SHINNYO-EN TIMELINE

1906: Itō Shinjō was born.

1912: Itō Tomoji was born.

1936: This year is the official foundation date of Shinnyo-en; Itō Shinjō began his clerical training at the Daigoji branch of Shingon Buddhism.

1936: Itō Shinjō and Tomoji’s eldest son Tomofumi (also called Chibun; born 1934, posthumous name Kyōdōin) died suddenly. After his death, he was believed to transfer people’s illnesses onto himself (bakku daiju)

1938: The temple Shinchōji was built in Tachikawa.

1942: Itō Shinjō and Tomoji’s daughter Masako was born, present leader of Shinnyo-en as Itō Shinsō.

1943: Itō Shinjō completed his Shingon Buddhist training at Daigoji and received the monastic consecration kontai ryōbu denbō kanjō.

1948: Makoto Kyōdan was founded.

1950: A former disciple accused Itō Shinjō of physical abuse. As a result of the trial, Shinjō was sentenced to a suspended three-year prison term (Makoto kyōdan jiken)

1951: The group’s name was changed to Shinnyo-en.

1952: Itō Shinjō and Tomoji’s son Yūichi (born 1937, posthumous name Shindōin) died from a bone degeneration disease in his hip joints. Like his brother, he was believed able to transfer people’s illnesses on to himself.

1953: Shinnyo-en acquired the legal status of a religious corporation.

1966: Shinnyo-en received and enshrined Buddha relics from the Buddhist temple Wat Paknam in Thailand.

1966: Itō Shinjō and Tomoji participated in the Japanese delegation to the Eighth International Congress of the World Fellowship of Buddhists held in Chiang Mai.

1967: On a tour through Europe, Itō Shinjō and Tomoji had a private audience with Pope Paul VI.

1967: Itō Tomoji died (posthumous name, Shōjushin’in).

1968: The new head temple Oyasono in Tachikawa was completed.

1971: The first training centre overseas was founded in Hawaii, followed in 1973 by the first overseas temple in Honolulu.

1989: Itō Shinjō died (posthumous name, Shinnyo Kyōshu Kongōshin’in) and was succeeded by his daughter Itō Shinsō (official title, Shinnyo Enshu).

1990: The Univers Foundation (Yuniberu Zaidan) was established, a non-profit foundation for the promotion of care for the elderly.

1991: The ITO Foundation for International Education Exchange (Itō Kokusai Kyōiku Kōryū Zaidan) was established. It is a non-profit foundation that promotes international students’ exchange by granting scholarships to Japanese students studying abroad and to overseas students studying in Japan.

1994: The Shinnyo-en Foundation was established. It is part of Shinnyo-en USA and supports educational programs in cooperation with community-based educational institutions.

1998: The Izumi Foundation, which provides medical help in developing countries, was established.

1999: The first Lantern Floating Ceremony in Hawaii took place.

2004: The Nā Lei Aloha Foundation in Hawaii, which among others organizes the Lantern Floating Ceremony, was established.

2006: The new temple Ōgen’in was completed in Tachikawa.

2006-2008: An exhibition of Itō Shinjō’s art, “The Vision and Art of Itō Shinjō,” was held in Japan, New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Milano, and Florence.

2012: The temple Yushin’in in Tokyo opened as a training centre and a place for academic and cultural events.

2013: An autumn equinox ritual was performed at St. Bartholomew in New York by Itō Shinsō, followed by a Lantern Floating Ceremony in Central Park the next day.

2013: Torikai Takashi (born 1953), deputy-director of the Department of Doctrinal Affairs, was announced to be Itō Shinsō’s successor designate.

2018: The public opening of the Hanzōmon Museum in Tokyo took place. There is a permanent display of Buddhist art owned by Shinnyo-en is complemented by special exhibitions of Buddhist art.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Shinnyo-en was founded by Itō Shinjō (1906-1989, original name Fumiaki) and his wife Tomoji (1912-1967) in 1936. The basis of their religious activities was Shinjō’s Shingon Buddhist training and ordination, as well as specific spiritual faculties deriving from the combination of Shinjō’s mastery in a divination technique called kōyōryū byōzeishō with Tomoji’s inheritance of the spiritual faculties of her aunt and grandmother. Shinjō had learned this orally transmitted, secret technique of divination from his father (Hubbard 1998:64). According to Jay Sakashita, it was based on the interpretation of lots; in the Itō family it often had been used during farm work to improve the crops (Sakashita 1998:35).

According to Itō Shinjō’s own account the group developed out of his counselling activities among co-workers based on his divination skills. These were fused with veneration of an image of the guardian deity Fudō Myōō the couple had installed at their home in 1935, and with Tomoji’s skills as a spirit medium. In 1936, they decided that Shinjō would give up his work in the aircraft company, Tachikawa Hikōki Kaisha, and that they would dedicate their lives to religious activities. The first organisation they established was called Risshōkaku, a religious association (kō) affiliated with the temple Naritasan Shinshōji. In addition, Shinjō engaged in studies on divination in order to deepen his understanding of the divination technique transmitted in his family (Itō 1997:345-58). At the same time he started his training to become a monk of the Shingonshū Daigojiha and subsequently accomplished the lay Buddhist consecration e-in kanjō (in 1939) as well as the monastic consecration kontai ryōbu denbō kanjō in 1943 (this date is given on the official website; according to Itō himself it was 1941 (1997:374)). Immediately afterwards, he adopted the Buddhist name Shinjō.  During that time, the number of Shinjō and Tomoji’s followers grew constantly. Due to their initiative, the temple Shinchōji was built in Tachikawa [Image at right] (nowadays called the “Founding Temple Shinchōji”), and they founded the Tachikawa Fudōson Kyōkai in 1938. This religious association was initially affiliated with the Daigoji branch of Shingon Buddhism until in 1945 the Itōs decided to dissolve this affiliation while maintaining their close relationship to this school of Buddhism. In the meantime, Tomoji had given birth to six children:

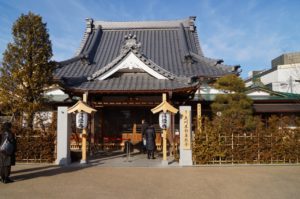

During that time, the number of Shinjō and Tomoji’s followers grew constantly. Due to their initiative, the temple Shinchōji was built in Tachikawa [Image at right] (nowadays called the “Founding Temple Shinchōji”), and they founded the Tachikawa Fudōson Kyōkai in 1938. This religious association was initially affiliated with the Daigoji branch of Shingon Buddhism until in 1945 the Itōs decided to dissolve this affiliation while maintaining their close relationship to this school of Buddhism. In the meantime, Tomoji had given birth to six children:

Her daughters Eiko (born 1933) and Atsuko (born 1940), the two sons Tomofumi (or Chibun; 1934-1936, posthumous name Kyōdōin) and Yūichi (1937-1952, posthumous name Shindōin) who came to play an important role as mediators to the spirit world and are objects of veneration up to the present day, and her third and fourth daughters Masako (born 1942, present head of Shinnyo-en, Buddhist name Shinsō) and Shizuko (born 1943, Buddhist name Shinrei) who were officially installed as successors to their father’s esoteric Buddhist lineage in 1983 (Itō 1997:363-70; Numata 1995:361-70). The eldest daughters Eiko and Atsuko are seldom mentioned in publications of Shinnyo-en. They turned their back to Shinnyo-en after a conflict within the family about the issue of Shinjō’s remarriage (Sakashita 1998:46-49).

In 1948, the name Tachikawa Fudōson Kyōkai was replaced by Makoto Kyōdan (official English translation: “Sangha of Truth,”) (Itō 2009:393). The group gained some negative publicity due to the so-called Makoto Kyōdan incident (Makoto Kyōdan jiken). In 1950, a former pupil of Itō Shinjō accused him of physical assault. The lawsuit, including an initial sentence and revision, lasted four years and ended with a three-year suspended sentence for Itō. In 1951, the group was renamed Shinnyo-en (“Garden of Thusness;” interpreted as “a garden open to all, where everyone can discover and develop their true Buddha nature,” Itō 2009:410), and in 1953 it was granted the status of religious corporation. With this change of name Shinjō adopted the title Kyōshu (“Master of the Teaching”), Tomoji that of Enshu (literally “Master of the Garden;” the title designates the administrative head of Shinnyo-en) (Itō 1997:391; Itō 2009:410). The term “Shinnyo-en” combines the fundamental Mahāyāna Buddhist concept of “thusness” (shinnyo, Skt. tathātā), i.e. the “true” nature of all phenomena beyond their immediate appearance, with the idea of a garden (en) that is accessible to anybody.

At about this time, Shinjō decided to make the sutra Daihatsu nehangyō (Skt. Mahāparinirvāna-sūtra, a text collection in forty volumes), i.e. the Sutra of the Great Nirvana, the authoritative scripture of his group; he officially introduced it to the believers (shinja) in 1956. By choosing a text that is less known in the esoteric Buddhist tradition, Itō Shinjō left the doctrinal path of Shingon Buddhism, thus emphasizing the uniqueness of his Buddhist teachings and training. This direction was further underlined by the replacement of Fudō Myōō as main object of veneration by Kuon Jōjū Shakamuni Nyorai, the dying Buddha teaching his last sermon as documented in the Sutra Daihatsu nehangyō (Akiba/Kawabata 2004:82f).When Shinnyo-en gained the legal status of a religious corporation in 1953, it had thus already developed its particular doctrinal outlook. Branch temples soon spread all over Japan and abroad: they were opened in Hawaii, the U.S. mainland, Taiwan, France, Italy, Belgium, Hongkong, Singapore and Germany (cf. Akiba/Kawabata 2004:180). After Shinjō’s death in 1989, his third daughter Shinsō inherited her mother’s title, Enshu-sama, and succeeded her father as head of Shinnyo-en. According to the annual statistics published by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Monbukagakushō), in 2017 the group had 931,141 members in Japan (Bunkachō 2018:671).

Ever since Itō Shinsō became the head of Shinnyo-en, she has increased the group’s engagement in welfare and educational activities, primarily by establishing a variety of foundations and by supporting cultural as well as educational institutions. In 1990, the year after Shinjō’s death, the Univers Foundation was established with the intention of promoting care for the elderly. It was followed in 1991 by the Ito Foundation for International Education Exchange (Itō Kokusai Kyōiku Kōryū Zaidan), which supports student exchange programmes for Japanese students going abroad as well as for overseas students studying in Japan (Itō Kokusai Kyōiku Kōryū Zaidansee; Ito Foundation for International Education Exchange). The Shinnyo-en Foundation was established in California in 1994 to support educational activities in cooperation with communal organizations and educational institutions in the US (Shinnyoen Foundation). After the Hanshin Earthquake in 1995, SeRV (Shinnyo-en Relief Volunteers) was founded as an organization of Shinnyo-en members engaging in volunteer relief work (SeRV Shinnyoen kyūen borantia sābu). In 1998, the Izumi Foundation started to provide medical support in developing countries (Izumi Foundation), followed in 2004 by the Nā Lei Aloha Foundation in Hawaii (Nā Lei Aloha Foundation), which organizes the Shinnyo Lantern Floating Hawai’i and supports community and charitable work in Hawaii. In addition, the group engages in silvicultural activities in a forest close to Ōme in Tokyo metropolis and provides scholarships for young photographers through the Kiyosato Photo Art Museum in the Yamanashi prefecture (Shinnyo – Shakai kōken katsudō; Shinnyo – Social Awareness in Shinnyo-en).

This engagement in educational and charitable activities was accompanied by the constant spread of Shinnyo-en temples overseas, beginning in 1971 with the first training centre established in Mililani, Hawaii (Akiba/Kawabata 2004:180). Nowadays, Shinnyo-en temples are to be found not only in all regions of Japan, but also in Asia (Taiwan, China, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand) and Australia, in Europe (France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, England), in the U.S. (California, New York, Washington, Illinois, Hawaii) and South America (Brazil) (Shinnyo – Shozaichi ichiran; Shinnyo – Connect). Itō Shinsō also actively engages in international activities, primarily by participating in interreligious or interfaith dialogue and in peace promoting events (such as a meeting on environment and healing initiated by the Global Peace Initiative of Women 2012 in Nairobi), and by performing the Shinnyo-en specific Lantern Floating Ceremony as well as the Fire and Water Ceremony (Saisho Homa) in various places all over the world, such as New York, Berlin, Paris, Saksaq Waman (Peru) and the Great Riff Valley in Kenya (Shinnyo – Shinnyo Fire and Water Ceremonies).

Beside these activities, Shinnyo-en is actively engaged in supporting academic research, especially research on Japanese religions. In Tachikawa, [Image at right] Shinnyo-en runs the Center for Information on Religion (CIR; Shūkyō jōhō sentā), an institution that fosters research on Buddhism and provides data on contemporary Japanese religions (Shūkyō Jōhō Sentā Center for Information on Religion). A more recent example is the USC (University of Southern California) Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture under the academic auspices of USC Dana and David Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences (USC Dornsife – Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture). The Center was founded in 2011 and re-named Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture after Shinnyo-en provided major funding in 2014. Its staff includes two professors specializing in the history of Japanese religions and literature respectively. In addition to fostering the study of Japan at USC and organizing workshops, conferences and lectures on Japanese religions, the Center supports various research projects.

Beside these activities, Shinnyo-en is actively engaged in supporting academic research, especially research on Japanese religions. In Tachikawa, [Image at right] Shinnyo-en runs the Center for Information on Religion (CIR; Shūkyō jōhō sentā), an institution that fosters research on Buddhism and provides data on contemporary Japanese religions (Shūkyō Jōhō Sentā Center for Information on Religion). A more recent example is the USC (University of Southern California) Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture under the academic auspices of USC Dana and David Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences (USC Dornsife – Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture). The Center was founded in 2011 and re-named Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture after Shinnyo-en provided major funding in 2014. Its staff includes two professors specializing in the history of Japanese religions and literature respectively. In addition to fostering the study of Japan at USC and organizing workshops, conferences and lectures on Japanese religions, the Center supports various research projects.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The scriptural foundation of Shinnyo-en is the Daihatsu nehangyō, i.e. the Sutra of the Great Nirvana. This sutra collection is said to contain the historical Buddha Shakyamuni’s (Skt. Śākyamuni) final sermon delivered just before his death. Itō Shinjō regards it as superior to any other sutra and doctrine, since it claims to comprise teachings on all Buddhas, even Buddha Amida (Skt. Amitābha) and Dainichi Nyorai (Skt. Mahāvairocana), the embodiment of the “dharma body” (hosshin) (International Affairs Department 1998:15f.; Itō 1997:50f). An introductory brochure describes the main contents of the Daihatsu nehangyō in the following way: (1) It emphasises the innate Buddha nature of every human being and concludes that everybody can attain liberation. (2) It points to the beginning- and endless existence of the dharma body of the Buddha. (3) According to the sutra there is a path to awakening even for bad people. (4) The sutra describes the state of awakening (satori) or nirvana in positive terms as being characterised by permanence, joy, self, and purity (see below) (jōraku gajō) (Budda saigo no oshie 2001:125; International Affairs Department 1998:33).

In addition, Itō points out that the sutra expounds the supernatural powers of those who have realised the state of nirvana (Itō 1997:175-82), thus providing a Buddhist frame of reference for the spiritual faculties transmitted and applied in Shinnyo-en. Due to these characteristics, the sutra gives Buddhist authorisation to Itō Shinjō’s religious agenda of offering an esoteric Buddhist path to salvation that does not require monastic life, and of realising it by means of the Shinnyo spirit world (shinnyo reikai) (International Affairs Department 1998:36).

The four characteristics of nirvana (nehan) as expounded in the sutra are further explained by Itō Shinjō: Nirvana is eternal (jō); it is a state of pleasure, namely the joy of being with Buddha (raku); there is a self, the self of nirvana, that enjoys being with Buddha (ga); one lives in the purity of nirvana (jō). Nirvana as the state of being awakened is described here as a joyful state that results from “becoming one with thusness” (shinnyo ni ichinyo suru), thus realising one’s inherent Buddha nature (Itō 1997:53, 41).

In addition to this rather theoretical understanding of Buddhist salvation, contemporary brochures and online texts emphasise the relevance of this concept for everyday life. Here, the joyfulness of nirvana as synonym for the state of being awakened is described as liberation from the hardships of our times: Jōraku gajō is said to counteract the feeling of uncertainty inherent to living in modern societies and to bring about the happiness of harmonious social relations. Its actualisation in everyday life can initiate a change of perspective; it requires permanent moral effort and leads to a self that is helpful to others. In this way, the positive understanding of nirvana as expressed in the sutra is fused with the Mahāyāna Buddhist ideal of selfless acting interpreted as the precondition of a happy life. The sutra thus authorises the propagation of an everyday ethics that is conveyed in more concrete terms in the practice sesshin shugyō. Yet, the sutra’s proclaimed role is to open the esoteric path to salvation to everybody by providing “an exoteric explanation for esoteric principles” (International Affairs Department 1998:36).

The other main attraction of the Daihatsu nehangyō for Itō Shinjō is its explanations about the supernatural powers of those Buddhas and bodhisattvas who have attained the state of nirvana, the so-called jinzū henge. Itō Shinjō is said to have achieved these powers due to his Shingon Buddhist training and integrated them into Shinnyo-en ritual and doctrine (Shinnyo-en Kyōgakubu 1983; “Shinnyo-en ni tsuite”). As a Mahāyāna Buddhist concept, these powers are said to be achieved by meditation and wisdom, such as the five supernatural powers of the sages and the six supernatural powers (rokutsū) of Buddhas and arhats, namely free activity, eyes capable of seeing everything, ears capable of hearing everything, insight into others, thinking, remembrance, and perfect freedom. They are manifested in the spiritual faculties that allow spirit mediums to connect to the Shinnyo spirit world and to reflect the practitioner’s mind during sesshin shugyō, the main practice of Shinnyo-en (see Itō 1997: 175-79; Hubbard 1998:76f).

In accordance with referring to the Daihatsu nehangyō as basic scripture, the main object of veneration in Shinnyo-en is the historical Buddha Shakyamuni, in particular the dying Buddha delivering his last sermon. He is called Kuon Jōjū Shakamuni Nyorai, the “Buddha Shakyamuni of eternal existence.” By combining the name and title of the historical Buddha with the epithets kuon (“eternity”) and jōjū (“permanence”), Itō Shinjō wanted to stress the eternal duration of Shakyamuni’s salvation work and existence in nirvana. In order to explain this eternal existence, he refers to the Sutra Daihatsu nehangyō and its assertion of the beginning- and endless dharma body as the real essence of Buddha (Itō 1997:43). Whereas in Japanese esoteric Buddhism the dharma body is personified in Dainichi Nyorai (Skt. Mahāvairocana), Itō Shinjō equates it with the “Buddha Shakyamuni of eternal existence.” He explains this difference to Shingon Buddhist thought by the fact that Dainichi Nyorai had never existed as a historical figure; instead he came into being only in the teachings of Shakyamuni. In fact, he claims, all Buddhas are comprised in Shakyamuni’s teachings. It is for that reason that Shinjō sculptured the dying Buddha (a huge sculpture is installed in the main hall of Shinnyo-en headquarters in Tachikawa) with Buddhas such as Amida or Dainichi inserted into the aureole behind Shakyamuni’s head (Itō 1997:41ff; Yasashii kyōgaku 2001:8).

Another doctrinal aspect stresses the relevance of the Itō family in addition to Shinnyoen’s Buddhist foundations. The concept of bakku daiju refers to the particular salvation work of the two deceased sons (Itō 1997:429-47). It is believed that the oldest son Tomofumi / Chibun (= Kyōdōin) opened the connection to the spirit world of ancestors when he died in 1936. When his brother Yūichi (= Shindōin) died in 1952, the two boys (ryōdōji) were believed to have joined their supernatural powers in order to relieve believers of their sufferings: Shindōin by “pulling [their sufferings] away” (bakku), Kyōdōin by taking them on himself instead (daiju) (Itō 1997:431-43). The two children are said to have established the so-called Shinnyo spirit world (shinnyo reikai); here, they mediate together with their parents between the believers and the ancestral spirit world as well as the world of Buddha (Itō 1997:442ff).

Thus the Itō family is established as the indispensable core of Shinnyo-en spirituality in two ways: [Image at right] by fusing their respective spiritual faculties and transmitting them on to others, Shinjō and Tomoji have founded a new spiritual lineage. Secondly, their deceased sons have established a connection to the spirit world on the basis of their spiritual powers, and the four of them together are said to maintain this connection.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Shinnyo-en offers a variety of monthly and annual rituals besides its main practice, sesshin shugyō. In English, they are designated as service, feast, or festival. Many of the regular rituals are similar to those offered in temples of ‘established’ Buddhism, especially those directed at the ancestors (such as ekō hōyō, urabon’e) or the equinox-related rituals. Others, however, are unique to Shinnyo-en and reflect the specific history and teachings of the group (such as the events to commemorate the founders). Shinnyo-en also performs funerals, yet members are encouraged to approach their respective family temple if possible. In addition, there is a wedding ceremony called the “Shinnyo wedding” in which the rites take place in front of a Buddha statue in a temple of Shinnyo-en. In addition, Itō Shinsō has engaged in performing huge rituals abroad that are adapted to local contexts and interpreted in a way that non-Buddhists can relate to, for example the Shinnyo Lantern Floating for Peace conducted in New York in 2015, or the Shinnyo Water and Fire Ceremonies conducted in Taipei. Kenya, Paris, Berlin, and New York, among  other places. (Shinnyo – Shinnyo Fire and Water Ceremonies).

other places. (Shinnyo – Shinnyo Fire and Water Ceremonies).

One of Shinnyo-en’s most famous rituals abroad, the Hawaii Lantern Floating Ceremony, [Image at right] includes hula dancers and is performed every year on the U.S. Memorial Day in Honolulu in order to remember and honour the deceased. Each year, thousands of people gather for this event, most of whom are not affiliated with Shinnyo-en (cf. Montrose 2018:158, 2014).

In the following overview on regular rituals, I use the English terms of the official website or official translations of the Japanese website. Whereas the English website lists only six annual festivals or services, the Japanese website lists nineteen (Shinnyo – Regular Services; Shinnyo – Hōyō Gyōji). Monthly rituals comprise a Merit Transfer Service in honour and support of the deceased, services to express gratitude to particular deities such as Benzaiten (Feast of Benzaiten) and Kasanori (Feast of Kasanori), services to commemorate Itō Shinjō’s death (Remembrance Service), or the death and attainment of nirvana of Buddha Shakyamuni (Feast of Eternal Bliss), and a fire burning purification ritual (Homa Service).

Many of the annual festivals or services relate to events or concepts specific to Shinnyo-en, such as the commemoration of the founders’ birthdays (Festival of the Ever-present, March 28, and Ōgen Festival, May 9), of the founding of the first temple (Festival of Oneness, November 3), or of the Shinnyo “spiritual faculties” (Service in Honor of the Shinnyo Spiritual Faculty, February 4). Others mirror widespread Buddhist annual rituals, such as the celebration of the New Year (New Year’s Service, January 1), the Setsubun Service to pray for good karma in the following year (February 3), the celebration of the birthday of Buddha Shakyamuni (Feast of the Buddha’s Birth, April 8), the Ullambana Service equating the o-bon rituals to welcome, entertain and support one’s ancestors (July 15), as well as spring and autumn equinox on the respective days in March and September. One of the main rituals is the Annual Training (formerly called Winter Training) in January, which commemorates the first winter training performed by Itō Shinjō and Tomoji in 1936.

Huge festivals include the esoteric Buddhist fire ritual (goma, in Shinnyo-en called Homa) and lantern floating, such as the Saito Homa Service at the beginning of October, i.e. the annual outdoor fire ritual. On August 16, many Shinnyo-en members gather at the lake Fuji Kawaguchiko at the foot of Mount Fuji to attend the Water Consolatory and Merit Transfer Service with Lantern Floating (mizusegaki ekō hōyō), i.e. a merit transfer service and lantern floating ritual on the waters of the lake when prayers are offered for ancestors and victims of disasters.

Beside these rituals Shinnyo-en offers a unique ritual practice developed by Itō Shinjō and Tomoji, the so-called sesshin shugyō. Although sesshin is a term used in Zen Buddhism to designate a meditation session, it is used here to indicate that the believer’s mind (shin) is touched (sessuru) by Buddha’s compassion (Itō 1997:186). The practice succeeds the so-called makoto shugyō, which had been practised in Makoto Kyōdan since 1948. Various types of sesshin shugyō are offered depending on the particular situation of the practitioner (see below). Spirit mediums (reinōsha; in Shinnyo-en they are called “spiritual guides”) have to master progressive stages of spiritual advancement in order to perform sesshin shugyō. During the ritual the mediums serve as mirrors believed to reflect the practitioners’ karmic situation back on the practitioners in order to open their eyes to karmic hindrances and subsequent ways of overcoming these. Hence the practice is intended to raise the practitioners’ spiritual state of mind as well as direct their moral conduct (Itō 1997:253-63).

In a regular sesshin shugyō, the kōjō sesshin, a group of people sit in a circle on the floor with their hands forming a hand gesture as if in meditation. They are faced by several spirit mediums who are immersed in concentration. After a while, the spirit mediums get attuned to language-related, visual, sensual or other forms of intuition that are interpreted as indications from the spirit world. They express these perceptions in so-called “spirit words” (reigen), and direct them to the practitioners to whom they are addressed. (cf. for example Numata 1995:388, Akiba/Kawabata 2004:2; Hirota 1991:27-40) The “spirit words” are believed to indicate karmic hindrances that are either caused by karmic ties to spirits of the deceased (be they relatives or not) or by moral deficiencies, such as habits, attitudes or behaviour that are judged as disguising one’s inherent Buddha nature. Often, the spirit words are rather abstract or vague phrases, so the practitioner has to relate them to certain situations or problems he or she is coping with. Examples of spirit words are:

Accept everything. Stop managing and don’t choose only what you like. By doing so you reduce the capacity of your heart and ultimately close it down. Don’t criticise others and talk about them behind their backs. Put yourself in your opposite’s place and convey the heart of sō-oya [Itō Shinjō and Tomoji, the “two parents”, M.S.] in a warm and friendly way.”, or “You are [only] grateful in front of people, but not when hidden in the shadow.”, or “Treat everything not as other people’s business but as your own business.” (Nagai 1991:106f.).

The ritual exercise itself is called “structured practice” (usōgyō) and is complemented by the “unstructured practice” (musōgyō) of applying what was indicated to one’s conduct in everyday life, thus purifying the acts of mind, mouth and body (Itō 1997:253). Three specific kinds of action, the so-called “three steps” (mitsu no ayumi), are encouraged among the believers: “joyous giving” (okangi), i.e. donations to the group; “helping others” (o-tasuke) by spreading the teachings of Shinnyo-en and recruiting new believers; and offering oneself in “service” (gohōshi), either by attendance in the temple or by cleaning public places. These three actions are regarded as a condensed form of the six virtues practised by a bodhisattva, the six pāramitā (Jap. ropparamitsu) (Yorokobi ni moete 2003:3; see also, Montrose 2018:155f). Due to this interpretation the believers are conceived of as progressing on the path of a bodhisattva, a development that will ultimately lead to the realisation of Buddhahood.

Today, there are five types of sesshin shugyō:

The regular sesshin is called kōjō sesshin. It is intended to enhance the practitioners’ awareness of their state of mind as well as of the appropriate conduct in everyday and religious life; consequently, the spirit words are rather general and abstract. The kōjō sōdan sesshin includes the aspect of consultation on problems arising from the spiritual progress. The sōdan sesshin and tokubetsu sōdan sesshin are meetings of the practitioner and the spirit medium only; they face each other in a separate room in order to cope with individual problems of the practitioner. An additional element is added in the kantei sesshin: here the divination technique transmitted by Itō Shinjō is applied to resolve problems that require a choice between several options (Akiba/Kawabata 2004:98). As is obvious from the strongly consultative character of the irregular sesshin, the practice does not only serve to mirror and improve someone’s karmic conditions, it is also a means of assisting believers in coping with the ups and downs of their lives.

How do believers themselves conceive sesshin shugyō, and where do they see the attraction of this practice? According to interviews with practitioners conducted in 2003 and 2004, the immediate consequence of sesshin shugyō to the practitioners is an impetus to moral and ritual action: it guides them in how to reflect upon and cultivate their behaviour and attitude, and they are encouraged to order offerings and merit transfer for suffering spirits if an ancestor or some other spirit has been identified as causing problems in the practitioner’s life. Thus, it has the double effect of providing immediate relief in harmful or problematic situations and of developing the practitioner’s morality and spirituality.

The practitioners I interviewed often described the moral effect of sesshin shugyō as a sudden shift in perspective that initiated an on-going process of self-cultivation. For example, a young believer and employee of Shinnyo-en told me how sesshin shugyō led to his change of consciousness when he was told to “become the other as much as possible.” He explained how these words opened up a new perspective on himself and the people around him by making him look at himself as child, as colleague, as brother etc. and include these perspectives into his self-perception. For him, this new view of himself affected his behaviour towards others so that he was able to establish more harmonious relations with the people surrounding him.

Another attraction clearly is the link to the invisible “spirit world” (reikai). In interviews and published testimonies believers often narrate how they experience a connection to the invisible world due to a suffering spirit who causes them physical (or other kinds of) trouble. For example, a female believer told me that her father had had a cough that would not disappear. In a sesshin, her brother was told about an ancestor who had died of a bronchial disease. He ordered offerings to this ancestor and their father recovered quickly. This story illustrates a typical pattern in which the actual suffering of a living person is interpreted as indicating a similar suffering of a deceased person and therefore necessitates a ritual solution. Another example is a female member who suffered from extreme shyness. When she heard that her deceased grandmother had had the same problem, she considered her as a companion in misfortune and felt greatly encouraged to overcome her shyness in order to relieve both of them of their burden.

This last example illustrates how sesshin shugyō is also perceived of as initiating and assisting a therapeutic process of coping with habitual behaviour that is felt to be a burden. It assists this process by providing the spiritual support a “secular” therapy cannot offer. For another, this last case also illustrates the concept of ken’yū ichinyo, i.e. the unity of this world and the world beyond. This unity ties the fate of the living irresolvably to that of the dead: the suffering of an ancestor or some other deceased is said to be reflected in the suffering of a living relative or someone who was in another way related to him/her (Akiba/Kawabata 2004:257). In this sense, sesshin is regarded as opening one’s eyes to the spiritual dimension of reality, to that which is invisible to our eyes yet influences and depends on our visible reality.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The present community is organized in analogy to family relationships resting on the principle of “guidance” (michibiki). On the most basic level, the person who introduces someone to Shinnyo-en is called the “guiding parent” (michibiki oya) of his or her “guided child” (michibiki no ko). The guiding parent is the person a new believer will ask for consultation on all questions related to Shinnyo-en (and often also on private issues). Based on the relation between guiding parent and guided child the community is divided into various units that form a hierarchical pyramid. The smallest of these units is the so-called suji (“lineage”). It is headed by the so-called “lineage parent,” i.e. the suji oya. A lineage consists of a net of guiding parents (plus their respective guiding parents) and their guided children (plus their own guided children), altogether between 100 and 1,000 households. Affiliation to a suji therefore depends on these “kinship ties” rather than on regional belonging; hence it is referred to as lineage among Shinnyo-en believers. About ten lineages form a bukai (division), and about five bukai make up a “group of divisions” (rengōbu) (Okuyama 2001:315f).

Among the regular activities within a lineage are the so-called “home meetings” (katei shūkai) that are organized by guiding parents and supervised by a parent of a suji. These are gatherings of believers during which the participants give testimonies of their faith, talk about problems and thoughts they are coping with and receive advice from their spiritual superiors. To many believers, these meetings fulfil a fundamental role in guiding them through the ups and downs of their lives. By sharing thoughts and problems, an atmosphere of solidarity is created that adds a lot to the social attraction of Shinnyo-en.

Up to the present, the leadership has been in the hands of the Itō family. However, during the Jōjūsai (Festival of the Ever-Present) in March 2013 Itō Shinsō announced that Torikai Takashi, deputy director of the Doctrinal Affairs Department, was assigned as her successor designate. Torikai (b. 1953), who received a Ph.D. from Tokyo University, joined Shinnyo-en in 1968 and started to work for the head temple in Tachikawa in 1981. Since then, he has successively held the positions of director of the Doctrinal Affairs Department (kyōgakubu), the International Affairs Department (kokusaibu), and the Ministry and Edification Department (fukyō dendōbumon). He also headed the Youth Association from 1990 to 1994. Beside his administrative positions, he is also a spirit medium and currently undergoes training for the Shinnyo-en transmission of the dharma stream, the Shinnyo Samaya Stream (shinnyo sanmaiya ryū) (Shinnyo – Kako no nyūsu).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Compared to other new religions, Shinnyo-en has not suffered from decreasing numbers of members but experienced an increase. The official religious statistics of the Agency of Cultural Affairs list for Japan 836,957 members in 2004, 909,603 members in 2013, and 931,141 members in 2017 (Bunkachō – Shūkyō nenkan).

After Itō Shinjō’s death in 1989, Itō Shinsō as the second leader of Shinnyo-en strongly contributed to the overseas expansion and international visibility of Shinnyo-en, be it in terms of establishing training centres and temples abroad, or in terms of performing huge ceremonies (for example in Taiwan, the U.S., Kenya, France, or Germany). She also engaged in international peace activities and charitable work by means of foundations and the organisation of voluntary relief work, for example in the aftermath of the triple disaster in March 2011. Shinnyo-en’s self-representation as an international religious community is also manifest on the group’s homepages. The Japanese website stresses Shinsō’s agenda to attract women and overseas members, whereas the English website presents Shinnyo-en as a transnational and contemporary form of Buddhism, or in its own terms “an international Buddhist community.” The English site does not mention most of the regular rituals performed in Japan, while adding a whole site on ritual activities overseas that does not exist on the Japanese website. Although Shinnyo-en is labelled “Shinnyo Buddhism” on the English site, its basic goals are phrased in general terms everybody can relate do, such as “peaceful coexistence and cooperation,” “philanthropic work,” or “contribution to the life of our planet.” In my view, Shinnyo-en in Japan still puts emphasis on its foundation in esoteric Japanese Buddhism, for example by its symbolic imagery (such as the sculpture of the dying Buddha, or statues of the Bodhisattva Kannon in the temples in Tachikawa) and the embedment of its ritual life in the well-known annual and life-cycle Buddhist rituals. In its representation to an international audience, however, the strong emphasis on commitment to world peace and inter-religious dialogue, to education, research and art, and to protection of the environment creates the image of a socially engaged Buddhism, not unlike Soka Gakkai International.

It is difficult to account for actual numbers of foreign members, since there is no standardised way of counting. For example, when asking the head of the Shinnyo-en temple in Munich in 2017, I was told that there were about twenty registered members of the Munich temple, but that more people were affiliated with this temple. For Germany, he estimated that among the approximately 2,000 members only 500 were actively involved.

The developments outlined here give rise to questions concerning the future leadership and the general character of Shinnyo-en in Japan. Will the overseas spread and activities of Shinnyo-en and the subsequent ritual adaptation to local and global cultures contribute to a gradual transformation of Shinnyo-en in Japan? Will its self-representation still emphasise its roots in thought and rituals of esoteric Japanese Buddhism and in widely spread customs of religious life in Japan? Or will modern and more global elements such as the propagation of individual self-enhancement and fulfilment, of sustainability, world peace etc. play a more prominent role? With the choice of Torikai Takashi as a high-ranking member of the organization who has no “traditional” Buddhist training or rank as successor designate the originally esoteric Buddhist foundations are clearly de-emphasized. He is introduced as a loyal member who has belonged to Shinnyo-en for a very long time, who is familiar with the main administrative offices and is presently undergoing further religious training. Thus, for the first time Shinnyo-en will be led by someone who is not a member of the Itō family, and leadership will not be based on religious charisma as it was ascribed to Shinjō, Tomoji and Shinsō. Given the fundamental role of the Itō family in the conceptualization of salvation, and the manifold ways in which it is interwoven into its devotional practice, it is hard to imagine how this change will affect the self-image and activities of Shinnyo-en in the future.

IMAGES

Image #1:Original Shinnyo-en building replica at Tachikawa.

Image #2: The temple Shinchōji built in Tachikawa.

Image #3: Buddha statue with busts of the Ito family.

Image #4: The Hawaii Lantern Floating Ceremony in 2018.

REFERENCES**

** Unless otherwise noted, this profile has drawn from my article “Shinnyo-en.” In: Birgit Staemmler, Ulrich Dehn (eds.), 2011. Establishing the Revolutionary. An Introduction to New Religions in Japan, Berlin: Lit Verlag, 181-99. For citation, please refer to the publication in Establishing the Revolutionary.

Akiba, Yutaka /Akira Kawabata. 2004. Reinō no riaritī e: Shakaigaku, Shinnyo-en ni hairu. Tokyo: Shinyōsha.

Bunkachō, ed. 2018. Shūkyō nenkan Heisei 29 nenban. Tokyo: Kyōsei.

Bunkachō – Shūkyō nenkan (Agency for Cultural Affairs – Religious Yearbook). Accessed from http://www.bunka.go.jp/tokei_hakusho_shuppan/hakusho_nenjihokokusho/shukyo_nenkan/index.html on 29 April 2019.

Hirota, Mio. 1991 [1990]. Ruporutāju Shinnyo-en: Sono gendaisei to kakushinsei o saguru. Tokyo: Chijinkan.

Hubbard, James. 1998. “Embarrassing Superstition, Doctrine, and the Study of New Religious Movements.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 66:59-92.

International Affairs Department of Shinnyo-en, ed. 1998. A Walk through the Garden: Shinnyo-en from Different Perspectives. Tokyo: International Affairs Department of Shinnyo-en.

Ito Foundation for International Education Exchange. Accessed from http://www2.itofound.or.jp on 29 April 2019.

Itō Kokusai Kyōiku Kōryū Zaidan. Accessed from http://www.itofound.or.jp on 29 April 2019.

Itō, Shinjō. 2009. The Path of Oneness. (English Revised Edition). Tokyo: International Affairs Department of Shinnyo-en.

Itō, Shinjō. [1957] 1997. Ichinyo no michi. Tokyo: Shinnyo-en Kyōgakubu.

Izumi Foundation. Accessed from http://izumi.org on 29 April 2019.

Montrose, Victoria Rose. 2018. “Shinnyoen.” Pp. 144-60 in Handbook of East Asian New Religious Movements, edited by Lukas Pokorny and Franz Winter. Leiden: Brill.

Nagai, Mikiko. 1991. “Shinnyo-en ni okeru reinō sōshō.” Tōkyō Daigaku Shūkyōgaku nenpō IX:101-15.

Nā Lei Aloha Foundation. Accessed from http://naleialoha.org on 29 April 2019.

Numata, Ken’ya. 1995. Shūkyō to kagaku no neoparadaimu: Shinshinshūkyō o chūshin toshite. Ōsaka: Sōgensha.

Okuyama, Michiaki. 2001. “Fukyō no keitai: Shinnyo-en.” Pp. 315-16 in Shinshūkyō jiten honbunhen.

Sakashita, Jay. 1998. Shinnyoen and the Transmission of Japanese New Religions Abroad. Ph.d. Dissertation, University of Stirling. Accessed from https://dspace.stir.ac.uk/handle/1893/2264#.XMbLoy1Xau5 on 15 April 2019.

SeRV Shinnyoen kyūen borantia sābu (Shinnyoen Relief Volunteer Service). Accessed from https://relief-volunteers.jp/about/profile.html on 29 April 2019.

Shinnyo – Connect. Accessed from https://www.shinnyoen.org/connect/ on 29 April 2019.

Shinnyo-en, ed. 2003. “Yorokobi ni moete innen o kiru.” Naigai Jihō 607: 3.

Shinnyo-en, ed. 2001a. Budda Saigo no Oshie. Shinnyoen: Nehangyō ni ikiru hitobito. Tokyo: Mainichi Shinbunsha.

Shinnyo-en, ed. 2001b. “Yasashii kyōgaku: denpō kanjō.” Naigai Jihō 595: 8.

Shinnyoen Foundation. Accessed from http://sef.org on 29 April 2019.

Shinnyo – Hōyō Gyōji (Services). Accessed from https://www.shinnyo-en.or.jp/services/on 29 April 2019.

Shinnyo – Kako no nyūsu (Past News) Jōjūsai – Enshu yori kyōdan jiki kōkeisha wo happyō (Festival of the Ever-Present: Enshu presents her successor designate)03.29. Accessed from https://www.shinnyo-en.or.jp/sp/news/2013/03/20130329.html on 29 April 2019.

Shinnyo-en Kyōgakubu, ed. 1983. “Shinnyo-en ni tsuite.” Asayū no otsutome. Tokyo: Shinnyo-en Sōhonbu.

Shinnyo – Shakai kōken katsudō (Social Contributions). Accessed from https://www.shinnyo-en.or.jp/activities/ on 29 April 2019.

Shinnyo – Regular Services. Accessed from https://www.shinnyoen.org/practices/regular-services.html on 29 April 2019.

Shinnyo – Shinnyo Fire and Water Ceremonies. Accessed from https://www.shinnyoen.org/practices/fire-water-ceremonies/about.html on 29 April 29.

Shinnyo – Shinnyo Fire and Water Ceremonies. Accessed from https://www.shinnyoen.org/practices/fire-water-ceremonies/index.html on 29 April 2019.

Shinnyo – Shozaichi ichiran (Locations). Accessed from https://www.shinnyo-en.or.jp/information/locations.html on 29 April 2019.

Shinnyo – Social Awareness in Shinnyo-en. Accessed from https://www.shinnyoen.org/social-awareness/ on 29 April 2019.

Shūkyō Jōhō Sentā Center for Information on Religion. Accessed from https://www.circam.jp/about/ on 29 April 2019.

USC Dornsife – Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Cultur Accessed from https://dornsife.usc.edu/cjrc/ on 29 April 2019.

Publication Date:

1 May 2019