society. In his Autobiography, Makowski mentions his interest in the Austrian esoteric novelist, Gustav Meyrink (1868–1932), and in Polish messianic philosophers. He took a special interest in the ideas of one of the latter, Józef Maria Hoene-Wroński (1776–1853), although he was not fully convinced by them. He also read the Polish Hegelian philosopher, August Cieszkowski (1814–1894), and delighted in the works of one of the most important Polish Romantic poets, Juliusz Słowacki (1809–1849), himself not foreign to esotericism. Among his acknowledged inspirations, he mentions also Theosophical books such as The Great Initiates, by French Theosophist Édouard Schuré (1841–1929), and The Book of the Living God, by German writer and painter Joseph Anton Schneiderfranken, known as Bô Yin Râ (18761–943) (Makowski 1978:79–90).

Other sources important for Makowski were the classic authors of Western esotericism: Paracelsus (1493–1541), Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499), Éliphas Lévi (1810–1875) (Bartnik 2008:7–11), and William Blake (Szafkowska 2015:11). Like other artists interested in esotericism, Makowski was also influenced by the psychology of Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) (Makowski 2007:66). In addition to Hermeticism, and ancient mysteries, the artist is also a devoted student of Kabbalah, particularly as interpreted by Christian philosophers such as Ramon Llull (ca. 1232–ca. 1315) and Giordano Bruno (1548–1600). Of Bruno, who was burned at stake in Rome in 1600 by the Catholic Church for his unorthodox, esoteric ideas, Makowski wrote: “I owe it to him that I live, and that I have the courage to think” (Makowski 1978:60).

Makowski repeatedly quoted Llull’s treatise Ars Magna (ca. 1305), a part of his philosophical work Ars generalis ultima, and also mentioned the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (1467), an enigmatic fifteenth century Italian esoteric work probably written by Francesco Colonna (c.1433–1527). Ultimately, however, it would be impossible to list all of Makowski’s esoteric inspirations, just as it would be impossible to ascribe him to any specific esoteric movement or current (Janicka 1973:226). Makowski continued to lead his artistic workshop in Warsaw until his death in 2019. His work remains a testimony to the widespread influence of Western esotericism on twentieth and twenty-first century art.

IMAGES**

**All images are clickable links to enlarged representations.

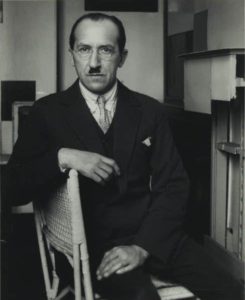

Image #1: Zbigniew Makowski, photo by Mirosław R. Makowski, c. 1974 (in the background: a self-portrait based on a photograph from the artist’s childhood).

Image #2: Zbigniew Makowski, Które były krajobrazy ostateczne [Those that were final landscapes] (1963). Courtesy of Agra-Art Auction House, Warsaw, Poland.

Image #3: Zbigniew Makowski, Labyrinth (1963–1972). Courtesy of Agra-Art Auction House, Warsaw, Poland.

Image #4: Zbigniew Makowski, Mirabilita (1995). Courtesy of Agra-Art Auction House, Warsaw, Poland.

REFERENCES

Baranowa, Anna. 2012. “Zbigniew Makowski.” Pp. 28–34 in Arttak – Sztuki Piekne, no. 3

Baranowa, Anna. 2011.“Ars Magna.” Pp. 73–79 in Dekada Literacka, no. 516.

Bartnik, Krystyna. 2008. Zbigniew Makowski. Wrocław: Muzeum Narodowe we Wrocławiu.

Dąbkowska-Zydroń, Jolanta. 1994. Surrealizm po surrealizmie. Międzynarodowy Ruch „PHASES.” Warszawa: Instytut Kultury.

Hermansdorfer, Mariusz. 1995. “Sztuka Zbigniewa Makowskiego.” Pp. 4–7 in the catalogue Błękitna Wystawa. Warszawa: Galeria Sztuki Współczesnej Zachęta.

Janicka, Krystyna. 1973. Surrealizm. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Filmowe i Artystyczne.

Kuczyńska, Agnieszka and Krzysztof Cichoń. 2008. Wąski Dunaj No 5. Ze Zbigniewem Makowskim rozmawiają Agnieszka Kuczyńska i Krzysztof Cichoń. Łódź: Atlas Sztuki.

Makowski, Zbigniew. 1978. “Autobiografia (fragmenty).” Pp. 79–90 in Zbigniew Makowski (Katalog wystawy). Wrocław: Muzeum Narodowe, and Łódź: Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych.

Makowski, Zbigniew. 1965. “Artysta o sobie.” P. 8 in Współczesność, no. 9.

Makowski, Zbigniew. n.d. “Korespondencja z Jackiem Waltosiem na temat ‘Wesela’ Stanisława Wyspiańskiego.” Pp. 66–68 in Zeszyty naukowo-artystyczne Wydziału Malarstwa Akademii Sztuk Pieknych w Krakowie, no. 8.

Nastulanka, Krystyna. 1978. “Gdzie czekają niespodzianki. Rozmowa ze Zbigniewem Makowskim.” Pp. 8 in Polityka, no. 51.

Sowińska, Teresa. 1980. “Wyobraźnia bez granic.” Pp. 2–5 in Zbigniew Makowski. Zeichnungen, Gouchen und Aquarelle. Berlin: Ośrodek Informacji i Kultury Polskiej Leipzig.

Szafkowska, Magdalena. 2015. “Księgi artystyczne Zbigniewa Makowskiego.” Pp. 11–16 in Polia 10.VI.1946, edited by M. Szafkowska. Wrocław: Muzeum Narodowe we Wrocławiu.

Zbigniew Makowski’s works in NYC Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Accessed from https://www.moma.org/artists/3706?locale=en&page=1&direction = on 20 February 2017.

Post Date:

20 February 2017