Comunidade Nova Aliança (New Alliance Community)

COMUNIDADE NOVA ALIANÇA (CNA) TIMELINE

1983 (March 31): Eduardo Ramos was born in Governador Valadares, MG, Brazil.

1985 (March 26): Debora Oliveira was born in Brasília, DF, Brazil.

1986 (July 21): Jonathan Bolkenhagen was born in Planalto, RGS, Brazil.

2001: Eduardo Ramos moved to Australia with his parents.

2002: Debora Oliveira moved to Australia with her parents.

2002: Eduardo Ramos and Debora Oliveira met at the Brazilian church “Assembleia de Deus na Australia Church” (Assemblies of God in Australia)

2003: Eduardo Ramos and Debora Oliveira left “Assembleia de Deus na Australia Church” and joined another Brazilian church called “Assembleia de Deus na Australia Ministério Aguia.” This Brazilian church was located at Petersham Assemblies of God Church.

2006 (December): Brazilian pastor of “Assembleia de Deus na Australia Ministério Aguia” church moved to Queensland and left the church leaderless.

2007 (January): Pastor Barry Saar (Senior Minister at Petersham Assemblies of God Church) invited Eduardo Ramos to take over the Brazilian church.

2007 (February): Eduardo Ramos and Debora Oliveira founded CNA. Eduardo became its Pastor.

2007 (February): Eduardo Ramos and Debora Oliveira married.

2007-2008: Pastor Barry Saar played the role of senior Pastor of CNA and mentor for Eduardo and Debora while the couple studied at Alphacrucis College (a Christian tertiary college and official ministry training college of Australian Christian Churches, formerly the Assemblies of God in Australia).

2008: The first church camping trip took place over Easter.

2009 (March): Pastor Eduardo Ramos was ordained by the Australian Christian Churches (ACC) and became Senior Pastor of CNA church.

2007 (October): Brazilian student Jonathan Bolkenhagen arrived in Australia and joined CNA.

2012 (May 22): Jonathan Bolkenhagen graduated from Alphacrucis College.

2012 (June 21): Pastor Eduardo Ramos was fully ordained Minister of ACC.

2012 (November 22-25): The first CNA conference was held. Pastor Vinicius Zulato of Lagoinha Church in Brazil was a special guest.

2012: After the conference, Pastor Zulato taught a mini-course on Theology to CNA Pastors to strengthen their theological foundations.

2013: Congregation members moved to Adelaide and Canberra and opened CNA connect groups in each city.

2016 (August 27): CNA Canberra held its first service.

2016: Jonathan Bolkenhagen was ordained as pastor at CNA.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Eduardo Ramos [Image at right] arrived in Australia in 2001, when he was an eighteen year-old. Debora Oliveira arrived in 2002, when she was 16 years old. In Brazil they used to be members of Baptist churches. After they arrived in Sydney they joined and met each other at the only existing Brazilian church at the time: the Pentecostal church Assembleia de Deus na Australia Church (Assemblies of God in Australia), later renamed Igreja Avivamento Mundial (World Revival Church) (Rocha 2006). However, a year later, in 2003, the couple and a few others in the congregation left this church to join a new Brazilian church located in the premises of the Petersham Assemblies of God Church. They stayed in this new church called Assembleia de Deus na Australia Ministério Aguia until December 2006, when the Brazilian pastor moved to Queensland and left the church leaderless.

Debora Oliveira arrived in 2002, when she was 16 years old. In Brazil they used to be members of Baptist churches. After they arrived in Sydney they joined and met each other at the only existing Brazilian church at the time: the Pentecostal church Assembleia de Deus na Australia Church (Assemblies of God in Australia), later renamed Igreja Avivamento Mundial (World Revival Church) (Rocha 2006). However, a year later, in 2003, the couple and a few others in the congregation left this church to join a new Brazilian church located in the premises of the Petersham Assemblies of God Church. They stayed in this new church called Assembleia de Deus na Australia Ministério Aguia until December 2006, when the Brazilian pastor moved to Queensland and left the church leaderless.

As a result, in January of 2007 Pastor Barry Saar, the Senior Minister at Petersham Assemblies of God Church, asked the congregation to nominate someone to be trained as a Pastor to lead the church. The congregation chose Eduardo Ramos as their new Pastor. In February of 2007, Eduardo and Debora married and founded CNA. They agreed that Pastor Saar would mentor them while they studied at Alphacrucis College (a Christian tertiary college and official ministry training college of Australian Christian Churches). They were very young when they started the church (he was twenty-three and she was twenty-one); so in the first years they depended on Pastor Saar for almost everything (e.g., CNA’s theological foundations and constitution, directions on how to support congregation members and how to function as a church).

Eduardo and Debora thought their previous church was too conservative. This was so because it catered to the older generation of working class Brazilians who had arrived in Australia as part of a first wave of Brazilian migration (1970s-1990s). They wanted a less traditional church that would cater for the second wave of migration (late-1990s to present). This wave comprised of a growing number of young middle-class students who go to Australia to study English and possible migration (Rocha 2006, 2013, 2017). Eduardo and Debora envisioned a church where people could be free to dress informally, play worship music, [Image at right] and not stick too  strictly to a denomination so that they could be welcoming of young Brazilians from all walks of life. They also wanted a church heavily focused on supporting this new cohort of Brazilians arriving in Australia, as they arrived without their immediate family and were very young.

strictly to a denomination so that they could be welcoming of young Brazilians from all walks of life. They also wanted a church heavily focused on supporting this new cohort of Brazilians arriving in Australia, as they arrived without their immediate family and were very young.

Presently, the average age of congregation is twenty-five to thirty-five, and there are around ninety active members.However, because they are students in Australia, there is a high turnover in the congregation, with many arriving and others returning to the homeland. Many of them were not religious in Brazil and sought the church for emotional, social and financial support, and as a place to meet other Brazilians in the diaspora.

In 2016, another Brazilian member, Jonathan Bolkenhagen, [Image at right] was ordained pastor at CNA after graduating from  Alphacrucis College. In the same year Jonathan Bolkenhagen started commuting to Canberra to run a new branch of the church in the nation’s capital. This branch also caters for the Brazilian community there, but the congregation is a little older and comprised of families who have become Australian citizens. There are around thirty members in the Canberra congregation.

Alphacrucis College. In the same year Jonathan Bolkenhagen started commuting to Canberra to run a new branch of the church in the nation’s capital. This branch also caters for the Brazilian community there, but the congregation is a little older and comprised of families who have become Australian citizens. There are around thirty members in the Canberra congregation.

The church name can be explained in two parts: “New Alliance” refers to the alliance Jesus made at the cross with God. “Community” was chosen because the church is not representing any denomination in particular, although they are affiliated to the Australian Christian churches (former Assembly of God is Australia). The founders wanted to send a message that they accepted people from all denominations. In sum, they wanted to signal to this relationship with God and that they wanted to be a family (“community”) to followers. The church’s motto is: “a simple, happy, and transparent church.”

CNA uses the facilities of the Petersham Assemblies of God Church. Services are on Sunday evenings (as it is usual in Brazil), and therefore they do not clash with the regular English-language services on Sunday morning. CNA also has an office behind the church and is supported by Pastor Saar and his church.

Nevertheless, the founders have not circumscribed themselves to Pastor Saar’s church as a model for CNA. Given that they consider themselves non-denominational, they have continued looking for successful ways to establish themselves. One of the churches that inspires them is the Australian megachurch Hillsong (Connell 2005; Goh 2007; Riches and Wagner 2017; Rocha 2017, 2013; Wagner 2013). They admire Hillsong’s professionalism, success, informality, and non-judgemental and inclusive attitudes (in regards to dress, behaviour, and life situation) toward those who come to church. Hillsong works as a good role model because, like Hillsong, CNA is youth-oriented. CNA’s services are similar to Hillsong’s albeit on a much smaller scale: they feature a band; there is an informal atmosphere (in the Pastors’ and congregation’s language and dress style); the church is dark and real-time telecasts of the band and the song lyrics are beamed onto the screens beside the stage. Everyone in the congregation dances and sings together with the band. They may raise their arms, close eyes, or keep their hands on their hearts.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

CNA is a Pentecostal church affiliated to the Australian Christian Churches (formerly known as Assemblies of God in Australia). As such, it believes in spiritual gifts given by the Holy Spirit, such as glossolalia (speaking in tongues), divine healing, and prophesy. It also accepts the Bible as God’s word and believes that its lessons can be applied to people’s everyday lives.

Given that CNA is a church founded by Baptist Brazilians and is influenced by the Australian Pentecostal megachurch Hillsong, CNA has become a hybrid of a more traditional Brazilian Baptist church and a very informal, rock-concert-style Hillsong church.

On the one hand, like Hillsong, CNA can be considered a “New Paradigm” (Miller 1997) or “Seeker-friendly” church (Sargeant 2000). This style of evangelical Christianity has evolved globally since the 1960s and such churches “tailor their programs and services to attract people who are not church attenders” (Sargeant 2000:2-3). They do this by creating an informal atmosphere, using contemporary language and technology, and focusing on religious experience. Seeker churches borrow from secular models of business and entertainment, use marketing and branding principles, and innovative methods. According to Miller and Yamamori (2007:27), they “are at the cutting edge of the Pentecostal movement: they embrace the reality of the Holy Spirit but package religion in a way that makes sense to culturally attuned teens and young adults, as well as upwardly mobile people who did not grow in the Pentecostal tradition.” As a rule, their services are entertaining (featuring a live band, professional lighting and sound, large screens), and the focus is on people’s everyday lives (with topical messages on practical concerns).

On the other hand, while “New Paradigm” or “Seeker-friendly” churches focus on positive messages of God’s love rather than on sin, hell or damnation, CNA preaches also on the latter topics. CNA Pastors appreciate that young people may prefer a message of love, but they feel that they cannot focus on only love and should preach the Bible as a whole.

It is precisely this hybridity that attracts Brazilian students to CNA, as the church is able to function as a bridge between Brazilian and Australian societies and religious cultures (Rocha 2013).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Like other diasporic churches, CNA assists migrants in the process of overcoming nostalgia,homesickness and the challenge of adapting to the new country. [Image at right] CNA offers young Brazilians a space for community-building through services, weekly connect-group meetings, camping trips, barbeques, beach parties, community meals featuring Brazilian food, and other communal leisure activities. Before and after Sunday evening services, congregants socialise in the church foyer for quite a long time. The church usually provides coffee, soft drinks and food so that congregants can meet each other and strengthen community/family feeling. [Image at right] This is an occasion for pastors to chat with congregation members and ask them about their past week and find out their needs.

and strengthen community/family feeling. [Image at right] This is an occasion for pastors to chat with congregation members and ask them about their past week and find out their needs.

Typically, pastors assist congregation members deal with issues related to their young age, being far from their immediate family as international students in Australia, their lack of English language skills, finding accommodation and jobs, and downward mobility. CNA also helps them adapt to the new life in Australia by offering training courses in barista and cleaning skills, English language and CV writing to middle-class young Brazilian students, most of whom have never experienced paid employment in their lives.

CNA holds many activities during the year. For instance, every Friday congregants meet in smaller groups or “connect groups” across the city. These groups work as support groups to give members a solid family-feel. In these meetings, members bring food to share, socialise, and study a passage of the Bible and pray together. In addition, at the beginning of the year congregants undergo a twenty-one-day fast of some kind in order to focus on members’ behaviour in regards to God and how they are working as a church. Since 2008, they have organized a four-day camping trip over Easter. In this church retreat they have two services a day, Bible study, water baptisms, and leisure activities such as soccer games. Starting in 2012, CNA has run a three-day conference every November featuring invited pastors from Brazil. Given that CNA is mainly a church for the Brazilian community, it also celebrates typical Brazilian events such as July Party (festa caipira) in addition to Christian holidays.

LEADERSHIP/ORGANIZATION

The church is led by Senior Pastors Eduardo Ramos and Debora Oliveira, as well as AssistantPastor Jonathan Bolkenhagen. CNA’s day-to-day running is divided into “ministries” that are led by congregation members who are chosen by the pastors. These ministries are: reception of new comers, hospitality (organises food for the services and events), baby club (one to three year-olds), kids (four to seventeen year-olds), youth (eighteen to thirty year-olds), worship (the members of the band that plays during service), production (videos of services and events, publicity), and social assistance.

They also have six leaders of connect groups trained and chosen by the church leadership.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

CNA suffers from the conundrum other migrant churches face. Because they are a home away from home for Brazilians, they use Portuguese language in their services and other activities, celebrate Brazilian holidays, and espouse Brazilian religious values and worldview. However, this hinders adaptation into the local population. Furthermore, by maintaining the homeland culture, language and mores, they may alienate long-term migrants, second generation Brazilians, and those migrants who want to “integrate” quickly. At the same time, if they adopt the host country’s culture language and cultural practices wholesale, they may not be able to provide adequate support for new arrivals.

CNA Pastors are keenly aware of this problem and have organized for services to be simultaneously translated into English for those Australians who wish to join them. They know that, as young congregants marry (other Brazilians and also Australians) and have children, CNA will need to have activities in English if it wants to retain this new generation.

Another challenge is the high turnover rates within the congregation given that members are international students in Australia. Because there is always a high proportion of members arriving in the country and leaving for the homeland, it is difficult to build a strong congregation and maintain the smooth operation of the church. This also means that the church struggles with funding. As students, members do not hold full-time jobs and have low incomes. In addition, sometimes the church assists students with money, accommodation and meals if they run into financial difficulties. Another consequence of the make-up of the congregation and their low income is that pastors work full-time outside the church and have little time to work for the church.

IMAGES

Image #1: Photograph of Eduardo Ramos.

Image #2: Photograph of a worship band.

Image #3: Photograph of Jonathan Bolkenhagen.

Image #4: Photograph of a connect-group meeting.

Image #5: Photograph of serving food after a worship service.

Image #6: Reproduction of the CNA logo.

REFERENCES

Connell, John. 2005. “Hillsong: A Mega-Church in the Sydney Suburbs.” Australian Geographer 36:315-32.

Goh, Robbie. 2007. “Hillsong and ‘Megachurch’ Practice.” Material Religion 4:284-305.

Miller, Donald. 1997. Reinventing American Protestantism: Christianity in the New Millennium. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Miller, Donald and Tetsunao Yamamori. 2007. Global Pentecostalism: The New Face of Christian Social Engagement. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Riches, T. and T. Wagner, eds. 2017. The Hillsong Movement Examined: You Call Me Out Upon the Waters. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rocha, Cristina. 2017. “The Come to Brazil Effect: Young Brazilians’ Fascination with Hillsong.” In The Hillsong Movement Examined: You Call Me out upon the Waters, edited by T. Riches and T. Wagner. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rocha, Cristina. 2013. “Transnational Pentecostal Connections: an Australian Megachurch and a Brazilian Church in Australia.” Pentecostudies 12:62-82.

Rocha, Cristina. 2006. “Two Faces of God: Religion and Social Class in the Brazilian Diaspora in Sydney.” Pp. 147-60 in Religious Pluralism in the Diaspora, edited by P. Patrap Kumar. Leiden: Brill.

Sargeant, Kimon. 2000. Seeker Churches: Promoting Traditional Religion in a Nontraditional Way. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Wagner, Thomas. 2013. Hearing the Hillsong Sound: Music, Marketing, Meaning and Branded Spiritual Experience at a Transnational Megachurch. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Royal Holloway University of London.

Post Date:

2 May 2017

In August 1994, an image of the Virgin Mary, holding the baby Jesus, seemed to appear through plasterwork on a wall at the front of the church to the right of the altar. A parishioner first noticed the image and eventually commented on it to the rector at that time, Father Andrew Notere (originally Nutter), a native of Canada whose father was an Anglican archbishop (Lloyd 1996a:3). There was a waiting period to see if the image remained, and when it did, it was discussed at a church council. The Australian media took up an article that had been prepared for the local diocesan paper by Father Notere (Morgan 2007:32).

In August 1994, an image of the Virgin Mary, holding the baby Jesus, seemed to appear through plasterwork on a wall at the front of the church to the right of the altar. A parishioner first noticed the image and eventually commented on it to the rector at that time, Father Andrew Notere (originally Nutter), a native of Canada whose father was an Anglican archbishop (Lloyd 1996a:3). There was a waiting period to see if the image remained, and when it did, it was discussed at a church council. The Australian media took up an article that had been prepared for the local diocesan paper by Father Notere (Morgan 2007:32). third person, possibly Mary Magdalene or Mary MacKillop was emerging” (Pengelley 1996:3). Saint Mary MacKillop [1842-1909], the first Australian saint [cannonised 2010], was a member of the Josephite order that established a school at Yankalilla.

third person, possibly Mary Magdalene or Mary MacKillop was emerging” (Pengelley 1996:3). Saint Mary MacKillop [1842-1909], the first Australian saint [cannonised 2010], was a member of the Josephite order that established a school at Yankalilla. continued to the present day. Many common Marian pilgrimage motifs are present such as miraculous events, healing and messages. This traditional, high Anglican church has accepted the image in its Church despite the general “Protestant view [which] tends to limit the communion of saints to the living and does not look favourably on the possibility of supernatural intervention by deceased saints” (Turner and Turner 1982:145). At the Shrine of Our Lady of Yankalilla visitors have the chance to observe, and to have experiences, that they do not have in their home parishes. Interestingly, the initial rituals at the shrine were drawn from Charismatic, Catholic, Anglican and Buddhist practices (Jones 1998). These rather New Age practices could attract visitors who may not necessarily be drawn to an Anglican church (Cusack 2003:119). McPhillips considers such a mix “in effect releases Mary into new realms of enchantment” (McPhillips 2006:149). It did however cause conflict at a parish level (Jones 1998).

continued to the present day. Many common Marian pilgrimage motifs are present such as miraculous events, healing and messages. This traditional, high Anglican church has accepted the image in its Church despite the general “Protestant view [which] tends to limit the communion of saints to the living and does not look favourably on the possibility of supernatural intervention by deceased saints” (Turner and Turner 1982:145). At the Shrine of Our Lady of Yankalilla visitors have the chance to observe, and to have experiences, that they do not have in their home parishes. Interestingly, the initial rituals at the shrine were drawn from Charismatic, Catholic, Anglican and Buddhist practices (Jones 1998). These rather New Age practices could attract visitors who may not necessarily be drawn to an Anglican church (Cusack 2003:119). McPhillips considers such a mix “in effect releases Mary into new realms of enchantment” (McPhillips 2006:149). It did however cause conflict at a parish level (Jones 1998). visitors originating from India, most notably from Kerala and Goa, while others are from the South Australian Indian community (Gardiner 2015). The visitors’ book indicates pilgrims are local, interstate as well as from Europe, South America and Asia. These visits may just be curiosity; however, “a tourist is half a pilgrim, if a pilgrim is half a tourist” (Turner 1978;20)

visitors originating from India, most notably from Kerala and Goa, while others are from the South Australian Indian community (Gardiner 2015). The visitors’ book indicates pilgrims are local, interstate as well as from Europe, South America and Asia. These visits may just be curiosity; however, “a tourist is half a pilgrim, if a pilgrim is half a tourist” (Turner 1978;20) international shrine” (Smart 1996:6 Innes 1996:4). This blessing would appear to indicate that at the time of the emergence of the image there was official Anglican support and acceptance. It is important for miraculous events to fall within the boundaries of the traditional religion with which it is associated. T he Virgin Mary can be found in Anglican shrines, such as at Walsingham [United Kingdom], a site visited by many pilgrims each year, and Christ Church Yankalilla is high Anglican, which accepts veneration of the Virgin Mary (Kahl 1998:257). To link these shrines, an icon dedicated to Walsingham hangs on the Church wall. Such an icon, a pieta (a statue depicting the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus) image, may assist visitors in seeing the apparent image on the wall (Morgan 2007:31).

international shrine” (Smart 1996:6 Innes 1996:4). This blessing would appear to indicate that at the time of the emergence of the image there was official Anglican support and acceptance. It is important for miraculous events to fall within the boundaries of the traditional religion with which it is associated. T he Virgin Mary can be found in Anglican shrines, such as at Walsingham [United Kingdom], a site visited by many pilgrims each year, and Christ Church Yankalilla is high Anglican, which accepts veneration of the Virgin Mary (Kahl 1998:257). To link these shrines, an icon dedicated to Walsingham hangs on the Church wall. Such an icon, a pieta (a statue depicting the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus) image, may assist visitors in seeing the apparent image on the wall (Morgan 2007:31). was formed but since disbanded. The aims of the community were to work with pilgrims and foster a healing spirit at the shrine (Kahl 1998:50). A Retreat Centre next to the church was established in 2000, but the space is now utilized for general parish purposes (Morgan 2007:33). A Maori group of singers was reportedly considering moving to the area, drawn by the image. The group joined a local choir to make a CD dedicated to the Virgin Mary appearing at Yankalilla (“Choirs Combine” 2002:14).

was formed but since disbanded. The aims of the community were to work with pilgrims and foster a healing spirit at the shrine (Kahl 1998:50). A Retreat Centre next to the church was established in 2000, but the space is now utilized for general parish purposes (Morgan 2007:33). A Maori group of singers was reportedly considering moving to the area, drawn by the image. The group joined a local choir to make a CD dedicated to the Virgin Mary appearing at Yankalilla (“Choirs Combine” 2002:14). Sydney in 1978 to join Frank Houston, who had founded the Christian Life Centre there the year before. Brian, together with Bobbie, planted the Hills Christian Life Centre in 1983 from Frank’s original church. The church started out of the Houston’s Sunday night outreach program and was not an immediate success. Houston explained: “the very first Sunday we had 70 people turn up. The second week, there were 60, the third week, 53, and by the fourth week, 45. I’ve often joked that we worked it out at the time- we had only four and a half weeks left until there were no more people. It was about that time that we had our first ever commitment to Christ. We outgrew the school hall after twelve months. The crowds were so big that we were using road-case as the platform, and what should have been the stage as a balcony so that we could fit more people in” (Houston 2014).

Sydney in 1978 to join Frank Houston, who had founded the Christian Life Centre there the year before. Brian, together with Bobbie, planted the Hills Christian Life Centre in 1983 from Frank’s original church. The church started out of the Houston’s Sunday night outreach program and was not an immediate success. Houston explained: “the very first Sunday we had 70 people turn up. The second week, there were 60, the third week, 53, and by the fourth week, 45. I’ve often joked that we worked it out at the time- we had only four and a half weeks left until there were no more people. It was about that time that we had our first ever commitment to Christ. We outgrew the school hall after twelve months. The crowds were so big that we were using road-case as the platform, and what should have been the stage as a balcony so that we could fit more people in” (Houston 2014). in New Zealand (Morton and Box 2014). Brian oversaw his father’s removal from the church, and he and Bobbie took over leadership of the original Sydney Christian Life Centre. The Houstons rebranded this family of churches simply as “Hillsong,” in recognition both of the Hills district where the church had experienced such tremendous growth, and the music that played such an important part in worship and services. Having continued to grow in number, Hillsong built a large conference venue, the Hillsong Convention Centre, in Baulkham Hills. Then Australian Prime Minister, John Howard, opened the centre in 2002.

in New Zealand (Morton and Box 2014). Brian oversaw his father’s removal from the church, and he and Bobbie took over leadership of the original Sydney Christian Life Centre. The Houstons rebranded this family of churches simply as “Hillsong,” in recognition both of the Hills district where the church had experienced such tremendous growth, and the music that played such an important part in worship and services. Having continued to grow in number, Hillsong built a large conference venue, the Hillsong Convention Centre, in Baulkham Hills. Then Australian Prime Minister, John Howard, opened the centre in 2002. Build Great Relationships; How to Flourish in Life; How to Make Wise Choices; and How to Live in Health and Wholeness (Houston 2013) . These five books were published together as How to Maximise Your Life after the earlier publication of the work, You Need More Money: Discover God’s Amazing Financial Plan (1999) was lambasted by the press for its title. In the book, Houston argued that “God actually gets pleasure when we prosper” financially, because “money answers everything” (Houston 1999:2, 20). To Houston, faith can lead to prosperity and an individual’s faith is tangible and reflected in their health and wealth. He describes this attitude to wealth, which is often labelled as embodying the “prosperity gospel,”as “prosperity for a purpose” or “prosperity on purpose” (Houston 2008: 123). This has become one of the central tenets of Houston’s preaching and Hillsong’s message (Houston quoted in Marriner 2009).

Build Great Relationships; How to Flourish in Life; How to Make Wise Choices; and How to Live in Health and Wholeness (Houston 2013) . These five books were published together as How to Maximise Your Life after the earlier publication of the work, You Need More Money: Discover God’s Amazing Financial Plan (1999) was lambasted by the press for its title. In the book, Houston argued that “God actually gets pleasure when we prosper” financially, because “money answers everything” (Houston 1999:2, 20). To Houston, faith can lead to prosperity and an individual’s faith is tangible and reflected in their health and wealth. He describes this attitude to wealth, which is often labelled as embodying the “prosperity gospel,”as “prosperity for a purpose” or “prosperity on purpose” (Houston 2008: 123). This has become one of the central tenets of Houston’s preaching and Hillsong’s message (Houston quoted in Marriner 2009). Lord and build a close, personal relationship with him (Houston 2013). Ben Fielding, one of Hillsong’s music/creative leaders says that “music reflects the creativity and beauty of God; its ultimate purpose is to bring enjoyment and cause us to draw near to our Creator” (Fielding 2012). Hillsong released its first tape of worship music, Spirit and Truth, in 1988, though the church had had a music pastor (Geoff Bullock) since 1985. Darlene Zschech replaced Bullock in 1994, and remained the church’s worship pastor until 2007. Zschech is probably the best-known Hillsong worship leader and was instrumental in increasing the popularity of Hillsong’s music, with 35,000,000 Christians around the world sing one of her most popular songs, Shout to the Lord, at church each week (Houston 2005).

Lord and build a close, personal relationship with him (Houston 2013). Ben Fielding, one of Hillsong’s music/creative leaders says that “music reflects the creativity and beauty of God; its ultimate purpose is to bring enjoyment and cause us to draw near to our Creator” (Fielding 2012). Hillsong released its first tape of worship music, Spirit and Truth, in 1988, though the church had had a music pastor (Geoff Bullock) since 1985. Darlene Zschech replaced Bullock in 1994, and remained the church’s worship pastor until 2007. Zschech is probably the best-known Hillsong worship leader and was instrumental in increasing the popularity of Hillsong’s music, with 35,000,000 Christians around the world sing one of her most popular songs, Shout to the Lord, at church each week (Houston 2005). 250,000 adherents around the country. Hillsong, like the AOG/Australian Christian Churches, embraces apostolic leadership, or “leadership by God appointed apostolic ministries” (Cartledge 2000). Brian Houston argues that Hillsong represents a “network that connects hundreds and thousands of pastors…committed to the apostolic anointing of leaders” (Houston, “The Church I Now See,” 2014).

250,000 adherents around the country. Hillsong, like the AOG/Australian Christian Churches, embraces apostolic leadership, or “leadership by God appointed apostolic ministries” (Cartledge 2000). Brian Houston argues that Hillsong represents a “network that connects hundreds and thousands of pastors…committed to the apostolic anointing of leaders” (Houston, “The Church I Now See,” 2014). Church Australia’s 2013 Annual Report, the total revenue generated by the College is $8,155,639 (Hillsong 2013 Annual Report:18). Students can study Pastoral Leadership, Worship Music, TV & Media, Dance, Production, or can undertake a Bachelor of Theology, offered in conjunction with Alphacrucis College. Attendees spend part of their time at College doing “Fieldwork,” where students “get the opportunity to serve in church life” (“What Makes Hillsong College Different?” 2014). Hillsong College also runs shorter evening courses on a variety of topics including money, relationships, and parenting (“Evening College Life Courses” 2015).

Church Australia’s 2013 Annual Report, the total revenue generated by the College is $8,155,639 (Hillsong 2013 Annual Report:18). Students can study Pastoral Leadership, Worship Music, TV & Media, Dance, Production, or can undertake a Bachelor of Theology, offered in conjunction with Alphacrucis College. Attendees spend part of their time at College doing “Fieldwork,” where students “get the opportunity to serve in church life” (“What Makes Hillsong College Different?” 2014). Hillsong College also runs shorter evening courses on a variety of topics including money, relationships, and parenting (“Evening College Life Courses” 2015). openly acknowledges that his book, You Need More Money, was poorly received. He said: “ If you said to me ‘what are the three silliest things you’ve done’, that would probably be No. 1. The heart of the book was never just being greedy and selfish …I put a bullseye on my head” (Marriner 2009). In a 2005 interview explaining this public attitude towards Hillsong, Houston said, “Hillsong church today has facilities valued somewhere near $100 million. In our last accounting period, the total income was fifty million dollars. I think that the idea of a church being big and successful and effective threatens some people” (Houston 2005). Tanya Riches, who grew up attending Hillsong and is now postgraduate student studying the church, believes that the Australian media “doesn’t get Hillsong” and sees it as “money hungry, a sham, flamboyant, corrupt” (Riches 2014). One journalist described Hillsong’s marriage of faith and finance as “Praise the Lord and pass the chequebook” (Beaurup 2005).

openly acknowledges that his book, You Need More Money, was poorly received. He said: “ If you said to me ‘what are the three silliest things you’ve done’, that would probably be No. 1. The heart of the book was never just being greedy and selfish …I put a bullseye on my head” (Marriner 2009). In a 2005 interview explaining this public attitude towards Hillsong, Houston said, “Hillsong church today has facilities valued somewhere near $100 million. In our last accounting period, the total income was fifty million dollars. I think that the idea of a church being big and successful and effective threatens some people” (Houston 2005). Tanya Riches, who grew up attending Hillsong and is now postgraduate student studying the church, believes that the Australian media “doesn’t get Hillsong” and sees it as “money hungry, a sham, flamboyant, corrupt” (Riches 2014). One journalist described Hillsong’s marriage of faith and finance as “Praise the Lord and pass the chequebook” (Beaurup 2005). retention rates at Hillsong are so low. That is, people are looking for a more personal connection with a pastor and the congregation than is possible when you are one of thousands worshiping at a service. More than this, as a megachurch, Hillsong has become a large institution that caters for more than religious needs. It embraces modernity and makes faith convenient through the live online streaming of church services, the provision of food and drink outlets in church foyers, the ability to make donations using EFTPOS facilities, and the increasing use of social media platforms to release information and content. Hillsong has since been criticised by various social commentators for producing a form of religion that is “light” on theology and very broad. Some argue that the church is more focused on giving attendants an enjoyable worship experience, than on Bible teaching (Pulliam Bailey 2013; Marr 2007). However, some argue that being a megachurch has helped Hillsong’s popularity because people today are comfortable in large institutions associated with market success (Connell 2005:317).

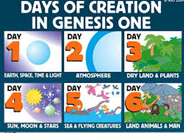

retention rates at Hillsong are so low. That is, people are looking for a more personal connection with a pastor and the congregation than is possible when you are one of thousands worshiping at a service. More than this, as a megachurch, Hillsong has become a large institution that caters for more than religious needs. It embraces modernity and makes faith convenient through the live online streaming of church services, the provision of food and drink outlets in church foyers, the ability to make donations using EFTPOS facilities, and the increasing use of social media platforms to release information and content. Hillsong has since been criticised by various social commentators for producing a form of religion that is “light” on theology and very broad. Some argue that the church is more focused on giving attendants an enjoyable worship experience, than on Bible teaching (Pulliam Bailey 2013; Marr 2007). However, some argue that being a megachurch has helped Hillsong’s popularity because people today are comfortable in large institutions associated with market success (Connell 2005:317). with creationism, in part due to the struggles over a variety of issues (e.g., science education, sex education, prayer in schools) in the public school system. One outgrowth of these struggles has been the formation of a variety of museums, research institutes, and foundations defending the biblical creation narrative (Numbers 2006; Duncan 2009). Creationist museums are found primarily in the United States, but there is a sprinkling of such museums around the world (Simitopoulou and Xirotitis 2010). The most prominent creationist museums in the U.S. was established by Answers in Genesis.

with creationism, in part due to the struggles over a variety of issues (e.g., science education, sex education, prayer in schools) in the public school system. One outgrowth of these struggles has been the formation of a variety of museums, research institutes, and foundations defending the biblical creation narrative (Numbers 2006; Duncan 2009). Creationist museums are found primarily in the United States, but there is a sprinkling of such museums around the world (Simitopoulou and Xirotitis 2010). The most prominent creationist museums in the U.S. was established by Answers in Genesis. CSF board in Australia sent Ham to work with Dr. Henry Morris’s Institute for Creation Research (ICR) in 1987 as a speaker; he remained the Director of the Australian CSF ministry until 2004. Ham went on to lecture not only in the U.S. but also in the U.K.

CSF board in Australia sent Ham to work with Dr. Henry Morris’s Institute for Creation Research (ICR) in 1987 as a speaker; he remained the Director of the Australian CSF ministry until 2004. Ham went on to lecture not only in the U.S. but also in the U.K. creationists, attempt to validate biblical dating and the biblical creation narrative. Answers in Genesis (AIG) can be categorized as Young-Earth Creationists (YECs). AIG asserts that the Bible is the word of God and the absolute authority on all matters. The Board of AIG explains that any evidence in any area of knowlege must be confirmed by the Bible to be valid. As AIG puts the matter, “no apparent, perceived or claimed evidence in any field, including history and chronology, can be valid if it contradicts the scriptural record” (Answers in Genesis 2012). Therefore, AIG accepts the Bible as the accurate historical account of Earth’s creation recorded in Genesis 3:14-19 (Ross, 2005). From its perspective, the organization of the natural world is “irreducibly complex” and could only have been originally designed (Petto & Godfrey, 2007).

creationists, attempt to validate biblical dating and the biblical creation narrative. Answers in Genesis (AIG) can be categorized as Young-Earth Creationists (YECs). AIG asserts that the Bible is the word of God and the absolute authority on all matters. The Board of AIG explains that any evidence in any area of knowlege must be confirmed by the Bible to be valid. As AIG puts the matter, “no apparent, perceived or claimed evidence in any field, including history and chronology, can be valid if it contradicts the scriptural record” (Answers in Genesis 2012). Therefore, AIG accepts the Bible as the accurate historical account of Earth’s creation recorded in Genesis 3:14-19 (Ross, 2005). From its perspective, the organization of the natural world is “irreducibly complex” and could only have been originally designed (Petto & Godfrey, 2007). their creation museum. Two efforts to rezone land for the project met strong opposition from evolution proponents and other secular groups. Despite this resistance, hundreds of radio stations began featuring AIG’s Answers program. By 2006, AIG’s website, AnswersInGenesis.org, was chosen out of 1,300 ministries to receive the “Website of the Year” award from the National Religious Broadcasters. The website has gone on to host about 25,000 visitors a day. The AIG magazine, Creation, which was originally published in Australia, is also distributed in the United States. In 2006, however, AIG-US discovered that over half their subscribers did not renew their subscriptions after one year. The organization recognized the need for a new magazine, Answers , which would feature biblical and scientific articles about the origins controversy and emphasize the biblical worldview with practical applications. Further differences between the American and Australian branches caused AIG-US to stop distributing Creation and focus solely on Answers. After only five years in operation, Answers received the “Award of Excellence” from the Evangelical Press Association (Ham n.d.).

their creation museum. Two efforts to rezone land for the project met strong opposition from evolution proponents and other secular groups. Despite this resistance, hundreds of radio stations began featuring AIG’s Answers program. By 2006, AIG’s website, AnswersInGenesis.org, was chosen out of 1,300 ministries to receive the “Website of the Year” award from the National Religious Broadcasters. The website has gone on to host about 25,000 visitors a day. The AIG magazine, Creation, which was originally published in Australia, is also distributed in the United States. In 2006, however, AIG-US discovered that over half their subscribers did not renew their subscriptions after one year. The organization recognized the need for a new magazine, Answers , which would feature biblical and scientific articles about the origins controversy and emphasize the biblical worldview with practical applications. Further differences between the American and Australian branches caused AIG-US to stop distributing Creation and focus solely on Answers. After only five years in operation, Answers received the “Award of Excellence” from the Evangelical Press Association (Ham n.d.). 2007. Ham created the Creation Museum to spread “Biblically correct science” to the public and to try and bring Creationism into the mainstream. He preferred a museum to a church because museums are accepted as places of public education and for the display of scientific research findings. Further, a museum is a more engaging environment in which to encourage learning among children. Finally, a museum could connect directly with visitors and AIG’s message would not be filtered through mainstream scientists or the government (Duncan 2009). According to Ham, AIG simply wants the Creation Museum to tell people that “the Bible is true and the Bible is God’s word, that’s what it’s all about” (Jacoby, 1998). The museum features a planetarium, the Johnson Observatory, SFX Theater, a petting zoo, an insectarium, a zip-line course, dinosaur fossils, and animatronic exhibits. The Creation Museum was very successful in its first year, attracting 404,000 visitors but suffered declining visitation, with only 280,000 visitors in 2012.

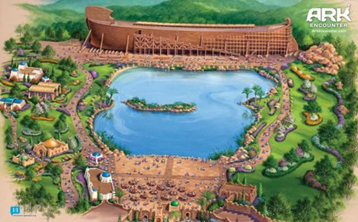

2007. Ham created the Creation Museum to spread “Biblically correct science” to the public and to try and bring Creationism into the mainstream. He preferred a museum to a church because museums are accepted as places of public education and for the display of scientific research findings. Further, a museum is a more engaging environment in which to encourage learning among children. Finally, a museum could connect directly with visitors and AIG’s message would not be filtered through mainstream scientists or the government (Duncan 2009). According to Ham, AIG simply wants the Creation Museum to tell people that “the Bible is true and the Bible is God’s word, that’s what it’s all about” (Jacoby, 1998). The museum features a planetarium, the Johnson Observatory, SFX Theater, a petting zoo, an insectarium, a zip-line course, dinosaur fossils, and animatronic exhibits. The Creation Museum was very successful in its first year, attracting 404,000 visitors but suffered declining visitation, with only 280,000 visitors in 2012. located on 800 acres near Interstate 75 in Grant County, Kentucky and is scheduled to open in the summer of 2016 (Ham, n.d.). The Ark Encounter is described as “a 160-acre park with a life-size replica of Noah’s Ark built to stand 500 feet long and 80 feet high” (Goodwin 2012). Initial construction plans were delayed until 2014 due to a weak economy and a decline in visitation to the Creation Museum (Goodwin 2012). Based on outside consulting term estimates, AIG has anticipated 1,600,000 visitors in its first year, as well as improved visitation. The initial financial projections were also optimistic as a result of tax breaks pledged by the State of Kentucky; these were withdrawn after considerable controversy concerning church-state separation (Alford 2010; “Kentucky” 2015). AIG subsequently announced plans to sue Kentucky over the withdrawal (Linshi 2015).

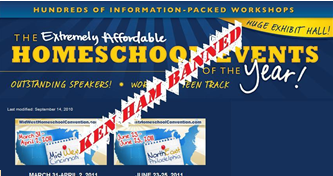

located on 800 acres near Interstate 75 in Grant County, Kentucky and is scheduled to open in the summer of 2016 (Ham, n.d.). The Ark Encounter is described as “a 160-acre park with a life-size replica of Noah’s Ark built to stand 500 feet long and 80 feet high” (Goodwin 2012). Initial construction plans were delayed until 2014 due to a weak economy and a decline in visitation to the Creation Museum (Goodwin 2012). Based on outside consulting term estimates, AIG has anticipated 1,600,000 visitors in its first year, as well as improved visitation. The initial financial projections were also optimistic as a result of tax breaks pledged by the State of Kentucky; these were withdrawn after considerable controversy concerning church-state separation (Alford 2010; “Kentucky” 2015). AIG subsequently announced plans to sue Kentucky over the withdrawal (Linshi 2015). Homeschool Conventions, Inc. (GHC) voted to disinvite Ken Ham and AIG from “all future conventions [as Ham made] unnecessary, ungodly, and mean-spirited statements that are divisive at best and defamatory at worst” (Blackford 2011) about another speaker at the convention. The board stated that “Ken’s public criticism of the convention itself and other speakers at [the] convention require him to surrender spiritual privilege of addressing a homeschool audience” (Blackford 2011). Ham, in his blog, explained that Peter Enns of the BioLogos Foundation teaches misleading information about Genesis that compromises Genesis with evolution and is an “outright liberal theology that totally undermines the authority of the Word of God” (Answers in Genesis Board of Directors 2011). After the allegations against Ham being un-Christian and sinful were made, AIG launched an internal investigation of GHC, but has yet to find any resolution (Answers in Genesis Board of Directors 2011).

Homeschool Conventions, Inc. (GHC) voted to disinvite Ken Ham and AIG from “all future conventions [as Ham made] unnecessary, ungodly, and mean-spirited statements that are divisive at best and defamatory at worst” (Blackford 2011) about another speaker at the convention. The board stated that “Ken’s public criticism of the convention itself and other speakers at [the] convention require him to surrender spiritual privilege of addressing a homeschool audience” (Blackford 2011). Ham, in his blog, explained that Peter Enns of the BioLogos Foundation teaches misleading information about Genesis that compromises Genesis with evolution and is an “outright liberal theology that totally undermines the authority of the Word of God” (Answers in Genesis Board of Directors 2011). After the allegations against Ham being un-Christian and sinful were made, AIG launched an internal investigation of GHC, but has yet to find any resolution (Answers in Genesis Board of Directors 2011). He stated that “If we raise a generation of students who don’t believe in the process of science, who think everything that we’ve come to know about nature and the universe can be dismissed by a few sentences translated into English from some ancient text, you’re not going to continue to innovate” (Lovan 2012). For his part, Ham attempted to substantiate the YEC model of the universe’s origins. He reasserted that Earth was created by God approximately 6,000 years ago and dinosaurs and humans once coexisted, as it is specifically stated in the Genesis. Nye sought to refute Ham’s claims by citing widely supported observations by scientists that the Earth is approximately 4.5 billion years old. Ham responded that “I believe science has been hijacked by secularists…and that there is a difference between historical science and observational science” (“Bill Nye Debates Ken Ham” 2014). Nye pointed out that a variety of methodologies (radiometric dating, ice core data, and the light from distant stars) supports the position that the Earth is much older than 6,000 years (Lovan 2012). When Ham referred to the Genesis flood narrative and Noah’s Ark, Nye pointed out that the Ark as described in the Book of Genesis would not float. Nye also pointed out that, using Nye’s calculations, an ark containing 7,000 kinds of animals would require that approximately eleven new species would have to come into existence every day for the Earth to contain all presently known species (O’Neil 2014). While Ham does not have appeared to have won over a majority of the audience, he seemed unconcerned. From his perspective, the publicity generated by the debate was a source of fundraising for AIG’s construction of the Ark Encounter theme park (Chowdhury 2014).

He stated that “If we raise a generation of students who don’t believe in the process of science, who think everything that we’ve come to know about nature and the universe can be dismissed by a few sentences translated into English from some ancient text, you’re not going to continue to innovate” (Lovan 2012). For his part, Ham attempted to substantiate the YEC model of the universe’s origins. He reasserted that Earth was created by God approximately 6,000 years ago and dinosaurs and humans once coexisted, as it is specifically stated in the Genesis. Nye sought to refute Ham’s claims by citing widely supported observations by scientists that the Earth is approximately 4.5 billion years old. Ham responded that “I believe science has been hijacked by secularists…and that there is a difference between historical science and observational science” (“Bill Nye Debates Ken Ham” 2014). Nye pointed out that a variety of methodologies (radiometric dating, ice core data, and the light from distant stars) supports the position that the Earth is much older than 6,000 years (Lovan 2012). When Ham referred to the Genesis flood narrative and Noah’s Ark, Nye pointed out that the Ark as described in the Book of Genesis would not float. Nye also pointed out that, using Nye’s calculations, an ark containing 7,000 kinds of animals would require that approximately eleven new species would have to come into existence every day for the Earth to contain all presently known species (O’Neil 2014). While Ham does not have appeared to have won over a majority of the audience, he seemed unconcerned. From his perspective, the publicity generated by the debate was a source of fundraising for AIG’s construction of the Ark Encounter theme park (Chowdhury 2014).