STATE MUSEUM OF THE HISTORY OF RELIGION TIMELINE:

1918: The Decree on the Separation of the Church from the State and the School from the Church was issued.

1922: The Church Valuables Campaign took place.

1925: The League of the Godless (after 1929 the League of the Militant Godless) was founded.

1929: The Law on Religious Associations was passed.

1932: The Museum of the History of Religion of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR was founded in Leningrad in the former Kazan Cathedral, with Vladimir Germanovich Bogoraz as Director.

1937: Iurii Pavlovich Frantsev was appointed museum director.

1946: Vladimir Dmitrievich Bonch-Bruevich was appointed as museum director.

1951: The Manuscript Division (later Archive) opened.

1954: The museum was renamed The Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism

1956: Sergei Ivanovich Kovalev was appointed museum Director.

1959-1964: Nikita Khrushchev organized antireligious campaigns.

1961: The museum was transferred from the Academy of Sciences to the Ministry of Culture of the USSR.

1961: Nikolai Petrovich Krasikov was appointed museum Director.

1968: Vladislav Nikolaevich Sherdakov was appointed museum Director.

1977: Iakov Ia. Kozhurin was appointed museum Director.

1985-1986: Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and launched glasnost’ and perestroika policies.

1987: Stanislav Kuchinskii was appointed museum Director.

1988: The Millenium of the Christianization of Rus’ was celebrated with official permission.

1990: The museum was renamed the State Museum of the History of Religion.

1991: A joint use agreement was reached with Russian Orthodox Church for use of the Kazan Cathedral; regular religious services resumed.

1991 (December 25): The USSR collapsed.

2001: A new building and permanent exhibit were opened.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The State Museum of the History of Religion (Gosudarstvennyi muzei istorii religii – GMIR) is one of very few museums in the world devoted to the interdisciplinary study of religion as a cultural-historical phenomenon. Its holdings include approximately 200,000 items from all over the world and across time. In addition, GMIR is home to a library of 192,000 items, including scholarly books on all religions and topics in the history of religion and atheism, as well as major collections of religious books and books on religious themes published from the Seventeenth to the Twenty-First century. Finally, its archive contains 25,000 files and items, including the materials of state and public organizations connected to religion, numerous personal fonds, archival collections of various religious groups (especially smaller Russian Christian groups, such as the Dukhobors, Baptists, Old Believers, Skoptsy and others), and a collection of manuscript books in Church Slavonic, Latin, Polish, and Arabic (GMIR website 2016).

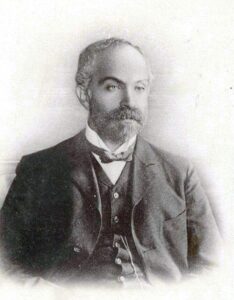

The museum was founded in 1932 as the Museum of the History of Religion of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Its founder and first director was Vladimir Germanovich Bogoraz (pseudonym N. A. Tan) (1865-1936). [Image at right] Bogoraz was an internationally renowned ethnographer and linguist. He specialized in the indigenous peoples of Siberia, in particular the Chukchi, having developed his expertise during a decade of exile in northeastern Siberia in the 1890s as a revolutionary. Since 1918, he had worked at the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography of the Academy of Sciences in Leningrad and had played a major role in the flowering of Soviet ethnography in the 1920s, as well as founding the Institute of the Peoples of the North in 1930 (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:23-24).

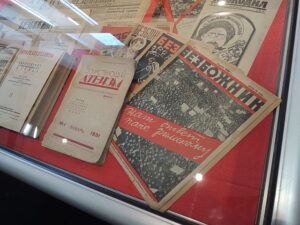

Not long after coming to power in late 1917, the Bolsheviks launched a multi-pronged campaign against religion. As Marxists, they regarded religion as a remnant of capitalist power structures and sought to inculcate a materialist world view in the population. On the one hand, they attacked religious institutions: the January 1918 Decree on the Separation of Church and State nationalized religious property and secularized state life and education, and the 1918 Constitution disenfranchised members of the clergy. (Thereafter, local groups of lay believers, rather than denominational institutions, could lease buildings and ritual objects for their use). In the face of famine, in 1922 the regime inaugurated a confrontational policy of seizing church valuables, ostensibly to raise funds to feed the hungry. Meanwhile, the Soviet secret police worked to break religious organizations from within and to force religious leaders to declare loyalty to the new regime. The 1929 Law on Religious Associations forbade religious organizations to engage in any activity besides the strictly liturgical, including the teaching of religion to children. That same year, the Bolsheviks removed the right to “religious propaganda” from the Soviet constitution. On the other hand, the Bolsheviks sought to foster a cultural revolution that would produce a new Soviet person with a Communist, scientific, and  secular world view. In late 1922, a popular weekly newspaper, The Godless (Bezbozhnik), was launched and the League of the Godless was founded in 1925 to co-ordinate antireligious propaganda; from 1926 to 1941, it also published a journal of antireligious methods, The Antireligious Activist (Antireligioznik). [Image at right] In 1929, the League renamed itself the League of the Militant Godless.

secular world view. In late 1922, a popular weekly newspaper, The Godless (Bezbozhnik), was launched and the League of the Godless was founded in 1925 to co-ordinate antireligious propaganda; from 1926 to 1941, it also published a journal of antireligious methods, The Antireligious Activist (Antireligioznik). [Image at right] In 1929, the League renamed itself the League of the Militant Godless.

These policies had important implications for scholarship on religion in the USSR. The antireligious campaigns provided both the justification and the framework for religious studies. Moreover, the secularization of religious buildings and the seizure of church valuables brought substantial collections into state hands. In the years after the revolution, the Academy of Sciences of the USSR sought to preserve the national cultural and religious heritage amidst the process of nationalizing and repurposing religious buildings. Its library and museums acquired religious objects, manuscripts, and artwork, as well as the archives and libraries of various monasteries and religious academies (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:21-23).

The prehistory of the GMIR began in 1923 when Bogoraz, together with L. Ia. Shternberg, his fellow ethnographer at the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography and the first scholar to teach Religious Studies at St. Petersburg University in 1907, proposed to curate an antireligious exhibit based on the collections of the Museum (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:13-14, 24). The exhibition opened in April 1930 at the famous Hermitage Museum (in the former Winter Palace) in honour of the fifth anniversary of the founding of the League of the Godless. Bogoraz and his colleagues aimed to provide a comparative and evolutionary account of the development of religion as a phenomenon in human history. Many of the artifacts on display at this very popular exhibit eventually made their way into the collections of the GMIR (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:24-26).

In September 1930, the Presidium of the Academy of Sciences considered an appeal from the League of the Godless to transform the exhibit into a permanent “Antireligious Museum of the Academy of Sciences.” This coincided with the ambitions of Bogoraz, Shternberg (before his death in 1927), and the active community of scholars of religion in Leningrad at the time. In October 1931, the Presidium approved the founding of a “Museum of the History of Religion” and appointed Bogoraz as its director. The Museum opened its doors a year later, in November 1932 in the former Kazan Cathedral (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:26-27). The Kazan Cathedral, located on Nevskii Prospect (the great avenue of downtown Leningrad) had been closed a year earlier by the Leningrad Party and city authorities, who accused the impoverished congregation of inadequately maintaining this important historic site.

The GMIR was founded amidst an antireligious museum building boom, spurred by the League of the Militant Godless in the late 1920s and early 1930s. This was the period when Joseph Stalin ascended to the leadership of the Communist Party and launched the First Five-Year Plan to rapidly industrialize the country and collectivize its agriculture. The First Five-Year Plan was accompanied by a militant Cultural Revolution, which sought once and for all to build a proletarian, socialist, and antireligious culture. Young activists in the League threw themselves into this project and hundreds of museums, big and small, were established across the country in this period. The most prominent included the Central Antireligious Museum in the former Strastnoi Monastery in Moscow (1928) and the State Antireligious Museum in St. Isaac’s Cathedral in Leningrad (complete with a Foucault pendulum installed in 1932, which remained there through the early 1990s). By the late 1930s, the League ran out of steam and most of these museums were closed. However, the GMIR avoided this fate and, indeed, acquired many of the collections of Moscow’s Central Antireligious Museum after its permanent closure in 1946. In 2022, it celebrated its ninetieth anniversary.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Throughout its history, the Museum’s work has been shaped by the changing ideology and policy with respect to religion of the Soviet and later Russian Federation governments. As Marxists, the Bolsheviks regarded religion as part of the ideological superstructure that maintained oppressive power and unjust economic relations in societies. It was the “opiate of the people,” diverting individuals from seeing their true interests, and the former state church, the Russian Orthodox Church, had been an instrument of the autocratic political system. They sought to destroy the institutional, symbolic, and social functions of religion, and to spread a rational, materialist world view. The ultimate goal was not merely a secular but an atheist society.

Antireligious policy shifted in intensity and emphasis throughout the Soviet period. In the 1920s, the regime focused on attacking religious institutions, but to a great extent left local religious life alone. The decade from 1929 to 1939, by contrast, saw a full-scale assault on religious practice, with the closing of almost all houses of worship and the mass arrest of clergy. Following the Nazi invasion in 1941, however, Stalin shifted strategies, allowing the Orthodox Church to be reconstituted so that the state could use it to mobilize support for the war effort. Similar deals with other religions followed. The party-state rolled back its antireligious campaigns and formed instead a bureaucratic structure for managing the affairs of the various confessions. Although the party did not renounce atheism as a goal, even after victory in 1945 it did not reinvest either financial or ideological resources in promoting it (Smolkin 2018:46-47, 50-52, 55). However, following Stalin’s death in 1953, atheism returned to the party’s agenda, culminating in a major new wave of antireligious campaigns launched in 1958 under Nikita Khrushchev. The Khrushchev era witnessed renewed state attempts to break religious denominations from within and to close places of worship, but it also saw a new focus on breathing positive content into Soviet atheism, on developing scientific atheism as a scholarly field, and on building institutions to promote atheist world views. The “Knowledge Society” developed a whole program of atheist clubs, exhibits, theatre, lecture series, libraries, films, and the popular magazine Science and Religion (Nauka i religiia); meanwhile, an Institute of Scientific Atheism within the Academy of Social Sciences of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, formed in 1964, co-ordinated all scholarly atheist work in the country and trained professional atheists. After Khrushchev’s forced retirement in 1964, the regime returned to an emphasis on the bureaucratic management of religious life rather than openly aggressive antireligious measures; at the same time, the atheist infrastructure remained in place and continued to work to form a population of convinced atheists (Smolkin 2018:chapters 2-5).

Throughout the Soviet period, the Museum stood on the blurred line between being a scholarly institution and part of the communist regime’s ideological apparatus. Bogoraz aimed to bring together antireligious propaganda and scientific enlightenment in the Museum’s work. Historians Marianna Shakhnovich and Tatiana Chumakova conclusively demonstrate Bogoraz’s successful insistence that the Museum be fundamentally a scholarly research institute dedicated to the study of religion as a complex social and historical phenomenon. The Museum’s Statute, approved by the Academy of Sciences in 1931, thus presented its purpose as the study of religion in historical development, from its emergence up to its current condition. It was this scholarly emphasis that differentiated GMIR from the many antireligious museums of its founding era. Bogoraz and Shternberg had excellent revolutionary credentials but were not Marxists; they and their ethnographic school were committed to deep empirical and comparative study of cultural evolution, and there remained room for such people in the Academy of Sciences, even in 1932. As Shakhnovich and Chumakova point out, however, throughout the Soviet period, much scholarly work, especially on ideologically fraught topics such as religion or contemporary Western art and music, had to be justified and cloaked in Party slogans (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:15, 23; Slezkine 1994:160-63, 248).

An early GMIR poster reveals this combination of the scholarly and the mobilizational: it announced that the new museum’s goal was to “[show] the historical development of religions from the most ancient times to our days, and religious organizations, to [reveal] the class role of religion and religious organizations, the development of antireligious ideas and the mass godless movement” (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:34). In the 1930s and 1940s, the  Museum’s staff produced substantial scholarly publications, organized major expeditions to gather artefacts, and set up permanent exhibits. They also participated in the antireligious education of the population, conducting tours for 70,000 visitors per year, [Image at right] and mounting various temporary exhibitions on explicitly political themes including “Karl Marx as a Militant Atheist,” “The Church in the Service of Autocracy,” religion and Japanese imperialism, religion and Spanish fascism, as well as seasonal anti-Christmas and anti-Easter displays (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:136-37, 417). Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich, director from 1946-1955, wrote in 1949 that citations from “Lenin, as well as Stalin, Marx and Engels should everywhere accompany the visitor” (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:79).

Museum’s staff produced substantial scholarly publications, organized major expeditions to gather artefacts, and set up permanent exhibits. They also participated in the antireligious education of the population, conducting tours for 70,000 visitors per year, [Image at right] and mounting various temporary exhibitions on explicitly political themes including “Karl Marx as a Militant Atheist,” “The Church in the Service of Autocracy,” religion and Japanese imperialism, religion and Spanish fascism, as well as seasonal anti-Christmas and anti-Easter displays (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:136-37, 417). Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich, director from 1946-1955, wrote in 1949 that citations from “Lenin, as well as Stalin, Marx and Engels should everywhere accompany the visitor” (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:79).

Bonch-Bruevich, a close associate of Lenin, was both a scholar of sectarian religious movements and a fervent atheist and Party stalwart. He oversaw vast expansion in the scholarly activity of the museum and a renewal of its exhibits, all the while working to restore atheism to the Party’s political priorities and to build it into the Academy of Sciences’ scholarly agenda. In 1954, the Museum of the History of Religion became the Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism, and in 1955 the Academy of Sciences adopted measures to organize “scholarly-atheist propaganda” in its various institutions (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:77-78; Smolkin 2018:63-65). Between 1954 and 1956, the museum hosted a million visitors and curators gave 40,000 tours; in these years it also published a series of brochures to popularize scholarly research on antireligious topics (GMIR website 2016; Muzei istorii religii i ateizma 1981).

From the 1960s to the 1980s, the Museum played a central role in the Soviet regime’s atheist propaganda program. Under pressure from the Leningrad provincial Party leadership, the Museum partly transformed itself into a “scholarly-methodological centre.” Curators began to organize symposia and lectures for antireligious activists and to travel around the country with exhibitions and to give lectures (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:419). From 1978 through 1989, the Museum published an annual series of books on museums and their function in atheist propaganda, as well as collected volumes on topics such as “Social-Philosophical Aspects of the Criticism of Religion,” “Current Problems in the Study of Religion and Atheism,” and “Social-Psychological Aspects of the Criticism of Religious Morality.”

The last years of the 1980s and early 1990s, when the Communist Party under the leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev launched the policies of perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost’ (openness), posed a major challenge to the Museum and its mission. The loosening of censorship and political controls had religious effects that the regime had not anticipated: religious groups expanded their public activities, previously repressed denominations emerged from underground, imprisoned prisoners of conscience were released, and the press wrote more freely about history and religion. The key turning point came in 1988, when the Orthodox Church celebrated the 1000th anniversary of the Christianization of Rus’ with the sanction of the state and in the presence of numerous foreign guests. As the state’s relationship with religion was transformed in these years, the atheist propaganda apparatus found itself in a state of crisis. As the head of the scholarly-methodological department at GMIR wrote in 1989, “Our atheism has suffered a defeat similar to that which religion experienced in the period of the October Revolution…” (Filippova 1989:149). Indeed, that same year, the Orthodox Church was permitted to hold a service in Kazan Cathedral for the first time in six decades. In 1990, the words “and Atheism” were dropped from the Museum’s name, and in 1991, the decision was made to return the Kazan Cathedral to the Russian Orthodox Church and to move to a new building on Pochtamtskaia Street. A joint-use agreement was signed and regular religious services resumed.

In the post-Soviet era, and especially as the Museum redeveloped its permanent exhibition after moving in 2000, the antireligious and anticlerical aspects disappeared. The Museum now sought to offer a secular but balanced presentation of religious history and practice, although it preserved its collections of Soviet atheist artifacts and publications. (Kouchinsky 2005:155). Beginning in 2008, staff launched a long-term project titled “The State Museum of the History of Religion as a Space for Dialogue.” The focus was on strengthening a culture of tolerance and understanding within the multiethnic and multiconfessional society of St. Petersburg and the Russian Federation more generally. Through guided tours of the exhibits, but also lectures,  concerts, workshops, and temporary exhibitions, the program aims to foster knowledge about the beliefs and cultural traditions of the many ethnic and religious communities living in St. Petersburg and the Northwest Region. The museum also offers training for school teachers on teaching world religions and children’s tours aimed at helping children understand religion as a phenomenon of human cultures. [Image at right] In 2011, the museum opened a special children’s department, “The Very Beginning,” “dedicated to the religious beliefs of humankind regarding the genesis of the universe” (Teryukova 2012:541-42).

concerts, workshops, and temporary exhibitions, the program aims to foster knowledge about the beliefs and cultural traditions of the many ethnic and religious communities living in St. Petersburg and the Northwest Region. The museum also offers training for school teachers on teaching world religions and children’s tours aimed at helping children understand religion as a phenomenon of human cultures. [Image at right] In 2011, the museum opened a special children’s department, “The Very Beginning,” “dedicated to the religious beliefs of humankind regarding the genesis of the universe” (Teryukova 2012:541-42).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The First All-Russian Museum Congress in 1930, with the slogan “Replace the Museum of Things with the Museum of Ideas,” had called on Soviet museums to shift from a “custodial to an educational role,” one that would “foster understanding and action” (Kelly 2016:123). Indeed, most Soviet antireligious museums were just that: often, they featured relatively few original objects and their displays focused on criticizing religion and contrasting (backward) religious worldviews with modern, progressive science (Polianski 2016:256-60; Teryukova 2014:255; Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:14-15). By contrast, and despite the fact that the Museum of Religion too was certainly intended to play a key role in antireligious propaganda, from its inception the Museum was dedicated to the gathering, study, and display of things and amassed large collections of literary and material religious culture. In addition to the many artifacts, manuscripts, and books acquired from the collections of the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, the State Hermitage, the library of the Academy of Sciences, and the Russian Museum (often due to the nationalization and seizure of religious buildings and valuables), Museum staff in the 1930s organized expeditions all over the Soviet Union to collect materials on the religious life of the national minorities in Buriatiia on the Mongolian border, in Uzbekistan, in the far north, across Siberia, in the Volga region, the Caucasus, and the northwest. They collaborated with N. M. Matorin’s ethnographic research group at Leningrad State University, which conducted expeditions that sought to describe and map “religious syncretism” and everyday religiosity throughout the Russian Republic of the USSR (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:38-39; Teryukova 2020:122). Such expeditions to gather documents and material culture from religious communities have continued up to this day. Under the leadership of Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich in the 1950s, the well-connected director used his influence to acquire substantial archival fonds, including the personal collections of prominent scholars and extensive materials belonging to various religious movements and individuals found in the Ministry of Internal Affairs archives. Many of these had been seized by the political police in the early 1930s if the reader is to judge from official stamps on the materials (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:88-89; personal observations).

In the 1930s, curators laid down the basic principles of the museum’s exhibit: an evolutionary and comparative approach based on a Marxist historical periodization, with religious and anticlerical phenomena for each period presented in parallel. A 1933 report described the following sections: 1) History of the Kazan Cathedral 2) Religion in pre-class society 3) Religion of the feudal East (the centerpiece of which was the Sukhavati Paradise, the only example of a Buddhist paradise sculptural composition to be found in a museum at the time) 4) Religion in feudal society in the West and East (including a display of instruments of torture from the Inquisition) 5) Religion in capitalist society 6) Religion and atheism in the era of imperialism and proletarian revolution, and 7) Religion in the slave-holding societies of Greece and Rome (also including a section on the origins of Christianity). Within these chronological  sections, displays on the history of different religious traditions developed a comparative and functional perspective [Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:136-37, 78, 417]. By the late 1930s, museum curators had begun constructing various dioramas, including of an alchemist’s workshop and of “chambers of the Inquisition.” [Image at right] Mounting these would be an important feature of their work from the 1940s through the 1960s.

sections, displays on the history of different religious traditions developed a comparative and functional perspective [Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:136-37, 78, 417]. By the late 1930s, museum curators had begun constructing various dioramas, including of an alchemist’s workshop and of “chambers of the Inquisition.” [Image at right] Mounting these would be an important feature of their work from the 1940s through the 1960s.

After a period of uncertainty following the Second World War, as the building required major renovations following damage and neglect during the war and the fate of the Museum was being decided, the 1950s was a period of major expansion and development of the museum’s activity. New displays were added, the scholarly library was systematically and greatly expanded, and the archive was founded in 1951. Museum researchers published major monographs on a range of topics in the history of religion and freethinking. From 1957 to 1963, the Yearbook of the Museum of Religion and Atheism published important research by many of the major scholars working in the field in the USSR. The Museum also trained graduate students.

A major reorganization of the exhibit in response to new political challenges and shifts in the Party’s approach saw the development of seven major sections: “Religion in Primitive Soiety,” “Religion and Freethinking in the Ancient World,” “The Origins of Christianity,” “Main Stages in the History of Atheism,” Islam and Freethinking among the Peoples of the East,” “Christian Sectarianism in the USSR,” and “Russian Orthodoxy and Atheism in the USSR.” A 1981 guidebook description of the Islam section provides some insight into the approach adopted: “The section displays materials that familiarize [the viewer] with the history of the emergence of Islam, its beliefs, practices, the development of ideas of freethinking and atheism among the peoples of the East, as well as the evolution of Islam in our country and the process of overcoming it in Soviet society” (Muzei istorii religii i ateizma 1981).

During the 1990s, Museum and Church co-existed in a mutually suspicious manner in the Kazan Cathedral building. The Museum retained its library, archives, storage, and offices in various parts of the building. On the main floor, the sanctuary and part of the nave served as a religious space, cordoned off from the rest of the church, where the museum continued to function. Meanwhile, the Museum awaited the completion of extensive renovations of the building that had been designated for it. The Museum moved in 2000, and in 2001 the new exposition opened to the public.

At present, the Museum’s permanent exhibit includes the following sections: 1. Archaic beliefs and rites, 2. Religions of the Ancient World, 3. Judaism and the Rise of Monotheism, 4. Rise of Christianity, 5. Orthodoxy, 6. Catholicism, 7. Protestantism, 8. Religions of the East, 9. Islam. The history of each group is presented, together with its beliefs and practices. The comparative principle remains strong. [Image at right] For example, the “Archaic Beliefs and Rites” section includes displays on the traditional beliefs and rituals of the peoples of Siberia, North American shamanism, religions of the peoples of west sub-Saharan Africa, the cult of ancestors among the peoples of Melanesia, and “ideas about the soul and the afterlife” (GMIR website 2016).

principle remains strong. [Image at right] For example, the “Archaic Beliefs and Rites” section includes displays on the traditional beliefs and rituals of the peoples of Siberia, North American shamanism, religions of the peoples of west sub-Saharan Africa, the cult of ancestors among the peoples of Melanesia, and “ideas about the soul and the afterlife” (GMIR website 2016).

The Museum continues to develop its library and archive. It also holds major collections of Russian and Western European art, of textiles, items made of precious metals, stamps, rare books, recordings, and photographs. Its staff publishes a series “Works of the GMIR.” The Museum also runs programs to train schoolteachers in the teaching of world religions, various museology- and religion-related professional development mini-courses, and lecture and seminar series, as well as providing mentorship for young religious studies researchers(GMIR website 2016).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The Museum entered a period of turmoil beginning in 1936 with the death of its founding director, Bogoraz (Tan). The following year, the dragnet of Stalin’s great purges scooped up many members of the Leningrad religious studies community, including Matorin. Then in 1941, the Nazi invasion of the USSR brought four years of war and the lengthy siege of Leningrad. The new director, Iurii P. Frantsev, the author of major works on fetishism, nevertheless oversaw an active period of scholarly work. However, from 1942 onwards, he was reassigned to Party work. The Museum remained open during the war, although it suffered damage and was in part used as a storage depot. After victory in 1945, major questions were raised about the future of the museum. The Kazan Cathedral was in dire need of major and expensive renovations; Frantsev was completely preoccupied with his other duties; and the regime’s changed relationship to religious organizations and the re-opening of churches during the war put the Museum’s ideological position in question. Finally, in Moscow, Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich was actively promoting the opening of a central museum of the history of religion in the capital, which would bring together the collections of the former Central Antireligious Museum and the GMIR. In the end, however, Bonch-Bruevich was appointed director of the GMIR in 1946 and the following year the collections of the defunct Moscow museum were sent to Leningrad.

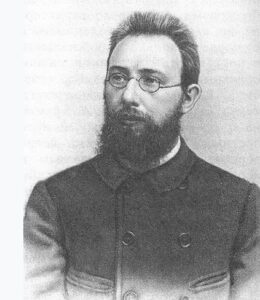

Bonch-Bruevich [Image at right] died in 1955 and his successor was Sergei I. Kovalev, a leading historian of the social history of Ancient Greece and Rome, with a particular interest in the origins of Christianity. His short tenure (he passed away in 1960) saw continual interference by the Party and accusations that the museum was too focused on religion itself, rather than on battling the remnants of religion in contemporary Soviet society. Indeed, a Party commission was formed to investigate the work of the GMIR. Kovalev was unable to mount a successful resistance, and in 1960 a number of long-time researchers left the Museum (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014: 87).

A new era in the life of the GMIR opened in November 1961, when the Museum was transferred from the jurisdiction of the Academy of Sciences to that of the Ministry of Culture. In the context of the intense antireligious campaigns of the era and a series of Party resolutions on the expansion of atheist education and propaganda, the Museum shifted its focus in this direction. Symptomatic of this shift was the expertise of the directors of the Museum from the 1960s to the 1980s. Whereas earlier directors had been historians and ethnographers, now the Museum was led by philosophers, starting with Nikolai P. Krasikov, who served from 1961-1968. His successors, Vladislav N. Sherdakov (1968-1977) and Iakov Ia. Kozhurin (1977-1987), were professional atheists, who had received their doctorates from the Institute of Scientific Atheism of the Academy of Social Sciences of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, an academy established in 1962 for the theoretical training of senior party functionaries. Under their watch, the Museum continued its active collection and research activities but also added its “scholarly-methodological” program devoted to developing materials to support atheist propaganda.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in late 1991, the Museum has been under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation, except for a brief period from 2005-2008 when it was under the Federal Agency on Culture and Cinematography. Stanislav A. Kuchinskii, director from 1987 to 2007, oversaw the complex transition, in times of financial collapse, from Soviet atheistic institution lodged in the Kazan Cathedral to a re-imagined State Museum of the History of Religion in its own specially renovated building.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

As a secular or, (for much of its history) atheist museum devoted to religious history, GMIR has had to tread a careful path. In the late 1950s, for example, the local Party branch launched a review of the Museum’s activities, accusing its staff of excessive attention to religious history (!) and of failing to combat the remnants of religion in Soviet life. It demanded that they re-focus their attention on contemporary materials and set up an exhibit devoted to the overcoming of religion in the USSR. A number of long-time employees resigned in protest (Shakhnovich and Chumakova 2014:87).

This episode hinted at a larger problem that the GMIR (and curators at other Soviet museums lodged in former churches and/or displaying religious artifacts): the cognitive dissonance between the items on display and the secular or antireligious purpose of the exhibit. Museum staff often saw themselves as custodians of church buildings and their contents (for example, the large icon screens that separate the altar from the nave in Orthodox churches), now redefined as “heritage.” Yet, they also found that visitors were more drawn to these colourful, three-dimensional, emotionally charged components than to the formal exhibits. Desacralizing objects and spaces was no easy task: throughout the Soviet period, curators reported that believers would bless themselves and pray before icons on display, for example. Ekaterina Teryukova suggests, indeed, that GMIR staff’s turn to building dioramas in the late 1930s was in part a response to the need to display items in a manner that would convey “the sense, functions, and circumstances in which the object existed“ (Teryukova 2014:257). Indeed, curators themselves were susceptible to the “double-edged” character of “musealized objects of the cult” (in the 1981 words of a senior GMIR researcher): after the collapse of communism, former director Vladislav Sherdakov confessed that he had become a devout Christian many years earlier, the result, he said, of having spent his workdays in the former Kazan Cathedral surrounded by sacred objects and their spiritual influence (Polianski 2016:268-69).

The major task of the post-Soviet period was to redefine GMIR’s relationship with religion: both in terms of rethinking its exhibits and in defining its relationship with the great variety of religious groups in St. Petersburg (and the Russian Federation more generally). Through the permanent exhibition, Museum staff aimed to present the results of scholarly research into the history of religion and religious phenomena in an ideologically neutral fashion. At the same time, they began to establish links with various religious organizations and, in an effort to both build bridges and to provide visitors with more access to the emotionally charged context of religious objects in use, to organize temporary exhibitions jointly with such groups. However, curators also make no promises of immediate display to a religious organization when it donates items to the permanent collection. The Museum thus strives to remain a secular institution devoted to promoting respect and knowledge of various religious traditions (Koutchinsky 2005:156-57).

IMAGES

Image #1: Vladimir G. Bogoraz (Tan), 1865-1936. Accessed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vladimir_Bogoraz#/media/File:%D0%A2%D0%B0%D0%BD_%D0%91%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%B7.jpg p on 20 October 2022.

Image #2: Antireligious Literature 1920s-1930s. Accessed from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/84/Overcoming_%282012_exhibition%2C_Museum_of_modern_history%29_18.jpg/640px-Overcoming_%282012_exhibition%2C_Museum_of_modern_history%29_18.jpg on 20 October 2022.

Image #3: Kazan Cathedral with Stalinist Propaganda, 1930s. Accessed from https://www.sobaka.ru/city/city/81866 on 20 October 2022.

Image #4: Children’s Department Permanent Display, “The Very Beginning.” Accessed from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/49/%D0%9D%D0%B0%D1%87%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%BE_%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%87%D0%B0%D0%BB._%D0%97%D0%B0%D0%BB_1..jpg on 20 October 2022.

Image 5: Shoe Factory Workers’ Excursion to the Museum, 1934. Accessed from https://panevin.ru/calendar/v_kazanskom_sobore_v_leningrade_otkrivaetsya.html on 20 October 2022.

Image 6: Sukhavati Paradise. Accessed fromhttps://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Museum_of_Religion_-_panoramio.jpg

on 20 October 2022.

Image 7: Vladimir D. Bonch-Bruevich (1873-1955). Accessed from https://dic.academic.ru/pictures/enc_biography/m_29066.jpg on 20 October 2022.

REFERENCES

Filippova, F. 1989. “Opyt provedeniia nauchno-prakticheskikh seminarov na baze GMIRiA,” in Problemy religiovedenia i ateizma v muzeiakh. [The Experience of Giving Scholarly-Practical Seminars on the Basis of GMIRA]. In Problems of Religious Studies and and Atheism in Museums. Leningrad: Izdanie GMIRiA.

Kelly, Catriona. 2016. Socialist Churches: Radical Secularization and the Preservation of the Past in Petrograd and Leningrad, 1918-1988. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press.

Koutchinsky, Stanislav. 2005. “St. Peterstburg’s Museum of the History of Religion in the New Millennium” Material Religion 1:154-57.

Muzei istorii religii i ateizma [Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism]. 1981. Leningrad: Lenizdat. Accessed from http://historik.ru/books/item/f00/s00/z0000066/st002.shtml on 20 October 2022.

Polianski, Igor J. 2016. “The Antireligious Museum: Soviet Heterotopia between Transcending and Remembering Religious Heritage.” Pp. 253-73 in Science, Religion and Communism in Cold War Europe, edited by. Paul Betts and Stephen A. Smith. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Shaknovich, Marianna and Tatiana V. Chumakova. 2014. Muzei istorii religii akademii nauk SSSR i rossiiskoe religiovedenia (1932-1961) [The Museum of the History of Religion of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR and Russian Religious Studies]. St. Petersburg: Nauka.

Slezkine, Yuri. 1994. Arctic Mirrors: Russia and the Small Peoples of the North. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Smolkin, Victoria. 2018. A Sacred Place is Never Empty: A History of Soviet Atheism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

State Museum of the History of Religion website. 2016. Accessed from http://gmir.ru/eng/ on 20 October 2022.

Teryukova, Ekaterina. 2020. “G. P. Snesarev as a Collector and Researcher of Central Asian Religious Beliefs (on the Materials of the Collection of the State Museum of the History of Religion, St. Petersburg, Russia).” Religiovedenie [Study of Religion] 2:121-26.

Teryukova, Ekaterina. 2014. “Display of Religious Objects in a Museum Space: Russian Museum Experience in the 1920s and 1930s.” Material Religion 10:255-58.

Teryukova, Ekaterina. 2012. “The State Museum of the History of Religion, St. Petersburg,” Material Religion 8:541-43.

Publication Date:

26 October 2022