GYZIS TIMELINE

1842 (March 1): Nikolaos Gyzis (or, in German, Nikolaus Gysis) was born in the village of Sklavochori, on the island of Tinos, in Greece.

1854: Gyzis started studying at the School of Arts in Athens, where he had among his teachers German Nazarene painter Ludwig Thiersch.

1862: Gyzis was awarded a scholarship from the Evangelistria Foundation of Tinos.

1865: Gyzis finally arrived at Munich, where he settled for the rest of his life. In October, he attended the preparatory class of Hermann Anschütz at the Munich Academy.

1868: Gyzis was accepted in the class of Karl von Piloty at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts.

1869: His first religious painting, Joseph in Prison, was donated by Gyzis to the Evangelistria Foundation of Tinos.

1872: After a long residence abroad, Gyzis visited Greece again for the first time.

1873: Gyzis underwent a trip to Anatolia with fellow artist Nikiforos Lytras.

1874: Gyzis returned to Munich and, together with Lytras, rented the apartment that previously served as the studio of German painter and Theosophist Gabriel von Max.

1875: Gyzis became a member of the Art Association “Allotria,” which several important German artists had also joined.

1880: Gyzis was elected honorary member of the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, and two years later he started working there as a teaching assistant.

1884 (July 27): The German Theosophical Society was founded. It held its second meeting in the same year (August 9) at Gabriel von Max’s Ammerland villa.

1888: Gyzis was appointed professor at the Munich Academy.

1893 (August 28): In a letter to his sister-in-law Ourania Nazou, Gyzis declared that he had conceived a new religious idea.

1894: Gyzis began corresponding with Anna May, a friend and classmate of his daughter Penelope.

1898: With Anna May’s help, Gyzis chose some of his sketches in black and white for the exhibition held in the Glaspalast in Munich in the same year.

1900 (July 20): The Annual Exhibition was inaugurated in the Glaspalast; Behold, the Bridegroom Cometh was among Gyzis’s works exhibited.

1901 (January 4): Gyzis died in Munich. A commemorative exhibition took place in the Glaspalast (from June to October) where Gyzis’s works were exhibited beside those of two other recently deceased painters, Arnold Böcklin and Wilhelm Leibl.

1910 (August 25): Rudolf Steiner delivered a lecture on Gyzis to the members of the Theosophical Society in Munich.

1911 (December): Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) published On the Spiritual in Art.

1928: A large exhibition of Gyzis’s works was organized in Athens.

BIOGRAPHY

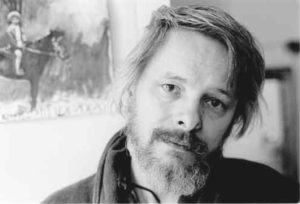

Nikolaos Gyzis (1842-1910) was a prominent Greek painter, much appreciated by his contemporaries for his ability to intertwine in his visual vocabulary elements from the ancient Greek heritage, the Byzantine imagery, and the more recent Jugendstil movement. [Image at right] He spent his entire life in Munich, Germany, initially studying there before becoming a professor at the local Academy of Fine Arts from 1888 until his death in 1901. He is considered the main representative of the so-called Munich School movement, and his work had a great impact on Greek artistic production during the fin de siècle and the beginnings of the twentieth century. Among his students in the Academy were the Austrian printmaker Alfred Kubin (1877-1959), the German graphic artist August Heitmüller (1873-1935), the set designer Ernst Julian Stern (1876-1954), the Romanian painter Ştefan Popescu (1872-1948), and the Polish painter Tadeusz Rychter (1873-1943?), who would eventually become an Anthroposophist. Gyzis’s late work, hovering between academicism and new symbolist tendencies, caused a sensation among his contemporaries, especially in Greece (Katsanaki 2016). After Gyzis’s death in 1901, his late paintings drew the attention of Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), at that time a prominent Theosophist and the future founder of Anthroposophy. He admired the fact that the painter, at the meridian of his artistic life, left behind the traditional genre scenes that were typical for a professor in the Academy and moved to a more spiritual style of painting, including strange angelic beings and apocalyptic imagery (Picht 1951:419-21). [Image at right]

Nikolaos Gyzis (1842-1910) was a prominent Greek painter, much appreciated by his contemporaries for his ability to intertwine in his visual vocabulary elements from the ancient Greek heritage, the Byzantine imagery, and the more recent Jugendstil movement. [Image at right] He spent his entire life in Munich, Germany, initially studying there before becoming a professor at the local Academy of Fine Arts from 1888 until his death in 1901. He is considered the main representative of the so-called Munich School movement, and his work had a great impact on Greek artistic production during the fin de siècle and the beginnings of the twentieth century. Among his students in the Academy were the Austrian printmaker Alfred Kubin (1877-1959), the German graphic artist August Heitmüller (1873-1935), the set designer Ernst Julian Stern (1876-1954), the Romanian painter Ştefan Popescu (1872-1948), and the Polish painter Tadeusz Rychter (1873-1943?), who would eventually become an Anthroposophist. Gyzis’s late work, hovering between academicism and new symbolist tendencies, caused a sensation among his contemporaries, especially in Greece (Katsanaki 2016). After Gyzis’s death in 1901, his late paintings drew the attention of Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), at that time a prominent Theosophist and the future founder of Anthroposophy. He admired the fact that the painter, at the meridian of his artistic life, left behind the traditional genre scenes that were typical for a professor in the Academy and moved to a more spiritual style of painting, including strange angelic beings and apocalyptic imagery (Picht 1951:419-21). [Image at right]

Gyzis was born, on March 1, 1842, to an Orthodox family in the village of Sklavochori, on the island of Tinos, which was also a place with a strong Catholic heritage and a large Catholic population. Tinos, an island belonging to the Northern Cyclades group, is very well known for its famous sculptors and painters, but remains also a very important religious center, notably after the discovery in 1823 of the supposedly miraculous icon of the Virgin Panagia in the ruins of an old church dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, and the subsequent erection of the Church of Panagia Evangelistria in 1880 (Missirli 2002:339). Since the nineteenth century, Tinos has remained a prominent site of Marian pilgrimage and religious tourism, its importance in Greece being comparable to that of Lourdes for Catholics in France.

Gyzis settled in Athens in 1850 and, by 1854, started his studies at the School of Arts. Among his teachers was the German painter of religious subjects, part of the Nazarene movement, Ludwig Thiersch (1825-1909), who is credited with the introduction of Western elements into the Eastern pictorial tradition. According to Kaiser, Thiersch was preoccupied with the Slavic notion of “Sobornost” (roughly translated as “conciliation” or “community”), and the Church of St. Nikodemos in Athens (the local Russian Orthodox Church), which was decorated by him, manifested this preoccupation (Kaiser 2014). The proponents of “Sobornost” were promoting an understanding of the Church as a place of union between different Christian fractions and, on the other hand, were offering an alternative to unbridled individualism by endorsing a kind of universal love and unrestrained solidarity. Thus, hierarchy and institutionalized religion were often seen under a critical lens. Even after Gyzis moved to Munich, he nevertheless maintained a correspondence with Thiersch, exchanging views with him on various artistic subjects (Kaiser 2014:195).

With the aid of his friend Nikiforos Lytras (1832-1904), also a prominent Greek painter who studied in the Munich Academy, Gyzis became acquainted with the wealthy Tinian businessman Nikolaos Nazos (who later became his father-in-law), who intervened in his behalf with the Evangelistria Foundation, securing the grant of a scholarship (Missirli 2002: 341). The Evangelistria Foundation of Tinos endorsed cultural awareness by awarding scholarships to young talented painters and sculptors, thus giving them the opportunity to receive training in important art centers abroad, to deepen their own cultural ideas and import them back into Greece. After some delay, Gyzis’s scholarship was approved in 1865 and from the port of Syros, through Trieste, Vienna and Salzburg, he finally arrived at Munich, where he settled for the rest of his life. In October of the same year, he attended the preparatory class of Hermann Anschütz (1802-1880) at the Munich Academy and, one year later, he was trained by the Hungarian painter Alexander von Wagner (1838-1919). In 1868, Gyzis was accepted in the class of Karl von Piloty (1826-1886) at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts. In 1869, Gyzis bequeathed his first religious painting, Joseph in Prison (1868), to the Evangelistria Foundation (where it still is), as a sign of gratitude for its support. One year later, another religious work, Judith and Holofernes (1869), was completed. The compositional approach as well as the color arrangement of these early works were strongly permeated by the teaching method of von Piloty, one of the most important German representatives of the so-called historical realism (Didaskalou 1999:143).

In 1872, after a long residence abroad, Gyzis visited Greece again for the first time and received high acclaim for his artistic mastery. The following year, Gyzis underwent a trip to Anatolia with Lytras. In 1874, he returned to Munich and, together with Lytras, rented the studio that had belonged to the German painter, and later Theosophist, Gabriel von Max (1840-1915) (Missirli 2002: 346). At the same time, Gyzis began systematically taking part in the annual and international exhibitions at Munich’s Glaspalast.

In 1875, Gyzis became a member of the art association “Allotria,” which many important German artists had also joined (Missirli 2002:347). In 1876, Gyzis got engaged to Nikolaos Nazos’ daughter, Artemis Nazou (1854-1929), whom, in the course of the following year, he married after a cursory trip to Greece. At the same time his reputation as a painter flourished as he began to exhibit his paintings at international venues, such as the Paris World Exhibition of 1878. In 1880, he was elected honorary member of the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, and two years later he started working as a teaching assistant there. In 1888, Gyzis was finally appointed a professor in the Munich Academy, with an annual wage of 4.200 German marks (Didaskalou 1991:150). In 1887, impressed by the international renown the painter had gained in Europe, the Greek government commissioned him to design the banner for the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Gyzis’s career was at its apex when, in 1896, he designed the diploma for the first modern Olympic Games to be held in Athens. According to the painter, the subject depicted in the diploma was the “Annunciation of Greece” [Ευαγγελισμός της Ελλάδος] (Drosinis 1953:210).

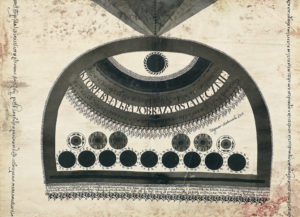

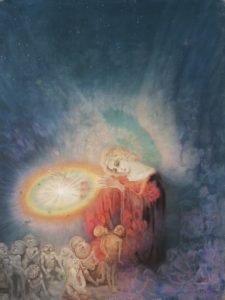

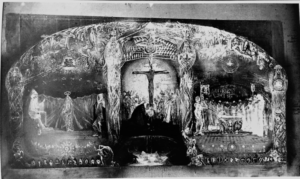

As it might be inferred from his correspondence, by the early 1890s onward, Gyzis underwent a kind of religious crisis and became obsessed with grand religious projects (Didaskalou 1993:188). On August 28, 1893, in a letter to his sister-in-law Ourania Nazou, Gyzis declared that he had conceived a new religious idea. In 1894, he began corresponding with Anna May (1864-1954), a friend and classmate of his daughter Penelope (1879-1947). With May’s help, in 1898, Gyzis chose some of his sketches in black and white for the Munich’s Glaspalast Exhibition of the same year. The sketches were considered as products of musical inspiration, and most of them explored religious themes. On July 20, 1900, the Annual Exhibition in the Glaspalast featured several works by Gyzis, including Behold, the Bridegroom Cometh. This and other religious paintings manifested an obsession with spirituality and the ideas of death and judgement. [Image at right] The murky vibe that these paintings impart to the viewer may be partly due to the devastating defeat that the Greeks suffered in what it is known in Greece as the Unfortunate War, fought in 1897 between the Kingdom of Greece and the Ottoman Empire.

As it might be inferred from his correspondence, by the early 1890s onward, Gyzis underwent a kind of religious crisis and became obsessed with grand religious projects (Didaskalou 1993:188). On August 28, 1893, in a letter to his sister-in-law Ourania Nazou, Gyzis declared that he had conceived a new religious idea. In 1894, he began corresponding with Anna May (1864-1954), a friend and classmate of his daughter Penelope (1879-1947). With May’s help, in 1898, Gyzis chose some of his sketches in black and white for the Munich’s Glaspalast Exhibition of the same year. The sketches were considered as products of musical inspiration, and most of them explored religious themes. On July 20, 1900, the Annual Exhibition in the Glaspalast featured several works by Gyzis, including Behold, the Bridegroom Cometh. This and other religious paintings manifested an obsession with spirituality and the ideas of death and judgement. [Image at right] The murky vibe that these paintings impart to the viewer may be partly due to the devastating defeat that the Greeks suffered in what it is known in Greece as the Unfortunate War, fought in 1897 between the Kingdom of Greece and the Ottoman Empire.

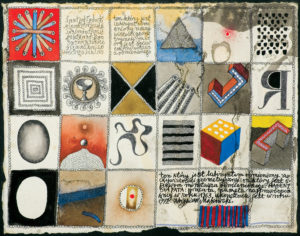

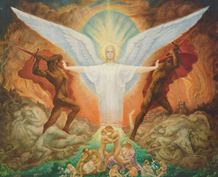

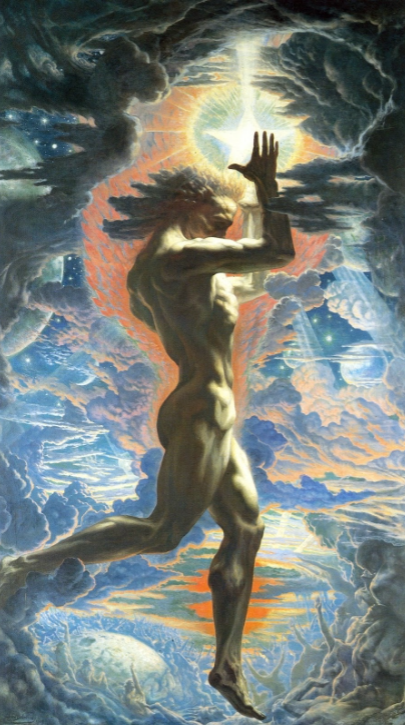

The various sketches, studies, and drawings of this period, now preserved in private collections and museums in Greece, reveal that the painter conceived those fragmented visions from an unseen world, as musical variations on a “greater theme,” i.e. the restoration of spirituality. [Image at right] Gyzis wasn’t satisfied with an ordered synthesis but rather was seeking to circumscribe this “greater theme” by working with different artistic media or knitting unforeseen narratives, gradually unwinding the yarn in front of the viewer’s eyes. The sketches and drawings, which often bear the name Triumph of Religion or Foundation of Faith (since 1894), depict austere archangels in a majestic and statuesque-like posture, holding flaming swords and trampling on the ancient serpent, Satan (Didaskalou 1991:124-25) [Image at right]. For Gyzis, the tireless battle he depicted stood for the eternal fight between Spirit and Matter, a subject often discussed in Theosophical circles (Petritakis 2013). Gyzis emphatically pointed towards this idea in his drawing The Victory of Spirit over Matter, intended as the upper part of a larger composition, entitled The New Century (1899-1900), of which various studies and oil drawings are preserved.

The various sketches, studies, and drawings of this period, now preserved in private collections and museums in Greece, reveal that the painter conceived those fragmented visions from an unseen world, as musical variations on a “greater theme,” i.e. the restoration of spirituality. [Image at right] Gyzis wasn’t satisfied with an ordered synthesis but rather was seeking to circumscribe this “greater theme” by working with different artistic media or knitting unforeseen narratives, gradually unwinding the yarn in front of the viewer’s eyes. The sketches and drawings, which often bear the name Triumph of Religion or Foundation of Faith (since 1894), depict austere archangels in a majestic and statuesque-like posture, holding flaming swords and trampling on the ancient serpent, Satan (Didaskalou 1991:124-25) [Image at right]. For Gyzis, the tireless battle he depicted stood for the eternal fight between Spirit and Matter, a subject often discussed in Theosophical circles (Petritakis 2013). Gyzis emphatically pointed towards this idea in his drawing The Victory of Spirit over Matter, intended as the upper part of a larger composition, entitled The New Century (1899-1900), of which various studies and oil drawings are preserved.

However, Gyzis’s most celebrated painting, in this context, was the already mentioned Behold, the Bridegroom Cometh (1899-1900, 2 x 2 m.), which has as its theme the arrival of the Bridegroom (in Greek, Nymphios), a service of the Orthodox Church that symbolizes the preparation for the arrival of the Messiah. [Image at right] In fact, Gyzis particularly drew on a book called Hermeneia (1730-1734) by Dionysius of Fourna (c. 1670 – after 1744), a manual of iconography, which provided a synthetic Gospel account of the life of Jesus Christ. Gyzis sought after this book in a letter dated 1886 (Kalligas 1981:176-88; Drosinis 1953:176-78). The painting depicts Christ, whose figure emerges throughout various rings of fire, which vehemently coil in vorticose motions up to the margins of the picture, where the angelic hosts genuflect (Petritakis 2014). A scene depicting the Fall of Satan was equally conceived to occupy the lower part of the composition (Kalligas 1981).

However, Gyzis’s most celebrated painting, in this context, was the already mentioned Behold, the Bridegroom Cometh (1899-1900, 2 x 2 m.), which has as its theme the arrival of the Bridegroom (in Greek, Nymphios), a service of the Orthodox Church that symbolizes the preparation for the arrival of the Messiah. [Image at right] In fact, Gyzis particularly drew on a book called Hermeneia (1730-1734) by Dionysius of Fourna (c. 1670 – after 1744), a manual of iconography, which provided a synthetic Gospel account of the life of Jesus Christ. Gyzis sought after this book in a letter dated 1886 (Kalligas 1981:176-88; Drosinis 1953:176-78). The painting depicts Christ, whose figure emerges throughout various rings of fire, which vehemently coil in vorticose motions up to the margins of the picture, where the angelic hosts genuflect (Petritakis 2014). A scene depicting the Fall of Satan was equally conceived to occupy the lower part of the composition (Kalligas 1981).

Gyzis’s religious works demonstrate an accomplished artistic skill and an integrated geometrical expression, especially regarding the use of circular and elliptical forms, which impart an impression of “hidden harmony” (Kalligas 1981:72; Petritakis 2016:89). Marcel Montandon (1875-1940), who published a biography of the painter one year after Gyzis’ death, corroborated the above statement (Montandon 1902:118). Furthermore, the playfully rhythmic, vibrant, but still determined stroke that runs through these works, conveys to the viewer a sense of incompleteness. With his series of drawings made with Indian ink on photographic foil, intended to be seen in front of a light source (a technique invented by Gyzis himself) the painter was hinting at an otherworldly universe, like the one explored by Spiritualist mediums. [Image at right] Similarly, the sketches in black paper with white chalk, that he produced, in 1898, with Anna May’s aid (Drosinis 1953:235), evoke the idea of a juxtaposition between an earthly reality and a spiritual otherness. The latter were bought from the Bavarian Government and are now kept in Staatliche Graphische Sammlung in Munich.

viewer a sense of incompleteness. With his series of drawings made with Indian ink on photographic foil, intended to be seen in front of a light source (a technique invented by Gyzis himself) the painter was hinting at an otherworldly universe, like the one explored by Spiritualist mediums. [Image at right] Similarly, the sketches in black paper with white chalk, that he produced, in 1898, with Anna May’s aid (Drosinis 1953:235), evoke the idea of a juxtaposition between an earthly reality and a spiritual otherness. The latter were bought from the Bavarian Government and are now kept in Staatliche Graphische Sammlung in Munich.

Gyzis died on January 4, 1901 in Munich. His monument was sculpted by the German artist Heinrich Waderé (1865-1950). A monumental, commemorative exhibition took place in Munich’s Glaspalast from June to October 1901. Gyzis’s works were exhibited beside those of two other recently deceased painters, Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901) and Wilhelm Leibl (1844-1900). The Bridegroom as well as sketches from the Triumph of Religion were also on display. Only after twenty-seven years, a major exhibition of Gyzis’s works was organized in Greece, at Iliou Melathron (Heinrich Schliemann’s Mansion) in Athens, organized by the Society of Art Devotees and Gyzis’s son, Telemachus (1884-1964).

An interesting question concerns Gyzis’s relationship with Theosophy, a movement in which several of his friends and associates were deeply interested. Gyzis never joined the German Theosophical Society, nor does it seem likely that he had been aware that Theosophical ideas were circulating in Greece during his lifetime. In fact, the Theosophical Society in Athens was founded much later, in 1928 (Matthiopoulos 2005:249). In 1979, during a conversation with Greek critic and curator Marilena Kassimati in Munich, Ewald Petritschek (1917-1997, Gyzis’s grandson and Penelope Gyzis’s son) stated that, at the twilight of his life, the painter had been acquainted with Theosophical literature (Kassimati 2002:45-46). However, in his correspondence, Gyzis never referred to Theosophical books nor to specific Theosophical ideas. Furthermore, Gyzis’s journals, which were in the possession of his son, Telemachus, were burnt during the aerial bombings in January 7, 1944, near the airport, in Athens (Didaskalou 1991:1). It would be risky, therefore, to jump to the conclusion that Gyzis was an orthodox Theosophist.

A fascination for Spiritualism was shared by many artists and intellectuals at that time, most considerably among them the Munich Secessionists Albert von Keller (1844-1920) and Gabriel von Max (Loers 1995; Danzker 2010). The German Theosophical Society was founded on July 27, 1884. The Society held its second meeting in the same year on August 9, at Gabriel von Max’s Ammerland villa, south of Munich, and von Max became deeply involved in Theosophical and Spiritualist matters. In 1886, however, the German Theosophical Society was dissolved in the aftermath of the controversies where Madame Helena Blavatsky (1831-1891), the Society’s international leader, was accused of having fraudulently produced the letters she claimed she was receiving from the mysterious Masters. Von Keller and von Max, together with the physician Albert von Schrenk-Notzing (1862-1929), formed the Psychologische Gesellschaft (Psychological Society), modeled on the Society for Psychical Research in England. Yet, we cannot demonstrate that Gyzis had direct contacts with the Psychological Society.

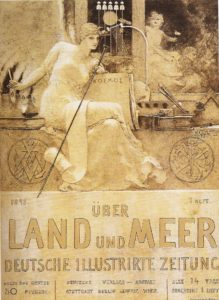

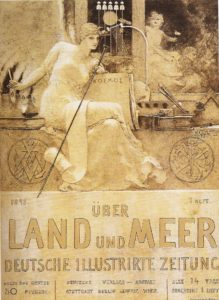

Both Keller and Gyzis were members of the Künstlergesellschaft Allotria (Art Association Allotria), from which later sprang out the Munich Secession. The Art Association Allotria was founded in 1873 by Franz von Lenbach (1836-1904), a very close friend of Gyzis, who also wrote the commemorative introduction to Montandon’s book. What remained hitherto unnoticed, is the fact that Gyzis designed in 1895 the cover for the illustrated magazine Über Land und Meer (Over Land and See), which abounds in Masonic symbols [Image at right]. A member of the editorial staff of the magazine, Ludwig Gärtner, was also a member of the Psychological Society (Petritakis 2013).

In general, Greek art history viewed Gyzis’s work as being engaged in a dialogue with Classical and Byzantine art, the two main threads that allegedly ran through contemporary Greek civilization. As Matthiopoulos correctly indicated, Gyzis’s late work has been viewed and thus appropriated with a certain uneasiness by the intellectual milieu of Greece, and sustained efforts have been made to purge it of its mystical and symbolic elements: in other words, to subdue its “lurid modernization” and supplant it with more representational thought systems and ideologies (Kaklamanos 1901:27-28, Matthiopoulos 2005:541). Kalligas stressed that “Gyzis’s religious works enrich the traditional Christian iconography with a new figure, a figure that cannot be regarded neither as purely Orthodox nor purely Western. It is essentially Christian” (Kalligas 1981:175). Similar tropes of thought have permeated the field of Greek art history until recent times, thwarting the understanding of Gyzis’s late symbolist work in its socio-cultural and ideological context (Danos 2015:11-22). Given the situation prevailing in nineteenth century artistic life in Greece, only a limited circle of artists and literates in Athens and in the Greek diaspora could understand the questions Gyzis’s paintings posed (Matthiopoulos 2016).

Apparently, after the demise of the painter, in 1901, and the concomitant exhibitions of his paintings in Glaspalast, a certain “Theosophical aura” formed around his work. Anna May, a private student of Gyzis, played a certain role in that direction. Her father, Heinrich May (1825-1915), had been Gyzis’s private doctor during the painter’s difficult late years, when Anna played the role of the artist’s muse, whose advice or opinion on various matters he would often solicit.

Margarita Hauschka, Anna May’s niece, reported that in the studio of Anna in Adalbertsstrasse, in the vicinity of the Munich branch of the Theosophical Society, a picture was hanging, supposedly with the title The Majesty of God (Majestät Gottes), apparently, a copy of Gyzis’ Behold, the Bridegroom Cometh, if not the same work. When Tadeusz Rychter, a young painter from Poland, formerly associated with the cultural modernist milieu of the political cabaret Kleiner grüner Ballon [Small Green Balloon] in Krakow. and a student of Gyzis, came to rent the studio and saw the image, he immediately recognized it and asked to keep it in the apartment. Anna May rejected the offer, and Rychter ended up making a small replica of the original work (Hauschka 1975:188). Interestingly enough, a strong erotic relationship blossomed out from this fortuitous event, although it was strongly opposed by Anna May’s parents, since they were strong Catholics and Rychter was a staunch Theosophist. We may thus surmise that it was after having indoctrinated Anna May in Theosophy that Rychter, in the first months of 1910, moved to Berlin to attend some lectures by Rudolf Steiner. It should have been at that time that Rychter drew Steiner’s attention to the Greek painter (Petritakis 2016:84-85). Furthermore, there is evidence that, around 1910, a copy of the Bridegroom decorated the premises of the Munich branch of the Theosophical Society and was well liked by its members (Bracker 2004:61).

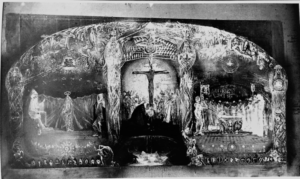

During 1907 and 1910, Anna May, as well as Rychter, worked as set designers for Steiner’s Mystery Plays in Munich, that is, around the time Steiner delivered a lecture on Gyzis to the Munich Theosophical society (Levy 2003). Furthermore, May received a commission from Steiner for a painting that would adorn the Johannesbau in Munich, a forerunner of the Goetheanum Steiner would later build in Dornach, near Basel, Switzerland, as the world headquarters of Anthroposophy (Zander 2007:819). It was conceived as a triptych that should depict the different stages of mystical Christianity, from Solomon as its precursor through the

Holy Grail and up to Rosicrucianism. The work was reminiscent in many ways of Gyzis’s late religious projects, especially in terms of symbolism and compositional arrangement (Petritakis 2014). It is, however, preserved to us only through a transparency kept by May’s niece (Hauschka 1975), since the original painting, once in the Hamburger Waldorfschule, the Anthroposophical high school in Hamburg, was destroyed during the bombings in the Second World War (Hauschka 1975:187). [Image at right] In February 1918, May exhibited the triptych in the Munich gallery Das Reich, run by Anthroposophist and alchemist Alexander von Bernus (1880-1965), and later, the same year, in the Glaspalast, under the last name May-Kerpen (Petritakis 2016:84-85). In 1924, after receiving a commission from the publishing house “Christliche Kunst,” Rychter moved with Anna May, now his wife, to Palestine. In 1939, Rychter’s traces were lost soon after he was commissioned to restore a church near Radom, in Poland. Apparently, he was murdered by the Nazis in 1943 (Levy 2003; Bracker 2004:62). Thereafter, Anna May lived, as a kind of “recluse,” in a small Arabian house, which soon became the first Anthroposophical centre in Palestine, a meeting hub for foreigners and friends (Gottlieb 1954:128-29). Anna May cultivated limited contacts with other Anthroposophists, most of them Jewish expatriates from Central Europe. These included Eva Levy from Vienna (born Eva Rosenberg, 1924-2011), who later, in 1942, got married to the prominent Anthroposophist and pioneer of Zionist movement, Michael Levy (1913-1998), or architect Bruno Eljahu Friedjung, born also in Vienna, in 1906 (Bracker 2004:62).

Before departing with Rychter to Palestine, Anna May was tightly associated with the Künstlergruppe Aenigma, to which both she and Rychter adhered. This group, which exhibited collectively between 1918 and 1932, was founded by Maria Strakosch-Giesler (1877-1970), a former Kandinsky student, and Irma von Duczyńska (1869-1932), both of whom had received an academic art education and were ardent feminists with avant-garde tendencies (Fäth 2015). Gyzis’s work was also very well known to the artists’ group Aenigma, which was mainly steered by Rudolf Steiner and whose members were attendants of his lectures and followers of his ideas.

After Gyzis’s death, Rudolf Steiner, then a leader of the German Theosophical Society, began associating with contemporary art groups and was eager to introduce his ideas on art to young art students who attended his lectures, thereby finding a way to legitimize his activities within the German society. The International Theosophical Congress he organized in Munich in 1907 (May 18-21) was attended by 600 people, most of whom were coming from German-speaking countries, England, France, and America but also from Russia and Scandinavia (Zander 2007:1067-076).

In 1910, Rudolf Steiner presented before the members of the Theosophical Society in Munich the mystery drama by French Theosophist Édouard Schuré (1841-1929), The Children of Lucifer, as well as his own Rosicrucian play The Portal of Initiation (Zander 1998). On August 25, he delivered his lecture on Gyzis. Steiner’s lecture on Gyzis is important, as it was the first time that Steiner thought so highly of a contemporary painter that he dedicated a whole lecture to him. He even ordered a photographic reproduction of the painting to be made in smaller format, which is now preserved in the Steiner Archive in Dornach (Petritakis 2016:84). It seems that Gyzis’s paintings reaped much admiration among the friends of Steiner (who later formed the Anthroposophical community), most of all Behold, the Bridegroom Cometh, to which Steiner predominately dedicated his lecture. Steiner named the painting “Through the light, the love” [Aus dem Lichte, die Liebe]. He was in that way pointing towards an Eastern Christological doctrine, closely related to the idea of Sobornost, which had been widely disseminated in Symbolist circles, most notably in those around Russian philosopher Vyacheslav Ivanov (1866-1949) and composer Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) (Petritakis 2018).

In his lecture, Steiner drew the audience’s attention to the two cosmic spheres that glow in the upper part of Gyzis’s scene, aptly correlating them with the genesis scene by Michelangelo (1475-1564) in the Cappella Sistina in Rome. Furthermore, he argued that the scene echoes the moment at which the new God hovers above to create the world, whereas the old God departs leaving behind demolished shells of the old realm (Steiner 1953). At this time, Steiner’s approach was taking a turn towards more esoteric-Christian ideas. As Max Gümbel-Seiling (1879-1967), a member of the German Theosophical Society and later of the Anthroposophical Society (who had contributed to the preparation of the Mystery Plays in Munich during that Summer) recalled, Steiner imbued the two spheres of the painting with a further cosmological meaning. He argued that, in Blavatskyan terms, the ancient planet on the left of the scene echoes the astronomical period of Manvantara (manifestation) and the new one on the right, the period of Pralaya (retraction) (Gümbel-Seiling 1946:53; Petritakis 2016:87).

Elsewhere in his lecture, Steiner emphasized the use of gold-hued color over the faces and swords of the angels, regarding it as a manifestation of the radiation emanating from the “Spirit of Elohim.” He connected the indigo-blue color with rapt devotion and humility and red with chastity. Since the German Theosophists’ aesthetic predilections were leaning more towards the Madonnas of Raphael (1483-1520), Steiner admonished his audience not to be taken aback by the sketch-like, vaporous coloring of the painting (Steiner 1953:424). This remark is important, since it indicates that Steiner was leaving behind traditional Rosicrucian tropes and engaging in more experimental, one could even say, more avant-garde pursuits. Similarly, in his lectures on art in Dornach, Steiner would elaborate further on the relationship between blue-indigo, which has a centrifugal quality, and yellow-orange, which is centripetal (Petritakis 2014). Artist Maria Strakosch-Giesler recalled how Steiner demonstrated this use of blue-indigo in a series of examples, from Cimabue (ca. 1240-1302) and Giotto (1267-1337) to Filippo Lippi (1406-1469) (Strakosch-Giesler 1955:29; Petritakis 2014).

Perhaps it was precisely Steiner’s encounter with Gyzis’s images that prompted him to conceive or express his new ideas on art theory, rooted mainly in the legacy of German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) (Halfen 2007). Steiner promoted these ideas in the contemporary artistic milieu, in a crucial period of his life when he tried to separate from the occult and aesthetic ideas of international Theosophical leader Annie Besant (1847-1933) and to better adapt to the historical transformations of German society (Petritakis 2013). The reactualization of Goethe’s Farbenlehre (theory of colors) as a “historical necessity” for young artists, firmly indicated by the example of Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), who himself attended Steiner’s lectures and who acknowledged the influence of Theosophy in his seminal theoretical work Concerning the Spiritual in Art, coincided with the revival of esoteric Christianity promoted by the future founder of Anthroposophy (Petritakis 2013, 2016).

IMAGES**

**All images are clickable links to enlarged representations.

Image #1: Nikolaos Gyzis in his studio in the 1890s. Photo by Elias van Bommel.

Image #2: Nikolaos Gyzis, Behold, the Bridegroom Cometh (preparatory sketch, 1899-1900). Oil drawing on canvas, Athens, National Gallery, inv. Π.574/4.

Image #3: Nikolaos Gyzis, Behold the Bridegroom Cometh (preparatory sketch, 1899-1900). Oil drawing on canvas, Athens, National Gallery, inv. Π.574/1.

Image #4: Nikolaos Gyzis, Archangel (study from the The Foundation of Faith), ca. 1894. Oil drawing on canvas, Athens, Benaki Museum, inv. ΓΕ _24317.

Image #5: Nikolaos Gyzis, Behold, the Bridegroom Cometh (1899-1900). Oil on canvas, Athens, National Gallery, inv. Π.641.

Image #6: Nikolaos Gyzis, Fall of Satan (?), 1890-1900. Indian ink on photographic foil, Athens, National Gallery, inv. Π.628/17.

Image #7: Nikolaos Gyzis, frontispiece depicting the Fame, for the periodical Über Land und Meer (1895).

Image #8: Anna May-Rychter, The Triptych of Grail, transparency preserved by Margarita Hauschka (the original is now lost). Rudolf Steiner Archive, Goetheanum, Dornach.

REFERENCES

Bracker, Hans-Jürgen. 2004. “Eine frühe Botin der Anthroposophie in Palästina: Zum 50. Todestag der Malerin Anna Rychter-May.” Pp. 61-63 in Novalis Zeitschrift für europäisches Denken, 58:3.

Danos, Antonis. 2015. “Idealist ‘Grand Visions,’ from Nikolaos Gyzis to Konstantinos Parthenis: The Unacknowledged Symbolist Roots of Greek Modernism.” Pp. 11-22 in The Symbolist Roots of Modern Art, edited by Michelle Facos and Thor J. Mednick. Farnham (Surrey, England) and Burlington (Vermont): Ashgate.

Danzker, Jo-Anne Birnie, and Gian Casper Bott. 2010. Séance: Albert von Keller and the Occult. Washington: University of Washington Press.

Didaskalou, Konstantinos. 1999. Νικόλαος Γύζης (1842-1901). Η συλλογή της οικογένειας του καλλιτέχνη στο Μόναχο [Nikolaos Gyzis (1842-1901): The Collection Belonging to the Artist’s Family in Munich]. Thessaloniki: Reprotime.

Didaskalou, Konstantinos. 1993. Der Münchner Nachlass von Nikolaus Gysis, Two Volumes. Munich: n.p.

Didaskalou, Konstantinos. 1991. Genre– und allegorische Malerei von Nikolaus Gysis. Ph.D. Dissertation. LMU, Munich.

Drosinis, Georgios and Lampros Koromilas. 1953. Επιστολαί του Νικολάου Γύζη [Nikolaos Gyzis’s Correspondence]. Athens: Eklogi Editions.

Fäth, Reinhold, and David Voda. 2015. Aenigma. Hundert Jahre anthroposophische Kunst. Řevnice: Arbor Vitae.

Gottlieb, M. 1954. “Anna von Rychter-May.” Pp. 128-29 in Mitteilungen aus der anthroposophischen Arbeit in Deutschland 29.

Gümbel-Seiling, Max. 1946. Mit Rudolf Steiner in München. Den Haag: De nieuwe Boekerij.

Halfen, Roland, Walter Kugler, and Dino Wendtland. 2007. Rudolf Steiner – das malerische Werk: mit Erläuterungen und einem dokumentarischen Anhang. Dornach: Rudolf-Steiner Verlag.

Hauschka, Margarethe. 1975. “Das Triptychon ‘Gral’ von Anna May.” Pp. 187-90 in Das Goetheanum, Wochenschrift für Anthroposophie, 54:24.

Kaiser, Hanna. 2014. Ludwig Thiersch in Athen um 1850. Neobyzantinismus im Kontext des Philhellenismus. Ph.D. Dissertation, LMU, Munich.

Kaklamanos, Dimitrios. 1901. Νικόλαος Γύζης [Nikolaos Gyzis]. Athens: Estia.

Kalligas, Marinos. 1981. Νικόλας Γύζης, η ζωή και το έργο του [Nikolaos Gyzis: his Life and Work]. Athens: The Educational Foundation of the National Bank of Greece.

Kassimati, Marilena. 2002. “Η καλλιτεχνική προσωπικότητα του Νικολάου Γύζη μέσα από το ημερολόγιο, τις επιστολές του και τις καταγραφές άλλων καλλιτεχνών: μια νέα ανάγνωση της ‘ελληνικότητας’.” [The Artistic Personality of Nikolaos Gyzis as seen through his journal, his letters and the other artists’ testimonies: a new reading of Gyzis’s “Greekness”]. Pp. 37-70 in Νικόλαος Γύζης: Ο Τήνιος εθνικός ζωγράφος [Nikolaos Gyzis: The National Painter of Tinos], conference proceedings edited by Kostas Danousis, Athens: Study Society of Tinos, 2002.

Katsanaki, Maria. 2016. “Nikolaos Gysis (1842-1901) et la réception critique de ses œuvres allégoriques de la dernière décennie du XIX e siècle: Historia, Gloria, Bavaria.” Pp. 47-69 in Quêtes de modernité(s) artistique(s) dans les Balkans au tournant du XX e siècle, edited by Catherine Méneux and Adriana Sotropa, colloquium proceedings, November 8-9, Université Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne, site de l’HiCSA et du centre François-Georges Pariset, Paris 2013. Accessed from http://hicsa.univ-paris1.fr/documents/pdf/PublicationsLigne/Colloque%20Balkans/03_katsanaki.pdf on 30 March 2017.

Levy, Eva. 2003. “Anna May-Rychter.” P. 506 in Anthroposophie im 20. Jahrhundert, edited by Bodo von Plato. Dornach: Verlag am Goetheanum.

Loers, Veit, and Pia Witzmann. 1995. “Münchens Okkultistisches Netzwerk.” Pp. 238-44 in Okkultismus und Avantgarde: von Munch bis Mondrian, 1900-1915, edited by Bernd Apke and Ingrid Ehrhardt. Ostfildern: Edition Tertium.

Matthiopoulos, Eugenios D. 2016. “La réception du symbolisme en Grèce à travers l’œuvre de Costis Parthénis pendant la période 1900-1930.” Pp. 9-46 in Quêtes de modernité(s) artistique(s) dans les Balkans au tournant du XXe siècle, edited by Catherine Méneux and Adriana Sotropa. Proceedings of International Conference, Université Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne, Paris, November 8-9, 2013. Paris: HICSA, Centre François-Georges Pariset. Accessed from http://hicsa.univ-paris1.fr/documents/pdf/PublicationsLigne/Colloque%20Balkans/02_1_matthiopoulos.pdf on 1 April 2017.

Matthiopoulos, Eugenios D. 2008. “Η θεωρία της ‘ Ελληνικότητας ‘ του Μαρίνου Καλλιγά,” [Marinos Kalligas’ Theory of “Greekness”]. Pp. 331-56 in Ιστορικά [Historika] 25:49.

Matthiopoulos, Eugenios D. 2005. Η τέχνη πτεροφυεί εν οδύνη. Η πρόσληψη του νεορομαντισμού στο πεδίο της ιδεολογίας και της θεωρίας της τέχνης και της τεχνοκριτικής στην Ελλάδα [Art Spring Wings in Sorrow: The Reception of Neo-Romanticism in the Realm of Ideology, Art Theory, and Art Criticism in Greece]. Athens: Potamos Publishers.

Missirli, Nelli. 2002. Νικόλαος Γύζης, 1842-1901 [Nikolaos Gyzis]. Athens: Adam (First Edition, Athens: Adam, 1995).

Montandon, Marcel. 1902. Gysis. Bielefeld and Leipzig: Velhagen & Klasing.

Petritakis, Spyros. 2018. “The ‘Figure in the Carpet’: M. K. Čiurlionis and the Synthesis of the Arts.” In Studies in Music, Art and Performance from Romanticism to Postmodernism: The Musicalisation of Art, edited by Diane Silverthorne. New York: Bloomsbury Academic Publishing [forthcoming].

Petritakis, Spyros. 2016. “Quand le miroir devient lampion: aspects de la réception de l’œuvre tardive de Nikolaus Gysis entre Athènes et Munich.” Pp. 71-97 in Quêtes de modernité(s) artistique(s) dans les Balkans au tournant du XX e siècle, edited by Catherine Méneux and Adriana Sotropa, conference proceedings, November 8-9, Université Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne, site de l’HiCSA et du centre François-Georges Pariset, Paris 2013. Accessed from http://hicsa.univ-paris1.fr/documents/pdf/PublicationsLigne/Colloque%20Balkans/04_petritakis.pdf on 30 March 2017.

Petritakis, Spyros. 2014. “The Reception of Nikolaos Gyzis’s ‘Behold, the Bridegroom Cometh’ by Rudolf Steiner in 1910 in Munich: Its Ideological Premises and Echo.” Paper presented at the conference Western Esotericism in East-Central Europe over the Centuries, Budapest, July 4, 2014.

Petritakis, Spyros. 2013. “‘Through the Light, the Love’: The Late Religious Work of Nikolaos Gyzis (1842-1901) Under the Light of the Theosophical Doctrine in Munich in the 1890s.” Paper presented at the conference Enchanted Modernities: Theosophy and the Arts in the Modern World, Amsterdam, September 25, 2013.

Picht, Carlo Septimus. 1951. “Nikolaus Gysis. Zum Gedenken an Seinem 50. Todestag (January 4, 1951).” Pp. 419-21 in Blätter für Anthroposophie 3, no. 12.

Steiner, Rudolf. 1951. “Aus dem Lichte die Liebe.” Pp. 421-26 in Blätter für Anthroposophie 3:12.

Strakosch-Giesler, Maria. 1955. Die Erlöste Sphinx. Über die Darstellung der menschlichen Gestalt in Bild- und Glanzfarben. Freiburg: Novalis – Verlag.

Zander, Helmut. 2007. Anthroposophie in Deutschland: Theosophische Weltanschauung und Gesellschaftliche Praxis, 1884-1945, Two Volumes. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Zander, Helmut. 1998. “Ästhetische Erfahrung: Mysterientheater von Edouard Schuré zu Wassily Kandinsky.” Pp. 203-21 in Mystique, Mysticisme et Modernité en Allemagne autour de 1900, edited by Moritz Bassler and Hildegard Chatellier. Conference Proceedings, University of Strasbourg, 1996. Strasbourg: Presses Universitaires de Strasbourg.

Post Date:

17 April 2017

Grand Master Hun Yuan [Image at right] is one of these founders of religious movements who also emerged as significant artists in their own merit. In this sense, he can be compared to Oberto Airaudi, who founded Damanhur in Italy (Zoccatelli 2016), and to Adi Da Samraj (Franklin Jones), the leader and founder of Adidam in the United States (Bradley-Evans 2017). Like Airaudi and Adi Da, Hun Yuan is revered as the founder of a new religious movement by his followers, while on the other hand his artwork is appreciated even by artists and critics who are not interested in joining his group (see Carbotti 2017).

Grand Master Hun Yuan [Image at right] is one of these founders of religious movements who also emerged as significant artists in their own merit. In this sense, he can be compared to Oberto Airaudi, who founded Damanhur in Italy (Zoccatelli 2016), and to Adi Da Samraj (Franklin Jones), the leader and founder of Adidam in the United States (Bradley-Evans 2017). Like Airaudi and Adi Da, Hun Yuan is revered as the founder of a new religious movement by his followers, while on the other hand his artwork is appreciated even by artists and critics who are not interested in joining his group (see Carbotti 2017). development of the worldview and divination method taught in the Chinese classic book I Ching. [Image at right]

development of the worldview and divination method taught in the Chinese classic book I Ching. [Image at right] architects who are not part of Weixin Shengjiao, but his main achievement are the movement’s temples, including the headquarters in Nantou County [Image at right] and two Cities of Eight Trigrams, one in Taiwan and one in Henan, China. Grand Master Hun Yuan would however deny that considerations about Feng Shui and aesthetics are part of two separate realms. He teaches that what is in accordance with Feng Shui conveys an image of harmony, and as such is also beautiful.

architects who are not part of Weixin Shengjiao, but his main achievement are the movement’s temples, including the headquarters in Nantou County [Image at right] and two Cities of Eight Trigrams, one in Taiwan and one in Henan, China. Grand Master Hun Yuan would however deny that considerations about Feng Shui and aesthetics are part of two separate realms. He teaches that what is in accordance with Feng Shui conveys an image of harmony, and as such is also beautiful. vitality.” He spent the whole day painting The Golden Dragon of Fulfilled Wishes with a heavy brush. [Image at right] In the end, he did not feel tired, which he interpreted as an auspicious sign (Hun Yuan 2007:2). In the meantime, he had also inaugurated a distinctive style of painting, and he would never look back.

vitality.” He spent the whole day painting The Golden Dragon of Fulfilled Wishes with a heavy brush. [Image at right] In the end, he did not feel tired, which he interpreted as an auspicious sign (Hun Yuan 2007:2). In the meantime, he had also inaugurated a distinctive style of painting, and he would never look back. “blessing of all holy deities” emanating from the painting (Hun Yuan 2017:25). [Image at right]

“blessing of all holy deities” emanating from the painting (Hun Yuan 2017:25). [Image at right] reproduced example is The Stable Nation of the Golden Dragon, admired by critics but also regarded as a sacred painting by devotees. [Image at right]

reproduced example is The Stable Nation of the Golden Dragon, admired by critics but also regarded as a sacred painting by devotees. [Image at right] comments at the Exhibition of Zen, held at Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hall in Taipei in 2000. [Image at right] While he was almost ready to sell the paintings, which were exhibited outdoor, “it suddenly rained and the six pieces […] were all wet and blurred. At that moment, Grand Master Hun Yuan Chanshi realized the underlying meaning, ‘No sale!’ instructed by Buddha” (Huang 2011:16). The incident typically captures the dilemma whether these sacred artifacts should be considered “works of art” in the sense in which this expression is commonly understood in the twenty first century. But this is a problem common to all genuinely religious art, particularly when it is produced mostly for the internal purpose of beautifying the devotees’ homes and the movement’s places of worship.

comments at the Exhibition of Zen, held at Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hall in Taipei in 2000. [Image at right] While he was almost ready to sell the paintings, which were exhibited outdoor, “it suddenly rained and the six pieces […] were all wet and blurred. At that moment, Grand Master Hun Yuan Chanshi realized the underlying meaning, ‘No sale!’ instructed by Buddha” (Huang 2011:16). The incident typically captures the dilemma whether these sacred artifacts should be considered “works of art” in the sense in which this expression is commonly understood in the twenty first century. But this is a problem common to all genuinely religious art, particularly when it is produced mostly for the internal purpose of beautifying the devotees’ homes and the movement’s places of worship.

viewer a sense of incompleteness. With his series of drawings made with Indian ink on photographic foil, intended to be seen in front of a light source (a technique invented by Gyzis himself) the painter was hinting at an otherworldly universe, like the one explored by Spiritualist mediums. [Image at right] Similarly, the sketches in black paper with white chalk, that he produced, in 1898, with Anna May’s aid (Drosinis 1953:235), evoke the idea of a juxtaposition between an earthly reality and a spiritual otherness. The latter were bought from the Bavarian Government and are now kept in Staatliche Graphische Sammlung in Munich.

viewer a sense of incompleteness. With his series of drawings made with Indian ink on photographic foil, intended to be seen in front of a light source (a technique invented by Gyzis himself) the painter was hinting at an otherworldly universe, like the one explored by Spiritualist mediums. [Image at right] Similarly, the sketches in black paper with white chalk, that he produced, in 1898, with Anna May’s aid (Drosinis 1953:235), evoke the idea of a juxtaposition between an earthly reality and a spiritual otherness. The latter were bought from the Bavarian Government and are now kept in Staatliche Graphische Sammlung in Munich.

Asked about Jean Delville (1867-1953), [Image at right] many contemporary Belgians would simply answer: “Delville, never heard of him!” However, when paintings such as the Portrait of Madame Stuart Merrill (now at the Brussels Museum of Fine Arts), The School of Plato (at Paris’ Musée d’Orsay), or The Love of Souls (at the Museum of Ixelles, Brussels), are mentioned, many would recognize them as iconic symbolist works. His works survive, and position Delville among the great symbolist painters. But Delville the man has disappeared and his works, in a way, have been taken hostage by critics in such a way as to make their author invisible. In part, Delville himself is to blame: a brilliant artist and intellectual, but difficult in person, he was known to practice “the delicate art of making enemies.” His family and descendants also shoulder some of the blame, having fashioned a sanitized, official version of his tumultuous life, which cared little for his esoteric inclinations and glossed over him leaving his family at the age of sixty-seven to live with a young student, Émilie Leclercq (1904-1992).

Asked about Jean Delville (1867-1953), [Image at right] many contemporary Belgians would simply answer: “Delville, never heard of him!” However, when paintings such as the Portrait of Madame Stuart Merrill (now at the Brussels Museum of Fine Arts), The School of Plato (at Paris’ Musée d’Orsay), or The Love of Souls (at the Museum of Ixelles, Brussels), are mentioned, many would recognize them as iconic symbolist works. His works survive, and position Delville among the great symbolist painters. But Delville the man has disappeared and his works, in a way, have been taken hostage by critics in such a way as to make their author invisible. In part, Delville himself is to blame: a brilliant artist and intellectual, but difficult in person, he was known to practice “the delicate art of making enemies.” His family and descendants also shoulder some of the blame, having fashioned a sanitized, official version of his tumultuous life, which cared little for his esoteric inclinations and glossed over him leaving his family at the age of sixty-seven to live with a young student, Émilie Leclercq (1904-1992). Louvain, Belgium, on January 19, 1867. His family subsidized his evening classes at the Brussels Academy of Fine Arts, where he got his diploma in 1887. He led a charmed life, having by the tender age of twenty produced such masterpieces as L’Homme aux corbeaux, recently rediscovered in the dusty archives of the Belgian Royal Library [Image at right]. Still in his youth, he collaborated with L’Essor, one of the best-known art salons in Belgium. In 1892, he established in Brussels his own salon, Pour l’Art, followed in 1895 by a new salon, devoted to what he called “Idealist art.” In the same year 1895, he won the prestigious Prix de Rome in the category of painting. In 1897, he produced his first masterpiece, The School of Plato [Image at right]. He also published books, both of esoteric poetry and about art, starting with Les Horizons hantés in 1893 (Delville 1893) and Le Frisson du Sphinx in 1897 (Delville 1897), and culminating in 1900 with The New Mission of Art (Delville 1900),

Louvain, Belgium, on January 19, 1867. His family subsidized his evening classes at the Brussels Academy of Fine Arts, where he got his diploma in 1887. He led a charmed life, having by the tender age of twenty produced such masterpieces as L’Homme aux corbeaux, recently rediscovered in the dusty archives of the Belgian Royal Library [Image at right]. Still in his youth, he collaborated with L’Essor, one of the best-known art salons in Belgium. In 1892, he established in Brussels his own salon, Pour l’Art, followed in 1895 by a new salon, devoted to what he called “Idealist art.” In the same year 1895, he won the prestigious Prix de Rome in the category of painting. In 1897, he produced his first masterpiece, The School of Plato [Image at right]. He also published books, both of esoteric poetry and about art, starting with Les Horizons hantés in 1893 (Delville 1893) and Le Frisson du Sphinx in 1897 (Delville 1897), and culminating in 1900 with The New Mission of Art (Delville 1900),  published with a preface by the famous Theosophist Édouard Schuré (1841-1929) and translated into English in 1910 (Delville 1910).

published with a preface by the famous Theosophist Édouard Schuré (1841-1929) and translated into English in 1910 (Delville 1910). member of Kumris (or Kvmris), the Belgian branch of Papus’ French Groupe indépendant d’études ésotériques, and an organization that was an art salon and an occult circle at the same time.

member of Kumris (or Kvmris), the Belgian branch of Papus’ French Groupe indépendant d’études ésotériques, and an organization that was an art salon and an occult circle at the same time. 1900 and 1907, such as The God-Man, Love of Souls [Image at right], and Prometheus, were inspired by the occult, from his artistic subjects to the form, colors and symbols he used. Symbolism in general combined aesthetics and esotericism, particularly in France and Belgium. Jean Delville became one of its main representatives, along with the other Belgian symbolists, such as Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921) and Félicien Rops (1833-1898), and the French painters, particularly influenced by Theosophy and Schuré, known as the Nabis.

1900 and 1907, such as The God-Man, Love of Souls [Image at right], and Prometheus, were inspired by the occult, from his artistic subjects to the form, colors and symbols he used. Symbolism in general combined aesthetics and esotericism, particularly in France and Belgium. Jean Delville became one of its main representatives, along with the other Belgian symbolists, such as Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921) and Félicien Rops (1833-1898), and the French painters, particularly influenced by Theosophy and Schuré, known as the Nabis. conferences (Delville 1913; 1925; 1928) [Image at right]. This would go on until Krishnamurti reached adulthood and disavowed his role in 1929, by declaring that he was neither the World Teacher nor a new Christ. For Delville, this marked a defeat, depression, and rupture.

conferences (Delville 1913; 1925; 1928) [Image at right]. This would go on until Krishnamurti reached adulthood and disavowed his role in 1929, by declaring that he was neither the World Teacher nor a new Christ. For Delville, this marked a defeat, depression, and rupture. the Academy’s bulletins, were written in Mons. As a painter, he also remained very active, rediscovering his creativity and producing some inspired Art Deco works, which today come as a surprise for those who know Delville when they learn of them, only because they were so neglected. In Mons [Image at right], Delville would produce several masterpieces in terms of the talent imbued in them and their scope, particularly the superb Roue du Monde, which is the property of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, although unfortunately preserved in its reserve rather than displayed. As a citizen, too, he showed vivaciousness as a resistant against the occupying German forces, releasing deliberately contrarian works under the Nazis’ very noses.

the Academy’s bulletins, were written in Mons. As a painter, he also remained very active, rediscovering his creativity and producing some inspired Art Deco works, which today come as a surprise for those who know Delville when they learn of them, only because they were so neglected. In Mons [Image at right], Delville would produce several masterpieces in terms of the talent imbued in them and their scope, particularly the superb Roue du Monde, which is the property of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, although unfortunately preserved in its reserve rather than displayed. As a citizen, too, he showed vivaciousness as a resistant against the occupying German forces, releasing deliberately contrarian works under the Nazis’ very noses. sculptor. Harvent observed Delville’s paintings in his workshop every day and took notes. In 1944, he watched him painting his famous Portrait of Madame Stuart Merrill, which the official biographies of Delville, as well as the Brussels Museum of Fine Arts, date back to 1892. Not so, claimed Harvent: it was painted in front of him in 1944 (note in the René Harvent archive, reproduced in Guéguen 2016:214).

sculptor. Harvent observed Delville’s paintings in his workshop every day and took notes. In 1944, he watched him painting his famous Portrait of Madame Stuart Merrill, which the official biographies of Delville, as well as the Brussels Museum of Fine Arts, date back to 1892. Not so, claimed Harvent: it was painted in front of him in 1944 (note in the René Harvent archive, reproduced in Guéguen 2016:214). century (Laoureux 2014; Larvová 2015). A true academic study of Derville also started fairly recently (see Cole 2015), particularly with respect to his connections with Theosophy and esotericism (Clerbois 2012; Gautier 2011; Gautier 2012; Introvigne 2014; Guéguen 2016, 2017). Further studies on Delville the poet, Delville the musician, and Delville the art critic would hopefully follow.

century (Laoureux 2014; Larvová 2015). A true academic study of Derville also started fairly recently (see Cole 2015), particularly with respect to his connections with Theosophy and esotericism (Clerbois 2012; Gautier 2011; Gautier 2012; Introvigne 2014; Guéguen 2016, 2017). Further studies on Delville the poet, Delville the musician, and Delville the art critic would hopefully follow. interpreted through political and feminist lenses, while the influence of Western esotericism has not been properly discussed. However, from the very beginning, Abramović’s art has been significantly affected by the New Age and other contemporary “alternative” spiritualities. In the period of her joint work with German artist Ulay (Frank Uwe Laysiepen, b. 1943), these esoteric pursuits became even more prominent. Later in her career, she came to present her performance art, which increasingly included the participation of the public, as a kind of spiritual practice. Eventually, she developed The Abramović Method, a syncretic mind-body-spirit training program for her followers, which drew on different sources such as New Age, the Armenian esoteric master George Ivanovich Gurdjieff (1866?-1949), vipassana meditation, Brazilian Spiritualism, and others.

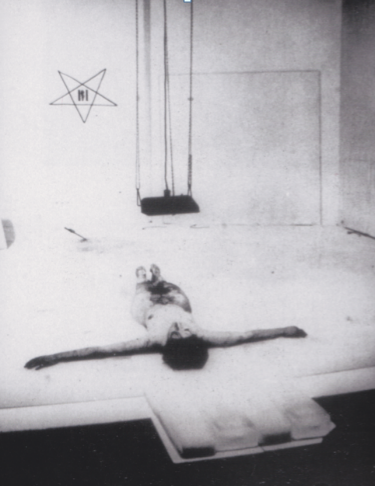

interpreted through political and feminist lenses, while the influence of Western esotericism has not been properly discussed. However, from the very beginning, Abramović’s art has been significantly affected by the New Age and other contemporary “alternative” spiritualities. In the period of her joint work with German artist Ulay (Frank Uwe Laysiepen, b. 1943), these esoteric pursuits became even more prominent. Later in her career, she came to present her performance art, which increasingly included the participation of the public, as a kind of spiritual practice. Eventually, she developed The Abramović Method, a syncretic mind-body-spirit training program for her followers, which drew on different sources such as New Age, the Armenian esoteric master George Ivanovich Gurdjieff (1866?-1949), vipassana meditation, Brazilian Spiritualism, and others. 1974), during the III April Meetings in the SKC [Image at right]. Abramović doused with gasoline and lit a big wooden construction in the shape of what was easily recognized as the petokraka (“five-pointed star of Socialism ” in Serbian), a symbol of the regime. Abramović cut her hair, finger and toe nails, and threw them into the fire. Then she laid down in the blazing star, thus evoking the famous drawing of a man inscribed in a pentagram, from the book by Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa (1486-1535) De occulta philosophia (1533). Finally, she lost consciousness due to the lack of oxygen, and was saved from the flames by her colleagues.

1974), during the III April Meetings in the SKC [Image at right]. Abramović doused with gasoline and lit a big wooden construction in the shape of what was easily recognized as the petokraka (“five-pointed star of Socialism ” in Serbian), a symbol of the regime. Abramović cut her hair, finger and toe nails, and threw them into the fire. Then she laid down in the blazing star, thus evoking the famous drawing of a man inscribed in a pentagram, from the book by Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa (1486-1535) De occulta philosophia (1533). Finally, she lost consciousness due to the lack of oxygen, and was saved from the flames by her colleagues. Innsbruck, Austria. [Image at right] The performance started with the “Eucharist,” in which she sat naked at a table, ate one jar of honey, and drank one bottle of red wine. Then she drew on the wall an inverted pentagram around the photography of Thomas Lips, a young Swiss man she wanted to seduce (Stokić 2008:42-44), cut the same inverted pentagram on her belly with a razor-blade, flagellated herself until she started to bleed, and finally “crucified” herself on a cross made of ice blocks.

Innsbruck, Austria. [Image at right] The performance started with the “Eucharist,” in which she sat naked at a table, ate one jar of honey, and drank one bottle of red wine. Then she drew on the wall an inverted pentagram around the photography of Thomas Lips, a young Swiss man she wanted to seduce (Stokić 2008:42-44), cut the same inverted pentagram on her belly with a razor-blade, flagellated herself until she started to bleed, and finally “crucified” herself on a cross made of ice blocks. a series of performances in which they ran towards each other and collided at high speed (Relation in Space 1976), or spent hours with their long hairs tied together (Relation in Time 1977). [Image at right] In one interview from that time, Abramović said: “I feel the perfect human being is a hermaphrodite, because it’s half man, half woman, yet it’s a complete universe” (Kontova 1978:43).

a series of performances in which they ran towards each other and collided at high speed (Relation in Space 1976), or spent hours with their long hairs tied together (Relation in Time 1977). [Image at right] In one interview from that time, Abramović said: “I feel the perfect human being is a hermaphrodite, because it’s half man, half woman, yet it’s a complete universe” (Kontova 1978:43). her Transitory Objects. These furniture-like objects, which she has been producing since 1988, are usually made by using crystals, copper, or magnets, materials which, according to Abramović, emanate an “energy” capable of healing or spiritually transforming the user. Abramović invites her public to sit, stand or lie on the exhibited Transitory Objects, eyes closed, without moving, in a way similar to what is done in vipassana meditation [Image at right]. According to Abramović, the purpose of her Transitory objects is to help her followers in their spiritual development. When humanity would reach the sought-for spiritual transformation, no objects would be necessary, and that is why she calls them “transitory.” Abramović presents her work with the Transitory objects only as the first phase in the spiritual evolution of her audience. The final goal is to reach the “higher level of consciousness” that will enable the audience to receive the thoughts and “energy” directly from her, by means of telepathy (Art Meets Science 2013).

her Transitory Objects. These furniture-like objects, which she has been producing since 1988, are usually made by using crystals, copper, or magnets, materials which, according to Abramović, emanate an “energy” capable of healing or spiritually transforming the user. Abramović invites her public to sit, stand or lie on the exhibited Transitory Objects, eyes closed, without moving, in a way similar to what is done in vipassana meditation [Image at right]. According to Abramović, the purpose of her Transitory objects is to help her followers in their spiritual development. When humanity would reach the sought-for spiritual transformation, no objects would be necessary, and that is why she calls them “transitory.” Abramović presents her work with the Transitory objects only as the first phase in the spiritual evolution of her audience. The final goal is to reach the “higher level of consciousness” that will enable the audience to receive the thoughts and “energy” directly from her, by means of telepathy (Art Meets Science 2013). students were instructed to move as slowly as possible while performing their everyday activities. In another exercise, Counting the Rice, students were given piles of uncooked rice mixed with lentils, with an assignment to separate the grains and count them, which usually took several hours [Image at right].

students were instructed to move as slowly as possible while performing their everyday activities. In another exercise, Counting the Rice, students were given piles of uncooked rice mixed with lentils, with an assignment to separate the grains and count them, which usually took several hours [Image at right]. Brazil in 2012/2013. One of the most important teachers Abramović met there was

Brazil in 2012/2013. One of the most important teachers Abramović met there was  supposedly generating the mysterious “current” through their contacts with the audience, as it was announced in the catalogue of the performance (O’Brien 2014:16). Abramović and her assistants gently whispered to every visitor to close their eyes, and to “be in the present,” while they were leading them by the hand in the gallery and instructing them what to do next Abramović and her assistants also laid their hands “reiki-like” on the visitors’ backs [Image at right], as if they were manipulating some kind of “energy.” The activities at the exhibition were not the same during the sixty-four days, as Abramović experimented to find out which of the exercises produced more “energy” there. Some of these exercises were later incorporated in new versions of The Abramović Method presented in São Paolo (2015), Sydney (2015), and Athens (2016). In these new versions of her Method, Abramović also introduced some of the exercises from the Cleaning the House student workshop mentioned before.

supposedly generating the mysterious “current” through their contacts with the audience, as it was announced in the catalogue of the performance (O’Brien 2014:16). Abramović and her assistants gently whispered to every visitor to close their eyes, and to “be in the present,” while they were leading them by the hand in the gallery and instructing them what to do next Abramović and her assistants also laid their hands “reiki-like” on the visitors’ backs [Image at right], as if they were manipulating some kind of “energy.” The activities at the exhibition were not the same during the sixty-four days, as Abramović experimented to find out which of the exercises produced more “energy” there. Some of these exercises were later incorporated in new versions of The Abramović Method presented in São Paolo (2015), Sydney (2015), and Athens (2016). In these new versions of her Method, Abramović also introduced some of the exercises from the Cleaning the House student workshop mentioned before. Gaga, and that she danced with rapper Jay Z, both of whom are believed by conspiracy theorists to be involved with the secret world government of the “Illuminati,” only added fuel to the fire. It should be added that Abramović had indeed been playing with magic and perhaps Satanist symbols during an eccentric photo-shoot for the Ukrainian edition of Vogue in 2014. [Image at right] One photo shows her holding a goat head, represented also in the Sigil of Baphomet, whose origins in the system of magic of Éliphas Lévi (1810-1875) were not Satanic but that later was also used as an official symbol of the Church of Satan. Another photo shows her standing behind “butchered” female bodies, as a kind of a sinister priestess. However, there is no evidence that Abramović is in fact a Satanist. According to Massimo Introvigne, “one needs to worship the character called the Devil or Satan in the Bible” to be defined as a Satanist. Abramović has no intentions whatsoever to worship Satan, but simply uses certain symbols that have been used by Satanists as well as by other non-Satanist occult groups, in a different context and often “in a rather playful way” (Introvigne 2016).

Gaga, and that she danced with rapper Jay Z, both of whom are believed by conspiracy theorists to be involved with the secret world government of the “Illuminati,” only added fuel to the fire. It should be added that Abramović had indeed been playing with magic and perhaps Satanist symbols during an eccentric photo-shoot for the Ukrainian edition of Vogue in 2014. [Image at right] One photo shows her holding a goat head, represented also in the Sigil of Baphomet, whose origins in the system of magic of Éliphas Lévi (1810-1875) were not Satanic but that later was also used as an official symbol of the Church of Satan. Another photo shows her standing behind “butchered” female bodies, as a kind of a sinister priestess. However, there is no evidence that Abramović is in fact a Satanist. According to Massimo Introvigne, “one needs to worship the character called the Devil or Satan in the Bible” to be defined as a Satanist. Abramović has no intentions whatsoever to worship Satan, but simply uses certain symbols that have been used by Satanists as well as by other non-Satanist occult groups, in a different context and often “in a rather playful way” (Introvigne 2016).