CHARLOTTE FORTEN GRIMKÉ TIMELINE

1837 (August 17): Charlotte Forten was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to Robert Bridges Forten and Mary Virginia Wood Forten.

1840 (August): Charlotte’s mother died from tuberculosis.

1850: The U.S. Congress passed Fugitive Slave Act, which required seizure and return of runaway slaves who had escaped from slave-owning states; it was repealed in 1864.

1853 (November): Charlotte Forten moved from Philadelphia to Salem, Massachusetts to the home of the Charles Lenox Remond family.

1855 (March): Charlotte Forten graduated from the Higginson Grammar School and enrolled in Salem Normal School (now Salem State University).

1855 (September): Forten joined the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society.

1856 (June/July): Forten graduated from Salem Normal School and took a teaching position at the Eppes Grammar School in Salem.

1857 (March 6): The U.S. Supreme Court handed down the Dred Scott decision, which stated that African Americans were not and never could be U.S. citizens.

1857 (Summer): Forten went to Philadelphia to recuperate from illness, then returned to Salem to continue teaching.

1858 (March): Forten resigned her position at Eppes Grammar School due to ill health and returned to Philadelphia.

1859 (September): Forten returned to Salem to teach at the Higginson Grammar School.

1860 (October): Forten resigned Salem post due to continued poor health.

1861 (April 12): The U.S. Civil War began.

1861 (Fall): Forten taught in Philadelphia’s Lombard Street School, run by her paternal aunt Margaretta Forten.

1862 (October): Forten left for South Carolina to teach under auspices of Port Royal Relief Association.

1862 (December): Forten’s written accounts of her experiences in South Carolina were published in the national abolitionist journal The Liberator.

1863 (July): Forten nursed wounded soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts regiment after their defeat at Fort Wagner, South Carolina.

1864 (April 25): Forten’s father died of typhoid fever in Philadelphia.

1864 (May/June): Forten’s two-part essay “Life on the Sea Islands” was published in the Atlantic Monthly.

1865 (May 9): The U.S. Civil War ended.

1865 (October): Forten accepted a position as Secretary of the Teachers Committee of the New England Branch of the Freedman’s Union Commission in Boston, Massachusetts.

1871: Forten was employed as a teacher at the Shaw Memorial School in Charleston, South Carolina.

1872–1873: Forten taught at Dunbar High School, a Black preparatory school in Washington, D.C.

1873–1878: Forten took a position as first-class clerk in the Fourth Auditor’s Office of the U.S. Treasury Department.

1878 (December 19): Forten married the Reverend Francis Grimké, minister of the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church in Washington, D.C.

1880 (January 1): Forten Grimké’s daughter, Theodora Cornelia Grimké, was born.

1880 (June 10): Theodora Cornelia Grimké died.

1885–1889: Charlotte Grimké and her husband moved to Jacksonville, Florida where Francis Grimké was minister of the Laura Street Presbyterian Church.

1888 to late 1890s: Charlotte Forten Grimké continued to write and publish poetry and essays.

1896: Forten Grimké became a founding member of the National Association of Colored Women.

1914 (July 22): Charlotte Forten Grimké died in Washington, D.C.

BIOGRAPHY

Charlotte Louise Bridges Forten [Image at right] was born on August 17, 1837 at 92 Lombard Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the home of her grandparents, a leading free Black family in the city that was active in the abolitionist movement (Winch 2002:280). She was the grandchild of James and Charlotte Forten, and the only child of their son Robert Bridges Forten and his first wife, Mary Virginia Wood Forten, who died of tuberculosis when Charlotte was three years old. Named after her grandmother, Charlotte was a fourth-generation free Black woman on her paternal side (Stevenson 1988:3). Her grandfather was the eminent James Forten, a reformer and antislavery activist who owned a successful sail-making business in Philadelphia, at one point amassing a fortune of more than $100,000, a huge sum for the times. Charlotte Forten grew up in relative economic security, was privately tutored, traveled widely, and enjoyed a variety of social and cultural activities (Duran 2011:90). Her extended family was deeply committed to ending slavery and combating racism. James Forten played a central role in the American Anti-Slavery Society and was a friend and supporter of the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison (1805–1879). The Forten women helped found the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Her aunts, Sarah, Margaretta, and Harriet Forten, used their intellectual gifts to advance the antislavery movement (Stevenson 1988:8).

The Fortens were part of a large network of prosperous, well-educated, and socially active African Americans in New York, Boston, and Salem, Massachusetts, all of them engaged in the abolition movement. But by the early 1840s, the firm of James Forten & Sons declared bankruptcy and money did not flow as freely in the extended family (Winch 2002:344). Charlotte was sent to Salem in 1853 to live with the Remonds a few years after the death of her grandmother, Edy Wood, who had been raising Charlotte after her mother’s death. Forten grieved the loss of her mother and grandmother and her later estrangement from her father, who had moved with his second wife, first to Canada, and then to England. Charles Remond of Salem, the son of a successful caterer, had married Amy Williams, a former neighbor of the Fortens in Philadelphia, and they became a welcoming family to Charlotte Forten. Both Charles and Amy Remond were key players in the abolition network and were frequently visited in their home by such antislavery luminaries as Garrison, William Wells Brown, Lydia Marie Child, and John Greenleaf Whittier (Salenius, 2016:43). Salem had desegregated its schools in 1843, the first town in Massachusetts to do so (Noel 2004:144). Forten’s father sent her to Salem to attend a desegregated school, and she enrolled in the Higginson Grammar School for Girls under the tutelage of Mary L. Shepard whom Forten warmly referred to as her friend and “dear, kind teacher” (Grimké 1988: September 30, 1854:102).

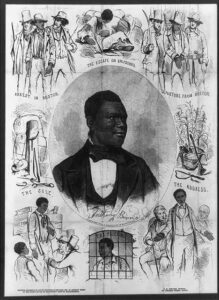

With her move to Massachusetts in 1854, Forten was a contemporary witness to the brutal effect of the federal Fugitive Slave Law (1850), which required seizure and return of runaway slaves who had escaped from slave-owning states. On Wednesday, May 24, 1854, an arrest warrant was issued in Boston for a fugitive slave, Anthony Burns. [Image at right] His trial riveted the abolitionist community, including Forten. The court found in favor of Burns’ owner, and Massachusetts prepared to return him to slavery in Virginia. Forten’s journals convey her outrage at this injustice, as she wrote:

Our worst fears are realized; the decision was against poor Burns, and he has been sent back to a bondage worse, a thousand times worse than death. . . . To-day Massachusetts has again been disgraced; again has she showed her submissions to the Slave Power. . . . With what scorn must that government be regarded which cowardly assembles thousands of soldiers to satisfy the demands of slaveholders; to deprive of his freedom a man, created in God’s own image, whose sole offense is the color of his skin! (Grimké 1988:June 2, 1854:65–66)

Her early journals, written while living in Salem, reveal a persistent sense of unworthiness. In June 1858, she wrote:

Have been under-going a thorough self-examination. The result is a mingled feeling of sorrow, shame and self-contempt. Have realized more deeply and bitterly than ever in my life my own ignorance and folly. Not only am I without the gifts of Nature, wit, beauty and talent; without the accomplishments which nearly every one of my age, whom I know, possesses; but I am not even intelligent. And for this there is not the shadow of an excuse (Grimké 1988:June 15, 1858:315–16).

As Forten matured, these self-critical thoughts seem to have subsided, and she pioneered many accomplishments as a Black woman. She had been the first Black student to have been admitted to Salem Normal School, and the first Black public school teacher in Salem. She became a well-published author and traveled to the South during the Civil War to teach newly freed slaves. She was highly regarded in prominent abolitionist circles and participated in the founding of reform organizations.

Forten’s father had wanted her to attend Salem Normal School (now Salem State University) to prepare for a career in teaching. Charlotte herself had not expressed interest in this path; her father had seen it as a way for Charlotte to support herself. She desired to please her father and was determined to find ways to uplift her race. “I will spare no effort to become what he desires that I should be . . . a teacher, and to live for the good that I can do my oppressed and suffering fellow creatures” (Grimké 1988:October 23, 1854:105). Forten considered her opportunity to engage in advanced study a blessing that suggested God had chosen her for an important mission: to use her talents to improve the lives of Black Americans. Through unswerving devotion to this idea, she sometimes denied herself personal pleasure and happiness.

On March 13, 1855, seventeen-year-old Charlotte Forten passed her entrance examination and enrolled in the second class of Salem Normal School. [Image at right] One of forty students, she did not have financial assistance from her father; her teacher Mary Shepard offered to pay or loan Forten the money for her education. Forten thrived intellectually at the school. Her low self-esteem was fueled by the insidious racism of the society in which she lived. Of course, Salem, Massachusetts of the 1850s and 1860s was progressive enough that she could attend an excellent teacher training school and be hired as a teacher in the city’s public schools. But her diary records the many slights she suffered from her classmates’ prejudice, and the pain of this made it difficult for Forten to maintain what she considered Christian fortitude:

I long to be good, to be able to meet death calmly, and fearlessly, strong in faith and holiness. But this I know can only be through the one who died for us, through the pure and perfect love of Him, who was all holiness and love. But how can I hope to be worthy of his love while I still cherish the feeling toward my enemies, this unforgiving spirit . . . hatred of oppression seems to me to be so blended with hatred of the oppressor I cannot seem to separate them (Grimké 1988: August 10, 1854:95).

The following year, Forten wrote:

I wonder that every colored person is not a misanthrope. Surely, we have everything to make us hate mankind. I have met girls in the schoolroom—they have been thoroughly kind and cordial to me—perhaps the next day met them in the street—they feared to recognize me; these I can but regard now with scorn and contempt, once I liked them, believing them incapable of such measures (Grimké 1988: September 12, 1855:140).

Forten persisted, though, believing that her scholarly advancement would “aid me in fitting myself for laboring in a holy cause, for enabling me to do much towards changing the condition of my oppressed and suffering people” (Grimké 1988:June 4, 1854:67). Later, she would expand on this vision:

We are a poor, oppressed people, with very many trials, and very few friends. The Past, the Present, the Future are alike dark and dreary for us. I know it is not right to feel thus. But I cannot help it always; though my own heart tells me that there is much to live for. That the more deeply we suffer, the nobler and holier is the work of life that lies before us! Oh! for strength; strength to bear the suffering, to do the work bravely, unfalteringly! (Grimké 1988: September 1, 1856:163–64).

Her firm Christian beliefs carried her through these challenging times, and she fully immersed herself in her academic work.

Forten performed well at the Normal School’s final examinations and was selected to write the class hymn for the graduating class of 1856. She began teaching at the Epps Grammar School in Salem on the day after her graduation, a position secured for her by the principal of Salem Normal, Richard Edwards. Her salary was $200 per year. The death of her beloved friend Amy Remond and her own continuing poor health plagued Forten during this time, and she resigned the position in March 1858, returning to Philadelphia to recover. Upon leaving her teaching post in Salem in 1858, Forten was commended by the Salem Register for her contributions. According to the article, Forten was highly successful in her educational endeavors, and “graciously received by the parents of the district,” despite being a “young lady of color, identified with that hated race whose maltreatment by our own people is a living reproach to us as a professedly Christian nation” (quoted in Billington 1953:19). The article suggested the praise for the “experiment” largely redounded to the Salem community which congratulated itself on its progressiveness (Noel 2004:154).

Forten returned to Salem in 1859 to teach at the Higginson School with Mary Shepard and enrolled in Salem Normal School’s Advanced Program. The famed Salem navigator, Nathaniel Ingersoll Bowditch, was her benefactor (Rosemond and Maloney 1988:6). She completed two terms before the outbreak of the Civil War. Then, in 1862, Forten answered the call to help in the education of newly freed persons in the Gullah communities in the Sea Islands in South Carolina.

This passion led to her decision to leave her teaching program to prepare for moving to the South to assist newly freed men and women. Union military officials had classified all land, property, and slaves on St. Helena Island in Beaufort County, South Carolina as “contrabands of war,” but it quickly became apparent that policies needed to be developed to deal with the major social and economic changes that resulted from their liberation. After years of perseverance in working toward her dream of useful, challenging, and satisfying reform work, she found it in the Port Royal Relief Association, headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Forten worked as a teacher in Beaufort County, South Carolina for more than a year, demonstrating what she had always declared in her journals: that Black people could be taught to excel academically. Forten found that educating the most downtrodden of her race was both rewarding and exhilarating. Forten partnered with other Northern teachers and immersed herself in the stories and music of the Creole-speaking Gullah islanders who lived there.

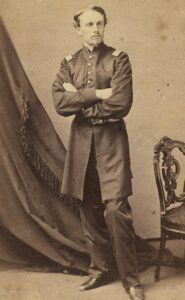

Thomas Wentworth Higginson, commander of the formerly enslaved first South Carolina Volunteers, appreciated that she taught many of his men to read, and was a close friend. Forten also writes affectionately of her meeting with Col. Robert Gould Shaw, [Image at right] the commander of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment consisting of African American soldiers (Grimké 1988:July 2, 1863:490). During the summer of 1863, the Union forces set out to conquer the port of Charleston. Col. Shaw led his 54th regiment in the doomed attack on Fort Wagner, in which scores of men, including Shaw, were killed. Forten waited to hear the outcome of the battle for two weeks from secluded St. Helena Island, and mourned the losses in her journal: “To-night comes news oh, so sad, so heart sickening. It is too terrible, too terrible to write. We can only hope it may not all be true. That our noble, beautiful Colonel [Shaw] is killed, and the regt. cut to pieces. . . . I am stunned, sick at heart . . . I can scarcely write. . . .” (Grimké 1988: Monday, July 20, 1863:494). Shaw was only a month younger than Forten when he died at age twenty-five. The next day, Forten volunteered as a nurse for the soldiers. Forten later wrote of her experiences, and in 1864, her two-part essay, “Life on the Sea Islands,” was published in the May and June issues of The Atlantic Monthly.

The following October 1865, Forten came back to Boston, Massachusetts, having accepted a position as Secretary of the Teachers Committee of the New England Branch of the Freedman’s Union Commission. She lived in Massachusetts for six years before making arrangements to return to the South. During this period, she published her translation of Madame Thérèse (1869) and published in the Christian Register, the Boston Commonwealth, and The New England Magazine (Billington 1953:29). In fall 1871, Forten began a year of teaching at the Shaw Memorial School in Charleston, South Carolina, named after her friend, the late Robert Gould Shaw. She continued to teach the following year at a preparatory school for young Black men in Washington, D.C., later called Dunbar High School. Following that second year of teaching, Forten was offered a position as first-class clerk in the Fourth Auditor’s Office of the U.S. Treasury Department. She worked for five years in this role, from 1873–1878.

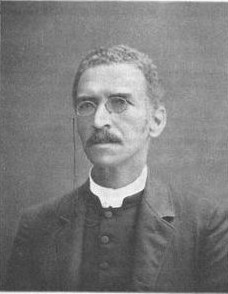

In 1878, at the age of forty-one, Forten married Reverend Francis Grimké, [Image at right] the twenty-eight-year-old minister of the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church in Washington, D.C. Thirteen years her junior, he was the manumitted Black nephew of White abolitionists Angelina and Sarah Grimké originally from a wealthy Charleston, South Carolina slave-owning family. Francis Grimké was intelligent, sensitive, and fiercely dedicated to his profession and the advancement of his race. The couple had one daughter who died in infancy, a deeply affecting loss. Charlotte Forten Grimké died July 22, 1914.

TEACHINGS/DOCTRINES

Forten was an ardently spiritual Christian believer. From a young age, she idolized her deceased mother as angelic and would have heard stories of her parent’s exceptional piety. Mary Virginia Wood Forten’s obituary in The Colored American quoted her saying as she lay dying, “You are moral and good but you need religion, you need the grace of God. O seek it!” (quoted in Glasgow 2019:38). Forten felt her mother’s loss keenly throughout her life, even though several other women mentors stepped in to help fill the role.

In her early journals, Forten expressed interest in the Spiritualism movement, which was then all the vogue, especially among abolitionists. Several prominent thinkers and writers were intrigued with the concept, including Garrison, who believed that it was possible to communicate with the dead through a medium. William Cooper Nell (1816–1874) was a prominent Black abolitionist and believer in Spiritualism, and a close friend of Forten’s. In August 1854, Forten made a few entries in her journal that touched on Spiritualism. On Tuesday, August 8, 1854, Forten wrote of walking through Harmony Grove Cemetery in Salem with her beloved teacher, Mary Shepard:

Never did it look so beautiful as on this very loveliest of summer mornings, so happy, so peaceful one almost felt like resting in that quiet spot, beneath the soft, green grass. My teacher talked to me of a beloved sister who is sleeping here. As she spoke, it almost seemed to me as if I had known her; one of those noble, gentle, warm-hearted spiritual beings, too pure and heavenly for this world (Grimké 1988: August 8, 1854:94).

A few days after this walk, Forten began reading Nathaniel Hawthorne’s mystical story of revenge, The House of the Seven Gables, and it affected her deeply. She wrote

That strange Mysterious, awful reality, that is constantly around and among us, that power which takes away from us so many of those whom we love and honor. . . . I feel that no other injury could be so hard to bear, so very hard to forgive, as that inflicted by cruel oppression and prejudice. How can I be a Christian when so many in common with myself, for no crime suffer so cruelly, so unjustly? It seems in vain to try, even to hope. And yet I still long to resemble Him that is really good and useful in life (Grimké 1988:August 10, 1854:95)

Finishing the novel in just a few days, Forten records a conversation with Nell on the day before her seventeenth birthday “about the ‘spiritual rappings’.”

He is a firm believer in their “spiritual” origin. He spoke of the different manner in which the different “spirits” manifested their presence,—some merely touching the mediums, others thoroughly shaking them, etc. I told him that I thought I required a very “thorough shaking” to make me a believer. Yet I must not presume to say that I entirely disbelieve that which the wisest cannot understand (Grimké 1988:August 16, 1854:96)

Spiritualism was again on her mind in November 1855, as she again walked through Harmony Grove and spied the tombstone of a friend who had passed away. Forten wrote, “Hard is it to realize that beneath lie the remains of one who was with us a few short months ago! The belief of the Spiritualists is a beautiful, and must be a happy one. It is that the future world is on the same plan as this, but far more beautiful and without sin” (Grimké 1988:November 26, 1855:145).

On August 5, 1857, Forten wrote of hearing an oration by a theologian at Church, “Most of it was excellent; but there was one part—a tirade against Spiritualism, which I disliked exceedingly; it seemed to me very inappropriate and uncharitable” (Grimké 1988:244). But in 1858, Forten again expressed skepticism about it, “This afternoon a little girl professing to be a medium, came in. Some raps were produced, but nothing more satisfactory. I grow more and more skeptical about Spiritualism” (Grimké 1988:January 16; 1858:278).

That same year, however, Forten penned a poem called “The Angel’s Visit” (Sherman 1992:213–15). Certainly, some lines from the poem seem compatible with a belief in Spiritualism:

“On such a night as this,” methought,

“Angelic forms are near;

In beauty unrevealed to us

They hover in the air.

O mother, loved and lost,” I cried,

“Methinks thou’rt near me now;

Methinks I feel thy cooling touch

Upon my burning brow.“O, guide and soothe thy sorrowing child;

And if ‘tis not His will

That thou shouldst take me home with thee,

Protect and bless me still;

For dark and drear had been my life

Without thy tender smile,

Without a mother’s loving care,

Each sorrow to beguile.”

After this spiritual crisis, the poem continues,

I ceased: then o’er my senses stole

A soothing dreamy spell,

And gently to my ear were borne

The tones I loved so well;

A sudden flood of rosy light

Filled all the dusky wood,

And, clad in shining robes of white,

My angel mother stood.She gently drew me to her side,

She pressed her lips to mine,

And softly said, “Grieve not, my child;

A mother’s love is thine.

I know the cruel wrongs that crush

The young and ardent heart;

But falter not; keep bravely on,

And nobly bear thy part.“For thee a brighter day’s in store;

And every earnest soul

That presses on, with purpose high,

Shall gain the wished-for goal.

And thou, beloved, faint not beneath

The weary weight of care;

Daily before our Father’s throne

I breathe for thee a prayer.“I pray that pure and holy thoughts

May bless and guard thy way;

A noble and unselfish life

For thee, my child, I pray.”

She paused, and fondly bent on me

One lingering look of love,

Then softly said, —and passed away, —

“Farewell! we’ll meet above.”

Though the poem concludes with the speaker’s realization that it was a dream from which she “woke,” the concept of communing with the dead so central to Spiritualism becomes a comfort to the speaker who finds her despair soothed, and a closer connection to God.

The injustices of her society took an emotional toll on Forten. While her early diaries indicate she suffered from depression, her staunch commitment to Christianity prevented her from thoughts of self-harm, as she believed only God could shape a person’s life course (Stevenson 1988:28). As an adolescent and young adult, Forten was often highly self-critical and condemned herself as selfish for not working harder to fulfill lofty Christian ideals. This was the theme of her graduation hymn, first published in the Salem Register, July 16, 1855. Later published as a poem called, “The Improvement of Colored People,” in The Liberator, the national journal of the abolition movement, August 24, 1856, the opening verse underscores the idea of Christian obligation:

In the earnest path of duty,

With the high hopes and hearts sincere,

We, to useful lives aspiring,

Daily meet to labor here (Stevenson 1988:25).

Forten wrote another hymn, also published in the Salem Register, February 14, 1856, which was sung during the Salem Normal School examination program:

When Winter’s royal robes of white

From hill and vale are gone,

And the glad voices of the spring

Upon the air are borne,

Friends, who have met with us before,

Within these walls shall meet no more.Forth to a noble work they go:

O, may their hearts keep pure,

And hopeful zeal and strength be theirs

To labor and endure,

That they an earnest faith may prove

By words of truth and deeds of love.May those, whose holy task it is

To guide impulsive youth,

Fail not to cherish in their souls

A reverence for truth;

For teachings which the lips impart

Must have their source within the heart.May all who suffer share their love—

The poor and the oppressed;

So shall the blessing of our God

Upon their labors rest.

And may we meet again where all

Are blest and freed from every thrall.

The hymn meditates upon the important role of the teacher, especially in uplifting the downtrodden. The reference to being “freed from every thrall” speaks to the poem’s abolitionist theme. Forten held out hope that teachers would rise to the challenges of the times.

It seems her faith was more easily placed with teachers than with ordained members of the ministry. Like many abolitionists, Forten was concerned that the institution of slavery tainted American Christianity. In an early discussion with her mentor Mary Shepard, Charlotte writes that Shepard, while thoroughly opposed to slavery, “does not agree with me in thinking that the churches and ministers are generally supporters of the infamous system; I believe it freely (Grimké 1988:May 26, 1854:60–61). Forten shared the belief common to Garrisonian abolitionists that slavery had deeply infected “American Christianity” and appraised the ministers she encountered by this measure. Following the Anthony Burns ruling, Forten wondered in her journal “how many Christian ministers to-day will mention him, or those who suffer with him? How many will speak from the pulpit against the cruel outrage on humanity which has just been committed, or against the many, even worse ones, which are committed in this country every day?” (Grimké 1988:June 4, 1854:66) In answer to her own rhetorical question, Forten responds, “Too well do we know that there are but very few, and these few alone deserve to be called the ministers of Christ, whose doctrine was ‘Break every yoke, and let the oppressed go free’” (Grimké 1988:66). After attending an anti-slavery lecture by a Watertown, Massachusetts minister, Forten praised him as “one of the few ministers who dare speak and act as freemen, obeying the Higher Law, and scorning all lower laws which are opposed to Justice and Humanity” (Grimké 1988:November 26, 1854:113).

Despite Grimké’s continued skepticism about the purity of American churches, she remained a devout Christian throughout her life. After her death, her niece, Angelina Weld Grimké (2017), extolled her in a touching poem, “To Keep the Memory of Charlotte Forten Grimké.” The four-stanza poem ends with this summation of her spirituality:

Where has she gone? And who is there to say?

But this we know: her gentle spirit moves

And is where beauty never wanes,

Perchance by other streams, ’mid other groves;

And to us here, ah! she remains

A lovely memory

Until Eternity;

She came, she loved, and then she went away.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

In addition to participating in the rituals of Christian life, Charlotte Forten’s primary meditative practice was to maintain a journal. She began writing her diary on May 24, 1854 at age fifteen, having moved to Salem, Massachusetts to attend the newly integrated public schools in that city. In embracing this genre, she was engaging with a form of writing that signaled female gentility. In the introduction to her journal, Forten declared that one of the purposes of her diary was “to judge correctly of the growth and improvement of my mind from year to year” (Stevenson 1988:58). The journals span thirty-eight years, including the antebellum period, the Civil War, and its aftermath. There are five distinct journals:

Journal 1, Salem (Massachusetts), May 24, 1854 to December 31, 1856;

Journal 2, Salem, January 1, 1857 to January 27, 1858;

Journal 3, Salem, January 28, 1858; St. Helena Island (South Carolina), February 14, 1863;

Journal 4, St. Helena Island, February 15, 1863 to May 15, 1864;

Journal 5, Jacksonville (Florida), November 1885, Lee (Massachusetts), July 1892.

Historian Ray Allen Billington wrote that Forten “kept her journal in ordinary board-covered notebooks, writing in ink in a cultivated and legible hand” (Billington 1953:31). Grimké’s journals are now archived in the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University.

Between October 28, 1862 and May 15, 1864, Forten chronicled her life among the South Carolina Sea Island “contrabands,” enslaved persons who escaped to assist Union forces during the Civil War. It was during this period that she began to speak to her journal as “Ami,” French for “friend.” She detailed her encounters with the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the 1st and 2nd South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiments consisting of former slaves, and the culture of the Gullah people who inhabited the forfeited plantations of the island. With an ethnographer’s eye, Forten chronicled the social structures of the Gullah/Geechee peoples who lived off the coasts of South Carolina and Georgia on the Sea Islands. Sharing the locale with luminaries such as Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, and personally meeting with Harriet Tubman who led the 2nd South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment in the Raid at Combahee Ferry, Forten was indeed an eyewitness to important moments in the Civil War. Her status as an elite Black female abolitionist and intellectual renders her journals historically significant.

Charlotte Forten movingly records the arrival of the hour of freedom on Thursday, New Year’s Day, 1863, when the Emancipation Proclamation was read to a crowd of slaves that had been placed under the protection of the Union Army. She wrote:

It all seemed, and seems still, like a brilliant dream. . . . As I sat on the stand and looked around on the various groups, I thought I had never seen a sight so beautiful. There were the black soldiers, in their blue coats and scarlet pants, the officers of this and other regiments in their handsome uniforms, and crowds of lookerson, men, women and children. . . . Immediately at the conclusion, some of the colored people—of their own accord sang “My Country Tis of Thee.” It was a touching and beautiful incident (Grimké 1988:New Year’s Day, January 1, 1863:429–30).

In her journals and in her letters published in The Liberator, Forten meticulously described the people and culture of the Sea Islands. She presented them as God-fearing, polite, industrious people who were grateful to the Union Army for liberating them from slavery, humanizing her subjects and depicting them sympathetically. On November 20, 1862, the following letter from Forten was published in The Liberator:

As far as I have been able to observe—and although I have not been here long, I have seen and talked with many of the people—the Negroes here seem to be, for the most part, an honest, industrious, and sensible people. They are eager to learn; they rejoice in their new-found freedom. It does one good to see how jubilant they are over the downfall of their “secesh” masters, as they call them. I do not believe that there is a man, woman, or even a child that is old enough to be sensible, that would submit to being made a slave again. There is evidently a deep determination in their souls that never shall be. Their hearts are full of gratitude to the Government and the “Yankees.”

Emphasizing the steady and rapid progress made by her pupils, Forten wrote in her essay, “Life on the Sea Islands,” published in the Atlantic Monthly, 1864:

I wish some of those persons at the North, who say the race is so hopelessly and naturally inferior, could see the readiness with which these children, so long oppressed and deprived of every privilege, learn and understand.

Forten strongly argued that once freed from the horrors of slavery and given the opportunities of education, these formerly enslaved persons would prove to be responsible citizens. One scholar describes the journals this way: “The journals of Charlotte Forten are a hybrid mixture of diary writing, autobiography proper, and racial biography” (Cobb-Moore 1996:140). As an extensive cultural record, Forten’s journals explore her anomalous position as an elite Black woman in a white world and vividly trace her education and her development as a social reformer. The journals critically probe nineteenth-century constructs of womanhood and facilitate the development of both Forten’s political and artistic consciousness. Forten’s sophisticated rhetoric in her journals [Image at right] built on her awareness of them as future public documents intended for posterity that balanced a highly literate elicitation of sympathy with incisive criticism of racial injustice in the United States. Australian scholar Silvia Xavier has argued that Forten deserves recognition for her radical use of rhetoric to advance the cause of ending slavery (2005:438). “Forten’s work attests to the gulf between rhetoric and reality that belies the ‘democratizing’ culture of this period, revealing the limitations of the cultural and social role of rhetorical pedagogy in its failure to address the issue of race” (Xavier 2005:438). Xavier notes Forten also adopts nineteenth-century rhetorical practices that successfully mediate between speaker and auditor to elicit sympathy, move passions, and incite action (Xavier 2005:438), a familiar strategy for abolitionist literature. In later life, Forten Grimké wrote fewer entries; her final entry is dated July 1892 from Lee, Massachusetts, as she often spent a few summer weeks in the Berkshires to try to improve her health (Maillard 2017:150–51).

LEADERSHIP

From her earliest upbringing, Forten was involved in abolition work. Newly arrived in Salem, Forten helped the Remonds advocate for the freeing of captured runaway Anthony Burns. While studying in Salem, Forten sewed clothing and other articles to raise funds at fairs for abolitionist activities, such as the New England Anti-Slavery Christmas Bazaar in Boston. Forten made important contributions to nineteenth-century literary productions by African Americans, publishing accounts of her experiences in South Carolina in the prestigious Atlantic Monthly. As the Civil War ended, she moved to Boston in October 1865, where she became Secretary of the Teachers Committee of the New England Branch of the Freedmen’s Union Commission, recruiting and training teachers of freed enslaved people until 1871 (Sterling, 1997:285). She continued her work as a leading Black intellectual and linguist. In 1869, her translation of Emile Erckman and Alexandre Chartrain’s French novel, Madame Thérèse; or the Volunteers of ’92 was published, although her name does not appear on the edition. Billington quotes from a note by the publisher, likely from one of the editions, that states, “Miss Charlotte L. Forten has performed the work of translation with an accuracy and spirit which will, undoubtedly, be appreciated by all acquainted with the original” (Billington 1953:210). The following year, when she was living in Philadelphia with her grandmother and teaching in her aunt’s school, the census records her occupation as “Authoress” (Winch 2002:348).

Forten remained active in the struggle for her people even during lapses in her teaching career. She remained deeply committed to a life of service. Forten returned to the South for a year to teach freedmen in Charleston at a school named in honor of Robert Gould Shaw; in 1871, she taught at a Black preparatory school in Washington, D.C. For five years, from 1873 to 1878, she worked as a statistician in the Fourth Auditor’s Office of the U.S. Treasury Department. The New National Era reported, “It is a compliment to the race that Miss Forten should be one of fifteen appointed out of five hundred applicants” (quoted in Sterling,1997:285). It was at the Treasury that she met her future husband.

Following her marriage to Francis Grimké in 1878, Forten Grimké stepped back from public life, though she continued to write poetry and essays for publication. The Grimké home at 1608 R Street NW in Washington D.C. [Image at right] served as a social and cultural center for Black intellectuals. Mary Maillard’s research has uncovered details of its well-appointed and tasteful interior: polished furniture, inspirational artwork, and tables laden with fine French china and sparkling silver cutlery (Maillard, 2017:7–9). In 1887, the Grimkés began hosting weekly salons where guests discussed a range of topics, from art to civil rights (Roberts, 2018:69). She also helped organized a group known as the “Booklovers,” a club for elite Black women to discuss cultural and social issues (Roberts, 2018:70). In 1896, though in poor health, Forten was one of the founding members of the National Association of Colored Women. Her Dupont Circle brick home was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Forten’s life in Salem, Massachusetts during the mid-1850s, compared with those of contemporary people of color, was relatively genteel. She read widely in such authors as Shakespeare, Chaucer, Milton, Phyllis Wheatley, Lord Byron, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, among others. She attended lectures in Salem and Boston, and especially enjoyed learning about countries like Great Britain, where slavery had already been abolished. Forten was fascinated by historical and scientific exhibits such as could be seen in Salem’s East India Marine Society and the Essex Institute. At the same time, she suffered deeply from the racial prejudice that was deeply woven into the culture of the United States.

Though more privileged than many, Forten intermittently suffered from economic deprivation. Once the Philadelphia Forten enterprises went bankrupt, her father was unable to offer her much financial support. These economic pressures could easily have been ameliorated by her white grandfather, James Cathcart Johnston (1792–1865), son of a North Carolina governor and senator, who remained living until she was twenty-eight years old. Forten’s grandmother, manumitted bondswoman Edith Wood, had been the mistress of this prominent wealthy white southern planter before her death in 1846 (Maillard 2013:267). Historian Mary Maillard details the extent of his wealth: “Johnston possessed a vast estate; he was described at his death in 1865 as ‘one of the wealthiest men in the South.’ His property, spanning four counties, was valued at several million dollars and ‘his immense possessions on the Roanoke river comprise[d] the richest lands in the country’” (Maillard 2013:267). Forten did not receive any portion of this extensive estate, since Johnston left all his wealth, including three plantations, to three friends. No speculation about her grandmother’s former lover or mention of Johnston appears in her journals or letters, but it seems probable that she was aware of the lineage on her mother’s side, since she was raised almost as a sister to Johnston’s youngest daughter, her aunt, Annie J. Webb, who sued Johnston’s estate for her inheritance. Even late in Forten Grimke’s life, and throughout her successful marriage, true economic security remained elusive (Maillard 2017:150–51).

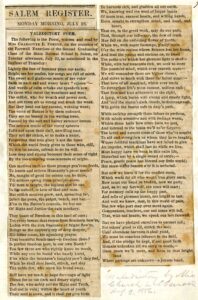

The final stanza of Charlotte Forten’s “Valedictory Poem,” [Image at right] written for the Farewell Exercises of the Second Graduating Class of Salem Normal School, and published in the Salem Register July 28, 1856, sums up her fierce dedication to the battle to end slavery and to the improvement of her society through reform. It also illustrates her unwavering Christian faith:

But we have pledged ourselves to earnest toil;

For others’ good to till, enrich the soil;

Until the abundant harvests it shall yield,

We must be ceaseless laborers in the field.

And, if the pledge be kept, if our good faith

Remain unbroken till we sleep in death,—

Once more we’ll meet, and form in that bright land

Where partings are unknown—a joyous band.

For forty years on her own, and for thirty-six years partnered with her husband, Forten Grimké strived to advance racial equality. The couple’s Washington, D.C. home was the setting for well-attended salons and meetings to help the causes they supported, such as racial and gender equality. Though Forten suffered greatly as an invalid during the last thirteen years of her life, the Grimké home remained a social and cultural center for activities to improve the lives of Black Americans (Sherman 1992:211). Charlotte Forten Grimké’s fifteen known poems, including the searing parody, “Red, White and Blue,” which turns her satirical eye on the hypocrisy of “Independence Day” celebrations in the United States, and as many essays appearing in leading periodicals from 1855–1890s were infused with her intense spirituality and deeply Christian consciousness. Charlotte Forten Grimké’s ground-breaking accomplishments as an educator, writer, and reformer, and her devoted work as the marriage partner of a Presbyterian minister, secure her place as an important figure in the realm of religion and spirituality.

IMAGES

Image #1: Charlotte Forten as a young scholar.

Image #2: The Story of Anthony Burns, Library of Congress pamphlet.

Image #3: Salem Normal School, Salem, Massachusetts.

Image #4: Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, commander of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment.

Image #5: Rev. Francis James Grimké, husband of Charlotte Forten.

Image #6: Charlotte Forten, circa 1870.

Image #7: The Charlotte Forten Grimké House, Washington, D.C., National Register of Historic Places.

Image #8: Charlotte Forten’s “Valedictory Poem” published in the Salem Register, 1856.

REFERENCES

Billington, Ray Allen. 1953. “Introduction.” Pp. 1-32 in The Journal of Charlotte Forten: A Free Negro in the Slave Era, edited by Ray Allen Billington. New York: The Dryden Press.

Cobb-Moore, Geneva. 1996. “When Meanings Meet: The Journals of Charlotte Forten Grimké.” Pp. 139-55 in Inscribing the Daily: Critical Essays on Women’s Diaries, edited by Suzanne L. Bunkers and Cynthia A. Huff. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Duran, Jane. 2011. “Charlotte Forten Grimké and the Construction of Blackness.” Philosophia Africana, 13:89–98.

Forten, Charlotte. 1953. The Journals of Charlotte Forten: A Free Negro in the Slave Era, edited by Ray Allen Billington. New York: The Dryden Press.

Forten, Charlotte. 1862. “Letter from St. Helena’s Island, Beaufort, S.C.” The Liberator, December.

Forten, Charlotte. 1858. “Parody on ‘The Red, White, and Blue.’” Salem State University performance by Samantha Searles. Accessed from www.salemstate.edu/charlotte-forten on 20 June 2021. Original manuscript in the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.

Forten, Charlotte. 1856. “Valedictory Poem.” Salem Register, July 28. Salem State University Archives, Salem, MA.

Forten, Charlotte. 1855. “Hymn, for the Occasion, by one of the Pupils, Miss Charlotte Forten.” Salem Register, July 16. Salem State University Archives, Salem, MA.

Glasgow, Kristen Hillaire. 2019. “Charlotte Forten: Coming of Age as a Radical Teenage Abolitionist, 1854–1856.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles. Accessed from https://escholarship.org/content/qt9ss7c7pk/qt9ss7c7pk_noSplash_041462aa2440500cfe2d36f1e412dd0f.pdf on 20 June 2021

Grimké, Angelina Weld. 2017. “To Keep the Memory of Charlotte Forten Grimke.” Manuscripts for the Grimke Book 2. Digital Howard. https://dh.howard.edu/ajc_grimke_manuscripts/2

Grimké, Charlotte Forten. 1988. The Journals of Charlotte Forten Grimké, edited by Brenda E. Stevenson, New York: Oxford University Press.

Maillard, Mary. 2013. “‘Faithfully Drawn from Real Life:’ Autobiographical Elements in Frank J. Webb’s The Garies and Their Friends.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 137:261–300.

Maillard, Mary, ed. 2017. Whispers of Cruel Wrongs: The Correspondence of Louisa Jacobs and Her Circle, 1879–1911. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Noel, Rebecca R. 2004. “Salem as the Nation’s Schoolhouse.” Pp. 129-62 in Salem: Place, Myth and Memory. Edited by Dane Morrison and Nancy Lusignan Schultz. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Roberts, Kim. 2018. A Literary Guide to Washington, D.C: Walking in the Footsteps of American Writers from Francis Scott Key to Zora Neale Hurston. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Rosemond, Gwendolyn, and Joan M. Maloney. 1988. “To Educate the Heart.” Sextant: The Journal of Salem State University 3:2–7.

Salenius, Sirpa. 2016. An Abolitionist Abroad: Sarah Parker Remond in Cosmopolitan Europe. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press.

Sherman, Joan R. 1992. African-American Poetry of the Nineteenth Century: An Anthology. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Sterling, Dorothy, ed. 1997. We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Stevenson, Brenda. 1988. “Introduction.” Pp. 3-55 in The Journals of Charlotte Forten Grimké, edited by Brenda Stevenson. New York: Oxford University Press.

Winch, Julie. 2002. A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten. New York: Oxford University Press.

Xavier, Silvia. 2005. “Engaging George Campbell’s Sympathy in the Rhetoric of Charlotte Forten and Ann Plato, African-American Women of the Antebellum North.” Rhetoric Review 24:438–56.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Braxton, Joanne. 1988. “Charlotte Forten Grimke and the Search for a Public Voice.” Pp. 254-71 in The Private Self: Theory and Practice of Women’s Autobiographical Writings, edited by Shari Benstock. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Long, Lisa A. 1999. “Charlotte Forten’s Civil War Journals and the Quest for ‘Genius, Beauty, and Deathless Fame.’” Legacy 16:37–48.

Stevenson, Brenda E. 2019. “Considering the War from Home and the Front: Charlotte Forten’s Civil War Diary Entries.”Pp. 171-00 in Civil War Writing: New Perspectives on Iconic Texts, edited by Gary W. Gallagher and Stephen Cushman. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Webb, Frank J. 1857. The Garies and Their Friends. London: Routledge.

Publication Date:

21 June 2021