VRATAS AND EVENTS AFFECTING WOMEN TIMELINE

1500 b.c.e. – ca. 1000 b.c.e.: The time period in which it is estimated by scholars that the Vedas, the oldest Sanskrit Hindu religious books, were composed. The most important of the four Vedic books is the Rigveda, the book of hymns to the gods. It also includes ritual practices such as vratas.

sixth century b.c.e. – ca. second century b.c.e.: The time period in which the major Upanishads, which come at the end of the Vedic corpus, were composed. They are commentaries on the earlier Vedic texts. They deal with meditation, philosophy, and metaphysical knowledge; some parts include mantras, blessings, rituals, and ceremonies such as vratas.

400 b.c.e. – ca. 200 b.c.e.: The time period in which the Mahabharata was composed. The Mahabharata (the Great Epic of the Bharata Dynasty) is a Sanskrit epic poem that is understood by most Hindus to be both historical and religious (giving rules for dharmic action). It is very long, with more than 100,000 couplets, and its authorship is attributed to the sage Vyasa. It includes much mythic and religious data, including stories that later became the basis for vratas, such as the story of Savitri.

third century c.e. – tenth century c.e.: The time period in which the earliest versions of the Puranas were composed. Later Puranas date from the twelfth to the sixteenth centuries (and there are some more modern Puranas). The word purana literally means “ancient” or “old,” and these texts exist in many versions. They are books of medieval Indian literature which include a wide range of topics, particularly myths, legends, and folklore. Many of the Puranas are named after major Hindu gods and goddesses such as Vishnu, Shiva, and Devi. There are eighteen Maha-puranas (Great Puranas) and eighteen Upapuranas (Minor Puranas), with more than 400,000 verses. The Puranas link the practice of vratas to the empowering concept of shakti, the feminine power of creation.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS THAT SHAPE THE ISSUE

Derived from the verbal root “vr” (to will, rule, restrain, conduct, choose, select), the word vrata is found over two hundred times in the Rigveda (Monier-Williams 1992/1899) in the Vedas, the oldest scriptures composed in Sanskrit in what came to be known as the Hindu tradition. It is difficult to find the historical origins of the oral traditions of vratas, but we may say that they have come to be a major ritual for women in villages and rural areas. Over time, the public focus of vratas shifted from priestly (brahmanical) ritual to local ritual, with older women teaching vratas to young girls, and fewer priests (brahmins) teaching them to boys. In some areas of South Asia, vratas have become an entirely female tradition. It is an ascetic practice for female householders.

Vrata means “the taking of a vow,” and it involves undergoing certain practices in order to achieve a desired aim. A vrata is a vow or promise, usually to a deity, associated with a ritual practice. It is generally performed in order to gain some goal—a happy family with many children, wealth, a job, or recovery from disease or disaster. While religious elements of austerity and purity often appear, its goal is not to detach the performer from the physical world, but rather to gain blessings and a desired worldly outcome. There are folk vratas handed down by oral tradition and performed in rural areas, and there are more formal vratas, which are based on classical Indian religious literature. While folk vratas are generally performed by girls and women, more brahmanical vratas may be performed by both men and women (Sen Gupta 1976: Appendix, Table 4.3).

Religious Studies scholar Mary McGee surveyed the meanings of the term vrata in Vedic literature and found that the word was used as a command, a religious duty, devotion to a particular deity, proper behavior, and religious commitment; and she notes the debates on the Sanskrit origins of the term (McGee 1987:16). In the Rigveda, thought by scholars to be the earliest Vedic text composed from approximately 1500 b.c.e. onwards, every person’s vocation is called their vrata, as in hymn 9.112.1. Thus, whatever profession one is dedicated to may be called their vrata in the Vedic literature. The performance of sacrifice can also be called a vrata, as in hymn 1.93.8 of the Rigveda. This is the earliest written source for vratas. The major Upanishads coming at the end of the Vedic corpus, composed approximately sixth century b.c.e. to second century b.c.e., describe the vrata as an ethical and behavioral discipline, where compassionate action is important: the needy are helped, the hungry are fed, the stranger is welcomed, and one studies religious knowledge. The vrata encourages moral behavior and brings order and balance to the universe.

The Mahabharata (the great Epic of the Bharata Dynasty), composed in Sanskrit between approximately 400 b.c.e. and 200 b.c.e., contains stories that subsequently became the basis of vratas, especially the story of Savitri, the devoted wife who saved her husband from Yama, the god of death.

The Puranas (“ancient,” “old”) are collections of accounts of gods and goddesses composed in Sanskrit. The Maha-Puranas (Great Puranas) were composed approximately from the third century c.e. to approximately the tenth century c.e. They state that both men and women can expiate their sins through the performance of vratas, and vratas are the second most discussed method of doing so in the Puranas (after pilgrimage to holy sites). Vratas are usually optional rituals, performed for special blessings from the Hindu deities. The earlier Vedic and dharmashastra texts (books on religious and moral action, clarifying duties and responsibilities) describing vratas had a greater priestly focus, while the later Puranas had less focus on priests and brahmanical ritual. The Puranas link the practice of vratas to the concept of shakti, the feminine power of creation, which promotes a sense of empowerment for women performing vratas since all women are considered to possess and express shakti in Hinduism. McGee calls vratas “the primary vehicle available to women for the recognized pursuit of religious duties and aims” (McGee 1987:16).

South Asian studies scholar Anne Mackenzie Pearson examined the sociology of vratas in Varanasi (formerly called Benares by the British), and noted that vratas are associated with auspiciousness and purity, with goals of improving individual lives, helping with problems, and expressing personal faith (Pearson 1996). They are often categorized as women’s sadhana, or spiritual practice. Vratas are also practiced to overcome suffering and adversity, neutralize the adverse effects of planets or evil forces, remove birth-related problems (doshas) in the natal horoscope, win the approval of an offended deity, overcome infertility, bear children, cleanse the mind and body, express regret as part of a penance, acquire spiritual power, help the ancestors in the  heavens, or a family member, or a child who is in distress. Some vratas are expiatory, which are meant to neutralize past sins and transgressions (prayaschitta).

heavens, or a family member, or a child who is in distress. Some vratas are expiatory, which are meant to neutralize past sins and transgressions (prayaschitta).

Today, a vrata usually involves fasting, following the moral and ritual lessons of a story (katha), creating artistic diagrams [Image at right] (alpana) on the ground, reciting special verses or mantras, and offering worship (puja) to an image, often an image made by the woman herself from simple materials commonly available in an Indian village home. Alpanas are termed alpona(s) in West Bengal. Designs with color are frequently known as rangoli. They are known as kolams in South India, chowk-poorna (chowkpurana) in Punjab, and by other names.

There are a wide variety of vratas, and today there are many collections of vratas in book form [Image at right] published in India. Vratas may be performed at morning, evening, or night, every day for a month, on particular days of the year, or for several years in succession. Locales may vary widely: on riverbanks, under trees, outside in courtyards, inside one’s house. They tend to be household rather than temple-oriented, though some more urban girls go to Shakta priests at temples for instruction (McDaniel 2003:31, 36).

We can describe two types, the Brahmanical vrata of the Vedas and shastras (Hindu holy books written in Sanskrit) and the folk tradition of popular vratas. There are some significant differences between shastric vratas of mainstream Hinduism, and the non-shastric vratas of folk Hinduism, which do not come from classical literature. In the shastric vratas, the vrata techniques are usually not original—they have already been learned and performed and are simply being retold and passed down to a new audience. For the non-shastric or folk vratas, the vratas are usually new revelations, coming directly from the deity involved, usually to help a person in trouble or to punish a wicked person. Many of these have a goddess appear to teach a lesson to a girl who is proud or ignorant.

A vrata may be learned from a mother or grandmother, a more distant female relative, a neighbor, or occasionally from a priest. [Image at right] Vratas and their associated artistic diagrams have also been occasional subjects of college courses, for instance at Vishvabharati University’s Kalabhavana school in Shantiniketan, West Bengal. The vrata is understood through a story (the vrata katha), which explains the history of the vrata and the reasons for performing it. Whether the ritual associated involves total fasting, avoiding certain foods or activities, or creating symbolic images, the story is the centerpiece of the event. Many of the vrata stories involve goddesses. A frequent theme is the accidental or deliberate offending of the goddess, who then comes down to take her revenge upon the evildoer. The story then shows how she is pacified and returns to a state of harmony with her disciples. As the tension is resolved in the story, so some conflict or problem may also be resolved in the daily lives of the women who perform the vratas.

Vratas are also a form of religious play—some informants said that they saw the performance of vratas as a game when they were young, and only realized their significance when they were older (McDaniel 2003:108). It is religious action that can be either serious or enjoyable, and those vratas with the worship of images (murtis) can be interpreted by young girls as playing with dolls, pretending to have a family, or worshipping powerful deities. The practices can involve play, or love, or faith, or worship, or even anger, depending on the individuals and the context.

The mild forms of asceticism (such as not eating hot food or not taking a bath for a day or sleeping on the floor) associated with some vratas can also be understood as a game rather than as a sacrifice. One female head of an ashram interviewed told of how she learned to enjoy such ascetic practice, because it showed that she could be strong, and was done in a community of people that she loved (McDaniel 1989:212). Religious behavior can thus be learned in the context of play, which makes young girls more interested in the practices.

In puranic sources, the power of the vrata practice is based on the concept of shakti, or the cosmic feminine power of creativity. Shakti may be understood as impersonal or personal. Impersonal shakti is the power within the universe, latent in all creation, as a part of the goddess who has created the universe. As personal power, shakti may be increased within the person by meditation and ascetic practice. Such shakti is the basis of the power of female ascetics: the yoginis, sannyasinis, sadhvis, matajis, and sadhikas of India. Among female  householders, shakti may also be increased by following dharmic rules, or moral rules, such as eating only pure foods, showing reverence and respect towards husband and family, and keeping a clean and orderly household. [Image at right] A perfect dharmic wife is sometimes called a pativrata (vowed to her lord/husband), and she is believed in the folk tradition to have a great deal of shakti. There are many miracle stories of such perfect wives who can make food cook itself, carry water without a pot, or be in two places at the same time. Her power, or shakti, is gained by her devotion to husband and his family. An example of the power of such a perfect wife is shown in the vrata story of Savitri, who brought her husband back from the dead. Brides contemplate Savitri as their ideal role model.

householders, shakti may also be increased by following dharmic rules, or moral rules, such as eating only pure foods, showing reverence and respect towards husband and family, and keeping a clean and orderly household. [Image at right] A perfect dharmic wife is sometimes called a pativrata (vowed to her lord/husband), and she is believed in the folk tradition to have a great deal of shakti. There are many miracle stories of such perfect wives who can make food cook itself, carry water without a pot, or be in two places at the same time. Her power, or shakti, is gained by her devotion to husband and his family. An example of the power of such a perfect wife is shown in the vrata story of Savitri, who brought her husband back from the dead. Brides contemplate Savitri as their ideal role model.

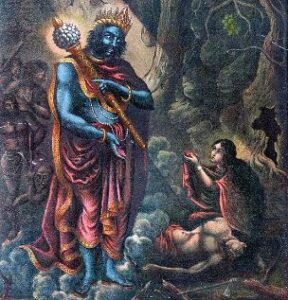

Savitri’s story is told in the Indian epic, the Mahabharata. It is thus a bramanical vrata, as it is based on a Hindu sacred text composed in Sanskrit. Savitri, daughter of King Ashvapati, chooses as her husband Satyavan, the noble son of a blind and  exiled king, who lives in a forest hermitage. Though warned by the sage Narada that the prince is fated to live for only one year more, she loves him and marries him anyway. After the wedding she leaves with her husband and goes to his father’s forest retreat. Here she lives happily until she becomes anxious about the approach of the fatal day. When it arrives, she follows her husband on his way to cut wood in the forest. He soon lies down exhausted at the foot of a banyan tree. Yama, the god of death, appears, and taking his soul, departs. [Image at right] Savitri follows him, and Yama grants her various wishes, anything except the life of her husband. However, she finally outwits him by wishing that she be the mother of one hundred sons, and Yama is forced to bring her husband back to life. Satyavan recovers and lives happily for many years with Savitri.

exiled king, who lives in a forest hermitage. Though warned by the sage Narada that the prince is fated to live for only one year more, she loves him and marries him anyway. After the wedding she leaves with her husband and goes to his father’s forest retreat. Here she lives happily until she becomes anxious about the approach of the fatal day. When it arrives, she follows her husband on his way to cut wood in the forest. He soon lies down exhausted at the foot of a banyan tree. Yama, the god of death, appears, and taking his soul, departs. [Image at right] Savitri follows him, and Yama grants her various wishes, anything except the life of her husband. However, she finally outwits him by wishing that she be the mother of one hundred sons, and Yama is forced to bring her husband back to life. Satyavan recovers and lives happily for many years with Savitri.

One vrata ritual based on this story is the Vata Savitri Vrata, a practice for married women. [Image at right] It sometimes has various regional practices added, but generally, it is performed on Vata Savitri Purnima (the full moon day) in the Hindu month of Jyestha (May-June). Women pray for long life of their husbands and they pray that they will never be widows. A local banyan tree (vata) is worshipped by the women, representing the tree under which Satyavan died. The women fast for three days, and then they break the fast when the vrata is over. The women (vratinis) wake up early in the morning and bathe and go to worship the banyan tree in different groups, wearing their best dresses and jewelry. Money and other gifts are given in a bamboo basket to brahmin men. Groups of women worship the banyan tree and listen to the story of Savitri. The women pray for good health for their husbands, and water the tree. They sprinkle red powder (kumkum) on it, and cotton threads are wrapped around the tree trunk, and then they walk seven  times clockwise around the tree. This is the parikrama or circumambulating the tree. [Image at right]

times clockwise around the tree. This is the parikrama or circumambulating the tree. [Image at right]

The ritual ends with the women giving each other gifts. This ritual commemorates the story of Savitri, and women hope to be as fortunate as she was. As it is a brahmanical ritual, brahmin priests (or men generally) get money and other gifts. They are often present for the ritual worship or puja. Rituals for the brahmanical vratas can be found widely in pamphlets across India.

The more rural forms of vrata have smaller groups of older women who act as teachers, and there is no necessity of brahmin priests or offerings to the brahmin men in town. Such vratas are similar to mainstream Hindu worship (puja) but oriented more towards the household than the temple. The oldest and most respected married woman (aye) is the vrata priestess of her household and of the group. Some folk vratas include Hindu deities, and some do not. The following are two short vratas which are performed on the holiday of Akshaya (“never-ending [success]”) Tritiya. They involve the worship of a living woman who is offered gifts and believed to bestow blessings.

The Ada-Holud brata, or the vrata of ginger and turmeric, is a Bengali folk vrata (or brata in Bengali). It is performed from the last day of the month of Chaitra (March-April), to the last day of the month of Baisakh (or Vaisakha, April-May) for a week each spring, and it should be continued for four years. It is the worship of fortunate wives, who are called ayes. Such women may be of any age but are often old. A woman whose husband is alive should be chosen, and she should be offered a handful of unhusked rice, and of coriander, as well as five pieces of ginger and five of fresh turmeric. She should also be offered sweets (sandesh, or small cheesecakes) and a small amount of money. The end of the fourth yearly brata is a time of celebration, and four auspicious wives should be invited. They should be feasted and given gifts. The original woman served should also be given iron bangles twisted with gold, and a fan, a sari, and a comb. The goal of this brata is to guarantee that the woman who performs it will never be a widow (Bhattacarya and Debi n.d.:25). Such reverence guarantees that the bratini will live a fortunate life, like the woman worshipped.

Other folk bratas in Bengal are dedicated to young girls. One is called the Akshaya-Kumari brata or the vrata to the young maiden, and it is to be performed every year for four years, on the Akshaya Tritiya day. On this day, the person performing the brata should invite a young girl to sit on a low wooden stool. The girl’s feet should be washed, and then painted with red alta paint. Then she should be wrapped in a sari with a red border, and her hair should be combed. The woman performing the brata should then paint dots of white sandalwood paste and vermilion powder on her forehead and feed her lavishly. This should be done once a year for four years. For the brata in the fourth year, the young girl and three other girls are to be invited for a good meal. They should be given saris with red borders, hairbrushes, combs, mirrors, and small gifts of money. The girl who was invited for the four consecutive years should receive more gifts. It is said that this vrata gives good fortune to both the girls and the women performing the vrata (Bhattacarya and Debi n.d.:33).

For the folk tradition, vratas tend to be direct revelations, while for mainstream Hinduism, they are only secondary sources, based on Sanskrit originals. This may be in order to emphasize that, for mainstream Hinduism, there are other texts that are more important revelations: the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Epics. However, the folk tradition does not depend on other texts, and vrata revelations are often direct descriptions of experiences, as opposed to texts handed down over time.

An example of a folk vrata from West Bengal that shows direct revelation is the brata of the pipal tree leaf (Asvatthapatar brata). According to the story or brata katha, long ago a wealthy girl named Lajjabati was proud of her status. She refused to sit beneath the local asvattha (pipal) tree because crows and ravens stayed in it. The tree was very hurt by her words, and it sighed silently. Soon the kingdom was invaded by robbers, and one night they stole Lajjabati’s gold jewelry. She wanted her jewelry back and she followed the thieves into the forest. She got lost and found herself before an asvattha tree in the woods. She asked it for shelter inside its trunk, and the tree miraculously opened and gave her shelter. S he stayed inside the tree, eating fruits and roots, until the goddess Durga passed by in the form of an old woman. [Image at right] She saw Lajjabati going in and out of the tree and asked her about this. Lajjabati started crying, saying she was lost, and Durga offered to show her the way home. However, Durga said that she would only do this if the girl paid for her pride by performing a special brata. She must perform this brata for four years to the asvattha tree, from the last day of the month of Chaitra to the last day of the month of Baisakh (about 30 days). She had insulted the tree, and she must atone for this. The goddess showed her the way home, and she returned to her parents, who were happy to see her again. Lajjabati performed the brata faithfully, and her family grew wealthy and she was married to a prince. She had many sons and daughters, and she lived happily with her family (Bhattacarya and Debi n.d.:9–11).

he stayed inside the tree, eating fruits and roots, until the goddess Durga passed by in the form of an old woman. [Image at right] She saw Lajjabati going in and out of the tree and asked her about this. Lajjabati started crying, saying she was lost, and Durga offered to show her the way home. However, Durga said that she would only do this if the girl paid for her pride by performing a special brata. She must perform this brata for four years to the asvattha tree, from the last day of the month of Chaitra to the last day of the month of Baisakh (about 30 days). She had insulted the tree, and she must atone for this. The goddess showed her the way home, and she returned to her parents, who were happy to see her again. Lajjabati performed the brata faithfully, and her family grew wealthy and she was married to a prince. She had many sons and daughters, and she lived happily with her family (Bhattacarya and Debi n.d.:9–11).

In this vrata, the goddess Durga came by, but only to reveal how the girl had hurt the tree’s feelings, and how she must make things right. The goddess revealed the vrata, both the story and the associated ritual, in order to help her and future women who might wish for blessings. Thus Durga gives a direct revelation of the vrata—it is not something that existed before her intervention. We may note that in Bengali Hindu folk religion, Durga is a forest goddess, called Vana Durga or Durga of the Woods.

Women who wish to follow Lajjabati and perform the vrata pick five types of leaves from the asvattha tree (budding, green, ripe, dry, and brittle) and hold them while immersing themselves in a lake or pond or river. The bratinis ask for blessings, and each leaf gives a different type of blessing. The leaves should then be placed in the water to float away, and the women should water the roots of an asvattha tree and pray before it, honoring the tree. The brata is usually performed in a group of girls or women, in the springtime. It is performed for four years in a row.

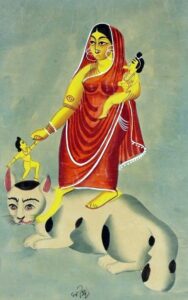

In another Bengali folk vrata,  the Jamaisashti brata, married women worship the local goddess who blesses pregnancy and children. [Image at right] They paint alpana designs on the ground and make an image of Shashthi and her cat out of dough to worship. According to the vrata story, a greedy wife would steal food, and blame it on the household cat. People in the house would beat the cat, so the cat complained to the goddess Shashthi, whose special animal (mount or vahana) was a cat. Following this, each time the woman gave birth to a child, the child disappeared.

the Jamaisashti brata, married women worship the local goddess who blesses pregnancy and children. [Image at right] They paint alpana designs on the ground and make an image of Shashthi and her cat out of dough to worship. According to the vrata story, a greedy wife would steal food, and blame it on the household cat. People in the house would beat the cat, so the cat complained to the goddess Shashthi, whose special animal (mount or vahana) was a cat. Following this, each time the woman gave birth to a child, the child disappeared.

After years of the infants disappearing, the woman stayed up at night, and saw Shashthi’s cat taking the baby into the woods. She followed it, and saw the goddess near a banyan tree, surrounded by children. She asked for her children back, and Shashthi said:

First ask forgiveness from the cat. You must accept your fault in order to get your children back. . . . Don’t ever beat my cat again or strike it with a broom or any other object. Don’t steal food and blame it on the cat. In every month of Jyestha [May-June], at this time, take a branch of a banyan tree, and make a model of a black cat out of dough. Then offer it dishes with every available fruit. During pregnancy, offer six pan leaves, six whole betel nuts, six kathali bananas, and six regular bananas. Then perform ritual worship to me. . . .

The woman came back with all of her children, and the household grew happy and wealthy. [Image at right] Other women followed her practice, and many people began to worship the goddess and gain her blessings (Bhattacarya and Debi N.d.:57–61). In this vrata story, the husbands also learn to worship Shashthi, along with their wives. This is unusual for rural vratas.

These vratas not only show the virtue of honesty and respect, but emphasize the value of nature, and how it is important to the goddess.

ORGANIZATIONAL ROLES PERFORMED BY WOMEN RELEVANT TO THE ISSUE

For folk vratas, it is usually the case that married women act as instructors, teaching girls from the age of five years onwards about the vrata rituals. [Image at right] At that age, the girl is taught to pluck flowers, dig pits for those vratas that require them, draw alpana pictures on the floor or entrance to the house, model small images to be worshipped, and learn mantras. Each vrata has its own alpana image—drawn with new clay whitened with powdered rice dissolved in water. Alpana diagrams give protection and/or fertility, and they may be accompanied by pictures which represent the desired goal or object. Some vratas include history—for instance, the Sejutibrata alpana represents the defeat of the ancient Dom rulers by invaders.

These vratas for girls have continued in traditional style for centuries. They were already an ancient tradition when Shib Chunder Bose wrote his Hindoos As They Are in 1881, in which he described the vrata rituals of the time. He stated that when a girl is five years old, she is initiated by an older woman into the vrata rituals, to get a good husband and happiness. She might begin with Shiva Puja, following the example of the goddess Durga (for Shiva is regarded as a model husband in many vrata stories, more faithful than the flirtatious god Krishna). She makes an earthen image, washes and sprinkles it with water, and prays while visualizing the form of the goddess. She then performs the vrata with flowers and sandal paste, and worships ten images of people and saints, and paints alpana designs on the floor (Bose 1881:35).

In her book, Memoirs of an Indian Woman, Shudha Mazumdar wrote about her childhood practice of vratas in Kolkata, West Bengal. She explained the reasons for it clearly:

Since much would be required of the girl when she attained womanhood, a system of education began to prepare her for her future life from her earliest days. As nearly all things in India hinge on religion, this training was also centered in religious thoughts and practices. It aimed at imparting an elementary knowledge of the basic ideas that were considered by a Bengali family to be good and true; it was accomplished through the medium of little rituals and prayers and fasts. These rituals had some connection with objects that were familiar to the child such as plant and animal life. By this system of training, the child was taught to be disciplined and dutiful and responsible. She who undertakes a lesson of this kind is said to have undertaken a brata. The literal meaning of brata is “vow.” So the child takes a vow to do a certain thing which must be performed (Mazumdar 1989:17).

She recalls some of her early practices, with simple Bengali mantras and without priests:

The tulsi brata teaches the child how to care for the bush of sweet basil that is so dearly cherished in every Hindu home. The cow brata makes her familiar with the four-footed friend whose milk not only sustained her in infancy but is still an important item of her daily food. There is another delightful brata called punyipukur, or the lake of merit, in which the child digs a diminutive lake and, seating herself before it, prays to Mother Earth for the gift of tolerance and for the fortitude to endure all things lightly, as does Mother Earth herself (Mazumdar 1989:17).

Many vratas include a reversal of traditional power relationships: figures who are weak, such as women, become strong and even saviors. People who make mistakes are forgiven, and they learn from their mistakes of pride and selfishness. Some vratas include helpful plants and animals which must be respected. Women are taught to be kind, and they are rewarded for compassion towards both human beings and towards nature.

THE ISSUES/CHALLENGES FOR WOMEN

There are two concerns that we may examine as issues for women. One is the role of men in the practice of vratas: Should brahmin priests (and brahmin men generally) be paid when it is the women who are performing the ritual? Another issue is raised by feminists: Do vratas contribute to female empowerment?

The issue of giving money and gifts to brahmin men on the occasion of women’s vratas has been debated. In the case of vratas in West Bengal, Pradyot Kumar Maity divides bratas into customary or primitive (“non-Aryan in origin”) and shastric (sacred texts written in Sanskrit). He believes that the shastric type of vrata, for which we have earlier literature, is really a later development with political overtones:

The sastric bratas, which are few in number, were created later on by the Brahmins who wanted to benefit out of those, either by participating in the priestly function or by taking an upper hand in society. . . . The origin of a sastric brata, out of the greed of the Brahmins who act as priests, may be illustrated if we see the method of observance of such a brata, for instance, the Harir-charan-brata. By observing this brata a bratini worships the feet of Lord Hari who is the protector of the Universe. A Brahmin priest officiates in this sastric brata and the bratini who observes this brata is to give a pair of gold or silver sandals . . . [and] one set of new clothes and dakshina (fee) in cash to the Brahmin priest (Maity 1988:3).

Maity contrasts this with the customary brata in which women conduct the rituals. There is no involvement of brahmin priests, and no gifts of gold or fees are required. He cites several other scholars who claim a non-Aryan origin to the bratas and argues that these bratas were later absorbed into brahmanical Hinduism. Traditional gifts for brahmin priests include cows (godana), bulls (vrishabha dana), land (bhoomi dana), house (griha dana), food (anna dana), agricultural tools (hala dana), and fruit (phala dana) (V [2020]).

Sudhir Ranjan Das describes the non-brahmanical nature of folk vratas. He emphasizes the importance of the folk or asastriya (non-shastric) vratas, the vratas that do not follow the Hindu religious books. He states of them:

Asastriya-vrata rites have no sanction in the sacred texts. These rites have been current amongst the people from indeterminable times. They are really folk rites preserving the remains of old traditions that go back to pre-historic ages. Asatriya-vrata rites are not merely childish and meaningless practices but they are replete with certain basic faiths and beliefs of primitive folk-life, translated into rituals that are observed for material benefits (Das 1953:12).

The shastric versus folk distinction in types of vrata (or brata in Bengali) has also been described by other authors who have written on the topic of vratas. Chittaranjan Ghosh in his Bangladeser Brata (Bangladeshi Vrata) as a contrast between pauranik (based in the Puranas) and laukika (based on folk tradition) bratas (cited in Maity 1988:6). Sankar Sen Gupta suggests a distinction between bratas as shastric (text-based and involving both genders) versus prachalita (women’s rituals) (Sen Gupta 1970:100). Some brata distinctions are based on participants: Abanindranath Tagore in his Banglar Brata (Bengali Vrata) categorizes three groups of bratas: shastric, nari, and kumari bratas (Sen Gupta 1970:100). The shastric group is performed by both genders. The nari bratas are those primarily performed by married women, and which focus on the health and happiness of husband and children. The kumari bratas are for unmarried girls, and they are intended to bring the girl a husband who is wealthy and wise. In West Bengal in India, most bratas are performed in groups of older and younger women, with the older women guiding the younger ones.

The Indian writer and cultural activist Pupul Jayakar speaks of vratas as a form of cultural resistance to brahmanical domination, named after the vratya ritualists and magicians of the Atharva Veda, one of the early Vedic texts noted for its magic spells. (The vratya ritualists were yogis who fell into trances, later described as wandering sorcerers who wore black robes and amulets). Jayakar describes vratas as mobile rituals independent of temples and specialists, which continued to be practiced during large movements of people, retreating from towns to forests and mountains during wars and famines, and during migrations from village to village. Performing vratas gave a sense of empowerment and an arena for creativity to women and other disenfranchised groups.

For the woman, as the main participant and actor of the ritual, the vratas were the umbilical cord which connected her to the furthermost limits of human memories, when woman as priestess and seer guarded the mysteries, the ways of the numinous female. It was around these vratas, thousands of variations of which existed in the cities, settled villages and forests, that the rural arts found significant expression. Free of the brahmanic canon which demanded discipline and conformity in art and ritual, the vrata tradition freed the participant from the inflexible hold of the great tradition. Unlike the brahmanic worship of mantra and sacrifice, which was available only to the Brahmin, the vrata puja and observances were open to the woman, to the non-Brahmin, to the Sudra and the tribesman. . . . Many urgencies mingled in the vrata rites, providing the channels through which contact with nature and life was maintained and renewed through the worship of the earth, sun, and water and the invoking of the energy of growing things, of trees, plants and animals (Jayakar 1990:15–16).

Some writers, such as Jayakar, Das, and Sudhansu Kumar Ray, see these vrata rituals as the remnants of older Indian religious systems, which were suppressed by the brahmanical orthodoxy. Ray theorizes that vratas were not only women’s religious activity, but in the past belonged to men as well:

Originally, brata was not a secluded domestic religion for women alone, as we see it today, but existed as an interior wing of a “single and complete magico-religious observance” that also had a powerful exterior wing for men. Somehow or other, the link between the two sexes has now been lost or cut off (Ray 1961:12).

He suggests that the men’s branch may survive in such village rituals as the gajan (involving painful ordeals and worship of the god Shiva) and the jhapan rites (religious dances involving snakes). Thus, an originally united religion became segregated by gender. This earlier religion has largely been destroyed—which he understands to be due primarily to the invasion of India by foreign cultures. He also blames brahmanical Hindu religion for shattering the vrata religion. However, the vratas have retained their informal importance for women.

The fundamental religion in which the Bengalis are “born and brought up” is called brata. It is a domestic form of religion and apparently not associated with temple service. Bratas are performed exclusively by womenfolk with a view to fulfilling their aspirations by means of magical rites. It can be performed by a single person, or by the “elders in assembly” of five married women (Ray 1961:10).

As we can see, there are arguments about the origins of vratas, and tensions between different types. But another area of tension can be the question of whether vratas are beneficial for women.

From a feminist perspective, the vrata tradition can be understood as being both helpful and harmful for women. It is good because it encourages female community and mutual respect for women of all ages and stations in life. By worshipping both young girls and old women, vratas demonstrate that both of these often-ignored groups have value and should be appreciated. Because the vrata tradition is a form of folk religion, it creates an alternative non-institutionalized hierarchy of women, ignoring the traditional hierarchy of male brahman priests in favor of informal, often low-caste priestesses, or the auspicious married women who become the teachers and ritual specialists of the tradition. It is primarily the women who pass down the stories and teach the practices in rural areas, not the men.

However, there are some aspects of the vratas that would be seen as negative from a feminist viewpoint. While some vratas tell women to disagree with their husbands and act independently, many stories reinforce traditional values, in which women are submissive, self-sacrificing, and obedient. Such values allow women to accept social situations in which they are often understood as second-class citizens, having less food and medical care than males, and fewer choices in life. Many young women in rural India grew up eating less food than their brothers, or even their leftovers, and they greatly resented this lack of respect for them. The brahmanical vratas reinforce these traditional values, instead of offering new options for respecting and caring for girls and women. The ideal woman as constructed by the brahmanical vratas sacrifices herself for husband and family, and there is little room for individual accomplishment and creativity. The ultimate goal of most of these vratas is for the girl to become a wife, and for the wife to bring good luck to her husband’s household.

WOMEN’S RESPONSES

We can see that vratas have acted to maintain an authoritative role for women within the folk religious tradition of Hindu worship, in a situation where most traditional religious leaders were male. Today, the urban practice of vratas is declining, at least partly due to the influences of both science and westernization. In West Bengal, the great challenge to the practice of vratas has been Communist materialism, which understands religious belief to be both superstitious and a threat to the state. In India as a whole, the rise of Hindu nationalism and political religion has lessened the importance of more local religious practices. However, in the villages, the folk traditions continue as they have for centuries, and the vratas still counter the male focus of political and religious power with their religious practice by groups of women of all ages.

We can also see that vratas have entered popular culture, and there are  online instructions for vratas, as well as computer-generated animation for them. [Image at right] This brings an ancient tradition into the modern world.

online instructions for vratas, as well as computer-generated animation for them. [Image at right] This brings an ancient tradition into the modern world.

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGIONS

We can note several benefits to girls and women from the performance of vratas that are linked to religious ideas and goals. Vratas encourage community and shared activity between women at different stages of life. There are vratas that include the ritual worship of young girls (kumari puja) as incarnations of the goddesses Durga or Lakshmi, and vratas that involve the ritual worship of older women, appreciating their luck in living happily and having a healthy family. The life stages of youth, motherhood and old age are shown respect through ritual worship and offerings (usually of food, red sindur powder and saris). The different stages of a woman’s life are shown to be valuable to the community, and group and individual friendships are supported. Such support is important, for much work in rural India is shared.

Vratas inspire artistic creativity, especially in the designing and painting of the alpana pictures which accompany vratas. [Image at right] These designs are unique to each artist, and young girls can get a reputation in the villages for the beauty, complexity, and originality of their alpana pictures. Artists can be appreciated without the necessity of expensive supplies and gallery shows, and modern events can be incorporated into the pictures. Such pictures can show the creation of religious worlds in physical form, as well as comment on the social world around the artists.

Vratas promote closeness to nature, as may be seen in stories of people who are rewarded for taking good care of plants and animals. Some vratas involve the creation of and caring for miniature forests, groves and lakes. Those who respect nature, watering tulsi plants and feeding hungry baby birds, get their dreams fulfilled. As in many European folktales, the compassionate hero or heroine who has pity on suffering plants and animals is blessed.

Vratas support showing concern for and caring for others, especially family members. Fasting and prayers are often performed for the sake of others, so that the husband and children may be healthy, or that they will have luck in the future, or gain wealth if they are poor. While some vratas are for the happiness of the woman performing them, most focus on the happiness of those around her, especially the men on whom her welfare depends. The ritual practices express clearly the concern of family members for each other. Performing vratas is a part of stridharma (wifely duty), a woman’s obligations in life.

Vratas foster concentration in girls who are often unschooled, and encourage positive expectations and optimism for the future. The various vratas of the ten wishes emphasize the future identity and situation of the vratini: she will be as strong as the goddess Durga, and patient as the earth. They may also bring encouragement, for the heroines and goddesses of the vrata stories suffer as human beings do, having to work at menial jobs and being despised and misunderstood, yet they are able to overcome their difficulties. Both deities and heroines within the vratas can act as role models for the vratinis.

Vratas articulate underlying power struggles, between husbands and wives, between co-wives, and between relatives of the extended family. Women can see that they are not alone, that their problems are shared by other women, and these problems can be portrayed in the context of the vratas. Vratas can “change one’s luck,” and also change the understanding of problems. For instance, several vratas reveal the hidden virtues of wives and daughters to the men in the family who might otherwise not notice them. Deities can be called down to bless the family, and to help with problems.

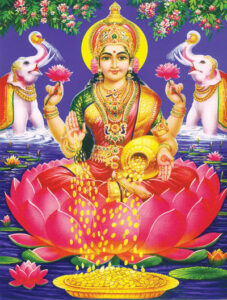

The influence of vratas on luck is important, because in traditional Hindu life, the woman is the luck of the house. [Image at right] When a new bride comes into a household, if everybody is healthy and there is extra food and money, the bride is said to be like Lakshmi and to bring good fortune with her. This makes her a valued member of the household. However, if she enters the house, and soon family members get sick, and the husband loses his job, then she is said to bring bad luck to the house and to be like Alakshmi, the goddess of poverty and misery. Her status in the household will then be low, for she will be blamed for the family’s misfortunes. Lakshmi is a major vrata goddess who brings good fortune to all.

It is difficult to guarantee luck, but vratas are believed to help in this area. By pleasing a deity, the woman may be blessed, and thus more likely to bring good fortune with her through life. Even if the vratas do not work, at least she can be seen as making an effort to bring good luck. If good fortune does occur, then the vratas (and the vratini) may be given credit for it.

IMAGES

Image #1: Woman and girls drawing an alpana in Rajasthan, India.

Image #2: Brihaspativar Vrath Katha booklet written in English published by Manoj Publications, Delhi.

Image #3: Woman drawing kolam.

Image #4: Digital Happy Savitri Vrata greeting in Oriya.

Image #5: Color lithograph from an album illustrating the story of Savitri’s defeat of Yama, the god of death, to save bring her husband back to life. Calcutta Art School, early twentieth century. British Museum. Wikimedia Commons.

Image #6: Vat Savitri Puja performed by married women so their husbands will live long, healthy lives.

Image #7: Vata Savitri Vrath. Women wrap thread around the banyan tree.

Image #8: Vana Durga, Durga of the Woods.

Image #9: Shashthi, ca. 1890. Wikimedia Commons.

Image #10: Digital greeting for Shashthi vrata.

Image #11: Mother and daughter performing a vrata.

Image #12: Lakshmi, goddess of wealth, good fortune, and fertility.

Image #13: Young women drawing a kolam.

Imagr #14: Lakshmi.

REFERENCES

Bhattacarya, Panditprabar Gopalcandra, and Rama Debi, eds. N.d. Meyeder Bratakatha, Baromaser. Calcutta: Nirmal Book Agency.

Bose, Shib Chunder. 1881. Hindoos As They Are. Calcutta: S. Newman and Company.

Chatterji, Tapon Mohan. 1965/1948. Alpona: Ritual Decoration in Bengal. Calcutta: Orient Longmans Ltd.

Das, Sudhir Ranjan. 1953. Folk Religion of Bengal: A Study of the Vrata Rites, Part 1. Calcutta: S. C. Kar.

Gangooly, Joguth Chunder. 1860. Life and Religion of the Hindoos, with a Sketch of my Life and Experience. London: Edward T. Whitfield.

Jayakar, Pupul. 1990. The Earth Mother: Legends, Ritual Arts, and Goddesses of India. San Francisco: Harper and Row.

Kane, Pandurang Vaman. 1958/1930. History of Dharmasastra: Ancient and Medieval Religious and Civil Law. vol. 5. Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute.

Maity, Pradyot Kumar. 1988. Folk Rituals of Eastern India. New Delhi: Abhinav Publishers.

Majumdar, Asutosh. 1991. Meyeder Bratakatha. Calcutta: Deb Sahitya Kutir Ltd.

Mazumdar, Shudha. 1989. Memoirs of an Indian Woman, ed. Geraldine Forbes. London, Me. E. Sharpe.

McGee, Mary. 1987. “Feasting and Fasting: The Vrata Tradition and Its Significance for Hindu Women.” Th.D. diss., Harvard University.

McDaniel, June. 2004. Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls: Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal. New York: Oxford University Press.

McDaniel, June. 2003. Making Virtuous Daughters and Wives: An Introduction to Women’s Brata Rituals in Bengali Folk Religion. Albany: State University of New York Press.

McDaniel, June. 1989. The Madness of the Saints: Ecstatic Religion in Bengal. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Monier Monier-Williams. 1992/1899. “Vrata.” In A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1042.

Pearson, Anne Mackenzie. 1996. “Because it Gives Me Peace of Mind”: Ritual Fasts in the Religious Lives of Hindu Women. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Ray, Sudhansu Kumar. 1961. The Ritual Art of the Bratas of Bengal. Calcutta: Firma KLM.

Sen Gupta, Sankar. 1976. Folklore of Bengal: A Projected Study. Calcutta: Indian Publications.

Sen Gupta, Sankar. 1970. A Study of the Women of Bengal. Calcutta: Indian Publications.

V, Jayaram. [2020.] “The Meaning and Significance of Vratas in Hinduism.” https://www.hinduwebsite.com/hinduism/concepts/vratas.asp. Accessed September 14.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Dutt, M. N. 2003. Vrata: Sacred Vows and Traditional Fasts. N.p.: Cosmo Publications.

Michaels, Axel. 2016. Homo Ritualis: Hindu Ritual and Its Significance for Ritual Theory. New York: University Press.

Wadley, Susan S. “Hindu Women’s Family and Household Rites in a North Indian Village.” In Unspoken Worlds: Women’s Religious Lives, 3rd ed., Nancy Auer Falk and Rita M. Gross, 103–13. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning, 2001.

Publication Date:

25 October 2020