World Mate

WORLD MATE

WORLD MATE TIMELINE

1934: Uematsu Aiko was born.

1951 (March 18): Handa Haruhisa (aka Fukami Seizan [until 1994] and thereafter Fukami Tōshū) was born in Hyōgo Prefecture.

c. 1960: Handa Shihoko, Fukami’s mother, joined Sekai Kyūseikyō and began to visit its local church with Fukami.

c. 1966: Fukami received from Sekai Kyūseikyō an ohikari locket pendant, which authorised him to perform the movement’s main ritual known as jōrei .

c. 1970: Fukami developed a strong interest in, and then converted to, Oomoto.

1976: Having graduated from Dōshisha University in Kyoto, Fukami started work as a salesperson in Tokyo, and began to visit the Japanese office of the Chinese philanthropic organization World Red Swastika Society.

1977: Fukami met Uematsu at the Japanese office of the World Red Swastika Society.

1978: Uematsu founded the company Misuzu Corporation, and Fukami established the preparatory school Misuzu Gakuen as part of its business.

1984: Uematsu and Fukami established the religious group Cosmo Core.

1985: Cosmo Core changed its name to Cosmo Mate.

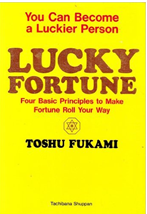

1986: Fukami published his best-selling book Kyōun (Lucky Fortune).

1989: Fukami founded the publisher Tachibana Publishing.

1991: Fukami founded the consulting firm B. C. Consulting.

1993: Two former female members of Cosmo Mate sued Fukami for damages in March, claiming that he acted indecently with them, and reached a settlement in December of that year.

1994 (April): Cosmo Mate changed its name to Powerful Cosmo Mate.

1994 (May and June): Former members sued Fukami and Powerful Cosmo Mate for damages in May and June respectively, claiming that he and the movement defrauded them of a lot of money.

1994 (December): Powerful Cosmo Mate changed its name to World Mate.

1994: The International Shinto Foundation (ISF, New York) and Shinto Kokusai Gakkai (International Shinto Studies Association [formerly known as International Shinto Research Institute], Tokyo) were established.

1995: World Mate began to hold kokubō shingyō gatherings, which aimed to empower Japan’s national defence.

1996 (April): World Mate sued the Shizuoka Prefecture government for not accepting the movement’s application for registration under the Religious Corporation Law.

1996 (May): Tax penalties were imposed by the Ogikubo tax office in Tokyo on the company Cosmo World, which the tax bureau claimed was linked to World Mate.

1996: World Mate provided funds for establishing, and operating, the Sihanouk Hospital Center of Hope, as World Mate and Fukami emphasized practising philanthropy and charity in Cambodia thereafter.

1997: Fukami completed a master’s course in voice at Musashino Academia Musicae, a Japanese college of music.

2001: World Mate and Fukami filed a defamation suit against Noh critic Ōkouchi Toshiteru and the publisher of the magazine psiko. They also made a claim for damages against journalists contributing to, and the publisher of, the magazine Cyzo.

2002: The website Wārudo Meito Higai Kyūsai Netto ワールドメイト被害救済ネット (the title of which translates as “the website that aims to support those who suffer damage caused by World Mate”) was launched by lawyers and journalists.

2005 (January): Fukami stood down from the position of vice president of Shinto Kokusai Gakkai.

2006 (May): At the Tokyo High Court, World Mate obtained a reversal of the tax penalty imposed by the Ogikubo tax office in 1996.

2006: Fukami received a Doctor of Literature at Tsinghua University in China.

2007: Fukami obtained a Doctor of Literature in Chinese Classic Literature degree at Zhejiang University in China.

2008: The Worldwide Support for Development (WSD), a not-for-profit organization chaired by Fukami, was established.

2010: World Mate was the fifth largest donor (and the largest among religious organizations) to political parties and Diet members.

2012: World Mate gained certification as a religious corporation by Japan’s Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

2013-2014: The Global Opinion Leaders Summit, hosted by the WSD, was held three times.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

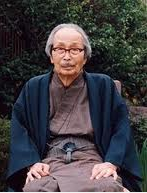

World Mate’s charismatic leader Fukami Tōshū 深見東州 (formerly known as Fukami Seizan 深見青山 ), whose birth name is Handa Haruhisa 半田晴久, [Image at right] was born in Hyōgo Prefecture in 1951. At that time his father, Handa Toshiharu, was still a university student actively involved in left-wing political movements. According to Fukami’s column posted on World Mate’s website, his mother Shihoko, three years older than Toshiharu, was a relative of Toshiharu’s father (i.e. Fukami’s grandfather).

birth name is Handa Haruhisa 半田晴久, [Image at right] was born in Hyōgo Prefecture in 1951. At that time his father, Handa Toshiharu, was still a university student actively involved in left-wing political movements. According to Fukami’s column posted on World Mate’s website, his mother Shihoko, three years older than Toshiharu, was a relative of Toshiharu’s father (i.e. Fukami’s grandfather).

Toshiharu found it quite difficult to get a steady job due to his political activities and therefore could not afford to take care of Shihoko and Fukami. According to Ōhara (1992), in addition to such financial difficulties , his increasingly arrogant attitude and violence towards Shihoko troubled her deeply. As a result, she joined Sekai Kyūseikyō 世界救世教, one of Japan’s largest Shinto-based NRMs (new religious movements), with the hope that Toshiharu would stop his domestic violence.

She made frequent visits to a local Kyūseikyō church with Fukami, which caused him to gradually deepen his faith in the movement. When Fukami was fifteen, he was given an ohikari locket pendant by Kyūseikyō; fifteen is the usual age for bestowing this pendant on members. According to Kyūseikyō, the pendant enables its holder to do the practice of jōrei, a healing art of purifying the spirit by radiating a divine light (ohikari) from the palm.

Although Shihoko sincerely believed in the efficacy of the healing art of jōrei , she suffered an unidentified, serious illness around the end of the 1960s, when Fukami was a high school student. He asked a senior member of Oomoto 大本 to remove the spiritual cause of her illness (Isozaki 1991; Ōhara 1992). Oomoto was a Shinto-based NRM emphasizing healing practices, to which Okada Mokichi, Kyūseikyō’s founder, had belonged prior to establishing his movement. Shihoko subsequently recovered from her illness. Then Fukami visited Matsumoto Matsuko, a female psychic of Oomoto, who, he claimed, led him to become aware of the presence of kami or deity. After entering D ō shisha University in Kyoto in 1972 (Yonemoto 1993; Hasegawa 2015), he became deeply committed to Oomoto.

Fukami received a degree in Economics at Dōshisha in 1976 and started to work at a construction company in Tokyo. Then he visited the Japanese office of the Chinese philanthropic organization World Red Swastika Society, established by the religious movement Tao-yuan. The Red Swastika Society had been on close terms with Oomoto since the 1920s. In its Japanese office located in Tokyo, Fukami displayed an outstanding ability as a saniwa , a spiritual interlocutor or interpreter who claims to be able to judge the authenticity and nature of divine oracles received by mediums. Then, according to Ishizaki (1991) and Ōhara (1992), Su no Kami the Supreme Deity, who was believed in Kyūseikyō to be the creator of the universe, told Fukami to devote himself to the way of Deity (kami no michi) and informed him that a person would come to see him in the near future; Fukami decided to quit his job and deepen his relationship with the Red Swastika Society.

In 1977, a middle-aged woman named Uematsu Aiko 植松愛子 (formerly known as Tachibana Kaoru) visited the Japanese office of the Red Swastika Society. It was the person that Deity had talked to Fukami about, for Uematsu also had been informed by Deity that a young man would come to see her soon. Uematsu, born in 1934, used to be a member of Mahikari 真光 (Yonemoto 1993), which was established in 1959 by Okada Kōtama, a former follower of Sekai Kyūseikyō. After her mother died when Uematsu was thirty-three, she, Fukami claims, received a divine revelation that told her to train her soul through housework and to lead women. Uematsu then organized a personal school for tea ceremony, flower arrangement, and confectionery making ( Ōhara 1992 ), which were traditional women’s arts in Japan. After she met Fukami, her school gradually developed into a small religious group, which had some twenty members (Yonemoto 1993).

While they congregated at her house in the Ogikubo area of Tokyo, Uematsu, who was sponsored by Tsugamura Shigerō, a patent attorney and former member of Mahikari (Yonemoto 1993), formally founded the company Misuzu Corporation in 1978. In practical terms, however, Fukami was the operating force behind the company. In that year he established Misuzu Gakuen みすず学苑 , a preparatory school for potential applicants to high status universities. Eventually he succeeded in running this school, which has become widely known among high-school students in Tokyo.

Although busy with his business, Fukami continued to be engaged in doing religious activities with Uematsu. In 1984, they established the religious group Cosmo Core, which has formally been regarded as the beginning of World Mate. In 1985, they  changed its name to Cosmo Mate. In 1986, Fukami published five books under the pseudonym Fukami Seizan, which enhanced his profile as a leader of the movement. His second book Kyōun 強運 (Fukami 1986b), whose English-edition is entitled Lucky Fortune, [Image at right] sold especially well (According to Tachibana Publishing, a publishing firm established in 1989 by Fukami, more than 1,700,000 copies of the book have been sold). Consequently Cosmo Mate showed rapid growth from the late 1980s to the early 1990s. During this period some other NRMs, such as Aum Shinrikyō and Kōfuku no Kagaku, began to be active in Tokyo and they, along with Cosmo Mate, became increasingly visible and attracted media and public attention. For example, in its January 1993 issue, Bungei Shunj ū , one of the most popular, opinion-shaping magazines in Japan, selected fifty potential reformers from a variety of fields, two of whom were Fukami and the Aum founder, Asahara Shōkō.

changed its name to Cosmo Mate. In 1986, Fukami published five books under the pseudonym Fukami Seizan, which enhanced his profile as a leader of the movement. His second book Kyōun 強運 (Fukami 1986b), whose English-edition is entitled Lucky Fortune, [Image at right] sold especially well (According to Tachibana Publishing, a publishing firm established in 1989 by Fukami, more than 1,700,000 copies of the book have been sold). Consequently Cosmo Mate showed rapid growth from the late 1980s to the early 1990s. During this period some other NRMs, such as Aum Shinrikyō and Kōfuku no Kagaku, began to be active in Tokyo and they, along with Cosmo Mate, became increasingly visible and attracted media and public attention. For example, in its January 1993 issue, Bungei Shunj ū , one of the most popular, opinion-shaping magazines in Japan, selected fifty potential reformers from a variety of fields, two of whom were Fukami and the Aum founder, Asahara Shōkō.

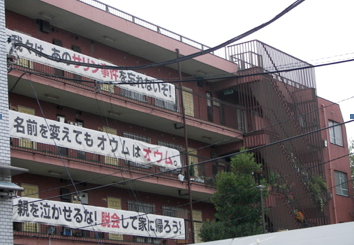

After that, however, the pace of the growth of Cosmo Mate slowed down mainly due to several lawsuits that members or former members brought against Fukami in 1993 and 1994 claiming, for example, sexual harassment and fraudulent activities. Moreover, in December 1993 and in March 1994 the Tokyo Regional Taxation Bureau, suspecting tax evasion, conducted inspections of the company Cosmo Mate (which l ater, around 1995, changed its name to Cosmo World and then later to its present name of Nihon Shichōkaku-sha 日本視聴覚社 ), claiming that this company was related to the religious organization Cosmo Mate. This also worsened the movement’s image. Cosmo Mate (as a religious organization) changed its name to Powerful Cosmo Mate in March 1994, and then to World Mate in December of that year.

Fukami also changed his personal name from Seizan to Tōshū in 1994. In this same year he began to pursue academic studies in Japanese and Chinese religions. In December 1994, Fukami established the International Shinto Foundation (ISF). This non-profit organization has promoted Shinto studies, especially beyond Japan, seeking in particular to promote Fukami’s view of what Shinto studies should be (Antoni 2001). Fukami has in such ways made large donations to universities and colleges abroad, including the School of Oriental and African Studies in London and Columbia University in New York. He has also been awarded a number of honorary and visiting professorships and degrees. Moreover, since the mid-1990s, Tachibana Publishing, run by Fukami, has focused especially on publishing books on classic Zen and Confucianism. Most of these books are written or edited by Japanese scholars. In 2006, Fukami received the degree of Doctor of Literature at Tsinghua University in China. In 2007, Tachibana Publishing published his doctoral thesis, Bijutsu to Shijō 美術と市場 (Fine Arts and their Market). Also in that year, Fukami obtained the degree of Doctor of Literature in Chinese Classic Literature degree at Zhejiang University in China.

In addition to academic studies, Fukami has been increasingly committed to art activities since the 1990s. He has performed as a music composer and arranger, conductor, vocalist, composer of waka and haiku poetry, calligrapher, tea master, flower arrangement master, Noh actor, ballet dancer, and modern stage actor. In 1997, Fukami completed a master’s course in voice at Musashino Academia Musicae, a Japanese college of music. He has licenses to teach Noh plays for the Hōshō School, tea ceremony for the Edo Senke Shinryū School, flower arrangement for the Saga Goryū School, and Japanese calligraphy. Fukami has given these kinds of art performances not only to World Mate members but also to the general public. In 2009, Fukami received an Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from the Julliard School in New York. In 2014, he demonstrated Japanese calligraphy, the art of writing characters with a large fude 筆 (brush), at the British Museum in London.

Furthermore, Fukami has made prophetic pronouncements about a coming crisis that he said would occur in Japan in the near future, and emphasised the need to prevent this. In February 1995, a month after the Hanshin-Awaji great earthquake of January, and before Aum Shinrikyō’s sarin attack on the Tokyo subway system in March, World Mate held kokubō shingyō 国防神業 gatherings, or gatherings for Shinto-style rituals that aimed to empower Japan’s national defence. These drew on the spiritual message Fukami said he had received from the female Oomoto founder, Deguchi Nao, that Japan would face an impending crisis. In the later part of the 1990s, kokubō shingyō gatherings became regarded as one of the most crucial events within the movement.

In the early years of this century, World Mate developed the aim of establishing a World Federal Government in Japan by the year 2020, for Fukami maintained that Japan, as a spiritual centre of the world, would play a critical role in achieving world peace. According to Fukami, unless this World Federal Government was realised, Miroku no yo (Age of Miroku) or Paradise on Earth, would not come. However, he abandoned the goal of founding the Government by 2020. He feared that if he tried to carry this plan out, it would bring about a catastrophic natural disaster and mass deaths provoked by deities seeking to assist in the establishment of this Government.

In the earlier part of the 1990s, World Mate had sought to legally register itself as shūkyō hōjin 宗教法人 (religious corporation) under the 1952 Religious Corporation Law. It made this application to the government of Shizuoka Prefecture, where its headquarters was located. However, at this juncture the government did not accept the application, for it doubted that activities of World Mate, regarded as closely related to the company Nihon Shichōkaku-sha , were totally religious (according to Asahi Shimbun, April 19, 1996, Shizuoka edition; Shizuoka Shimbun, May 17, 1996, Evening edition).

Moreover, in the early 2000s, World Mate faced various accusations. With the rapid growth of the Internet at the time, a large number of self-described, existing and former members argued for and against World Mate and Fukami within cyberspace. For example, in 2002, several journalists and lawyers launched a website attacking the movement on behalf of those who, they claimed, had suffered damage at the hands of World Mate. Although World Mate claimed to be suffering a lot of groundless calumnies and rumours on the Internet, these accusations inevitably damaged its image.

Nevertheless, after a renewed application, in 2012 World Mate was successful in gaining certification as a religious corporation from the Cultural Affairs Agency (the section within Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in charge of administering religious corporations). Little reliable information has been available about why World Mate was approved as a religious corporation in that year. It, however, might be that, due to the Supreme Court’s decision made on May 22, 2006 that Nihon Shichōkaku-sha was not related to World Mate (Handa 2006), the movement’s activities formally came to be seen as religious.

There have been some suggestions that Shimomura Hakubun, a former Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, might have had an influence in this decision of the Cultural Affairs Agency. This, at least, was the implication behind the claim made in the April 16, 2015 issue of Shūkan Bunshun, a weekly magazine with one of the largest circulations in Japan. The magazine reported that some companies established by Fukami, including Tachibana Publishing, had donated three million yen to Shimomura in 2005, a year when Shimomura was serving either as Minister (Monbu Kagaku Daijin Seimukan 文部科学大臣政務 ) or as a Parliamentary Secretary for Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. The magazine also claimed that World Mate had donated three million yen to Shimomura in 2009. Given that weekly magazines in Japan have a reputation for using questionable sources for their stories and for not always being reliable, these claims remain unverified. However, they have contributed to a wider perception, fuelled by parts of the mass media, that World Mate’s activities may not be restricted solely to the realms of religious practice.

After registering with the government as a religious corporation in 2012, World Mate, Fukami Tōshū in particular, considerably enhanced its media visibility by placing frequent, spectacular advertisements of his books and events in national newspapers. In addition, for the past several years World Mate has become active in making large donations to several influential politicians (Hasegawa 2015), while Fukami has emphasized inviting these politicians to various events focusing on him. Although World Mate has postponed its plan of establishing a World Federal Government in Japan, it appears to have developed a policy of seeking to enhance its influence in the Japanese political world.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

World Mate claims itself to be a Shinto-based movement. Nevertheless, its leader, Fukami Tōshū, shows interest in various religions, including not only Shinto but also Buddhism and Confucianism, as is common among many other founders of Japanese NRMs. Moreover, he has published widely on a variety of themes from religion to divination, business and management, education, comedies, romances, and fine art. Therefore, it is quite difficult to give a clear description of his teachings.

However, in many of these writings, including those apparently unrelated to religion, Fukami has repeatedly emphasised that any of our daily activities should be carried out as shingyō 神業, or divine practices whereby one can train one’s soul, and that one could cultivate one’s good fortune through such practices. In fact, World Mate has encouraged followers to do the practice of shingyō and to understand its meanings.

According to Fukami, one’s fortune mainly depends on the karma (in’nen 因縁) of both/either one’s ancestors and/or oneself in one’s previous life. He also states that one is born into a family of good fortune because one did a number of good deeds to save others in one’s previous life (Fukami 1986a). By contrast, those who consider themselves out of luck, Fukami argues, should bear in mind that their improper conduct in their former lives has resulted in their misfortune in this world. Fukami, therefore, suggests that in order to have good fortune, individuals should break their connection with their bad karma (Fukami 1986a).

Japanese NRMs have commonly developed the classic Indian notion of karma in ways that highlight its moral dimensions (Kisala 1994). In this context, Fukami’s view of karma is not uncommon among Japanese NRMs. He maintains that since karma is inherent in the human mind and conduct, individuals should reform themselves so as to break away from their bad karma (Fukami 1987). The best method of cutting off one’s bad karma is to cultivate virtue by acting on behalf of others.

However, in order to completely cut off one’s bad karma, according to Fukami, one needs to not only cultivate virtue but also to worship one’s ancestors. In the middle of every August, World Mate, although it is a Shinto-based movement, holds a Buddhist memorial service for its members’ ancestors, called go-senzo tokubetsu dai-hōyō ご先祖特別 大法要, focusing on a magical ritual Fukami performs for the purpose of saving, or reforming, the spirits of participants’ ancestors linked to their bad karma. Such a view of the potential variability of karma through the practice of ancestor worship mainly derives from the tradition of Japanese folk religion rather than from Buddhism.

World Mate regards the ultimate goal of a person’s life as attaining the state of shinjin gōitsu 神人合一, or oneness with kami or a deity. Fukami (1987) claims that, in contrast to the paternal relationship between God and humans in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, humans can have a friendly relationship with deities in the divine world of Japan. In order to achieve the state of oneness with kami, it is important to maintain a good relationship with them by cultivating virtue, for deities are pleased with a person’s virtue cultivation. According to Fukami (1986b), however, many Japanese people have the wrong idea that self-oriented shugyō 修行 or ascetic practices are required to attain the state of oneness with kami. He claims that religious austerities drain people of their physical power and undermine the vigour of their souls, and that those who practise self-oriented shugyō tend to be possessed by evil spirits. Fukami calls this kind of ascetic exercise kōten no shugyō 後天の修行 (posterior practice), while he recommends doing senten no shugyō 先天の修行 (anterior practice) by which a person pleases kami (Fukami 1986b; 1986c).

By senten no shugyō, Fukami means the daily practice of obeying the moral principle of makoto 誠 (sincerity), which tells people to be unselfish and free from greed (mushi muyoku 無私無欲) (Fukami 1986c), and, in other words, to devote themselves entirely to the service of others and do what others are reluctant to do. Fukami regards self-oriented ascetic practices, including not only shugyō in Buddhism but also misogi 禊 (cold water purification practices) in Shinto, as meaningless. According to him, people find it much more difficult to obtain merits (kudoku 功徳) through such self-oriented practices, than working tirelessly for others in their everyday lives. These merits are materialised in the spiritual world after one’s death and the amount of merits earned becomes an important indicator of whether one is sent by kami to heaven or hell.

The spiritual world is the place to which humans move after their death and departure from this material world. It consists of three realms: heaven, hell, and chūyū reikai 中有霊界, located between heaven and hell (Fukami 1986a). Such a view of the spiritual world is similar to that of the movements, Oomoto and Sekai Kyūseikyō, that Fukami was initially involved with.

The realm to which a dead person goes depends on what that person did in the present world. Fukami (1986a) indicates the conditions under which a dead person can ascend to heaven. The heavenly world, according to Fukami, also consists of three realms. The lowest one is a place for those who were dedicated to others in this world, or those who showed their profound sincerity through the practices of taise 体施, busse 物施, and hosse 法施 (i.e. voluntary work, material donation, and religious education). The highest realm comprises those who were not only active in religious practices but also materially rich, or those who spent their own wealth for the benefit of society through their true religious faith and who make effective use of their status and honour as a means to save others.

Many of the dead, according to Fukami, are not allowed to ascend to heaven and normally are sent to chūyū reikai, the realm for those who hardly ever did astonishingly good or dreadfully bad deeds; therefore, dead persons in chūyū reikai, are regarded as ordinary ones in the spiritual world. Hell comprises those who did a large number of bad deeds in this world and consists of numerous realms, each of which corresponds to the type of bad deed that the dead person has done in this world. If a dead person in hell completely mended his/her ways, the person could move out of it.

According to Fukami (1987), materially rich persons are much more likely than materially poor ones to be spiritually rich as well. Fukami (1986b) attributes one’s material benefits in this world chiefly to one’s luck, rather than to one’s efforts to make money. Moreover, one’s luck reflects the quality of one’s karma caused originally by one’s soul training in the previous world. Therefore, people in this world should train their souls to improve the quality of their karma that will influence their life in the next world. For these reasons, Fukami encourages his followers to train their souls as senten no shugyō (anterior practice) through a variety of daily activities in the real world.

Consequently Fukami regards seeking material success in this world as a sort of soul-training that leads to potential improvement in the quality of one’s karma. Therefore, Fukami, who is also the president of several companies and a business consultant, emphasises the importance of acquiring wealth as a spiritual act. This kind of idea is similar to that of Ōkawa Ryūhō, the founder of Kōfuku no Kagaku, who places an emphasis on acquiring wealth in this world as a method of soul-training, and who maintains that those achieving great material success in this world are more likely to be sent to heaven in the next world.

Moreover, according to World Mate, Fukami is a philanthropist, who has made large donations to charity while leading a very frugal life. In World Mate, Fukami provides a role model for its members, who, therefore, are expected to work hard to make money, and to spend much time and money doing activities for others.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

World Mate places a primary emphasis on worshipping deities through the practice of shinji 神事, or Shinto-style rituals. It has regularly organized gatherings for shinji either on mountains linked to specific deities or in places near well-known Shinto shrines. Normally thousands of followers attend these gatherings and pray earnestly for deities to forestall terrible crises that, Fukami Tōshū claims, people all over the world, and the Japanese in particular, are facing.

World Mate’s major shinji are: Setsubun shinji 節分神事 (in February) held at the calendric beginning of spring, Golden Week shingyō ゴールデンウィーク神業 (in May) held during the holiday period of early May, O-Bon shingyō お盆神業 (in August) held during the holiday period of mid-August associated with festivals for the dead, Fuji Hakone shingyō 富士箱根神業 (in October) held in a place near the Hakone Shrine close to Mount Fuji, and Ise shingyō 伊勢神業 (in December), World Mate’s largest shinji held from the end of December to the beginning of January in the vicinity of Ise, the location of Japan’s most prominent Shinto shrines.

In these shinji gatherings, Fukami repeatedly requires participants to pray together so that he can receive divine messages from the deity of the mountain or the shrine. Praying is regarded as a highly important practice in World Mate. Its new members are encouraged to attend a seminar called shinpō gotokue nyūmon-hen 神法悟得会入門編, where they are expected to learn the basic method of praying to deities that Fukami has developed. Participants in the seminar are asked to keep secret about the methods taught and not relay them to outsiders.

While many members of World Mate may have learned how to pray to deities, participation in shinji gatherings tends to be chiefly limited to those active followers who give voluntary service to, or make frequent visits to, a local branch office of the movement. In World Mate, it is fairly difficult for ordinary members to develop contacts with other members without joining its local activities; therefore ordinary members appear to be reluctant to participate in such gatherings that normally last until late at night in places far from urban areas. During the practice of shinji, Fukami often maintains that the collective power of its participants’ prayer is not strong enough to receive divine messages, suggesting that a larger number of members should take part in the shinji. In such cases, Fukami tends not to perform magical rituals until or unless thousands of members come to pray together.

By contrast, monthly seminars held in Tokyo are popular among the followers in general. They are broadcast by satellite to World Mate’s local branch offices so that members can attend them throughout Japan. In these monthly seminars, Fukami not only gives a lecture, frequently giving a vocal performance as a singer as well, but also practises magical arts aimed at improving the luck of the attendants. These are something that, Fukami claims, only he is able to do. These magical arts include, for example, dai-kyūrei 大救霊 (a special version of kyūrei, the art of saving evil spirits from suffering torment in hell or from being unable to achieve jōbutsu 成仏 [settling themselves in the spiritual world] and then of changing the evil spirits to good ones) and kettō tenkan 血統転換 (the art of improving one’s bloodline, which aims to modify one’s “spiritual genes,” or one’s ancestors’ karma).

These monthly seminars appear to be occasions of great fun, especially for those ordinary followers who just want to improve their own luck through Fukami’s magical practices. They are also occasions aimed at recruiting and introducing new members to World Mate. Active followers are also expected to take care of such new, ordinary and potential members and to view their role in so doing during the monthly seminars as a form of soul-training, rather than as a form of enjoyment.

In addition to the shinji gatherings and seminars that World Mate organizes, iyasaka no gi 弥栄の儀 is conducted in its local branch offices almost on a daily basis. Iyasaka no gi is a Shinto-style ritual where the participants display their gratitude to deities in front of a Shinto altar and pray for the prosperity of the world, of Japan, and of World Mate members. Moreover, a small festival called shinshin-sai 振神祭 is held once a month in its local offices. While the aim of shinshin-sai is to worship the supreme deity Su, branch members organizing the festival, formally open to the public, tend to, like the monthly seminars mentioned above, emphasise entertaining potential, new, and/or less active members by performing magical practices, which, however, are believed to be much less effective than those done by Fukami himself, and by doing fortune-telling, and holding naorai 直会 , a Shinto-based feast where they consume offerings of food and sake (Japanese rice wine) that have been placed before the deities.

While Fukami performs a variety of magical arts that, he claims, enable one to cut off one’s bad karma and improve one’s luck, active followers of World Mate believe that unless they also cultivate their soul by dedicating themselves to the service of others, his magical arts would not be very effective for their luck. In addition, they tend to make efforts to get internal qualifications in World Mate that, Fukami claims, enable them to perform some magical rites, rather than receiving them from other higher-ranking members. Moreover, they are encouraged to do voluntary work for activities of World Mate as a way of self-cultivation, especially for those of its local branch to which they belong. In addition to their daily work in the wider society outside World Mate, they tend to assist, a few times a week, in the activities of their local branch offices of World Mate, which usually are open in the evening on weekdays, and do voluntary work for various activities of World Mate on weekends. They are encouraged to devote tireless efforts to do these daily activities, and to see any of these activities as being part of shingyō or divine practices, which Fukami claims not only train their souls but also impress deities favourably.

Fukami has published a large number of books, just as have Ōkawa Ryūhō of Kōfuku no Kagaku and many other founders of NRMs, but he, unlike Ōkawa, does not frequently tell his followers to read them. Fukami has often pointed out that, although it may be fun reading books and visiting shrines, anyone can do that without much effort and therefore that deities would not be pleased with such easy practices (Fukami 2002). Instead, he has repeatedly encouraged his followers to do what others are reluctant to do, which would result in polishing their soul. According to Fukami, he learned this idea from Sekai Kyūseikyō and, as a method of polishing his soul, he cleaned the toilet of a local church every morning on his way to high school ( Ōhara 1992). World Mate followers, therefore, are encouraged to work diligently behind the scenes at a local branch office of, and various event sites of, the movement.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The shrine Sumera- ōkami On-yashiro 皇大神御社 serves as the central headquarters of World Mate and is based in Shizuoka  Prefecture. The movement also has fifteen Eria Honbu エリア本部 (area or local headquarters) that are located mainly in large cities in Japan, as well as some 190 local branch offices scattered throughout Japan. These branch offices are operated by its local members largely on a voluntary basis, while Eria Honbu or local headquarters are managed by World Mate’s staff members. It appears, therefore, that these local headquarters play a crucial role in making local branch leaders understand, and carry out, World Mate’s policies.

Prefecture. The movement also has fifteen Eria Honbu エリア本部 (area or local headquarters) that are located mainly in large cities in Japan, as well as some 190 local branch offices scattered throughout Japan. These branch offices are operated by its local members largely on a voluntary basis, while Eria Honbu or local headquarters are managed by World Mate’s staff members. It appears, therefore, that these local headquarters play a crucial role in making local branch leaders understand, and carry out, World Mate’s policies.

The number of World Mate’s members, according to its website, is some 72,000 (in July 2011), but according to Aonuma (2015), Hasegawa (2015), and Ōhira (2016), is some 75,000. No reliable information about the number of staff members is available, for it seems that formally some of the full-time staff members are either employees or board members of the companies run by Fukami Tōshū.

While World Mate’s organization is hierarchical, with Fukami at its apex, it is not highly centralised. In contrast to other large NRMs of Japan, World Mate does not take direct control over the operation of the branches through the dispatch of its full-time staff members. In this sense its branches have a high degree of autonomy.

However, shibu-chō 支部長, or local branch leaders, selected from among the branch members, are required to have appropriate administrative skills to enable them to operate their branches properly. They make efforts to motivate their branch members to do voluntary work for World Mate, participate in shinji gatherings, be engaged in missionary work, and so on. Otherwise, inactive branches could be forced to close or to be merged into one of the nearest branches.

World Mate members do not have any obligations to belong to a particular local branch. In fact, some of them may never have visited a branch office. However, those who want to be deeply committed to World Mate are encouraged to visit a local branch office and join Enzeru-kai エンゼル会 (Angel Society) there. The Angel Society, formally independent of World Mate, comprises the movement’s active followers who belong to a particular local branch and who are expected to do voluntary work for activities of World Mate, especially for those of their local branch. No information about the number of Angel members is available. Inferring from the number of participants in World Mate’s major shinji gatherings, most of whom appear to be Angel members, they are very roughly estimated at 20,000.

Although World Mate’s membership categories can be divided into sei-kai’in 正会員 or full membership and jun-kai’in 準会員 or associate membership, this division seems less important among the active followers than the difference between full membership, including membership of the Angel Society, and any other form of membership. This is clearly because Angels are given “ rights,” rather than “duties,” to do voluntary work for World Mate as a form of shingyō (divine practice) and because they can readily attend shinji gatherings as a genuine member of a particular local branch. Ordinary followers who do not belong to any local branches would find it lonely and uncomfortable to spend hours in the field participating in shinji gatherings. Angel membership is also essential to being elected as a high-ranking member, such as shibu-chō and eria-komitti (a committee member of a local headquarters).

Moreover Angel members are normally encouraged to strive to be shi 師 or internal “masters,” such as kyūrei-shi 救霊師, kuzuryū-shi 九頭龍師, and yakuju-shi 薬寿師. Especially kyūrei-shi are seen as high-ranking masters, for Fukami regards them as his jiki-deshi 直弟子 or immediate disciples. Kyūrei-shi candidates not only are expected to participate in seminars especially for them and learn a lot about how to practise the art of kyūrei there but also are required to train themselves because kyūrei-shi are supposed to often perform the secret art of kyūrei (saving spirits) for about two hours without intermission. The number of kuzuryū-shi was some 4,000 in 2003, although no information about the numbers of kyūrei-shi and yakuju-shi is currently available.

Despite such Angel membership privileges, there are also many who do not join the Angel Society. This seems to be both/either because Angel members tend to spend much time and money (largely, donations in formal terms, including expenditures to various events and services offered by World Mate) being committed to various activities of World Mate and/or because they need to get on with other Angel members of the same local branch. Moreover, even ordinary members who do not join the Angel Society can enjoy a variety of services provided by World Mate, although they might have little interest in shingyō that Fukami sees as being essential to his followers

Besides World Mate, Fukami is involved with and has established a number of other organizations, such as business corporations, including Tachibana Publishing and Misuzu Corporation, and non-profit organizations, including Worldwide Support for Development (WSD), International Shinto Foundation (ISF), International Foundation for Arts and Culture (IFAC), and Tokyo Art Foundation (TAF). World Mate claims to have no or little relation to the operations of these organizations but the extent to which they can be seen as entirely separate from Fukami’s activities with World Mate is unclear. For some members, his involvement in other organizations and the prominence he appears to have achieved through them (for example, with the WSD and the ISF) serve as a sign of his charismatic status and importance, and enhance their interest in his movement. At the same time, his association with organizations, such as ISF that he has helped to establish, has led to concerns about the status of ISF and concerns being raised by some scholars about the links between ISF, Fukami, and World Mate (Antoni 2001).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Since the 1990s, it has been repeatedly pointed out by critics and journalists that it is unclear whether World Mate has financial relationships with commercial companies that are operated by Fukami Tōshū or by its senior officials. It seems that this issue was originally caused by the fact that World Mate’s previous name (Cosmo Core, subsequently Cosmo Mate) was the same as that of the company Nihon Shichōkaku-sha. For example, on November 5, 1991, the newspaper Nikkei Ryūtsū Shimbun referred to Cosmo Mate as a “company” that Fukami organized as a membership society. Moreover, according to World Mate (Handa 2006), a former leading member of the movement and his supporters leaked false information about the tax evasion of the company Cosmo Mate to tax authorities in 2003.

Eventually, the Tokyo Regional Taxation Bureau twice audited the company Cosmo Mate (in December 1993 and in March 1994) on suspicion of failing to report taxable revenues from the activities of the religious group Cosmo Mate. As a result of this audit, the Ogikubo tax office in Tokyo imposed a penalty of some three-billion yen on allegedly undeclared income in May 1996. The company (Nihon Shichōkaku-sha) denied any financial link with the religious group (World Mate) and filed a suit against the director of the Ogikubo tax office and finally obtained a reversal of this tax penalty in May 2006 at the Tokyo High Court.

Despite this, some journalists and lawyers have remained suspicious of the financial transactions that World Mate conducts. It has been reported that World Mate’s annual revenues are some ten-billion yen (Aonuma 2015; Hasegawa 2015) or twelve-billion yen ( Ōhira 2016) and that companies in which Fukami is a major stockholder generate some four-billion yen in total annual sales (Hasegawa 2015) or seven-billion yen ( Ōhira 2016). Meanwhile, Fukami has established, and/or has taken executive positions in, a number of non-profit organizations (NPOs). Fukami, as a director or board member of such organizations, has made large donations to scholarly organizations and activities, cultural and art activities, charities, and influential politicians, and he has organized a variety of public events, concerts, conferences, and exhibitions. It could be inferred from this that a huge amount of money has been spent to carry out all of these things. However, little reliable information has been available about the extent to which World Mate and the companies operated by Fukami or by his followers financially support his activities that are claimed by Fukami and his supporters to be unrelated to World Mate.

While Fukami has shown strong interest in a variety of art activities, his deep involvement with Japanese traditional Noh plays has caused a problem for World Mate. Tachibana Publishing, run by Fukami, published the bimonthly magazine Shin Nōgaku Jānaru 新・能楽ジャーナル (New Journal of Noh ) from 2000 to 2012. This Noh review journal was originally issued as Nōgaku Jānaru (Journal of Noh ) by the small publisher Dengei Kikaku from 1994 to 1999, after which it was published by Tachibana. In 2001, the Noh critic Ōkouchi Toshiteru discussed the background to the change from Dengei to Tachibana in the magazine psiko. In his article he said that Tachibana was closely connected to a jakyō 邪教 (“false religion”). Because he called it jakyō, a term that had been widely used pejoratively against a number of NRMs in Japan in earlier times, World Mate sued him for libel.

In February 2003, the Tokyo District Court ruled against World Mate. In its decision the court ruled that the term jakyō could be used to describe either an unrighteous religion or an unethical religion, and that it was not totally incorrect to describe World Mate in such terms, as a jakyō. In October of that year, World Mate and Ōkouchi finally reached a settlement at the Tokyo High Court. However, the lower court’s decision had effectively labelled World Mate as a “false religion,” a point emphasised by Kitō Masaki, who had been Ōkouchi’s defence counsel. He has referred to the court decision as the jakyō hanketsu 邪教判決 (“false religion” decision) on the website mentioned earlier (see the section on Founder/Group History) that was launched in 2002 by journalists and lawyers. Kitō was one of the lawyers involved in setting up this website.

While many NRMs have faced problems related to scandals and mass media attacks, including allegations of being “false religions” and little more than money-making enterprises, World Mate has perhaps faced more of these problems and attacks than most other NRMs. This is in particular not only because of Fukami’s business activities, which he claims are separate from his religious ones, but also because court judgements such as the one that legitimated the use of the term jakyō in connection with World Mate have made it a particular target for critics. Such issues have affected World Mate’s standing and posed a threat to its membership levels as well as to its capacity for recruiting members.

The rapid spread of the Internet since the late-1990s has increased World Mate’s visibility within cyberspace and created new problems for the movement. It has faced numerous attacks online from a large number of self-described, existing and former followers who, benefitting from the anonymity that the Internet provides, argue for and against World Mate and Fukami on the Internet.

A number of people who claim to be ex-members of World Mate have complained online that World Mate and Fukami have cheated them. Cyberspace attacks have constantly tried to project negative images of World Mate followers as being under the influence of “mind control.” World Mate’s response to such attacks has been to claim that it is suffering a lot of groundless calumnies on the Internet. In August 2002, for instance, immediately after Kitō Masaki and other lawyers had established the aforementioned website that was critical of the movement, World Mate distributed to its members a booklet entitled Hontō no Kamisama wa konna Tokoro ni Oriteiru ! 本当の神様はこんなところに降りている! (True Deity is coming down here!), which focused on the past scandals and troubles that World Mate and Fukami had faced. In this booklet, Fukami stated that the rapid expansion of the Internet had largely changed the circumstances surrounding World Mate, and had enabled groundless rumours and calumnies about the movement to spread like wildfire in cyberspace. He further said that, in order to protect members from such inaccurate rumours and calumnies, World Mate had no choice but to have recourse to the law. In fact, World Mate has sued several ex-members and journalists for libel. As a result, it has also gained a reputation for being a litigious movement.

In the eyes of some, Fukami has gradually developed an interest in politics. World Mate’s political aims, notably that of establishing the World Federal Government in Japan by 2020 (and as an initial step the formation of an Asian Federal Government in Japan by the year 2010), aroused concern in some circles, especially given that these aims seemed to have a highly nationalist dimension to them that, for some, was redolent of pre-war Japanese policies. However, as was noted earlier, World Mate has subsequently retreated from this position, although it continues to express a politicised nationalism that arouses disquiet in some circles.

Since the late-2000s World Mate and some of the companies operated or established by Fukami have made sizable donations to political parties and influential politicians, including, as was mentioned earlier, Shimomura Hakubun. In 2010, World Mate donated thirty-million yen to the People’s New Party (Kokumin Shintō), whose representative was Kamei Shizuka, a well-known politician who had served as Minister for Financial Services from September 2009 to June 2010. Eventually, the movement became the fifth largest donor (and the largest among religious organizations) to political parties and Diet members in 2010. At that time Kamei was also an advisor to B. C. Consulting, a company run by Fukami.

The politician to whom World Mate has made the largest donation appears to be Ozawa Ichirō, the co-founder and representative of the People’s Life Party (Seikatsu no Tō). Ozawa is one of Japan’s most influential and well-known politicians, and his annual income was the largest among party leaders for three consecutive years from 2012 to 2014. World Mate appears to have been a major source of funding for his political activities during that time. Like Kamei, Ozawa received advisory fees from B. C. Consulting (according to Mainichi Shimbun July 2, 2012, Evening edition), while World Mate made large donations to his political organization and the People’s Life Party.

Fukami has emphasised not only making political donations but also holding extravagant conferences that invite world-renowned political figures. For example, the Global Opinion Leaders Summit, hosted by the Worldwide Support for Development (WSD), whose chairman was Fukami, was held three times in 2013 and 2014. Tony Blair (invited twice), Bill Clinton, Colin Powell, John Howard (former Australian Prime Minister), Fidel Valdez Ramos ( former Philippine President ), and more than a dozen other well-known figures were invited to this international conference, while Fukami served as its moderator.

Moreover, influential Japanese politicians have been frequently invited to the events organized by his NPOs that are apparently unrelated to politics, such as art exhibitions hosted by the Tokyo Art Foundation. Notable board members of this incorporated foundation have included such well-known political figures as Kamei, Ozawa, Hatoyama Yukio (former Prime Minister), and his younger brother Hatoyama Kunio (who was also an advisor of B. C. Consulting and who passed away in 2016), all of whom used to be Diet members of the Liberal Democratic Party. Thus Fukami has placed strong emphasis on developing his influence among rather conservative politicians. Such links and financial donations to conservative politicians, along with the movement’s perceived associations with nationalism, continue to be viewed with suspicion by those who are hostile to the movement, and add to its problematic public image.

Many members of World Mate appear to be concerned about who might be a potential successor to Fukami, for he remains unmarried and has no children. In 2010, a daughter of Tsugamura Shigerō, who had initially been a formal representative of World Mate, was married to Fukami’s younger brother. Some expect her to succeed Fukami as the leader of World Mate while others claim that World Mate would not survive without the charismatic leadership of Fukami. It appears that Fukami himself has not yet made an official statement about his successor. This issue will remain a key challenge for the movement in the long term.

IMAGES

Image #1: Photograph of Fukami Tōshū, founder of World Mate.

Image #2: Photograph of Toshu Fukami’s popular book, Lucky Fortune.

Image #3: Photograph the shrine Sumera-ōkami On-yashir in Shizuoka Prefecture that serves as the central headquarters of World Mate.

REFERENCES**

** Note: Some of the information in this profile derives from my field research conducted mainly from 2001 to 2003 and from my PhD thesis: Kawakami, Tsuneo. 2008. “ Stories of Conversion and Commitment in Japanese New Religious Movements: The Cases of Tōhōno Hikari, World Mate, and Kōfuku no Kagaku.” Lancaster University, U.K.

Antoni, Klaus. 2001. “Review: Shinto in History: Ways of the Kami.” Journal of Japanese Studies 27:405–09.

Aonuma, Yōichirō. 2015. “Shinkō shūkyō Wārudo Meito to kyōso Fukami Tōshū.” G2 18:184-209.

Fukami, Toshu. 1987. Make Your Own Luck. Tokyo: Tachibana. English edition: 1997.

Fukami, Tōshū. 2002. Shinbutsu no Kotoga Wakaru Hon. Tokyo: Tachibana.

Fukami, Toshu. 1986a. Divine Powers. Tokyo: Tachibana. English edition: 1998.

Fukami, Toshu. 1986b. Lucky Fortune . Tokyo: Tachibana. English edition: 1998.

Fukami Toshu. 1986c. Divine World. Tokyo: Tachibana. English edition: 1997.

Fukami, Tōshū. n.d. “Anime Songu to Nandemo Bōdāresu Ni Natta Ikisatsu” Accessed from http://www.worldmate.or.jp/about/column.html on 26 August 2016.

Handa, Haruhisa. 2006. “Oshirase.” Accessed from http://www.worldmate.or.jp/faq/answer13.html on 26 August 2016.

Hasegawa, Manabu. 2015. “Shimbun Kōkoku de Yatara Menitsuku Nazo No Otoko: Fukami Tōshū.” Shūkan Gendai 57:162-66.

Isozaki, Shirō. 1991. Fukami Seizan. Tokyo: Keibunsha.

Kisala, Robert A. 1994. “Contemporary Karma: Interpretations of Karma in Tenrikyō and Risshō Kōseikai.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 21:73-91.

Ōhara, Kazuhiro. 1992. Naze Hito wa Kami wo Motomerunoka. Tokyo: Sh ō densha.

Ōhira, Makoto. 2016. “Utatte Odoru Kyōso No Kareina Kane to Jinmyaku.” AERA 29:24-25.

Yonemoto, Kazuhiro. 1993. “Rein ō sha Fukami Seizan no Sugao Wa‘aruku Y ō chien’?” Takarajima 30:34-50.

Author:

Tsuneo Kawakami

Post Date:

14 September 2016

Kōbe. He was adopted by his aunt who had the financial means of sending him to school. He graduated from Waseda High School as the best student in the literature program and enrolled in the English Literature Department of the prestigious Waseda University. After a dramatic love affair, he had to discontinue his academic career and take on various poorly paying jobs. He contracted a venereal disease and, searching for a cure, became interested in traditional and spiritual healing as well as in hypnotism and other spiritual practices that were quite fashionable at that time (Biographies of Taniguchi can be found in Seimei no jissō volumes 19 and 20 and Ono 1995).

Kōbe. He was adopted by his aunt who had the financial means of sending him to school. He graduated from Waseda High School as the best student in the literature program and enrolled in the English Literature Department of the prestigious Waseda University. After a dramatic love affair, he had to discontinue his academic career and take on various poorly paying jobs. He contracted a venereal disease and, searching for a cure, became interested in traditional and spiritual healing as well as in hypnotism and other spiritual practices that were quite fashionable at that time (Biographies of Taniguchi can be found in Seimei no jissō volumes 19 and 20 and Ono 1995). immediately took up his pen and started his magazine Seichō no Ie , official publication of whose first issue in March, 1930 is now regarded as the date of foundation of the new religion Seichō no Ie. Between November, 1929 and September, 1933 Taniguchi received twenty nine divine revelations informing him about the nature of the divine and of human beings, thus laying the foundations of some of Seichō no Ie’s key practices and doctrines (Seichō no Ie Honbu 1980:246-78).

immediately took up his pen and started his magazine Seichō no Ie , official publication of whose first issue in March, 1930 is now regarded as the date of foundation of the new religion Seichō no Ie. Between November, 1929 and September, 1933 Taniguchi received twenty nine divine revelations informing him about the nature of the divine and of human beings, thus laying the foundations of some of Seichō no Ie’s key practices and doctrines (Seichō no Ie Honbu 1980:246-78). founded by widely read, well-educated men with a logically written, abstract yet easy-to-understand doctrine. Taniguchi Masaharu had enjoyed literature and read widely on topics, including Freud, Western theology and philosophies as well as on traditional and scientific schools of medicine (all of which eventually contributed to the formation of Seichō no Ie’s doctrine).

founded by widely read, well-educated men with a logically written, abstract yet easy-to-understand doctrine. Taniguchi Masaharu had enjoyed literature and read widely on topics, including Freud, Western theology and philosophies as well as on traditional and scientific schools of medicine (all of which eventually contributed to the formation of Seichō no Ie’s doctrine). rendered in English as Truth of Life , written in 1932. Seimei no jissō has been translated fully into Portuguese ( A Verdade da Vida ), but only partially into English and even less into other languages. Taniguchi’s second series of books is his eleven-volume Shinri ( 『真理』 , The Truth ) which is an introduction to the doctrine expounded in Seimei no jissō and was first published between 1954 and 1958. Kanro no hōu 『甘露の法雨』 , officially translated into English as Nectarean Shower of Holy Doctrines , is the most important of Seichō no Ie’s four holy sutras. It has been translated into several languages and has recently been published in Braille. Kanro no hōu was divinely revealed to Taniguchi Masaharu by the Bodhisattva Kannon on December 1, 1930. Carrying, reading or copying the sutra are said to evoke miracles, such as unexpected recovery from illnesses and protection during accidents.

rendered in English as Truth of Life , written in 1932. Seimei no jissō has been translated fully into Portuguese ( A Verdade da Vida ), but only partially into English and even less into other languages. Taniguchi’s second series of books is his eleven-volume Shinri ( 『真理』 , The Truth ) which is an introduction to the doctrine expounded in Seimei no jissō and was first published between 1954 and 1958. Kanro no hōu 『甘露の法雨』 , officially translated into English as Nectarean Shower of Holy Doctrines , is the most important of Seichō no Ie’s four holy sutras. It has been translated into several languages and has recently been published in Braille. Kanro no hōu was divinely revealed to Taniguchi Masaharu by the Bodhisattva Kannon on December 1, 1930. Carrying, reading or copying the sutra are said to evoke miracles, such as unexpected recovery from illnesses and protection during accidents. with Sōka Gakkai it is also the largest Japanese new religion outside of Japan. Missionary activities in Brazil began in the mid-1950s when members immigrating to Brazil transmitted their faith to fellow Japanese immigrants. After Taniguchi’s visit to Brazil in 1963, however, missionary efforts turned to non-Japanese as well. Recently, Seichō no Ie’s membership in Brazil (the Brazilian headquarters are Seichō no Ie’s missionary headquarters for all of Latin America) has been estimated at around half a million members, eighty to ninety per cent of whom have no Japanese ancestry ( Carpenter and Roof 1995; Maeyama 1992; Shimazono 1991 ). Although missions to Hawai’i and other parts of the United States began before the Pacific War, membership figures do not compare to those in Brazil and most members are of Japanese descent. There are Seichō no Ie branches in several European countries, such as Germany, France, Great Britain and Portugal. However, they have only a few members, many of whom are Japanese students or employees or of Brazilian origin (Clarke 2000:290-93).

with Sōka Gakkai it is also the largest Japanese new religion outside of Japan. Missionary activities in Brazil began in the mid-1950s when members immigrating to Brazil transmitted their faith to fellow Japanese immigrants. After Taniguchi’s visit to Brazil in 1963, however, missionary efforts turned to non-Japanese as well. Recently, Seichō no Ie’s membership in Brazil (the Brazilian headquarters are Seichō no Ie’s missionary headquarters for all of Latin America) has been estimated at around half a million members, eighty to ninety per cent of whom have no Japanese ancestry ( Carpenter and Roof 1995; Maeyama 1992; Shimazono 1991 ). Although missions to Hawai’i and other parts of the United States began before the Pacific War, membership figures do not compare to those in Brazil and most members are of Japanese descent. There are Seichō no Ie branches in several European countries, such as Germany, France, Great Britain and Portugal. However, they have only a few members, many of whom are Japanese students or employees or of Brazilian origin (Clarke 2000:290-93). (Taniguchi M. and J. 2010 and Seichō no Ie online e ). The main temple in Nagasaki primarily serves ceremonial functions and contains the main shrine dedicated to Sumiyoshi Daijin, a Shintō deity said to “protect the state and purify the universe” ( Shūkyō Hōjin Seichō no Ie Sōhonzan online d) . The third religious center is the Additional Main Temple in Uji, near Kyoto, which focuses on the veneration of members’ ancestors and the care for stillborn or aborted babies. Hence it includes the main ancestral shrine (Fieldwork Observations; and Seichō no Ie Uji Bekkaku Honzan online a) . Additionally, Seichō no Ie has 129 hierarchically structured regional and local branches in Japan ( Seich<o no Ie online d ). It runs its own publishing company, Nihon Kyōbunsha, and a young women’s boarding school ( Seichō no Ie Yōshin Joshi Gakuen), whose educational focus lies on Seichō no Ie’s scriptures, on housewifely skills such as childcare and nutrition, on artistic courses such as music and traditional Japanese arts, and on basic office skills ( Seichō no Ie Yōshin Joshi Gakuen online ).

(Taniguchi M. and J. 2010 and Seichō no Ie online e ). The main temple in Nagasaki primarily serves ceremonial functions and contains the main shrine dedicated to Sumiyoshi Daijin, a Shintō deity said to “protect the state and purify the universe” ( Shūkyō Hōjin Seichō no Ie Sōhonzan online d) . The third religious center is the Additional Main Temple in Uji, near Kyoto, which focuses on the veneration of members’ ancestors and the care for stillborn or aborted babies. Hence it includes the main ancestral shrine (Fieldwork Observations; and Seichō no Ie Uji Bekkaku Honzan online a) . Additionally, Seichō no Ie has 129 hierarchically structured regional and local branches in Japan ( Seich<o no Ie online d ). It runs its own publishing company, Nihon Kyōbunsha, and a young women’s boarding school ( Seichō no Ie Yōshin Joshi Gakuen), whose educational focus lies on Seichō no Ie’s scriptures, on housewifely skills such as childcare and nutrition, on artistic courses such as music and traditional Japanese arts, and on basic office skills ( Seichō no Ie Yōshin Joshi Gakuen online ). volume of his collected essays, System of Value-Creating Educational Study ( Sōka kyōikugaku taikei ), marking the start of the Value Creation Education Study Association (Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai), Sōka Gakkai’s predecessor. Makiguchi was born in 1871 in what is now Niigata Prefecture in northeastern Japan, but he moved to the northern island of Hokkaido at the age of thirteen, where he was raised and eventually educated as an elementary school teacher. In 1901, he moved with his wife and children from the Hokkaido city of Sapporo to Tokyo, where he embarked on a career teaching at a series of Tokyo elementary schools. He also collaborated with intellectuals concerned with educational reform as he published books and essays. From 1910, Makiguchi joined the Kyōdokai, or Home Town Association, a research group engaged in ethnology and surveys of local culture in rural areas; the group included the famed folklorist Yanagita Kunio (1875-1962) and internationally renowned educator Nitobe Inazō (1862-1933). Thanks to scholarly engagements in these circles and through his own research, Makiguchi’s ideas were influenced by educational and philosophical trends, including neo-Kantian thought and pragmatism, which moved from Europe and the United States into Japan around the turn of the twentieth century.

volume of his collected essays, System of Value-Creating Educational Study ( Sōka kyōikugaku taikei ), marking the start of the Value Creation Education Study Association (Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai), Sōka Gakkai’s predecessor. Makiguchi was born in 1871 in what is now Niigata Prefecture in northeastern Japan, but he moved to the northern island of Hokkaido at the age of thirteen, where he was raised and eventually educated as an elementary school teacher. In 1901, he moved with his wife and children from the Hokkaido city of Sapporo to Tokyo, where he embarked on a career teaching at a series of Tokyo elementary schools. He also collaborated with intellectuals concerned with educational reform as he published books and essays. From 1910, Makiguchi joined the Kyōdokai, or Home Town Association, a research group engaged in ethnology and surveys of local culture in rural areas; the group included the famed folklorist Yanagita Kunio (1875-1962) and internationally renowned educator Nitobe Inazō (1862-1933). Thanks to scholarly engagements in these circles and through his own research, Makiguchi’s ideas were influenced by educational and philosophical trends, including neo-Kantian thought and pragmatism, which moved from Europe and the United States into Japan around the turn of the twentieth century. and made his way to the imperial capital to pursue his fortunes in teaching. Even after he left the teaching profession in late 1922, Toda remained beholden to his mentor Makiguchi, and he attributed his subsequent success in business to Makiguchi’s teachings. Toda alone demonstrated absolute commitment to Makiguchi by refusing to bow to the Japanese state’s pressure to recant his Nichiren Shōshū beliefs. While in prison, Toda experienced a vision in which he joined the innumerable Bodhisattvas of the Earth ( jiyu no bosatsu ) at Vulture Peak where the Buddha Śākyamuni delivers the Lotus Sūtra . He interpreted this revelation as an awakening to the sacred task of continuing his master Makiguchi’s mission to propagate Nichiren Shōshū Buddhism.

and made his way to the imperial capital to pursue his fortunes in teaching. Even after he left the teaching profession in late 1922, Toda remained beholden to his mentor Makiguchi, and he attributed his subsequent success in business to Makiguchi’s teachings. Toda alone demonstrated absolute commitment to Makiguchi by refusing to bow to the Japanese state’s pressure to recant his Nichiren Shōshū beliefs. While in prison, Toda experienced a vision in which he joined the innumerable Bodhisattvas of the Earth ( jiyu no bosatsu ) at Vulture Peak where the Buddha Śākyamuni delivers the Lotus Sūtra . He interpreted this revelation as an awakening to the sacred task of continuing his master Makiguchi’s mission to propagate Nichiren Shōshū Buddhism. from a Japan-focused lay Buddhist organization into an international enterprise with a broad mandate in religion, politics, and culture. Under Ikeda’s leadership, Sōka Gakkai established official branches in Asia, Europe, North America, Brazil, and other parts of the globe. Under Ikeda, Sōka Gakkai founded its own accredited private school system, sub-organizations committed to supporting the arts, and other education- and culture-focused initiatives.

from a Japan-focused lay Buddhist organization into an international enterprise with a broad mandate in religion, politics, and culture. Under Ikeda’s leadership, Sōka Gakkai established official branches in Asia, Europe, North America, Brazil, and other parts of the globe. Under Ikeda, Sōka Gakkai founded its own accredited private school system, sub-organizations committed to supporting the arts, and other education- and culture-focused initiatives. facility at the Nichiren Shōshū head temple Taisekiji to house the daigohonzon , the calligraphic mandala inscribed by Nichiren in 1279 that serves Sōka Gakkai and Nichiren Shōshū as their primary object of worship. The Shōhondō was referred to until the end of the decade by Shōshū and Gakkai leaders as a virtual realization of the “true ordination platform” (the honmon no kaidan), marking the completed task of converting the populace.

facility at the Nichiren Shōshū head temple Taisekiji to house the daigohonzon , the calligraphic mandala inscribed by Nichiren in 1279 that serves Sōka Gakkai and Nichiren Shōshū as their primary object of worship. The Shōhondō was referred to until the end of the decade by Shōshū and Gakkai leaders as a virtual realization of the “true ordination platform” (the honmon no kaidan), marking the completed task of converting the populace. and a new Gakkai policy of “separation of politics and religion” (seikyō bunri ). The official separation of the religion and the political party served as a watershed moment for both organizations: Sōka Gakkai’s membership only grew by small amounts after this, and Kōmeitō suffered electoral losses throughout the following decade. Even after the official separation, devout Gakkai adherents have continued to regard electioneering on behalf of Kōmeitō candidates as part of their regular faith activities.

and a new Gakkai policy of “separation of politics and religion” (seikyō bunri ). The official separation of the religion and the political party served as a watershed moment for both organizations: Sōka Gakkai’s membership only grew by small amounts after this, and Kōmeitō suffered electoral losses throughout the following decade. Even after the official separation, devout Gakkai adherents have continued to regard electioneering on behalf of Kōmeitō candidates as part of their regular faith activities. Nichiren as the earthly avatar of the eternal or original Buddha. As such, his writings are considered by Gakkai followers to bear scriptural authority surpassing even that of the sūtra s of the Buddha Śākyamuni.

Nichiren as the earthly avatar of the eternal or original Buddha. As such, his writings are considered by Gakkai followers to bear scriptural authority surpassing even that of the sūtra s of the Buddha Śākyamuni. engage in numerous other activities that make up ritual life in the group. These include:

engage in numerous other activities that make up ritual life in the group. These include: service. Honorary President Ikeda floats above a massive pyramidal structure topped by a president (currently sixth president Harada Minoru) who oversees more than five hundred vice-presidents, a board of regents, and many other paid administrators who in turn oversee the activities of the Gakkai’s many subdivisions. Members are grouped by age, marital status, gender, location, occupation, and many other demographic considerations. The primary sub-organizations are the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Divisions, the Married Women’s Division, and the Men’s Division. Children under the age of eighteen belong to the Future Division. Members across Japan belong to a vertical administrative hierarchy based in households (setai) that are organized into blocks (burokku), districts (chiku), chapters (shibu), regional headquarters (honbu), wards (ku or ken), and prefectures (ken), which are in turn administered by thirteen national districts; almost all of the administrative work ensuring the daily operation of these subdivisions is carried out by volunteer administrators. One active member may hold multiple volunteer administrative posts at different levels of the organization, from the block on upward, and each of these positions will entail numerous responsibilities. The most active members at the local level belong to the Married Women’s Division, and though the majority of regular attendees at meetings are women, membership in Sōka Gakkai’s administration, with the exception of the Future, Young Women’s, and Married Women’s Divisions, is restricted to men.

service. Honorary President Ikeda floats above a massive pyramidal structure topped by a president (currently sixth president Harada Minoru) who oversees more than five hundred vice-presidents, a board of regents, and many other paid administrators who in turn oversee the activities of the Gakkai’s many subdivisions. Members are grouped by age, marital status, gender, location, occupation, and many other demographic considerations. The primary sub-organizations are the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Divisions, the Married Women’s Division, and the Men’s Division. Children under the age of eighteen belong to the Future Division. Members across Japan belong to a vertical administrative hierarchy based in households (setai) that are organized into blocks (burokku), districts (chiku), chapters (shibu), regional headquarters (honbu), wards (ku or ken), and prefectures (ken), which are in turn administered by thirteen national districts; almost all of the administrative work ensuring the daily operation of these subdivisions is carried out by volunteer administrators. One active member may hold multiple volunteer administrative posts at different levels of the organization, from the block on upward, and each of these positions will entail numerous responsibilities. The most active members at the local level belong to the Married Women’s Division, and though the majority of regular attendees at meetings are women, membership in Sōka Gakkai’s administration, with the exception of the Future, Young Women’s, and Married Women’s Divisions, is restricted to men. drawn at the center. Gakkai territory is instantly recognizable in Japan when the flag hangs over a building, a member’s home, or a business run by an adherent.

drawn at the center. Gakkai territory is instantly recognizable in Japan when the flag hangs over a building, a member’s home, or a business run by an adherent. Heikichi (島田平吉), the older brother of the founder Shimada Seiichi (島田晴一). [Image at right] In January of 1895 Shimada received a message from Tenshin Ōmikami announcing that a younger brother would be born the following year, and he was to be named Seiichi. He also received a schoolbag and shoes of high quality, which he said were gifts from the deity to be used by Seiichi when he was born. Throughout the year prior to Seiichi’s birth, Heikichi did miracle working in the name of Tenshin Ōmikami. Then in 1896, the official founder of the religion, Shimada Seiichi, was born. He is referred to as “Shodai-sama” (初代様, First Master) by followers.

Heikichi (島田平吉), the older brother of the founder Shimada Seiichi (島田晴一). [Image at right] In January of 1895 Shimada received a message from Tenshin Ōmikami announcing that a younger brother would be born the following year, and he was to be named Seiichi. He also received a schoolbag and shoes of high quality, which he said were gifts from the deity to be used by Seiichi when he was born. Throughout the year prior to Seiichi’s birth, Heikichi did miracle working in the name of Tenshin Ōmikami. Then in 1896, the official founder of the religion, Shimada Seiichi, was born. He is referred to as “Shodai-sama” (初代様, First Master) by followers. In response, Seiichi officially registered the religion as Tenshin Ōmikamikyō in 1952. From the 1960s to the 1970s the religion continued to grow and its activities expanded. In 1960, the Tokyo temple (Image at right) was completed, mostly through donations from members. Following this, in 1961 Seiichi received divine instruction from Tenshin Ōmikami in how to perform a healing method involving injections of “divine water” (go-shinsui) to cure a range of illnesses. In 1967, their healing facility, Yamatoura Clinic, officially opened; it was later renamed Tenshin Clinic.

In response, Seiichi officially registered the religion as Tenshin Ōmikamikyō in 1952. From the 1960s to the 1970s the religion continued to grow and its activities expanded. In 1960, the Tokyo temple (Image at right) was completed, mostly through donations from members. Following this, in 1961 Seiichi received divine instruction from Tenshin Ōmikami in how to perform a healing method involving injections of “divine water” (go-shinsui) to cure a range of illnesses. In 1967, their healing facility, Yamatoura Clinic, officially opened; it was later renamed Tenshin Clinic. generic term for god, kami-sama (神様). Members note they are monotheistic, worship only Tenshin Ōmikami, and do not worship any other gods or intermediaries. Moreover, they do not see their leaders or the founder as being divine, but rather as messengers of Tenshin Ōmikami. They note that Tenshin Ōmikami has descended to Earth through human forms on three occasions, first as Moses, second as Jesus, and third as Heikichi and Seiichi (which is seen as one instance). Tenshinseiky ō is thus seen as being part of the same lineage of all world religions, though it does not posit any particular genealogical progression in terms of religious teachings or revelations. Some members also note that while they believe that Tenshinseikyō is the “right” (tadashii) religion for them, other religions may be “right” for other people, and that ultimately all religions have the same roots. Thus, members generally do not express feelings of competition or animosity with other religious groups or beliefs.