SAINTS PERPETUA AND FELICITAS TIMELINE

Birth dates unknown.

203 c.e. (March): Perpetua and Felicitas were martyred in Carthage.

Both the year and the precise day that the women were martyred have sometimes been disputed. However, that they died on the birthday of Geta, the son of Roman emperor Septimius Severus, which has been calculated to have occurred in March, is generally accepted, as is the year 203 (Mursurillo 1972:xxvi–xxvii; Barnes 1968:521–25).

HISTORY/BIOGRAPHY

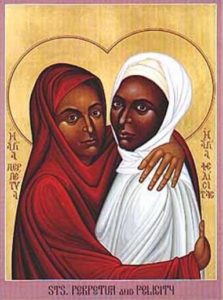

The text titled the “Passion of Saint Perpetua and Saint Felicitas and Their Companions” has been preserved in both Latin and Greek. The Greek version is generally thought to be a translation of the Latin text. [Image at right] The story is also told in a shorter version referred to as the “Acts of Perpetua and Felicitas,” or the Acta, which is most likely derived from the longer “Passion,” or Passio (Barnes 1968:521; Mursurillo 1972:xxvii; Halporn 1991:225). In English, the most commonly used translation is that of Herbert Mursurillo who, along with other scholars, draws on the critical edition produced in 1936 by C. J. M. J. van Beek. The account of Perpetua and her companions is unique in that a portion of the text purports to have been written by two of the martyrs themselves: Perpetua, who describes her terrifying ordeal while in prison, as well as four visions that she experienced prior to her death; and Saturus, another member of the same Christian community, who relates his own vision. That these sections of the text are actually first person accounts has sometimes been questioned, as has the identity of the anonymous narrator whom some have speculated may have been the late second/early third century North African church leader, Tertullian (Halporn 1991:224; Mursurillo 1972:xxvii; Barnes 1968:522; Shaw 1993:30).

Perpetua and her fellow Christians were martyred in Carthage, a vibrant and cosmopolitan provincial city in North Africa. [Image at right] Since conquering the area in the second century b.c.e., Rome had recolonized the city, making it the capital of the African provinces. Large building projects had been undertaken there and by the second century, Carthage had become a great and prosperous city, an intellectual center of the west, second only to Rome (Salisbury 1997:37–40). With its public forum, theater and vast array of available literature, Carthage drew in many persons, particularly wealthy persons, from other provincial towns. As historian Joyce Salisbury relates, one of those was the famous philosopher, Apuleius, who held Carthage in such high esteem that he once waxed poetically: “Carthage is the venerable instructress of our province, Carthage is the heavenly muse of Africa. Carthage is the fount whence all the Roman world draws draughts of inspiration” (Salisbury 1997:45). As a young, well-educated, wealthy Roman matron living in second-century Carthage, Perpetua would have been exposed to a rich diversity of languages, literature, religions, and ideas; one of which was a relatively new, but growing, religion wherein believers pledged themselves to none other than Jesus the Christ.

The “Passion of Saint Perpetua and Saint Felicitas and Their Companions” is divided into twenty-one sections with the narrator supplying the beginning and the end portions (sections 1–2 and 14–21) while sections 3–10 consist of Perpetua’s firsthand account; and 11–13 that of Saturus. According to the narrator, several young catechumens were arrested. Among this group were Vibia Perpetua, “a newly married woman of good family and upbringing” who was about twenty-two years old and who had an infant son; and several household slaves, one of whom was  another young woman, Felicitas, [Image at right] who was eight months pregnant (§ 2 and 15, Mursurillo 1972:109, 123).

another young woman, Felicitas, [Image at right] who was eight months pregnant (§ 2 and 15, Mursurillo 1972:109, 123).

Perpetua’s words provide insight regarding details of the arrest, and her time in prison, as well as into her familial relationships, especially her role as daughter and as mother. At one point, we learn that she is allowed to keep her nursing baby with her in prison. However, after she repeatedly refuses to renounce Christ and to sacrifice to the pagan gods, her father refuses to hand the child back to her care. The great strain that these events place on the entire family is evident in the four confrontations she has with her father. Early on, Perpetua relates that he is so angered by her insistence on being called a “Christian” that “he moved towards me as if he would pluck my eyes out” (§ 3, Mursurillo 1972:109). At another point, he begs her to have pity on the entire family — “You will destroy all of us!” (§ 5, Mursurillo 1972:113). Later, he appeals to her motherly sensibilities by imploring her to have pity on her baby; and always he is presented as a tormented old man filled with sorrow and even subjected to physical abuse by authorities, all on account of his wayward daughter.

Apart from circumstantial information related to her arrest, Perpetua’s own words also disclose the inner workings of her mind as she recalls four separate visions that reveal her impending doom in this life, yet also promise a more glorious life to come in Christ. With the telling of her very first vision, readers begin to understand the deep, close connection that Perpetua has with Christ with whom she will soon be joined completely. At the urging of her brother, who had also been arrested with the group, she agreed to pray for a vision that would help her discover whether she was “to be condemned or freed” (§ 4, Mursurillo 1972:111). After doing so, she experienced a vision of a bronze ladder reaching all the way to the heavens. Attached to the ladder were all manner of “metal weapons”—“swords, spears, hooks, daggers, and spikes; so that if anyone tried to climb up carelessly or without paying attention, he would be mangled . . .” while at the foot of the ladder a fierce dragon awaited to devour any who might dare to climb (§ 4, Mursurillo 1972:111). Yet, at the top of the ladder, she saw her fellow prisoner, Saturus, who waited for her and urged her to climb up to join him. This she managed to do but only after first trodding on the head of the dragon; after which she found herself in a beautiful garden being welcomed by an old shepherd with the words “I am glad you have come, my child” (§ 4, Mursurillo 1972:111). Recounting this vision to her brother the following day, Perpetua reveals that which she and Saturus now understood regarding their own futures: “We realized that we would have to suffer, and that from now on we would no longer have any hope in this life” (§ 4, Mursurillo 1972:112).

Perpetua’s ultimate triumph in spite of immense suffering was shown to her in a fourth and final vision [Image at right] experienced the day before the prisoners were sent into the arena. In this vision, she finds herself facing, not beasts, but rather an Egyptian “of vicious appearance, together with his seconds, [who had come] to fight me” (§10, Mursurillo 1972:119). The scene is one of gladiatorial combat as Perpetua, the young woman, becomes a man; not just any man, but rather, one strong and powerful enough to heap multiple blows onto her opponent and wrestle him toward the ground, where he “fell flat on his face” as she then stepped victoriously on his head (§ 10, Mursurillo 1972:119). It is following this vision that Perpetua writes, “I realized that it was not with wild animals that I would fight but with the Devil, but I knew that I would win the victory” (§ 10, Mursurillo 1972:119).

While the first and fourth visions reveal Perpetua’s triumphal victory in Christ, the second and third focus on the power of Christ that can be accessed through prayer. Perpetua relates that in a vision, she saw her younger brother, Dinocrates, who had died at the age of seven with a disease that she refers to as “cancer of the face” (§ 7, Mursurillo 1972:115). In this vision, she sees the young boy suffering terribly. With the cancer still visible, she watches him drag himself out of a dark hole toward a pool of water. Miserable, dirty, hot and thirsty, he attempts to reach the water but is unable to do so. Extremely upset by this vision, and yet confident in prayer, Perpetua says that she prayed day and night for her brother and was not disappointed; for yet another vision was given to her wherein she knew that her prayer had been efficacious. No longer suffering, Dinocrates appeared once again; but this time, clean and refreshed with only a scar where the cancer had once ravaged his face. Furthermore, water was now within his reach and he drank freely from a never-ending supply.

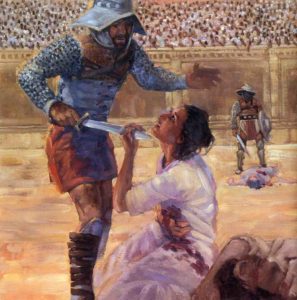

Through this re-telling of her own experience, and particularly her visions, Perpetua’s words gradually reveal her transformation from Roman matron to Christian martyr. [Image at right] Yet, the final movement toward one-ness in Christ is left to the narrator who records Perpetua’s ordeal in the arena and death, as well as her last days in prison where her “perseverance and nobility of soul” drew even the head of the jail to become a Christian (§ 16, Mursurillo 1972:125). It is also in this narration where the reader learns more about the other remarkable woman arrested from the Vibia family household, that is, the slave woman, Felicitas. According to this anonymous source, Felicitas was eight months pregnant at the time of the arrest. Yet, because Roman law forbade the execution of a pregnant woman, she feared she would be kept alive longer than the others and would have to suffer martyrdom alone. As it was, after fervent prayer by the group on her behalf, she gave birth quickly and thus was cleared to die along with  her comrades. While the text provides a gripping account of the deaths of all of the martyrs, it is the story of these two women, Perpetua and Felicitas, that most captures one’s attention. [Image at right] While all of the captives are stripped naked and paraded into the arena, the narrator focuses on the women as he reports that “the crowd was horrified when they saw that one was a delicate young girl and the other was a woman fresh from childbirth with the milk still dripping from her breasts” (§ 20, Mursurillo 1972:129). Still, the horror of the crowd apparently did not evoke sympathy, for after having been thrown about by a “mad heifer,” a beast especially chosen so “that their sex might be matched” with it (§ 20, Mursurillo 1972:129), the women, still alive, were led away with the others to ultimately die by a sword to the throat. Even so, according to the narrator, it was the noble Perpetua herself who controlled the outcome, as she “took the hand of the trembling gladiator and guided it to her [own] throat” (§ 21, Mursurillo 1972:131).

her comrades. While the text provides a gripping account of the deaths of all of the martyrs, it is the story of these two women, Perpetua and Felicitas, that most captures one’s attention. [Image at right] While all of the captives are stripped naked and paraded into the arena, the narrator focuses on the women as he reports that “the crowd was horrified when they saw that one was a delicate young girl and the other was a woman fresh from childbirth with the milk still dripping from her breasts” (§ 20, Mursurillo 1972:129). Still, the horror of the crowd apparently did not evoke sympathy, for after having been thrown about by a “mad heifer,” a beast especially chosen so “that their sex might be matched” with it (§ 20, Mursurillo 1972:129), the women, still alive, were led away with the others to ultimately die by a sword to the throat. Even so, according to the narrator, it was the noble Perpetua herself who controlled the outcome, as she “took the hand of the trembling gladiator and guided it to her [own] throat” (§ 21, Mursurillo 1972:131).

DEVOTEES

The memory of Perpetua, Felicitas, and their companions persisted throughout North Africa [Image at right] in the immediate aftermath, and they continue to be remembered and venerated throughout the Church today. The bodies of the martyrs were buried south of Carthage on a highly visible plateau, a site where an annual festival was celebrated on the anniversary of their deaths. By the early fourth century, that date had been added to the official calendar of the church at Rome (Salisbury 1997:170; Shaw 1993:42). Indeed, by the fourth century, the account of Perpetua’s passion had become immensely popular, to the extent that it was revered by Christians “almost as if it were scripture” (Salisbury 1997:170). The great fourth-century North African bishop, Augustine, is known to have preached at least three festival day sermons based on the Passio; albeit in a manner that downplayed the power and authority of the martyrs, particularly in regard to the women (Shaw 1993:36–41; Salisbury 1997:170–76). In doing so, he and others rendered these earlier heroes of the faith less of a threat to the increasingly hierarchical Church; at the same time, his work reinforced and kept their memory alive. Similarly, in the thirteenth century, Jacobus de Voragine included a re-worked version of Perpetua’s story in his compilation of saints’ lives, the Golden Legend (de Voragine 1993:342–43).

Veneration of Perpetua and her companions, including the annual public reading of her diary, continued at the site of the martyrs’ remains, over which a basilica had been erected. These celebrations continued until the mid-fourth century when the Vandals conquered the territory and took over the basilica; eventually, with the Arab invasion of the seventh century, the relics of the martyrs were lost (Salisbury 1997:170–76).

Yet, the memory of the North African martyrs, particularly Perpetua, has endured. In the nineteenth century, French excavators working in Carthage recovered the stone that had once marked the graves of the martyrs. In addition, [Image at right] The Missionaries of North Africa (commonly known as the White Fathers) built and dedicated a small chapel to Perpetua on the ruins of the old amphitheater (Salisbury 1997:176–78). Today, the Roman Catholic Church celebrates the feast day of Saints Perpetua and Felicitas on March 7; while Eastern Orthodoxy remembers them with a feast day on February 1.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

The account of these Cathaginian martyrs presents literary, historical and cultural challenges for the modern reader. As has been noted, the text itself purports to be a first-person account of Perpetua’s ordeal, that is, her own diary written in prison. That this is so has been accepted by most scholars. For instance, based largely on the quality and the manner in which Perpetua’s visions are recorded, Brent Shaw asserts that “there is no reasonable question of their authenticity” (Shaw 1993:26). He argues further that the editor’s need to bracket Perpetua’s words with his own suggests that very early on there was “resistance to tampering” with her words (Shaw 1993:31). Still, there is not, and cannot be, absolute certainty on this point. In his analysis of the account, J. W. Halporn notes that the belief that the text contains the actual words of Perpetua (and Saturus) is nonetheless an assumption that should be made with care, considering that it often forms the foundation for discussion (Halporn 1991:224).

Historically, as with other early martyrologies, the account of these martyrs raises the question as to whether these North African Christians were Montanists; that is, Christians who followed a movement, later deemed heretical, that was known as the New Prophecy. During the second and third centuries, prophecy, with strong manifestations of the Holy Spirit, was prevalent in Christian communities, both proto-orthodox and those later deemed heretical; yet, it was especially prominent among those who followed the New Prophecy (Frend 1984:254; Trevett 1996:128). For this reason, the visions of both Perpetua and Saturus, as well as the narrator’s introduction which asserts that “we hold in honor and acknowledge not only new prophecies but new visions as well” (§ 1, Mursurillo 1972:107), has led some scholars to view this community as distinctly Montanist (see Klawiter who argues that “Without a doubt the document was authored by a member of the New Prophecy,” Klawiter 1980:257). Others have suggested that at the very least these Christians must have had strong Montanist leanings (see Mursurillo who views the Passio as most likely “a proto-Montanist document,” Mursurillo 1972:xxvi).

Regardless of whether Perpetua and her companions were actually followers of the New Prophecy, it is certain that the text portrays this woman as powerfully endowed with the gift of the Holy Spirit, given her dreams and visions. In her first and fourth visions, Perpetua is able to foresee the future and even to prophesy about it, while in the second and third, the Spirit manifests itself by revealing the power of prayer through which her suffering brother is healed. For the imprisoned Christians, much strength must have been gained as they watched the Spirit revealing itself in Perpetua. It is likely, however, that these same spiritual powers made Perpetua, Felicitas, and the rest of these Christians vulnerable to persecution, since the pagans would have regarded such practices as being aligned with magic and sorcery. Septimius Severus, who was emperor in 203, was known as one who sought to root out magicians, astrologers, and those who claimed to have prophetic dreams: “Even those who merely possessed magic handbooks were threatened with the death sentence” (Wypustek 1997:276). Such practices were deemed exceedingly dangerous since dabbling in them was believed to anger the gods and thus to bring upon the community all manner of trouble, including famine, plagues, and earthquakes. Wypustek suggests that Perpetua’s father, who could not have comprehended his daughter’s fascination with the Christian god, quite likely believed her to have been under a spell placed upon her by a professional hypnotizer, which was a specialization within the magic arts of the time (Wypustek 1997:284). That Perpetua was able to endure extreme acts of torture, that she did not appear to feel pain, and that she maintained an aura of serenity even as she guided the gladiator’s sword to her own throat only served to cement the notion that she had to have been spellbound. In addition, prayer, particularly silent prayer and lengthy prayers, both of which Christians engaged in with great fervor, were often seen by pagans as magic curses, frequently offered up with criminal intent. For pagan officials, the Christian magic, unleashed through prayer on behalf of the pregnant Felicitas must have seemed especially terrifying. Here was a young woman who because of her pregnant state, still had time to recant; yet, once her fellow Christians prayed over her, she gave birth to a child prematurely, just as they had asked. This must have been seen as “uterine magic” at its best (or worst, depending on perspective) since there are known to have been magicians who boasted of their ability to control the pregnant womb; sometimes lengthening and sometimes hastening delivery (Wypustek 1997:283).

While “uterine magic,” at least in the ancient sense, is no longer something with which most Christians must contend, this text presents the modern reader with a number of cultural challenges related to issues of gender, both past and present. The text itself, as well as the way it was preserved and presented to the faithful over the course of centuries, reveals the complexity surrounding the female martyr in the ancient world. In her work on gender and language in early Christian martyrologies, L. Stephanie Cobb explores in detail the manner in which communal concern over appropriate roles for women plays out in “two distinct situations, inter- and intracommunal” (Cobb 2008:93). Tracing the interplay of gender roles throughout this text, she shows how the narrator simultaneously emphasizes the masculine and feminine aspects of the female martyrs; such as in the final death scene wherein Perpetua and Felicitas stand defiantly “in the masculine space of the arena” even as the male editor “casts the narrative gaze on their nude bodies” (Cobb 2008:111). Through such depiction, the narrative reflects the basic problem that female martyrs presented for Christian communities: that is, how to assert Christianity’s power over paganism at the intracommunal level, while simultaneously reining in the power of women within the Christian community itself. This is the challenge faced by Augustine and later Church leaders who honored these women as powerful martyrs of the faith, and at the same time sought to limit their popularity in order to uphold gender roles deemed proper within their communities. Augustine, for instance, repeatedly juxtaposed Perpetua with Eve, thus praising her for trampling the serpent in her vision while simultaneously reminding his audience that these “virtuous women were [merely] anomalies in a world that fell due to the actions of a woman, the ‘sex [that] was more frail’” (Salisbury 1997:175). It is quite possible that for the orthodox Church, the work of controlling the stories of such women was critical to strengthening and maintaining the growing male hierarchy within the Church. It is also very possible that the need to do so was bound up with the desire of orthodox Christian leaders to purge the growing faith of Montanist elements. As already noted, it is not possible to argue with certainty whether or not Perpetua and her community saw themselves as Montanists. However, it has been strongly posited that followers of the New Prophecy bestowed priestly authority within their communities on persons who had faced martyrdom but who eventually were released rather than killed; and that such authority was granted to women as well as to men (Klawiter 1980:261). If so, perhaps the need of orthodox leaders to portray women such as Perpetua and Felicitas as anomalies, rather than as useful role models for this life, becomes clearer.

For both the narrator of this text and later Church leaders, the problem of how to present female martyrs as powerful, and yet also properly feminine, persisted. The story of Perpetua and Felicitas complicated this task further because of their status as mothers. In their resistance to pagan authority, these women rejected not only pagan gods and worldly authority figures such as the Roman governor and Perpetua’s father, but also their own children. While grieved by the loss of her child, Perpetua rejoiced that her milk dried up and that the burden of worry over her son was removed from her. For her part, Felicitas prayed to be relieved of the burden of pregnancy in order that she might die with her comrades, and then upon delivery she immediately gave the child over to another. This giving up of children is not particularly surprising, given that the very term “martyr” implies that one has resisted to the point of death and thus has accepted the necessity of giving up all worldly attachments. What is surprising is that while one might presume that some men in the group also had children, that point is not raised, whereas the women’s parental status is not only noted but highlighted. Perpetua’s father and even the governor repeatedly exhort her to have pity on her baby and to recant (§ 5 and 6, Mursurillo 1972:113–15); and Felicitas is recorded as going to the arena “fresh from childbirth with the milk still dripping from her breasts (§ 20, Mursurillo 1972:129). As historian Gillian Cloke notes, “This constitutes a major divergence in the representation of men and women in the martyr sources . . . this restraint further defines women in terms of their perceived fate as ‘weaker vessels’; it is proper for them to rise above it, but it is still not proper to represent them as being without it” (Cloke 1996:47).

Because of the maternal status of both Perpetua and Felicitas, the uneven representation of male and female martyrs is particularly pronounced in this text. There is no doubt that Perpetua is a woman, a member of the “weaker sex,” and yet, the text also leaves no doubt that she is a woman who rises above her own sex. This is clearest in her fourth vision wherein Perpetua, a woman, says that she became a man, a powerful man, with a male body in which she victoriously trampled on the head of the serpent. It is as if in her own mind, Perpetua could not conceive of winning this fight “with the Devil” as a woman; rather, winning the victory would require a male body. Given the patriarchal context in which Perpetua lived, this is perhaps not very surprising. As she examines various levels of resistance implicit in this text, Lisa Sullivan notes that Perpetua herself does not seem to be surprised or alarmed by it, and suggests that it represents “an example of a member of the submissive group (female) appropriating the imagery of the dominant (a powerful male body) in order to converse on the dominant’s terms” (Sullivan 1997:73).

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGIONS

Today, the account of Perpetua and Felicitas continues to be popular among Christians and has become critically important to the study of women in religions in general. Perpetua’s story is particularly significant, not only because of her faith and powers of endurance but also because of the specific manner in which she died. Unlike other Christian martyrs whose tormentors eventually killed them, Perpetua is said to have guided the sword to her own throat. According to the narrator, “She screamed as she was struck on the bone; then she took the trembling hand of the young gladiator and guided it to her own throat. It was as though so great a woman, feared as she was by the unclean spirit, could not be dispatched unless she herself were willing” (§ 21, Mursurillo 1972:131). Thus, Perpetua’s story represents, within Christian tradition, a clear instance of deliberate self-sacrifice, that is, suicide. While not entirely unique (the early martyr, Agathonice, was said to have thrown herself to the flames, and the fourth century Church historian, Eusebius, reported that one woman and her daughters had voluntarily thrown themselves in the river) Perpetua’s means of death illustrates a noble death played out in a long tradition of self-sacrifice as a means of appeasing the gods (Miller 2005:45; Maier 1999:302). Archaeological excavations in Carthage have revealed the bones of numerous sacrificial victims; children who died by having their throats cut, as well as adults who sacrificed themselves for what they perceived to be the good of their community (Salisbury 1997:49–57). Woven into the fabric of cultural memory in North Africa were powerful models for women, the most prominent of which was Queen Dido, whom in Virgil’s telling, built her own funeral pyre, then climbed upon it and stabbed herself with a sword (Salisbury 1997:53). After being conquered by Rome, the Carthagians banned self-sacrifice; yet vestiges of it remained in the form of gladiatorial combat. Perpetua, educated and steeped as she was in North African tradition, would have understood the significance of guiding the sword to her own throat. The choice was hers; and, according to the narrator, who bestows great honor on her for it, Perpetua made the choice to die by her own hand.

Today, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that suicide is a leading cause of death in the United States, the rate having increased significantly between 1999 and 2016 in nearly every state (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Factors leading to suicide are many and varied. Clearly, choosing to die as an act of religious resistance differs from choosing death for other reasons. Even so, Perpetua’s means of death introduces a certain amount of ambiguity for Christians in that orthodox Christianity has consistently spoken against suicide and yet, in this case, it has honored and continues to lift up as a role model, a woman whose contribution to the tradition includes the important factor that she chose to die by that means.

Certainly, Perpetua, Felicitas, and the companions who died with them operated within their own cultural context. [Image at right] They lived with their own cultural memories; and they understood and made use of the terms and imagery of Roman authority as well as that of their own North African world. In terms of gender, it is highly likely that they (as well as leaders and readers who followed them) understood the female body as “a distinct liability” (Cardman 1988:150). Even so, this text’s very strong sense that women represent the weaker sex, complete with Perpetua’s vision of herself as a man, presents a strong challenge to the modern reader. It has become common in recent years to question whether martyrologies such as the Passio are still useful for our day or whether the ancient cultural overlay and specifically the patriarchal context, laden as it is with oppressive imagery and baggage, renders stories such as that of Perpetua and Felicitas irrelevant, or even damaging, for Christians, especially Christian women. In comparing the account of the martryrdom of Perpetua and Felicitas to that of a group of American female martyrs in El Salvador in 1980, Beverly McFarlane asserts that the former may offer a viable model of courage and integrity but only when used “with caution” (that is, with an understanding of the cultural context and its implications for women), “and supplemented by other models of martyrdom” (McFarlane 2001:266). She suggests that the case of the American women offers the possibility of a shift in focus of the definition of martyrdom, since they witnessed to Christ (that is, they became martyrs), through the way in which they lived and not only through their act of dying. Perhaps a careful reading of Perpetua’s account might do the same; for instance, if emphasis were to be placed on scenes where she assisted others, such as when, on behalf of her fellow prisoners, she confronted the official guard, arguing for better treatment for all; or, when after being thrown by the heifer, she moved to assist Felicitas, and continued to offer words of encouragement to her brother and the other catechumens (§ 16 and 20, Mursurillo 1972:125 and 129).

Apart from the problem of patriarchal trappings, other thinkers have questioned the value of martyr texts in the modern world, asserting that such texts merely glorify suffering and serve to perpetuate terror, particularly among the most vulnerable in society. These thinkers reject the notion that human suffering, either that of Jesus himself or of those who imitate his death, can ever be redemptive. According to Joanne Carlson Brown and Rebecca Parker such “martyrdom theology ignores the fact that the perpetrators of violence against ‘the faithful’ have a choice and, instead, suggests to the faithful that when someone seeks to silence them with threats or violence, they are in a situation of blessedness” (Brown and Parker 1989:21). But God, they argue, does not demand the suffering and death of his son in order for humans to be saved; and thus, since there is no value in the suffering and death of Jesus, they likewise find no value in the suffering and deaths of his followers. In short, suffering, they assert, is not salvific; it is never positive, nor is it necessary for social transformation.

Nonetheless, other thinkers continue to view martyrologies in general, and particularly this account of Perpetua and Felicitas, as indispensable to the tradition; seeing such texts as inspirational and empowering, especially for those most marginalized within society. Lou Ann Trost, for example, agrees with Brown and Parker that suffering itself is not redemptive and can never be redeemed. However, she asserts that “It is a person’s life which is redeemed from suffering, bondage, sin and death” (Trost 1994:40). In this view, atonement, that is, the substitutionary sacrifice of Jesus that occurs in his suffering and death, can never be isolated from his life, his teachings and his resurrection. Instead, “Atonement must be held within the context of the doctrine of incarnation, of belief in the trinitarian God whose creative love is ever healing and restoring the world, who in Jesus frees all from the power of evil, whose ultimate life-giving is in Jesus’ resurrection [not just his death]. . .” (Trost 1994:38). For those who adopt this perspective, the power of the account of Perpetua and Felicitas is not in their deaths but rather in the courage and faith that they displayed while still in this life; and in the vivid presence of the Holy Spirit, “proof of God’s favour,” that is manifest in Perpetua’s visions and in the endurance that she, along with Felicitas and their comrades, displayed throughout the ordeal (§ 1 Mursurillo 1972:107).

Certainly, Christians throughout the centuries have felt the allure of the Passio; as in ancient times, the text continues to garner strong attention today. This is evident not only in the fact that the work has generated numerous scholarly books and articles, but also in that it continues to capture the imagination of the populace who today, along with reading it, are also able to access animated versions, one created specifically for children (“Catholic Heroes of the Faith”). Thus, the Church throughout the ages has held this text in high esteem, understanding as did the anonymous editor, that such stories provide “spiritual strengthening” as well as “comfort to men [sic] by recollection of the past through the written word” (§ 1, Mursurillo 1972:107). [Image at right] For Christians, individually as well as collectively, the voice of Perpetua and the story of her and Felicitas is powerful. Through the process of living and dying as witnesses to Christ, these women are understood to have attained unity with Christ; and in becoming one with Christ, they each found their true identity. In her first encounter with her father after being arrested, Perpetua declared: “I cannot be called anything other than what I am, a Christian” (§ 3, Mursurillo 1972:109). Indeed, her story makes clear that while others saw her (and continue to see her) as an educated Roman matron, a North African, a woman, and a mother, she herself rejected all of those labels, claiming only the label of “Christian.” In understanding her story, it is necessary to acknowledge the culture in which she lived while at the same time attempting to approach her on her own terms, for already at this early stage, she identified not with her earthly family but rather with Christ. And already, Perpetua, Felicitas, and their companions were on a journey of transformation, a journey in which they were being perfected in grace, and on which they moved ever closer toward one-ness with her God.

IMAGES

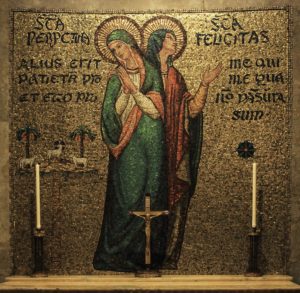

Image #1: Sts. Perpetua and Felicity. By Br. Robert Lentz.

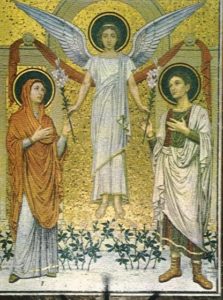

Image #2: St. Perpetua. Archiepiscopal Chapel, Ravenna, Italy. Mosaic. 6th century. Photo by Nick Thompson.

Image #3: St. Felicitas. Archiepiscopal Chapel, Ravenna, Italy. Mosaic. 6th century. Photo by Nick Thompson.

Image #4: Saints Felicity and Perpetua. Perpetua is dressed as a man.

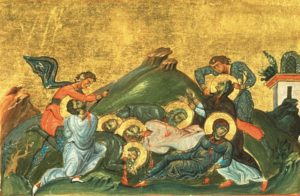

Image #5: Depiction of the martrydom of Perpetua, Felicitas, Revocatus, Saturninus, and Secundulus in Menologium of Basil II, illuminated service book made for for Byzantine Emperor Basil II (r. 967–1025).

Image #6: Perpetua guiding the gladiator’s sword to her neck.

Image #7: Mary and Child with Saints Perpetua and Felicity. Ca. 1520. National Museum of Warsaw.

Image #8: Ruins of the Roman amphitheatre at Carthage, Tunisia. Photo by Neil Rickards, Wikimedia Commons.

Image #9: Mosaic of Sts. Perpetua and Felicity. National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C.

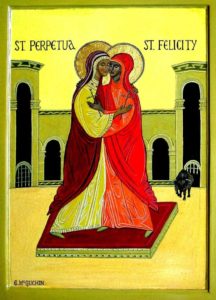

Image #10: Saints Perpetua and Felicity. Eileen McGuckin.

REFERENCES

Barnes, Timothy D. 1968. “Pre-Decian Acta Martyrum.” Journal of Theological Studies 19:509–31.

Brown, Joanne Carlson, and Rebecca Parker. 1989. “For God So Loved the World?” Pp. 1–30 in Christianity, Patriarchy, and Abuse: A Feminist Critique, edited by Joanne Carlson Brown and Carole R. Bohn, New York: Pilgrim Press.

Cardman, Francine. 1988. “Acts of the Women Martyrs.” Anglican Theological Review 70:144–50.

“Catholic Heroes of the Faith: The Story of St. Perpetua.” 2009. Vision Video. ASIN:B002DH20S8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Vital Signs: Suicide rising across the US.” Accessed from https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/suicide/index.html on 20 March 2019.

Cloke, Gillian. 1996. “Mater or Martyr: Christianity and the Alienation of Women within the Family in the Later Roman Empire.” Theology & Sexuality 5:37–57.

Cobb, L. Stephanie. 2008. “Putting Women in Their Place: Masculinizing and Feminizing the Female Martyr.” Pp. 92–123 in Dying to Be Men: Gender and Language in Early Christian Martyr Texts. New York: Columbia University Press.

de Voragine, Jacobus. 1993. “173 Saints Saturninus, Perpetua, Felicity, and Their Companions.” In The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints, trans. William Granger Ryan, 2:342–43. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Eusebius 8.12. 1999. The Church History: A New Translation with Commentary. Trans. Paul L. Maier. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel..

Frend, W. H. C. 1984. The Rise of Christianity. Philadelphia: Fortress Press.

Halporn, J. W. 1991. “Literary History and Generic Expectations in the Passio and Acta Perpetuae.” Vigiliae Christianae 45:223–41.

Klawiter, Frederick C. 1980. “The Role of Martyrdom and Persecution in Developing the Priestly Authority of Women in Early Christianity: A Case Study of Montanism.” Church History 49:251–61.

McFarlane, Beverly. 2001. “Women’s Martyrdom: Death, Gender and Witness in Rome and El Salvador.” The Way 41:257–68.

Miller, Patricia Cox. 2005. Women in Early Christianity: Translations from Greek Texts. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press.

Mursurillo, Herbert, comp. 1972. The Acts of the Christian Martyrs. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Salibury, Joyce E. 1997. Perpetua’s Passion: The Death and Memory of a Young Woman. New York: Routledge.

Shaw, Brent D. 1993. “The Passion of Perpetua.” Past and Present 139:3–45.

Sullivan, Lisa M. 1997. “I Responded, ‘I Will Not. . .’”: Christianity as Catalyst for Resistance in the Passio Perpetuae et Felicitatis.” Semeia 79:63–74.

Trevett, Christine. 1996. Montanism: Gender, Authority and the New Prophecy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Trost, Lou Ann. 1994. “On Suffering, Violence, and Power.” Currents in Theology and Mission 21:1, 35–40.

van Beek, C. J .M. J., ed. 1936. Passio sanctorum Perpetuae et Felicitas. Nijmegen: Dekker and Van De Vegt.

Wypustek, Andrzej. 1997. “Magic, Montanism, Perpetua, and the Severan Persecution.” Vigiliae Christianae 51:276–97.

Publication Date:

30 March 2019