CHRISTINE DE PIZAN TIMELINE**

** (Throughout the Timeline, publication date refers to the first manuscript since Christine’s works predate the printing press.)

1364/1365: Christine de Pizan was born in Venice.

1368: Thomas de Pizan moved his family members, including daughter Christine, from Venice to Paris, where they were then presented to King Charles V, the Wise.

1380 (early): Christine, aged fifteen, married Étienne de Castel, royal notary/secretary.

1380: Charles V the Wise, Thomas’ patron, died; this was unfortunate for both France and Christine. His brothers would vie for control, then his well-intentioned son and successor, Charles VI, would later go mad.

1383: Christine’s elder son, Jean, who would become a notary at Henry IV of England’s court, then at the French court, was born.

1389: Christine’s father, who left a meager and financially tangled legacy, died.

1390 (late): Christine’s husband died from plague. Christine was now a widow with three children, her mother, and a niece to provide for.

1394–1402: Christine began her prolific literary career.

1397: Marie de Castel, Christine’s daughter, entered the Royal Dominican Priory at Poissy, where Christine would join her during her final years.

1398 (December): Christine met John Montagu, third earl of Salisbury, in Paris, winning his favor with her first lyric poems. Her son Jean de Castel traveled to England, and joined the household of Salisbury, then, after 1400, the court of King Henry IV of England.

1399: Christine’s successful debut at English noble court launched her as a serious author in France.

1399 (May 1): Epistre au dieu d’Amours (The God of Love’s Epistle), Christine’s first defense of women, was published.

1399–1402: Enseignemens moraux (Moral Teachings), a common-sense moral manual in verse for her teenaged son, Jean de Castel, was published.

1400 (January 7): Earl of Salisbury, Christine’s first patron, was executed for participation in a failed plot to assassinate King Henry IV.

1400 (April): Livre du Dit de Poissy (Book of the Tale of Poissy), poem set at Poissy Abbey, relating a debate on love, was published.

1400: Livre du Debat de Deux amans (Book of the Debate of Two Lovers), a prose and verse narrative about a courtly, illicit love affair from the woman’s point of view, was published. Livre des Trois Jugemens (Book of the Three Judgments), another love debate poem, also was published.

1400–1401: Epistre que Othea la deesse envoya a Hector de Troye (Epistle that the Goddess Othea sent to Hector of Troy), a manual for a prince, and Christine’s first primarily prose work consisting of 100 morally-glossed story-moments from history with illustrative miniatures, was published.

1400–1401: Verse epistles and love-debate poems, such as Le Dit de Poissy (Tale of Poissy), Debat de Deux amans (Debate of Two Lovers), Livre des Trois Jugemens (Book of Three Judgments), were published.

1401–1404: Christine de Pizan entered, joining prominent male intellectuals, France’s first literary and feminist debate: Epistres du Debat sus le Rommant de la Rose entre notables personnes (Epistles of the Debate on the Romance of the Rose among notable personages).

1402 (February 14): Dit de la Rose (Tale of the Rose), dream-vision poem with female guide figure, a polemic against the misogyny and immorality in the widely admired Roman de la Rose (Romance of the Rose), was published.

1402 (October 5)–1403 (March 20): Livre du Chemin de lonc estude (Book of the Path of Long Study), the first evidence of Dante’s influence in French literature, was published.

1402–1403: Christine’s first religious poems were published.

1403: Livre du Dit de la Pastoure (The Shepherdess’ Tale), a notably feminist take on the familiar male-centered theme of a shepherdess seduced and abandoned by a knight, was published.

1403: Livre de la Mutacion de Fortune (Book of Fortune’s Mutability), her lengthiest work, a universal moralized history in verse was published.

1403–1405: Livre du Duc des vrais amans (Book of the Duke of True Lovers), emphasizing the lady’s suffering in a traditionally male-centered courtly love affair, was published.

1403–1406: Livre de Prodommie de l’omme (Book of Human Integrity), written for Louis, Duke of Orléans, urging him to be prudent in dealing with his ruthless rivals, was published.

1404 (November 30): Livre des Fais et bonnes meurs du sage roy Charles V (Book of the Deeds and Good Practices of the Wise King Charles V), the first royal biography written by a woman, was published.

1404–1405: Livre de la Cité des dames (Book of the City of Ladies), the first feminist-revisionist history of ancient to contemporary secular and religious women, Christine’s best-known work for modern times, was published.

1404: Une Epistre a Eustace Morel (An Epistle to Eustace Morel) (Eustache Deschamps), rhymed moral–political sharing of ideas, to which Deschamps responded warmly in a ballade tribute, was published.

1404–1410: Ballades de divers propos (Ballades for Different Occasions) continued.

1405–1410(?): More ballades, titled Autres balades (Other Ballades), were published.

1405: Epistre a la Reine (Epistle to the Queen), which exhorted Queen Isabeau of France directly to intervene in preventing violent civil unrest caused by feuding political factions, was published.

1405: Proverbes moraux (Moral Proverbs), a more aphoristic version of residual material from the Moral Teachings, was published.

1405: Livre de l’Advision Cristine (Book of Christine’s Vision), arguably the first serious autobiographical narrative in French, was published.

1405–1406: Le Livre des trois vertus (Book of the Three Virtues), converting City of Ladies into a practical manual for women of all social ranks, was published. The work was sometimes called Tresor de la Cité des Dames (the title given by its first printer, Antoine Verard in 1497), but modern scholars have retained the original, Three Virtues.

1407: Livre du Corps de policie (Book of the Body Politic) was published. Ironically, Duke Louis of Orléans was then assassinated by cousin Duke John of Burgundy, both of whom were Christine’s patrons, causing more political upheaval.

1408–1410: Livre de Prudence (Book of Prudence), a reworking of Prodommie (Human Integrity), as a guide to help Queen Isabeau, was published.

1407–1410: Publication of Encore Autres Balades (Still More Ballades), then Cent Ballades d’Amant et de Dame (One Hundred Ballades of Lover and Lady), Christine’s last ballad sequence, focused on the love dynamic of just one couple.

1409: Publication of Livre des Sept psaumes allegorisés (Book of Seven Allegorized Psalms), meditation on the Penitential Psalms.

1410: Publication of Lamentacion sur les maux de France (Lamentation on France’s Ills), powerfully poignant prose appeal to queen, royal council, and dukes to intervene and quell the destructive effects of the civil war between Burgundians and Armagnacs/Orléanists.

1410: Publication of Livre des Fais d’armes et de Chevallerie (Book of Feats of Arms and Chivalry), first military treatise and male courtesy manual written by a woman.

1412–1414: Publication of Livre de Paix (Book of Peace), for Louis of Guyenne, first dauphin. Unfinished due to Christine’s despair over constant war.

1414 (New Years Day?): Christine presented Queen Isabeau of France with major illuminated manuscript of her works thus far, now the London British Library Harley 4431, or “Queen’s Manuscript.”

1416–1418: Publication of Epistre de Prison de Vie Humaine (Epistle on the Prison of Human Life), to console the widows of the many knights killed in battle with English at Agincourt.

1418: Burgundians slaughtered Armagnacs in Paris. Christine fled Paris and entered self-imposed exile at the Royal Dominican abbey of St. Louis at Poissy.

1420–1428: Publication of Heures de Contemplacion sur la Passion de Nostre Seigneur (Hours of Contemplation on Our Lord’s Passion).

1425: Death of Christine’s elder son, Jean de Castel, a notary, aged 42; her grief possibly inspiring her Hours of Contemplation.

1429 (July 17): Publication of Ditié de Jehanne d’Arc (Song of Joan of Arc), a patriotic poem celebrating Joan’s exploits. Christine’s final known work, and the first literary work on Joan of Arc by a non-anonymous French author.

1430/1431[?]: Death of Christine de Pizan, probably at Poissy Abbey.

1440–1442: Martin Le Franc in Le Champion des Dames (The Ladies’ Champion) praises both Christine de Pizan and Joan of Arc, helping to inaugurate a long, heroically positive tradition for each.

HISTORY/BIOGRAPHY

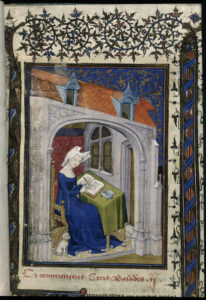

Christine de Pizan is considered the first true feminist author in Western Literature. [Image at right] While not the first accomplished woman author by any means, she was the first to cultivate a feminist ideology nurtured by combining classical-humanistic learning and Christian spirituality, which she incorporated into her poetics, themes, and political activism. Key events in her life, often caused by the Black Death and the Hundred Years War (1337–1453) between France and England, shaped her exceptional career, as she herself expressed in her work, notably Fortune’s Mutability and Christine’s Vision, together with her strongly self-deterministic personality.

Christine de Pizan is considered the first true feminist author in Western Literature. [Image at right] While not the first accomplished woman author by any means, she was the first to cultivate a feminist ideology nurtured by combining classical-humanistic learning and Christian spirituality, which she incorporated into her poetics, themes, and political activism. Key events in her life, often caused by the Black Death and the Hundred Years War (1337–1453) between France and England, shaped her exceptional career, as she herself expressed in her work, notably Fortune’s Mutability and Christine’s Vision, together with her strongly self-deterministic personality.

She was born in Venice in 1364/1365. Her father was Tommaso da Pizzano, a Bolognese professor, doctor, and highly regarded astrologer. Invited to the court of King Charles V of France (1338–1380) at the Louvre palace, he moved his family to Paris and became known as Thomas de Pizan. Christine’s two brothers, Paolo and Aghinolfo, appear to have been unexceptional. By contrast, Thomas recognized his daughter’s intelligence and zeal for learning early on, providing her with what would then, and even now, be considered an “utterly virile education” in Latin and the sciences (Molinier 1904:62). Christine’s mother, also the daughter of an eminent astrologer, Tommaso Mondino da Forlì, seems more traditional in her expectations of her studious daughter. Probably for this reason, Christine represents herself as primarily her learned father’s daughter with little mention of her mother as a real person.

At age fifteen Christine married a young Picard nobleman, Étienne du Castel, a royal notary, to whom she bore two sons, Jean and Étienne (the latter, about whom no more is known, possibly died young) and a daughter, Marie. While parentally arranged and thus socially advantageous, their marriage was also exceptionally loving for ten happy years, as attested, for example, in her Other Ballades, 26, titled “A Sweet Thing Is Marriage” (Christine de Pizan 2012).

Her fortunes then shifted for the worse. First her father died, leaving the couple little, due to diminished professional success and poor money management. This was followed by Étienne’s sudden death of plague a year later in 1390 while on a diplomatic mission. Étienne’s financial legacy was also minimal, and legally problematic. At age twenty-five, therefore, Christine was an impoverished widow with three children, her mother, and a niece to support.

Taking advantage of her paternal education and availing herself of Étienne’s connections, she first worked as a copyist in legal-notarial offices. Further legal experience was less happily afforded her when she had to fight her father’s and husband’s creditors for years to recoup her meager inheritance (Fortune, vv. 379–468; Vision, pt. 3, chs. 5–6).

Soon thereafter, in about 1394, she began her literary career, first as a lyric poet seeking solace for her grief and solitude, followed by poems on the joys of love. Her concern for improving the status of women, reforming the morality of life at court and in overall society is detectable even in these early lyrics comprising One Hundred Ballades. (In this instance, a ballade is a set poetic genre inspired by early dance forms, not a modern ballad). Additional lyric-poetic sequences followed. Christine was a woman writing love poetry from a woman’s point of view, and not simply mimicking male courtly-poetic style. These early efforts attracted patrons, such as John Montaigu or Montacute (ca. 1350–1400), third Earl of Salisbury.

Her poems, in which she presents herself as a “lonely little woman”—seulette (e. g., One Hundred Ballades, 11)—displayed enough skill to charm her male readers into forgetting that their author was a mere woman. Yet they often presented a fresh viewpoint, such as a woman’s perspective on fin amors, “courtly love,” that is, extramarital liaisons refined and validated by the vocabulary of love as found in Christian caritas and Mariolatry; or the prevailing courtly (=high society) taboo code created by and favoring men, while women inevitably suffered social disdain. Christine’s brand of courtly love expressed in her poetry differs by exhibiting purer, more genuine sentiments rather than thinly disguised lust. Her courtly love also advocated marriage instead of eschewing it.

Enlarging her scope of moral reform, Christine soon started composing didactic works of verse and prose to address the socio-political tumult pervading her adoptive country during the Hundred Years War and related civil wars. She believed in France’s potential as a model Christian kingdom, over those of England, Italy, and others, and urged French nobles to pursue this mission.

During this phase of her career (1402–1403), she also tried her hand at devotional poetry, as evidenced in three prayers in verse stanzas: A Prayer on Our Lady; The Fifteen Joys of Our Lady; and Prayer on Our Lord’s Life and Passion. A distinctive feature of these is her insertion of the Latin incipit from an “Ave Maria” or “Pater Noster” from the official liturgy as a refrain to each of her French stanzas. All exemplify the prevailing “affective piety” (in which the audience, focusing on Christ’s Passion, revisits his suffering on the cross, so that experiencing such profound emotion leads to spiritual perfection) a characteristic of lay society in her time. Scholars have observed the strong influence of the writings of Jean Gerson (1363–1429), chancellor of the University of Paris, upon her work (Boulton 2003:215–16). Christine probably hoped that the queen and other powerful nobles would heed her writings’ message of virtue and peace.

France was not only long engaged in war with a foreign power, England, but also inwardly rent by civil war among rival dukes. Such disarray prevailed because the young, progressive-minded king of France, Charles VI (1368–1422), was going mad, leaving his wife Queen Isabeau of Bavaria (ca. 1370–1435) to turn to consorts for protection and guidance. His uncles, competing for power and wealth, thus ruled in Charles’ stead with varying success. Most of these dukes were also patrons of Christine at one time or another. Not content merely to survive the complex patronage system in this volatile society, Christine sought to educate these redoubtable nobles morally and spiritually. She attracted the queen’s support and that of other noble female patrons, such as Valentina Visconti (1371–1408), wife of patron Louis I, Duke of Orléans, and Charles Vi’s brother.

Christine also practiced what she preached by hiring artistic women as copyists (scribes) and illuminators (illustrators and decorators) for her manuscripts whenever possible. Here, she was not simply being charitable but also practical, for such a labor force proved indispensable toward establishing her own atelier (manuscript-producing workshop) in Paris to “publish” her works in this pre-Gutenberg press era, to accommodate as many patrons as possible.

For her erudite works, aimed at her highly educated humanistic colleagues and patrons, she deployed an enormous array of scientific, theological, and historical sources, thanks to her unusual education from her father. Moreover, through him and her late husband, she gained access to Charles V’s exceptional library, one of the finest in the Western world. It became the future Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, attracting a multitude of scholars to this day and housing many manuscripts of her works.

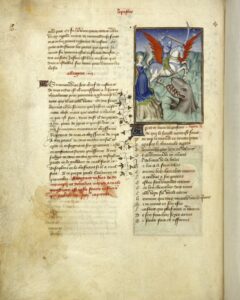

Christine began to write works of moral instruction for princes, using an innovative text–image format, as in her primarily prose Epistle of Othea to Hector (1400–1401). Othea, like her Greek name, is a conglomerate ancient goddess of lay and sacred wisdom, while Hector, the future noble prince of Troy, is Othea’s pupil, another conglomerate—a future prince plus her own son, Jean de Castel, for whom Christine envisioned a successful career at court. The “mirror for princes” was already a popular didactic genre, but Christine rendered it most appealingly as a multimedia didactic experiment (Ignatius 1979). This epistle contains one hundred episodes from myth and history, here converted into “teaching moments” for a good Christian prince. Her method consisted in borrowing the first three of the so-called four methods of scriptural interpretation (literal, allegorical, moral, anagogical) from Christian exegesis. She retold the tale at each increasingly elevated spiritual level—the literal “text” in rhyme, followed by the two interpretive levels in prose (“gloss” and “allegory”). She then illustrated them with exquisite miniatures produced in  her atelier. Furthermore, she told the reader just how she wished her text to be read in all of these aspects (Tuve 1966:33–40; 285–301; Hindman 1986). She thereby entertained, then edified, her royal readers. If her heroes and heroines were often taken from pagan Greek and Roman myths, their stories and the moral lessons derived therefrom are always to be read in Christian terms. [Image at right]

her atelier. Furthermore, she told the reader just how she wished her text to be read in all of these aspects (Tuve 1966:33–40; 285–301; Hindman 1986). She thereby entertained, then edified, her royal readers. If her heroes and heroines were often taken from pagan Greek and Roman myths, their stories and the moral lessons derived therefrom are always to be read in Christian terms. [Image at right]

Christine penned The Book of Fortune’s Mutability (1403), for Duke Philip the Bold of Burgundy (1342–1404), also presenting a copy to John, Duke of Berry (1340–1416), since Philip died so soon thereafter. This work contains 24,000 verses divided into seven parts, as if foreshadowing Shakespeare’s poem, “The Seven Ages of Man” (As You Like It, II, 7) already existed before Christine’s time (https://muse.jhu.edu/article/494378/summary). She incorporates an allegorized version of her early life story, fraught with tribulation, into the larger framework of universal moralized history, such as it was then known—from ancient times to her own—to understand and cope with Fortune’s often cruel caprice.

Duke Philip II the Bold of Burgundy (1342–1404) was so impressed by Christine’s Fortune that he commissioned her to write the official biography of his late brother, King Charles V. This, her first prose treatise, would become The Book of the Deeds and Good Practices of the Wise King Charles V (1404). One can only imagine the jealousy aroused among Christine’s male colleagues at being passed over for a mere woman and “compiler,” from which accusations she defends her historiographical approach and credentials (pt. 1, chs. 1, 2, 21). She also was doubtless thrilled to be able to infuse her personal recollections, though primarily her father’s as royal astrologer at court, of her favorite king. Neither a biography in the modern sense, nor an author’s self-serving encomium, Charles V exemplifies the “princely mirror” genre: it praises Charles’ virtues and exploits but also relates them didactically, for the education of future princely readers (e. g., chs. 13–16). Christine begins by echoing a prayer from the Hours of the Virgin (also Psalm 51:15), asking God: “Open my lips and enlighten my mind” to praise (not God, as in the original) but the king (Charles V, I:1; Walters 2003:33, 40–41). This substitution of Charles for God among his subjects is not so blasphemous as it might seem considering French kingship theory, which, even more than other kingdoms’ views on the divine right of kings, stressed and developed the godlike, even miracle-working powers and continuity of kings (Delogu 2008:153–83). While her earlier princely manual, the Epistle of Othea, provides one hundred exempla, Charles V contains only one exemplum: the king himself.

Christine divides the biography into three parts: 1) nobility of courage (including Christian devotion); 2) chivalry (knighthood, military success); and 3) wisdom (the most completely developed part, since Charles’ epithet was “the Wise,” as evidenced by his love of books, both secular and theological). Her evaluation borrows much from Aristotle and ancient legend in extolling the late king’s religious piety, excellent diplomacy, intellectual and architectural patronage, all characterizing great ancient rulers and heroes. She credits Charles’ profound prudence and piety, with his studious way of life and pursuit of peace. When recounting his death, Christine prays to the Holy Trinity for him and his surviving brother, Duke Philip of Burgundy. This work thus also reads as hagiography; its final chapters more like a sustained prayer, no doubt due to her reliance on the so-called Anonymous Latin Relation’s account of the king’s final moments. Since she minimizes physical details of his death at age forty-six and burial rituals normally included in royal biographies, we may surmise she wished her book to serve as his spiritual reliquary, housing and commemorating his saintly travails and virtues. Likewise, none of the manuscripts of Charles V, even those done at her atelier, contain a miniature portraying the King, which is quite unusual (Ouy, Reno, and Villela-Petit 2012:477–515). Her verbal portrait is how she wished him to be remembered.

After participating in the Rose Debate (discussed below), and then assuming the role of royal biographer, Christine found further reinforcement of her reputation as the literary and intellectual equal to her male contemporaries. This was expressed particularly through her 1404 exchange with the esteemed poet, royal emissary, and legal official, Eustache Deschamps (ca. 1346–ca. 1406), to whom she wrote a laudatory verse epistle, calling him “Eustache Morel,” then (despite her hallmark “simple little woman” persona) addressing him as “friend,” and finally “brother,” and promulgating her idea of the poet’s art and its role in society. Deschamps was a disciple of the illustrious canon Guillaume de Machaut (1300–1377), arguably the fountainhead of French lyric poetry and musical polyphony, so Deschamps’ opinion counted mightily. He soon answered Christine most respectfully, complimenting her as premier woman poet and “muse” of France in his Ballade No. 1242 (Blumenfeld-Kosinski 1997:109–13; Richards 1998:110–22).

Within a year or so of writing Charles V’s biography, Christine de Pizan published The Book of the City of Ladies (1404–1405), her best-known work for our time. It is considered the earliest feminist manifesto, the first known history of women written by a woman. Scholars also view it as a work of feminist theology (Richards 1995; Gower 2015; Gower 2022) that argues for women’s equality under God (pt. 1.9.2). In City of Ladies, Christine presents herself as poet–theologian, as did Dante (Richards 2003:47). Indebted for much of its “historical” material to a French translation of Boccaccio’s Latin De mulieribus claris (Famous Women, 1361–1362), it rewrites the Florentine’s deftly sarcastic, condescending catalog of women, and certain Church Fathers’ detractions, into a serious progressive history seeking to equalize women’s status as humans along with men. Unusually, Christine intended City of Ladies for no specific patron, although it figures in all three of the major manuscripts of her collected works: for the Duke of Berry, Queen Isabeau, and her own copy, “Christine’s Book.”

Cristine’s Vision (1405) extensively develops the autobiographical–pilgrimage aspect, and pertinent allegories, of Christine’s authorial persona previously glimpsed in some of her ballade and other lyric sequences, plus narrative poems like the Path of Long Study, and especially Fortune’s Mutability. Cristine’s Vision is another dream-vision divided into three parts, following a multi-level explanatory preface purporting to gloss Part One, and qualifying this work as both an autobiography and political survival guide. First, after falling asleep, the narrator–pilgrim spirit, “Cristine,” meets Chaos, a fantastic giant, standing beside the even larger, crowned female shadow (Nature), who feeds him and all humankind. Nature “bakes” Cristine into edible form and feeds her to Chaos, through whose entrails she travels with her guardian figures to the realm of Libera (France), who confides to Cristine her many woes, all allegorized: the golden tree of the French monarchy surrounded by raptors, lions, lizards, and worms; such virtues as Reason, Chivalry, and Justice imprisoned by Fraud, Luxuria (lustful self-indulgence), Avarice, and buffeted by the winds of Pride. Because of her realm’s dangerously sinful state, Libera appoints Cristine the agent of reform and salvation to avert divine retribution.

In Part Two in Cristine’s Vision, she journeys to the “university of the Second Athens” (Paris), the Sorbonne, filled with debating clerics and swooping shadows, where she encounters another gigantic, shadowy figure: multicolored Dame Opinion, source of all human error. She, too, recounts her troubles to Cristine, promising to tell her the truth. In Part Three, the final domain atop the Sorbonne’s tower, to whence Cristine is guided by an abbess, is beautiful and bathed in the brightest light (unlike Reason, above, trapped in darkness by Fraud) and sweet voices: here is ensconced Lady Philosophy. This time, it is Cristine who confides her life story, much closer here to a true autobiography of Christine the author than the self-references in her other works. Philosophy comforts her with a long lecture on moral fortitude and wisdom borrowing much, in both structure and citations, from Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy, and quoting heavily from the Fathers of the Church and other later Christian authorities. Cristine thanks Lady Philosophy, whom she now addresses as the more superior Holy Theology (“Sainte Theologie”), in whom all sciences are united to “nourish my ignorant spirit” (Reno and Dulac 2001:140). She compares each part of her Vision to a precious stone: a diamond, a cameo, and a ruby, respectively, as the story ends abruptly (Reno and Dulac 2001:200–07).

Ever aware of rendering her ideas more accessible, a year after her Vision, Christine penned a more down-to-earth, practical version of the City of Ladies titled the Book of the Three Virtues. Historically, it is the first courtesy manual composed by a Christian European woman author and also the first such guide for all social classes and not solely the nobility. It would soon be translated into several languages because of its popularity, as would certain other works by Christine.

More pointedly and urgently given France’s current political crisis, Christine’s Book of Human Integrity (1405–1406), not only pays homage to, but also tries to instruct—indeed, warn—Duke Louis I of Orléans (1372–1407), the younger brother of King Charles VI, the leading contender for the French throne during Charles VI’s madness, to exercise prudence and caution as he was now co-ruling with Queen Isabeau. [Image at right] Christine favored Louis’ political views and refined princely bearing, but feared his brash speech and unscrupulous greed. She believed these qualities would ruin his public image and anger such enemies as his ruthlessly ambitious cousin, Duke John I the Fearless of Burgundy (1371–1419). Her efforts proved in vain, as the otherwise ideal prince was murdered by Burgundy’s men a year after her book came out, further sending the kingdom into chaos.

In 1405, Christine also tried to warn Queen Isabeau, in rather forceful language via her Epistle to the Queen, of her role in the kingdom’s precarious political situation. Christine later feminized Man’s Integrity into The Book of Prudence (1408) for the reputedly dissolute Queen Isabeau, now the ambitious Duke Louis I of Orléans’ co-ruler and alleged consort after her husband Charles VI went mad. Christine obviously wished to remind them to be more prudent. Unfortunately, she could not present Prudence until after Duke Louis’  brutal assassination in Paris in 1407, a crime that touched off the long, violently divisive civil war between the ruling factions of Armagnac/Orléans and Burgundy. Christine hoped that Queen Isabeau and other nobles could benefit from her book to restore peace and order within France. [Image at right]

brutal assassination in Paris in 1407, a crime that touched off the long, violently divisive civil war between the ruling factions of Armagnac/Orléans and Burgundy. Christine hoped that Queen Isabeau and other nobles could benefit from her book to restore peace and order within France. [Image at right]

The Book of the Body Politic (1406–1407) and Book of Feats of Arms and Chivalry (1410), represent Christine’s further efforts toward reforming the nobility to save France, specifically for the education of the Dauphin Louis, Duke de Guyenne (1397–1415), for whom she also composed the Book of Peace (1412–1414). These are loftier, more legalistic, and less personal in tone than her poetry and prose laments. Based on Roman sources (Valerius Maximus and Vegetius, respectively, among others), they also are more secular, although pt. 1: chs. 7–8 discuss the young prince’s religious education. Not surprisingly, Charles V emerges as the ideal leader, a model king, or governmental “head,” in Body Politic, while Feats of Arms aims at the “arms and hands.” By this time Duke John I the Fearless of Burgundy, having eliminated his rival, Louis I, Duke of Orléans, had now won Queen Isabeau’s support, and thereby control of her son the Dauphin Louis de Guyenne, for whose education John probably commissioned Feats of Arms from Christine. Christine’s varied, sometimes politically conflicted patronage (for instance, moving from Orléans to Burgundy) attests to her shrewd adaptability as prince-pleaser, and, she hoped, a prince-reformer. Though dominated by the ruthless John I of Burgundy, Dauphin Louis did manage to negotiate a peace between the Burgundy and Armagnac factions during their relentless civil war destroying France’s body politic, in 1409, 1410, and 1412, perhaps thanks to Christine’s influence. He would die, possibly of dysentery, at age eighteen, in late 1415, to be succeeded eventually by his brother, the future Charles VII of France (1403–1461), as dauphin.

Christine composed her Seven Allegorized Psalms (1409) for yet another French nobleman. Charles III, King of Navarre (1361–1425), needed spiritual reassurance in the wake of a betrayal, which Christine hoped to provide in her version of the Penitential Psalms. Turning to the Penitential Psalms in times of distress was hardly new, but her interpretation of them is. First, she translated Psalms 6, 31, 37, 50, 101, 129, 142 into French from the Latin Vulgate. Her style of allegory here resembles that found in her Epistle of Othea more than the allegories in her Vision, for example, because it seeks to connect teachings from the Old and New Testaments and Christian sources. She also associates France’s destiny with sacred history as another means of reassuring readers in this war-torn kingdom. While other fourteenth-century French and Italian humanists rewrote the Psalms, it was for their personal solace, whereas Christine did so for France’s leaders’ spiritual guidance (Boulton 2003:215–18; Walters 2003:25–41; Margolis 2011:120).

Christine wrote her tearfully passionate Lamentation on France’s Ills (1410) to warn another powerful duke and brother of Charles V, John, Duke of Berry (1340–1416), along with Queen Isabeau, about the further impending horrors of the Armagnac/Orléans–Burgundy conflict, urging them to bring about peace. Pleading as the “lonely little woman on the margins” (seulette a part), Christine also exhorted all levels of government and the clergy to exercise their prerogatives toward this end and urged the French people to recover their moral virtues and civility to strive for peace. An unstable treaty was soon reached by the princes at Bicêtre that same year, perhaps independently, or perhaps because of Christine’s efforts.

By New Year Day 1414, Christine was so confident that she presented Queen Isabeau of  France with an editio princeps (command performance manuscript) of her work thus far. This beautifully executed manuscript has become known as the Harley manuscript 4431, currently in the British Library, London. Seen here is the opening page, complete with a presentation portrait of Christine, center, kneeling in her trademark blue dress and white head covering, presenting her volume to Queen Isabeau, at left. [Image at right] Although Christine’s atelier executed many prized manuscripts, this manuscript epitomizes the workshop’s skill—via both miniature and text—and Christine’s growing prestige. Her works and manuscripts were now in great demand.

France with an editio princeps (command performance manuscript) of her work thus far. This beautifully executed manuscript has become known as the Harley manuscript 4431, currently in the British Library, London. Seen here is the opening page, complete with a presentation portrait of Christine, center, kneeling in her trademark blue dress and white head covering, presenting her volume to Queen Isabeau, at left. [Image at right] Although Christine’s atelier executed many prized manuscripts, this manuscript epitomizes the workshop’s skill—via both miniature and text—and Christine’s growing prestige. Her works and manuscripts were now in great demand.

On the national scene, already weakened by previous military losses to the English during the Hundred Years War, France suffered a further blow at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. Although outnumbered and less-heavily armed, the English under King Henry V destroyed the French army, causing the deaths of many men, including French knights. The English dubbed their victory the “Miracle of St. Crispin’s Day,” which further demoralized the French cause: Did God favor the English after all? Christine, among other moralists, struggled to disprove this possible portent. Her answer would arrive later, in her final work, the Song of Joan of Arc (1429).

But first, she needed to console the widows bereaved by Agincourt in the Epistle on the Prison of Human Life (1416–1418). This prose epistle was dedicated to the daughter of John of Berry, Marie of Berry, Duchess of Auvergne and Bourbon (c. 1375–1434), upon her father’s death. Marie had been kind and generous to the financially struggling Christine years ago, which support this work aims to repay. Its tone more consciously high-oratorical than the Lamentation, this epistle addresses all widows and other bereaved women after Agincourt as a sort of “cure” for their grief. First stressing that mortal life is a cruel prison to be endured with great patience (heart, courage), Christine asserts that Marie’s relatives and all the other slain French knights will go to Paradise. She goes on to aver that God’s vengeance will punish the wicked, as attested in ancient pagan and biblical history. Meanwhile, the civil war between the forces of Armagnac/Orléans and Burgundy ravaged Paris in 1418, reigniting the Hundred Years War.

Further tragedy affecting Christine occurred when her son, Jean de Castel, died in 1425. Jean had returned to France about 1409 to serve as notary and secretary to various nobles, including King Charles VI, and may also have joined his mother’s atelier as a major copyist. Scholars believe her maternal sorrow at least partly motivated her to compose her Hours of Contemplation on Our Lord’s Passion (Margolis 2011:123).

Christine’s last known work is The Song of Joan of Arc (July 31, 1429). This patriotic poem celebrates the narrator’s boundless joy (after so many years of national and personal tribulation and loss) elicited by the long-awaited victory of the French over the English on May 8, 1429 at Orléans, and the recent coronation of the Dauphin at Reims. Led by the passionate visionary Joan of Arc, age seventeen and clad in armor, it appeared to be a French miracle to avenge the English victory at Agincourt. From there, Joan would go on to Reims to see her dejected, exiled dauphin rightfully crowned King Charles VII, who would complete the task of expelling the English from France and return the country to glory. Despite the poem’s spontaneity and orality, Christine still deploys her vast learning to advantage. First, rather as Joan herself had to do to win the Dauphin’s confidence in her as divinely appointed savior, Christine presents her own credentials as poet-prophet. She cites pagan and biblical precedents for women saving their people in “masculine” fashion, such as the Amazons, Judith, Esther, and Deborah. Both assumed male garb in a way: Joan for military purposes, as commanded by her voices, while Christine did so professionally, as allegorized in her Fortune’s Mutability. Christine defends Joan as divinely inspired through her voices and visions of saints Michael, Margaret, and Catherine. “Aha! What an honor for the feminine sex!” (Song of Joan of Arc, stanza 34, vv. 1–2), Christine exults, as if a heroine from her City of Ladies had burst into life. While Christine, however, likely did not see Joan in person while she traveled to the Reims coronation, Christine’s friend Jean Gerson had earlier met Joan at Poitiers, in his capacity as chief theological examiner of her prior to the Dauphin’s sanction of her mission leading his armies against the English. Gerson probably informed Christine of this inquiry’s findings. Contrary to her poem’s modest title, Christine forcefully defends the Maid against embittered Anglo-Burgundian propaganda disseminated after she defeated them. For example, Joan’s unusual qualities, such as wearing armor and carrying a special banner, are not satanic in origin, but rather divinely mandated, like her portentous voices and visions. Christine goes on to emphasize that the victory at Orléans was no fluke and Joan is no witch. Charles VII was the rightful king of France, not Henry VI, despite English political machinations. Finally, it is the French who are God’s chosen, not the English and their Burgundian allies, the latter among whom will be cursed if they do not switch their loyalty back to France, which they did after Joan’s death in 1431, as part of the heroine’s “rehabilitation,” proclaimed in 1456. That few manuscripts of Christine’s Joan of Arc were executed suggests that it was intended mainly for public reading to celebrate Joan as she and her army rode through various towns.

Little is known of Christine’s death. It is believed that she died at Poissy, where she is commemorated nowadays by an Avenue Christine de Pizan. It is known that she died after July 31, 1429. One hopes she passed away before May 30, 1431, when Joan of Arc was burned as a heretic by the English. Christine would have died at age sixty-six or sixty-seven.

TEACHINGS/DOCTRINES

Christine’s feminism favors both men and women (Brown-Grant 2003). It is rooted in her female-centered theology, based on the same Church Fathers and Church Doctors so often cited for arguments against women, such as when she interprets Paul in 1 Corinthians 11:1–15, allegorically and anthropologically, to prove that women and men are both made in God’s image and dedicated to His glory (Gower 2022:185–207). Her City of Ladies therefore not so much refutes such stereotypical interpretations of authors as St. Paul, as it reinterprets these received ideas to women’s advantage. Other Church Doctors, namely Peter Lombard (1100–1160) and Hugh of Saint Victor (c. 1096–1141), had already stressed the equality of women and men in creation, and thereby provided a basis for Christine’s defense of women. She likely had read these Church authors in Latin excerpts from such popular preachers’ compendia as Thomas Hibernicus’ Manipulus florum (Bouquet of Flowers, 1306), and such annotated translations commissioned by King John II of France (1319–1364), or his son King Charles V, as Raoul de Presles’ 1375 French version of Augustine’s De Civitate Dei (City of God) (Richards 1995:290–91).

In most of her works, especially her Vision, she emphasizes the active political uses of morality and spirituality (Reno 1992:221), making this work a mirror for princes, as much as Christine’s autobiography (Brown-Grant 1992). It culminates in Lady Theology emerging as the highest form of all wisdom, just as Christine expressed increasing devotion in her later career.

The Debate of the Romance of the Rose (1401–1404) exemplifies how Christine confronted the Parisian male intellectual establishment. In her letters to these learned, esteemed men, she vehemently criticized the Romance of the Rose they so admired. This work, a dream-vision poem of a naïve young man’s education in proper courtly love begun by cleric Guillaume de Lorris in 1225–1230, but left unfinished, was later jarringly “continued” by the irreverent, learned Jean de Meun (ca. 1269–1278), who added two–thirds (15,000 vv.) more to the work’s total length. The young man narrates his education in wooing, and, with the help of various allegorical mentor figures (gentler and more conventional ones in Lorris’ section; then cruder, cleverer, and iconoclastic in Meun’s) manages eventually to seduce his beloved, symbolized by the rose. The Romance of the Rose not only became a major source of allegorical models for representing earthly and divine love and adversarial emotions, but also musters all medieval learning (history, science, and philosophy) to fuel the pertinent pros and cons of the amorous experience. Lorris is more sweetly idealistic (so much so that he likely abhorred the idea of his lover plucking the rose: perhaps why he could not complete his poem), while Meun’s verses teem with misogynistic stereotypes deployed satirically with multiple learned allusions. Like her contemporaries and followers, Christine mined this encyclopedic quest narrative for material for her own works, despite her opposition to Meun’s cynical ideas on love (which he viewed simply as nature’s trap to encourage procreation) and on women. Christine and Gerson for these reasons deplored his lack of moral responsibility toward the reader.

It was Christine who ignited the actual conflict by writing fervently against an epistle of Jean de Montreuil (1354–1418), a pro-Rose intellectual, that enthusiastically praised the Romance of the Rose to a colleague. As was the practice at the time, this debate consisted of letters exchanged within a small, elite circle: Christine versus several royal notaries, diplomats, magistrates, church officials, and university professors. Although she knew Latin, Christine wrote only in French, while her co-debaters wrote in Latin. Despite her self-presentation as a “simple, solitary little woman,” her anti-Rose epistles boldly pressed the intellectually prestigious pro-Rose faction on their moral irresponsibility, as did her most respected ally, Jean Gerson (Brown-Grant 2003). Though both Christine and Gerson themselves understood Meun’s often biting satire, they feared less sophisticated readers would take Meun’s irony seriously and become confused, and even corrupted, by it. Christine advocated for Dante over Meun as an equally learned and accomplished, but more spiritual and moral, author who revered women. The debate, though never resolved, would establish Christine as a public intellectual capable of holding her own among elite male clerics and notaries, while remaining philosophically independent. It also enabled her to sharpen her prose polemical skills at expressing themes traceable to her earliest lyric poetry, here now in prose. Her prose debate epistles complement her two independent verse epistles on the same topic: the God of Love’s Epistle and Tale of the Rose. As a final phase to her strategy, she presented a copy of all debate participants’ letters to Queen Isabeau, which likely made the pro-Meun faction uneasy, lest the Queen find out how such high-ranking civil servants used their spare time.

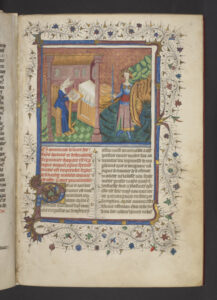

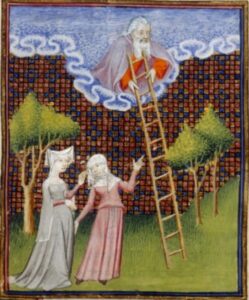

Christine’s desire to demonstrate the moral superiority of Dante’s Divine Comedy to Jean de Meun’s Rose yields another significant phase in her teachings—her Book of the Path of Long Study (1402–1403), whose Dantesque influence is signaled by its very title, echoing his Inferno I: 82–84. Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy (523 c.e.) serves as another major source. Christine deftly interweaves elements of Dante’s allegorical journey from Hell through Paradise (guided first by Virgil and then by his beloved Beatrice) with aspects of Lady Philosophy’s exchanges with the unjustly condemned Boethius. In th e Path, the ill-fated Boethius is now the unjustly unfortunate Christine, as she converses with her guide, Amalthea (“Almethee”), from Virgil’s Cumaean Sibyl guiding Aeneas’ Underworld journey in the Aeneid, bk. 6. This narrative-verse poem begins with Christine’s lament of her misfortunes, whereupon she falls into a dream state and experiences a didactic,consoling pilgrimage vision. Amalthea appears to her and invites Christine–Pilgrim on a privileged journey (like Aeneas and Dante), revealing to her many of the world’s marvelous places from biblical and classical-antique legend. Amalthea then leads her upward through Earthly Paradise, aided by the Ladder of Speculation, all the way to the firmament (Fifth Heaven), from whence she teaches Christine about the mysteries and harmonies of the planets in space. [Image at right]

e Path, the ill-fated Boethius is now the unjustly unfortunate Christine, as she converses with her guide, Amalthea (“Almethee”), from Virgil’s Cumaean Sibyl guiding Aeneas’ Underworld journey in the Aeneid, bk. 6. This narrative-verse poem begins with Christine’s lament of her misfortunes, whereupon she falls into a dream state and experiences a didactic,consoling pilgrimage vision. Amalthea appears to her and invites Christine–Pilgrim on a privileged journey (like Aeneas and Dante), revealing to her many of the world’s marvelous places from biblical and classical-antique legend. Amalthea then leads her upward through Earthly Paradise, aided by the Ladder of Speculation, all the way to the firmament (Fifth Heaven), from whence she teaches Christine about the mysteries and harmonies of the planets in space. [Image at right]

They then descend back toward earth, pausing at the first heaven to observe all the (mostly  negative) forces controlling earthly life: Love, Hatred, Fear, and Fortune. Soon thereafter, Christine witnesses a debate among four allegorical enthroned ladies: Wisdom, Nobility, [Image at right] Chivalry (feats of arms), and Wealth. A fifth throne, at first empty, belongs to Reason.

negative) forces controlling earthly life: Love, Hatred, Fear, and Fortune. Soon thereafter, Christine witnesses a debate among four allegorical enthroned ladies: Wisdom, Nobility, [Image at right] Chivalry (feats of arms), and Wealth. A fifth throne, at first empty, belongs to Reason.

More positive, less cynical, than Jean de Meun’s version of her in his Rose, Christine’s Reason is frustrated by humanity’s neglect of her, and at Wisdom’s passivity, hence much of the world’s trouble. The four ladies’ first topic is how to prevent the spread of evil and corruption in the world. After squabbling pointlessly over this, they then attempt to determine which of them most befits an ideal monarch, again without resolution after a scene recalling the Apple of Discord, disputed by Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite, from classical Greek myth. Yet in Christine’s Path they do decide, with the help of Reason’s wise proxy, Opinion, to defer this judgment to the most sagacious of earthly courts in the earth’s most worthy kingdom, France. Christine is named official notary of that court’s decision. Reason approves her transcription and Christine is sent back down to earth, to the French court. This ending becomes more meaningful when we consider that Christine wrote the Path for King Charles VI of France, and dedicated it to his uncles, the “noble dukes” (in truth, the avaricious power mongers she hoped to enlighten) while attracting their patronage. Overall, the Path relates a spiritual journey to find a political solution. Christine–narrator will converse more thoroughly with Reason in her City of Ladies, and more directly with Philosophy and other female authority figures in a Boethian or Dantesque vein in her prose Christine’s Vision (1405).

Yet another work, The Book of Fortune’s Mutability (1403), reveals Christine’s hagiographical instruction. Medieval history often did not differentiate between actual history and legend or myth, as reflected in Christine’s sources and references. Nor had medieval authors yet learned to distinguish between an ancient author’s original, primary texts, and digests of such authors in medieval compendia, usually translated, excerpted, or paraphrased. As a major example, when late medieval authors cited the Roman poet Ovid’s very pagan Metamorphoses (first century B.C.E.) or Greco-Roman mythological tales, it was usually in fact the Ovide moralisé, an extensively Christianized version in French (early fourteenth century). This translation, like its original but more accessible, provided a model for depicting physical transformation symbolizing spiritual change with divine help. But for Christine and the Ovide moralisé, “divine” meant God instead of Ovid’s Jupiter and other Roman deities. Nevertheless, a few deities such as Fortune (Fortuna) persisted to explain God’s less predictable ways, up through the Reformation era.

As a survivor of numerous “mis-Fortunes,” Christine tells us that she will confront Fortune in hopes of learning how to serve, and thus govern her (v. 107). She alludes to her own mother in strictly allegorical terms, as all-powerful “Nature,” who has endowed her daughter with a protective jeweled crown imparting all facets of wisdom (Fortune, vv. 523–640). This complements the other “treasure,” the exceptionally fine education she received from her brilliant father, whom she claims to resemble physically in every way but gender, which proves useful in recuperating from his and her husband’s poor management of his material treasure (vv. 379–451). But above all, even above Nature, she thanks God as creator and bestower of all virtues (vv. 662–69). Gender transformation most intrigues Christine, as when, in Part 1, she cites Ovid’s tales of Tiresias (Fortune, vv. 1060–1112) and Iphis (Yplis) (vv. 1115–58), as if to prepare us for her own impending metamorphosis. She evokes her untimely widowhood by alluding to another Ovidian tale, the beautifully moving Ceyx and Alcyone story (vv. 1251–64). Christine-narrator begins with a quasi-autobiographical account of her marriage as a smooth-sailing vessel suddenly destroyed by a violent storm that sweeps away her husband. This leaves Christine to navigate her life’s ship frightened and alone. Fortune, out of either compassion or whimsy, transforms her into a man in a dramatically detailed scene (Fortune, vv. 1313–1416), symbolic of her real life. Theologically, she also upends Adam’s biblical supremacy, since here she portrays herself as a man sprung from woman (Richards 2003:48). Thus empowered, Christine visits Fortune at her immense turning castle of Great Peril, perched upon a frozen rock surrounded by ocean. Christine hopes to educate herself in the goddess’ ways, as part of her passionately omnivorous education in real life (Rider 2018:39). Thanks to her newly acquired crown from her symbolic mother, Nature (proving that knowledge derives from feminine sources as well as masculine ones) Christine feels ready to surmount her fear and benefit from what she will see inside Fortune’s castle at the beginning of her new-life journey as a man of “strong and bold heart” (v. 1359), while retaining her mother’s equally essential feminine morality (vv. 1446–47) (Huot 2021:145).

Part 2 of Fortune describes the castle’s complex structure and setting, replete with numerological allegories, usually in groups of two and four. In Part 3, Christine narrates and comments on the vertical hierarchy of “sieges et condicions” (thrones and situations) of society and cosmos, from mortals to heavenly beings: all beautifully depicted in miniatures of the best manuscripts of Fortune. She is also one of the very few authors ever to mention and even sympathize with the poor, including lower-class women and widows. Part 4 first celebrates the various branches of medieval knowledge (Grammar, Rhetoric, Mathematics, Astronomy, and so on), culminating in Theology, which encompasses all branches of learning at the highest, “celestial” level.

Christine then launches into her chronological history of the world as then known, from Genesis and later Old Testament events through to her own time, as she studies the historical illustrations housed within the “Marvelous Room” within Fortune’s castle. The figures in the paintings come to life during Christine’s expositions of different cultures’ histories. She narrates all in verse until she comes to the history of the Jews. Pleading illness and the need to keep to her schedule, she composes this section exclusively in prose, supposedly for greater ease, but perhaps also out of conventional prejudice. After completing these last paragraphs of Part 4, she returns to verse in Part 5, describing the evil effects of envy and greed upon civilizations such as the Assyrians, Persians, Egypt, Babylon, Greece. Part 6 continues the history of the Greeks, again based on legendary and mythical heroes and heroines rather than the historical figures known to moderns. Part 7 devotes itself to Roman history, typically based more on myth and literature than on actual history per her sources, such as the anonymous French compilation, Ancient History until Julius Caesar (1200s), although Julius and Augustus Caesar are mentioned.

Christine then effects a quantum leap, bypassing Rome’s fall (404 C.E.), the reigns of Charlemagne (Holy Roman Emperor from 800 to 814) and Louis IX (1214–1270), King of France also known as Saint Louis, among others. In other words, she skips the first through thirteenth centuries jumping into her own time, centering primarily on France, with some passages on Italy and England. In so doing, Christine demonstrates that her adoptive France, even over her native Italy, is the rightful successor to the glory of ancient Greece and Rome. Although this theme of transcultural legacy through learning (translatio studii) was already a common one, Christine herself, self-styled as France’s Minerva (the wise warrior goddess also born in Italy, as Christine proclaims in Feats of Arms, 13 and n. 2), will also help guide France toward this legacy. Through her writings, she will advise French rulers in how to control, or at least confront, Fortune’s ways, in the interests of peace and harmony.

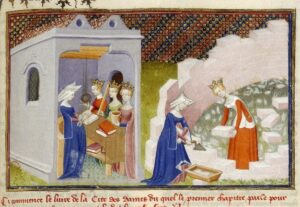

The most famous and influential of her many writings is undoubtedly The City of Ladies (1404–1405). In that book, Christine–narrator begins by showing herself reading the Lamentations of one Mathieu of Boulogne (1260–1320) (also called Matheolus) a stereotypically misogynistic would-be theologian, whose laments target women for all their supposed evils, inadequacies, and deformities, both moral and intellectual. Although Matheolus is himself a nondescript mediocrity, his pronouncements nevertheless depress Christine because far greater minds espouse similar ideas, from Aristotle (and thence to Thomas Aquinas, Aristotle’s thirteenth-century Christian Latin interpreter) to John of Salisbury in his Policraticus (twelfth century, translated into French in 1372), Boccaccio (1350s–1360s, translated into French 1375, 1403), and Jean de Meun who were otherwise inspirational sources for her (McLeod 1992:38−41).

Overcome with sadness, she falls asleep and then experiences a dream vision, in which she is visited by three female allegorical figures: Reason, Rectitude (right-thinking, acting), and Justice, who, like Philosophy to Boethius in his Consolation, comfort her in her chagrin. In a scene reminiscent of the Annunciation (Walters 2006:240; Kolve 1993:171–96), appearing in a ray of light, the allegorical women first chastise her for despairing, then command her to redeem the status of women by truthfully revising their history, devoid of male-clerical misogyny, to be structured as a citadel, each of whose three parts is to be governed by one of the three allegorical ladies. This mission bears markedly Augustinian echoes, for just as St. Augustine would attempt in the City of God to defend the Christian Church against erroneous accusations that it caused the fall of Rome, so Christine, in her City of Ladies, would counter misogynistic beliefs that woman caused the Fall of Man (Humanity) (Margolis 2011:70). Moreover, she goes beyond merely defending them, as symbolized by the “city” (fortress) metaphor all the way to asserting women’s equality (Mann 2013:1). Another striking analogy inspires Christine’s City: just as St. Peter, then other saints, represent “living stones” of Jerusalem in the New Testament (Psalm 126; 1 Peter 2:4–7), so each great woman’s life is symbolized by a brick or stone and mortared into its relevant section of the citadel and the book itself (Richards 2003:45–46).  Thus Part 1, Reason’s domain, harbors queens, warriors/Amazons, builders, and learned/skilled women. [Image at right] Part 2, Rectitude’s realm, houses sibyls, prophets, and other visionary women; secular heroines of chastity, integrity, honesty, learnedness, patience in love—in response to male selfishness, stupidity and brutality. Part 3, ruled and narrated by Justice at the City’s loftiest level: religious women, saints and martyrs, beginning with the Virgin Mary, queen of Heaven and here, queen of this new realm of women. This part contains the most graphic depictions of physical violence and suffering in the whole book, as if to show that women equal men not only intellectually and morally but also in Christian devotion and suffering. It forms the culmination of Christine’s re-ordering and rewriting the lives of women from throughout history to show them as glorifying God and being in his image—not as an imperfection. Women can be as intelligent and virtuous as men. They can also teach and perform apostolic work.

Thus Part 1, Reason’s domain, harbors queens, warriors/Amazons, builders, and learned/skilled women. [Image at right] Part 2, Rectitude’s realm, houses sibyls, prophets, and other visionary women; secular heroines of chastity, integrity, honesty, learnedness, patience in love—in response to male selfishness, stupidity and brutality. Part 3, ruled and narrated by Justice at the City’s loftiest level: religious women, saints and martyrs, beginning with the Virgin Mary, queen of Heaven and here, queen of this new realm of women. This part contains the most graphic depictions of physical violence and suffering in the whole book, as if to show that women equal men not only intellectually and morally but also in Christian devotion and suffering. It forms the culmination of Christine’s re-ordering and rewriting the lives of women from throughout history to show them as glorifying God and being in his image—not as an imperfection. Women can be as intelligent and virtuous as men. They can also teach and perform apostolic work.

Christine’s descriptions and illustrations demonstrate the advantages of directing her own atelier. By directly supervising many of her manuscripts’ miniatures (illustrations) as well as their texts, she controlled how they reinforced her message. Thus, her images’ focus on hair and head-coverings, for example, complement her texts’ case for paternal relationships and women’s equality to men as God’s creation (Gower 2022).

The City’s final chapter, however, disappoints modern feminists because it counsels wives of abusive husbands to try to reform them. Failing this, they should passively and patiently tolerate bad treatment for the good of family harmony and social reputation. And these wives’ reward will come in heaven (City pt. 3.19.2–3), Christine reassures us, in echoing the Magnificat (Luke 1:46–55), just as we witnessed in the City’s beginning, channeling the Annunciation. Christine’s primary model throughout this work, over all the great heroines, secular and religious, is the Virgin Mary, in her piety and prophetic voice (Walters 2006).

The Livre des trois vertus (Book of the Three Virtues) (1405–1406), for example, is a practical manual for a virtuous woman’s life, based on the heroic examples in City of Ladies. The Three Virtues may be seen as a pedagogical extension of the heroic moral lessons of City of Ladies for everyday use by ordinary women of all social classes and situations seeking to lead good lives. Christine thus translates the City’s exalted guiding virtues of reason, rectitude, and justice into the more accessible wisdom, prudence, and piety in Three Virtues, for wealthy, then middle-class urban women, and then even down to prostitutes. Every woman must protect her honor. Sensing that most women cannot expect to become famous heroines, intellectuals, artists, or martyrs as found in the City of Ladies, Christine instructs them in Three Virtues on how to improve their lives as much as possible by emulating virtuous women given real-life limitations, through a kind of everyday heroism. There are no monsters or armies to slay in Three Virtues; just exercising financial know-how and discreet, modest conduct and dress to protect a woman’s honor and her family’s reputation against society’s evils: poverty, hypocrisy, fraud, theft, and slander. Indeed, quietly virtuous mothers, wives, single women (more than flamboyant heroines and martyrs) form the basis of a productive, harmonious, and peaceful society. Although it may perplex modern readers that she devotes two-thirds of the Three Virtues to aristocratic and upper-bourgeoise women, this is because they wielded more power and influence, good and bad (Krueger 2003; Krueger 2018).

As Othea, Fortune, City of Ladies, and other works demonstrate, Christine deftly used a wide range of classical, biblical, and theological sources. Because she was female and thus an outsider, she needed more “ammunition” to attain the credibility of established male authors. She therefore abundantly infused her works with a multitude of theological, scientific, and historical authorities to bolster her case: the amplificatio technique. But she always added a new twist to classic, male-centered dogma, or a new context for well-worn sayings. She learned to transform her original disadvantage as a solitary, struggling woman writer into privileged marginality to effect positive sociopolitical change.

Yet Christine’s ideas, like those of her ideal king, Charles V, are not flawless. Her worst offense lies in her apparent antisemitism, as demonstrated most strikingly in Fortune (pt. 2, ch. 4), and also in Charles V, Feats of Arms, and Hours of Contemplation (Fenster 2020). The beliefs she expresses in these texts were quite commonplace in her time; but then, so was misogyny. However, she was able to show that misogyny had no place in a truly Christian society, whereas she failed to make the same case about antisemitism. Moreover, due to the expulsion of the Jews from France in 1394, she would likely never have known any Jews personally.

In her religious works she generally speaks in the first person, as she does in most of her lyric and narrative works. When speaking as “moyenarresse” (female intermediary), however, her spiritual “I” evolves beyond mediation to direct representation of her readers to help them experience the ultimate level of suffering in Christ’s Passion, especially in her Hours of Contemplation. A potentially brazen departure from sacred texts is Christine’s slight altering of the Gospels, as when she shows Mary’s foreknowledge of her son’s untimely death (Hours). But this again derives from her personalization of sacred sources rather than blasphemous presumption, all to draw closer to her reader, not simply as intermediary, as in her earlier works, but now as her readers’ representative, the poet at prayer (Boulton 2003:224–25).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The main form of devotion for Christine de Pizan functioned through intensifying emotion, or affective piety (Boulton 2003), inspired by exegetical reading of sacred texts. Exegetical reading resembles mounting a ladder, each of whose three (as in Othea’s Epistle) or four rungs yields deeper meaning to arrive as close to divine perfection as possible.

Perhaps one of the clearest forms of pious writing was Christine’s Hours of Contemplation on Our Lord’s Passion (1418–1428). Although no one knows its exact date of composition, the text addresses the losses incurred at Agincourt. One of the rare devotional treatises written by a layperson, it resumes the medicinal metaphor of Prison of Human Life, this time expanding her audience from aristocratic widows, to the “devout sex of women.” Her tone, showing the influence of her friend Jean Gerson, is that of both solitary preacher and prophet: teacher and visionary (Walters 2008; Autrand 2009; Dulac and Stuip 2017). As a supposed Book of Hours, it is structured according to the seven Canonical Hours (oddly enough, beginning with the last: Compline), each containing a Latin verset from Psalm 69. Although she quotes St. Augustine and St. Bernard, the book is patterned more closely on Pseudo-Bede’s Latin Meditation on the Seven Daily Hours of Christ’s Passion (early fourteenth century) (Boulton 2003:223), and even more, upon her friend Jean Gerson’s French Little Treatise on the Death and Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ (Dulac and Stuip 2017:xxxii–xlvi, 175–202). It is possible that her meditation-service was written upon the death of her son Jean in 1425, hence her highly personalized co-suffering with Mary and then Christ himself (Willard 1994:202–03). In so doing, Christine is not being presumptuous, but rather she seeks to universalize and sanctify the pathos of maternal suffering over the loss of a son or daughter.

Christine taught by example, living in the world as an honorable, Christian woman in accordance with her Three Virtues (West 2009). She advised men likewise in her Feats of Arms. In other words, she practiced what she preached toward both genders.

Christine was a lifelong devout Catholic, well-versed in liturgy and other ceremony, as reflected in her religious works discussed above. We have seen how affective piety also flourished at this time, as reflected in her privately emotional, as well as more public ceremonial, devotion. Especially in her last twelve to thirteen years at the Poissy priory after 1418, she likely lived as a nun, observing the canonical hours for prayer, in between writing and meditation. Yet she never fell out of touch with key historical events around her, as reflected in her highly spontaneous Song of Joan of Arc. She introduces that work as a joyous personal–political rapture after “eleven years of weeping in a closed abbey,” for her [Joan], the Dauphin, and France.

LEADERSHIP

Christine’s most striking manifestation of leadership arguably lies in her atelier, her own “publishing house,” established and directed by her during the early 1400s. Comprising at least twenty-six workers (three main copyists including herself and possibly her son Jean), more than twelve artisan decorators, eleven illuminators (artists executing miniatures), Christine’s “company” produced some fifty-four extant, mostly deluxe manuscripts in which she functioned as copyist (an extraordinarily high number) of which the Queen’s (or Harley 4431) manuscript is the most prized (Ouy, Reno, and Villela-Petit 2012:316–43). Christine had to purchase parchment, vellum, ink and quills at the most feasible prices while maintaining quality. Then she also had to deal with the binders in properly assembling each manuscript book as the final stage in the text’s journey before presentation to the patron (Villela-Petit 2020:53–60).

Unlike monastic scriptoria, run more like factories, with all copyists working together side by side, Christine’s staff enjoyed more independence and flexible hours, so long as they turned in their sections on time for her to revise and inscribe further instructions in them concerning placement of illustrations and rubrics. Occasionally, parts of the manuscript had to be farmed out to another shop to meet deadlines and budgets. Although Christine tried to hire women whenever possible, the only attested female is the artist Anastaise, whom she praises in her City of Ladies (pt. 1, 41). But Christine held all of her workers in the highest regard, and deservedly so, since pages and details from Christine’s manuscripts often figure in art history books and articles. Her atelier thus enabled her to control the quality and exposure of her works. Sometimes, when a work was being offered to multiple patrons of different political persuasions, Christine would subtly alter each copy of the text to suit each patron’s taste (Ouy, Reno, and Villela-Petit 2012:691–93).

Despite her calculatedly humble persona, Christine embodied a succession of firsts and leadership roles in women’s writing and thought. In her Tale of the Rose, commanded by the God of Love, she founds the “Order of the Rose” to correct the biases of courtly love and counterbalance various male chivalric orders. She became the first systematic feminist, the first French author to incorporate Dante, the first woman to write war treatises, the first European woman to author a courtesy book for women, and the first moralist to include the lower classes in her instructions and teachings.

In France’s first literary debate, the Debate of the Romance of the Rose (which also passed as a debate on women in what would become a long tradition), Christine showed herself capable of controlling the narrative against the most formidable male intellectual adversaries in her letters to them (Hult 2018). Slightly later, she would write to Eustache Morel/Deschamps (Epistle to Eustache Morel, 1404) as an equal, to which the revered poet would respond more positively than the Rose defenders. In addition, we find the most powerful French noble, Duke Philip II the Bold of Burgundy, inviting Christine (and none of her male contemporaries) to write the official biography of his late older brother, King Charles V.

As a feminist theologian and activist, Christine wrote directly to heads of state, even to the queen of France, to urge them to implement peace and progress. She also gained the support of significant male theologians, such as Jean Gerson, as well as royal patrons. Her influence echoed throughout later centuries, especially the seventeenth and eighteenth, in which literate, witty women played greater social roles and, of course, from the twentieth century onward (Margolis 2011:154−56).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Christine de Pizan compares her own destiny, to achieve and suffer for others, to that of Christ, as foretold in her name, which she parses as “Christ-ine” (Fortune, vv. 365–78). She then, daringly, self-identifies with Mary, mother of Christ, to effect further change, and especially peace, in her later works. These were two key personae in her approach to meeting challenges.

A significant problem she sought to overcome was misogyny, permeating all realms and levels of society, to the detriment not only of women but to social harmony and productivity itself. In reforming social and clerical attitudes toward women, Christine’s major step was to rewrite the brilliant Jean de Meun’s Romance of the Rose in both substance and volume, attempting to drown him out of literary history with alternative morally responsible attitudes, without sacrificing great learning and literary vision. Here, her familiarity with Dante served her well.

Although the major Crusades had ended in 1291, their legends persisted, as did St. Thomas Aquinas’ Just War theory (Summa theologiae, 2-2, q. 40). Christine herself wrote two treatises on warfare, but affirmed that, while certain wars may be holy and just, such as the Hundred Years War to save France, they cannot be an end in themselves. Peace is far holier, guaranteeing unity of personhood and thus of society, not only in her Book of Peace but also other works (Gower 2015).

In all, Christine’s entire career consisted of enormous challenges and her attempts to remedy them. Not only was it a man’s world, but a war-torn one, which menaced France’s very identity as a future nation. Thanks to her father’s nurturing erudition and her supportive husband, she grew up unafraid to challenge men on their own terms, whether ancient philosophers, current nobles, intellectuals, poets, and legal officials to claim her due. Despite much suffering, she never saw herself as a martyred woman. Like Joan of Arc, she experienced visions, but unlike many mystics, she and Joan both made their visions a reality as much as possible by effecting change.

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGION

Unlike many of her modern feminist counterparts who perceive the Church Fathers as “the enemy,” Christine incorporated Christian theology, rather than rejecting it, as well as classical–antique sources, into her defense of women as equal partners to men. This is evident in all aspects of her oeuvre: lyric poetry, prose, and devotional literature. Her approach, like that of her male colleagues, of using classical and early Christian texts to find solutions to current problems, marks her as the feminine voice in French humanism. While her male colleagues, more knowledgeable in Latin and later, Greek, could consult original sources as did their Italian contemporaries, Christine was, along with Gerson, prescient enough to incorporate classical-humanistic ideas into serious vernacular expression. As a result, their work reached a wider, more lasting audience, while that of their strictly Latinizing contemporaries faded. This was especially important for her feminist and theological ideas, which were widely read in later centuries. Her defense of Joan of Arc is her culminating work. This was Christine the woman poet’s most direct chance to influence politics and human events; there was no need to convince a noble patron first. Her powerful interweaving of sacred history, autobiography, feminism, and the fate of France mark her as a true historical agent. She was no longer a simple, stoical femmelette to whom history simply happens. In that regard, Christine de Pizan was a truly modern religious woman.

IMAGES**

**All images are from British Library manuscript “Harley 4431,”and all miniatures are by the artist known as the City of Ladies Master, unless otherwise noted. All images published here are courtesy of the British Library.)

Image #1: Christine de Pizan as “seulette” (lonely little woman) in her study or cell, one of several in her manuscripts modeled on such familiar male author portraits as that of St. Jerome in his study. Detail prefacing her One Hundred Ballades, f. 4r.

Image #2: Sample full page from the Epistle of Othea, showing visual-didactic technique: the “gloss” and “allegory” completing the story of Minos (Story 4), then the “text” and miniature introducing the story of Perseus (Story 5), astride winged Pegasus, rescuing Andromeda from the sea monster, f. 98v. Perseus usurps Bellerophon as Pegasus’ rider due to the inaccurate Ovide moralisé version, Christine’s source.

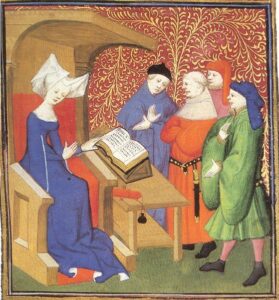

Image #3: Christine instructing and disputing with male colleagues, introducing Moral Proverbs, f. 259v.

Image #4: Christine in her study composing her Feats of Arms and Chivalry, visited by Minerva, “goddess of arms and chivalry.” BL MS Harley 4605, f. 3. Because this manuscript was executed by another artist in 1434, thus after Christine’s death, this miniature’s style differs from that of the City of Ladies Master in Harley 4431.

Image #5: Christine presents her complete works as of 1414, in the “Queen’s Manuscript,” to Queen Isabeau of France, surrounded by ladies in waiting, frontispiece.

Image #6: Christine and Sibyl Amalthea prepare to climb the Ladder of Speculation, provided them by a “strange figure” (male) in the Path of Long Study. f. 188v.

Image #7: Continuing the Path of Long Study, Amalthea instructs Christine in the wonders of the Firmament or “Fifth Heaven,” high above earth, even Olympus. f. 189v.

Image #8: Christine, after visitation by Reason, Rectitude, and Justice in her study, joins Reason in constructing the ground level of the City of Ladies, f. 290r.

REFERENCES

(English translations of Christine’s works listed in Supplementary Resources below. For more original Middle-French editions, see bibliographies in Margolis 2011 and other works.)

Autrand, Françoise. 2009. Christine de Pizan: Une femme en politique. Paris: Fayard.

Blumenfeld-Kosinski, Renate. 1997. The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan. Translated by Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Kevin Brownlee. New York: W. W. Norton.

Boulton, Maureen. 2003. “‘Nous deffens de feu,…de pestilence, de guerres.’ Christine Pizan’s Religious Works.” Pp. 215-28 In Christine de Pizan: A Casebook, edited by Barbara K. Altmann and Deborah L. McGrady. New York: Routledge.

Brown-Grant, Rosalind. 2003. “Christine de Pizan as a Defender of Women.” Pp. 81–100 In Altmann and McGrady, Christine de Pizan, edited by Barbara K. Altmann and Deborah L. McGrady. New York: Routledge.

Christine de Pizan. 2012. “A Sweet Thing Is Marriage.” Other Ballades, 26. Translated by Brandon. Accessed from http://branemrys.blogspot.com/2012/05/sweet-thing-is-marriage.html on 1 May 2024.

Delogu, Daisy. 2008. Theorizing the Ideal Sovereign: The Rise of the French Vernacular Royal Biography. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.