LOMALAND TIMELINE

1847: Katherine Tingley, leader of Lomaland, was born.

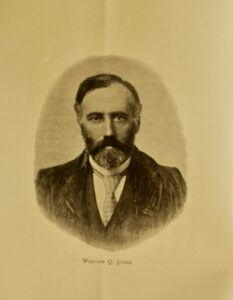

1851: W. Q. Judge, predecessor of Tingley as head of Theosophical Society, was born.

1874: Gottfried de Purucker, Tingley’s successor as leader of Lomaland was born.

1875: The Theosophical Society was founded in New York City.

1883: Judge revitalized the moribund Theosophical Society.

1894: Katherine Tingley joined the Theosophical Society.

1895: The Theosophical Society in America was formed under W. Q. Judge.

1896: W. Q. Judge died.

1896-1897: Tingley undertook a worldwide tour, called a Crusade.

1897 (February): A cornerstone laying ceremony for the School for the Revival of the Lost Mysteries of Antiquity (SRLMA), the organizational forerunner for the Lomaland community and educational system, was held.

1898 (February): Tingley and supporters renamed the Theosophical Society in America the Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Society at a convention in Chicago, which they invested with meaning as a crucial event in the grand cycles of time.

1898 (Summer–Fall): Tingley organized relief for soldiers from Spanish American War at Montauk Point, Long Island.

1911: The Point Loma site was legally named Lomaland.

1929 (July): Katherine Tingley died, and Gottfried de Purucker assumed leadership of Lomaland.

1942: Gottfried de Purucker died.

1942: Point Loma Theosophists relocated to Covina, California

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The first European expedition to come ashore in California did so at Point Loma. In Spanish, the phrase Point Loma means “Hill Point.” In Kumeyaay, the language of Native Americans in the vicinity, this location was called “Black Earth.”

Lomaland was the name of a Theosophical community located in Point Loma, an area at the northern end of the peninsula west of and across San Diego Bay from downtown San Diego, California. To the west of Point Loma lies the Pacific Ocean. At the time that Theosophists moved to Point Loma in the late 1890s and early 1900s, the area was mostly undeveloped. Theosophists planted fruit orchards and vegetable gardens, and trees and shrubs that eventually covered the entire Point Loma Theosophical community. The name Lomaland was made the legal name of this location in 1911.

The Theosophists who moved to Point Loma lived in many places across the United States, as well as in the United Kingdom and Sweden. They were members of a Theosophical organization led by Irish-American William Q. Judge (1851-1896), who was among the original group of individuals who began the first instantiation of the Theosophical Society in 1875 in New York City. The Theosophical Society experienced little growth in its first years in the United States. The twin founders of the Theosophical Society, Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831-1891) [Image at right] and Henry Steele Olcott (1832-1907), met while both were investigating Spiritualist phenomena. They left the United States for India in 1878. Judge took charge of the fledgling Society in the United States. Under his leadership it grew considerably, establishing local branches in cities across the country. Judge met Katherine Tingley (1847-1929), a New England social reformer, and was impressed by her abilities. When he died in 1896, she assumed the mantle of his leadership, although this was hotly contested by several other leaders at the time. Tingley was a visionary. She believed that she and her co-workers were destined to establish a beautiful, utopian city in the American West. When she and her party of several other Theosophists took a world-wide tour in 1896, called the Crusade, she met Gottfried de Purucker (1874-1942) while passing through California. The evidence is that she had sent an agent to find available land for the Society to purchase in California, but none could be found. De Purucker, living in Southern California at the time and an admirer of Tingley’s, told her about land at the northern end of the Point Loma peninsula. The envelope on which he drew a rough map of Point Loma became a treasured relic of the Point Loma tradition. Tingley’s agent bought the land and the Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Society (the name of Tingley’s organization after 1898) began the process of soliciting Theosophists across the United States to relocate to Point Loma. Theosophists believed that time passed in ever expanding and contracting cycles, and the year 1898 was especially propitious, as a new cycle of time was then dawning. Theosophists believed that advanced souls, called the Masters, guided Theosophists in all their endeavors. Since the time was right and the Masters supported their efforts, Point Loma was established in the last years of the nineteenth century. A formal ceremony recognizing the Theosophists’ new home, complete with Masonic rituals, was conducted in 1897.

Over the years, Lomaland grew in numbers.There was never a consistent effort to keep track of numbers of adults and children, but federal census records indicate that Lomaland at its height was comprised of several hundred adults and an even larger number of children. The children became the community’s primary focus. Lomalanders reasoned that if they were living in the dawn of a new cycle, then the children and youth would be the inheritors of the benefits of that cycle. Children then being born into human bodies were thought to be spiritually advanced over those in previous generations. Lomaland became, then, a sort of nursery for highly evolved human beings. Their parents and other caregivers hoped that when these children and youth matured to adulthood, they would become important leaders and role models for others in society.

Initially, Tingley and her fellow Theosophists wanted to begin an educational institution at Lomland modeled on the ancient mystery schools of antiquity. Such schools taught a form of gnostic metaphysics that emphasized the oneness of all things and the initiatory rites and practices that enabled mortals to tap into that oneness at a deep spiritual level. They named this institution the School for the Revival of the Lost Mysteries of Antiquity (SRLMA). This impressive name, unfortunately, could not save the SRLMA from devolving, over the years, into somnolence. But it served as a precursor for an educational operation that was far more effective than the SRLMA, namely, the Raja Yoga School.

Tingley [Image at right] attracted many educators to accept Theosophical teachings and move to Point Loma. These individuals became the nucleus for Lomaland’s Raja Yoga School. The phrase “raja yoga” from the Sanskrit was regarded by Lomalanders as a wholistic approach to educating people, cultivating the intellectual, spiritual, physical, and relational. At the beginning of Lomaland’s history, most pupils in the School were children of adult Theosophists who relocated their families to Point Loma. Boys and girls were raised and educated collectively and housed separately by gender. Reminiscences by those who grew up at Lomaland and in the Raja Yoga School contain common themes of group activities, such as hiking in San Diego County, creating art work, and giving dramatic performances and orchestral concerts. Children and youth in the School were provided an excellent education in the arts and humanities, by the standards of the day. That is due in large part to the talented adults who lived in Lomaland and were capable of taking young minds and educating them. Unfortunately, Lomaland did not have a comparable number of adults trained in various professions requiring mathematical and scientific skills.

As time passed and Raja Yoga pupils matured as teens and young adults, Lomaland leaders recognized the need to provide collegiate level instruction in subjects that university students in educational institutions across the United States might also study. These included mathematics, history, languages, and music and also subjects that would prepare them for the work world, such as shorthand and typing. And so in 1919 the Theosophical University was founded. It would give its name to Lomaland’s publishing arm, the Theosophical University Press, which has remained active. It was staffed by many of the same adults who had taught in the Raja Yoga School for many years, but also by younger Theosophists who had grown up at Lomaland.

After Tingley’s death in 1929, and under the leadership of her successor, Gottfried de Purucker, [Image at right] many former Raja Yogas married each other and moved away from Point Loma. Many simply settled in nearby San Diego or Los Angeles, while others went further afield. This was the 1930s, [the decade of the Great Depression, and young adults from Lomaland faced many of the economic challenges of that time that millions of other Americans were facing.

As for Point Loma, in the 1930s the resident population shrank, money-saving measures were adopted, and day-school children were allowed to matriculate, their parents paying Lomaland desperately needed cash for their children’s tuition. De Purucker was a self-taught polymath, especially adept at ancient languages and scriptures written in those languages. He had devoted many years of his life to the study of ancient languages as well as Theosophical texts by Blavatsky and other Theosophical writers. Before Tingley died, de Purucker began holding weekly study sessions to introduce Lomaland residents to the deeper aspects of Theosophical teaching. A committed group of young adults who were scribes and transcribers took their notes of de Purucker’s lectures and turned them into impressively lengthy tomes on all manner of things, from science, cosmology, and physics to ancient history, linguistics, and occultism. The first such book was Fundamentals of the Esoteric Philosophy, originally published in 1932. It was based upon lectures on Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine (1888) given by de Purucker between 1924 and 1927.

Lomaland continued to shrink throughout the 1930s. The general direction of the community changed from what it had been under Tingley’s leadership. As a social reformer, Tingley involved Point Loma Theosophists in various social causes that kept her at the forefront of news stories. She advocated peace during World War I, opposed vivisection of animals, and provided transformative education to youth and children. A more quietest approach to Lomaland’s relationship with larger society prevailed during de Purucker’s tenure. He focused instead on what they called “technical Theosophy.” Many Lomalanders had never studied Theosophical ideas and books in depth, content to abide by a simplified ethical perspective and general  conviction that Blavatsky’s teachings were true. The lecture series that de Purucker gave in the 1920s led to subsequent lectures converted into many books, some densely packed with Theosophical explanations of life, death, and the cosmos, and others designed more for a general readership of spiritual seekers yearning for certainty in a traumatic historic era.

conviction that Blavatsky’s teachings were true. The lecture series that de Purucker gave in the 1920s led to subsequent lectures converted into many books, some densely packed with Theosophical explanations of life, death, and the cosmos, and others designed more for a general readership of spiritual seekers yearning for certainty in a traumatic historic era.

De Purucker became well-known in among Theosophists worldwide for a movement he tried to begin and lead that was called the fraternization movement. His intent was to bring all Theosophists together into one overarching organization, all pulling in harness to bring Theosophy to the masses. However, this movement ran into resistance from Theosophists other than Lomalanders. The biggest opponent was Annie Besant (1847-1933), [Image at right] a British social reformer who accepted Theosophical teachings and became the leader of the Theosophical Society Adyar. This Society was based on the work of Blavatsky and Olcott in India. Adyar (now called Chennai), was a city in South India where the international headquarters of the Theosophical Society Adyar was located. Besant and Theosophy in India were linked to the Indian push for independence from Great Britain. But it was Besant’s approach to Blavatsky’s written works that caused upset and conflict among Theosophical traditions.

When Blavatsky died in 1891, Theosophists the world over generally agreed that Blavatsky’s most important written work, which came to have a canonical status in Theosophy, were Isis Unveiled (1877), [Image at right] The Secret Doctrine (1888), The Key to Theosophy (1889), and The Voice of the Silence (1889). Besant elaborated and extended Blavatsky’s teachings, although the Theosophical Society Adyar claims that she never departed from the content and intent of Blavatsky’s works. The Point Loma Theosophists, on the other hand, claimed to be teaching only what Blavatsky wrote, and blamed the Theosophical Society Adyar for inventing ideas not consistent with the Blavatsky corpus. A third major Theosophical tradition, the United Lodge of Theosophists (ULT), was established in 1909 by former Tingley supporter Robert Crosbie (1849-1919). The ULT claimed that only they follow the teachings in Blavatsky texts truthfully and completely. Given these divisions, it is not surprising that de Purucker’s efforts to start a fraternization movement, sincere and well-meaning as they might be, never really had a chance of succeeding.

Lomaland was situated at the northern end of the Point Loma peninsula. The rest of the peninsula was owned by the United States military. With the onset of America’s participation in World War II in 1941, Lomalanders feared that artillery and naval bombing practice might inadvertently damage Theosophical property. In 1942, the Theosophists, now bereft of de Purucker’s leadership when he died that year, left Lomaland and took up residence in a converted boys’ school in Covina, in the northern Los Angeles area. This spelled the end of Lomaland. The Point Loma tradition continued, but Theosophists have never returned to Point Loma in significant numbers with the intent of recreating Lomaland.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Among the most central doctrinal concepts in Theosophy are monism, rounds and races, Karma, and meaning.

Theosophy teaches monism, meaning only one supreme being or essence or energy exists, and out of this great oneness all things are derived. A monistic cosmos is a universe in which everything is connected. Any distinctions that we make are, ultimately, not distinctions at all, but merely illusory phenomena that human minds might want to see as more than one entity. This is the ancient teaching, theosophia or “divine wisdom,” known by sages, prophets, saints and priests. This concept resembles similar ones in Hindu and Buddhist cosmological assertions found in the ancient texts of South Asian traditions. Skeptics assert that Blavatsky borrowed monistic ideas from those traditions. Blavatsky and other Theosophists insisted that monism was central to the original “divine wisdom” that Theosophy teaches, and later religious traditions picked up on that divine wisdom. Theosophists thus have an easy answer to the question “Why do all religions bear some resemblance to one another?” It is because all religions have same primordial source. Blavatsky further insisted that the Masters conveyed this teaching to her. And their aid was essential. Blavatsky would have been the first to confess that she did not discover monism through her own research and study.

Rounds and Races is one of the most confusing and complex concepts in Theosophy. Theosophists believe that each world goes through a prescribed number of cycles that are millions of years in duration, and life forms evolve as the cycles march on. Blavatsky taught that we are currently in a special inflection point in the grand procession of cycles. Life forms in previous cycles have been accumulating spiritual and moral power over many lifetimes. Those now living are imbued with potential to do great good for all of life. The Masters provide the role model. They are like us, or rather, we are like them. They are simply a little further along the evolutionary path than we humans are, but we will eventually be Masters in turn, aiding the life forms who follow us in cyclic time.

The concept of Karma is also central to Theosophy. Belief in the oneness of all things means that any harm one does to another is also harm to oneself. This leads to the conclusion that all humans should be aiding and caring for one another at every opportunity. Indeed, that is what Point Loma Theosophists taught Lomaland children. From an early age children were immersed in a virtuous outlook. They were encouraged to look for the good in others, practicing the virtues of patience, compassion, among many others. Victorian values resembled these karmic counterparts in Theosophy, which arguably made it relatively easy for many middle-class Victorian adults to embrace Theosophy.

Life has profound meaning in Theosophy. All of our actions, from the smallest daily ones to the most important, life-changing ones, work to support divine oneness. This perspective supported a sense of individual worth as Theosophy offered a message of hope to each person that no one is worthless. Rather, we are of infinite importance in the grand scheme of things. This is the kind of viewpoint to which earnest people willingly devoted their lives. It was for these values that several hundred Theosophists from the United States and other nations heeded Tingley’s call to move to California and invest themselves in the community called Lomaland.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Lomalanders had daily devotionals, ritual meetings for special events, and artistic performances that might be regarded as not so much ritual but simply artistic expression. For Point Loma, however, these culturally significant performances passed as ritual in the life of the Lomaland community.

Daily devotionals usually occurred when all members of the community gathered at the Greek Amphitheater, modeled after ancient Greek amphitheaters, before the day’s work began. They would listen to a devotional reading, perhaps from one of Blavatsky’s books or from the Hindu classic, The Bhagavadgita, and answer roll call. Then members would go to the refectory for breakfast. Before eating they would talk about their motives for living a life of service but otherwise ate in silence and went about their daily tasks in silence as well.

Special occasions merited ceremonial displays, especially early in Lomaland’s history. The frequency of rituals seemed to be greater in the first years of Lomaland’s existence, although there is no quantitative data available to support that claim.

The birthdays of Theosophical leaders were officially observed. So were visits by well-known Theosophists not resident in Lomaland, or other noted visitors. On these occasions Tingley and other leaders would give speeches, and Point Loma residents (including Raja Yoga pupils) would provide musical interludes and perform in scenes from plays.

Musical and dramatic performances constituted an important part of Lomaland life. As noted above, a Greek amphitheater was built on Point Loma property. Ancient Greek plays were performed, as well as Shakespearean plays. The Point Loma orchestra and choir would provide music from the western canon of music. Lomaland was on the Pacific Ocean, which also touched the shores of Asia, and magazine articles often discussed oriental topics, but Lomalanders rarely acknowledged the value of Asian arts. Emphasis on western music and drama points to a fundamental tenet among Lomalanders: that Theosophical values and beliefs were coterminous with western art and philosophy. In general, Point Loma understood itself to be a beacon pointing back in history and forward into the future. In the past, Theosophy had deep roots in ancient, medieval, and early modern art and culture. In the future, Theosophy would play a key role in the transformation of civilizations.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

During W. Q. Judge’s time, Theosophists contributed to the growth of the Theosophical Society by participating in activities in their local lodges, such as regular meetings to hear lectures and discussion ideas. The Society’s headquarters were in New York City, along with an early lodge called the Aryan Theosophical Society, from which several Point Loma Theosophists came. Under Judge, Theosophists studied Blavatsky texts and also The Path, a periodical containing articles on both Theosophical teachings and current affairs. Local lodges were self-contained, and did not do much by way of reform other than establishing Theosophical Sunday Schools for children called Lotus Circles.

Enter Katherine Tingley, a larger-than-life boss with boundless energy and conviction in the rightness of her actions. She also had a profound spiritual side recognized by others. Most who knew her assumed she had powerful intuitive properties that enabled her to “read” and comprehend people at a much deeper level than most mortals could muster. Considerable controversy ensued when, after Judge’s death, Tingley made her move to assume control. Some leaders who were loyal to Judge left the organization, feeling that Tingley would take them down the wrong road. Others believed Tingley could do no wrong, and willingly heeded her call to move to Point Loma.

Both Judge and Tingley, as well as de Purucker after them, were Outer Heads of the Esoteric Section (also called the Eastern School of Theosophy) within the Theosophical Society. The Inner Heads were the Masters themselves. This esoteric sub-group, originally begun by Blavatsky, included members who later joined either the Point Loma tradition or the Theosophical Society Adyar. It was assumed that the Outer Head received messages and directions from the Masters. Hence, anyone disagreeing with the Outer Head was also going against the irrefutable teachings of the Masters. This linkage to the Masters was supported by the canonical texts written by Blavatsky.

After Blavatksy’s death, Judge tried to persuade Theosophists worldwide to recognize his leadership over all Theosophists. This led to a very complex moment in Theosophical history called the Judge case. Anyone who thinks that history is a simple matter should try reading the reams of material related to this case. The Besant-led Theosophists, of course, opposed Judge, and in the long run he convinced only a percentage of Theosophists in the United States and Europe to support him. These pro-Judge members, working for Theosophy in their local lodges, would be the followers whom Tingley would call upon to drop everything and move to Point Loma. Without Judge’s leadership, the community of Point Loma would never have materialized.

The organization of Point Loma was fairly standard for any such intentional community. Individual leaders were in charge of various departments: Raja Yoga education, maintenance of the grounds and buildings, harvesting of food and its preparation three times per day, and publication of Point Loma periodicals and various auxiliary Theosophical texts. Tingley kept a constant watch over all activities at Lomaland. Sometimes she was guilty of micromanaging, but if satisfied that someone was doing their job properly, she left them alone.

Money was always an important aspect of Lomaland. As noted below, Tingley sometimes stood to inherit money from deceased members. Lomaland also earned money by selling subscriptions to various magazines published and printed at Point Loma. In addition, books by Blavatsky and other Theosophical authors were sold. Lomalanders also contributed their own wealth, whether great or small, to the community.

Not only did Lomaland generate income, but it also saved money. The produce and other foodstuffs consumed by Lomalanders was grown on the Lomaland site. Other enterprises also saved money, such as wearing clothes made at Lomaland, and older children passing clothes down to younger ones. These attempts at self-sufficiency were never completely effective, but like other, similar groups, Lomaland attempted to become as self-sufficient as possible.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Tingley was in the news quite often. She was an outspoken public figure, always good for newspaper copy. For many years Point Loma owned an opera house in downtown San Diego where Theosophists would give speeches and perform plays and concerts. These events were open to, and targeted, the general public, and typically were favorably reported in local newspapers.

But Tingley wasn’t always cast in a positive light by reporters. She was embroiled in many court cases throughout her time as Point Loma leader. Three types of cases involved Tingley.

Some cases involved children and child custody. Point Loma provided an option for parents or relatives of children who for whatever reason needed a place to park their child or children. On the surface, the school system and living arrangements at Point Loma impressed middle-class people. In many respects, Point Loma was no different from hundreds of similar educational institutions at the time. But Tingley insisted on a rigid approach to moral behavior. Raja Yoga pupils were expected to adhere to ethical values that would today be called “Victorian.” In particular, she did not want sexuality to ever overflow its banks, but children and youth’s sexuality was impossible for her to control. Children, especially those approaching or in puberty, would masturbate at night, touch one another “inappropriately,” and form friendships, both same-sex and heterosexual, that Point Loma adults found dangerous and worthy of condemnation.

The nature of Point Loma’s location undoubtedly contributed to forbidden sexual activity. The community was situated on bluffs overlooking the Pacific beaches. Lomalanders often went to the seashore to swim and enjoy the waves. If supervision was lax at the beach, then teenagers might indulge in flirtatious and sexual behavior. Also, teens and young adults were unsupervised throughout much of any given day. They were responsible for bathing and dressing themselves, attending their classes, and working at community jobs. Generally adults knew where and when teens were supposed to be, but escaping the adult gaze was not that difficult, especially for a teen who was highly motivated and skilled at avoiding adult mentors.

Stories of various children who had tragic, even traumatic, experiences in the Raja Yoga School often ended with Tingley in court, defending Point Loma and her educators and caregivers. Children could only visit parents or other relatives for a few hours every Sunday afternoon. That provided little time for children to bond with parents. Often parents would hear about some incident involving sexuality and discipline as told by their own children, who might be punished in some fashion (such as being isolated in a locked room for hours or days) that parents would find disconcerting.

Tingley was also in court over child custody. Many orphans came to Point Loma. For example, the Theosophists in Buffalo, New York, had established an orphanage, and at the time they moved to Point Loma had nearly twenty infants, known among Lomalanders as the Buffalo Babies. These children remained at Point Loma until they were old enough to marry and move away. But other orphans at Point Loma did not always have as positive an experience. If parents or other caregivers were not available for contact, or mistreated their children when the latter visited them, then Tingley might try to persuade a judge to grant Lomaland care for these children. Those on the other side of such conflicts from Tingley might present a well-worn criticism of Tingley, that is, that she foisted an absurd, even evil, worldview on vulnerable children.

Tingley also appeared in court when one of the spouses in a marriage found Point Loma more to their liking than did the other spouse. Often the wife liked Point Loma and the husband did not. For many women, trapped in loveless marriages, and yearning for a deeper spirituality than conventional churches could provide, Lomaland was as close to an ideal home as any earthly place could be. Husbands, obviously, failed to appreciate the wonders of Lomaland, and even resented responsibilities assigned to them as long as they lived on the grounds.

A third category of court case that involved Tingley centered around inheritances. People who liked Point Loma while alive left their estates to Point Loma upon their deaths. Relatives of the deceased contested Tingley’s right to their deceased relative’s estate. Sometimes the monetary value of these estates was considerable. Tingley excelled at cultivating wealthy, cultured people, convincing them that she was one of them. At some level she probably believed that, but she appeared to others as a thief intent on getting a dead relative’s estate.

IMAGES

Image #1: Helena Petrovna Blavatsky.

Image #2: Katherine Tinsley.

Image #3: Gottfried de Purucker,

Image #4: Annie Besant.

Image #5: Front cover of Isis Unveiled.

Image #6: W. Q. Judge.

REFERENCES**

** Unless otherwise noted, the material in this profile is drawn from Michael W. Ashcraft. 2002. The Dawn of the New Cycle: Point Loma Theosophists and American Culture. Knoxville, TN: The University of Tennessee Press.

Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna. 1889 [1987]. The Key to Theosophy, being a Clear Exposition in the Form of Question and Answer, of the Ethics, Science, and Philosophy for the Study of Which the Theosophical Society Has Been Founded. Reprint. Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press.

Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna, The Voice of the Silence. 1889 [1976]. Reprint. Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press.

Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna. 1888 [1988]. The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion, and Philosophy. Two Volumes. Reprint. Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press.

Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna. 1877 [1988] Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology. Two Volumes. Reprint. Pasadena: Theosophical University Press.

de Purucker, Gottfried. 1932 [1979]. Fundamentals of the Esoteric Philosophy. Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Baker, Ray Stannard. 1907. “An Extraordinary Experiment in Brotherhood.” The American Magazine 63: 227-40.

Barton, H. Arnold. 1988. “Swedish Theosophists and Point Loma.” Scandanavian Studies 60.4: 453-63.

Greenwalt, Emmett A. 1978 [1955]. California Utopia: Point Loma: 1897-1942. Revised Edition. San Diego, CA: Point Loma Publications.

Kamerling, Bruce. 1980. “Theosophy and Symbolist Art: The Point Loma School.” Journal of San Diego History 26.4:231-55.

Kirkley, Evelyn A. “Equality of the Sexes, But…: Women in Point Loma Theosophy, 1899-1942.” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 1.2 (Apr. 1998): 272-88.

Small, Kenneth R. 2022. Theosophical History Occasional Papers Volume XV Revisiting Visionary Utopia: Katherine Tingley’s Lomaland, 1897-1942. Fullerton, CA: Theosophical History.

Spierenburg, H. J. 1987. “Dr. Gottfried de Purucker: An Occult Biography.” Translated by J. H. Molijn. Theosophical History 2.2:53-63.

Publication Date:

9 August 2023