MOLOKANS TIMELINE

1765: The first mention of the Molokans was in a report to the Synod of the Tambov consistory.

1805: The Molokans received relief under Alexander I, as they were granted permission to move to Molochnye Vody.

1830s: The Molokans were classified as a “most dangerous sect” under Nicholas I; the group was persecuted by the state, and exiled to Transcaucasia.

1830-1840: There was a mass migration of Molokans to Transcaucasia.

19th century (mid-years): There was an emergence and active spread of Molokans Jumpers in the Transcaucasia.

1905 (April 17): Tsar Nicholas II issued a decree of religious liberty.

1905: The All-Russian Congress of Molokans in Vorontsovka was devoted to the centenary of granting religious freedom to the Molokans in Russia.

1901-1911: There was a migration of Molokans to California, U.S.

1921: A proclamation was issued To the sectarians and Old Believers living in Russia and abroad, which cancelled all restrictions on non-Orthodox believers. The Union of Spiritual Christians Molokans was re-established.

1929: In the Soviet Union, “sectarians” were forbidden to form their own economic and production associations and cooperatives.

1950s: About 700 Molokans moved from Iran to California.

1961: Molokans from Turkey relocated to the Stavropol Region of the USSR.

1964: Migration of Molokans from the United States to Australia began after a prophecy.

1980s-1990s: There was a mass exodus of the Molokans from Transcaucasia to Russia, U.S., and Australia.

1991: The Union of Spiritual Christians of Molokans of Russia was re-created.

2000s: There was a significant decrease in the number of Molokans in the Transcaucasia region.

2005: The World Congress of Spiritual Christians of Molokans was “dedicated to the 200th anniversary of granting the Molokans freedom of religion” in the village Kochubeevskoe of the Stavropol Region.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Traditionally in historiography, Molokan Spiritual Christianity refers to the old Russian sectarianism along with Dukhobors, Subbotniks (Sabbatarians), Khlysts, Skoptsy, and some other movements. There are several versions of the origin of the name “Molokan” (“milk drinkers”). Most likely, the official authorities used that term because they did not adhere to the church fasts and consumed on fasting days meat and milk. The Molokans themselves explain it by quoting from the Bible: “Like newborn babies, crave pure spiritual milk, so that by it you may grow up in your salvation” (1 Peter 2:2). According to another version, the name was finally assigned to them in the early nineteenth century in connection with their mass resettlement to the Molochnye Vody River in the Taurida Governorate. Another folk version states that this is how the local administration told them: “malo kanuli” (“few of you have disappeared”).

The exact time and place of origin of the Molokan religion are unknown. [Image at right] It is usually thought that it appeared in Central Russia in the middle of the eighteenth century. In 1765, the word “molokaniya” is used for the first time in the reports to the Synod of the Tambov consistory about dissenters (Bonch-Bruevich 1973:247). The founder is considered to be the tailor Semen Matveevich Uklein (1727-1809), a resident of the village of Uvarovo, Tambov Province. He was married to the daughter of the Dukhobor leader Illarion Pobirokhin and was himself a member of the Dukhobor movement (Doukhobor). He later developed his doctrine within the framework of spiritual Christianity. In Dukhobor doctrine, Uklein rejected the idea of a “living Christ” embodied in the leaders of the doctrine and regarded all men as sons of God, equal among themselves. The true Church, according to Uklein, is based only on the Bible. From Tambov Province, the movement spread to the neighbouring provinces of Saratov, Voronezh, Astrakhan, and others.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the movement split into different currents: Molokans of the Don Persuasion (molokane donskogo tolka), the Molokan Subbotniks, the Jumpers (pryguny), the Communalists (obshchie), and etc. None of them was leading or predominant. After the separation of the Molokan groups and especially the Jumper movement, the remaining part of the Molokans was called Constant Molokans (postoyannye) (Klibanov 1965:146).

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Molokans had become a notable phenomenon in the Tambov, Voronezh, and Saratov Provinces. According to Molokan legends and manuscripts, in 1805, Alexander I (1801–1825) issued an imperial decree that granted the Molokans limited recognition and religious freedom. In 1905, 1955, and 2005, Molokan congresses celebrated the centennial, sesquicentennial, and bicentennial anniversaries of this decree (Clay 2012). Under the relatively tolerant reign of Alexander I, the government organized the relocation of “sectarians” to the outskirts of the empire to limit their influence. Dukhobors and Molokans were allowed to move to Taurida Governorate, and a significant number of Tambov Molokans moved to Molochnye Vody.

Under Nicholas I in the 1830s, the movement (along with the Dukhobors and Subbotniks) was categorized as the “most dangerous sect”. The Molokans not only were forbidden to disseminate their teachings, but also prohibited from worship, performing rituals, holding public positions, and having Orthodox workers. The government also subjected them to severe economic sanctions. They recommended sending the “sectarians” enlisting for military service to the Transcaucasian Corps.

Beginning in the 1830s, Molokans began resettling in the territory of current Azerbaijan, Georgia, Armenia, and Turkey. Initially the Karabakh province was the place of settlement of Russian sectarians in the Caucasus, where Dukhobors from the Don and Molokans from the Tambov Province were exiled. After 1833, the Minister of Internal Affairs permitted settlement in other regions of Transcaucasia (Dolzhenko 1985:23). The state sought, on the one hand, to isolate the Orthodox population from the “sectarian contagion” and, on the other hand, to repopulate the new outskirts of the empire (Breyfogle 2005). In particular, the introduction of relaxing laws concerning immigrants and the religious freedom led many sectarians to come there voluntarily (Dolzhenko 1985:21-24). Since the annexation of new territories in the Far East in the second half of the nineteenth century, the government started resettling many Molokans to the Amur Region (Buyanov 2013).

In the mid-1830s, prophets appeared in the Molokan villages of Samara, Saratov, Astrakhan, and Taurida Provinces, proclaiming the imminent end of the world and the advent of the millennial kingdom of the righteous. Lukyan Sokolov of Tambov announced doomsday in 1836, prophesying the need to move to Ararat, where it is possible to build a New Jerusalem among the chosen people. In Taurida and Saratov Provinces, Fyodor Bulgakov (David Evseevich) preached about the millennial kingdom of the righteous. These prophecies led to mass migrations of Molokans to Transcaucasia (Klibanov 1965:130-31).

In the Volga region, Mikhail Popov and Evstigney Galyaev composed the Charter of the Common Trust and became the founders of the Communalist (obshchie) Molokans. The work proposed a blueprint for organizing life based on the community of property and the obligation to work. They reported on the nearness of doomsday, anticipated a millennial kingdom, and called for purification from filth (Klibanov 1965:136-37). In the 1940s, they were exiled to Transcaucasia.

By the mid-19th century, under the influence of another influential prophet, Maksim Gavrilovich Rudometkin, spiritual Christians-Jumpers (pryguny) stood out in the Caucasus. They were called so for “walking in the spirit,” which accompanied ecstatic bouncing during prayer. They expected the millennial kingdom to come soon. Rudometkin declared himself a spiritual king (vozhd’ dukhovnogo naroda) and crowned himself, forbidding his followers to submit to other authorities. The Jumpers were notable for their special strictness of morals, zeal in prayer and fasting, and stricter prohibitions. Uttered prophecies, speaking in tongues, and leaping were considered manifestations of the action of the holy spirit in man (Klibanov 1965:135). Rudometkin broke with other Molokans by rejecting the Christian holidays that they shared with the Russian Orthodox Church, instead insisting that his followers observe the Old Testament feasts, including Passover, Pentecost, Trumpets (Pamyat’ Trub), Judgement Day, and Tabernacles (Kuschi) (Clay 2012).

In the late 1860s, German Baptists began attracting many Molokan converts to their faith. In particular, the first Russian convert to the Baptist faith was the Molokan preceptor Nikita Isaevich Voronin. One of the founders of the Baptist Union in 1884, Dei Mazaev, was from a wealthy Molokan family in Crimea (Clay 2012).

On April 17, 1905, Tsar Nicholas II issued a decree of religious liberty. Molokans could legally publish their journals, hold congresses, develop national denominational structures, and create organizations.

In 1905, an All-Russian Congress of Molokans took place in Vorontsovka of Tiflis Province, devoted to the centennial anniversary of religious freedom for Molokans in Russia. One of the leaders of the movement, Nikolai Kudinov, proposed unifying the Molokan movement: establishing rituals and dogmatics common to all Molokans, publishing a catechism of Molokan teaching and a “spiritual and moral magazine,” streamlining the election of hierarchs, and convening annual congresses of Molokans (Klibanov 1965:179). His initiatives, however, were not very successful.

The question of Russian statistics in the pre-revolutionary years is difficult to answer. In 1913, Nikolay Kudinov wrote that there were over 1,000,000 Molokans in Russia. According to official statistics, there were up to 200,000 Molokans of various persuasions in the first decade of the twentieth century. Alexander Klibanov states that these figures are probably understated but closer to reality than Molokan data (Klibanov 1965:181). Most Russian Molokans then lived in Transcaucasia (including Kars, which since 1918 was part of Turkey) and the North Caucasus.

Referring to the prophecies, the Jumpers, beginning in the 1900s, sought permission to leave the country. During 1901–1911 over 3,500 Jumpers from the Kars Province, Erivan Province, and Transcaspian Province emigrated to California (Klibanov 1965:145). The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 hastened the exodus of the Molokan Jumpers from Transcaucasia (Clay 2011:124). By 1911, the emigrated Jumpers had settled in Los Angeles, while Constant Molokans chose San Francisco. Most Molokans remained in the Russian Empire (Hardwick 1993:353). By the mid-1920s, small groups of Molokans scattered across the American West in search of a suitable place for a rural community. Some went to Hawaii; the others tried farming near Glendale, Arizona. In 1906, a large group of Molokans bought land in Mexico, Baja California. They established the Guadalupe Russian Colony, and about 120 families lived there by 1915 (Mohoff 1993:62). Other American Molokan families went to the Central Valley in California and Oregon (Hardwick 1993:135-36).

By 1937, the Mexican Molokans were faced with a cultural and economic crisis and started relocating to the U.S. (Mohoff 1993:60-61). Later, the Molokans who remained in Mexico had recurring problems with the locals who tried to seize their land. In October 1962, the last Russians left the Valley. The village was renamed Francisco Zarco (Mohoff 1993:187). By the 1930s, over 6,000 Molokans lived in Los Angeles (Nitoburg 2005:306). In 1940, there were already 13,500 Molokans in California (Nitoburg 2005:310). In the 1950s, about 700 Molokans migrated from Iran to California; they had managed to move from Armenia to Iran during the collectivization period in the 1930s (Nitoburg 2005:312).

At the beginning of the 1920s, amidst the persecution of the Orthodox clergy, non-traditional religious groups experienced an upsurge. On October 5, 1921, the People’s Commissariat for Agriculture published a proclamation To the sectarians and Old Believers living in Russia and abroad. According to the proclamation, they could “find themselves quite at ease and know firmly that for their teachings nobody ever will be persecuted” (Batchenko 2019:191). In 1921, the Molokans reconstituted the Union of Spiritual Christians Molokans. In 1924, they were permitted to hold the Second All-Union Congress of Molokans in Samara, where Nikolay Kudinov became the chairman of the Central Council. In 1925, a monthly magazine, Vestnik of Spiritual Christians Molokans, began publication (Batchenko 2019:193). The authorities saw the Spiritual Christians as their allies and allowed them to settle on free land and form collective farms. As a result, at the Third All-Union Congress of the Molokans in 1926, the goals of the Soviet state were recognized as “quite consistent with the worldview of spiritual Christianity” (Danilova 2018:68).

In 1926, state policy toward sectarians shifted, and they were identified as the most dangerous religious associations because of the growth in the number of their communities. In 1927, a secret circular was issued restricting sectarian activity. Printed publications and houses of worship were closed, Molokan conventions did not convene, and the leadership of the Union was repressed (Batchenko 2019:195-96). The 1929 decree forbade sectarians to create their own economic and production associations and cooperatives (Danilova 2018:77).

The Soviet policy of religious persecution and prohibition led to a gradual decline in the number of Molokans. The Molokan Jumpers communities continued to operate, refusing to register, but under the scrutiny of the security authorities. At the end of 1961, Molokans from Turkey (more than 1,500 people) returned to the Soviet Union and were settled in the Stavropol and Astrakhan Regions (Samarina 2004:111-12).

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, for economic, political, and ethnic reasons, most of the Molokans of Transcaucasia left for Russia, the United States, and other countries. The only remaining villages in Armenia and Azerbaijan compactly settled and attempted to preserve their traditional ways of life, while almost all the residents of Georgia have left. In particular, in Yerevan, there are five Jumper communities and one community of Constant Molokans. In Georgia and Azerbaijan, one can find only a small number of Constant Molokans. Molokan communities exist today in Australia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Russia, the United States, and Ukraine.

In June 1991, a Molokan Congress was held in Moscow. The congress proclaimed the revival of the Union of Spiritual Christians-Molokans, elected a Council of 9 members, and adopted the Union’s Charter. The printed organ is the magazine Spiritual Christian. The Union was supposed to link disparate communities, but in reality, only Constant Molokans became members (Inikova 1998:88-89). In the same year the Committee for Assistance to Resettled Molokans was established. In 1994, the Union of Spiritual Christian Molokan Communities of Russia was created and registered by the Ministry of Justice. The center is in the village of Kochubeevskoe, Stavropol Region. In the Russian Federation eighteen Molokan organizations are registered (Rossiya v tsifrakh 2019:179). Molokans live mainly in the southern part of the country: Krasnodar, Stavropol, and Rostov Regions.

In the 1990 Directory, more than four thousand people in the American West continue to identify as Molokans. Hardwick suggests that there are even more because Berokoff in the 1960s numbered between 15,000 and 20,000 Molokans (Hardwick 1993: 137-139).

The migration of Molokans from the United States to Australia began in 1964 after the prophecy of salvation spread there (Dunn 1978:354). In the 2000s, there were approximately 125 families in South and Western Australia (Slivkoff 2006:19).

In 2005, the World Congress of Spiritual Christians of Molokans took place in the village of Kochubeevskoe, Stavropol Region. It was “dedicated to the 200th anniversary of granting the Molokans freedom of religion.” Molokans from different regions of Russia, as well as from Australia, Canada, and the United States, took part. They discussed the questions of educating young people in the traditions of Molokan teaching and the allocation of land for building prayer houses and a cultural center. However, the Molokan community could not agree on the allotment of land with the administration, and the building for the meeting in Moscow still has not been built.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Like many other Russian sectarian groups, the Molokans did not develop a unified doctrinal system. It has been characterized by decentralization and rejection of hierarchy. Molokan beliefs divided into groups. The only two remaining branches are the “Constant” (postoyannye) and the “Jumpers” (pryguny), or simply Spiritual Molokans.

All currents of Molokanism have been based on their conception of God and the Bible, although the theological views were not well developed and prescribed. For Molokans, the Bible has authority as the only God-inspired source of faith, and knowledge of Scripture serves as evidence of the religious perfection of believers (Klibanov 1965:123). The notion of the Trinity varies. In the ritual book of the first half of the nineteenth century, God is understood as “Spirit in three persons.” In contrast the Exposition of the Uklein Doctrine states that “God the Son and the Holy Spirit, though of one essence with the Father, are not equal to him in a deity” (Buyanov 2013:17).

According to Molokan teachings, no one should understand the Bible literally and formally follow its prescriptions. It is more proper to interpret it allegorically and to have many interpretations of the passages (Bonch-Bruevich 1973:248-49). In addition to the Bible, Molokans have many handwritten Charters and Rites. The Jumpers also use a book, Spirit and Life. The Book of Sun, that was compiled from the writings of Molokan prophets, the most famous of whom is Maxim Gavrilovich Rudometkin. He is considered “the King of Spirits and the leader of the Zion people,” and for extreme Maximist Jumpers, even the incarnation of the Holy Spirit on earth (Nikitina 2013:164). The book Spirit and Life was written over several decades in the nineteenth century and was first published in America in 1915. The second edition was published in Los Angeles in 1928 and was repeatedly reprinted (Nikitina 1998:222). It outlines the history and main points of the Jumpers’ teaching.

All Molokans do not recognize church symbolism: the priesthood, sacred tradition, icons and saints, temples, and liturgical luxuries. They refuse to revere the cross or to make the sign of the cross. They reject all Orthodox sacraments, interpreting them as spiritual acts. They teach that “the worship of God must be in the spirit of truth.” In particular, the Orthodox Eucharist is mere bread and wine and offers no salvation. They believe in Holy Spirit baptism, not water baptism (Clay 2012).

The Molokan Jumpers anticipate the second coming of Christ and the coming of the millennial kingdom. They have developed the concept of the pokhod (hike). “The pokhod is an exodus from places where faith and way of life are under threat of destruction. It is a movement to where there will be a new heaven and a new earth, where the seventh day of creation will be realized” and the millennial kingdom of the elected believers will come. The idea of the pokhod is closely linked with the institution of prophecy: the Holy Spirit shows where and when to move (Nikitina 1998:228-29).

Molokans emphasize “good works” in matters of salvation. Diligence, discipline, persistence in achieving their goal, and practicality are characteristics of Molokan work ethics. Molokans believe that personal salvation directly depends on honesty and conscientious work.

Constant Molokans celebrate the major Orthodox holidays, while Jumpers have only five Old Testament holidays: the Jewish calendar Passover and Pentecost, the Remembrance of the Trumpets (Pamyat’ trub), Judgment Day, and Tabernacles.

Molokans adhere to some Old Testament food prohibitions, among which the most enduring is the injunction not to eat pork. One of the key Molokan slogans is “an icon is not God; pork is not meat.” They also do not eat hare meat, fish without scales, hybrids of fruits and vegetables. Sometimes they may not eat meat cut by others; they try to buy meat only from other believers (Dolzhenko 1992:23). They have a ban on smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The spiritual center of the Molokans is the meeting of believers (sobranie). In their ritual cult, Molokans tried to imitate the apostolic church: they reject censers, lamps, candles, and temples but allow liturgical meetings with the reading of Scripture and the singing of psalms (Buyanov 2013:18). Most  current communities have their own prayer houses, or they gather at the home of one of the believers. In a worship house, [Image at right] there is a table on the right side of the door, covered with a white tablecloth, with the Old and New Testaments; Jumpers also have the Book of Spirit and Life. There are benches covered with rugs and embroidered towels on the walls. People are seated according to seniority. Meetings are usually held on Sundays. The Armenian Jumpers attend at least three times a week: Saturday evening, Saturday morning, and Sunday evening.

current communities have their own prayer houses, or they gather at the home of one of the believers. In a worship house, [Image at right] there is a table on the right side of the door, covered with a white tablecloth, with the Old and New Testaments; Jumpers also have the Book of Spirit and Life. There are benches covered with rugs and embroidered towels on the walls. People are seated according to seniority. Meetings are usually held on Sundays. The Armenian Jumpers attend at least three times a week: Saturday evening, Saturday morning, and Sunday evening.

The prayer meeting consists of readings and explanations of texts from the Bible, followed periodically by psalms. Psalms are texts for singing in worship from the various books of the Bible. The singers uniquely sing them, after the narrator reads each line (Nikitina 2013:43). Each syllable is sung for a very long time and drawn out. The Jumpers also use texts from the Songbook of Zion (Sionskiy pesennik), first published in 1930. The authors of the songs have varied and include the chief Molokan prophet, Maxim Rudometkin. Now regularly reprinted, supplemented, and used during prayer meetings, the collection includes pre-revolutionary hymns and Protestant songs. The motifs of the spiritual songs are the singing of the power of the almighty God, uncomplaining obedience to a harsh fate, the struggle between good and evil, etc. The Molokans sing spiritual songs during family rites, festive celebrations, and gatherings (Samarina 2004:138-39).

After psalms, the presbyter and elders hold conversations (besedy), which are essentially sermons. A characteristic feature of the Jumpers is the presence of prophets within the meeting. The community can have one prophet or even several. Sometimes the prophecies can come down on any believer present at the meeting. In the gatherings of the Jumpers, the psalms are more rhythmic. Some believers, falling into religious ecstasy, come into contact with the holy spirit and try to convey the “thoughts of God” to all believers (Samarina 2004:141). The service ends with communal prayer and kneeling. In some communities, the “holy kiss” is also preserved (at the end of the meeting, all praying believers approach several elders and kiss them).

The Molokans perform the rites of passage in their meetings, usually on weekends and holidays. These rites include christenings (kstiny), weddings, funerals, and memorial services. The elders read certain psalms and chapters from the Bible. All religious festivals and rituals accompany a joint meal (delo) that is a sacrifice dedicated to some rite of the life cycle, feast, or event.

Molokan christening (kstiny) is very simple, spiritual act. Usually, it takes place after the traditional Sunday gatherings. The parents bring their child to the presbyter to be blessed and recorded in the Book of Life. The presbyter [Image at right] reads prayers over the infant (Dolzhenko 1974:93). The usual meal (delo) then takes place. From this point on, the child is under the blessing of the Lord (Samarina 2004:160).

The marriage ceremony includes a blessing by the parents, a sermon from the presbyter, and the bride and groom’s consent to the audience. Then the presbyter reads the duties of the spouses to each other and ritually passes the bride to the groom. Reading passages from the Bible is interspersed with the singing of psalms and spiritual songs (Dolzhenko 1992:15-16). Marriage for Molokans is considered irrevocable; divorce has remained unacceptable.

The entire community to which the deceased belonged attends a funeral. It takes place on the third or fourth day, and the relatives come out in a circle and ask to pray for the well-being of the deceased in the other world. The presbyter concludes by reciting a prayer. After burial in the cemetery, [Image at right] the relatives invite everyone to remember the departed. A commemoration meeting (pominy) is also held on the fortieth day and the anniversary of the death. At the gathering, relatives ask for forgiveness for their sins and the sins of the dead, and after the worship service, they share a meal (Dolzhenko 1974:94).

On feast days, Molokans hold prayer meetings at which the presbyter and the elders preach sermons on the Gospel themes that form the basis of the feast. The singers perform relevant psalms. The service ends with general prayers (Samarina 2004:142). Unlike the Jews, the Molokans do not celebrate the Sabbath. For them, Sunday is a special day of the week. Like the first Christians, they honor each Sunday as the day of Christ’s Resurrection. On this day, as with the Orthodox, all work is forbidden. In the morning, dressed festively, everyone goes to the meeting (sobranie), then they socialize together (Samarina 2004:143). Usually, they keep fasts on the eve of feasts and in the spring and fall, before the beginning and end of agricultural work. The fast lasts one to three days and consists of total abstinence from food (Dolzhenko 1992:23).

The strictest Jumpers do not take pictures, do not watch TV, and do not celebrate birthdays or secular holidays. Religious doctrine forbids all entertainment and idleness, including dancing, playing musical instruments, and playing games. They celebrate religious holidays only in the meetings (sobranie) by reading the Bible, talking about divine matters, and singing psalms and songs.

One of the outward signs of belonging to the Molokan faith is their clothing. Many men wear beards, some wear kosovorotki (a shirt with skewed collar) and kartuz (peaked cap), and in meetings they wear belts with tassels. The women wear long skirts, long-sleeved blouses and shawls, and aprons for meetings. The Molokans have preserved the custom of bowing and kissing each other upon meeting.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Spiritual Christian Molokans organize into congregations headed by presbyters. The presbyter is usually an older Molokan who knows the Scriptures and has earned a good reputation among the believers. Formally he is not considered superior or more important than the other members, but his status allows him to give advice, guidance, and counsel to other believers. The presbyter is chosen for life by the community members or by the spirit through the prophet (Dolzhenko 2004:88). Together with his liturgical duties, he takes care of the congregational needs. He is not entitled to receive money for his work.

The helper of the presbyter and the elders sit together with the presbyter at the head of the table. Nearby are the singers, usually young people, and the skazateli, middle-aged men who call out scriptural passages during the  service. The most honorable members of the congregation are seated closer to the front corner. [Image at right] Prophets play a meaningful role with the Jumpers, and there are both men and women among them. They are ordinary believers upon whom the Holy Spirit descends, conveying a message from God to the congregation or foretelling events. When the prophet speaks in the spirit, the Lord speaks through their mouths (Dolzhenko 1992:9). Each congregation may have different numbers of prophets, ranging from no prophets at all to a few. The besedniki, experts in the Bible who can interpret the Scripture passages, have great authority. Singers are revered in the community as well. All these functions have not been hereditary, they have been self-taught or self-worth, and as a rule, only men have performed them.

service. The most honorable members of the congregation are seated closer to the front corner. [Image at right] Prophets play a meaningful role with the Jumpers, and there are both men and women among them. They are ordinary believers upon whom the Holy Spirit descends, conveying a message from God to the congregation or foretelling events. When the prophet speaks in the spirit, the Lord speaks through their mouths (Dolzhenko 1992:9). Each congregation may have different numbers of prophets, ranging from no prophets at all to a few. The besedniki, experts in the Bible who can interpret the Scripture passages, have great authority. Singers are revered in the community as well. All these functions have not been hereditary, they have been self-taught or self-worth, and as a rule, only men have performed them.

At various times, the Molokans (primarily Constant) have tried to create unifying institutions and developed unified liturgical rites. For example, in the early twentieth century the Molokan preacher Nikolay Kudinov attempted to centralize the movement and create “progressive Molokanism” (Buyanov 2013:300). Later in 1923, he organized the All-Russian Union of Religious Communities of Spiritual Christians Molokans (which existed until 1929) where he was the chairman of the council (Buyanov 2013:309). A Molokan magazine, Vestnik of Spiritual Christians Molokans, beginning publication in 1925, constantly promoted the idea of strengthening the Molokan organization. In 1991, the Union of Spiritual Christian Molokan Communities was recreated, which included only a portion of the Constant Molokan communities (Inikova 1998:88-89). All attempts at centralization have not been very successful. As they survived for only a short time and always combined only one part of the Molokans.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

The main challenge for researchers on the Molokan tradition is that there is no single set of Molokan teachings. At different times there have been leaders who have formed new interpretations of the old doctrine (or doctrines), creating their own communities of followers. Accordingly, theological interpretations also varied.

Each community has established its own rules and order of service, interpreted biblical texts in its own way, and, on that basis, observed food, marriage, occupational, and civil prohibitions to varying degrees. Again, intermittent contact between communities in different countries has led to significant differences in ritual and everyday behavior. For example, the Molokans in Armenia know little about their Georgian co-religionists. At the same time, after the fall of the Soviet Union, contacts developed between American and post-Soviet Molokans. In particular, American Jumpers have repeatedly provided financial assistance for the construction of worship houses in Armenia and Russia and have also come in search of marriage partners.

The relationship of Molokans with the government has developed differently: in the same period, various branches of Molokanism demonstrated both respectful and extremely critical attitudes toward the authorities. Refusal or consent to serve in the army, register communities, and participate in secular events varied in different periods of Molokanism’s existence. As a rule, the most loyal to secular authority were the congregations of the permanent, and the individual communities of jumpers were the most strictly observant and isolated from secular society.

IMAGES

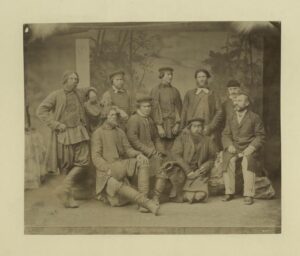

Image #1: A group of Molokan men.

Image #2: A Molokan worship house.

Image #3: A Molokan presbyter.

Image #4: A Molokan cemetery.

Image #5: A Molokan holy corner.

REFERENCES

Batchenko, Viktoriya. 2019. “Vserossiyskie i vsesoyuznye s’ezdy dukhovnykh khristian-molokan v 1921–1929 gody.” Rossiyskaya istoriya 1:191-96.

Bonch-Bruevich, Vladimir. 1973. Sektantstvo i staroobryadchestvo v pervoy polovine XIX veka. Pp. 214-63 in V. D. Bonch-Bruevich. Izbrannye ateisticheskie proizvedeniya. Moscow: Mysl’.

Breyfogle, Nicholas. 2005. Heretics and Colonizers: Forging Russia’s Empire in the South Caucasus. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Buyanov, Evgeniy. 2013. Dukhovnye khristiane molokane v Amurskoy oblasti vo vtoroy polovine XIX – pervoy treti XX veka. Blagoveshchensk: Amurskiy gosudarstvennyi universitet.

Clay, Eugene. 2012. Russian Molokans: Their Roots and Current Status. The East-West Church & Ministry Report, vol. 20, no. 2. https://www.eastwestreport.org/43-english/e-20-2/340-russian-molokans-their-roots-and-current-status

Clay, Eugene. 2011. “The Woman Clothed in the Sun: Pacifism and Apocalyptic Discourse among Russian Spiritual Christian MolokanJumpers.” Church History 80:10938.

Danilova, Elena. 2018. “Vyrazhaem polnuyu gotovnost’ pomogat’ Sovetskoy vlasti…» Nedolgiy opyt integratsii dukhovnykh khristian v sovetskuyu ekonomiku 1920-kh godov.” Gosudarstvo, religiya, tserkov’ v Rossii i za rubezhom 3:60–80.

Dolzhenko, Irina. 2004. “Sovremennoe molokanstvo Armenii: struktura religioznoy organizatsii.” Pp. 88-91 in Nauchnye Trudy Tsentra armenovedcheskikh issledovaniy Shiraka.” 7. Gyumri.

Dolzhenko, Irina. 1992. Religioznyy i kul’turno-bytovoy uklad russkikh krest’yan-sektantov Vostochnoy Armenii (XIX — nachalo XX veka). Pp. 7-25 in Dukhobortsy i molokane v Zakavkaz’ye. Moscow: IEA RAN.

Dolzhenko, Irina. 1985. Khozyaystvennyy i obshchestvennyy byt russkikh krest’yan Vostochnoy Armenii (konets XIX — nachala XX vekov). Yerevan: Izdatel’stvo Akademii Nauk ArmSSR.

Dolzhenko, Irina. 1974. “Semeynaya obryadnost’ russkogo naseleniya Armenii.” Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutʻyunneri 7:87-96.

Dunn, Ethel and Stephen Dunn. 1978. “The Molokans in America.” Dialectical Anthropology 3:349-60.

Hardwick, Susan. 1993. “Religion and Migration: The Molokan Experience.” Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers 55:127-41.

Inikova, Svetlana. 1998. “Problemy etnokonfessional’nykh grupp dukhobortsev i molokan.” Pp. 84-103 in Faktor etnokonfessional’noy samobytnosti v postsovetskom obshchestve, edited by M.B. Olkott and A.V. Malashenko. Moscow: Moskovskiy tsentr Karnegi.

Klibanov, Alexander. 1965. Istoriya religioznogo sektantstva v Rossii (60-e gody XIX veka – 1917 god). Moscow: Nauka.

Mohoff, George. 1993. The Russian Colony of Guadalupe Molokans in Mexico. U.SA. [s.n.].

Nikitina, Serafima. 1998. “Sotvorenie mira i kontsept iskhoda/pokhoda v kul’ture molokan-prygunov.” Pp. 220-230 in Ot bytiya k iskhodu. Otrazhenie bibleyskikh syuzhetov v slavyanskoy i evreyskoy narodnoy kul’ture. Sbornik statey. Volume 2. Moscow: GEOS.

Nikitina, Serafima. 2013. Konfessional’nye kul’tury v ikh territorial’nykh variantakh (problemy sinkhronnogo opisaniia). Moscow: Institut naslediya D.S. Likhacheva.

Nitoburg, Eduard. 2005. Russkie v SSHA: istoriya i sud’by, 1870-1970: etno-istoricheskiy ocherk. Moscow: Nauka.

Rossiya v tsifrakh. 2019. Moscow: Rosstat.

Samarina, Olga. 2004. Obshchiny molokan na Kavkaze: istoriya, kul’tura, byt, khozyaystvennaya deyatel’nost’. Dissertatsiya na soiskaniye uchenoy stepeni kandidata istoricheskikh nauk. Stavropol’.

Slivkoff, Paulina. 2006. The Formation and Contestation of Molokan Identities and Communities: The Australian Experience. MA Thesis, Anthropology and Sociology, University of Western Australia.

Publication Date:

30 October 2022