WEBERITES TIMELINE

1725 (December 30): Jacob Weber was born in Zurich Canton, Switzerland.

1739 (August): Weber immigrated to Saxe Gotha Township, South Carolina with his older brother, Heinrich.

1747 (March): Jacob and Hannah Weber were married in Saxe Gotha.

1753: Jacob and Hannah Weber moved to the Dutch Fork with their two children.

1754-1756: Dutch Fork community remained unchurched after its failure to call John Jacob Gasser as minister.

1756 (May): Jacob Weber experienced a spiritual crisis and had a breakthrough.

1756-1759: Weber became a lay preacher and organized gatherings in his home.

1760 (February): Cherokee warriors killed dozens of Carolina backcountry settlers and put the Dutch Fork settlement on edge

1760-1761: The Weberites deified Jacob Weber and possibly John George Smithpieter,

1761 (February): The Weberites murdered Smithpieter and Michael Hans.

1761 (March-April): Jacob and Hannah Weber and two others were arrested, tried, and convicted of murder. Weber was executed on April 17; the three others were reprieved.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Named for their leader, Jacob Weber, the Weberites were a Christian religious group that briefly flourished in South Carolina’s Dutch Fork community between 1759-1761. They are remembered mainly for deifying Weber and ritually murdering two people, including one other leader who may have claimed to be divine. Weber and three others were tried and convicted of murder, and Weber was executed by provincial authorities. Though contemporaries saw them as deluded religious fanatics, the Weberites cannot be understood apart from the colonial southern backcountry’s unique institutional, geopolitical, and theological context. They were the product of an unchurched region beset by the terrors of the Cherokee War in a time of religious ferment and experimentation.

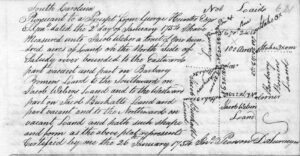

Jacob Weber was born in Stifersweil, Zurich canton, Switzerland in 1725 and was brought up in the Reformed Church. At age thirteen he immigrated to South Carolina with his brother, Heinrich, who was ten years his senior. They settled in Saxe Gotha township on the Congaree River, about one hundred miles inland from  Charleston. Heinrich died soon thereafter, and Jacob was bereft and, as he later wrote, “forsaken of man and without father or mother” (Muhlenberg 1942-1958:579). Little else is known of Weber’s early life. In 1747 he married, and around 1753 he and his wife, Hannah, moved to the Dutch Fork with their two children, where Weber had taken up land. [Image at right]

Charleston. Heinrich died soon thereafter, and Jacob was bereft and, as he later wrote, “forsaken of man and without father or mother” (Muhlenberg 1942-1958:579). Little else is known of Weber’s early life. In 1747 he married, and around 1753 he and his wife, Hannah, moved to the Dutch Fork with their two children, where Weber had taken up land. [Image at right]

The Dutch Fork took its name from its predominately German-speaking population and its location in the fork between the Broad and Saluda Rivers. These rivers converged about 125 miles northwest of Charleston to form the Congaree River. Now encompassed by Columbia, the state capitol, in the mid-eighteenth century the Dutch Fork was in the remote backcountry, a region of rolling hills and fertile soils but poor access to coastal markets, since it was by definition above the fall line, where shallows and shoals made the rivers unnavigable. Just south of the Dutch Fork, and below the fall line, stood Saxe-Gotha township. Established in 1738, Saxe-Gotha straddled the Cherokee trading path and was ideally situated for an inland trading center between piedmont and lowcountry. The Dutch Fork, Saxe-Gotha, and their environs were known more generally as the Congarees. Native peoples were driven out of the Congarees following the Yamasee War of 1718, though it remained on the margins of Catawba and Cherokee hunting grounds. Swiss and German immigrants poured into the region in the 1740s, drawn by generous land giveaways aimed at increasing Carolina’s white population and placing a buffer between the lowcountry plantation region and Indigenous peoples on its frontier. By the time Jacob Weber came of age and started a family, the lands in Saxe Gotha had all been granted, forcing him to move further inland into the more isolated Dutch Fork territory beyond the fall line.

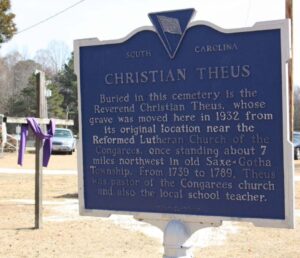

Religious institutions were generally weak in the interior, and the Congarees was no exception. Its German-speaking population was fairly evenly divided between Lutheran and Reformed. Though the Reformed contingent had a preacher, Christian Theus, he was ineffective. He stayed close to Saxe-Gotha and neglected the expanding settlements in and beyond the Dutch Fork, and he struggled to earn the respect of his people. According to Johann Bolzius, the Lutheran pastor of the Salzburger settlement in neighboring Ebenezer, Georgia, the Saxe Gothans treated Theus “with less respect than they do the humblest member of the congregation” (South Carolina Synod1971:63). The Lutheran half of the community was unchurched. In 1749, when some 280 Lutheran families petitioned Bolzius for help in organizing a congregation, he sent them a parcel of books but refused to help. Venting his scorn for them in his report to the missionary board, he called them swinish, filthy, disorderly, gotdless brutes. Unhappy with Theus and rejected by Bolzius, in 1754 a group of “divers Inhabitants and settlers” from the Congarees took matters into the own hands. Rallying around a former butcher and Swiss army chaplain named John Jacob Gasser, they petitioned the South Carolina Council for support for “a Church and school Master.” The petition was rejected, and Gasser’s efforts to get missionary funding from both Lutheran and Reformed churches in Europe also failed. As a result the people of the Congarees continued, as the Gasser petitioners wrote, “to Labour under a very great hardship for want of having the Gospel propagated and promoted in their Settlement” (South Carolina Council Journals 1754).

Around this time, Jacob Weber underwent a spiritual crisis. In typically Reformed fashion, he later recounted his conversion experience as unfolding in three stages. First, in the midst of his “adversity and suffering” following Heinrich’s death, he recalled how “the Lord God had compassion on me.” This compassion took the form of both mercy and judgment, grace and fear. Young Weber delighted in God, taking “more pleasure in . . . godliness, and in God’s word than in the world.” Yet at the same time, he wrote, “I was often troubled about my soul’s salvation when I thought of how God would require of me a strict accounting and how I would then hear the judgment pronounced upon me, not knowing what it would be.” Weber tried to justify himself by his own good works, an exercise that left him uncertain of his fate, for he was “inclined towards love of the world” by his “corrupt nature.” Observing the “externals,” Weber constantly suspected that he was simply religious, not converted. These suspicions turned to terror in the second stage of his conversion experience, probably when he was around thirty years-old, as he came “through a stirring of [his] heart” into a painful awareness of his sin. “I realized how terribly the human race has fallen from God and also how deeply all of us without exception are sunk in corruption by our very nature.” Withdrawing into prayer and silence, Weber “forgot all the tumult of the world so that I felt as if God and I were alone in the world.” He now realized that only “being born again of water and the Spirit” could save him. He began to pray more fervently and was further convicted of his sinfulness, so that he felt that he “deserved a thousand times to be cast out by God” and saw “that the whole world was in wickedness.” This “horrible realization” led him deeper into prayer, after several days of which he “passed from death to life.” And thus he reached the third stage, assurance of his salvation, sometime in May of 1756. The “peace and communion with God” that followed, grounded in the “Blood-surety of Jesus,” bore him through two years of “much cross and many burdens” (Muhlenberg 1942-1958: 578-80).

Remarkably, Weber sustained and articulated this experience with no guidance from clergy and no model from a congregation; indeed, in a “godless” frontier setting where each person, as Bolzius claimed, inhabited “his own wilderness” (Jones 1968-1985:XIV, 52). His strong mystical bent, sincere piety, exceptional self-awareness, and solid foundation in Reformed and Pietist traditions made an impression on his family and friends. Not long after his passage from death to life, Weber started meeting with his neighbors for worship in his home, where they sang psalms and heard sermons read by Weber.

Weber’s spiritual transformation and house church coincided with a period of extraordinary violence in the Carolina backcountry: the Cherokee War of 1760-1761 (Tortora 2015:146). [Image at right] As early as 1756, news of the “impending Danger” of a French and Indian assault on the Congarees reached provincial authorities. In January 1757, bands of unidentified Indigenous warriors plundered, burned, and finally drove settlers from the upper Broad and Saluda Rivers, causing such “unspeakable Uneasyness” in the Dutch Fork “that almost the whole Place threatens to break up, declaring they cannot possibly stay much longer, for Fear worse should happen” (McDowell 1970:324-25). In response, Dutch Fork settlers began construction on a fort. But the worst was yet to come. Though the neighboring Cherokee had remained neutral during the conflict, in 1759, British-Cherokee relations broke down. Cherokee warriors raided the frontier settlements. They killed fourteen white settlers in western North Carolina, renewing fears that “Broad River and Saludy will get a Stroke soon” (McDowell 1970:485). The stroke came in February 1760, when a Cherokee war party fell on the South Carolina frontier and killed dozens of settlers. Refugees abandoned the backcountry and fled to Saxe-Gotha and the distant lowcountry. Rumors that the Creeks might join the French and Cherokees kept tensions at a fever pitch into the summer of 1760. Although the immediate threat to the frontier subsided soon thereafter, it took another year for the British to mount a decisive campaign and pacify the Cherokee.

Weber’s spiritual transformation and house church coincided with a period of extraordinary violence in the Carolina backcountry: the Cherokee War of 1760-1761 (Tortora 2015:146). [Image at right] As early as 1756, news of the “impending Danger” of a French and Indian assault on the Congarees reached provincial authorities. In January 1757, bands of unidentified Indigenous warriors plundered, burned, and finally drove settlers from the upper Broad and Saluda Rivers, causing such “unspeakable Uneasyness” in the Dutch Fork “that almost the whole Place threatens to break up, declaring they cannot possibly stay much longer, for Fear worse should happen” (McDowell 1970:324-25). In response, Dutch Fork settlers began construction on a fort. But the worst was yet to come. Though the neighboring Cherokee had remained neutral during the conflict, in 1759, British-Cherokee relations broke down. Cherokee warriors raided the frontier settlements. They killed fourteen white settlers in western North Carolina, renewing fears that “Broad River and Saludy will get a Stroke soon” (McDowell 1970:485). The stroke came in February 1760, when a Cherokee war party fell on the South Carolina frontier and killed dozens of settlers. Refugees abandoned the backcountry and fled to Saxe-Gotha and the distant lowcountry. Rumors that the Creeks might join the French and Cherokees kept tensions at a fever pitch into the summer of 1760. Although the immediate threat to the frontier subsided soon thereafter, it took another year for the British to mount a decisive campaign and pacify the Cherokee.

It is not certain that Weber and his followers took an apocalyptic view of the Cherokee War, but this was the context in which they “formed a Sect of Enthusiasts,” in the words of their most reliable witness, South Carolina Lieutenant Governor William Bull (Bull to Pitt 1761). The sources give widely varying accounts of the Weberites’ beliefs, practices, and crimes, but they all agree on one key point: that both Weber and his followers deified him as the “most High,” God the Father (Bull to Pitt 1761). This claim may have originated with one follower in particular, John George Smithpieter, who Weber later blamed as the “author and instrument” of his misfortunes (Muhlenberg 1942-1958:579). According to several sources, Smithpieter also deified himself, claiming to be Jesus the Son. Saxe Gotha minister Christian Theus reported an encounter with the Weberites, in which Smithpieter addressed him as “little parson” and asked, “do you believe that I am the redeemer and savior of the world and that no man can be saved without me?” (Muhlenberg 1942-1958:579). When Theus rebuked him, the Weberites threatened to kill him, and he narrowly es:caped. Smithpieter probably orchestrated the murder of Dutch Fork settler Michael Hans, a “lukewarm” follower who may have questioned Weber’s and Smithpieter’s divinity. On February 23, 1761, Hans was smothered between two mattresses (French 1977:277). The following day, Jacob Weber declared Smithpieter was “the old Serpent, and unless he was put to death, the World could not be saved.” As Bull described it, “the deluded people immediately seized Smith Pieter, and with all the rage of religious persecution, beat him to death without remorse” (Bull to Pitt 1761).

On March 5, Weber and six of his followers were arrested for murder. They were tried in Charleston on March 31, and Weber and three others (his wife Hannah, John Geiger, and Jacob Bourghart) were found guilty and sentenced to death (South-Carolina Gazette 1761). The crown granted a reprieve to the three accomplices, whom Bull claimed were acting on Weber’s orders. Weber was hanged on April 17. In his jailhouse confession, he gave a detailed account of his spiritual journey and conversion, blamed Smithpieter for his “great calamity” and “ghastly fall,” and assured his children and followers that he had come to his senses, realized his sin, and been restored to God’s favor. “I am again experiencing the testimony of the Holy Spirit,” he declared. “The Spirit of God is bearing witness with my spirit that I am the child of God” (Muhlenberg 1942-1958:579).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Weber’s spiritual autobiography showed the basic hallmarks of his Reformed Protestant background, namely, a belief in the pervasiveness of sin and an absolute dependence on the free grace of God and merits of Christ, not good works, for salvation. It also showed clear influence from the evangelical and pietist movements that swept the Atlantic world in the mid-eighteenth century. His conversion was grounded in religious experience; his narrative gave agency to the Holy Spirit for fostering conviction and bringing joyful, peaceful assurance of salvation. His was a deeply personal story of adversity and suffering, pride and humility, and alienation from and communion with the divine. It was loaded with emotion, describing his fear and horror, guilt and sorrow, “unspeakable joy,” the pleasures of piety, and a longing for and clinging to the “Blood-Surety” of Jesus (Muhlenberg1942-1958:579). Thus the Weberites’ more unconventional beliefs and practices, extreme though they were, were grounded in an orthodox Reformed tradition tempered by moderate evangelical and pietist emphases on religious experience.

Their unorthodox beliefs, namely the deification of Weber and the identification of Smithpieter with Satan, have no direct parallels in the eighteenth-century backcountry. However, they do drink from the same prophetic and millenarian well as radical evangelicals and pietists, both of whom had a strong presence in the backcountry generally and the Dutch Fork in particular (Little 2013:170-73). Indeed, continental Radical Pietism appears to be a key source of Weberite beliefs and practices. This far-flung movement flourished in the Netherlands, the German Palatinate, and parts of Switzerland in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries; it also had adherents in Britain and British North America. Like their Pietist cousins in the Lutheran and Reformed churches, Radical Pietists emphasized small group meetings, conversion, personal piety, and religious experience and feeling, but they departed from mainstream Pietism in a number of ways. Radicals were typically separatists who distrusted organized religion; they had a strong millenarian streak; and their chief messengers were uneducated, itinerant lay preachers, not ordained clergy. Beyond these basic similarities, Radical Pietists were distinguished by a number of more heterodox practices. Some, like the Dunkers or Church of the Brethren, practiced adult baptism by threefold immersion. Others celebrated the Sabbath on the seventh day, practiced ritual foot washing, held love feasts, believed in universal salvation, preached celibacy, or strove for sinless perfectionism. Many emphasized direct revelation from the Holy Spirit; given to visions and ecstatic utterances, some, like the wandering Inspirationists, traveled from town to town and trembled as they prophesied.

The Weberites belonged in spirit to this broad stream of Radical Pietist belief and practice. They were clearly anti-institutional and disdainful of ordained clergy, having rejected the church’s salvific role in general and shown their utter contempt for Christian Theus in particular. Their prophetic and millenarian tendencies were self-evident, given their identification of Smithpeter with the “old Serpent” of the book of Revelation, whose destruction signaled the last judgment and the coming of the New Jerusalem. Moreover, these connections between the Weberites and Radical Pietism are not merely theoretical, for there is ample evidence that such ideas entered the Carolina backcountry in the mid-eighteenth century as Radical Pietists settled or passed through the region.

Contemporaries were certainly not surprised to find “a sect of Enthusiasts” in the unchurched backcountry. According to the Anglican priest Charles Woodmason, who itinerated in the backcountry in the late 1760s, “Africk never abounded with New Monsters, than Pennsylvania does with New Sects, who are continually sending out their Emissaries around.” Among these emissaries were the “Gifted Brethren (for they pretend to Inspiration),” who “now infest the whole Back Country, and have even penetrated South Carolina (Woodmason 1953:78). Woodmason was fond of hyperbole, but he was not far from the mark in connecting Pennsylvania to the Dutch Fork. One emissary in particular was Israel Seymour, a fugitive from the Ephrata community, a Radical Pietist commune in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Seymour was a man of “special natural gifts” (Lamech and Agrippa, 197) who was ordained at Ephrata and quickly gained a following there. He ran afoul of the leadership, however, and fled to South Carolina. There he settled in a community of Seventh Day Baptists on the Broad River opposite the Dutch Fork. Members of this congregation also had ties to Ephrata and had migrated from Pennsylvania in the early 1750s. The eighteenth-century Baptist historian Morgan Edwards described Seymour as “a man of some wit and learning, but unstable as water” (Edwards 1770:153-54). It is certainly possible that Weber came into contact with the Ephrata Sabbatarians; he may well have been influenced by the charismatic preaching of Seymour, who served the Broad River congregation in the mid-1750s, during Weber’s spiritual crisis. There is no direct evidence that the Weberites adopted the peculiar practices of this sect, which included love feasts, ritual foot washing, pacifism, and seventh-day worship, but Weber would have found something familiar in their Reformed sentiments. In addition to the Broad River Sabbatarians, there were congregations of Dunkers in the vicinity of the Dutch Fork, with whom Weber could easily have had contact. Weber hardly had to leave the Dutch Fork to gain access to a range of Radical Pietist influences, from the simplicity and intimacy of the Dunkers to the inspired, prophetic preaching of Seymour and the mysticism of the Ephrata emissaries.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

There are few description of the Weberites’ practices. Much of what is known about their rituals is based on second- and third-hand accounts from hostile sources and must be taken with a grain of salt. There is some agreement, however, about the ritualized murder of Hans and Smithpieter. Hans was smothered between two mattresses, presumably as a punishment for lukewarmness or defiance. Smithpieter was beaten and stomped to death, in one account after being chained to a tree. The chains probably symbolized the binding of the “old serpent,” Satan, with chains in the book of Revelation. Other sources charged that the Weberites practiced ritual nakedness and indulged in the “most abominable wantonness” (Muhlenberg 1942-1958:578).

The Weberites’ willingness to violate carefully guarded sexual taboos and engage in ritual murder points to an extreme form of antinomianism that is not uncommon among groups who practice self-deification. Like the medieval Brethren of the Free Spirit and the Ranters of Civil War-era England, the Weberites, by claiming to be divine, achieved complete moral and spiritual freedom. They were one with God, and God was in and through all things, so that nothing was impure, unclean, or off-limits. The spiritual liberation of such antinomian groups might take the form of unbridled hedonism, ritual nakedness, free love, ostentatious dress, even murder, all practiced without remorse. Indeed, the Weberites were fully convinced that they were right to murder Smithpieter and were brought to their senses only after being found guilty and sentenced to death.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

There is no record of any formal organization among the Weberites. They were a religious group centered around the personality and subject to the authority of one or more deified leaders. Some questionable accounts mention a third such leader, possibly named Dauber, who made up the third member of the Trinity; this claim is not substantiated by the early sources (Carpenter n.d.:3-8). Weber’s wife Hannah was also said to be the Virgin Mary, though given the Weberites’ Reformed background, this was unlikely. The only eyewitness to the their practices, Christian Theus, described a meeting or service in which the leaders sat on a raised  platform and the followers sat at their feet. After Theus rebuked Smithpieter, the leaders found Theus guilty and sentenced him to death, but the mode of execution (by hanging or drowning) was decided by the congregation. [Image at right] At trial, Weber was found to have given the order to kill Smithpieter, and his followers carried it out. For the most part, the Weberites recognized a clear line of authority from the deified Weber to his followers, though this authority was contested by Smithpieter with his competing claim to divinity.

platform and the followers sat at their feet. After Theus rebuked Smithpieter, the leaders found Theus guilty and sentenced him to death, but the mode of execution (by hanging or drowning) was decided by the congregation. [Image at right] At trial, Weber was found to have given the order to kill Smithpieter, and his followers carried it out. For the most part, the Weberites recognized a clear line of authority from the deified Weber to his followers, though this authority was contested by Smithpieter with his competing claim to divinity.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

The Weberites faced numerous challenges in their short life. They were made up of common farming people who, as Bull noted, were “long known” to be “orderly and industrious members of civil society,” though they were also “very poor” (Bull to Pitt 1761). They were lured to a remote and unsafe frontier by coastal elites who used them as a buffer against the enslaved and Indigenous peoples they were exploiting, and who ignored the civil and religious needs of backcountry settlements. Longing for a connection with the divine, they founded their own church, drawing from the mystical and evangelical currents that flowed through the region. In a time of extreme danger and instability, they deified their leader and murdered his enemies. The group died out after Weber’s death.

IMAGES

Image #1: Jacob Weber’s Plat for 100 acres on the Saludy River in the Dutch Fork, 1754. Courtesy of South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

Image #2: Cherokee headmen, 1762.

Image #3: Christian Theus historical marker, Gaston, South Carolina.

REFERENCES**

** Unless otherwise noted, the material in this profile is drawn from Peter N. Moore. 2006. “Religious Radicalism in the Colonial Southern Backcountry.” Journal of Backcountry Studies 1:1-19.

Bull, William to William Pitt. 1761. Records of the British Public Records Office related to South Carolina, 1663-1782. Volume 29:80-82, April 26.

Carpenter, Robert. n.d. “Rev. Johann Frederick Doubbert, Early German Minister – Radical Weberite or Respected Charleston Minister?” Unpublished typescript.

Edwards, Morgan. 1770. Materials toward a History of the Baptists, Volume 2, South Carolina and Philadelphia. Reprinted in Danielsville, GA, 1984.

French, Captain Christopher. 1977. “Journal of an Expedition to South Carolina.” Journal of Cherokee Studies II:274-301.

Jones, George Fenwick, ed. 1968-1985. Detailed Reports on the Salzburger Emigrants who Settled in America . . . edited by Samuel Urlsperger. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press,.

Lamech and Agrippa. 1889. Chronicon Ephratense: A History of the Community of Seventh Day Baptists at Ephrata. Translated by J. Max Hark. New York. Reprinted New York: Burt Franklin, 1972.

Little, Thomas J. 2013. The Origins of Southern Evangelicalism: Religious Revivalism in the South Carolina Lowcountry, 1670-1760. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

McDowell, William Jr., ed. 1970. Documents Relating to Indian Affairs, 1754-1765. Columbia, SC: South Carolina Archives Department.

Muhlenberg, Henry Melchior. 1942-1958. The Journals of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg. Volume II. Translated by Theodore G. Tappert and John W. Doberstein. Philadelphia: Evangelical Lutheran Ministerium of Pennsylvania and Adjacent States.

South Carolina Council Journals. 1754. Columbia, SC.: South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

South-Carolina Gazette, April 25, 1761.

South Carolina Synod of the Lutheran Church in America. 1971. A History of the Lutheran Church in South Carolina. Columbia, SC: by the author.

Tortora, Daniel J. 2015. Carolina in Crisis: Cherokees, Colonists, and Slaves in the American Southeast, 1756-1763. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Woodmason, Charles. 1953. The Carolina Backcountry on the Eve of the Revolution: The Journal and Other Writings of Charles Woodmason, Anglican Itinerant, edited by Richard J. Hooker. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Publication Date:

1 August 2023