BAPS TIMELINE

1781 (April 13): Swaminarayan was born as Ghanshyam in Chhapaiya, Uttar Pradesh, India.

1786 (March 31): Ghanshyam began studying Sanskrit at the age of five.

1792: Ghanshyam left home to begin a seven-year pilgrimage across India and came to be known as Neelkanth Varni.

1794 (October 24): Neelkanth mastered ashtanga yoga.

1799 (August): Neelkanth arrived at the hermitage of Ramanand Swami.

1800 (October): Ramanand Swami initiated Neelkanth into the sampradaya and named him Sahajanand Swami.

1801 (November): Ramanand Swami appointed Sahajanand Swami as the leader of the Sampradaya.

1801 (December): Ramanand Swami passed away.

1801 (December 31): Sahajanand Swami instructed his followers to chant the “Swaminarayan” mantra, marking the beginning of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya.

1826: Swaminarayan established two dioceses, Ahmedabad and Vartal and appointed acharyas (the heads of a sampradaya) as administrators to manage the mandirs (temples) in their regions.

1830 (Feburary 28): Sir John Malcolm, governor of the Bombay Presidency, met with Swaminarayan.

1830 (June 1): Swaminarayan passed away.

1830 (June 2): Gunatitanand Swami took over the spiritual leadership of the Sampradaya.

1907: Shastri Yagnapurushdas (1865-1951) split from Vartal and Ahmedabad due to theological differences and established the Bochasanwasi Shri Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha (BAPS).

1947: BAPS became a registered and certified trust.

1950: Pramukh Swami Maharaj became president of BAPS.

2016 (August 13): Administrative and spiritual head of BAPS, Pramukh Swami Maharaj passed away.

2016 (August 13): Mahant Swami became the successor to Pramukh Swami Maharaj as administrative and spiritual head of BAPS.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Swaminarayan is the founder of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya, a Hindu bhakti (devotional) community (Brahmbhatt 2014:99) (Image at right). He was born on April 3, 1781 in Chhapaiya, in Uttar Pradesh in India and was named Ghanshyam Pande (I. Patel 2022:1582). His parents were Hariprasad Pande and Premvati, and they belonged to the Brahmin caste of Sarvariya (Williams 2018:14). Ghanshyam studied Hindu texts under the guidance of his father, and after the death of his parents, he left home at the age of eleven to set off on a pilgrimage throughout India (I. Patel 2022:1582). He renounced the world by taking up the practice of ascetic wandering students (brahmachari) (Williams 2018:14), learned the eight-fold yoga system, and performed austerities (I. Patel 2022:1582). He was seeking a religious order that aligned with his theological perspective, and at this time he adopted the name Nilkanth Varni (Mamtora 2016:831).

In August 1799, he arrived at the hermitage of Ramanand Swami (1739-1801). In October 1800, Ramanand Swami initiated Nilkanth Varni into the Sampradaya (monastic order) and named him Sahajanand Swami (Mamtora 2016:831) and Narayan Muni (I. Patel 2022:1582). In November 1801, Ramanand Swami appointed Sahajanand Swami as the leader of the Sampradaya; Ramanand Swami passed away one month later. Thirteen days after the passing of Ramanand Swami, Sahajanand Swami instructed his followers to chant the “Swaminarayan” mantra, and this is considered to be the beginning of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya. Sahajanand Swami came to be known as Swaminarayan due to the prominence of this mantra.

Over the next twenty-nine years, Swaminarayan initiated an estimated 2,000 (Raymond Brady Williams 2018:23) to 3,000 (Brahmbhatt 2014:100) sadhus (holy men) who spread his teachings throughout Gujarat (I. Patel 2022:1582). British sources estimated that by the 1820s, Swaminarayan had at least 100,000 followers, while some in the community suggest that the following had grown to 1,800,000. He allowed women to practice ascetic life, and they lived in separate spaces in the temples (Williams 2018:. 22–23).

The development of Swaminarayan’s movement took place within the context of great social change in Gujarat. By 1820, Gujarat had come under the control of the British. In the first two decades of the nineteenth century, the Rajput and Kathi chiefs had conducted many raids, resulting in a breakdown of law and order. There was a lack of peace and security because of friction between various chieftains and rulers. Civic order broke down due to drought, famine, epidemic, an earthquake, and poverty in Gujarat, and due to scarcity, armed bands engaged in killing and looting. It was within this context that colonial rule over parts of Gujarat was justified, as well as religious and social reforms that were supported by Swaminarayan. The desire to restore civil order was a shared goal for British and Swaminarayan leaders (Williams 2018:6–9). Sir John Malcolm, an official of the British East India Company who had became governor of the Bombay Presidency, met with Swaminarayan on Feburary 28, 1830 (Williams:2018:4). By that time, Swaminarayan was known as a religious reformer who raught that sati and female infanticide were not a legitimate part of orthodox Hinduism (Williams 2018:12).

Swaminarayan’s followers point out that his preaching and teachings had an influence on the people of Gujarat in leading morally upright and peaceful lives while the region was in the throes of civil unrest (Williams 2018:13), and Swaminarayan leaders worked with British leaders to discuss how to deal with civic and religious issues (Williams 2018:22). Swaminarayan spread a message of social and religious reform, and a major element of reform was the strict discipline required of his ascetic disciples. The ascetics took part in works for social welfare to restore order and security in the region. They engaged in manual work including digging and repairing wells, building and repairing roads, and building temples and homes. They opened kitchens to feed people during times of famine and engaged in relief efforts in areas affected by diaster. The ascetics were also trained as teachers and preachers to spread the teachings of Swaminarayan in the villages, and this led to the rapid growth of the movement (Williams 2018:26).

After meeting with Swaminarayan, Malcolm met with the leaders of the Jarijah caste of Rajputs and tried to persuade them to give up the practice of female infanticide. He believed that recovering from political instability and achieving social and moral reform would be accomplished through the leadership of enlightened leaders. At that time, Swaminarayan was one of the most influential Indian leaders in Gujarat, and for this reason, Malcolm arranged to meet with him (Williams 2018:13). They both abhorred the practices of infanticide and the immolation of widows, and Swaminarayan preached that infanticide is forbidden because it is sinful. He raised money to pay for the marriage expenses of daughters if they would be spared. Infanticide was finally banned by the government in 1870. Swaminarayan also preached against widow suicide, and he made provision for women who wanted to lead a life of devotion to live an ascetic life, so that they could have a position in society as widows. Malcolm and other British officials encouraged and supported Swaminarayan in his reform efforts which were the focus of his movement in his final years. His movement helped to bind the territory together after a period of turmoil, and his establishment of holy places and temples as places of pilgrimage has become a significant part of Gujarati cultural identity (Williams 2018:31–33).

Swaminarayan passed away on June 1, 1830 (I. Patel 2022:1582). The next day, Gunatitanand Swami took over the spiritual leadership of the Sampradaya and became Swaminarayan’s successor (Raymond Brady Williams 2018:61, 66; BAPS 2024b; Sadhu Vivekjivandas 2024). As is so often the case in religious movements, the succession put in place after the founder’s death had ramifications for how the Sampradaya would continue in the future (See, Organization/Leadership).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

At the core of Swaminarayan’s doctrine are five entities that informed his teachings on devotion, practice, and liberation: jiva (the souls of ordinary beings); ishvara (higher order beings with cosmic functions); maya (an instrument of Parabrahman in the formation of the material world); Brahman (the supreme God); and Parabrahman (the supreme God). In a departure from earlier thinkers, Swaminarayan discusses two Brahmans in his teachings, Aksarabrahman and Parabrahman (Patel 2022:1583). Akṣarabrahman is the abode of Parabrahman. In its human manifestation, Akṣara helps spiritual practitioners realize their true form to be an atman and become like Brahman. Parabrahman, also called Puruṣottama and Paramatma, is the supreme God and is superior to Akṣarabrahman (Sadhu Bhadreshdas 2016; Swami Paramtattvadas 2017). The supreme person is Purushottam and akshar is the abode of Purushottam and has an impersonal form. It is the cosmic principle and mediates the activities of the supreme person (Williams 2018:86, 91)

In formulating his doctrines, Swaminarayan considered eight texts as authoritative: the Vedas; Vedantasutras; Bhagavatapuraṇa; Bhagavadgita, Vīṣṇusahasranama, and Viduraniti from the Mahabharata; Vasudev Mahatmya from the Skandapurana; and Yajnavalkyasmrti (I. Patel 2022:1582). Two texts are particularly important for his followers. First, the Vachanamrut, which is a collection of Swaminarayan’s sermons, and second, the Shikshapatri, a book of instructions on devotional and moral conduct (Mamtora 2016:831), consisting of 212 Sanskrit verses attributed to Swaminarayan (Brahmbhatt 2014:101).

An important teaching within the Swaminarayan movement is that the highest manifestation of God takes a human form in God’s eternal abode, and in line with Vaishnava understanding, God descends in a human form to earth to help humankind (Williams 2018:78–79). These manifestations are called avatars, which means one who descends, and Swaminarayan instructed his followers to worship only avatars in human form, with worship being directed primarily to Krishna and Rama (Williams 2018:80).

It is widely believed by the followers of Swaminarayan that he is an incarnation of Krishna (Williams 2018:82) and others believe he is a manifestation of Purushottam (Williams 2018:85). However, in Swaminarayan’s lifetime, opinion on this was split, with some followers resisting this idea (Williams 2018:83). Followers worship Sahajanand as Swaminarayan, a manifestation of God (Raymond Brady Williams 2018:77), and aim to realize that the God who manifests on earth in the human form of Swaminarayan is the topmost supreme being and the cause of all avatars (Raymond Brady Williams 2018:88). Swaminarayan’s purpose in appearing on earth is said to be of for the redemption of souls and for establishing moral and social order, as well as fulfilling his devotees’ desire to have intimate and direct contact with God (Williams, 2018:98). Followers aim to see the divine form of God and in so doing, overcome attachment to the world from the cycle of rebirth (samsara) by Swaminarayan’s grace. The belief that contact with the manifestation of akshar on earth is necessary for reaching Purushottam is a defining aspect of BAPS theology (Williams 2018 99–100).

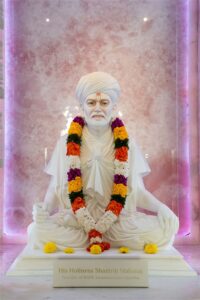

The major split in the movement came about due to differences in the teaching about the personal form of akshar. Swami Yagnapurushdas, also known as Shastriji Maharaj (Image at right), identified the personal form of akshar with Swami Gunatitanand (1785–1867) who was a close companion and disciple of Swaminarayan. Swami Yagnapurushdas argued that Purushottam is always accompanied by his perfect devotee and that God continues to manifest himself to his devotees in human form through his perfect devotee. The majority of the sadhus in Vadtal rejected this teaching as heresy and refused to worship what was, in their opinion, a human being. Swami Yagnapurushdas broke away from Vadtal and formed the Bochasanwansi Shri Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha (BAPS). Followers of Ahmedabad and Vadtal dioceses teach that the name Swaminarayan represents one entity, Purushottam. BAPS members hold that the name represents two entities; “Swami” stands for akshar represented by Gunatitanand and his successors, and “Narayan” stands for Purushottam, or Sahajanand. BAPS members align themselves with both by chanting the Swaminarayan mantra (Williams 2018:92–93)

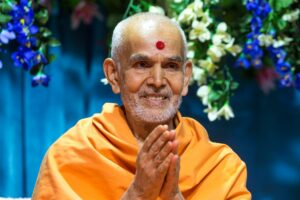

As a result of this different interpretation of akshar, BAPS subscribes to the conception of an unbroken line of perfect devotees who appeared as manifestations of akshar. These manifestations are the leaders and spiritual gurus of BAPS (the guru parampara, or line of teachers) and this lineage  can be traced back to Gunatitanand, and ultimately to Swaminarayan. The current representative is Swami Keshavjivandas, more popularly known as Mahant Swami (Image at right). He is the spiritual guru for all members, in addition to being the administrative head of BAPS. As well as being a channel for divine grace, the guru is believed to be absolutely divine (Williams 2018:93–95).

can be traced back to Gunatitanand, and ultimately to Swaminarayan. The current representative is Swami Keshavjivandas, more popularly known as Mahant Swami (Image at right). He is the spiritual guru for all members, in addition to being the administrative head of BAPS. As well as being a channel for divine grace, the guru is believed to be absolutely divine (Williams 2018:93–95).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

According to Swaminarayan, one who practices the higher form of devotion worships Purushottam, and realizes the self is like akshar, who is the abode of Purushottam Narayana. Such a devotee is called an ekantik bhakta, who has perfected ekantik dharma, which is the constant practice of bhakti (devotion) towards God through jnana (knowledge), vairagya (detachment from anything other than God) and dharma (right behaviour in service to God) (Patel 2022:1583).

To cultivate ekantik dharma, Swaminarayan encouraged his followers to engage in temple worship, participation in festivals, rituals, didactic addresses, following devotional behavior, and thinking about model devotees of God. He emphasised the execution of seva (service) as a form of bhakti, stating that “a devotee should not wish for anything except the service of God” (Gadhada 1-43 cited in Brahmbhatt, 2014:107). Seva also extends to serving the guru (Gadhada 11-25 cited in Brahmbhatt 2014:108) and devotees of God, and is also broadened to include wider society and humanity (Brahmbhatt 2014:108). Seva is executed through activities and financial support, and in Swaminarayan’s lifetime it included engaging in social projects such as digging wells, running welfare centers and literacy programs for women, and preaching against female infanticide and sati (Patel 2022:1583).

Some of Swaminarayan’s followers were sadhus (holy men who engage in devotional and ascetic practice) who took vows that the laity also took, that is, to refrain from: stealing; intoxication; eating meat; adultery; and impurities of body and mind. The sadhus took five additional vows: celibacy; detachment from the body; humility; to not covet wealth; and detachment from food. These vows remain as important pillars of practice within BAPS today. Swaminarayan also instructed his followers to avoid interacting with the opposite gender at the temple and during religious events, which resulted in separate congregational activities for males and females, a practice that also persists to this day (Patel 2022:1584).

Members of the Ahmedabad and Vadtal dioceses believe that Swaminarayan is present in images installed by the acharya, and in the sacred scriptures authored by him. BAPS believes that Swaminarayan is present in the form of the guru and in images and sacred scriptures. Mahant Swami performs morning worship before a small image of Swaminarayan called the thakorji. This ritual is observed by devotees who are personally present and those who observe the rituals via the Internet (Williams 2018: 100).

Images in the central shrines of Swaminarayan temples are statues of the human form of God, and daily rituals in the temples act out the events of the daily life of God in human form and encourage meditation on God. Most temples also house shrines to gods in nonhuman form, including Hanuman and Ganapati, but they are in subsidiary shrines at the entrance to the temple. In line with the prominent position of Swaminarayan over Krishna, ritual worship is focussed on him and Krishna takes a subordinate position (Williams 2018:103). As such, the image of Swaminarayan is in the central  position in the main shrine of all BAPS temples and the images of Krishna and Radha are in a side shrine. In BAPS temples, the image of Gunatitanand, a manifestation of God’s ideal devotee, sits to the left of Swaminarayan (Williams 2018:105) (Image 4 at right).

position in the main shrine of all BAPS temples and the images of Krishna and Radha are in a side shrine. In BAPS temples, the image of Gunatitanand, a manifestation of God’s ideal devotee, sits to the left of Swaminarayan (Williams 2018:105) (Image 4 at right).

Members of BAPS and its charitable organizations engage in seva (service to society) by carrying out social service activities in the following areas: medical; educational; disaster relief; welfare; environmental; community; and rural development services (BAPS Charities n.d.). The Akshar Purushottam Public Charitable Trust was established in India in the 1950s, and subsequently, BAPS Charities, an international nonprofit organization was formed, and is engaged in over 160 humanitarian activities (Brahmbhatt 2014:99). Anand (2004:53) proposes that BAPS “focuses on philanthropy that arises from a religious motivation for the greater good of the society” and Brahmbhatt (2014:118) argues that while the social service of the organization’s members is religiously motivated and seen as an act of devotion, the service is not tied to a religious or proselytizing mission.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Swaminarayan institutionalized the Swaminarayan Sampradaya by constructing six mandirs (temples) in Gujarat (Mamtora 2016:831). Within the mandirs he installed images of deities and their ideal devotees, in accordance with his view that God should be worshipped alongside God’s ideal devotee (Patel 2022:1582). He installed his image at the Sri Laksminarayan mandir in Vartal, Gujarat (Mamtora 2016:831). Swaminarayan established two dioceses (Ahmedabad and Vartal) and appointed acharyas as administrators to manage the mandirs in their regions in 1826 (Mamtora 2016, 831). He appointed his two nephews to the role of administrators, which later established a hereditary line of succession. He identified Gunatitanand Swami as his eternal, ideal devotee as someone from whom his followers could take spiritual guidance, and in doing so, he established a line of gurus (parampara) (I. Patel 2022:1582).

After Swaminarayan’s death, new branches of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya were established. In 1907 Shastri Yagnapurushdas (1865-1951) split from Vartal and Ahmedabad due to theological differences about the nature of akshar that were discussed in the section on doctrines and beliefs. The breakaway group established the Bochasanwasi Shri Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha (BAPS) (Mamtora 2016:831).

BAPS had its first sustained migration outside of Gujarat and India, as Indians, and specifically Gujaratis migrated to East Africa as labor opportunities opened up due to British colonization (Williams 2001). During the policy of Africanisation in East Africa in the 1960s and  1970s, many Gujaratis left, with some members of the Swaminarayan movement going to Gujarat. The majority migrated to the United Kingdom, and they began to build temples there from 1970. A new temple was opened in Neasden in London in 1995, and it is the most important of BAPS’ overseas temples (Dwyer 2004:193). (Image 5 at right).

1970s, many Gujaratis left, with some members of the Swaminarayan movement going to Gujarat. The majority migrated to the United Kingdom, and they began to build temples there from 1970. A new temple was opened in Neasden in London in 1995, and it is the most important of BAPS’ overseas temples (Dwyer 2004:193). (Image 5 at right).

BAPS became a registered and certified trust in 1947 (Sadhu Amrutvijaydas 2007). The trust was managed by an administrative committee led by a president, and from 1950 the president was Pramukh Swami Maharaj (Williams 2001). Brahmbhatt (2014) notes that there was a distinction between administrative and spiritual leadership, with Pramukh Swami Maharaj taking the role of administrative president under two different spiritual leaders, before he became both the spiritual and administrative leader. On August 13, 2016, Pramukh Swami Maharaj passed away (Marketwired 2016). His Holiness Mahant Swami was named as his successor and spiritual head of BAPS (Eastern Eye 2016).

A rationalized system of organization and hierarchical management (Kim 2008) has developed within BAPS in the United States, Britain, and other areas to manage the activities of 55,000 volunteers worldwide (BAPS 2024b). Rather than one overall structure in BAPS administrative organization, several trusts have been established to support activities, including social service activities globally (Brahmbhatt 2014:104). BAPS Charities is a global charity established in 2000 to oversee humanitarian activities and is registered in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and New Zealand. Working in five key areas, BAPS Charities, oversees selfless service to society through health awareness, educational services, humanitarian relief, environmental protection and preservation, and community empowerment (BAPS Charities n.d.).

There are now an estimated 30,000 members of BAPS in the United Kingdom, 40,000 members in the United States, and one million members worldwide (Kim 2009). BAPS has mandirs globally, in India, Europe, North America, Asia Pacific, the Middle East, and Africa. Its International Headquarters are located in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. The global network consists of more than 1300 mandirs and 5025 centers (BAPS 2024a).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

A number of schisms have occurred within the Swaminarayan movement. The most significant schism came about due to theological differences discussed in the doctrines and beliefs section and resulted in the founding of the Bochasanwasi Shri Akshar Purushottam Sanstha (BAPS), which broke away from the original movement. This involved a major doctrinal split and institutional division within the movement (Raymond Brady Williams 2018, 60). The Swaminarayan Gadi was founded when Muktajeevandas Swami left the Ahmedabad temple in the 1940s. He rejected the householder acharyas as the legitimate successors of Swaminarayan and established his own institution. He claimed that the authentic lineage is from Gopalanand Swami, who was a prominent sadhu during Swaminarayan’s time (Williams 2018:57–58).

As a result, there are three major divisions of the Swaminarayan movement: the original Ahmedabad and Vadtal dioceses led by the acharyas of Ahmedabad and Vadtal; BAPS; and the Swaminarayan Gadi (Williams 2018:60). The two largest and most important are the original Ahmedabad and Vadtal dioceses, which follow the acharyas of Vadtal and Ahmedabad, and BAPS, which gives allegiance to Mahant Swami as the current akshar and spiritual guru in succession from Gunatitanand Swami (Williams 2018:73).

Aside from this major schism, several other schisms have beset the Swaminarayan movement within all three major divisions. Regarding BAPS specifically, the Yogi Divine Society separated from BAPS in 1966 over a dispute about leadership and initiation of women. Dadubhai Patel claimed authorization from his guru, Yogiji Maharaj, to invite young women to accept initiation as BAPS ascetics and to raise funds for a women’s ashram in India. Trustees in India expelled Dadubhai and his brother, Babubhai, from BAPS shortly thereafter. Dadubhai subsequently established a mission at Vidyanagar, where some of the young women from East Africa resided as ascetics. A few sadhus then established a center at Sokhda near Baroda. They accept Yogiji Maharaj as their guru, but they rejected the authority of his BAPS successor, Pramukh Swami (Williams 2018:72). BAPS still does but not permit the initiation of female ascetics; however, some elderly respected women live according to strict ascetic vows. On the other hand, female ascetics (samkhya yoginis) form part of the Ahmedabad and Vadtal dioceses and they receive initiation from the wives of the acharyas (Williams 2018:126–27).

A number of controversies have plagued the organization in the last few years. In the middle of political turmoil and intercommunal religious conflict, a terror attack on the Akshardham Swaminarayan complex in Gandhinagar, Gujarat took place on September 24, 2002. Two Muslim men entered the complex, carrying assault rifles and grenades, killing thirty-three people and injuring more than seventy7. The Indian government brought in the anti-terrorist Black Cat commandos and the siege ended early the next morning when the commandos killed the two men. The deceased included the two assailants, three commandos, four Swaminarayan volunteers, and one sadhu on the staff at the complex (Williams 2004:131).

A dispute arose in the construction of a BAPS temple at Chino Hills in California in 2003. It initially faced intense opposition from the local community whose residents claimed that traditional architectural elements of the temple would disrupt the city’s natural beauty. Some residents argued that the existence of the temple would usher in unwelcome changes in the city’s religious, cultural, and demographic makeup. The dispute ran for twelve years, but eventually, local community members who were initially opposed to the construction of the temple offered overwhelming support (A. Patel 2018).

In 2021, the New York Times reported allegations that forced labor was being used to build the Akshardham Mahamandir in Robinsville, New Jersey. Federal law enforcement agents entered the construction site of a BAPS temple in New Jersey after workers filed a lawsuit against the organization, accusing it of luring them from India, confining them to the temple grounds, forbidding them to talk to visitors, confiscating their passports and paying them the equivalent of about $1 an hour to perform hard labor. The workers entered the country on religious workers visas and the majority of them were said to be from Dalit backgrounds (Correal 2021). A spokesman for the temple said the workers came to the United States as volunteers, not as employees because volunteerism is a core part of their religious tradition, and he advised that temple officials were cooperating with the investigation. The temple opened in 2023, and a federal criminal investigation and a wage claim lawsuit has been ongoing (Bailey 2023).

In 2023, the BAPS temple in Sydney was vandalised, along with other Hindu temples prior to an official visit by Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi. “Declare Modi terrorist” was spraypainted on the temple in September 2024, motivated by campaign by activists who want to form a break-away state (Khalistan) for Sikhs in India (The Sydney Morning Herald 2023).

The Swaminarayan movement has undergone significant changes since its founding in the early nineteenth century due to a number of issues and challenges. The most significant of these changes has been the division of the movement into three major divisions due to theological differences and issues around succession and leadership. Of these three divisions, BAPS has become the most prolific. It has become one of the fastest-growing religious groups in Gujarat, and in India, and is the most prominent Hindu organization in Britain and North America (Williams 2018:60).

IMAGES

Image #1: Swaminarayan. Credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki.

File: Swaminarayan,_founder_of_the_Swaminarayan_Sampradaya.png. Copyright held by BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha (web: www.baps.org, email: info@baps.org);, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image #2: Shastriji Maharaj. Credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BAPS_Abudhabi_15.jpg

BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image #3: Mahant Swami. Credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mahant_Swami_Maharaj.jpg

Copyright held by BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha (web: www.baps.org, email: info@baps.org), CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.x

Image#4: Swaminarayan and Gunatitanand Swami (collectively known as Akshar-Purushottam Maharaj).

Credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BAPS_Abudhabi_17.jpg

BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image #5: BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir, London. Credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File: BAPS_Shri_Swaminarayan_Mandir,_London_-_geograph.org.uk_-_4743308.jpg

Shri Swaminarayan Mandir, London by Robin Webster, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

REFERENCES

Anand, Priya. 2004. “Hindu Diaspora and Religious Philanthropy in the United States.” In Toronto: Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society, New York. Accessed from https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.istr.org/resource/resmgr/working_papers_toronto/anand.priya.pdf on 25 September 2024.

Bailey, Sarah Pulliam. 2023. “A $96 Million Hindu Temple Opens Amid Accusations of Forced Labor.” New York Times, October 21. Accessed from https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/21/nyregion/nj-hindu-temple.html on 25 September 2024.

BAPS. 2024a. “BAPS Global Network.” BAPS.Org, 2024. Accessed from https://www.baps.org/Global-Network.aspx on 25 September 2024.

BAPS. 2024b. “History and Milestones.” BAPS, 2024. Accessed from https://www.baps.org/About-BAPS/WhoWeAre/HistoryandMilestones.aspx on 25 September 2024.

BAPS Charities. n.d. “About Us.” BAPS Charities. Accessed from https://www.bapscharities.org/about-us/ on 18 August 2024.

Brahmbhatt, Arun. 2014. “BAPS Swaminarayan Community: Hinduism.” Pp. 180-99 in Global Religious Movements Across Borders. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Correal, Annie. 2021. “Hindu Sect Is Accused of Using Forced Labor to Build N.J. Temple.” New York Times, May 11. Accessed from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/11/nyregion/nj-hindu-temple-india-baps.html on 25 September 2024.

Dwyer, Rachel. 2004. “The Swaminarayan Movement.” Pp. 180-99 in South Asians in the Diaspora, Histories and Religious Traditions, edited by Knut A Jacobsen and Pratap Kumar. Numen Book Series 101. Leiden: Brill.

Eastern Eye. 2016. “Mahant Swami Takes Charge.” Eastern Eye, August 19.

Kim, Hanna H. 2009. “Public Engagement and Personal Desires: BAPS Swaminarayan Temples and Their Contribution to the Discourses on Religion.” International Journal of Hindu Studies 13:357–90.

Mamtora, Bhakti P. 2016. “Swaminarayan and the Establishment of the Swaminarayan Sampraday (1801).” In Great Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History (Three Volumes), edited by Florin Curta and Andrew Holt. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. Accessed from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usyd/detail.action?docID=4743710 on 25 September 2024.

Marketwired. 2016. “Across America Devotees Grieve for Hindu Guru His Holiness Pramukh Swami Maharaj.” Marketwired. Accessed from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1813880488?pq-origsite=primo.

Patel, Aarti. 2018. “Secular Conflict: Challenges in the Construction of the Chino Hills BAPS Swaminarayan Temple.” Nidan: International Journal for Indian Studies 3:55–72.

Patel, Iva. 2022. “Swaminarayan.” Pp. 1581–85 in Hinduism and Tribal Religions, edited by Jeffery D. Long, Rita D. Sherma, Pankaj Jain, and Madhu Khanna. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Sadhu Amrutvijaydas. 2007. 100 Years of BAPS: Foundation, Formation, Fruition. Ahmedabad, India: Swaminarayan Aksharpith.

Sadhu Bhadreshdas. 2016. “Swaminarayan’s Brahmajnana as Aksharabrahma-Parabrahma Darsanam.” In Swaminarayan Hinduism: Tradition, Adaptation and Identity, edited by Raymond B. Williams and Yogi Trivedi. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Sadhu Vivekjivandas. 2024. “Gunatitanand Swami: A Brief Introduction (Part 1).” BAPS. Accessed from https://www.baps.org/EnlighteningEssays/2018/Gunatitanand-Swami–A-Brief-Introduction-(Part-1)-12812.aspx on 25 September 2024.

Swami Paramtattvadas. 2017. An Introduction to Swaminarayan Hindu Theology. Introduction to Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

The Sydney Morning Herald. 2023. “Police Release Images After Hindu Temple Vandalised.” The Sydney Morning Herald, May 13. Accessed from https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/police-release-images-after-hindu-temple-vandalised-20230513-p5d84t.html on 25 September 2024.

Williams, Raymond B. 2018. “An Introduction to Swaminarayan Hinduism.” Pp. 75-106 in An Introduction to Swaminarayan Hinduism. Third Edition. Introduction to Religion. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, Raymond B. 2004. “Terror Invades Paradise.” Pp. 131–37 in Williams on South Asian Religions and Immigration, edited by John R. Hinnells. New York: Routledge.

Williams, Raymond B. 2001. An Introduction to Swaminarayan Hinduism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Publication Date:

30 September 2024