EVELYN UNDERHILL TIMELLINE

1875 (December 6): Evelyn Underhill was born in Wolverhampton, England.

1888–1891: Underhill attended Sandgate House boarding school in Folkestone.

1891: Underhill was confirmed in Anglican Church.

1897–1898: Underhill attended King’s College, University of London, and began a period of atheism.

1898: Underhill made her first trip to Italy.

1904: Underhill’s first novel, The Grey World, was published. Her vocation as a spiritual director began. She met Ethel Ross Barker, who was to become her best friend.

1907: Underhill had a conversion experience at Southampton. Her second novel, The Lost Word, was published. She married Hubert Stuart Moore in July.

1909: Underhill’s third novel, The Column of Dust, was published.

1911: Mysticism: The Path of Eternal Wisdom was published under the pseudonym of John Cordelier.

1912: Immanence: Book of Verses was published. The Spiral Way was published under the pseudonym of John Cordelier.

1913: The Mystic Way: A Psychological Study in Christian Origins was published.

1914: Practical Mysticism was published.

1915: Mysticism and War was published. Theophanies: A Book of Verses was published.

1919: A study of Jacopone da Todi: Poet and Mystic (c. 1230–1306) was published.

1920: The Essentials of Mysticism and Other Essays was published. Underhill’s best friend Ethel Ross Barker died. Underhill returned to the Anglican Church.

1921: Baron Friedrich von Hugel became Underhill’s spiritual director. She delivered the first of the Upton Lectures, becoming the first woman to have her name on the Oxford University list. The lectures were published as The Life of the Spirit and the Life of Today.

1922: Underhill attended her first retreat at Pleshey Retreat House.

1924: Underhill conducted her first retreat at Pleshey Retreat House.

1925: Mystics of the Church was published.

1926: Concerning the Inner Life was published.

1927: Man and the Supernatural was published.

1929: The House of the Soul was published. Underhill became religion editor of The Spectator, a position she held until 1932.

1932: The Golden Sequence: A Fourfold Study of the Spiritual Life was published. Reginald Somerset Ward became her Spiritual Director.

1933: Mixed Pasture: Twelve Essays and Addresses was published.

1934: The School of Charity: Meditations on the Christian Creed was published.

1936: Worship was published.

1937: The Spiritual Life, consisting of four radio broadcasts given for the BBC in 1936, was published.

1938: The Mystery of Sacrifice: A Meditation on the Liturgy was published. Underhill was awarded an Honorary Doctorate (DD) from the University of Aberdeen, but was too ill to receive it in person.

1939: Publications this year included: Eucharistic Prayers from the Ancient Liturgies; A Meditation on Peace; Prayer in Wartime; A Service of Prayer for Use in Wartime; Spiritual Life in Wartime.

1940: Abba: Meditations on the Lord’s Prayer and The Church and War were published.

1941 (June 15): Underhill’s last review was published in Time and Tide. She died at Lawn House, Hampstead, and was buried from Christ Church in the graveyard of St. John’s Parish Church, Hampstead.

BIOGRAPHY

Sometimes referred to as “a modern mystic,” Evelyn Underhill (1875–1941) offered twentieth-century seekers and people of faith a way to reclaim and live the life of prayer and contemplation that is described and modeled by the great mystics of the Christian tradition. [Image at right] Her writings, letters of direction, and retreat addresses offer practical, accessible advice about the spiritual life. spoke with authority to clergy and religious leaders, a woman leading in a patriarchal church, she continues through her writings to inspire those who seek to integrate a grounded spiritual life with faithful, sacrificial service to a world they believe is in need of healing.

An overview of Evelyn Underhill’s life sorts itself into three important periods: the time before and during the Great War (1900–1914); the postwar period (1921–1934) when she began to claim a specifically Christian path and became well known as a retreat leader and writer on religion, especially in Anglican spaces; and the period from the mid-1930s to her death in 1941, during which she sought to reach a wider and more ecumenical audience through the writing of Worship (1936) and the radio addresses published as The Spiritual Life (1937). As the Second World War (1939–1945) loomed and broke out, she led a prayer group and became a courageous and outspoken proponent of Christian pacifism before her death on June 15, 1941.

Between 1890 and 1914 Evelyn Underhill began her spiritual explorations. Her earliest writings include three novels, The Gray World (1904), The Lost Word (1907), and A Column of Dust (1909). These novels create worlds in which a spiritual realm is vividly present in ordinary life, but without theological commitment to a personal God. [Image at right] Underhill at this time was interested in the popular spiritualities, including magic and occultism, that permeated English culture before the Great War. She was drawn to mystical writers of many traditions, for example, writing an extensive introduction to Rabrindranath Tagore’s translations of Kabir (Tagore 1915:v-xliv). She was a member of the Hermetic Society of the Golden Dawn from 1902–1906. But she became increasingly drawn to Roman Catholic practice, especially through the influence of her friend Ethel Barker, a fellow seeker and Catholic convert whom she met in 1904.

A mystical experience in 1907, while she was on retreat with Ethel Barker, left Underhill awestruck and “converted” to a conviction of the truth of Roman Catholic teaching (Cropper 1958:29). Largely self-educated in the Christian mystics and the Christian spiritual path, she may well have turned to study of the mystics in order to make sense of her own experience, researching and writing what became her best known work, Mysticism: A Study in the Nature and Development of Man’s Spiritual Consciousness. First published in 1911, Mysticism went through twelve printings between 1911 and 1931, with some new prefaces reflecting the evolution of Underhill’s thought even without changes to the basic text of the book. It has remained continuously in print since its initial publication.

As the First World War was breaking out, Underhill published Practical Mysticism, in some editions subtitled A Little Book for Normal People. Defining mysticism simply as “the art of union with Reality” (Underhill 1915:23), the book is a primer for “the practical man” (1915:35) on different stages of contemplation, drawn from the Christian mystical tradition but expressed in broad and nondoctrinal terms. The movement through these stages can lead the “ordinary man” to an experience of divine Reality which is not simply an end in itself, but is rather the nourishment that souls need in order to go out and serve a world in need.

Even before the war, Underhill began responding by letter to requests for spiritual direction. Her advice was tailored to particular spiritual directees and always down-to-earth and practical. She was skeptical of excessive effort to “achieve” dramatic spiritual experiences, and encouraged people toward growth in compassion and charity. Her letters include one from 1904 to her first correspondent, Margaret Robinson (M.R.), who writes to her admiring The Grey World. Underhill responded:

when once it has happened to you to perceive that beauty is “the outward and visible sign” of the greatest of sacraments, I don’t think you can ever again get hopelessly entangled by its merely visible side. . . . Perhaps you will write to me again when you are in the mood. . . . Those who are on the same road can sometimes help each other (Williams 1943:51).

Her letters of direction, published in 1943 in an edition by Charles Williams, and further edited and expanded by Carol Poston in The Making of a Mystic (2010), remain a rich resource for understanding Underhill’s particular voice and wisdom as a spiritual guide.

This early period also saw the publication of two volumes of poetry, Immanence (1912) and Theophanies (1916). Though most of her poetry tended toward the rhymed, conventional verse of her Edwardian literary period, the title poem of Immanence continues to be quoted often and expresses well the incarnational theology that was beginning to appeal to Underhill (1912:1):

I come in the little things,

Saith the Lord

Not borne on morning wings

Of majesty, but I have set my feet

Amidst the delicate and bladed wheat

That springs triumphant in the furrowed seed.

There do I dwell in weakness and in power

Not broken or divided, saith our God.

Evelyn Underhill entered public ministry as a laywoman between 1921 and 1932. In her mid-forties, during and following the First World War, Underhill reflects that she “went to pieces” spiritually and emotionally, both from the stress of wartime losses and from grief at the death of her dear friend Ethel Barker in 1919 (Greene 1990:70). Though we have few details about her interior experiences at this time, we know that in 1921 she sought spiritual direction from Baron Friedrich von Hugel (1852–1925). Von Hugel was a well-known Catholic layperson and modernist, theologian and author of books on spirituality, notably The Mystical Element in Religion: A Study of St. Catherine of Genoa (1908). Writing to Underhill after her publication of Mysticism, he chided her gently for the “theocentric” rather than “Christocentric” character of her work. However, her time with the baron opened her up to the life and example of Jesus as a resource for her growth into the Christian life, and led her to a deeper experience of the spiritual reality embraced by the Christian mystics. Von Hugel was a neighbor whom she saw occasionally on walks in Kensington, but their spiritual direction relationship happened mainly by letter, one or two long letters every six months or so that she was invited to ponder and pray over. Much of their relationship seems to have been developed through prayer (Wrigley-Carr 2020:48–84).

Evelyn Underhill’s husband Hubert Stuart Moore, whom she married in 1907, did not share her religious ardor and curiosity, and it appears that his horror of her going to a confessor contributed to her decision not to become a Roman Catholic. But they had been friends from childhood, and traveled and enjoyed yachting, hiking in the Alps, and a pleasant domestic life, and he was supportive of her work and celebrated her publications. Indeed, there is some evidence that the income she earned from her writing was appreciated by her husband. In her letters, she urges correspondents to seek a balance between the intense attractions of the life of prayer and the duties of ordinary life. Her account of why she did not become a Catholic, written to a later spiritual director, gives a good sense of her homely, practical voice, together with the depth of her commitment to a vocation as spiritual leader and teacher in the Anglican Church.

The Anglican Church] seems to me to be a respectable suburb of the City of God—but all the same, part of “Greater London.” I appreciate the superior food, etc., to be had near the center of things. But the whole point to me is the fact that Our Lord has put me here, keeps on giving me more jobs to do for souls here, and has never given me orders to move. In fact, when I have been inclined to think of this, something has always stopped me, and if I did it, it would be purely an act of spiritual self-interest and self-will. . . .

Of course I know I might get other orders at any moment, but so far that is not so. After all He has lots of terribly hungry sheep in Wimbledon, and if it is my job to try and help with them a bit it is no use saying I should rather fancy a flat in Mayfair, is it? (Letter to Dom John Chapman, 9 June 1931, in Williams 1943:195–96).

Von Hugel led Underhill to engage in the “institutional element of religion,” attending church, and visiting the poor. He encouraged “moderation” in her ardent spiritual practices. Twice a week, she began visiting poor families in North Kensington, a practice that deepened her awareness of her own privilege and of class division, and led to a desire to bridge this gap. This was reflected in her important friendship with Laura Rose, a young widow who was among those she visited (Greene 1998:84–85).

Underhill remained in direction with von Hugel until his death early in 1925, a profound loss to her. He led her toward a more settled, incarnational and Christ-centered spirituality, urging her away from excessive scrupulosity and excessive ardor in the life of prayer, and counseling a trust in the resources of institutional Christianity, despite disagreement with the contemporary Catholic Church’s teachings against Modernism. (In a 1907 encyclical, Pope Pius X had condemned Modernism in Catholic teaching (that is, the effort of scholars and theologians to interpret Catholic teaching in light of historical-critical biblical studies and contemporary scientific and political developments). Gradually, under von Hugel’s influence, her focus turned away from the more academic explorations we find in Mysticism and toward the ways that mysticism’s “union with the Real” is experienced in the daily lives of ordinary Christian believers. The practicality and everyday wisdom of her mature voice owes much to her years with “my Baron,” as she called von Hugel.

Another important though little-known spiritual teacher for Underhill in this period was Sorella Maria di Campello (1875–1961), an Italian Franciscan sister whom Underhill met only once in person, on a visit to Assisi in 1925, but with whom she had a long correspondence. Through her friend Amy Turton, who was a friend and supporter of Sorella Maria’s community, Underhill had heard in 1919 of the Spiritual Entente, a loosely knit-secret fellowship of prayer that sought to unite people across faith traditions in prayers for peace and unity in the human spiritual life (Allchin 2003). She was drawn to the Entente’s ecumenicity and its commitment to intercessory prayer as having real, though invisible, influence in the world. New to her was the expectation that members of the Entente would be associated with a worshipping community. This, along with von Hugel’s counsel, may be one reason why in 1920 or 1921, Underhill returned formally to the Anglican Church in which she had been nominally raised (Greene 1990:74).

In the late 1920s and 1930s, Evelyn Underhill came to embrace a vocation as a teacher and retreat leader with roots in the Anglican tradition, but always with a broader practical and ecumenical appeal. In most religious spaces in the Anglican Church, she was the first woman to speak with authority and to receive public recognition. This began with her delivering the inaugural Upton Lectures at Manchester College, the Unitarian college at Oxford, in 1921—the first woman to speak in this series. Published as The Life of the Spirit and the Life of Today, Underhill’s Upton Lectures mark a transition from her writing on mysticism, which was very much rooted in her contemporaries’ interest in what American philosopher and psychologist William James (1842–1910) labeled as “religious experience” (1902). These essays shift the focus outward to the Christian spiritual life as rooted in tradition but lived out in the ordinary world. They interpret Christian faith and practice for a secular audience, drawing on insights from psychology and aesthetics, and also arguing for the importance of the institutional church as offering a framework for healthy growth and transformation in the life of faith.

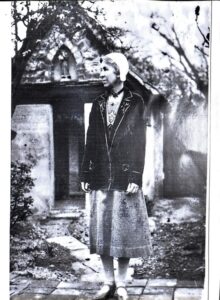

An important turning point in Underhill’s vocational development came with her first experience of retreat at Pleshey, now the diocesan retreat center for the Diocese of Chelmsford in England. [Image at right] Invited by her friend Annie Harvey, the warden at Pleshey, Underhill attended her first retreat there in 1922 and found it to be exactly what she needed. Beginning in 1924, she became a frequent conductor of retreats, both at Pleshey and elsewhere, including Canterbury Cathedral. This period saw the publication of retreat addresses as well as public lectures. Her focus in these years was no longer on mysticism as a concept; rather, she was interested in the relationship between prayer and ordinary life. Her early Pleshey retreat talks were later published by Grace Brame as The Ways of the Spirit (1993).

Underhill’s public profile grew in this period. In 1927 she was made a fellow of King’s College London. Her philosophical book, Man and the Supernatural, lays out the theological foundations of her subsequent teaching about the life of prayer, and also reflects her debt to von Hugel’s theology (Greene 1998:101–02). She also served as editor of the religious magazine The Spectator from 1929 to 1932.

In 1926, Underhill found a new spiritual director in Anglican Bishop Walter Frere (1863–1938), and during the same period she turned frequently to the Benedictine Dom John Chapman (1865–1933), of Downside Abbey, to whom she referred affectionately as “my Abbot.” She remained under Frere’s direction, while also receiving spiritual advice from Dom Chapman, for six years. The demands of an active public life as retreat conductor and spiritual writer began to take a toll as she became increasingly disabled by periodic attacks of asthma, which sometimes forced her to cancel commitments. But for the most part her pattern was to create one retreat for the year, usually offered in multiple places, and then to publish the retreat addresses as a book.

During the war years (1932–1941), Evelyn Underhill gave radio addresses and embarked upon the path of Christian ecumenism. She began spiritual direction in 1932 with Reginald Somerset Ward (1881–1962), an Anglican priest and bishop whose whole ministry was dedicated to spiritual direction and who was also a committed pacifist. During the 1930s, her retreats dug deeply into the implications of Christian theology for the active spiritual life, particularly in The School of Charity (1934) (a series of practical meditations on portions of the Nicene Creed) and The Mystery of Sacrifice (1938), which similarly engages the Eucharist. Passionate about the renewal of the life of prayer in the church, she led retreats for clergy and engaged with church leaders.

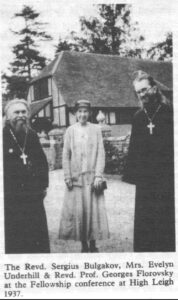

During the 1930s Underhill became increasingly interested in practices of worship across Christian denominations. [Image at right] In particular, she studied Eastern Orthodox practices and collected prayers from that tradition, using some in her retreats. Worship, published in 1936, was well ahead of its time in its detailed exploration of worship practices in Jewish, Quaker, and ecumenical Christian traditions, and it is still in use in liturgical training programs across a number of Christian denominations. Underhill’s favorite prayers, as well as her own prayer as a retreat leader, were kept in a notebook that was discovered and edited by Robyn Wrigley-Carr, as Evelyn Underhill’s Prayer Book (Wrigley-Carr 2018). In her own lifetime she also published Eucharistic Prayers from the Ancient Liturgies (1939).

A series of lectures given on the BBC Radio in 1936 was published in a slim volume entitled The Spiritual Life (1937), perhaps the most accessible and practical expression of Underhill’s mature teaching. Beginning with the practice of adoration, she shows how worship and prayer lead to communion with God, and ultimately to cooperation with God—active, committed participation in meeting the needs of a suffering world. Her words about the church speak both to her own time and to our own (Underhill 1937:88):

The Church is in the world to save the world. It is a tool of God for that purpose; not a comfortable religious club established in fine historical premises. Every one of its members is required, in one way or another, to co-operate with the Spirit in working for the greater end; and much of this work will be done in secret and invisible ways.

As the violent propaganda and division leading up to World War II began to intrude on everything, and even as she was moved out of London to escape the bombing, Underhill remained radically committed to pacifism. For her, that was the only logical outcome of the radical trust in God’s grace that Christ modeled on the cross and that Christianity preaches.

Dana Greene’s biography of Underhill gives a graphic picture of Evelyn at the end of her life, exiled to a safe place because of the war, often confined to a room devoid of the books and papers that signified her life’s work, because of acute asthma and allergies to dust, with only her crucifix on the wall (Greene 1990:142–45). Yet some who met her at that period described her as radiant, a soul truly surrendered to God (Cropper 1958:243–44). In her last years, she continued to write letters and to lead prayer groups by letter, believing in the necessity of prayer and self-abandonment. To the end of her life, even as ill health increasingly incapacitated her, she continued to write letters to longtime correspondents such as Darcie Otter, as well as better known contemporaries including Christian apologist C. S. Lewis, poet T. S. Eliot, and others. But mainly she was in touch with the members of her prayer group, urging them to pray continually for the unity of the church and for peace (Poston 2010:328–52; Cropper 1958:231–42).

Evelyn Underhill died on June 15, 1941, at Lawn House in Hampstead. She is buried in the churchyard of Hampstead Parish Church, London. In the Church of England and the Episcopal Church, June 15 is honored as her feast day in the calendar of Saints.

TEACHINGS AND PRACTICES

Evelyn Underhill’s beliefs and teachings are rarely presented in a systematic or academic way; rather, she is interested in how a Christianity grounded in prayer can transform the lives of ordinary people, even apart from belief. Accordingly, her “teachings” are best summarized by brief quotations from her various writings. It is likely for this reason that many people come to know Underhill’s work through anthologies of selections from her writings, before exploring her full retreat writings. A list of popular anthologies is included in the Supplementary Resources section below. What follows is a summary of some of her basic and recurring teachings and practices.

Underhill was convinced that mysticism is about “reality.” The book Mysticism first appeared nine years after William James’ The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), and it mirrors in many ways James’ approach and method, as well as the contemporary conversation around spirituality. In the tradition of James, Mysticism explores the religious experience of the Christian mystics, mostly in a relatively detached academic voice. In contrast to James, however, Underhill insists that what the mystics are experiencing is an encounter with something “real.” True mysticism is “active and practical,” and she explores the classic “mystic way” drawn from what she calls the “reports” of the great Christian mystics, whose knowledge is knowledge “of the heart.” “Mysticism,” she writes (Underhill 1911:81),

is not an opinion: it is not a philosophy. It has nothing in common with the pursuit of occult knowledge. On the one hand it is not merely the power of contemplating Eternity; on the other, it is not to be identified with any kind of religious queerness. It is the name of that organic process which involves the perfect consummation of the Love of God: the achievement here and now of the immortal heritage of man [sic]. Or, if you like it better—for this means exactly the same thing—it is the art of establishing his conscious relation with the Absolute.

Writing for a mixed audience of theologians, philosophers, and spiritual seekers, Underhill wants her discussion of mysticism to be embraced both by readers suspicious of institutional religion and by those who, like Underhill herself, are quietly becoming convinced that the study of Christian mysticism involves an engagement with a God who is “real” in the sense of being self-revealed through human historical and religious experience and known as a personal object of love.

When Underhill asks what makes a “true mystic,” her concern is to distinguish the tradition of the great Christian mystics from contemporary spiritual fashions of her time, especially Hermeticism and interest in the occult: what she calls, in general terms, “magic.” She addresses this first by distinguishing carefully between mysticism and magic, and then by making some connections and distinctions between the mystic and the artist. In both these areas she opens questions that continue to resonate in a world where many people describe themselves as being “spiritual without being religious.”

“Magic,” for Underhill, covers “all forms of self-seeking transcendentalism” (Underhill 1911:71). This definition reflects her context. In her own spiritual explorations, she was briefly a member of the Hermetic Society of the Golden Dawn, the core of the occult and Hermetic movements in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Britain, which drew on the older traditions of Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism. She came to the Golden Dawn through her acquaintance with Arthur Waite (1857–1942), an adept who also appreciated Catholic ritual as a way to the mystical encounter. Christopher Armstrong sees in this early association the roots of Underhill’s lifelong appreciation of ritual and spiritual discipline, and points to her nuanced 1907 article “A Defense of Magic” as a good indication of her relationship to this tradition as well as to the issues that led her to her more focused interest in Christian mysticism (Armstrong 1975:36–41; Greene 1988:31–46). Out of this period in Underhill’s life also came her short stories and novels, in the then-popular genre of what might be called “spiritual fiction” or “mystical fiction,” where the theme of the spiritual quest shapes the plot of the fictional world (Armstrong 1975:60–94; Bangley 2004:5–9). All of these explorations stress that the object of the mystical quest is not simply a psychological experience but an encounter with a Reality that is experienced and sought in Love. In the distinction between mysticism and magic, will and intention are crucial. “The fundamental difference between the two is this: magic wants to get, mysticism wants to give” (Underhill 1911:70). This brief formulation is offered as a rule of spiritual discernment (see also Staudt 2012:118–19).

Underhill taught what she often referred to as a “practical mysticism,” a spirituality grounded in everyday experience. She drew from Baron von Hugel the concept that we are inherently “amphibious” in our nature, living in two worlds. In The Spiritual Life, she writes (Underhill 1937:31–32):

[O]ur favourite distinction between the spiritual life and the practical life is false. We cannot divide them. One affects the other all the time: for we are creatures of sense and of spirit, and must live an amphibious life. . . . For a spiritual life is simply a life in which all that we do comes from the centre, where we are anchored in God: a life soaked through and through by a sense of His reality and claim, and self-given to the great movement of His will (Underhill 1937:31–32).

Failure to recognize this amphibious quality leads to our not living with “the whole of our life” (Greene 1988:69). Underhill’s retreats and letters invite people repeatedly to that “centre, where we are anchored in God.” Steadiness, practicality, and homeliness are the hallmarks of her teaching, and she is known for her use of images from everyday life. For example, she draws on her personal experience as a gardener in this passage from one of her retreats, urging against impatience in how slowly we grow in the spiritual life, and then connecting this human experience, in homely terms, to the Incarnation itself (Underhill 1934:48):

All gardeners know the importance of good root development before we force the leaves and flowers. So our life in God should be deeply rooted and grounded before we presume to expect to produce flowers and fruits; otherwise we risk shooting up into one of those lanky plants which can never do without a stick. We are constantly beset by the notion that we ought to perceive ourselves springing up quickly, like the seed on stony ground; show striking signs of spiritual growth. But perhaps we are only required to go on quietly, making root, growing nice and bushy; docile to the great slow rhythm of life.

Here and elsewhere, Underhill pushes back against her spiritual directees’ impatience to grow in the spiritual life, and especially their desire for comforting or dramatic mystical experiences, Rather, she suggests, most of us are given something more like a steady and deepening invitation to growth. The organic metaphor she uses here typifies the wisdom about the spiritual life that she draws from her own experience and shares with others.

The life of the spirit, for Underhill, is lived out in ordinary activities and relationships. It is not about following doctrines or even solely about church attendance, though the impulse to worship is, for her, a core characteristic of all human spirituality. In an early essay, she asserts: “The spiritual consciousness is more often caught than taught. We most easily recognize spiritual reality when it is perceived transfiguring human character, and most easily attain it by sympathetic contagion” (Greene 1988:81).

The accounts of Underhill’s presence and personality by those who knew her testify to the ways that she herself was a source of this spiritual “contagion” (Cropper 1958:245–49). Her own devotion to the practice of prayer in all of life is evident when she reminds an assembly of Sunday school teachers (Underhill 1946:186):

God is always coming to you in the sacrament of present moment. Meet and receive him then with joy in that sacrament, however unexpected its outward form may be. You can and should receive Him, in every sight and sound, joy, pain, opportunity and sacrifice; and receive Him, not merely for your own benefit and happiness, but so that you can freely give (Underhill 1946:186).

She takes the phrase “sacrament of the present moment” from the seventeenth-century spiritual writer Jean-Pierre de Caussade (1675–1751), but makes it her own, underscoring her commitment to a spiritual life lived out in all circumstances of life. The idea that even unexpected and unwelcome events can be the “matter” of a sacrament invites a practice of mindfulness and gratitude in all aspects of ordinary experience.

Underhill’s emphasis throughout retreats and letters of direction is on an explicitly Christian spiritual practice and prayer leading to action in the world. She connects these practices to the orthodox teachings of Christianity in a number of her retreats and addresses. In her 1921 Upton lecture, “Institutional Religion and the Life of the Spirit” (Underhill 1921:115–43), she points to two necessary callings in the life of the church: the priest, who tends the sacraments and holds the traditions, and the prophet, who calls the church back to a more faithful and vivid relationship with the God we worship. Here and in Man and the Supernatural and The Mystics of the Church she points out that all great reforms in the life of the institutional church have come about, not from outside, but from those who sought radical change within.

Perhaps most compellingly, The School of Charity, Light of Christ, and The Mystery of Sacrifice interpret through homely example and storytelling the events of the Gospels and especially the importance of the Incarnation and the Crucifixion as ways of understanding a spiritual life lived out in this world. In her Pleshey retreat addresses published as Light of Christ, she draws together mysteries in the life of Jesus with recognizable human experiences of suffering, loss, and betrayal (Underhill 1932).

Underhill is particularly firm in her work with clergy, insisting that for them the life of prayer needs to be primary, as it often is not amid the demands of institutional life. In Concerning the Inner Life, a retreat given to Anglican clergy in 1926, she exhorts (Underhill 1926:94):

We are drifting toward a religion which consciously or unconsciously keeps its eye on humanity rather than on Deity, which lays all the stress on service, and hardly any of the stress on awe and that is the type of religion, which in practice does not wear well. . . . It does not lead to sanctity: and sanctity after all is the religious goal.

In a letter to Archbishop Cosimo Lang in 1930, she writes even more urgently(Underhill 1930) :

God is the interesting thing about religion, and people are hungry for God. But only a priest whose life is soaked in prayer, sacrifice and love can, by his own spirit of adoring worship, help us to apprehend Him.

Here we see another hallmark of Underhill’s work in the church: her boldness in speaking truth to authority in the institutional church, and especially in exhorting clergy leaders to embrace for themselves the practices that they are ordained to teach and model.

For Underhill, spiritual life begins with an awestruck, delighted focus on God alone, for God’s own sake. That experience of adoration makes possible a communion with the Creator that also exposes and draws on our own creativity, as human beings made in the image of our Creator. Underhill gives us a rich and original God-image in naming the Holy One as “Creative Love” and as the “Artist-Lover” (Underhill 1934:15).

To stand alongside the generous Creative Love, maker of all things visible and invisible (including those we do not like) and see them with the eyes of the Artist-Lover is the secret of sanctity. St. Francis did this with a singular perfection; but we know the price that he paid. So too that rapt and patient lover of all life, Charles Darwin, with his great, self-forgetful interest in the humblest and tiniest forms of life—not because they were useful to him, but for their own sakes—fulfilled one part of our Christian duty far better than many Christians do. It is a part of the life of prayer, which is our small attempt to live the life of Charity, to consider the whole creation with a deep and selfless reverence; enter into its wonder, and find in it the mysterious intimations of the Father of Life, maker of all things, Creative Love.

Always a devotee of St. Francis (d. 1226), here she also recognizes the devotion of the scientist Charles Darwin (1809–1882). Both men are, for her, guides to the practice of adoration, “standing beside” that Creative Love and sharing in the Creator’s joy in Creation. In doing this she affirms creativity as a basic human impulse, both in prayer and in intellectual curiosity, always reflecting and participating in the divine life.

The mystical life was active in worship, intercession, and the power of prayer, according to Underhill. Her later writings, notably The Spiritual Life, Abba, and Worship, insist that the life of prayer begins and ends in adoration, the awestruck, delighted recognition of the divine reality and presence, a basic human impulse which is ultimately lived out in a life of communion and cooperation with God’s purposes in the world. This is what she means when she points out that the impulse to worship is closely tied to the impulse toward self-consecration and sacrifice.

At a time when worship in the Anglican Church tended to be routine and bland, Underhill calls people back to the reasons why we worship, insisting again that the ultimate goal of communion with God begins in adoration. In an age of skepticism and even boredom with the idea of worship, she insistently focuses on “God alone.” Indeed, her memorial plaque in the chapel at Pleshey includes a quotation from the English poet John Donne (1571/1572–1631): “Blessed be God that He is God, only and divinely like Himself” (Williams 1943:45).

Finally, Underhill’s writings on peace reveal her strong commitment to pacifism. [Image at right] As the Second World War began, Underhill found herself among the small minority of pacifists in Britain, believing that the call to the Way of the Cross required the renunciation of violence and a radical trust in God’s ultimate will. “The true pacifist is a redeemer,” she writes, “and must accept with joy the redeemer’s lot. He too is self-ordered, without conditions, for the peace of the world” (Greene 1988:201–02). During this period, she was living outside of London, and suffering from severe asthma. Nonetheless, she sustained her correspondence with a prayer group who called themselves her “spiritual kindergarten,” leading them in prayers for peace. Her writings from this period reflect this radical commitment to the peace that Christians are called to embrace and sustain, even at cost to themselves (Greene 1988:200).

Christians are bound to the belief that all creation is dear to the Creator, and is the object of His cherishing care. The violent as well as the peaceful, the dictators as well as their victims, the Blimps as well as the pacifists, the Government as well as the Opposition, the sinners as well as the saints. All are children of the Eternal Perfect. Some inhabitants of this crowded nursery are naughty, some stupid, some wayward, some are beginning to get good. God loves, not merely tolerates, these wayward, violent, half-grown spirits, and seeks without ceasing to draw them into His love. We, then, are called to renounce hostile attitudes and hostile thoughts towards even our most disconcerting fellow sinners; to feel as great a pity for those who go wrong as for their victims, to show an equal generosity to the just and unjust. This is the only peace-propaganda which has creative quality, and is therefore sure of ultimate success. All else is scratching on the surface, more likely to irritate than to heal.

This insistence on Christ’s command to “love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” (Matthew 5:43-44) was as radical in its own time as it is in our own. Though Underhill did not live to see the full revelation of the Third Reich’s atrocities, she was insistent in her lifetime that we cannot defeat violence with violence. In this, her teaching resonates with Christian pacifists throughout time; one thinks of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929–1968) in the next generation, insisting “Violence cannot cast out violence: only love can do that” (King 1967:67).

LEADERSHIP

Evelyn Underhill’s leadership in the church took the form of what Anglican spiritual writer Charles Williams has called the “motherhood of souls,” lived out in her work as a spiritual director and as retreat leader (Williams 1943:26; Wrigley-Carr 2020:85–137). Her letters of direction were tailored to individual recipients, and often display playfulness and strong affection even as she offered challenging advice. Those who knew her described her as radiating love and serenity, and experienced her as a “channel” of God’s love (Wrigley-Carr 2020:88–90). Though each person’s needs were different, Underhill consistently urged people away from self-focus and toward surrender to God’s guidance and desire, especially urging them away from excessive focus on their own sins and failings. She practiced and recommended setting aside a definite time for daily prayer, as well as spontaneous responses to the presence of God during the day. When people encountered times of dryness, she encouraged them to carry on quietly, trusting in God’s faithfulness.

As a retreat leader, she was firm about the importance of setting time apart. In her frequently reprinted essay on “The Need for Retreat,” [Image at right] she recalls Christ’s exhortation to “go into your room and shut the door” for times of prayer (Matthew 6:6):

“Shut the door,” I think we can almost see the smile with which He said those three words: and those three words define what we have to try to do. Anyone can retire into a quiet place and have a thoroughly unquiet time in it—but that is not making a Retreat! It is the shutting of the door which makes the whole difference between a true Retreat and a worried religious weekend (Roberts 1981:5).

Consistent with her teaching about adoration as the ground of prayer, Underhill also reminds retreatants that their motto should be “God Only, God in Himself, sought for Himself alone”:

The object of Retreat is not Intercession or self exploration, but such communion with Him as shall afterwards make you more powerful in intercession; and such self-loss in Him as shall heal your wounds by new contact with His life and love (Roberts 1981:5–6).

In our own time, where distraction and busy-ness perennially challenge those who seek to deepen the life of prayer, Underhill’s words about retreat continue to ring true for those seeking the mystical life.

Late in her life she exercised her “Motherhood of Souls” through her correspondence with groups who were dedicated to prayer. From her experience in the Entente as well as her growing concern with prayers for peace, Underhill became a quiet leader of prayer groups engaged in intercessory prayer. Though she claimed not to be good at praying for specific outcomes, she saw prayer as a powerful and transformative force. In a talk given to her prayer group, she writes (Underhill 1941:55):

A real man or woman of prayer, then, should be a live wire, a link between God’s grace and the world that needs it. In so far as you have given your lives to God, you have offered yourselves, without conditions, as transmitters of His saving and enabling love. . . . One human spirit can, by its prayer and love, touch and change another human spirit; it can take a soul and lift it into the atmosphere of God. This happens, and the fact that it happens is one of the most wonderful things in the Christian life.

Praying for peace, especially as the war intensified, became a primary activity in Underhill’s last years. She viewed the practice of prayer as at one with the total trust in the Divine purpose that she named as “abandonment” to God (Greene 1990:140–42). This prayer-practice grounded her commitment to pacifism and the leadership in prayer that was the focus of her final years.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Underhill was very much a woman of her time and class, and her achievement as a public figure in the Anglican Church and an enduring guide to the mystical life is all the more remarkable for that. [Image at right] She would not qualify as a “feminist” in any twenty-first-century sense. For example, she did not support women’s suffrage or women’s ordination, and she offered no explicit condemnation of patriarchy. Indeed, some contemporary readers may be put off by her conventional use of masculine language for God and for “man.” More problematically, her personal journals reveal a fierce scrupulosity about her own inner life, and a tendency to self-condemnation, which goes against the grain of the kind of healthy self-affirmation that most contemporary feminist theologies encourage among women. In her journals she condemns herself for her “tendency to tyranny, exactingness, getting my full rights” and expresses belief that her “craving for human affection must be crushed; must give love freely and not examine the quality of what I get” (Greene 1992:84–85). Her directors (all men) urged her toward more fully accepting herself as a beloved child of God, but without examining what might be the root causes of the resentments of which she accused herself (Greene 1992:84–92).

Meanwhile her own letters to directees urged them to let go of excessive focus on their faults; in this she wrote from her own experience. Historian and biographer Dana Greene comments on the “ferocity” of Underhill’s self-condemnation and the depth of her despair at times. On the other hand, feminist readers of Underhill may recognize some of the actual struggles of women to understand themselves as whole and beloved in a patriarchal world.

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGIONS

Underhill signed her letters “ESM,” using her married name Evelyn Stuart Moore, though she published under the name Evelyn Underhill. Until recently, her gravestone in the churchyard of Hampstead Parish Church read only “Hubert Stuart Moore and his wife Evelyn.” But in 2021, on the eightieth anniversary of Underhill’s death, Hampstead Parish Church commissioned a covering stone with her name inscribed as “Evelyn Underhill.”

In his foreword to Christopher Armstrong’s biography, Archbishop Michael Ramsay said of Underhill that “in the twenties and thirties there were few, if indeed, any, in the Church of England who did more to help people to grasp the priority of prayer in the Christian life and the place of the contemplative element within it” (Armstrong 1975:x).

From her early scholarship on mysticism, through her classic retreat work and direction and her richly ecumenical later work on worship, Evelyn Underhill managed to articulate afresh the gifts of a Christian spiritual path, pursued within a long tradition of mystical wisdom. [Image at right] A woman of relative privilege, Underhill witnessed the social and emotional upheavals that followed the First World War and continued through the Second World War. She remains a resonant voice for all who suspect that genuine transformation in the world can come about only through the core spiritual life of openness to the holy and loving compassion for all people. Her writings and retreats emphasize the “homeliness” or humble ordinariness of most people’s lives, and our “amphibious” identity as people of both matter and spirit, called to live with the whole of our lives. A reflection in The School of Charity provides a good summary of the way she lived out her own vocation: “The final test of holiness is not seeming very different from other people, but being used to make other people very different; becoming the parent of new life” (Underhill 1934:32). Generations of readers have continued to find in Underhill’s letters, retreats, and writings an engaging spiritual parent, bringing forth in them new life. It is likely that future generations will as well.

IMAGES

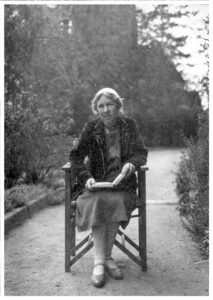

Image # 1: Evelyn Underhill, January 1, 1926. Wearing Jewelry, a gift from her husband. Pleshey Retreat House. Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ Category:Evelyn_Underhill#/media/File:Evelyn_Underhill_1926.png.

Image # 2: Evelyn Underhill as a girl. Photo by William Edward Downey (1855–1908) Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Catego

Image # 3: Evelyn Underhill standing, at Pleshey Retreat House (between 1925 and 1930). Courtesy of King’s College London: College Archives, K/PP75/7/1.

Image # 4: Evelyn Underhill at Pleshey Retreat House in the 1930s flanked by Orthodox priests. Courtesy of King’s College London: College Archives, K/PP75/7/49.

Image # 5: Evelyn Underhill as a young woman on the cover of Treasures from the Spiritual Classics edition of her works. Public Domain.

Image # 6: Evelyn Underhill sitting in conductor’s room at Pleshey Retreat House. Courtesy of King’s College London: College Archives, K/PP75/7/1.

Image # 7: Evelyn Underhill seated, with her prayer book, at Pleshey Retreat House. Courtesy of the Chelmsford Diocesan House of Retreat, Pleshey.

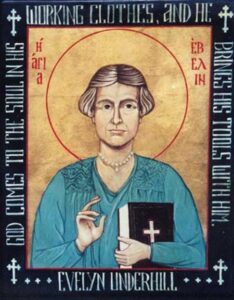

Image #8: Icon of Evelyn Underhill created by Suzanne Schleck. Courtesy of the Evelyn Underhill Association.

REFERENCES

Allchin, A. M. 2003. Friendship in God: The Encounter of Evelyn Underhill and Sorella Maria of Campello. Oxford, UK: SLG Press.

Armstrong, Christopher. 1975. Evelyn Underhill (1875-1941): An Introduction to her Life and Writings. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdman’s.

Brame, Grace, ed. 1990. Evelyn Underhill: The Ways of the Spirit. New York: Crossroad.

Bangley, Bernard, ed. 2004. Radiance: A Spiritual Memoir by Evelyn Underhill. Orleans, MA: Paraclete Press.

Cropper, Margaret. 2003 [1958]. The Life of Evelyn Underhill: An Intimate Portrait of the Groundbreaking Author of Mysticism. Nashville, TN: SkyLight Paths.

Greene, Dana, ed. 1993. Evelyn Underhill: Fragments From an Inner Life. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock.

Greene, Dana. 1990. Evelyn Underhill: Artist of the Infinite Life. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Greene, Dana, ed. 1988. Evelyn Underhill: Modern Guide to the Ancient Quest for the Holy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

James, William. 2004 [1907]. The Varieties of Religious Experience. New York: Barnes and Noble.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. 1967. Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? New York: Harper and Row.

Oberg, Delroy. 1992. Evelyn Underhill: Daily Readings with a Modern Mystic. Mystic, CT: Twenty-Third Publications. Originally published by Darton Longman & Todd Ltd, London, and titled Given to God: Daily Readings with Evelyn Underhill.

Poston, Carol, ed. 2010 The Making of a Mystic: New and Selected Letters of Evelyn Underhill. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press

Roberts, Roger L., ed. 1982. The Fruits of the Spirit, by Evelyn Underhill. Wilton, CT: Morehouse-Barlow, Inc.

Staudt, Kathleen Henderson. 2012. “Rereading Evelyn Underhill’s Mysticism.” Spiritus 12:113–28.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1947 [1926]. “Concerning the Inner Life.” Pp. 89-115 in The House of the Soul and Concerning the Inner Life. London: Methuen.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1946. Life as Prayer and Other Writings of Evelyn Underhill. Edited by Lucy Menzies. Harrisburg PA: Morehouse Publishing. Originally published as Collected Papers of Evelyn Underhill. London: Longmans, Greene.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1940. Abba: Meditations on the Lord’s Prayer. London: Longmans, Green.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1938. The Mystery of Sacrifice: A Meditation on the Liturgy. London: Longman’s, Green.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1937. The Spiritual Life. London. Hodder & Stoughton.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1934. The School of Charity: Meditations on the Christian Creed. London: Longman’s, Green.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1932. Light of Christ: Addresses Given at the Retreat House of Pleshey. London: Longman’s, Green.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1930. A Letter from Evelyn Underhill to Archbishop Cosmo Lang (found among her papers). Acessed from www.anglicanlibrary.org/underhill UnderhillLettertoArchbishopLangofCanterbury.pdf on 25 August 2024.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1927. Man and the Supernatural. London: Methuen.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1921 The Life of the Spirit and the Life of Today. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1915. Immanence: Poems. London: J. M. Dent.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1915. Practical Mysticism. London: E. P. Dutton.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1911. Mysticism: A Study in the Nature and Development of Man’s Spiritual Consciousness London: Methuen.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1995 [1936]. Worship. New York: Crossroads.

Williams, Charles, ed. 1943. Letters of Evelyn Underhill. London: Longman’s, Green.

Wrigley-Carr, Robyn. 2020. The Spiritual Formation of Evelyn Underhill. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK).

Wrigley-Carr, Robyn, ed. 2018. Evelyn Underhill’s Prayer Book. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK).

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Oberg, Delroy. 2015. Evelyn Underhill and the Making of ‘Mysticism’: Celebrating Underhill, Evelyn. 1925. The Mystics of the Church. London: James Clarke. The Centenary of the 1st Edition March 2, 1911. Self-published.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1960 [1942]. The Fruits of the Spirit. London: Longman’s, Green.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1919. Jacopone Da Todi: Poet and Mystic 1228–1306, A Spiritual Biography. With a Selection from the Spiritual Songs. The Italian Text Translated into English Verse by Theodore Beck. London: J. M. Dent.

Anthologies of Evelyn Underhill’s Writings

Barkway, Lumsden, and Lucy Menzies, eds. 1953. An Anthology of the Love of God, from the Writings of Evelyn Underhill. London: A. R. Mowbray.

Belshaw, G. P. Mellick., ed. 1964. Lent with Evelyn Underhill. Oxford, UK: A. R. Mowbray.

Blanch, Brenda, and Stuart Branch, eds. 1992. Heaven a Dance: An Evelyn Underhill Anthology. London: London: Triangle, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, Holy Trinity Church.

Griffin, Emilie, ed. 2003. Evelyn Underhill: Essential Writings. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Press.

Oberg, Delroy. 1992. Evelyn Underhill: Daily Readings with a Modern Mystic. Mystic, CT: Twenty-Third Publications. Originally published by Darton Longman & Todd Ltd, London, and titled Given to God: Daily Readings with Evelyn Underhill.

Webber, Christopher L. 2006. Advent with Evelyn Underhill. Harrisburg, PA: Morehouse Publishing.

Wrigley-Carr, Robyn, ed. 2021. Music of Eternity: Meditations for Advent with Evelyn Underhill. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK).

LINKS

Hermetic Society of the Golden Dawn

Diocesan Retreat House at Pleshey, Diocese of Chelmsford

Evelyn Underhill. Anglican Library. www.anglicanlibrary.org/underhill

“My Favorite Mystic: Evelyn Underhill. Podcast interview with Jane Shaw

A Memorial for Evelyn Underhill (Hampstead Parish Church)

Publication Date:

26 August 2024