TEMPLE OF UNIVERSAL RESCUE TIMELINE

12th century: A temple for the West Liu Village (Xi Liu Cun Si 西刘村寺) was established in what is now Beijing on the site of the later Temple of Universal Rescue.

14th century: The temple was renamed the Bao’en Hongji (报恩洪济) Temple. By the end of the century, it was destroyed during military conflicts in the area.

1466: Assisted by imperial patronage, a temple was rebuilt on the site of the Bao’en Hongji temple’s ruins. The emperor named the temple “Spreading Compassion Temple of Universal Rescue.”

1678: A white marble ordination platform was constructed at the temple.

1912: Sun Yatsen, president of the Republic of China, the country’s first modern state, spoke at the temple.

1931: The temple was destroyed in a fire during a ceremony to protect and safeguard the nation.

1935: The temple was rebuilt in its Ming dynasty style, dating back to the time when it first received imperial patronage.

1953: After falling into police and military uses, and suffering damage from the Chinese Civil War, the temple was reopened under the auspices of the new Communist government and made the headquarters of the Chinese Buddhist Association (Zhongguo Fojiao Xiehui 中国佛教协会; BAC), a government-sanctioned institution. The temple played a key diplomatic function in hosting delegations of visiting Buddhists from other Asian countries. However, it was not reopened to the public.

1966: With the onset of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, the temple ceased to fill any official functions and the BAC was shut down. Charged with destroying all remnants of China’s former “feudal” culture, mobs of Red Guards attacked the temple, but it survived mostly unscathed.

1972: Premier Zhou Enlai ordered the restoration of the temple and rehabilitation of the BAC.

1980: The BAC reconvened at the temple for the first time since the Cultural Revolution, and the temple resumed its religious and official functions.

1980s (Late): Following a gradual lessening of restrictions, the temple opened to the general public during regular daytime hours and devotional ritual activities resumed for the first time in the PRC’s history.

1990s (Mid): Lay Buddhism began to grow and the temple’s outer courtyard, the northernmost of the temple, played host to a vibrant public religious scene, including amateur lay preachers and the sharing and discussion of popular Buddhist literature. The temple monks also established a free, twice-weekly “lecture on the scriptures” (jiangjing ke 讲经课) class to educate laypeople and other interested visitors in Buddhist teachings.

2006: The Temple of Universal Rescue was named as a key site for the protection of Cultural Relics.

2008: The temple donated over RMB¥ 900,000 (U.S. $150,000) to reconstruct an elementary school in Gansu province devastated by the Wenchuan earthquake.

2010s (Mid): The temple authorities took greater control over the public discourses and materials shared in the outer courtyard, which largely ceased to function as a popular religious and civic space.

2018: Extensive renovation work took place at the temple under the framework of Cultural Relics preservation.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Little is known about the original West Liu Village temple that was built on the site in what is now Bejing. The later Temple of Universal Rescue, built in the fifteenth century, was the effort of a group of diligent monks from Shanxi province who had discovered the ruins of the previous temple destroyed nearly one hundred years before and made a vow to rebuild it. Support for this rebuilding came from an imperial palace administrator named Liao Ping (廖屏), who eventually made a successful request to the Ming dynasty emperor Xianzong to give the temple its name.

The temple played an important role in the lineage of the Lü Zong school, one of the eight central schools of Mahayana Buddhism. The Lü Zong school places an emphasis on the following of monastic rules (Vinaya) (Li and Bjork 2020:93). Later on, the temple became an important site for the ordination of new monastics.

The number of resident temple monks has varied throughout history, with periods where monastic residence was completely abandoned following fires or the appropriation of the temple for secular uses. In the post-Cultural Revolution period, between fifteen and twenty-five monastics have generally been in residence in the temple proper, with other senior monastic leaders of the BAC occasionally residing in the northernmost portion of the temple.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The temple’s practitioners follow the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, a prince in the Sákya kingdom in northeast India who likely lived around the fifth to fourth centuries BCE. According to Buddhist scriptures, Siddhartha gave up his status as a prince and would-be king to live a peripatetic life as a renunciant and teacher. His followers believed that he had achieved final awakening and liberation from the cycle of worldly suffering, making him “the Buddha” or enlightened one. Siddhartha founded the oldest monastic order in the world composed of women and men who aspired to follow his example. Other followers of Buddhism include laypeople (or lay practitioners) who practice the Buddha’s teachings but remain within society not joining the monastic order. Lay practitioners have often served as patrons of monastics, supplying them with food, clothing, and shelter in the hopes of earning enough merit to be reborn as monastics themselves in subsequent lifetimes. In modern times, laypersons have become increasingly concerned with spiritual attainment in their current lifetimes, although their role as supporters of monastics remains important.

Like most Han Chinese temples, the Temple of Universal Rescue belongs to Mahayana Buddhism (in Chinese Dacheng Fojiao 大乘佛教), one of three “vehicles” of Buddhist teachings, which is commonly found in East Asian countries. Mahayana Buddhism is based on the ideal of bodhisattvas, who vow not to achieve final awakening until they have saved all other sentient beings from suffering.

Not all those who come to the Temple of Universal Rescue are following a Buddhist religious path. At many times throughout its history, including the present-day, the temple has also functioned as a site for devotional worship in which worshippers bow and, occasionally, make offerings before images of buddhas and bodhisattvas throughout the temple, treating them as deities with magical powers. Many of these worshippers seek the blessings of good health, long life, material prosperity, and many other worldly concerns. Although orthodox Buddhism is based on the belief that one’s present actions entirely determine future consequences, including one’s future rebirth, it has long been customary in most Buddhist countries for laypersons and worshippers to seek the assistance of monastics in carrying out rituals for their deceased loved ones to ensure the loved ones proceed safely to a favorable rebirth. China is no exception to this, and monks at the Temple of Universal Rescue occasionally hold rituals for the correct deliverance of a person’s “soul” to its future rebirth (chaodu 超度). However, as the Temple of Universal Rescue is the headquarter temple of the Chinese Buddhist Association, the temple monks find it important to maintain orthodoxy, and one sees fewer examples of fee-for-service rituals like the deliverance ritual than at Buddhist temples elsewhere in China.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The ordination of new monastics has been an important function of the Temple of Universal Rescue since its ordination platform was constructed in the early Qing dynasty. In addition, recent years have seen biannual lay conversion ceremonies, with several hundred participants at a time. [Image at right] In addition to these, the temple monks lead laypersons and other visitors at weekly Dharma Assemblies (fahui 法会) in a liturgical ritual known as the Chanting of the Sutras (songjing 诵经; See also, Gildow 2014). Dharma Assemblies take place on the first, eighth, fifteenth, and twenty-third days of the lunar month. At various times throughout the year, special assemblies are held with additional rituals and occasionally a sermon. The most notable of these are the celebration of the Buddha’s birthday (yufo jie 浴佛节); the birthday, conversion day, and enlightenment day of the bodhisattva Guanyin; and the Yulanpen day (often known popularly as the Hungry Ghost Festival) in which those who were reborn as “hungry ghosts” (or, one could say, demons [gui 鬼]) are fed and preached the Dharma as an act of compassion. During the Buddha’s birthday, laypersons line up, often for over an

The ordination of new monastics has been an important function of the Temple of Universal Rescue since its ordination platform was constructed in the early Qing dynasty. In addition, recent years have seen biannual lay conversion ceremonies, with several hundred participants at a time. [Image at right] In addition to these, the temple monks lead laypersons and other visitors at weekly Dharma Assemblies (fahui 法会) in a liturgical ritual known as the Chanting of the Sutras (songjing 诵经; See also, Gildow 2014). Dharma Assemblies take place on the first, eighth, fifteenth, and twenty-third days of the lunar month. At various times throughout the year, special assemblies are held with additional rituals and occasionally a sermon. The most notable of these are the celebration of the Buddha’s birthday (yufo jie 浴佛节); the birthday, conversion day, and enlightenment day of the bodhisattva Guanyin; and the Yulanpen day (often known popularly as the Hungry Ghost Festival) in which those who were reborn as “hungry ghosts” (or, one could say, demons [gui 鬼]) are fed and preached the Dharma as an act of compassion. During the Buddha’s birthday, laypersons line up, often for over an  hour, to pour water over a small statue of the baby Buddha as an act of blessing and expression of respect for the great teacher he would become. [Image at right] On the Yulanpen day, the monks lead laypersons in a long nighttime ritual known as the Feeding of the Flaming Mouths (fang yankou 放焰口), so named because it is believed that, as a karmic punishment, ghosts are reborn with tongues of flame in their throat that dissolve all food which enters their mouths before it can nourish their stomachs; during the ritual, the monks, through the power of the Dharma, can circumvent this misfortune, making the ritual the only time the ghosts can receive nourishment. They also hear the preaching of the Dharma which can shorten their time in hell. Laypersons can purchase tablets that temple volunteers adhere to the inside wall of the Yuantong Hall where the ritual takes place. On the tablets are written the names of the sponsors’ deceased loved ones, ensuring that, if reborn as hungry ghosts, the ancestors’ names will be called into the Hall so that they can be fed and preached to.

hour, to pour water over a small statue of the baby Buddha as an act of blessing and expression of respect for the great teacher he would become. [Image at right] On the Yulanpen day, the monks lead laypersons in a long nighttime ritual known as the Feeding of the Flaming Mouths (fang yankou 放焰口), so named because it is believed that, as a karmic punishment, ghosts are reborn with tongues of flame in their throat that dissolve all food which enters their mouths before it can nourish their stomachs; during the ritual, the monks, through the power of the Dharma, can circumvent this misfortune, making the ritual the only time the ghosts can receive nourishment. They also hear the preaching of the Dharma which can shorten their time in hell. Laypersons can purchase tablets that temple volunteers adhere to the inside wall of the Yuantong Hall where the ritual takes place. On the tablets are written the names of the sponsors’ deceased loved ones, ensuring that, if reborn as hungry ghosts, the ancestors’ names will be called into the Hall so that they can be fed and preached to.

In addition to these periodic Dharma Assemblies, the temple monks convene morning devotions (zaoke 早课) and evening devotions (wanke 晚课) that begin and end each day. The morning devotions are held at around 4:45 each morning and the evening devotions at 3:45 in the afternoon. A small number of laypeople also participate in the devotions, particularly the evening ones.

Devotees typically complete a ritual circumambulation of the temple along its central axis. Entering from the southernmost gate, they pass through the outer courtyard, proceeding to the Tianwang 天王Hall, where they make offerings to the future Buddha Maitreya (Mile Pusa 弥勒菩萨) and the bodhisattva Skanda (Weituo pusa 韦驮菩萨). They then proceed into the inner courtyard and the temple’s largest Mahavira Hall (Daxiong Baodian 大雄宝殿) where they make offerings to the Buddhas of Three Realms (Sanshi Fo 三世佛) – Kaśyapa Buddha (Shijiaye Fo 是迦叶佛), Shakyamuni Buddha (Shijiamouni Fo 释迦牟尼佛), and the Buddha that presides over the Paradise of Western Bliss, Amitabha (Amituofo 阿弥陀佛). Finally, they proceed to the northernmost courtyard opened to the public, where they make offerings to Guanyin 观音, the bodhisattva of compassion, whose image resides in the Yuantong 圆通Hall.

The opening of the temple gradually led to it becoming an important site for Beijing residents hoping to discover what religion and Buddhism were about. The lack of an admission fee, the temple’s fame as an historically important temple, and the largely unused large open space of the temple’s outer courtyard made it an ideal space for the discussion of Buddhist teachings and their relation to contemporary problems. Beginning from the 1990s, a wide range of free Buddhist-themed literature and later cassette and video recordings became available in mainland China. These multimedia materials ranged in content. The most plentiful were reproductions of popular Buddhist scriptures such as the Sutra of Infinite Life (Wu Liang Shou Jing 无量寿经), which describes the Paradise of Western Bliss, and the Lotus Sutra (Fahua Jing 法华经), which uses a series of parables to educate readers on the bodhisattva path, the possibility of universal salvation for all sentient beings, and the infinite lifetimes of the Buddha. Other popular texts were morality books (shanshu 善书), which feature entertaining stories that teach correct ethical action and the karmic consequence of both good and bad deeds. Some of these morality books were reproductions of popular morality books from China’s past such as the Ledgers of Merit and Demerit (Gongguoge 功过格); others, however, were authored by contemporary monastics or laypersons and related to karmic lessons to modern-day experiences. Basic introductions to Buddhist teachings, particularly those written by Master Jingkong 净空, a popular Australian-based Chinese Buddhist monk, were also very widely read. One could also find thaumaturgical texts that promised healing, long life, and positive karma to those who recited them. Books and audio and video recordings with sermons by famous monastics and laypeople relating Buddhist teachings to everyday life were also common (See also, Fisher 2011).

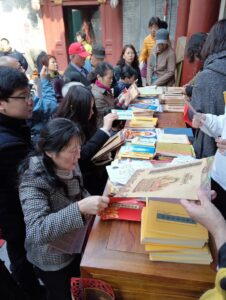

Because the Temple of Universal Rescue was one of the few active Buddhist temples opened to the public in Beijing in the early post-Mao period, it became an important site for the distribution of these multimedia materials, an act which brought merit to the donor. Those who took interest in the materials sometimes stayed to discuss them with fellow lay practitioners in the temple’s spacious outer courtyard. Among those laypersons, some became self-proclaimed experts from reading and viewing the materials, and they would of her work;;;; impromptu sermons on their contents. [Image at right] Hearing these lay teachers begin to address an audience with an excited, raised voice, other listeners in the vicinity would wander over, eager to learn whatever they could about a previously unfamiliar religion. Many of these “preachers” only took on the role once or twice; others, however, developed a regular following and even typed and distributed their own interpretations of Buddhist teachings (See also, Fisher 2014). In addition to the preacher circles and discussion groups, groups that sang and chanted sutras in the courtyard started to become common by around the early 2010s.

The phenomenon of the preacher circles and discussion groups may have had antecedents in the temple’s past. Official histories of the temple predictably focus on its structures, cultural treasures, the practices of its monastics, or its famous visitors. However, there are some accounts of monks and at least one layperson preaching to temple visitors during the early twentieth century (Pratt 1928: 36, Xu 2003: 28). Doubtless, then as now, visitors were attracted by the temple’s important history and reputation as the residence of important monastic teachers from whom they hoped to seek guidance on the Dharma. On arriving at the temple, however, they found it was not often possible to gain an audience with these eminent teachers and so fellow laypersons who offered their own interpretations became an attractive alternative. However, it is also likely that the Buddhist public sphere created in the temple courtyard was at its liveliest in the 1990s and 2000s: During the Cultural Revolution, Buddhist scriptures were destroyed and the public teaching and practice of Buddhism was virtually wiped out, particularly in urban areas. Residents of Beijing had been socialized for a generation in an atheist materialist worldview that saw Buddhism and other religions as fundamentally false and harmful. As restrictions on religious practice were eased from the 1980s, however, many people were curious about this missing part of their heritage and eager to gain whatever information they could find in venues like the outer courtyard of the Temple of Universal Rescue. Moreover, in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, many Chinese citizens experienced an acute loss of meaning in their lives, especially the generation that had been young adults during the Cultural Revolution. Many many had been mobilized as Red Guards, a generation, middle-aged by the century’s turn that was well represented in the outer courtyard’s groups. Mobilized by the ideological fervor of the Cultural Revolution and the belief that they were building global socialism, this generation felt abandoned when the post-Mao state shifted gears to a more pragmatic approach to governance by the late 1970s. With its emphasis on universal compassion, egalitarianism, and the importance of everyday ethical actions, Buddhism provided a source of meaning that, for some, filled this lacunae.

During the height of its popularity as a public religious space, the courtyard contained as many as 300 hundred participants and five active preacher circles at any one time. Participants would arrive as early as 9 a.m. and some stayed until the temple closed at 4:30 p.m. or 5 p.m., with the majority present for the first couple of hours after the end of the Chanting of the Sutras. By the early 2010s, however, the phenomenon started to wane, and, by the end of that decade, it became virtually non-existent (See, Issues/Controversies below).

Since the temple’s re-opening, the monks have also taken an active role in reintroducing Buddhism to laypeople, principally through the teaching of the “lecture on the scriptures” class twice each week for two periods of several weeks each year. Unlike the Dharma Assemblies, which fall on various days of the week in the Western calendar, making them difficult to attend for laypersons on a normal weekly work schedule, the scriptures classes take place on Saturday and Sunday mornings, making them accessible to a wider range of participants. The classes are taught by various monks whose teaching methods vary considerably: some simply lecture while others try to involve their audience. The topic for each class or period of classes also varies; different semesters or even different classes might not necessarily build on each other. My ethnographic research suggests that, as with scriptures classes in temples elsewhere in China, the motivation of participants varies. Some are interested in detailed understanding of Buddhist doctrine to assist in their own practice; others believe that merely by listening to the sermons, they will gain merit and spiritual advancement even if they do not completely comprehend the sermons’ content at a cognitive level.

The temple has also been involved in charity outreach work, dating back to the early nineteenth century, during the Qing dynasty, when the temple monks risked danger by gathering up abandoned bodies on battlefield and performing funeral rites for them (Naquin 2000:650). In the early Republican period (in the early twentieth century), encouraged by reformers both within the state and within Buddhist circles, Buddhists began to engage in charity work. The Temple of Universal Rescue housed a school and provided meals for the needy (Xu 2003:27; Humphreys 1948:106). In the contemporary period, the temple provided funds for the restoration of an elementary school destroyed in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. A donation box for the state-run charitable organization Project Hope (Xiwang Gongcheng 希望工程), which provides schooling in underprivileged parts of the country, stands outside the main Mahavira Hall. However, the present-day temple is less involved in charity work than many other Buddhist temples in China, which run their own charitable foundations.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Leadership of religious sites, including Buddhist ones, in communist China is highly complex (See, for example, Ashiwa and Wank 2006; Huang 2019; Nichols 2020). Not all temples exist as government-authorized religious sites in spite of the presence of religious images, worship practices, or even resident clergy. The Temple of Universal Rescue, as headquarters of the Chinese Buddhist Association, is an officially registered religious site, yet it is also a protected cultural relics site. Even as a religious site, it serves a dual function as a practicing temple in its own right, with its own resident monks, and as the residence of senior monastics within the BAC, as well as headquarters for the offices of the Association. While the daily operation of the temple largely falls to its resident monastics, important decisions about infrastructure or even personnel are made by a number of government and Association bodies.

The temple is led by its abbot (zhuchi 主持). Another important role is filled by the Guest Prefect (zhike 知客) who is responsible for the temple’s relationship to the outside world. Other monastics have specific ritual, administrative, and maintenance duties (See, Welch 1967). As in all Buddhist temples in contemporary China, laypeople also play a significant role in everyday operations. This is in part because there are a relatively small number of monks in relation to the growing number of laypersons and the large number of visitors the temple receives each week, especially during Dharma Assemblies. The temple arranges as many as seventy lay volunteers each week into formal work schedules. Their duties include cooking, cleaning, repair and maintenance, administering the incense urns during Dharma Assemblies, and coordinating and controlling visitors, especially during major ritual events. These volunteer activities are known as “safeguarding the Dharma” (hufa 护法). They are attractive to laypersons as a source of merit as well as an opportunity to create community, particularly for the older, retired volunteers who make up the majority. At various times, the temple has also coordinated younger volunteers, often high school or college-aged students, for major Dharma Assemblies to assist in ritual activities and with crowd control. The activities of these younger volunteers (referred to by the secular term yigong 义工) are part of a recent trend toward civic volunteerism by the generation born after the 1980s. Yigong volunteers, who are not always laypersons, are often motivated more by the desire to try new things and meet new people than the opportunity to earn merit within a Buddhist soteriology.

Additionally, the temple has a small paid staff of temple workers including security guards and maintenance workers.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Historically, Buddhist temples in China have struggled between the demands of worldly society and their functions as spaces of religious retreat. The idea of renunciation is more easily accepted in Buddhism’s birthplace of India than in China. Folk Chinese religion is centered around the family, and Buddhism has always been a potentially disruptive force to that family-centered model of religiosity. Buddhism has suffered persecution on many occasions throughout its long history in China, with the Cultural Revolution being only the most recent example. However, Buddhist practitioners have also adapted to Chinese society by performing rituals for ordinary worshippers, accepting the incorporation of buddhas and bodhisattvas into the Chinese pantheon, and accommodating deeply cherished Chinese values such as respect for ancestors through rituals like the Feeding of the Flaming Mouths. The modern Temple of Universal Rescue reflects these tensions being, on the one hand, a space for monastic retreat, at times surprisingly quiet and calm within a busy city and, on the other, a space for popular religious practice. Its important administrative function as the headquarters of the Chinese Buddhist Association reflects the need for Chinese Buddhism to be responsible and responsive to an atheist state that still regards religion with suspicion.

Few monastics in China today would insist that Buddhist temples be kept exclusively as spaces for monastic retreat with no public functions, and many (though not most) are involved in outreach to the laity and the general public. However, there are lines that monastics and other temple administrators wish to be drawn, even if they do not always get their way. In recent years, at the Temple of Universal Rescue, much of this has concerned the activities of the preacher circles and discussion groups in the temple’s outer courtyard.

During the longest period of my ethnographic research at the temple in the early 2000s, the temple monks, their longstanding lay students, and, occasionally, leaders in the Association expressed concern about the activities of the preacher circles and discussion groups, in particular the unregulated distribution of multi-media materials in the courtyard. These leaders of the temple felt, understandably, that they, and not amateur preachers with no religious credentials, had both the right and the responsibility to say what were orthodox Buddhist teachings. For both religious and political reasons, the temple authorities were particularly concerned that the public learn to distinguish “true” Buddhist teachings from folk religious beliefs or, even more crucially, banned teachings like those of the Falun Gong spiritual movement, which had appropriated many Buddhist symbols and concepts. Yet for much of the early 2000s, the temple authorities lacked a regulatory apparatus to fully control the courtyard groups: there was a leadership vacuum at the temple, which was absent an abbot for several years, and a lack of interest from government authorities outside of the temple.

With the appointment of a new abbot, the mid-2000s saw the steady erection of signs in the courtyard warning the public that all distributed religious materials had to be approved first by the temple’s guest office and frowning on unauthorized public preaching. For several years, however, signs such as these were largely ignored, and the activities of the preacher circles and discussion groups went on as before. By the early 2010s, however, the temple worked more actively to take control of the space: it parked a large number of cars there and began to set up stalls to sell Buddhist-themed merchandise. [Image at right] The increased use of the courtyard created more congestion. During one major Dharma Assembly I attended, one of the young yigong volunteers broke up a preacher circle that was blocking the only entrance to the inner courtyard, resulting in a shouting match between the volunteer and the preacher. For the preacher, who had studied Buddhist teachings on his own for many years and freely preached on his knowledge to an interested audience each week, being disrupted by a teenager who likely knew little about Buddhism was extremely humiliating. The volunteer, however, believed he had been given the important responsibility of ensuring people could move smoothly between ritual activities organized by the temple monks, whose rightful authority the preacher was attempting to usurp.

By the mid-2010s, under the presidency of Xi Jinping, the temple leaders received more support from outside authorities to control their own space and became more proactive in forcing the preachers to cease their unscheduled sermons. They confined the distribution of Buddhist-themed literature and multi-media materials to one table in the inner courtyard that was policed by lay volunteers.

In spite of this, the Temple of Universal Rescue remains a vibrant religious site for monastics and laypersons, with an active ritual program, the continuation of the scriptures classes, and the continued availability of a wide range of free Buddhist materials to read and view. [Image at right] While the lay preachers cannot continue to preach, some have taken their followings elsewhere; others remain at the temple to participate in ritual activities. Longtime practitioners still seek out their advice, albeit more discreetly, and direct others to do so as well. Many practitioners, especially elderly ones, continue to gather in the inner and outer courtyard to socialize, discuss Buddhist scriptures, and gain some relief from the heat in the summer months. Overall, the Temple of Universal Rescue is a showpiece to the tenacity of Buddhism’s appeal even in one of the most secular of global cities.

IMAGES

Image #1: A lay conversion ceremony at the Temple of Universal Rescue.

Image #2: Celebration of Buddha’s birthday at the Temple of Universal Rescue.

Image #3: An impromptu sermon at the Temple of Universal Rescue.

Image #4: Stalls set up to sell Buddhist-themed merchandise at the Temple of Universal Rescue.

Image #5: Free Buddhist materials to read and view provided by laypeople as an act of merit-making.

REFERENCES

Ashiwa, Yoshiko and David L. Wank. 2006. “The Politics of a Reviving Buddhist Temple: State, Association, and Religion in Southeast China.” Journal of Asian Studies 65:337-60.

Fisher, Gareth. 2014. From Comrades to Bodhisattvas: Moral Dimensions of Lay Buddhist Practice in Contemporary China. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press.

Fisher, Gareth. 2011. “Morality Texts and the Re-Growth of Lay Buddhism in China.” Pp. 53-80 in Religion in Contemporary China: Tradition and Innovation, edited by Adam Yuet Chau. New York: Routledge.

Gildow, Douglas M. 2014. “The Chinese Buddhist Ritual Field: Common Public Rituals in PRC Monasteries Today.” Journal of Chinese Buddhist Studies 27:59-127.

Huang Weishan. 2019. “Urban Restructuring and Temple Agency – a Case Study of the Jing’an Temple.” Pp. 251-70 in Buddhism after Mao: Negotiations, Continuities, and Reinventions, edited by Ji Zhe, Gareth Fisher, and André Laliberté. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Humphreys, Christmas. 1948. Via Tokyo. New York: Hutchison and Co.

Li Yao 李瑶 and Madelyn Bjork. 2020. “Guangji Temple.” Pp. 92-105 in Religions of Beijing, edited by You Bin and Timothy Knepper. New York: Bloomsbury Academic Press.

Naquin, Susan. 2000. Peking: Temples and City Life, 1400-1900. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Nichols, Brian J. 2020. “Interrogating Religious Tourism at Buddhist Monasteries in China.” Pp. 183-205 in Buddhist Tourism in Asia, edited by Courtney Bruntz and Brooke Schedneck. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press.

Pratt, James Bissett. 1928. The Pilgrimage of Buddhism and a Buddhist Pilgrimage. New York: Macmillan Press.

Welch, Holmes. 1967. The Practice of Chinese Buddhism, 1900-1950. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Xu Wei 徐威. 2003. Guangji si 广济寺. Beijing: Huawen Chubanshe.

Publication Date:

9/18/2021