KIM KŬM HWA TIMELINE

1931: Kim Kŭm Hwa was born in Korea.

1942: Kim showed a weak constitution, with a lingering illness.

1944–1946: Kim was married for the first time.

1948: Kim was initiated as a shaman by her grandmother.

1951: The Korean War began and Kim Kŭm Hwa fled to South Korea.

1954: The Korean War ended.

1956–1966: Kim was married for the second time.

1963: Park Chung-Hee was elected president of South Korea. He created the “New Community” movement, which sought to modernize South Korea. Korean Shamanism was considered a hindrance to modernization and the shamans were persecuted, including Kim.

1970s: Kim Kŭm Hwa won a national competition in cultural performance.

1981–1982: Chun Doo-hwan, president of South Korea, tried to revive Korean folk culture and performance. Kim Kŭm Hwa gained further recognition for her shamanic dance performance.

1982: Kim Kŭm Hwa gave her first performance in the United States as a cultural delegate for South Korea.

1985: Kim Kŭm Hwa was inscribed as Human Intangible Cultural Heritage no. 82-2 for her ritual mastership of Baeyŏnsin Kut and Taedong Kut, performed annually.

1988: Chun Doo-hwan lost power.

1990: South Korea gained a democratic government.

1994/1995: Kim Kŭm Hwa spoke at the International Women Playwrights Conference and performed her Taedong Kut in Perth, Melbourne, and Sydney, Australia.

1995: Kim Kŭm Hwa performed rituals for the deceased of the Sampoong Department Store collapse.

1998: Kim Kŭm Hwa performed the Chinogui ritual for dead North Korean soldiers in Paju, Gyŏnggi-do, South Korea.

2003: Kim Kŭm Hwa performed a ritual for the deceased of the Taegu Subway arson.

2006: Kim Kŭm Hwa initiated the first foreigner into Korean Shamanism, Andrea Kalff, a German, at her shrine on Kanghwa Island.

2007: Kim Kŭm Hwa published her autobiography.

2009: Kim Kŭm Hwa starred in Ulrike Ottinger’s documentary movie, The Korean Wedding Chest (Die Koreanische Hochzeitstruhe).

2012: Kim Kŭm Hwa accepted Hendrikje Lange, a Swiss, as her disciple.

2012: Kim Kŭm Hwa performed again the Kut for fallen North Korean Soldiers in Paju.

2012: Kim Kŭm Hwa performed the Baeyŏnsin Kut, which was recorded for a documentary for the Discovery Channel.

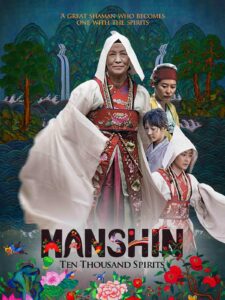

2013/2014: The biopic documentary, Manshin: Ten Thousand Spirits, premiered.

2014: Kim Kŭm Hwa performed rituals for the deceased of the Sewol Ferry tragedy.

2015: Kim Kŭm Hwa performed in Los Angeles, United States.

2015: Kim Kŭm Hwa performed at Festival d’Automne à Paris in Paris, France.

2019: Kim died in her home and shrine at Kanghwa Island, at the age of eighty-eight.

BIOGRAPHY

Kim Kŭm Hwa [Image at right] was born in 1931 during the Japanese occupation (1910–1945) in the southern part of the Hwanghae province in Korea (the current-day southwestern part of North Korea). Her maternal grandmother was the local shaman, which provided the young Kim with many opportunities to observe the different rituals performed.

Kim began to have health issues, as well as strange nightmares and visions when she was eleven years-old (Park 2013). In 1944 Kim’s father died when she was thirteen, leaving her mother to care for the family on her own. As a result, Kim was married off in order for her own family to make ends meet. Kim was abused by her new in-laws because they did not accept her poor health, which rendered her unable to work in agriculture. Kim’s marriage lasted only two years, and she was thrown out by her husband and his family, who annulled the marriage when she was fifteen years old.

She returned to her maternal home, where her illness and nightmares worsened. Her nightmares kept repeating themselves. She had frequent dreams about getting bitten by a tiger who was accompanied by an old man (Pallant 2009:24; Park 2013). Kim had visions even during her waking hours, and every time she spotted a knife, she felt compelled to grab it. Her grandmother eventually diagnosed the symptoms as spirit sickness (Sinbyŏng), which, according to shamanic tradition, occurs when one is called upon by the spirits to take up the duties of a shaman. Kim underwent her initiation ritual (Naerim Kut) in 1948 at the age of seventeen and began her tutelage under her grandmother to become a full-fledged shaman (Mansin/Mudang) (Kendall 2009:xx). Her grandmother became ill shortly after tutelage began, and Kim had to seek out another famous shaman in her area to complete her apprenticeship (Pallant 2009:24).

In 1948, the Korean peninsula was divided by the 38th parallel into North and South by the United Nations, which within a few years led to the Korean War (1950–1953). Many shamans were threatened by the military after being accused of spying on both sides, forcing them to evacuate their home communities. Kim, too, departed her northern home in 1951 for Inchŏn on the southern side. This displacement and trauma of experiencing the division of her country had a large impact on her later identity as a ritual professional (Park 2013). Kim Kŭm Hwa managed to establish herself as a ritual professional in Inchŏn and set up a shrine for her deities and rituals. But it was not without difficulty in the beginning. Being originally from the North, she was accused of being a communist and a spy (Park 2012).

In 1956, at the age of twenty-five, she met a man who lived nearby. He was determined to marry her, despite Kim being a shaman, and promised he would never leave her. Soon Kim entered her second marriage (Park 2013). Her husband did not keep his promise, however, and a few years after their marriage, he began to stay out of the house and come home late. Kim, aware of her husband’s infidelity, tried to salvage her crumbling marriage. After almost ten years of marriage, Kim and her husband divorced. He believed that he could not develop his career because he was married to a shaman, and therefore had to leave her (Park 2013; Sunwoo 2014).

President Park Chung-hee (1917–1979) led South Korea through “The New Community Movement” (Saemael Undong) in the 1960s and early 1970s. The movement tried to modernize South Korea, but old traditions, understood as superstitions, stood in the way. This resulted in a harsh crackdown on shamans and their way of life, for they were thought to be impeding the modernizing process. The police began to persecute and arrest shamans when they performed their rituals in the local villages. At the same time, an anti-superstition movement (Misint’ap’a Undong) rose among the police and ordinary citizens and resulted in shrines and other ritual items being burned or destroyed (Kendall 2009:10). This hardship also befell

Kim. Over the years she experienced several attempts from the police to stop her practice. Sometimes she managed to escape and sometimes she was caught. During one escape she had to leave all her religious paraphernalia at the house where she had been performing her ritual. [Image at right] Her only way to escape was through a window in the back of the house. She managed to hide in the nearby forest where she met up with her fellow ceremonial performers (Park 2013; “Renown Korean” 2015). As the negative sentiment towards shamans continued into the 1970s, Kim had to retreat to the forest when performing some of her rituals, away from the gaze of the police and villagers. However, the peace was short-lived as the number of evangelical Christian groups grew (Kendall 2009:10). They saw shamans as devil worshippers and therefore as a threat. During this time, Kim experienced several times when Christian groups tried to sabotage her rituals and urged her to go to church. During that time, Kim disdained the Christians and believed that there could not be a dialogue with them. In the 1990s and 2000s, however, Kim had speaking engagements at Catholic universities (Sunwoo 2014).

At the end of the 1970s, a newfound interest in Korean folklore among academic intellectuals began to grow. Following this, the idea that the shamanic ritual was a cultural art form began to appear. This became more prominent in the early 1980s. President Chun Doo-hwan (1931–2021) and his administration brought back traditional culture, which had been excluded during the New Community Movement (Kendall 2009:11, 14). Around the same time, Kim entered a national contest of performing arts where she performed one of her rituals. Kim won the contest for her beautiful and charismatic performance and earned national recognition as a cultural asset for her ritual mastery, but this recognition was as a cultural performer rather than as a shaman. Kim gained popularity and began to appear on a variety of television shows and in theatres to perform her rituals as a stage show (Song 2016:205). In 1982 Kim was invited to the United States as a cultural delegate, where she performed her rituals. Her performances received widespread attention, which continued after she returned to South Korea (Pallant 2009:25). In 1985, Kim Kŭm Hwa was recognized as “National Intangible Cultural Asset No. 82-2” as the ritual holder of Sŏhaean Baeyŏnsin Kut and Taedong Kut, abbreviated as “Fishing Ritual of the West Coast” (Seoul Stages 2019). Kim was the official ritual holder (one having attained mastership over specific rituals) of these two rituals from the 1960s until she died in 2019.

South Korea became democratic in the 1990s, and Kim was given the title of National Shaman (Naramudang), which allowed her to lead national ceremonies for pacifying the dead after horrific national calamities, such as the Sampoong Department Store collapse in 1995. The ceremony was broadcast nationally, and viewers were able to see Kim Kŭm Hwa ritually comforting the souls of the departed. Kim led similar rites after the Taegu Subway arson in 2003 and the Sewol Ferry tragedy in 2014 (Park 2013).

In 1995, Kim was invited to speak at the Third International Women Playwrights Conference in Australia. Kim accepted the invitation on the condition that the conference would arrange for her to perform Kut in some of the major cities in Australia. The conference, therefore, arranged for Kim to perform segments of Taedong Kut in Perth, Sydney, and Melbourne. The ritual was a celebration for the local community, which in this case was the major cities in Australia (Holledge and Tompkins 2000:60–63; Robertson 1995:17–18).

As mentioned earlier, the traumatic division of her nation and fleeing her home had a great impact on Kim’s identity as a ritual professional. In 1998, Kim performed Chinogui Kut (ritual for comforting the dead) for the fallen North Korean soldiers on the Southern side in Paju, Gyŏnggi-do. The purpose of the rites was to console the fallen soldiers after not being able to return to their homes, just like herself. At the end of the ceremony in 1998, Kim channeled the soul of the former North Korean leader Kim Il-Sung (1912–1994), who promised the audience that his son, Kim Jong-Il (1941–2011) would strive for unification. For Kim, performing the Chinogui ritual was an important part of her own identity and trauma, since she could feel the same pain that the fallen soldiers felt. Kim’s conducting of the Chinogui observance also became one of her annual rituals, which she kept performing until the end of her life (Park 2013).

In 2007 at the age of seventy-six, Kim published her autobiography, in which she recounted her life and career as a shaman. This autobiography also laid the foundation for the later biopic documentary directed by Park Chan-Kyung, Manshin: Ten Thousand Spirits.

In 2008 Kim’s ex-husband wanted to reconnect with her after a separation of nearly forty years. He had been followed by bad luck ever since leaving her. He had remarried and lost his wife after a few years of marriage when she passed away due to sickness. His businesses kept failing and he was now estranged from his children, which he believed was because he had left a shaman. He wanted Kim’s forgiveness, and for her to fix his bad luck, which she did. Until her death, Kim maintained a good friendship with her ex-husband, who often came and visited her at her shrine (Pallant 2009:25).

In 2009 Kim starred in Ulrike Ottinger’s documentary movie Die Koreanische Hochzeitstruhe (The Korean Wedding Chest). In 2012 Park Chan-Kyung began the filming of the biopic documentary Manshin: Ten Thousand Spirits. [Image at right] In the documentary, Kim Kŭm Hwa retold the story of her difficult life as well as how the division of Korea affected her. Kim invited Park to come and film her performing the Chinogui ritual for the fallen North Korean Soldiers in Paju as well as her performance and preparations for her annual Baeyŏnshin Kut, which ended up serving as a separate documentary for the Discovery Channel (Park 2012). Park Chan-Kyung’s documentary finished production at the end of 2013 and was released in theatres nationwide a few months later. That same year the Sewol Ferry tragedy happened, and Kim ritually comforted the souls of the deceased through her performance of Chinhon Kut (another ceremony for appeasing the deceased). Kim performed her last overseas tours in the United States at the Pacific Asia Museum at the University of Southern California and in Paris at Festival D’automne, performing the Mansudaetak ritual (USC Pacific Museum 2015; “Kim Kum-Hwa” 2015).

On February 23, 2019, Kim Kŭm Hwa passed away after a long illness at her home and shrine in Kanghwa Island (Creutzenberg 2019). Kim had specifically chosen her home to be at Kanghwa Island, located close to the border between South Korea and North Korea, not only because it was a spiritually strong location, but also because it was the place closest to her birthplace in the North (Pallant 2009:22).

TEACHINGS/DOCTRINES

Kim Kŭm Hwa never preached a doctrine or had a specific set of teachings. Like other shamans before her from the northern part of the Korean peninsula, Kim followed the Hwanghae tradition of Korean shamanism. The Hwanghae tradition, like the rest of the different Korean shamanic traditions, shares the fundamental belief that the world is full of spirits, deities, and the souls of the living dead. The shaman is the bridge between humans and all these entities as well as the mediator between the three realms: heaven, earth, and the underworld. The only way to mediate and navigate between these worlds and entities is through the shamanic ritual (Kim 2018:4).

What sets the Hwanghae tradition apart from other traditions found in the southern part of the peninsula, is that it largely relies on charismatic spirit possessions and the enshrinement of the shaman’s personal tutelary deities, which means that Kim like other Hwanghae shamans, had her own individual pantheon of deities, whose paintings adorned her shrine at Kanghwa Island (Kim 2018:6; Walraven 2009:57-59).

The Hwanghae tradition covered the geographical area starting from the Han River and going north through what today is North Korea. It was therefore only natural that this was the shamanistic tradition that Kim would be initiated into as a young girl and she would adhere to for the rest of her life (Walraven 2009:56).

The shamanic tradition of Korea has largely been considered a tradition that has passed on knowledge orally, however, the recording of Muga (songs/hymns) and Kongsu (oracles) has been maintained as a written tradition, also in the Hwanghae tradition (Kim 2018:2). Like shamans before her, Kim had her own collection of Muga and Kongsu, which she published in 1995. A shaman’s collection of songs/hymns and oracles are often passed down from master shamans to their successors depending on the rituals for which they become a ritual holder. Kim likely inherited her own songs/hymns and oracles from her maternal grandmother and the leading shamans who passed down the ritual mastery of Baeyŏnsin Kut and Taedong Kut. The different songs/hymns aid the shaman when performing the rituals, as they often describe or explain the ritual. The oracles help the shaman shift among the identities of the deities and spirits they call upon during the ritual and help adapt the speech from the deities and spirits into an understandable Korean language (Bruno 2016:121-26).

The way Hwanghae shamans enshrine their tutelary spirits and deities is via paintings called Musindo (spirit paintings). Musindo are an integral part of the Hwanghae tradition and their use of them dates back to the Koryŏ dynasty (918–1392) (Kim 2018:14; Kendall, Yang and Yoon 2015:17). The paintings not only represent the deities physically and visually but are likewise viewed as the embodiment of them, due to the shaman calling down the deities to reside in the paintings when they are hung up in the shrine.

The paintings are hung in designated places within the shrine, with the shaman’s main deities and tutelary spirits at the front and the more general ones at the back. Buddhist deities are in the far-left corner, and Mountain Gods and other deities of celestial objects are in the far-right corner of the shrine (Kim 2022:6). The paintings are produced in the form of a scroll, which makes it easy for the shaman to move the paintings to altars at ritual grounds away from the shrine, such as the ritual ground on a boat during the Baeyŏnsin Kut (as seen in image no. 2). The number of paintings varies according to the size of the individual pantheon of the shaman. A typical shrine’s collection of Musindo can consist of enshrined depictions of the general deities of importance in the Hwanghae tradition, such as The Seven Stars, Chinese General Spirits, the God of Smallpox, and the Dragon King; but can also consist of regional and personal spirits of importance, for example, in Kim’s shrine where paintings of General Im and her tutelary deity Tangun, ancestral shamans, and the local mountain god. (Kim 2018: 6-10; Walraven 2009: 60).

The paintings are commissioned by the shamans themselves or their clients and are produced by artists specializing in the making of shamanic paraphernalia. The painting, however, first becomes infused with spiritual significance when the shaman enshrines it and invites an assigned deity to come down and reside in it. The paintings are not passed on when a shaman dies. They are ritually burned or buried before the shaman dies, which is why it is rare to find Musindo that are older than the shaman who owns them (Kim 2018:7). Kim Kŭm Hwa probably also followed this tradition of burning or burying her own paintings before her own passing in 2019.

An integral and distinctive element of importance for the Hwanghae tradition is the practice of ritual charismatic spirit possession, which is found in all Kut (rituals) within this tradition. In ritual practice, the shaman invites the spirits of the deceased or deities to come and lament or give fortunes through the shaman’s body as the mediator in the form of speech or songs. When the shaman channels one of the deities in her paintings, the shaman will wear traditional clothing that corresponds to what the deity is wearing in the painting. This helps the shaman contact the deity and helps the assisting ritual professionals identify which deity has manifested by means of possession of the shaman. Furthermore, it also helps the onlookers follow which segment of the ritual the shaman has entered, since each segment is often dedicated to a specific deity (Kim 2018:9–12; Walraven 2009:61–63).

The charismatic possession not only functions as a way for deceased spirits to lament to the living, but also as a way of exorcising them so they can be sent off to paradise at the end of the ritual (Park 2013). Kim performed this type of charismatic spirit possession several times during her life for both the deceased North Korean soldiers at Paju, the deceased of the Sampoong Department Store Collapse, the Taegu Subway arson, and the Sewol Ferry tragedy to help the collective trauma of the deceased as well as of the living.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Kim Kŭm Hwa was famous for her vast repertoire and knowledge of Northern-style shamanic rituals, which means her style originated from the northern part of the Korean Peninsula. Out of all these rituals, she was most famous as the ritual holder of Sŏhaean Baeyŏnsin Kut, abbreviated as “Fishing Ritual of the West Coast,” for which she was designated as National Intangible Cultural Asset No. 82-2 (Creutzenberg 2019). The ritual originated from the coastal areas of Haeju, Ongjin, Hwanghae-do, and Yŏnpyŏng island, which is the coastal area and islands around Inchŏn, South Korea. Since being named National Intangible Cultural Asset No. 82-2 on February 1, 1985, the ritual has been performed annually at Inchŏn port under the management of Kim and the National Intangible Cultural Heritage West Coast Baeyŏnsin Kut and Taedong Kut Preservation Association (Korean National Cultural Heritage 2000; Park 2012). Originally Baeyŏnsin Kut and Taedong Kut took place on an auspicious date between January and March on the lunar calendar, but in the past decades, it has taken place on a suitable date between June and July on the Solar calendar (“National Intangible Cultural Property” 2000; Chongyo muhyŏng munhwa chae 82-2 ho 2022).

The purpose of Baeyŏnsin Kut is to ask the gods for good fortune and a satisfying catch for the coming fishing season. The ritual is performed for the local fishing community and boat owners. The main part of the ritual takes place in the boats while they are out on the sea, with the main boat containing the ritual space and altar (“National Intangible Cultural Property” 2000; Park 2012). As the ritual was formerly just performed for the local community, Kim gradually expanded it to become a public ritual, where everyone is welcome, including foreigners. Through English narration and a pamphlet, foreign audiences are led through the ritual on the same terms as the local Korean audience. By making the ritual a public event, Kim hoped for the younger generations to come and learn about the importance of the shamanic ritual both spiritually and culturally.

In recent years, it became quite a challenge to plan the ritual and get the needed sailing schedule, security clearance, and permissions. The ritual is typically held on large barges, which normally transport sand. Therefore, the barges do not have the needed security clearance to sail with passengers. Additionally, the permission to go out on the water also became difficult to get, due to the barges sailing close to the North Korean Sea border (Park 2012).

The patron deity, General Im, of Baeyŏnsin Kut is enshrined at Yŏnpyŏng island. The preparations for Baeyŏnsin Kut start each year with Kim and her disciples visiting the shrine and praying for a good ritual. From there on the preparations for the ritual are carried out at the association’s headquarters in Inchŏn. [Image at right] Everything from the right governmental application to the ritual paraphernalia is prepared. After praying at the shrine, an auspicious date for the ritual is set. Then the ritual holder has to consult the spirits through divination. When all that is finalized, the practical preparations begin in rehearsing the twelve different segments of the ritual. These include preparing sacrificial straw boats, finding and blessing a barge, and finally setting up the ritual site on the boat.

At first, Kim performed all twelve segments of the ritual by herself with the support of other local master shamans, but as she grew older, she passed on her knowledge of the different segments to her younger disciples and only performed a few segments herself, notably the first one dedicated to General Im, and the seventh and eighth segments, the centerpiece of the ritual, “The Nobleman’s Play” (Taegam nori) where the shaman thanks the local fishing community for their hardships in catching the fish. During the last years of her life, as Kim’s health declined, her niece and successor, Kim Hye-Kyung took over the leadership of the ritual (Park 2012; Chongyo muhyŏng munhwa chae 82-2 ho 2022).

The ritual consists of twelve segments, or minor rituals, with the first segment dedicated to General Im with the purpose of calling out the enshrined god. The segment takes place on land. In the second segment, the ritual entourage (consisting of the religious professionals, musicians, and audience) walks in procession down to the barge and brings the god on board. When the barge leaves the harbor, the third segment of the ritual begins. This consists of offerings made by the local fishermen for good fortune in the form of straw boats carrying food placed in the water. The boats are lit on fire for the smoke to reach the gods. The fourth to sixth segments call upon local gods, give fortunes to the audience, as well as provide breaks with food and drinks. The seventh and eighth segments contain the centerpiece of the ritual, which Kim herself, still performed until she could not perform anymore.

The ninth segment contains the tale of the Yŏngsan grandmother and grandfather and describes their separation and unification. The last three segments of the ritual wish for bounty from the ocean and the blessing of the gods. The ritual closes with sori, local song and dance by the fishermen and the ritual professionals who dance with the gods. The audience is also invited to participate and dress in shamanic robes (Park 2012; Chongyo muhyŏng munhwa chae 82-2 ho 2022).

Taedong Kut is typically performed the day following Baeyŏnsin Kut. Unlike Baeyŏnsin Kut, which takes place out on the water and is focused on the fishing community, Taedong Kut takes place on land and has the purpose of blessing the wider community as a whole, wishing for happiness and strengthening of the community and unification (National Intangible Cultural Property” 2000; Chongyo muhyŏng munhwa chae 82-2 ho 2022). Taedong Kut consists of twenty-four segments. The ritual shares most of its main segments with Baeyŏnsin Kut. Besides the shared segments, Taedong Kut also contains about twelve segments, in which the ritual professionals call upon the local gods of the area. In Kim Kŭm Hwa’s version of the ritual, local gods such as General Im, the local Mountain Gods, and Chinese general spirits are called upon. As in the Baeyŏnsin Kut, members of the audience are encouraged to participate and given fortunes throughout the ritual. The shaman also walks through the village area and blesses the different households. Again, the main part of the ritual is “The Nobleman’s Play” (Taegam nori), as well as the ritual for the Chinese general spirit who stands on knives. During this segment, the ritual professionals, like the deity, stand on knife blades to channel the spirit through their bodies. The ritual ends with the audience dancing along with the ritual professionals to send off the spirits and gods who participated in the ritual (Chongyo muhyŏng munhwa chae 82-2 ho 2022).

LEADERSHIP

Throughout her shamanic career, Kim Kŭm Hwa gained a small but devoted following of disciples and regular clients. Her disciples consisted of shamans-in-training, assistants, and musicians. The most important disciple is Kim’s niece, Kim Hye-Kyung, as she was appointed Kim’s successor and now has inherited the ritual mastership of Baeyŏnsin Kut and Taedong Kut, as well as the leadership of the Baeyŏnsin Kut Preservation Association (Pallant 2009:30; Park 2012, 2013). Along with her niece, Kim’s spirit-adopted son Cho Hwang-Hoon also plays a prominent role among Kim’s disciples. As the head musician of Kim’s group, he ensures that the orchestra functions correctly during rituals (Pallant 2009:25; Park 2012, 2013).

Kim’s leadership of the Baeyŏnsin Kut Preservation Association has played an important role in keeping the rituals alive. Through the association, Kim and her disciples managed all the administration and organizational work required for such large-scale annual ceremonies. It is also through the association that Kim taught her successor, disciples, and musicians the art of the ritual performance required to conduct the rites of Baeyŏnsin Kut and Taedong Kut (Park 2012).

Kim’s spiritual leadership also went beyond the South Korean national borders. She trained and initiated several Korean shamans, who set up their professional practices. Kim also trained foreigners, such as Andrea Kalff (German) and Hendrikje Lange (Swiss), whom she felt had the calling to become shamans. Kim spotted Kalff at an international women’s conference in 2005, where she observed that Kalff was suffering from spirit sickness. Kalff was initiated in 2006 and underwent an apprenticeship until Kim believed she was ready to set up her practice in Germany. It is not known exactly when Hendrikje Lange came into apprenticeship under Kim and if she ever was initiated or just became an assistant and musician for Kim, but we can assume that she became part of her practice a bit prior to the production of the documentaries.

Kim was very keen on telling her story of hardship and trauma, which not many shamans are. This has resulted in many academics, both Korean and foreign, taking an interest in her. Her willingness to let them into the world of Korean Shamanism and its rituals, during a time when most shamans would not like to draw attention, was significant (Park 2012; Park 2013).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Kim Kŭm Hwa struggled most of her life with her social status as a shaman, which resulted not only in persecution by different institutions but also provided a livelihood that required her to navigate between people’s conflicting attitudes regarding her profession, which both rejected it but also sought it. This struggle between public discursive opinion and the “secret” demand for ritual expertise has, since the early Chosŏn period (1392–1910), been the biggest challenge for Korean shamans and remains so today.

Korean Shamanism has always been present, with the earliest written records of its practice dating back to the Three Kingdoms period (57 BCE–668 CE). It is often identified as the indigenous religion of the Korean peninsula that stands in opposition to the imported religions of Buddhism and Confucianism. Korean shamanic practice was considered part of the state religion and flourished alongside Buddhism for a long period of time (Kim 2018:45–47). When the Neo-Confucian tradition became the state religion and ideology of the Chosŏn dynasty, the official view on shamans gradually began to change. During the reign of King Sejong (r. 1418–1450), shamans were officially banned from setting up shrines inside the walls of the capital. They were forced to move out of the walls if they wanted to practice. Following that, officials and especially their wives were forbidden to participate in shamanic rituals and visit the shrines outside the walls. The only shamans allowed to enter the city were the state shamans NSFW vee employed by the royal family to take care of certain state rituals within the capital. A few state-employed shamans were also allowed to practice certain state-sanctioned rituals in the provinces. Private Kut, on the other hand, were considered to be chaotic rituals, which did not belong in a harmonious Confucian society. Female shamans especially were considered a problem, due to their unruly nature in gaining people’s attention as well as hustling their clients for the best food and clothing, leaving them in poverty, which all went against Confucian doctrine (Yun 2019:49). Despite the Chosŏn government officially condemned support of the shamans’ practice, it was also dependent on the heavy taxes they placed on the practicing shamans, which was meant to discourage them. This extra income meant that the government would turn a blind eye to the shamans’ practice since it was more profitable than not having them practice. In the first half of the Chosŏn period, shamans still practiced without much legislation because of the tax. However, during its second half, and especially at the end of the eighteenth century, the government began to crack down on shamans due to the government increasingly finding the shamans to be more and more disruptive and greedy, despite them being taxed heavily (Baker 2014:22-26). Despite the crackdown, shamans still had clients seeking their help, even while public discourse about shamanism being superstition (Misin) was growing; this replaced the Confucian discourse of licentious rituals (Ŭmsa). This narrative was brought by the Christian missionaries and later picked up by Japanese anthropological researchers, who had an interest in documenting the irrational and superstitious practice of Korean indigenous religion during the Japanese occupation (1910–1945), which shaped the general understanding of shamanism (Yun 2019:50–55).

The Neo-Confucian doctrine that became the state religion and ideology promoted a certain social structure, which had to be upheld to keep a harmonious state and keep it out of chaos. This meant that the ruler was above subjects, husbands over their wives, and seniors over their juniors (Yao 2000:84, 239). Shamans upset this order by being predominantly female and the breadwinners of their families, which put them above their husbands. This not only created problems for the Chosŏn government, which saw the shamanic family construction as an obstruction to the harmonious society, but also could create problems for the husband, as it did for Kim’s second husband. His wife’s occupation made it impossible for him to find work himself, and people believed that it was bad luck to hire someone from a shaman’s family. Furthermore, shamans also upset the Confucian order due to what were considered to be licentious rituals, which were not a part of the Confucian ritual doctrine, which only permitted ancestral veneration and a certain set of state rituals led by men. All this together caused the government to crack down on the shamans’ practice and created a public conflicting attitude of the shamans being shunned, but also relied upon.

These conflicting attitudes very much persist today. These views often become apparent when people choose to sponsor a Kut. When sponsoring a Kut, there can be different specific reasons for it. It can be for turning a fortune, commemorating a death, or blessing a new business, which all require the shaman to perform an elaborate ritual that never comes cheap. It is the cost of these rituals that is linked to the notion of shamans’ greed. Moreover, clients will often deny or play down their belief in the shaman’s professional competence and powers and even show distrust despite needing the shaman’s services (Yun 2019:103–05).

Lastly, shamans like Kim faced the challenge of modernity and the newer generations’ lack of knowledge, which is expressed through the performance of public rituals such as the Baeyŏnsin Kut and Taedong Kut. When performing these rituals where the public is invited to be part of the audience, the reason for observing it is not in support of the religious tradition itself, but rather in curiosity or suspicion, which contrasts with the shamans who perform with the gods in their hearts (Kim, D. 2013). However, the shamans are aware that the audience does not have the same contextual understanding of the rituals as they do, and that makes it even more important for Kim, her successor, and other shamans to uphold these public rituals to show and broaden the audiences’, and especially the younger generations’, knowledge about Korean cultural heritage and religion (Park 2012, 2013; Kim, D. 2013). Besides promoting public rituals, Korean shamans have tried to encounter modernity and technology by promoting their practices on the social media platforms, such as Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube. Whether or not Kim used these platforms is not known, but she was never hesitant to appear on television or in documentaries to promote her rituals and inform the public about her belief system.

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGIONS

Throughout her life, Kim Kŭm Hwa was not only the protector and master of two intangible rituals but also helped revive interest in Korean Shamanism as a form of cultural performance and heritage, nationally and abroad. [Image at right] Despite her countless television and theatrical performances, Kim never considered her rituals as just performances. Every time she conducted a ceremony, whether on a stage or at a ritual site, she believed the gods and spirits were with her, and therefore, she performed with full authenticity (Robertson 1995:17–18). Most importantly, Kim preserved a ritual system that has faced hardship, change, and modernization.

Besides becoming a cultural icon, Kim also gained status as a national shaman, who dealt with national traumas, such as the division of the Korean peninsula, the Sampoong Department Store collapse, the Taegu Subway arson, and the Sewol Ferry tragedy. She not only handled the traumas of the division of the nation, which were personal to her as to other Koreans, through the Chinogui ritual, but also through more lighthearted rituals. The minor segment in Baeyŏnsin Kut of the grandmother and grandfather who had been separated and needed to find each other again, is an example.

Kim Kŭm Hwa’s role as a national shaman and intangible cultural heritage shows how important she and her skills have been to Korean cultural and religious identity, despite the Korean shamans’ continuously low status in society. Kim’s open-mindedness and desire for more international exposure to Korean Shamanism proved to be important. Her willingness as the first Korean shaman to admit foreigners into the tradition shows how important the continuation of the shaman’s role as intermediary for the Korean deities was for her.

IMAGES

Image #1: Kim Kŭm Hwa close-up image from the documentary Shaman of the Sea.

Image #2: Kim Kŭm Hwa performing gut. Photo by Ku-won Park, The Theatre Times.

Image #3: Kim Kŭm Hwa, on May 31, 2014, performing a ritual in memory of the more than 300 people who died in the sinking of the Sewol Ferry on April 16, 2014, at Incheon port, South Korea. Lee Jae-Won/AFLO, Nippon.news. https://nipponnews.photoshelter.com/image/I0000ZCzfPLYNnT0.

Image #4: Manshin film poster.

Image #5: Kim Kŭm Hwa performing Fishing Ritual of the West Coast in 1985. Korea National Cultural Heritage.

Image #6: Kim Kŭm Hwa performing a ritual in 1985. Korea National Cultural Heritage.

REFERENCES

Bruno, Antonetta L. 2016. “Translatability of Knowledge in Ethnography: The Case of Korean Shamanic Texts.” Rivista delgi studi orientali 89:121–39.

Chongyo muhyŏng munhwa chae 82-2 ho: Sŏhaean Baeyŏnsin Kut, Taedong Kut. 2022. Accessed from http://mudang.org/?ckattempt=1 on 10 August 2023.

Creutzenberg, Jan. 2019. “Shaman Kim Kumhwa Passed Away at Age 88.” Seoul Stages, February 28. Accessed from https://seoulstages.wordpress.com/2019/02/28/shaman-kim-kumhwa-passed-away-at-age-88/ on 10 August 2023.

Holledge, Julie, and Joanne Tompkins. 2000. Women’s Intercultural Performance. London, U.K.: Taylor & Francis.

Kendall, Laurel. 2009. Shamans, Nostalgias, and the IMF: South Korean Popular Religion in Motion. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Kendall, Laurel, Jongsung Yang, and Yul Soo Yoon. 2015. God Pictures in Korean Context: The Ownership and Meaning of Shaman Paintings. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Kim, David J. 2013. “Critical Mediations: Haewŏn Chinhon Kut, a Shamanic Ritual for Korean ‘Comfort Women.’” Asia Critique 21:725–54.

Kim Kŭm-hwa. 2007. Pindankkot Nŏmse: Nara Mansin Kim Kŭm-hwa Chasŏjŏn. Seoul: Saenggak ŭi Namu.

Kim Taegon. 2018. The Paintings of Korean Shaman Gods: History, Relevance and Role as Religious Icons. Kent: Renaissance Books.

“Kim Kum-Hwa: Shamanic Ritual Mansudaetak-gut.” 2015. Festival D’automne a Paris. Accessed from https://www.festival-automne.com/en/edition-2015/kim-kum-hwa-rituel-chamanique-mansudaetak-gut on 10 August 2023.

“National Intangible Cultural Property West Coast Baeyeonshin-gut and Taedong-gut.” 2000. Korea National Cultural Heritage. Accessed from http://www.heritage.go.kr/heri/cul/culSelectDetail.do?ccbaCpno=1272300820200&pageNo=1_1_2_0 on 10 August 2023.

Pallant, Cheryl. 2009. “The Shamanic Heritage of a Korean Mudang.” Shaman’s Drum 81:22–32.

Park Chan-Kyong, dir. 2012. Shaman of the Sea. Discovery Networks, Asia-Pacific. Seoul: Bol Pictures; Singapore: Bang PTE LDT. documentary. Accessed from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f60Lazcejjw&ab_channel=Viddsee on 10 August 2023.

Park Chan-Kyong, dir. 2013. Manshin: Ten Thousand Spirits. Seoul: Bol Pictures. Biopic documentary.

Walraven, Boudewijn. 2009. “National Pantheon, Regional Deities, Personal Spirits? Mushindo, Sŏngsu, and the Nature of Korean Shamanism.” Asian Ethnology 68:55–80.

“Renown Korean Shamanism Practitioner Kim Kŭm-Hwa Discusses History, Tradition, and the Future of Her Practice.” 2015. USC Pacific Asia Museum. Accessed from https://uscpacificasiamuseum.wordpress.com/2015/01/12/reknown-korean-shamnism-practioner-kim-keum-hwa-discusses-history-tradition-and-the-future-of-her-practice/ on 10 August 2023.

Robertson, Matra. 1995. “Korean Shamanism: An Interview with Kim Kum Hwa. Australasian Drama Studies 27:17–18.

Sunwoo, Carla. 2014. “Shaman Focuses on Unity, Healing.” Korea JoongAng Daily, February 27. Accessed from https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2014/02/27/movies/Shaman-focuses-on-unity-healing/2985599.html on 10 August 2023.

Yao Xinzhong. 2000. An Introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Dancing on Knives. 2012. National Geographic. Documentary. Accessed from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AAybclN6ugk&t=1s&ab_channel=NationalGeographicon 10 August 2023.

Kim Kŭm-hwa ŭi Taedong Kut. 2001. ArtsKorea TV. [Abridged recording of Taedong Kut.] Accessed from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_N5oyLuGGGM&ab_channel=ArtsKoreaTV on 10 August 2023.

Kim Kŭm-hwa. 1995. Kim Kŭm-hwa mugajip: kŏmŭna tta’e manshin hŭina paeksŏng-ŭi norae. Sŏul: Tosochulpan munŭmsa.

Publication date:

17 August 2023