OUR LADY OF FÁTIMA TIMELINE

1858: A Marian apparition occurred in Lourdes, France, which became well known to the seers (or visionaries) of Fátima and might have inspired them.

1910 (October 5): The Portuguese monarchy ended and the declaration of a Portuguese Republic was issued.

1911: The republican government introduced laws of separation of church and state and a series of anticlerical measures, which alienated the country’s mostly rural, poor majority.

1916 (August 16): The parliament of the Republic of Portugal decided to participate in World War I on the side of the Allies, which led to anxieties among the rural, more religious population.

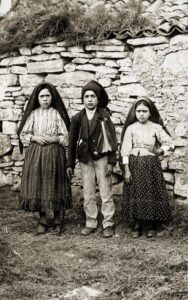

1917 (May 13): The first of a series of monthly apparitions of St Mary, Mother of God. The visionaries were three young shepherds (Lucia, eleven, and her younger cousins Francisco, ten, and Jacinta, eight) in a field near the village of Fátima. More apparitions followed (June 13, July 13, September 13).

1917 (August 13): The local administrator, a secularist representative of the Republic, arrested the three children and threatened them. But the attempt to violently suppress the apparitions only led to more interest and support from the local population and Catholic believers.

1917 (October 13): The “Miracle of the Sun” took place in Fátima. Thousands of pilgrims and curious, journalists, photographers gathered at the site and experience an “unusual behavior” of the sun (“the sun danced”) which, as many believers were convinced, was a sign of the real presence of St Mary at the site.

1919 (April 4): Francisco de Jesus Marto, one of the three seers, died from the “Spanish” influenza pandemic. He was later canonized by Pope Francis in 2017.

1920: The new bishop of Leiria (later, Fátima-Leiria), Dom Jose Alves Correia da Silva (1872-1957), started to organize the site, buying the land, and planning to erect a new chapel and a hospital.

1920 (February 20): Jacinta de Jesus Marto also died from effects of the “Spanish” influenza pandemic. Jacinta was also canonized by Pope Francis in 2017.

1920 (May): A first small chapel (“capelinha”) was erected at the site of the apparitions. A year later, secularists destroyed it with a bomb, but the statue of the virgin remained unharmed (It had been removed before the explosion).

1921: The surviving seer, Lucia dos Santos was sent to a school in Porto; four years later she was admitted to a convent in Spain. She returned to Portugal in 1948 and lived in a convent in Coimbra until her death.

1922: Bishop Da Silva founded the monthly publication of the Voz da Fátima, (“Voice of Fatima”) which has been the official bulletin of the shrine of Our Lady of Fátima. By the mid-1930s, the publication reached 300,000 published copies.

1927: A mission dedicated to “Our Lady of Fátima” was consecrated in Ganda, Angola. This marked the beginning of the spreading of veneration throughout the Portuguese colonial empire.

1928: In Fátima, the construction of the Basilica and the monumental colonnades surrounding the pilgrimage site began and was finalized in 1954.

1929: Pope Pius XI blessed a statue of Our Lady of Fátima for the new chapel of the Portuguese College in Rome (founded in 1901), marking the beginning of the official support of the Vatican for Fátima.

1930: The official church report, ordered by Bishop Da Silva on the apparition was published. It confirmed that a “miracle” had happened in Fátima in 1917. However the report left open the question whether the Holy Virgin had actually appeared.

1933: Salazar’s Estado Novo, an authoritarian system that would be in place until 1974, was established. Salazar’s regime favored the Catholic Church in education and culture but limited its political influence.

1946: A Vatican legate, sent by Pope Pius XII, crowned the statue of Our Lady of Fatima, raising the importance of the pilgrimage site and the cult. In the same year, the first “pilgrimage statue” of Fátima was blessed by the Pope, in an attempt to bring the message of Fátima to all parts of the world.

1947: A large statue of Our Lady of Fátima was erected in Petropolis, Brazil, as an example of hundreds of chapels, churches, and shrines all over the Lusophone space as well as among other Catholic communities in Western Europe, Latin America, Australia and in other parts of the world.

1951: Jacinta and her brother Francisco were reburied together inside the Basilica of Our Lady of Fátima, after they had been buried earlier in the nearby cemetery. This raised the importance of the basilica.

1967: At the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the apparitions, Pope Paul VI celebrated mass at the pilgrimage site.

1982: Pope St John Paul II visited Fátima, thanking the Virgin for having saved his life after he had been shot on May 13, 1981. One of the bullets was later added to the crown of the statue of Our Lady of Fátima.

2000 (May 13): Pope St John Paul II celebrated mass at Fátima.

2010: Pope Benedict XVI visited Fátima.

2017 (May 13): Pope Francis celebrated the 100th anniversary of the first apparition in Fátima.

2022 (March 25): Pope Francis dedicated Ukraine and Russia to the Immaculate Heart of “Our Lady of Peace” and asked all bishops around the world to follow his example.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

“Fátima” stands for one of the most important contemporary Catholic pilgrimage sites. It began with an apparition of St Mary, the Mother of God, to three young shepherds from a nearby village in the course of Spring and Summer of 1917 in a field near the village of Fátima, Portugal. [Image at right] Since then, the pilgrimage site has been attracting millions of pilgrims and visitors while the cult of Our Lady of Fátima has spread to numerous countries around the world.

In the last year before the Covid Pandemic, more than 6,000,000 pilgrims visited the site, while the centenary in 2017, when Pope Francis visited the shrine, had seen a record of more than 9,500,000 visitors. This happened while the number of practicing Catholics in Portugal has been in steady decline since the Carnation Revolution of 1974. While about eighty percent of Portuguese still identify as Catholics, only a third of them are practicing, and the number of non-believers or of followers of other religions is slowly rising. In short, while Portugal is becoming a more secular and a more multi-religious society, the attraction to the shrine of Our Lady of Fátima has not declined. And, although this is mainly a Catholic pilgrimage site, it has also drawn interest and visitors from Muslim and Hindu backgrounds, partly because of the sheer coincidence that Fátima is also the name of the Prophet Mohamed’s daughter and partly due to the worldwide connections of the former Portuguese colonial empire.

All of this gives testimony to a transnational site that is at the same time global, national, and local. It is a ritualistic adoration of symbolic stories and objects in which millions of people participate. How do we explain the success of this site in a society where secularism and clericalism have often clashed? How did this national, at times even nationalist site, become a global site? What role did Portuguese colonialism and migration play in this? Finally, what does its history tell us about the complex relationship between a secularizing society and religion?

The question of the role of the Catholic church in the country had caused major political and social conflicts since the early nineteenth century when radical French secularist and revolutionary ideas had first arrived. This conflict had broken out again when a republican revolution brought down the monarchy in 1910. Some of the republican parties and politicians, which suffered from a lack of legitimacy because they were mostly based among the urban upper and middle classes in a mostly rural country, had adopted an aggressive anti-clerical program. It included restrictions of the freedom of religion, arrests of priests and bishops and similar actions that caused widespread anxiety among the rural, often illiterate masses of northern Portugal. The introduction of a 1911 law separating church and state, which represented the climax of a series of anti-clerical decrees, and laws which had targeted religious orders (suppression and confiscation of their property), religious marriage (legalization of divorce), religious education and even a ban on wearing the cassock in the street and the ringing of church bells, deepened this conflict. The conflict with urban, educated elites was further aggravated when the parliament, which represented a small elite, decided to support the Allies in the Great War in 1916. The Portuguese troops that were sent to the Western front were badly trained, which resulted in c. 20,000 casualties, including 8,000 dead. Many families around Fátima, including the families of the seers, were afraid that their sons would have to serve in the war. All this not only created anxiety and a sense of loss among a large part of the rural masses, but it also strengthened their resilience and hopes for a sign from heaven in support of their faith. Still, for most believers the apparition of the Holy Mother of God had mostly personal, social, or familial meanings.

When three young children (eight, ten, and eleven years-old) claimed that they had seen, and even spoken to, an apparition from heaven, between May and October 1917, many people seemed to have awaited such an event. The children grew up in very devout homes, embedded in deeply religious communities where the apparitions of Lourdes and other place were well known. When neighbors heard about the apparition, the news spread quickly, provoking very different reactions from families, villages, and local priests. These responses ranged from surprise and wonder to skepticism and rejection. However, from the second apparition in June on a continuously growing crowd of believers gathered at the site, first dozens, then hundreds, and finally, in September and October, thousands. The fact that Fátima at the time was difficult to reach, since there was no paved road or railway line, indicates the resolution of many to see the site personally.

Very soon, the children became interpreted by many in the community and in certain media outlets as “authentic” representatives of Portuguese rural society, as innocent, pure incarnations of local and national Catholic traditions. This belief was paradoxically strengthened and spread by the secularist press which scandalized the events. Additionally, the aggressive and often very awkward attempts of free masons and a republican, anti-clerical government and its local and regional executors to suppress the popular response also had the unintended consequence to make it even more popular. This was the case, particularly in the northern part of the country, which has the reputation of being a stronghold of Catholicism. During the last apparition on October 13, 1917, tens of thousands of pilgrims and curious people including numerous journalists arrived and many witnessed a solar spectacle (“the sun had danced”, as some said). This was seen by the believers as a sign of God, while non-believers tried to understand it as a mass hallucination of an over-excited crowd standing and waiting for hours for a miracle.

The leading Lisbon liberal-republican newspaper, O Século, founded in 1881 as a “voice of progress,” published a frontpage-article on October 15, 1917, two days after the event. Two weeks later, on October 29, 1917, the magazine published a longer article with numerous photos. This created a media event that made the occurrence known all over Portugal and beyond. One of the photos became iconic. [Image at right]

When the Great War ended in 1918, many believers thanked the Holy Virgin for bringing back peace and their sons safe from the front. The site further flourished during the 1920s, in another time of political turmoil and crisis in Portugal. During this time, the Catholic Church, in the person of Bishop Da Silva, took control of the site and tried also to manage the narratives related to it, which was not always successful. The death of the two younger visionaries, Francisco (1919) and Jacinta (1920) by the “Spanish” flu pandemic, left the oldest of the three, Lucia dos Santos, as the only witness. In 1935, Bishop da Silva prompted Sister Lucia, who had been in a convent in Spain since 1921, to write down her memories. In 1941, she would then author her third account, in which she would also describe the first two “secrets” that the Holy Mother of God had revealed to her. Two years later, she revealed the “third secret” of Fátima and sent it in a sealed envelope to Bishop da Silva, not to be opened until 1960. The text of this third secret was published by Pope John Paul II in the year 2000. (Vatican. Congregation of the Faith: The Message of Fátima 2000) For some, the “secrets” written down by Sister Lucia had the quality of apocalyptic prophesies and a number of conspiracy theories evolved around them.

The success of Our Lady of Fátima lies in its openness to many different interpretations, which can be understood by numerous groups and individuals as directed towards them. As described above, the political, social, and cultural crisis of Portugal in the first third of the twentieth century contributed strongly to the establishment of Fátima as a national symbol. This standing was further strengthened by the authoritarian regime of Salazar in the next decades. During that regime, the Catholic Church gained prominence in public education and culture. In this context, Our Lady of Fátima, which was already extremely popular, played a major role. More and more churches, sanctuaries, and missions in the Portuguese colonies, from Macao in China (1929) to places in Angola, Mozambique and Guinea (Guinea-Bissao) in Africa, were dedicated to Fátima.

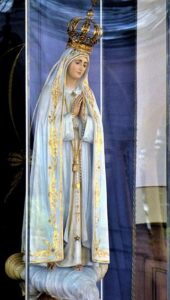

It was also essential that the popes, beginning with Pius XI (1922-1939), supported Fátima. In 1929, Pope Ratti, blessed a statue of the Virgin of Fátima for the new chapel of the Portuguese College in Rome. For his successor, Pope Pius XII (1939-1958), Fátima had an even greater significance. During World War II, he consecrated the world to the Immaculate Heart of St Mary (October 31, 1942). In 1946, Pius XII sent a legate to Fátima to crown the statue of Our Lady of Fátima. [Image at right]

In the same year, 1946, a “pilgrimage statue” of Our Lady of Fátima was blessed which was supposed to bring the message to different parts of the world; soon, a dozen such statues would be sent out to numerous places around the globe. Often, Fátima veneration followed the path of millions of Portuguese emigrants, to Brazil, North America, Australia, and later to France, West Germany, Switzerland, and Luxembourg. However, Fátima has also been adopted by non-Portuguese Catholic communities in many countries, especially in Spain and Poland.

Since the 1980s, Portugal has become a country of immigration, not only from former colonies (including Brazil) but also from Ukraine and other places. For many of these groups, Our Lady of Fátima has become a bridge to connect to the new home in Portugal. A good example for this is a group that is related to the Gujarati Hindu (Lourenço and Cachado 2022) Here, statues of Our Lady of Fátima have been integrated into Hindu practices. In the last decades, the pilgrimage site and the cult as such, have become important vehicles to promote tourism to Portugal.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The apparitions or “visions” (the term used by the Catholic Church) to the three children Lucia, Francisco, and Jacinta, began in 1916, when they saw an angel. On May 13, 1917, when they were out herding the sheep they saw a lightning and started to walk back, then “there was another flash of lightning, and, two steps ahead, we saw on top of a holm oak tree, that would have a meter of height, approximately, a Lady,” according to Sister Lucia (Cristino 2011:2). Two weeks later, Lucia described the apparition to the local priest as a white lady dressed in white with a golden skirt and a golden necklace who stretched out her arms and said that they should not be afraid. Lucia spoke to the apparition who asked them to pray the rosary each day to end the war, and to come back on the thirteenth day of the following six months.

During the second apparition, according to Lucia’s memories, written in 1941, St Mary told her that they would all go to heaven but that Jacinta and Francisco would be taken soon. (However, it is worth noting that Lucia wrote this account in 1927, after the two younger children had been dead for several years) (Cristino 2012:3). At this occasion, a penetrating light also radiated from the Lady and shone on the three children; they understood that this was the Immaculate Heart of Our Lady.

The most important apparition was the third, on the July 13, 1917 because on that day, the Lady (she would only reveal that she was the Mother of God on October 13) would reveal the “three secrets” to Lucia. She would write those down in 1941.

The first secret was an apocalyptic vision of hell with fires and demons and suffering human souls, a vision which the children said scared them. The second secret the Lady delivered referred to Russia, which she warned had abandoned the Mother of God and which would spread its errors all over the world. The Lady asked that Russia should be dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary so that the world would be at peace again. This second secret was soon enthusiastically adopted by many anticommunist groups, especially during the Cold War, since they regarded it as a heavenly message directed against the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and its consequences.

The third secret was only published in the year 2000 by Pope John Paul II. Lucia had written it down in 1944 and had handed it over to Bishop Da Silva in a sealed envelope with the instruction that it should not be opened until the year 1960. Popes John XXIII and Paul VI decided not to open the envelope. In this last vision or third secret, Lucia described a mountain, fires in the sky, ruins, and a number of men dressed in white. Lucia identified the men as priests and bishops, who were trying to hide. Soldiers shot at them. Many died. Under a cross, two angels appeared who collected the blood of the martyrs to “water the souls that approached God” (Cristino 2013:7). One of the men who was killed was later interpreted as a pope. Later, many believed that this vision referred to the assassination attempt against John Paul II, who was shot on May 13, 1981. However, the “secrets” belong to the most controversial elements of Our Lady of Fátima supporters; therefore, the Vatican tries to contain possible implications and interpretations. (See, Issues/Challenges)

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Numerous rituals have been established in relation to the sanctuary of Our Lady of Fátima at the site in Portugal. There also are many rituals, like annual processions of statues, in many parts of the world where other shrines dedicated can be found.

The most important and least contested ritual is the praying of the rosary. Not only did the three visionaries pray the rosary before the apparitions, but Our Lady of Fátima has also long been called “Our Lady of the Rosary of Fátima.” Currently, frequent prayers in various languages are offered by priests at the Sanctuary, and they are also transmitted by radio and the internet. Additionally, there are regular masses in different languages and in the various churches on site.

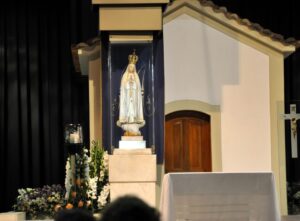

Pilgrims and pilgrim groups have usually begun their visit at the capelinha (the “little chapel” or “Chapel of the Apparitions,”) erected in 1919. The original statue of Our Lady of Fátima stands here on the site where the apparitions took place. [Image at right] Other important places pilgrims visit are the grave sites of the visionaries in the sanctuary as well as the nearby path between the town and the village (Via Sacra, with fourteen stations of the cross), where the humble houses can be visited in which the three shepherds lived at the time. Walking this path, pilgrims can imagine how the three children walked from their homes to the site of the apparition, although the environment has drastically changed that period as a result of urbanization.

Another very important and popular ritual is the candlelight processions (between May and October) at the shrine that often brings thousands of participants. All of these the rituals now have also been packaged and included into tourist visits to Portugal.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Since 1920, the Sanctuary of the Rosary of Our Lady of Fátima has become a complex of various religious buildings around the main Basilica and the small chapel (originally built in 1919, later reconstructed). Around the sanctuary, a number of hospitals, pilgrimage hotels, restaurants, and other services were constructed, particularly since the 1950s, and again, since the 2000s. From an open field in 1917, Fátima has grown into a city with more than 13,000 inhabitants (city status since 1997). The shrine is administered by a rector, a priest, under the leadership of the Bishop of Leiria-Fátima.

After the first apparitions to the three children, various people (family members, neighbors, the parish priest, and people from the surrounding villages) became curious and asked questions or visited the site. During the summer months, hundreds, soon thousands of pilgrims, or curious people and a few journalists and photographers gathered near the site on the 13th of the month. After the apparitions ended with the “miracle of the sun” on September 13, 1917, a first, temporary wooden structure was built by local practitioners. After the deaths and the reburial of the three children, in 1920, the new bishop of Leiria (the diocese was re-organized in 1918), da Silva, took over the site. He bought the land and ordered the erection of a new, larger chapel. Since that time, the church has taken full control over the organization of the shrine.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Many books, articles and videos have been published on Fátima since 1919 in order to interpret the 1917 events. Since the beginning, as Helena Vilaça has written, there has been strong tensions between popular ideas and the official position of the Catholic Church (Vilaça 2018:68). The official theological interpretation of the apparitions by the Vatican defines them as “private revelations,” in contrast to the “public revelation,” which is represented by the Bible. In the 2000 document “The Message of Fátima,” then Cardinal Ratzinger, head of the Congregation of Faith before being elected pope, explained that such “miracles” as the apparitions in Fátima “help us to understand the signs of the times and to respond to them rightly in faith” (Vatican. Congregation of the Faith: The Message of Fátima 2000). But Ratzinger also emphasized that the “secrets” (he uses the quotation marks in order to distance himself from the term!), as the Catholic Church is interpreting them, would disappoint many who are looking for “prophecies” about the world. Most of all, the church cannot accept any ideas or interpretations that would contradict or add to its teachings. He tried to be very clear:

The purpose of the vision is not to show a film of an irrevocably fixed future. Its meaning is exactly the opposite: it is meant to mobilize the forces of change in the right direction. Therefore, we must totally discount fatalistic explanations of the “secret”, such as, for example, the claim that the would-be assassin of 13 May 1981 was merely an instrument of the divine plan guided by Providence and could not therefore have acted freely, or other similar ideas in circulation. Rather, the vision speaks of dangers and how we might be saved from them. (Vatican. Congregation of the Faith: The Message of Fátima 2000).

Ratzinger’s clear statement from 2000 has not, of course, stopped the circulation of all kinds of ideas related to Fátima and the “secrets.” There have even speculations about a “fourth secret” which was “hidden” by the Vatican. Authors have sold hundreds of thousands of expositions of such “theories” (e.g., Socci:2009).

IMAGES

Image #1: A statue of St Mary, the Mother of God with the three children visionaries.

Image #2: A 1917 photo of the three child visionaries that became iconic.

Image #3: The original statue of Our Lady of Fátima (1919/1920).

Image #4: the capelinha (the “little chapel” or “Chapel of the Apparitions,”) erected in 1919.

Image #5: The statue of Our Lady of Fátima wearing a crown placed by a legate of Pope Pius XII in 1946.

REFERENCES

Cristino, Luciano. 2013. A terceira aparição de Nossa Senhora na Cova da Iria em 13 de julho de 1917. Accessed from https://www.fatima.pt/pt/documentacao/e006-a-terceira-aparicao-de-nossa-senhora-na-cova-da-iria on 10 July 2023.

Cristino, Luciano. 2012. A segunda aparição de Nossa Senhora na Cova da Iria (13.06.1917). Accessed from https://www.fatima.pt/pt/documentacao/e008-a-segunda-aparicao-de-nossa-senhora-na-cova-da-iria on 10 July 2023.

Cristino, Luciano. 2011. A primeira aparição de Nossa Senhora, a 13 de maio de 1917. Estudos. E011. Accessed from https://www.fatima.pt/pt/documentacao/e011-a-primeira-aparicao-de-nossa-senhora-a-13-de-maio-de-1917 on 10 July 2023.

Lourenço, Ines and Rita Cachado. 2022. “Hindu Diaspora in Portugal: The Case of Our Lady of Fatima Devotion.” Pp. 603-09 in Hinduism and Tribal Religions. Encyclopedia of Indian Religions, edited by in J.D. Long, R.D. Sherma, P. Jain, and M. Khanna. Dordrecht: Springer.

Socci, Antonio. 2009. The Fourth Secret of Fátima. Loreto Publications.

Vatican. Congregation of the Faith: The Message of Fátima. 2000. Accessed from https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_20000626_message-fatima_en.html on 10 July 2023.

Vilaça, Helena. 2018. “From a Place of Popular Religiosity to a Transnational Space of Multiple Meanings and Religious Interactions.” Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion 9:68-82.

Von Klimo, Arpad. 2022. “The Cult of Our Lady of Fátima—Modern Catholic Devotion in an Age of Nationalism, Colonialism, and Migration.” Religions. Accessed from https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/13/11/1028 on 10 July 2023.

Publication Date:

13 July 2023.