Toronto Blessing

THE TORONTO BLESSING (Catch the Fire)

TORONTO BLESSING TIMELINE:

1977: John Wimber established a Calvary Chapel in Yorba Linda, California.

1980: Lonnie Frisbee shared testimony in a turning point for Wimber’s church.

1981: John and Carol Arnott entered full-time ministry and established Jubilee Christian Fellowship in Stratford, Ontario.

1982: Wimber affiliated with Ken Gullikson’s The Vineyard in Southern California ; Gullikson ceded leadership to Wimber.

1984: Wimber established the Association of Vineyard Churches, a network that grew to include some 500 congregations within the next ten years.

1985: John Arnott attended a Wimber “Signs and Wonders” Conference in Vancouver, Canada.

1987: Arnott joined the Association of Vineyard Churches.

1988: Arnott established a “kinship group” in Toronto that would become the Toronto Airport Vineyard (TAV), growing to 350 people by 1994.

1990: Jerry Steingard introduced Arnott to the prophet Marc Dupont.

1991: Marc Dupont urged the Arnotts to leave Stratford and move to Toronto “in order to prepare for what God had in store for them.”

1991 (May): Marc Dupont moved to Torontox to assume a part-time position at TAV.

1993: John and Carol Arnott traveled to Argentina in November where a large revival was taking place.

1994 (January 20): Randy Clark, Vineyard pastor from Missouri , was invited to preach a three-day revival at TAV, launching a global revival known as the “Toronto Blessing.”

1994 (April): The revival began to attract international news as it manifested in churches in the U.K.

1994 (June): Wimber visited TAV and related what he observed to the turning point he experienced with the ministry of Lonnie Frisbee in 1990.

1995: The Toronto Blessing became a global phenomenon, and visitors came to the nightly gatherings from all over the world. By the first anniversary celebration, TAV purchased the former Asian Trade Center to accommodate the crowds.

1995: Major epicenters of revival with nightly meetings developed in places like Melbourne, Florida and Pasadena, California. Visits by Bill Johnson (Redding, California ) and Brenda Kilpatrick (Pensacola, Florida) served as sparks for other revival ministries, including a revival at Johnson’s Bethel Assembly of God in Redding, California and Brownsville Assembly of God Church pastored by John Kilpatrick in Florida .

1995: The Toronto Airport School of Ministry (now known as Catch the Fire College) was founded.

1995 (December): TAV was dismissed from Wimber’s Association of Vineyard Churches; its name was soon changed to the Toronto Airport Christian Fellowship (TACF).

1996: The Canadian Arctic Outpouring broke out in various communities in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, in the eastern Canadian Arctic.

1996: John Arnott established Partners in Harvest and Friends in Harvest, inviting revival churches throughout the globe into a “new family network” of churches.

1996: Rolland and Heidi Baker, missionaries to Mozambique and founders of Iris Ministries, visited TACF.

1999: Gold fillings and golden flakes were reported at TACF; the phenomenon spread quickly to other revival churches.

2003: Soaking Prayer Centers developed around the world; launching of the International Leadership Schools.

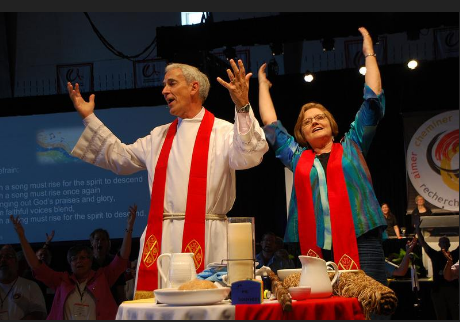

2006 (January 22): John and Carol Arnott commissioned Steve and Sandra Long as the new senior pastors of the Toronto Airport Christian Fellowship.

2006: After twelve years, the protracted nightly (except for Mondays) renewal meetings at TACF end were discontinued.

2008: Duncan and Kate Smith moved to Raleigh , North Carolina to plant the first Catch the Fire Church .

2010: Toronto Airport Christian Fellowship (TACF) became a Catch the Fire (CTF).

2014 (January 24): The Twentieth Anniversary Celebration was held with Randy Clark and the Arnotts as speakers.

2014 (January 21-24): The Revival Alliance Conference was held in Toronto with Revival Alliance associates Randy Clark, Heidi Baker, Bill Johnson, Che Ahn, and Georgian Banov joining the Arnotts as speakers.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Like the larger Pentecostal network of which it is a part, the Toronto Blessing is first and foremost a religious experience, specifically experiential manifestations held to be the manifest presence and power of God. Not long after its inception in 1994, Philip Richter defined the Blessing as follows: “ The ‘Toronto Blessing’ is a form of religious experience characterized by many unusual physical phenomena – such as bodily weakness and falling to the ground; shaking, trembling and convulsive bodily movements; uncontrollable laughter or wailing and inconsolable weeping; apparent drunkenness; animal sounds; and intense physical activity . . . . as well as being accompanied by such things as a heightened sense of the presence of God; ‘prophetic’ insights into the future; ‘prophetic’ announcements from God; visions; and ‘out of the body’ mystical experiences (Richter 1997:97).

Pentecostalism, both in its historic and more recent neo-pentecostal forms, has long been regarded as comprised of “reticulate and weblike” organizations characterized and energized by ongoing religious experience (c.f. Gerlach and Hine 1970; Poloma 1982). Perhaps nothing reflects its amorphous form better than the countless pentecostal revivals that have sprung up within  nations, regions or in local churches over the past century. The Toronto Blessing is arguably the best-known North American revival since the early twentieth century Azusa Street Revival, commonly considered to be the birthplace of American pentecostalism. What happened in a small mission on Azusa Street in Los Angeles , California from 1906-1909 has proved to be an important catalyst, if not the most important catalyst, that launched the global Pentecostal Movement (Anderson 2004; Robeck 2006).

nations, regions or in local churches over the past century. The Toronto Blessing is arguably the best-known North American revival since the early twentieth century Azusa Street Revival, commonly considered to be the birthplace of American pentecostalism. What happened in a small mission on Azusa Street in Los Angeles , California from 1906-1909 has proved to be an important catalyst, if not the most important catalyst, that launched the global Pentecostal Movement (Anderson 2004; Robeck 2006).

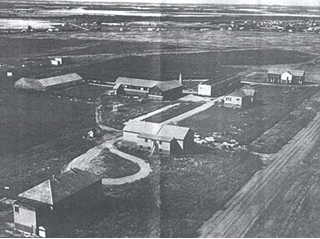

“Catch the Fire,” as the network originating in the Toronto Blessing has come to be known, is rooted in a revival that began on January 20, 1994 at the Toronto Airport Vineyard (TAV), a congregation located in a leased unit of an industrial mall on Dixie Road just west of the Pearson International Airport. By late 1994 as thousands of visitors poured into the church from all parts of the globe, TAV relocated to its present nearby location at 272 Attwell Drive, first renting and then purchasing the building that  seated three thousand and had once housed the Asian Trade Center. With international access readily available by air, the Internet and the emerging World Wide Web, religious seekers would come from all continents (save for Antarctica )! Its story includes many adoptions and adaptations during its twenty year history as it sparked new and refreshed old revival fires. It continues to play a significant role (directly and indirectly) in reviving and expanding streams of pentecostalism found in the Americas and across the globe.

seated three thousand and had once housed the Asian Trade Center. With international access readily available by air, the Internet and the emerging World Wide Web, religious seekers would come from all continents (save for Antarctica )! Its story includes many adoptions and adaptations during its twenty year history as it sparked new and refreshed old revival fires. It continues to play a significant role (directly and indirectly) in reviving and expanding streams of pentecostalism found in the Americas and across the globe.

Pentecostal revivals have been likened to wildfire, and as with many large fires, it is often difficult to identify a single igniting spark. Many commonly claim the Azusa Street Mission as the historic site that torched the ”first wave” of pentecostalism that led to the formation of the historical or classical Pentecostal denominations, including the Church of God in Christ, the Assemblies of God, and the Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada. A “second wave”, the Charismatic Movement, was rooted in a healing revival (c.f., Kathryn Kuhlman and Oral Roberts) of the late 1940s and 1950s. The Charismatic Movement introduced common pentecostal experiences (divine healing, tongues, prophecy) to mainline Protestant, Catholic and Orthodox denominations and the founding of charismatic non-denominational churches. Gathering strength and reaching its peak during the decades of the 1960s and 70s, the second wave was fueled by parachurch healing revivalists and parachurch groups (most notably the Full Gospel Business Men’s Fellowship International), but denounced by most established Pentecostal sects and denominations. It was said to have crested at the Kansas City Conference of 1977. By the early 1980s it became apparent that the two major waves of North American pentecostalism might be in need of more renewal and refreshing (Poloma 1982).

The beginning of a “third wave” is commonly marked by the spiritual transformation and ministry of John Wimber, an unchurched  saxophone player for the 1960s popular rock band, The Righteous Brothers. Wimber would become a Christian believer in the mid-1960s and affiliated with the Yorba Linda Friends Church in southern California. He was “recorded” (“ordained” in the evangelical Quaker tradition), served as a co-pastor, and began small group with a focus on worship and prayer (that grew to 100 people). Tension would develop between Wimber’s “small group” and Yorba Linda Friends Church , and Wimber would leave the Quakers to focus on his new congregation. In 1977, Wimber associated his church with Chuck Smith’s Calvary network. Smith (although raised Pentecostal had moved away from its experiential theology) welcomed hippies into his congregation that became the “mother church” of the Calvary movement (Miller 1997). Acceptance of young converts from the controversial “Jesus People Movement” of the 1970s was atypical for evangelical church leaders of the time, but hippies grooving on Jesus rather than drugs was something with which Wimber easily resonated.

saxophone player for the 1960s popular rock band, The Righteous Brothers. Wimber would become a Christian believer in the mid-1960s and affiliated with the Yorba Linda Friends Church in southern California. He was “recorded” (“ordained” in the evangelical Quaker tradition), served as a co-pastor, and began small group with a focus on worship and prayer (that grew to 100 people). Tension would develop between Wimber’s “small group” and Yorba Linda Friends Church , and Wimber would leave the Quakers to focus on his new congregation. In 1977, Wimber associated his church with Chuck Smith’s Calvary network. Smith (although raised Pentecostal had moved away from its experiential theology) welcomed hippies into his congregation that became the “mother church” of the Calvary movement (Miller 1997). Acceptance of young converts from the controversial “Jesus People Movement” of the 1970s was atypical for evangelical church leaders of the time, but hippies grooving on Jesus rather than drugs was something with which Wimber easily resonated.

The significant turning point in Wimber’s ministry that would lead him away from the Calvary movement occurred on Mother’s Day in 1980. “The stuff,” (as Wimber would call unusual spiritual experiences described by Richter in the opening paragraph)  erupted unexpectedly in his church. Wimber had invited Lonnie Frisbee, a young hippie who had been a key figure in the Jesus People Movement, to give his testimony (Frisbee with Sachs 2012). An unexpected outbreak of strange physical manifestations, including the speaking in tongues, occurred in the Mother’s Day service, leaving Wimber nonplused and seeking divine guidance. In response to a prayer asking God if the seeming pandemonium that swept through the congregation was of divine origin, a minister friend from Colorado (unaware of what had transpired at Wimber’s church that morning) phoned saying that he had been divinely instructed to call and to tell Wimber “It was Me.” Wimber would soon abandon Smith’s cessationist theology that discounted the paranormal “gifts of the Spirit” (e.g. speaking in tongues, healing, prophecies and miracles) as practiced in Pentecostalism (Jackson 1999). Once again Wimber would find himself in tension with a religious mentor.

erupted unexpectedly in his church. Wimber had invited Lonnie Frisbee, a young hippie who had been a key figure in the Jesus People Movement, to give his testimony (Frisbee with Sachs 2012). An unexpected outbreak of strange physical manifestations, including the speaking in tongues, occurred in the Mother’s Day service, leaving Wimber nonplused and seeking divine guidance. In response to a prayer asking God if the seeming pandemonium that swept through the congregation was of divine origin, a minister friend from Colorado (unaware of what had transpired at Wimber’s church that morning) phoned saying that he had been divinely instructed to call and to tell Wimber “It was Me.” Wimber would soon abandon Smith’s cessationist theology that discounted the paranormal “gifts of the Spirit” (e.g. speaking in tongues, healing, prophecies and miracles) as practiced in Pentecostalism (Jackson 1999). Once again Wimber would find himself in tension with a religious mentor.

In 1982, Wimber withdrew his alliance with Chuck Smith’s Calvary Chapel network and with Smith’s encouragement affiliated with Ken Gulliksen, a minister who held beliefs similar to Wimber’s on the experience of the gifts of the Spirit and who had recently established a church under the Vineyard name (Jackson 1999; DiSabatino 2006). Within a year  Gulliksen would give the leadership of the Vineyard Church to Wimber, and 1984, Wimber established the Association of Vineyard Churches (AVC), a network of churches. The AVC grew to include some 500 congregations spread throughout North America and in the United Kingdom within the next ten years. Wimber promoted the gifts of the spirit as “power evangelism,” where “the stuff” of supernatural happenings (especially divine healing) was affirmed as a propelling force for modern evangelism (Wimber and Springer 1986). The AVC became a primary marker for what Fuller Theological Seminary professor C. Peter Wagner called the “third wave” of the growing Pentecostal Movement in America . Many of these same spiritual phenomena experienced in Vineyard churches under Wimber’s ministry would later happen nightly at TAV/TACF.

Gulliksen would give the leadership of the Vineyard Church to Wimber, and 1984, Wimber established the Association of Vineyard Churches (AVC), a network of churches. The AVC grew to include some 500 congregations spread throughout North America and in the United Kingdom within the next ten years. Wimber promoted the gifts of the spirit as “power evangelism,” where “the stuff” of supernatural happenings (especially divine healing) was affirmed as a propelling force for modern evangelism (Wimber and Springer 1986). The AVC became a primary marker for what Fuller Theological Seminary professor C. Peter Wagner called the “third wave” of the growing Pentecostal Movement in America . Many of these same spiritual phenomena experienced in Vineyard churches under Wimber’s ministry would later happen nightly at TAV/TACF.

In 1981, about the time that Wimber was transitioning from Calvary Chapel to the Vineyard, John Arnott put aside his successful  travel business to establish his first church, Jubilee Christian Fellowship, an independent congregation in Stratford, Ontario. Four years later Arnott met Wimber at “Signs and Wonders” Conference held in Vancouver, B.C. at which Wimber was a main speaker. In 1987, with the encouragement of Gary Best and his team from the Langley Vineyard in British Columbia, John and Carol Arnott together with their church joined the AVC. While living in Stratford in 1988, John and Carol had been making regular trips to Toronto where they began a “cell church” that met in the home of John’s mother. That ministry would become the Toronto Airport Vineyard (TAV). When the revival began in January, 1994, TAV was a congregation of a reported 350 people, including children (Steingard with Arnott 2014).

travel business to establish his first church, Jubilee Christian Fellowship, an independent congregation in Stratford, Ontario. Four years later Arnott met Wimber at “Signs and Wonders” Conference held in Vancouver, B.C. at which Wimber was a main speaker. In 1987, with the encouragement of Gary Best and his team from the Langley Vineyard in British Columbia, John and Carol Arnott together with their church joined the AVC. While living in Stratford in 1988, John and Carol had been making regular trips to Toronto where they began a “cell church” that met in the home of John’s mother. That ministry would become the Toronto Airport Vineyard (TAV). When the revival began in January, 1994, TAV was a congregation of a reported 350 people, including children (Steingard with Arnott 2014).

In November of 1993, John and Carol Arnott made a pilgrimage to a pastors and leaders conference in Buenos Aires, Argentina . Claudio Freidzon, a local Assemblies of God evangelist and leader of a revival in process in Argentina asked John “Do you want the anointing?” When John responded affirmatively, Claudio said “Then take it.” John would later report “something clicking in my heart” during which he received “the anointing and power by faith.” On the return trip to Toronto , the Arnotts made a stop at a Vineyard church in southern California where they first learned about Randy Clark’s dramatic experiences with the supernatural. Within two months the seemingly same power that Arnott saw and prayed for in Argentina would come to TAV through Clark ‘s ministry (Arnott 1995).

Impacted by the famous healing ministry of evangelist Kathryn Kuhlman, as well as a friendship with evangelist and faith healer Benny Hinn since the 1970s, Carol and John Arnott were hardly strangers to the “second wave” of pentecostalism. But it was John Wimber and the AVC who would have the greatest impact on the Arnotts’ ministry. The AVC network provided a steady stream of “third wave” leaders who helped to lay the foundation for the Toronto Blessing. In 1990, Jerry Steingard, who became pastor of the church in Stratford when the Arnotts moved to Toronto, introduced Arnott to Marc Dupont, one of the emerging third wave prophets. In 1991, Dupont would prophetically urge the Arnotts to leave Stratford and move to Toronto “in order to prepare for what God had in store for them” (Steingard with Arnott 2014). Later that year Dupont and his family moved to Toronto from San Diego , where he took a part-time position at TAV. (Dupont became a prophetic voice for revival with his predictions that spiritual renewal and refreshing was soon to come to Toronto .) The AVC also would provide the network through which Arnott would hear about the revival experience of Randy Clark, a Vineyard pastor from Missouri who reportedly had developed a gift for imparting revival experiences to congregations and whose ministry at TAV sparked the Toronto Blessing.

Clark first witnessed Wimber’s ministry when he attended conference in Dallas in January 1984. Clark reports, “I saw firsthand the  power of God affecting people physically and causing them to tremble and/or fall down.” During that conference Wimber prophesied blessings over Clark’s life that included a word that he is “a Prince in the Kingdom of God ” (Johnson and Clark 2011:25). Clark would later learn that “John [Wimber] had heard God tell him audibly that I would one day go around the world laying hands on pastors and leaders to impart and stir up the spiritual gifts in them” (Johnson and Clark 2011:25). But in August, 1993 this former Baptist now pastor of an AVC church in St. Louis, Missouri claimed to be “burned-out” and close to a nervous breakdown after years of tough but seemingly unfruitful ministry. Nearly at wits end, Clark reluctantly and skeptically went to Tulsa, Oklahoma where Rodney Howard-Browne, an immigrant evangelist from South Africa who was at the center of the so-called “laughing revival,” was speaking. Clark found both his heaviness and skepticism lift during this revival meeting when he wound up on the floor laughing for no apparent reason. He soon attended another Howard-Browne meeting in Lakeland , Florida when Clark felt a tremendous power come into his hands as Howard-Browne” said to him: “This is the fire of God in your hands—go home and pray for everybody in your church.” Clark did as instructed and reportedly 95 percent of the congregation fell on the floor “under the power” (Poloma 2003:156).

power of God affecting people physically and causing them to tremble and/or fall down.” During that conference Wimber prophesied blessings over Clark’s life that included a word that he is “a Prince in the Kingdom of God ” (Johnson and Clark 2011:25). Clark would later learn that “John [Wimber] had heard God tell him audibly that I would one day go around the world laying hands on pastors and leaders to impart and stir up the spiritual gifts in them” (Johnson and Clark 2011:25). But in August, 1993 this former Baptist now pastor of an AVC church in St. Louis, Missouri claimed to be “burned-out” and close to a nervous breakdown after years of tough but seemingly unfruitful ministry. Nearly at wits end, Clark reluctantly and skeptically went to Tulsa, Oklahoma where Rodney Howard-Browne, an immigrant evangelist from South Africa who was at the center of the so-called “laughing revival,” was speaking. Clark found both his heaviness and skepticism lift during this revival meeting when he wound up on the floor laughing for no apparent reason. He soon attended another Howard-Browne meeting in Lakeland , Florida when Clark felt a tremendous power come into his hands as Howard-Browne” said to him: “This is the fire of God in your hands—go home and pray for everybody in your church.” Clark did as instructed and reportedly 95 percent of the congregation fell on the floor “under the power” (Poloma 2003:156).

Randy Clark accepted John Arnott’s invitation to minister a four-day conference at the TAV on January 20, 1994. On the first day, the unexpected happened to the approximately 120 persons gathered. As Arnott (1998:5) reports: “It hadn’t occurred to us that God would throw a massive party where people would laugh, roll, cry, and become so empowered that emotional hurts from childhood would just lift off. Some people were so overcome physically by God’s power that they had to be carried out.” Amazed that the revival phenomena continued daily, Clark gradually extended his stay at TAV for nearly two months, spending forty-two of the next sixty days in Toronto (Steingard with Arnott 2014). The nightly protracted meetings would continue with or without Clark or Arnott present over the weeks, months and years that followed, as thousands of pilgrims came from around the world seeking what Arnott prefers to call the “Father’s Blessing.”

By April, 1994, the revival had spread to churches in the United Kingdom. It would to go viral in May when Eleanor Mumford, wife of an AVC pastor in Southwest London , gave a testimony of her TAV experiences at an affluent Anglican church, Holy Trinity Brompton (HTB). The revival that followed at HTB attracted the attention of the British press that was quick to break the story of what they dubbed the “Toronto Blessing” (Roberts 1994; Hilborn 2001).

John Wimber did not visit TAV until June, 1994, and he reportedly distanced himself from the party-like atmosphere of the revival. The revival continued to attract crowds coming from around the world with many pilgrims standing in line for hours trying to gain entrance to the main room of the industrial building that held 300 people (with another 300 watching on screen in the overflow). By its first anniversary celebration in January, 1995, TAV had relocated to nearby Attwell Drive to accommodate the thousands of visitors now coming to the nightly services and special conferences from around the world. But all was not well with the relationship between John Wimber and John Arnott. In December of 1995, Wimber would visit TAV, saying he had not come to discuss but to announce that the TAV would no longer be a part of the AVC. By the second anniversary celebration in January, 1996, the Toronto Airport Vineyard would be known as the Toronto Airport Christian Fellowship (TACF).

During its heyday in the 1990s, the revival at TACF drew thousands of pilgrims nightly from twenty or more different countries (not uncommonly arriving in large chartered planes), many of whom would carry the Blessing back to their home churches where local revivals broke out. There were countless revival hotspots of various intensities and durations that erupted in congregations throughout North America . Some of them would host revival meetings for months or years, including well-known ones that persist with periodic revival conferences in Pasadena , California (HRock, formerly “ Harvest Rock Church ) and in Redding , California (Bethel Redding, formerly Bethel Assemblies of God, Redding ). Both HRock and Bethel together with Catch the Fire (as TACF is now known) are active in the “Revival Alliance” formed by John Arnott, Randy Clark, and other revival leaders. In 2006, after hosting revival meetings for twelve years, TACF would discontinue its nightly gatherings that once drew thousands from around the globe.

In 2010, TACF would become known as Catch the Fire (CTF), distinguishing emergent and emerging churches in other locations  from the mother church on Attwell Drive in Toronto . On January 24, 2014, CTF hosted a simple Twentieth Anniversary Celebration Night with John Arnott and Randy Clark as speakers: “20 Years Ago on January 20 th 1994, God blessed our small church at the end of the runway in Toronto with an outpouring of the Holy Spirit. Since then God has transformed so many people’s lives all over the world!” (“Twentieth Anniversary Celebration” 2014). A related conference followed during the next three days and nights under the auspices of the Revival Alliance.

from the mother church on Attwell Drive in Toronto . On January 24, 2014, CTF hosted a simple Twentieth Anniversary Celebration Night with John Arnott and Randy Clark as speakers: “20 Years Ago on January 20 th 1994, God blessed our small church at the end of the runway in Toronto with an outpouring of the Holy Spirit. Since then God has transformed so many people’s lives all over the world!” (“Twentieth Anniversary Celebration” 2014). A related conference followed during the next three days and nights under the auspices of the Revival Alliance.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

“Toronto Blessing” beliefs are rooted in worldview that can best be described as postmodern, providing a lens for viewing everyday reality that includes metaphysical experiences and events. This alternative worldview can be likened to living in a world of possibilities, where the “as is” of commonly shared empirical reality and the “as if” of metaphysical experiences (not unlike those reported throughout the Bible) dance together. In this the Toronto Blessing shares the miracles, mysteries, and magic found in the first wave of historic Pentecostalism that includes experiences to the non-modern world of spirits, especially the Holy Spirit. But third-wavers differ from their Pentecostal spiritual fathers and mothers who rejected modern culture, including higher education, science, sports, cosmetics and jewelry — even public beaches and pools where men and women would swim together. Third-wavers are more likely to adopt and adapt contemporary culture for their own ends, as John Wimber did when he embraced hippie converts to the movement. Like the Pentecostals of old, however, third-wavers commonly report encounters with the divine as well as with angels and demons, insisting that seemingly supernatural events are in fact normal Christian living. They tend to see the world and to interpret its events through different lenses than their fundamentalist and many of their evangelical cousins with whom they are often confused.

In his study of “reinventing American Protestantism,” Miller (1997:121-22) has noted that “new paradigm churches [like the  Association of Vineyard Churches] . . . do not fit the traditional categories.” Their perspective differs from both Christian conservatives and liberals. Miller calls them as “doctrinal minimalists” and “cultural innovators,” and provides the following succinct description in support of his thesis:

Association of Vineyard Churches] . . . do not fit the traditional categories.” Their perspective differs from both Christian conservatives and liberals. Miller calls them as “doctrinal minimalists” and “cultural innovators,” and provides the following succinct description in support of his thesis:

New paradigm Christians are pioneering a new epistemology, one that seeks to move beyond the limitations of the Enlightenment-based understanding of religion that informs most modern critics of religion (e.g., Hume, Freud, Marx) and makes room for realities that do not nicely fit within the parameters of a materialistic worldview. Detached reason, they contend, is not the only guide to things ultimate. They believe religious knowledge is to be found in worship and in the spiritual disciplines associated with prayer and meditation—that the acts of singing, praying, and studying scripture offer insight. They follow the long history within the Christian tradition of referring to these moments as the presence of the Holy Spirit.

The Toronto Blessing provides a good illustration of how American Protestantism is being “reinvented” through contemporary religious experiences. The Blessing’s history, as for most of Protestantism, rests in the Reformation and its emphasis on the Bible as a foundation for all Christian truth. Most followers would accept the tenets of Christianity as found in the Nicene Creed. But the Blessing also finds validity in the historical religious experiences closer to home, comparing Toronto ‘s to those of the First Great Awakening. Guy Chevreau, a Baptist minister who had studied revivals while pursuing his Th.D. at Wycliffe College (Toronto School of Theology), was among the earliest visitors to the TAV revival. He linked what he observed there with his historical knowledge of Jonathan Edwards and the manifestations that occurred during the Great Awakening. Chevreau (1994) quickly became the in-house theologian during the early years of Toronto who could respond to queries about the controversial physical manifestations through his preaching and teaching classes at TAV/TACF and around the globe.

The populist theology that has come to mark the movement is not grounded in systematic theologies or in the curriculum of its accredited schools. It is developed by emerging leaders from varying Protestant sectors, many of who were not schooled in seminaries. Its theology is derived from empirical observations and religious testimonies sorted through innovative biblical interpretations. The simple motto once found on the wall of the TAV/TACF worship center became a basic tenet: “To know God’s love and to give it away” [now expanded to read “Walking in the Father’s love and giving it away to Toronto and to the world” (Steingard with Arnott 2014: 180)]. The experiential knowledge of divine love is assumed to be the propelling force (grace) that enables loving others. A kind of reiteration of the Great Commandment, the motto has found some support in empirical research conducted on the Blessing (c.f., Poloma 1996, 1998; Poloma and Hoelter 1998) as well as through research on mainstream America (Lee, Poloma and Post 2013).

This theology of love that marks the Blessing centers on experiencing the triune God (Father, Son and Spirit) of Christianity and teachings on the experiential “gifts of the Spirit,” namely, prophecy and divine healing. (It is significant that although most people who experience the Blessing do “pray in tongues” and that glossolalia had been the spiritual signature for most involved in the first two waves of pentecostalism, leaders of the Blessing have placed little doctrinal emphasis on tongues.) At times the life of Jesus and many of his teachings seem to fade into the background with Blessing teachings highlighting the power of the Holy Spirit and the Father’s love. As a warning against a literal interpretation of the scriptures without guidance from the Spirit, speakers would also remind listeners, “The trinity is not the Father, Son and the Bible, but the Father, Son and the Holy Spirit,”

John Arnott, as previously noted, prefers the term “Father’s Blessing” to “Toronto Blessing” for designating the worldwide movement that developed out of the revival. In writing on its history, Jerry Steingard with John Arnott (2014) made the following statement to open their discussion of theology:

To more fully understand or appreciate all that God has been accomplishing in this outpouring since 1994, we believe it is helpful and accurate to view it as a Father movement. The Father has been throwing a party, celebrating us coming home and back into his loving embrace. Through this extravagant outpouring of God’s love and grace, untold thousands, if not millions of us, have found deeper levels of healing and restoration in our hearts and relationships, and have come into greater intimacy and communication with our God. Out of the Father’s affirmation and blessing, we have been freshly awakened to who we are in Christ Jesus, to our true identity as royal sons and daughters and to our true calling and destiny.

Healing (spiritual, mental, physical, and relational) has been a central tenet for the Blessing that can be traced to a prophetic dream Arnott had in 1987 in which he reporting seeing “three bottles of cream”(Steingard with Arnott 2014:272-76). He says that in it he heard the Lord tell him to go to Buffalo, New York, to a dairy to get the three bottles (which he interpreted as being called drink from three distinct teachings). Arnott made a trip to Buffalo to meet with Tommy Reid, an Assemblies of God pastor known for the fresh move of the Holy Spirit that his congregation was enjoying in the 1980s. Reid in turn introduced Arnott to Mark Virkler whose teachings on experiencing God would provide the spiritual contents for one bottle, namely, how to commune with God through whom all healing comes. Experiencing the divine presence arguably is core to the Toronto movement. Carol and John Arnott had already been exposed to what they believed to be the contents of the two other bottles of cream: the first containing experiences of the Father heart of God that they had come to know through the ministry of Jack Winter and the other being the inner healing ministry of John and Paul Sanford. The Arnotts believe that “drinking” of these three teachings (communing with God, Father-heart of God, and divine inner healing) had prepared them and their congregation for the outpouring of God’s Spirit that became known to the world as the Toronto Blessing.

Two supporting and recurrent teachings for the “three bottle” theology can be found in the teachings on topics like prophecy, forgiveness, and holistic healing. Prophecy or hearing the (usually inaudible) voice of God is regarded as a normal phenomenon for revivalists who commune with the divine. Sometimes what is heard is the foretelling of future events but prophecy as forth-telling through which God provides comfort, guidance and support is more commonly practiced (Poloma and Lee 2013a, 2013b). Although end-time prophecies were introduced to both earlier waves of pentecostalism, the Toronto prophets are soft on the pre-millennial eschatology characteristic of fundamentalist Christianity. Instead the focus is on a Kingdom of God that is partially here with the potential of it being more fully becoming a reality through the power of the Holy Spirit. It may include foretelling , as when Marc Dupont and others foretold a promised revival in Toronto before it actually occurred and when Dupont prophetically instructed the Arnotts to relocate in Toronto (Steingard with Arnott 2014). John Wimber was involved with prophetic foretelling in the mid-1980s through a group known as the Kansas City Prophets (e.g., Bob Jones, Paul Cain, Mike Bickle, and John Paul Jackson). When a major prophecy of a KCP failed to actualize, Wimber continued to acknowledge prophecy as a gift of the Spirit, but he pulled away from his earlier support of the KCP who promoted the “office of prophet” and prophetic foretelling. Wimber stated his position as one in which “the prophets would not be loose cannons on the Vineyard ship; they would be bolted down to the deck, or they would be told to exercise their gifts elsewhere” (Beverley 1995:126; see also Jackson 1999).

The KCP and growing number of other prophets found a welcoming platform in Toronto , where they prophesied and modeled prophecy. While not everyone is called to the office of a prophet, all believers are said to be able to prophesy, thus not limiting its use to those who are acclaimed as prophets. Prophets were unofficially charged with modeling prophecy and instructing followers to how to prophesy (primarily in forth-telling), using this gift to encourage and to build the faith of others. John Arnott’s approach to prophecy (as seen in his use of prophecy to interpret some of the strange manifestations seen during the Toronto revival as “prophetic symbols”) is one of the reasons Wimber gave for dismissing the TAV from the AVC in 1995. Arnott (2008:52) would later write a booklet (elaborating the chapter on “prophetic mime” found in his 1995 book) that incorporated a discussion of the unusual manifestations found in the Bible and examples of manifestations seen in Toronto over the years. Arnott wrote:

We must learn to pay attention to what the Holy Spirit is saying and doing and exercise discernment when people are acting under His power. They could be demonstrating a powerful word the God wants us to hear. We need to be led by the Spirit and remember to be childlike, but not childish, in approaching the things of the Spirit. Let God be God. ‘Prove all things and hold fast to what is good.’

Promoting the loving “heart of the Father” (often delivered as personal prophetic forth-telling to individuals) replaced a rigid image of the Father as a stern judge and avenger, an image that is basic to Arnott’s theology of love and grace. This increasingly popular image of God has been described as “percolating beneath the surface for a very long time, a significant shift, a new pulse of the Spirit that may never have an identifying name.” E. Loren Stanford (2013) suggests a link between this shift in the image of God the Father and divine inner-healing when he writes:

Jesus, however, came to reveal the nature and character of His Father. “He who has seen Me has seen the Father” (John 14:9). We experienced wonderful years of revelation from great men like Jack Winter and Jack Frost who convinced us on no uncertain terms that the Father loves us. They brought healing to a generation wounded by the fatherlessness that grew from our culture of self.

Another important key (arguably the most important key) to Blessing theology is forgiveness. Arnott (1997P5) contends: “Forgiveness is the key to blessing. Forgiveness and repentance open up our hearts and allow the river of God to flow freely in us.” Failure to forgive wrongs committed against us, wielding the hammer of justice rather than the flag of mercy, and the failure to forgive oneself all can block communing with God, divine healing and supernatural empowerment. Forgiveness thus is said to be the key to loving others as we have been divinely loved. In sum, Arnott has identified three things that he regards as “vital to seeing the powerful release of the Spirit of God”:

First, we need a revelation of how big God is. We must know that absolutely nothing is impossible for Him (Luke 1:37). Second, we need a revelation of how loving He is, how much he cares for us and how He is absolutely committed to loving us to life (Jeremiah 31:3). I delight to tell people that God loves them just the way they are, yet loves them too much to leave them the way they are. Finally, we need a revelation of how we can walk in that love and give it away. A heart that is free has time and resources for others.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The late Clark H. Pinnock, noted theologian of Pentecostalism and professor at McMaster Divinity College in Ontario, who came to  TAV as a scholar-observer turned pilgrim, provides some insightful text about the interrelationship of religious experience, rituals, and theology based on his visits to TAV/TACF. Pinnock (2000:4-6) writes:

TAV as a scholar-observer turned pilgrim, provides some insightful text about the interrelationship of religious experience, rituals, and theology based on his visits to TAV/TACF. Pinnock (2000:4-6) writes:

The essential contribution of the Toronto Blessing lies in its spirituality of playful celebration. The Day of Pentecost (let us not forget) was a festival in the Jewish calendar and its festive character is evident in the Toronto meetings—in the joy and laughter of God’s children playing in the presence of God. When the music sounds, the people burst into joyful praise and abandon themselves to the love of God being poured out. . . .

The worship in Toronto is the ancient liturgy of the Church realized, with its many parts present but unnamed: the call, the Gloria, the kyrie, the confession, the Word, and the benediction. The old structures are there and are now carried along by an oral tradition that allows for both form and freedom. As is characteristic of jazz music, themes are pronounced by leaders but are also enriched by improvisation coming from the people and fueled by testimonies of what the Lord has done. The Scriptures are expounded, not literalistically, but charismatically, such that the Word of the Lord sounds fresh from the ancient texts. In a playful interaction between what the Bible presents and the present situation, the story life of Scripture gets interwoven with the life of the community so that we recognize ourselves in the text and are challenged by the living Word.

Pinnock’s assessment provides a thoughtful description of the playfulness found in the ritual of the renewal services and conferences, particularly during the earliest years of the revival. But even then the regular Sunday morning services at TAV/TACF customarily had a less playful timbre, and eventually even special conferences assumed a more predictable format. Ritual for a typical Sunday service (even during the heyday of revival) looked much like the rituals as practiced by countless non-liturgical evangelical and pentecostal churches throughout North America . Playful laughter, dancing, running falling, and a myriad of other strange antics, if they occurred at all in the regularly scheduled church services, were likely to be subdued and short lived.

The revival services at Toronto and the scores of places across the globe to which the Blessing spread had a simple format but one in which the Spirit and pilgrims were given the space and encouragement to play. A typical revival service at TAV/TACF lasted at least two and a half hours, plus an undefined number of hours following for individual ministry. The format included the following components: worship in song and dance; testimonies about the experience and effects of the blessing; announcements, offering and song; preaching/teaching; altar call for salvation and recommitment; and service dismissal with the informal general ministry time to follow. But no one was rigidly following format or a calling time on a particular component. As Steingard with Arnott (2014:261) commented about the basic format, “[It] does not reflect the holy chaos that was often the norm.” They went on to say: “And the Holy Spirit often came and vetoed or hijacked the meeting, particularly during the testimony times. Occasionally the scheduled speaker was unable to give his message, and ministry time often went on until one or two in the morning, with some people needing to be carried out to their cars in order to close the church doors for the night!”

Nightly revival meetings at TACF and other Blessing locations were more concerned about “allowing the Spirit to move” than protecting a schedule or developing a structured ritual. Revival services provide a good example of what anthropologist Victor Turner has called “antistructure” in his discussion of ritual and its relationship to “liminality” (Turner 1969). For Turner, “liminality” is a qualitative dimension of the ritual process that often appears in efficacious ritual, operating “betwixt and between” or “on the edge of” the normal limits of society. Liminal conditions, which can range from dancing to the strong beat of Christian rock music (as found in contemporary revivals) to sitting in stillness and silence (as found in Silent Quaker meetings), are reflections of “antistructures” that make space “for something else to occur.” Toronto ‘s nightly revival meetings and conferences were open to the unexpected, intentionally sorting out only behaviors which were deemed to be potentially harmful. The Arnotts believed an earlier heavy-handed response to unfamiliar manifestations stifled a revival that had developed some years earlier in their church in Stratford , Ontario — and they were determined not to make the same mistake with the Toronto Blessing. When new developments would emerge John Arnott or one of the leaders might ask the person involved what he or she was experiencing.

An illustration of the interpretation of a controversial manifestation and its perceived effects can be seen the first time roaring occurred during a meeting in the spring of 1994. John Arnott was in St. Louis visiting Randy Clark when an Asian pastor from Vancouver, British Columbia roared like a lion. When Arnott returned to Toronto, Gideon Chu was still there; Arnott invited him to the platform to explain why he had roared. “Gideon testified that he thought the roaring represented God’s heart over the heritage and domination of the dragon over the Chinese people. He felt that Jesus, the Lion of the tribe of Judah , was going to free the Chinese people from centuries of bondage” (Steingard with Arnott 2014:157). Nearly twenty years later at the Revival  Alliance 2014 Conference held in Toronto, Carol Arnott (2014) updated the audience about the prophetic symbolism of Chu ‘s roaring. After not hearing from him for years, Chu reconnected with the Arnotts in the fall of 2013 and was invited to a Partners in Harvest gathering to share his story. Carol retold Chu’s story, noting that Chu thanked them for not shutting him down when he roared like a lion in 1994. She then showed a film clip of Chu’s involvement with top Christian leaders in China who have been instrumental in bringing an estimated fifty to sixty million Chinese people to Christianity (Carol Arnott, 2014). The emphasis then and now has been on judging the testimonies and potential effects of manifestations rather than outlawing them simply because they seemed “weird.” The case of Pastor Chu roaring like a lion demonstrates how the loose structure and flexible norms at TAV/TACF creates space for “liminality” to flourish.

Alliance 2014 Conference held in Toronto, Carol Arnott (2014) updated the audience about the prophetic symbolism of Chu ‘s roaring. After not hearing from him for years, Chu reconnected with the Arnotts in the fall of 2013 and was invited to a Partners in Harvest gathering to share his story. Carol retold Chu’s story, noting that Chu thanked them for not shutting him down when he roared like a lion in 1994. She then showed a film clip of Chu’s involvement with top Christian leaders in China who have been instrumental in bringing an estimated fifty to sixty million Chinese people to Christianity (Carol Arnott, 2014). The emphasis then and now has been on judging the testimonies and potential effects of manifestations rather than outlawing them simply because they seemed “weird.” The case of Pastor Chu roaring like a lion demonstrates how the loose structure and flexible norms at TAV/TACF creates space for “liminality” to flourish.

The “general ministry time” that followed the revival service (dubbed “carpet time” by many) consciously allowed a place and time to enjoy unbridled play and prayer. After the regular service ended, many lined up for prayer seeking the presence and power of the Holy Spirit, while others lay on the floor or sat in their seats often in seemingly altered states. The hours that followed allowed ample opportunity for worshipers to experience the mystical, including visions, dreams, healing, prophecy, as well as the often-noted physical manifestations, including holy laughter and being “drunk in the spirit” (Poloma 2003). Hundreds of people would line up nightly for prayer ministry by teams of pray-ers in a loose ritual accompanied first by the worship band and then transitioning to CDs as the night progressed. For many this post-service ministry would be the highpoint of the evening.

Those seeking prayer during the general ministry time were instructed to line up on the neatly marked floor, as prayer teams with  the assistance of a “catcher” who stood behind the pray-ee (to assure no one was injured in the fall) would offer informal prayer. On any given night rows upon rows of bodies could be found sprawled out over the floor. “Carpet time” with pray-ees dropping faint to the floor (also known as “going under the power,” “being slain in the spirit” or “resting in the spirit” in earlier waves of pentecostalism) was widespread at TAV/TACF. Scores of trained prayer team members would minister nightly to the hundreds of individuals who lined up for prayer at the end of each service. “Carpet time” differed from the earlier practice of “resting in the spirit” that was widespread during the second wave of pentecostalism in its duration and democratization. No longer was the pastor or conference leader the person responsible for praying for the masses; prayer teams, made up of scores of volunteers, became an important medium for the Blessing. While falling to the ground in a seeming trance was a common experience in the second pentecostal wave, pray-ees would normally quickly get up and return to their seats. Toronto pilgrims, however, were instructed not to be in a hurry to rise from the floor. Waves of the Spirit’s manifest presence could keep coming, so it was important to wait and to “soak” in the divine presence allowing God time to fully impart His blessing. Falling to the ground and other physical manifestations were not limited to the church auditorium, they could be seen in hotel lobbies, restaurants and even parking lots, particularly during the earliest years of the revival. (Drivers would jovially be warned that bodies seen in the parking lot were not put there as speed bumps.)

the assistance of a “catcher” who stood behind the pray-ee (to assure no one was injured in the fall) would offer informal prayer. On any given night rows upon rows of bodies could be found sprawled out over the floor. “Carpet time” with pray-ees dropping faint to the floor (also known as “going under the power,” “being slain in the spirit” or “resting in the spirit” in earlier waves of pentecostalism) was widespread at TAV/TACF. Scores of trained prayer team members would minister nightly to the hundreds of individuals who lined up for prayer at the end of each service. “Carpet time” differed from the earlier practice of “resting in the spirit” that was widespread during the second wave of pentecostalism in its duration and democratization. No longer was the pastor or conference leader the person responsible for praying for the masses; prayer teams, made up of scores of volunteers, became an important medium for the Blessing. While falling to the ground in a seeming trance was a common experience in the second pentecostal wave, pray-ees would normally quickly get up and return to their seats. Toronto pilgrims, however, were instructed not to be in a hurry to rise from the floor. Waves of the Spirit’s manifest presence could keep coming, so it was important to wait and to “soak” in the divine presence allowing God time to fully impart His blessing. Falling to the ground and other physical manifestations were not limited to the church auditorium, they could be seen in hotel lobbies, restaurants and even parking lots, particularly during the earliest years of the revival. (Drivers would jovially be warned that bodies seen in the parking lot were not put there as speed bumps.)

Leslie Scrivener, a reporter for The Toronto Star (October 8, 1995), began her news article on a TAV conference with the following playful description that characterized the revival:

The mighty winds of Hurricane Opal that swept through Toronto last week were mere tropical gusts compared with the power of God thousands believe struck them senseless at a conference at the controversial Airport Vineyard church. At least with Opal, they could stay on their feet. Not so with many of the 5,300 souls meeting at the Regal Constellation Hotel. The ballroom carpets were littered with fallen bodies, bodies of seemingly straightlaced men and women who felt themselves moved by the phenomenon they say is the Holy Spirit. So moved, they howled with joy or the release of some buried pain. They collapsed, some rigid as corpses, some convulsed in hysterical laughter. From room to room come barnyard cries, calls heard only in the wild, grunts so deep women recalled the sounds of childbirth, while some men and women adopted the very position of childbirth. Men did chicken walks. Women jabbed their fingers as if afflicted with nervous disorders. And around these scenes of bedlam were loving arms to catch the falling, smiling faces, whispered prayers of encouragement, instructions to release, to let go ” [italics added for emphasis].

As a participant observer of TAV/TACF, particularly during the first six years of the revival during which I often served on prayer teams, I can personally attest to a sense of peace that mysteriously permeated the audible and visible bedlam of revival. My first impression during my initial visit to TAV (November 1994) meshed well with Scrivener’s concluding sentence. I recall standing in line for a couple of hours talking with other pilgrims outside the industrial strip mall on Dixie Road, for what would be one of the last services held at this location where pilgrims outnumbered the seats in the small church. We arrived early, standing outside in the cold Canadian weather with hopes of being among those who would be admitted to the main room, or at least into the overflow section. Although I was a seasoned pentecostal observer, I had never before experienced the unusually spirited service of worship in song, testimonies, and sermon that was permeated by various physical manifestations, especially “holy laughter.” After the general service ended and the chairs were gathered up to make room for individual ministry, I found a small spot on the floor next to a pillar where I enjoyed a ring-side seat during “carpet time.” I listened to the prayer teams as they playfully ministered to visitors (most of whom seemed to quickly sink to the floor) with simple phrases, the most common of which seemed to be “more, Lord – give (him or her) more.” There was little exchange about personal needs or problems nor the saying of well-articulated flowing prayers that I was used to from serving on prayer teams in charismatic churches. “More, Lord” seemed to suffice.

Over the years “carpet time” would morph into what became known as “soaking prayer,” a ritual practice and (for a few years) a  potential religious movement in its own right. Soaking prayer has been defined (von Buseck, n.d .) as “simply positioning yourself to express your love to God. It is not intercession. It is not coming to God with a list of needs. It is the act of entering into the presence of God to experience His love — and then allowing the love of God through the Holy Spirit to revolutionize your love for Him.”

potential religious movement in its own right. Soaking prayer has been defined (von Buseck, n.d .) as “simply positioning yourself to express your love to God. It is not intercession. It is not coming to God with a list of needs. It is the act of entering into the presence of God to experience His love — and then allowing the love of God through the Holy Spirit to revolutionize your love for Him.”

Instead of seeking prayer from a prayer team that preceded the prayee’s falling to the floor, some men and women would simply lie down (often equipped with a “soaking prayer kit” of blanket and pillow) or to sit comfortably as they listened to the music and surrendered to whatever might follow. With appropriate “soaking music” playing in the background, pray-ers and pray-ees worked together to create space for entering the divine presence sought by mystics over the centuries (Wilkinson and Althouse 2014).

By 2004, a plan was afloat to spread the Blessing by establishing soaking prayer centers throughout the world under the CTF rubric. John and Carol Arnott produced a Soaking Kit of six DVDs, soaking prayer leaders gave talks, videos promoting soaking prayer appeared on YouTube, and a network was established to encourage the practice that claimed “77 countries and growing.” CTF’s plans to keep renewal fires burning through soaking prayer centers seem to have been short lived, with only a small description on the present website that includes the warning: “P lease note: Some of the administrational information in this video is slightly out of date, however the key principles remain true”(“Soaking” n.d.).

Over the years that followed the birth of the Toronto Blessing, particularly within the first decade after the famed service of January, 1994, events would erupt at both Toronto and elsewhere to fan revival fires. They included new revival sites (with strong or weak ties to Toronto) at Pensacola, Florida (Brownsville Assembly of God), Smithton, Missouri (Smithton Community Church), Pasadena, California (Harvest Rock Church), Baltimore, Maryland (Rock City Church); Redding, California (Bethel Church Assembly of God), and the Canadian Arctic Outpouring (various communities in the Canadian territory of Nunavut). In 1999, reports of golden flakes and gold fillings (noted during the 1980s at the Argentinean revival) made their way to Toronto – an outbreak that John Arnott explained by saying “I just believe God loves people and wants to bless them” (Steingard with Arnott 2014:201; see also Poloma 2003). Whatever the medium, visiting pastors and lay pilgrims would not uncommonly “catch the fire” and carry seemingly strange outcomes (from “holy laughter” to “gold fillings”) back to their home churches.

Most of the playful rituals and experiences of Toronto were defined in terms of God’s manifest presence and power, and especially as a sign of God’s deep and personal love. Although there were some early attempts to lead revivalists into the city of Toronto to feed the poor and the homeless, most visitors did not make the trek to TAV/TACF to do social outreach. A survey of Toronto pilgrims did indicate, however, that the majority were involved serving those in need in some way (and those who scored higher on reported experiences of divine love) were the most likely to be involved in outreach to the poor and needy (see Poloma 1998). The nightly revival meetings, however, seemed focused on receiving personal spiritual blessings. Heidi and Rolland Baker,  American missionaries to Mozambique, embraced the personal blessing but coupled it with exemplifying its power to serve the poor. First Rolland and then Heidi came to Toronto in 1996, as burned-out pilgrims who needed spiritual refreshing to maintain their newest ministry in a country that was just emerging from a long civil war. They would become living examples of how personal spiritual blessings can empower extraordinary love and service. Heidi (sometimes lovingly referred to as a pentecostal Mother Teresa) has especially captured the hearts of those involved in the Blessing with her testimonies (many are found on YouTube) of how visits to Toronto have changed her life and empowered their ministry (Stafford 2012). Her accounts have provided the revival movement with stories of miracles far surpassing those customarily heard in North America, accounts coupled with her compelling call to love God and to love the poor (Baker and Baker 2002; Baker 2008; see also Lee, Poloma and Post 2013 for further discussion). The Bakers not only breathed new life into the Toronto Blessing but they continue to serve as an important link among those involved in the web-like Partners in Harvest and Revival Alliance, two organizations in which different ministries work together toward the common goal of promoting revival.

American missionaries to Mozambique, embraced the personal blessing but coupled it with exemplifying its power to serve the poor. First Rolland and then Heidi came to Toronto in 1996, as burned-out pilgrims who needed spiritual refreshing to maintain their newest ministry in a country that was just emerging from a long civil war. They would become living examples of how personal spiritual blessings can empower extraordinary love and service. Heidi (sometimes lovingly referred to as a pentecostal Mother Teresa) has especially captured the hearts of those involved in the Blessing with her testimonies (many are found on YouTube) of how visits to Toronto have changed her life and empowered their ministry (Stafford 2012). Her accounts have provided the revival movement with stories of miracles far surpassing those customarily heard in North America, accounts coupled with her compelling call to love God and to love the poor (Baker and Baker 2002; Baker 2008; see also Lee, Poloma and Post 2013 for further discussion). The Bakers not only breathed new life into the Toronto Blessing but they continue to serve as an important link among those involved in the web-like Partners in Harvest and Revival Alliance, two organizations in which different ministries work together toward the common goal of promoting revival.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Catch the Fire had its roots in an independent non-denominational church, Jubilee Christian Fellowship in Stratford, Ontario,  established by John Arnott in 1981. Arnott met John Wimber, founder of the newly formed Association of Vineyard Churches, in 1986; a year later he and his church would join the AVC. The Toronto Airport Vineyard (TAV) began as an AVC “kinship group” planted by John and Carol Arnott in 1988 (then known as Vineyard Christian Fellowship Toronto but renamed when another Vineyard church opened in Toronto ). In 1991, the Arnotts moved to Toronto and began to assemble a staff for their new church. The “Toronto Blessing” revival erupted in January, 1994 and tension would soon develop between the TAV and the AVC. TAV would be formally dismissed from the AVC by Wimber in late 1995, largely over disagreements about particular ritualistic practices (including “carpet time” and “prophetic mime”). A new church organization focusing on revival would be born.

established by John Arnott in 1981. Arnott met John Wimber, founder of the newly formed Association of Vineyard Churches, in 1986; a year later he and his church would join the AVC. The Toronto Airport Vineyard (TAV) began as an AVC “kinship group” planted by John and Carol Arnott in 1988 (then known as Vineyard Christian Fellowship Toronto but renamed when another Vineyard church opened in Toronto ). In 1991, the Arnotts moved to Toronto and began to assemble a staff for their new church. The “Toronto Blessing” revival erupted in January, 1994 and tension would soon develop between the TAV and the AVC. TAV would be formally dismissed from the AVC by Wimber in late 1995, largely over disagreements about particular ritualistic practices (including “carpet time” and “prophetic mime”). A new church organization focusing on revival would be born.

By January, 1996, the second anniversary of the revival, the now independent church was renamed the Toronto Airport Christian Fellowship (TACF) and relocated in a large newly renovated building near the airport on Attwell Drive that had been acquired a year earlier. In 2010, the church that hosted the Toronto revival would be renamed once more, this time, as Catch the Fire Toronto (CTF). Steve and Sandra Long had been associate pastors at TACF/CTF since 1994, when after visiting TAV they resigned from the  Baptist tradition to align with TAV (Steingard with Arnott 2014). In January, 2006, Steve and Sandra (married couples are generally regarded as a ministerial team) were made senior pastors (senior leaders) of the Toronto CTF church and John and Carol assumed the title of “founding pastors.” The Arnotts also serve as President of Catch the Fire (World), with Steve and Sandra Long and Duncan and Kate Smith (of CTF Raleigh, North Carolina) serving as vice-presidents.

Baptist tradition to align with TAV (Steingard with Arnott 2014). In January, 2006, Steve and Sandra (married couples are generally regarded as a ministerial team) were made senior pastors (senior leaders) of the Toronto CTF church and John and Carol assumed the title of “founding pastors.” The Arnotts also serve as President of Catch the Fire (World), with Steve and Sandra Long and Duncan and Kate Smith (of CTF Raleigh, North Carolina) serving as vice-presidents.

It is safe to say that the shifting organizations, leaders and nomenclature coming out of the Toronto Blessing have always been more web-like than organizational, based on loose relationships rather than on well-defined membership criteria. What exists today as CTF and the umbrella networks Partners in Harvest and Revival Alliance may be shifting even as this section is being written. Partners in Harvest was originally established by John Arnott in response to the request of pastors immediately following the dismissal of TACF from the AVC in late 1995 as these leaders sought a “covering” for their ministries. In 1996, Partners in Harvest was birthed, to serve as a network of fellowship for leaders of churches and ministries who had embraced the revival. Those who did not wish to commit (or felt they could not commit because of particular denominational affiliations) could become Friends in Harvest. Partners in Harvest has most recently been described as a “family of churches . . . [consisting] of about six hundred  churches and ministries worldwide with one hundred and fifty of those considered as ‘Friends in Harvest’” (Steingard with Arnott 2014:224). The PIH website (“Revival Alliance Conference” 2014) described Partners in Harvest as serving “PIH family members’ primary relational affiliation and covering” and as a “primary source of accountability.” The purpose of PIH is “to provide encouragement, blessing and a relational network for the building up of its members.”

churches and ministries worldwide with one hundred and fifty of those considered as ‘Friends in Harvest’” (Steingard with Arnott 2014:224). The PIH website (“Revival Alliance Conference” 2014) described Partners in Harvest as serving “PIH family members’ primary relational affiliation and covering” and as a “primary source of accountability.” The purpose of PIH is “to provide encouragement, blessing and a relational network for the building up of its members.”

There is also another relational umbrella of “friendship and interdenominational unity” known as Revival Alliance in which CTF is one of six members. Revival Alliance is a network made up of revival leaders, each of whom heads an independent ministry with its own structure and goals. Although claiming to be “interdenominational,” all have been influenced by the Toronto Blessing and all have played some role in promoting and shaping its history. None belong to recognized established denominations. They include John and Carol Arnott (Catch the Fire); Randy and DeAnne Clark (Global Ministries); Bill and Beni Johnson ( Bethel Church , Redding ), Rolland and Heidi Baker ( Iris Ministries ), Che and Sue Ahn (Harvest International Ministry), and Georgian and Winnie Banov (Global Celebration) (Steingard with Arnott 2014:225). Together they recently hosted a large conference in Toronto to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the Toronto Blessing (“Revival Alliance Conference” 2014).

Catch the Fire can be described as but one, albeit arguably the most significant, of an independent network of churches and ministries that aligns with the Revival Alliance and Partners in Harvest. On another level, CTF can be described as an international denomination in the making. As we have noted in giving an account of the birth of TAV/TACF/CTF, the Toronto church began as a “cell group”; “cells” are still regarded as important seeds for future CTF churches. CTF presently has ten church campuses, including two in the United States (Houston, Texas and Raleigh, North Carolina) and four in Canada (Toronto, Ontario; Montreal, Quebec; Halifax, Nova Scotia; and Calgary, Alberta) (Steingard and Arnott 2014:226). All are members of Partners in Harvest and all are encouraged to develop cell groups through their congregations. Catch the Fire has a reported 200 cells in the Greater Toronto Area and eight campuses (churches at different GTA locations) in addition to the original Airport campus, describing itself as a “multicultural and multi-campus cell church” (Catch the Fire Campuses n.d.). In addition to the growing network of churches in the Toronto area, CTF Toronto conducts a school of ministry known as Catch The Fire College, with similar Catch the Fire Colleges in Montreal, South Africa, the UK, Norway, the USA and Brazil (Steingard and Arnott 2014:273). Although it no longer holds nightly revival meetings, CTF regularly hosts conferences and an on line video site (Catch the Fire TV hosted by YouTube). A team of itinerant CTF, Partners in Harvest, and Revival Alliance ministers continue to spread the word about revival in churches around the globe.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Issues and challenges that face the Toronto Blessing Movement/Catch the Fire can be approached through the lenses of theology and sociology, both of which have been implicit in recounting the history and organization of this revival movement. The Toronto Blessing is rooted in populist theologies linked to mysticism , a theological construct that focuses more on affective experiences than intellectual dictums . Mysticism has been defined as “a religious practice based on the belief that knowledge of spiritual truth can be gained by praying or thinking deeply” and the “belief that direct knowledge of God, a spiritual truth, or ultimate reality can be attained through subjective experience” (Meriam Webster Dictionary 2014). While those involved in the CTF movement would be unlikely to use the term, Poloma (2003) has demonstrated how scholarly literature on mysticism contributes to understanding the altered consciousness and alternate world view in which pentecostal experiences (including the strange physical manifestations) are often perceived to be encounters with the divine. Sociology , on the other hand, is the social scientific study of human social behavior, including empirical description and critical analysis of the interaction between human behavior and social organization. It can neither prove nor disprove the authenticity of mystical experiences. Sociological theories and methods, however, can be applied to the empirical study of the role that religious experience plays in the origin, development and revitalization of organized religion, including the web-like organizations of much of contemporary pentecostalism (c.f. Poloma 1982; 1989; Poloma and Green, 2010).

Karl Rahner, a renowned Catholic theologian said (in an often cited quotation): “In the coming age we must all become mystics—or be nothing at all” (c.f. Tuoti 1996). Rahner’s observation casts light on understanding the exponential growth of global pentecostalism over the past one hundred years. Recent neo-pentecostal revivals, including the Toronto Blessing, with its emphasis on prophecy, visions, dreams, and other paranormal experiences have been largely ignored by academic systematic theology and severely critiqued by populist cessationists who deny the relevance of biblical paranormal experiences (tongues, prophecy, miracles, etc.) for contemporary Christianity. The Blessing movement has its populist supporters and its critics. The most vocal and influential of the conservative populist critics is Hank Hanegraaff (1997), an ordained minister in Chuck Smith’s  Calvary Chapel network, President of the Christian Research Institute, and host of The Bible Answer Man radio-talk show. Hanegraaff has pejoratively described the revival movement as “spiritual cyanide” that is “aping the practices of pagan spirituality” with leaders who “work their devotees into an altered state of consciousness” (cited in Steingard with Arnott 2014:148).

Calvary Chapel network, President of the Christian Research Institute, and host of The Bible Answer Man radio-talk show. Hanegraaff has pejoratively described the revival movement as “spiritual cyanide” that is “aping the practices of pagan spirituality” with leaders who “work their devotees into an altered state of consciousness” (cited in Steingard with Arnott 2014:148).

While Hanegraaff has extensively critiqued revival experiences as an outsider to the pentecostal movement, Andrew Strom, a self-described charismatic who had once been actively involved with the Kansas City Prophets and accepts a theology of the gifts of the Spirit, proffers an “insider’s warning.” Not unlike Hanegraaf, Strom has launched a harsh and relentless critique that labels contemporary revivals to be “false” and “demonic” (Strom 2012). He regards the physical manifestations as “false spirits” of Eastern mysticism, specifically linking them to the “Hindu ‘Kundalini’ spirit” and New Age teachings (Strom, 2010). More moderate critics like James Beverly (1995), while still reluctant to interpret the more extreme physical manifestations as direct manifestations of the Holy Spirit, have softened their assessment of the revival over the years. Beverly is reported as saying, “Whatever the weaknesses are, they are more than compensated for by thousands and thousands of people having had tremendous encounters with God, receiving inner healings, and being renewed” (Dueck 2014).

The Revival Alliance’s support of Todd Bentley’s failed Lakeland ( Florida ) Revival that lasted for only four months in 2008 gave  new fuel to revival critics. Strom (2012, 29) writes:

new fuel to revival critics. Strom (2012, 29) writes:

The Lakeland revival was almost certainly the most hyped event in Charismatic history. And yet it all ended in ignominy in August, 2008 . . .It went from the most hyped ‘great revival’ to one of the most regretted fiascos in Charismatic history within a matter of weeks. And at the very center of it was Todd Bentley’s affinity for strange ‘manifestations’ straight out of Toronto and the Prophetic movement.

Bentley’s use of “guided visualization;” his personal demeanor and extensive tattoos; repeated visions of Emma, a young beautiful female angel; his provocative ministry style (including crying out “Bam” while praying for people and even kicking persons being prayed for); and other flamboyancies fed many reservations about his popular revival. Yet during its four-month run it would draw thousands to Lakeland , Florida each night while multiple thousands more watched from around the world on God TV and the Internet. Three of the leaders of the Revival Alliance (John Arnott, Bill Johnson, and Che Ahn) would lay hands on Bentley on June 23, 2008 and anoint him, thus offering their public support for Bentley’s apostolic revival. The bombshell would come in early August when Bentley announced he was separating from his wife and “another woman” was involved. He would soon divorce his wife and remarry, turning the revival into a tailspin in August, 2008. With leading revival “apostles” and “prophets” having uncritically offered Bentley support despite his strange beliefs and practices (even by revival standards) followed by their attempt to quickly restore his ministry after the untimely divorce and remarriage, theological critics had new fuel to add to their critique of the Toronto Blessing and its followers.