JUDITH TYBERG TIMELINE

1902 (May 16): Tyberg was born at Point Loma, California.

1920: Tyberg began to study for a bachelor’s degree at Theosophical University, Point Loma, California.

1921: Tyberg officially joined the Theosophical Society headquartered at Point Loma, California.

1922–1934: Tyberg taught lower grades at the Raja Yoga School, Point Loma, California.

1929: Tyberg received a bachelor’s degree from Theosophical University.

1929–1943: Tyberg studied Sanskrit and Hindu literature with Gottfried de Purucker, a leader of the Theosophical Society at Point Loma.

1932: Tyberg received a Bachelor of Theosophy degree from Theosophical University.

1932–1935: Tyberg served as assistant principal, Raja Yoga School at Point Loma.

1934–1940: Tyberg taught high school at Raja Yoga School.

1934: Tyberg received a Master of Theosophy degree from Theosophical University.

1935: Tyberg received a Master’s degree from Theosophical University.

1935–1945: Tyberg served as Dean of Studies at Theosophical University.

1935–1936: Tyberg toured several European countries to boost Theosophical groups and their work, and she taught Sanskrit to those who were interested.

1937–1946: Tyberg contributed articles and book reviews to The Theosophical Forum, the monthly journal of ideas published by the Point Loma Theosophical community.

1940: Tyberg became Head of the Sanskrit and Oriental Division of the Theosophical University.

1940: Tyberg became member of the American Oriental Society.

1940: Tyberg published the first edition of Sanskrit Keys to the Wisdom Religion.

1944: Tyberg received a doctorate degree from Theosophical University.

1946: Tyberg resigned as Trustee of Theosophical University and left the Theosophical Society (now located in Covina, California) over a leadership dispute.

1946–1947: Tyberg lived independently of any organization in Los Angeles, California. She supported herself through book sales, speaking to groups, and teaching.

1947: Tyberg traveled to India to study at Banaras Hindu University.

1947 (August 15): Tyberg was present for the celebration of India’s Independence.

1947: Tyberg had her first darshan with Sri Aurobindo and Mirra Alfassa (the Mother) at their ashram in Pondicherry, India.

1949: Tyberg received a Master’s degree in Hindu Religion and Philosophy from Banaras Hindu University.

1950: Tyberg returned to the United States and gave public lectures.

1951: Tyberg became Professor of Indian Religion and Philosophy at the American Academy of Asian Studies, San Francisco, California.

1951: Tyberg published First Lessons in Sanskrit Grammar and Reading.

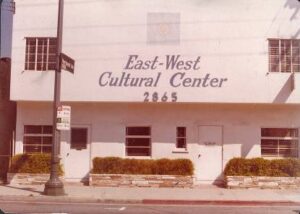

1953: Tyberg established the East-West Cultural Center in Los Angeles.

1953–1973: Tyberg founded the East-West Cultural Center School for gifted children, which operated for twenty years.

1970: Tyberg published The Language of the Gods: Sanskrit Keys to India’s Wisdom.

1973–1976: Tyberg taught courses on Sanskrit, Indian religion, philosophy and literature, and Sri Aurobindo’s thought, at the College (later University) of Oriental Studies in Los Angeles; she also served as Dean of Undergraduate School, College of Oriental Studies.

1976: Tyberg served as field faculty member for the Los Angeles branch of Goddard Graduate Program, Goddard College, Plainfield, Vermont.

1977: The East-West Cultural Center became debt-free. The Center subsequently became the Sri Aurobindo Center of Los Angeles and the East-West Cultural Center

1980 (October 3): Tyberg died in Los Angeles, California.

BIOGRAPHY

Judith Tyberg [Image at right] was a white American born at the Theosophical community of Point Loma (also called Lomaland), in San Diego, California. Her parents were Marjorie M. Somerville Tyberg from Ontario, Canada and Oluf Tyberg from Denmark. Not only were children raised at Point Loma, they were also educated there. Many Theosophists who came to live there were highly qualified to teach a variety of subjects at all grade levels, including mathematics, history, literature, and music. The only major area in the curriculum that Point Loma schools could not adequately staff were the sciences. Tyberg would have taken classes in all of these subjects, with her own  mother Marjorie Tyberg being one of the most active of the teachers. Theosophy was not taught to the children directly.[Image at right] Instead, they absorbed it in day-to-day conversations, community practices like meditation in the morning and before bedtime at night, and observing nature closely. At the time, the Point Loma peninsula was sparsely settled, and Point Loma pupils had some freedom in roaming about the area, as well as taking group trips into the interior of San Diego County. Many ex-students of Point Loma schools, when interviewed by this writer, looked back upon their educational years with fondness. Others had negative memories of Point Loma, because individual instructors and caregivers among the adults were not closely supervised and were responsible for mistreatment and abuse of children and adolescents, especially those who objected to community demands for conformity in thought and behavior. Tyberg did not seem to be among the disaffected, however. Quite the opposite: she embraced the ethos of Point Loma. As a young adult, she in turn taught younger children, and earned several degrees from the Theosophical University that the Point Loma community created to provide post-high school education for their college-aged youth. The leader who succeeded Tingley in 1929 was Gottfried de Purucker (1874–1942), a self-taught polymath who could work with several ancient languages and read widely during his years at the community. As the leader of Point Loma, he gave hundreds of lectures about all facets of Theosophy, which were transcribed and published in many volumes. Among his strengths was a facility with South Asian studies, and Tyberg became one of his star pupils in learning Sanskrit, the language of ancient Hindu scriptures.

mother Marjorie Tyberg being one of the most active of the teachers. Theosophy was not taught to the children directly.[Image at right] Instead, they absorbed it in day-to-day conversations, community practices like meditation in the morning and before bedtime at night, and observing nature closely. At the time, the Point Loma peninsula was sparsely settled, and Point Loma pupils had some freedom in roaming about the area, as well as taking group trips into the interior of San Diego County. Many ex-students of Point Loma schools, when interviewed by this writer, looked back upon their educational years with fondness. Others had negative memories of Point Loma, because individual instructors and caregivers among the adults were not closely supervised and were responsible for mistreatment and abuse of children and adolescents, especially those who objected to community demands for conformity in thought and behavior. Tyberg did not seem to be among the disaffected, however. Quite the opposite: she embraced the ethos of Point Loma. As a young adult, she in turn taught younger children, and earned several degrees from the Theosophical University that the Point Loma community created to provide post-high school education for their college-aged youth. The leader who succeeded Tingley in 1929 was Gottfried de Purucker (1874–1942), a self-taught polymath who could work with several ancient languages and read widely during his years at the community. As the leader of Point Loma, he gave hundreds of lectures about all facets of Theosophy, which were transcribed and published in many volumes. Among his strengths was a facility with South Asian studies, and Tyberg became one of his star pupils in learning Sanskrit, the language of ancient Hindu scriptures.

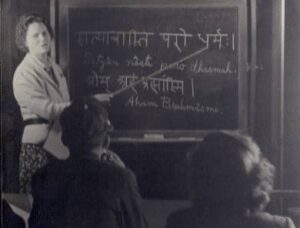

In the 1930s, [Image at right] when Tyberg was still a young woman, she journeyed to England, Wales, Germany, Sweden, and Holland to visit Theosophists. They saw Point Loma as the mothership of their movement. Many of them had lived at Point Loma. The purpose of Tyberg’s tour was to encourage these Theosophists, to lecture at their meetings, and to provide guidance on an individual basis.

During World War II, the Point Loma community relocated to a campus in Covina, California, in the Los Angeles area. When de Purucker died, a council took over leadership responsibilities. After the war, a Theosophist named Arthur Conger (1872–1951), a U.S. Army officer, was brought forward by some members of the community as the next leader, even though he had not resided at Point Loma. Others disagreed. Among them was Tyberg. An emotionally difficult period ensued, when lifelong members of the community contended with one another for the future of the movement by either supporting or rejecting Conger. Eventually the Conger advocates won, and Tyberg left the community, which had been home for her entire life.

From 1946 to 1947, Tyberg lived in the Los Angeles area, lecturing for fees on South Asian philosophy and literature, as well as Theosophy, to groups in peoples’ homes and various other locations. She also established a small bookstore in her residence. Had her life not made a radical turn toward India, it is likely she would have continued to live and work in Los Angeles and eventually find a steady source of income, probably through teaching. She had an earned Ph.D. in Sanskrit from Theosophical University. Sanskritists at mainstream universities would not have recognized this school as a legitimate educational institution of higher learning; nonetheless, Tyberg’s skills and breadth of knowledge in teaching Sanskrit were gradually becoming known among people in Southern California desirous of knowing more about India, Asia generally, and the languages of Asian religious texts.

Serendipitously, an opportunity presented itself for her to travel to India in 1947 and enroll at Banaras Hindu University in a Master’s degree program in Indian thought. It was still not common for American women to travel to Asia, particularly by themselves. Tyberg was a pioneer in this regard. Once in India, she made contact with a host of religious teachers, some from India, others from the United States or Europe. One of her philosophy instructors told her about Sri Aurobindo (1872–1950), a religious leader who lived in an ashram in Pondicherry (now Puducherry). Also living in the ashram was a European woman named Mirra Alfassa (1878–1973), whom devotees called the Mother. In the fall of 1947, Tyberg traveled from Benares (now Varanasi) to Pondicherry to have darshan (a spiritually-charged audience or encounter involving viewing the guru or deity figure and being seen by him or her) with these two spiritual figures. It transformed Tyberg’s life. She felt she had finally found her true spiritual home, and devoted the rest of her years to teaching the thought of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother.

After graduating from Banaras Hindu University, Tyberg returned to the United States. At first she taught at the American Academy of Asian Studies (AAAS) in San Francisco. At this time, there were few educational opportunities for Americans who wanted to pursue intensive study of Asian texts, philosophies, and practices. The AAAS attempted to rectify this. It included among its faculty Alan Watts (1915–1973), already a famous writer and speaker on Asian approaches to philosophical questions. But the school could not continue as it was (although a version of it exists today as the California Institute of Integral Studies), and Tyberg left. She went back to Los Angeles, where she had success in the past, and founded the East-West Cultural Center. Over the years the Center was located at several addresses. Today it is in a house in Culver City, California. Tyberg spent these years between the ages of fifty and seventy-eight (when she died) teaching gifted children, holding regular programs for the public about India and especially Sri Aurobindo’s thought, and providing all manner of spiritual celebrities from around the world a place to lecture and/or perform. The East-West Cultural Center became a node for a vast, international network of people who brought Asia to the West before the heyday of the 1960s. Tyberg also supported endeavors similar to her own. For example, the College of Oriental Studies (today called the University of Oriental Studies) tried to fill the gap that the AAAS had also tried to fill: providing advanced training in Asian languages and texts as well as fostering an appreciation for Asian contributions to world cultures.

As Tyberg aged, younger adults stepped in to help her run the Center. Her days were filled with teaching appointments (both groups and individuals), planning evening programming, and attending to the million worries that come with ownership of a house or building: maintaining the plumbing, seeing to electrical repairs, purchasing food as well as materials for building upkeep, and so on. When she died in 1980, her death certificate listed several medical problems that Tyberg had struggled with in her later years.

Tyberg did not try to build up a network of devotees who would then go out into the world to deliberately foster Sri Aurobindo’s teachings. Rather, this happened in an almost haphazard way, similar to the way that Point Loma Theosophists foresaw the spread of their own message. For Tyberg, coming to the insights of Sri Aurobindo was a deeply personal, individualized process. Those who were affected by this great Hindu teacher would then seek to realize his teachings in their own ways. In India, however, there was a more deliberate program of institution building based on the worldview of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother. This was the agrarian community of Auroville, which had great significance for followers around the world. It would provide the setting for a new breed of spiritual workers. Educational and agricultural experimentation went on there, as it still does today. Tyberg, like other devotees, supported Auroville, but did so by channeling individuals who would discover Sri Aurobindo first at the East-West Cultural Center, then later journey to Auroville. Among these were a handful of students at Chapman College (now Chapman University), who in the 1960s, like millions of other young adults, sought new ways to understand their place in the world by immersing themselves in Asian philosophies and spiritualities. They found their way to the East-West Cultural Center, then several of them later lived for various periods of time in Auroville.

Tyberg never sought public acclaim, which may help to explain why someone of her intellectual and spiritual caliber was quickly forgotten after she died. She had been a noted personality in Southern California, but aside from her modest Center she never established any institutions to carry on her work, and did not leave behind a corpus of texts outlining her worldview. Her greatest claim to publishing fame was the production in 1940 of Sanskrit Keys to the Wisdom Religion, a compilation of lessons for learning Sanskrit and getting a little dose of Theosophy mixed in. Many people who later became Sanskritists credited Tyberg with first enabling them to enter into study of the language through this book.

TEACHINGS/DOCTRINES

Judith Tyberg’s teachings and beliefs were grounded in both Theosophy and in the thought of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother.

Point Loma was started by Katherine Tingley (1847–1929), who was seen by followers as the Leader of the outward aspects of the community while Mahatmas (see below) were the spiritual guides of all members’ inward aspirations. Tingley persuaded middle- and upper-class Theosophists from the United States and Europe to relocate to Point Loma. They believed that Point Loma was something new in human history, a community that would train the coming generation of children [Image at right] to take their rightful place as spiritual leaders in the world. The childrearing practices that Tyberg would undoubtedly have been exposed to included self-discipline, personal and constant inspection of one’s motives, and living life according to higher purposes that had cosmic dimensions (Ashcraft 2002). Much of the child-rearing conformed to conventional ideas about how to raise children. Similar practices and motivations could be found in the homes of many middle-class families across the United States.

The Theosophical Society was founded in 1875 with Three Objectives:

To form a nucleus of the universal brotherhood of humanity, without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste or color.

To encourage the comparative study of religion, philosophy, and science.

To investigate unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in humanity (Theosophical Society in America [2021]).

These Three Objects served as the basis for all later developments in Theosophical worldviews. As the movement expanded from its initially small membership and diversified into several related movements, the three aspirations quoted here continued to sustain a certain unity across various organizations. Theosophists, no matter their organizational affiliation, also acknowledged the centrality of the writings of Helena P. Blavatsky (1831–1891). Blavatsky published a considerable body of work, but her most popular and highly regarded books were Isis Unveiled (1877) and The Secret Doctrine (1888). From all of these sources, then, the following summation of Theosophical ideas can be made.

All of reality is living and interconnected. Theosophists believe that even the tiniest cells in molecular structures are alive in some fundamental way.

All is evolving. Neither spirit nor matter remain the same, but evolve according to processes as eternal as the cosmos itself. Theosophists, taking their cue from Blavatsky, talked in terms of cycles: vast periods of time during which countless planets, stars, and species arise and fall, from the spiritual to the material, then back again. The key to appreciating this cyclical view lies in the direction of evolution: it is always toward greater coherence, vitality, compassion, and spirituality.

Humanity plays a key role in our own species’ progress. Human beings have existed in one form or another over countless generations, progressing always upward toward greater fulfillment.

Humanity has helpers, called Masters or Mahatmas. These entities have developed long past most of humanity’s present evolutionary state, defying the constrictions of time and space and taking on what appears as supernatural status. But in reality they have simply evolved according to timeless principles of spiritual advancement.

Humanity can also rely on the many religious and spiritual traditions in human history to point toward Theosophical truths. Although these truths are embedded in myths, legends, scriptures, and communities that outwardly seem to differ radically from one another, in reality, argue Theosophists, all religions and spiritualities strive toward the same eternal goal (Blavatsky 1877, 1880).

Sri Aurobindo wrote extensively when he moved to Pondicherry from Bengal in 1910 to live a semi-secluded lifestyle, supported by devotees who lived with him. He had received a western education and was also conversant in Indian texts. Thus his literary output in English was accessible to both western and Indian readers. The Frenchwoman Mirra Alfassa, or the Mother, joined Aurobindo later and became his partner in spiritual advancement. Many of her writings were based on remarks made to various individuals and answers given to questions posed by devotees. From these sources, we can posit the following ideas as being of central importance to an Aurobindonian worldview:

As with Theosophy, so here, the first basic belief is that all things are alive and interconnected. In the ancient Hindu texts called the Upanishads, this is called Brahman, the Absolute.

The world is alive with the Absolute, and upward bound in evolution toward greater consciousness.

Existing between the Absolute and humanity is the Supermind. It is not alien to human beings. Indeed, Sri Aurobindo argued that it appears in ancient Indian texts called the Vedas. It functions as a layer of truth and mind that enables human beings to evolve into higher species. Aurobindo argued that Supermind descends onto our earthly plane while we ascend to higher realms of spiritual awareness.

The individual devotee’s purpose is to realize the Supermind within themselves through acts of devotion (such as meditation) and good works.

More important than any other action they may take, the devotee surrenders to Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, perceived as divine and absolute in their own right.

The Mother references Shakti or the Great Goddess in various Hindu systems. Mirra Alfassa as the Mother embodies this divine power. She in effect becomes the Absolute. (Sri Aurobindo 1914)

One question that anyone who knows about Tyberg might legitimately raise is: how did she reconcile these two great systems in her life, Theosophy as the metaphysical basis for the first half of her life, Sri Aurobindo’s thought for the second half? Tyberg herself referred to this matter from time to time. She perceived Sri Aurobindo’s views as the fulfillment or completion of Theosophy. As noted above, both systems are non-dual and decidedly atheistic (according to a western conception of God). All things participate in Oneness. Both systems also posit a relationship between the world as it is and the world as it will be. Both use the metaphor of evolution to describe how this transformation from the now to the future will occur. Both also hallow advanced spiritual entities, the Theosophists with their Mahatmas or Masters, devotees of Sri Aurobindo with Sri Aurobindo himself as well as the Mother.

These resemblances are understandable. Theosophy borrows heavily from South Asian, especially Hindu, scriptures and teachings. So, too, did Sri Aurobindo rely on traditional Hindu texts like the Upanishads and Vedas. But there are divergences as well. Theosophy does not teach anything quite like the Supermind as Aurobindo described it. Although both systems see the cosmos as layered with spirit and matter, in Theosophy the upgrading of this world happens according to timeless cyclic processes, while Sri Aurobindo understood Supermind to be a projection of sorts from the Absolute onto this world.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The rituals and practices observed by Judith Tyberg fall into two distinct phases: the Theosophical and Aurobindonian.

The Theosophical Society, in crafting rituals, early on borrowed from Freemasonry, but by the time Tyberg was old enough to comprehend rituals at Point Loma it is questionable how much Masonic influence remained. What others of her generation reported were rituals designed to sustain inner piety and discipline: brief meditations practiced early in the morning and before retiring for the night, observing moments of silence, and integrating one’s inner convictions into daily routines. Point Loma Theosophists gathered for programs of cultural and spiritual enrichment: musical performances of the works of great western composers, and productions of ancient Greek as well as Shakespearean plays. They also observed the birthdays of important Theosophical leaders like Blavatsky and Tingley. And the community had programs marking holidays common in American society, such as the Fourth of July, Armistice Day, Easter, and Christmas (Ashcraft 2002).

At the East-West Cultural Center, [Image at right] Tyberg supervised a wide variety of programming. Public readings of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother would be followed by periods of meditation. Asian spiritual figures other than Sri Aurobindo and the Mother would make guest appearances at the Center, too. Yogi Bhajan (Harbhajan Singh Khalsa, 1929–2004) of Healthy, Happy, Holy Organization (3HO) fame gave some lectures and Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche (1939–1987) of Shambhala Buddhism. And Tyberg fostered interest in Hindu chanting, dance, and music. Performers traveling through or resident in the Los Angeles area found receptive audiences at the Center. These included dancers Indira Devi and Dilip Kumar Roy, and tabla master Zakhir Hussein (names found in interviews conducted by the author). Finally, important dates in the history of the Sri Aurobindo movement, such as the birthdays of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, were consistently observed each year (news items in Collaboration, a magazine for devotees of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother.

Much of Tyberg’s spirituality derived from reading and interpreting Hindu scriptures, and she fostered that spirituality among others, children as well as adults, through instruction in Sanskrit. She would teach people one-on-one, or in groups if there was interest. Using her own publications, she would guide the student through the basics of Sanskrit, and for those who wanted more in-depth study, she would tutor them as well.

It should be noted, [Image 7 at right] based on the above description, that ritual in Tyberg’s life was quietistic. That is, rather than ecstatic bodily motions related to possession, or even extensive liturgical observance requiring audience participation in the form of congregational singing and recitation, for Tyberg ritual performance was tied to meditative exercises, listening to texts being read aloud, discussion of ideas in those texts, and perhaps some chanting (see for example, “Jyotipriya – A Tribute” [2021]). This style of ritual, not unheard of in other contexts, pointed toward the spiritual priorities in Tyberg’s life: integration of one’s inner life, pulling together disparate parts of the self, and reflection on one’s motivations and emotions.

LEADERSHIP

The classical understanding of religious leadership is taken from the writings of German sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920), who argued for three kinds of authority: traditional, legal-rational, and charismatic. Traditional leaders rely upon long-term precedent. Their followers assume that traditional leaders have always ruled as they rule now. Legal authority is associated with the modern era, and in particular, bureaucracy. Legally defined leaders use reason to discern the needs of those they lead, then defer to bureaucracies to meet those needs. A third model of leadership, one that religious studies scholars have cited on numerous occasions, is charismatic authority. A charismatic leader has personal magnetism, and can inspire people to work together, or fight enemies together. Charismatic authority is socially constructed by followers who believe that the leader has received a “gift” of empowerment or authority from a higher source. In the study of new religious movements, charismatic leaders often are depicted as abusing and manipulating their followers. The leader is unethical, the followers easily misled (Gerth and Mills 1946:54).

It is true that charisma can be used for unpalatable ends by religious leaders, in both new religions and more established ones. Tyberg, however, does not fall into that category. She had personal charisma, but there is no indication in the sources available that she ever used her charisma to bolster her ego or compel people to act contrary to their conscience. Her charisma was manifested in her role as a teacher, which she believed herself to be: first, last, and always. For many years, beginning at Point Loma and later at the East-West Cultural Center, she led pupils in their lessons on many subjects, from the commonplace to the spiritual. In addition, her adult students came in all ages, and from all walks of life. She never seemed to reject anyone who had an earnest desire for greater spiritual insight.

The casual observer of Tyberg might conclude that she was too good to be true. She is like those whom American philosopher William James (1842–1910) called the healthy-minded in The Varieties of Religious Experience (1928). Such persons are happy and content with their spiritual state. They naturally put aside their own needs and wants for those of others. Suffering due to sin and chance alike is not within the register of their emotions. In all ways they seem naturally religious and are deeply satisfied with that state. They are contrasted by James with the “sick soul.” This is someone who grapples with sin and suffering in titanic struggles of inward despair. They are often melancholy or depressed. They cannot see the natural goodness all around them, and are jaded and wounded by their struggles (James 1928:78 ff.).

Tyberg was not a sick soul, to use James’s words. She was far more like the healthy-minded. In numerous interviews conducted with those who had first-hand knowledge of Tyberg, the overwhelming opinion was that Tyberg had the ability, coming from deep within her spiritual core, to focus her gaze upon the eternal. When the worries and cares of life became burdensome, she found ways to turn negatives into positives, as when she left the Point Loma Theosophical Society. She carried on her work in Sanskrit and South Asian philosophy by launching a career as an independent teacher, speaking in the homes of private citizens who invited her, and running a bookstore out of the house she was living in that specialized in titles about Hinduism, India, and South Asia generally.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Tyberg’s life was remarkably free of controversies as far as we know. Most people who came in contact with her liked and trusted her, especially if they were pupils in her classroom or spiritual nomads seeking greater enlightenment. Two incidents stand out, when Tyberg faced difficult ethical choices of a personal nature. Both of them are related to the Theosophical portion of her life.

The first occurred while she was a young woman still living at Point Loma. Tyberg was one of several women who acted as servers when Point Loma’s leader, Tingley, hosted individuals of some prominence at her residence for dinner. Tyberg relayed to her parents what was said at these dinners, and when Tingley heard this, she banned Tyberg from continuing as a server (Ashcraft 2002:85–87). Apparently Tingley thought that the conversations at these dinner parties were of a sensitive nature, and might impact either Tingley’s status and well-being, or the health of the Point Loma community, or both. But Tingley’s action had a severe impact on Tyberg. The latter had spent her life striving to be the model child and adult that her parents and other Point Loma residents wanted her to be. They expected their youth to exhibit Victorian values: sobriety, discretion, and courtesy. This may have been Tyberg’s first wrestling with cognitive dissonance. The woman she idolized, Katherine Tingley, had rejected Tyberg for behavior unbecoming a young Point Loma resident.

Eventually Tyberg was permitted to resume her role as a server. Only a few short years later, Tingley died in 1929 from injuries sustained in an automobile accident, and the famous dinner parties became things of the past.

The second controversy occurred some years later. When Point Loma leader Gottfried de Purucker died in 1942, a council of peers, mostly individuals who had been in his inner circle, directed the community until such time as a new leader would be revealed by the Mahatmas or Masters. Some in the community believed that the new leader was Colonel Arthur Conger, a military man who had not lived at Point Loma for very long. Technically, the issue that divided Theosophists was that Conger was made Outer Head of the Esoteric Section (ES). This meant that he was the earthly leader of the organization that was the heart of the Theosophical movement, an organization whose members knew secret information and insights not shared by most Theosophists. The Inner Heads were the Mahatmas or Masters, who were believed to guide Theosophists in making important decisions. Tyberg was among a group of ES members who did not think Conger was the legitimate Outer Head. In 1946, she left Covina. She was deeply disappointed and hurt that some of the people she had known all her life opposed her. She was also scandalized when, after she relocated to Los Angeles, she learned that she was accused of spreading false rumors about Conger. She wrote to him asking him to clear her name. Because the accusation included sexual innuendo, Tyberg was especially incensed that she would be associated with something so tawdry. But she rose above it, as she wrote to her mother, “The whole affair is like a shadow I’ve stepped out of into a light” (Judith Tyberg to Marjorie Tyberg, 10 Feb. 1947, Archive, East-West Cultural Center).

Did Tyberg’s experiences with factional strife at Covina sour her in some way? It is hard to know. The documentary evidence available does not show that. Perhaps, however, being so Victorian in her personal life, she did not share this dark period with just anyone, and if she did share it, that person must have been a trusted friend who would keep Tyberg’s thoughts in confidence.

If there is one overriding priority that Tyberg consistently fostered throughout her life, it was her desire to introduce the wisdom of India, and Asia in general, to westerners through exposure to Asian religious texts and their languages. Today we would call her approach “Orientalist,” meaning the western interpreter of an Asian text brings their own biases to that text. Orientalists tended to downplay Asian interpretations. One of the more famous instances of this tendency was the western presentation of the Buddha as an intellectual who taught a universal ethic of compassion and self-denial. This westernized Buddha was stripped of ritual importance, seeming to exist in suspended animation above the fray of actual Buddhist communities. In Tyberg’s case, her Orientalist penchant inherited from Blavatsky was to see Hindu scriptures as the basis for Theosophy. The title of the book that gave her notoriety as a Sanskritist, Sanskrit Keys to the Wisdom Religion, says it all. Sanskrit is not valuable in and of itself. Nor is it useful in shedding light on ancient Indian practice and thought. It is important, according to Tyberg, because it reveals the “Wisdom Religion,” that is, the timeless teachings of Theosophy. She even says in the Preface to this book that her hope is that when the reader learns Sanskrit terms, they will then progress onward to the Theosophical text of greatest importance, Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine (Tyberg 1940:vii).

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGIONS

Judith Tyberg conformed to a pattern, which emerged in the later nineteenth century and early twentieth century, of western women who embraced Asian spiritualities and cultures, and became public figures noted for that embrace of India. They included the second president of the parent Theosophical Society, author, and speaker Annie Besant (1847–1933), Margaret Elizabeth Noble/Sister Nivedita (1867–1911) of the Ramakrishna Movement, and the Mother herself of the Sri Aurobindo movement. These women pursued careers in India, whereas Tyberg went to India for inspiration and education but lived in the United States. But in important ways, Tyberg shared certain traits with these women. Like them, she was a westerner who took to South Asian spiritual movements as if coming to her true home. Like them, too, she was a public participant in such movements, through published writings, speeches, holding instructional sessions, and so on. Third, she was like them in rejecting fundamental ideas in the monotheistic traditions, such as the creator God of the universe, or the need to reconcile the reality of suffering with that God’s omnipotence and omniscience (see Jayawardena 1955, especially Parts III and IV).

Tyberg was a pioneer [Image at right] in the study of Sanskrit and ancient Hindu scriptures such as the Vedas. Up to that time, these areas had been almost exclusively male domains in western scholarship. In India, tradition held that only high-caste men could study Sanskrit texts. However, this did not stop de Purucker from training Tyberg, so that eventually she became a well-known and professionally recognized Sanskritist. Tyberg herself did not comment on the fact that she was a woman in a male-dominated field. For one thing, most women at that time were, like her, pioneers in professions previously closed to them. For another, it is very possible that, given the understanding of gender with which she was raised, Tyberg did not find gender categories to be important. In the Point Loma Theosophical tradition, which claimed to be continuous with the teachings of Helena P. Blavatsky, gender was somewhat malleable. Souls reincarnated as sometimes male and sometimes female. The gender binaries had essential traits, however, meaning that a soul incarnated in a given lifetime as a woman, for instance, would learn about the grand meaning of all things as a woman, with a woman’s supposedly innate sensibilities (Ashcraft 2002:116).

Although Judith Tyberg resembled other western women spiritual leaders of her time, she made a marked contribution to her era. The counterculture revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, which so transformed the landscape of western cultures, relied heavily on appropriation of Asian texts, ideas, and rituals. The revolution integrated disparate elements to form a major alternative worldview to that which had been generally accepted in the west. Before the hippies, before the rise of recreational drug use, before all these hallmarks of that moment in western history, Tyberg was steadily working away at her Los Angeles Center, making others aware of the rich heritage that South Asia had bequeathed to the world. Once the cultural revolution was in full swing, her East-West Center was a landmark on that revolution’s map. While her personal ethic did not approve of the excesses of the counterculture, Judith Tyberg stayed at her post until her death, providing instruction and inspiration to anyone who cared to listen.

IMAGES

Image # 1: Judith Tyberg, founder of East-West Cultural Center.

Image # 2: Children at Raja Yoga School in Lomaland, 1911. Photo from the Library of Congress, courtesy Wikimedia.

Image # 3: Judith Tyberg teaching sanskrit at the Theosophical University, 1943.

Image # 4: Judith Tyberg, age 20, in theatrical production at Lomaland, 1922.

Image # 5: Fourth location of the East-West Cultural Center, Los Angeles, 1963.

Image # 6: Anie Nunnally and Jyotipriya (Judith Tyberg), 1964. Nunnally is currently President of the East-West Cultural Center.

Image # 7: Judith Tyberg in her later years.

REFERENCES

Ashcraft, W. Michael. 2002. The Dawn of the New Cycle: Point Loma Theosophists and American Culture. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

Aurobindo, Sri. 1990. The Life Divine. Twin Lakes, WI: Lotus Press. Originally published serially in Arya beginning in 1914.

Blavatsky, Helena P. 1988. Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology. 2 Volumes. Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press. [Originally published 1877].

Blavatsky, Helena P. 1988. The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion, and Philosophy. 2 volumes. Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press. [Originally published 1888].

Gerth, H. H. and C. Wright Mills, eds. 1946. From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. New York: Oxford University Press.

James, William. 1928 The Varieties of Religious Experience. New York: Longmans, Green and Co.

Jayawardena, Kumari. 1995. The White Woman’s Other Burden: Western Women and South Asia during British Rule. London: Routledge.

“Jyotipriya – A Tribute.” 2021. Sri Aurobindo Center of Los Angeles and the East-West Cultural Center. Accessed from https://sriaurobindocenterla.wordpress.com/jyoti/ on 16 February 2021.

Theosophical Society in America. 2021. “Three Objects.” Accessed from https://www.theosophical.org/about/about-the-society on 16 February 2021.

Tyberg, Judith M. 1940. Sanskrit Keys to the Wisdom-Religion: An Exposition of the Philosophical and Religious Teachings Imbodied in the Sanskrit Terms Used in Theosophical and Occult Literature. Point Loma, CA: Theosophical University Press.

Tyberg, Judith M. 1947. Letter to Marjorie Tyberg. 10 February. Archive. Los Angeles: East-West Cultural Center.16

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Aurobindo, Sri. 1995. The Secret of the Veda. Pondicherry, India: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust. Originally published serially in Arya beginning in 1914.

Ellwood, Robert. 2006. “The Theosophical Society.” In Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America. Vol. 3, Metaphysical, New Age, and Neopagan Movements. Edited by Eugene V. Gallagher and W. Michael Ashcraft, 48–66. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2006.

Greenwalt, Emmett A. 1978. California Utopia: Point Loma: 1897–1942. rev. ed. San Diego: Point Loma Publications. Originally published 1955.

Harvey, Andrew. 1995. “Aurobindo and the Transformation of the Mother.” Chapter Four in The Return of the Mother, 115–54. Berkeley, CA: Frog Ltd.

Mandakini (Madeline Shaw). 1981. “Jyotipriya (Dr. Judith M. Tyberg) May 16, 1902–October 3, 1980.” Mother India (February): 92–97.

Mandakini (Madeline Shaw). 1981. “Jyotipriya (Dr. Judith M. Tyberg) May 16, 1902–October 3, 1980 II.” Mother India (March): 157–62.

Mandakini (Madeline Shaw). 1981. “Jyotipriya (Dr. Judith M. Tyberg) May 16, 1902–October 3, 1980 III.” Mother India (1981): 210–19.

Tyberg, Judith M. 1941. First Lessons in Sanskrit Grammar and Reading. Point Loma, CA: Theosophical University Press.

Tyberg, Judith M. 1970. The Language of the Gods: Sanskrit Keys to India’s Wisdom. Los Angeles: East-West Cultural Center.

Publication Date:

17 June 2021