NEIVA CHAVES ZELAYA TIMELINE

1925 (October 30): Neiva Seixas Chaves, known to her followers as Tia Neiva (Aunt Neiva), was born in Própria in the state of Sergipe, Brazil.

1943 (October 31): At age eighteen, Neiva married Raul Alonso Zelaya.

1949: Raul Alonso Zelaya died, leaving Neiva with four young children to support.

1952: After purchasing a truck, Neiva began to work as a driver in various areas in the country’s interior.

1957: Neiva arrived in Brasília, then under construction, to work transporting migrant workers and construction materials in her truck. At the end of 1957, she began to be bothered by visions, premonitions, and other phenomena that she later understood as evidence of her mediumship abilities.

1959: Neiva and a female medium named Maria de Oliveira or Mother Neném (Mãe Neném) established the Spiritist Union White Arrow in honor of Neiva’s chief spirit guide, an Amerindian chief named Father White Arrow (Pai Seta Branca).

1964 (February 9): Neiva and Mother Neném parted ways; Neiva and a small group of her followers relocated to Taguatinga where they established a new community called Social Works of the Spiritualist Christian Order (OSOEC), later known as the Valley of the Dawn (Vale do Amanhecer).

1965: Neiva was hospitalized for tuberculosis from May 11 to August 2. Later in the year, Mário Sassi met Neiva for the first time when he accompanied an acquaintance to OSOEC.

1968: Mário Sassi left his wife, children, and his position at the University of Brasília to join forces with Neiva, becoming her companion, lover, and the intellectual architect of the Valley of the Dawn’s theology.

1969: Neiva relocated OSOEC to a rural area near the city of Planaltina in the federal district outside of Brasília. Followers referred to the area as the Valley of the Dawn.

1971–1980: OSOEC expanded its campus as numerous ritual structures were constructed by community members. The original wooden temple was rebuilt in masonry and stone.

1974 (March): Neiva and Mário Sassi were married in the temple according to OSOEC’s matrimonial ritual.

1978: Neiva created a hierarchy of bureaucratic and ritual authority, headed by the Trinos Triada Presidentes to which she consecrated Mário Sassi and two other veteran men.

1984: Neiva appointed her eldest son Gilberto Zelaya as Coordinator of External Temples and the fourth Trino Triada Presidente.

1985 (November 15): Neiva died. The Trinos Triada Presidentes took over official leadership of OSOEC.

1991: After a series of disagreements and strained relations with the other Trinos, Mário Sassi left OSOEC and established his own community, the Universal Order of the Great Initiates (Ordem Universal dos Grandes Iniciados) in a rural area near the town of Sobradinho.

1994 (December 25): Mário Sassi died.

2009: A dispute between Tia Neiva’s two sons resulted in a split between the OSOEC, led by Neiva’s youngest son Raul Zelaya and headquartered at the Mother Temple, and the CGTA (Coordinação Geral dos Templos do Amanhecer) led by Neiva’s eldest son Gilberto Zelaya and responsible for the external temples.

2000–present: The Valley of the Dawn continued to expand. As of 2018, it included nearly 700 affiliated temples across Brazil as well as the United Kingdom, Italy, Portugal, the United States, and other international locales.

BIOGRAPHY

Neiva [Image at right] was born in 1925 in northeastern Brazil to a traditional Catholic family, the first daughter of four children born to Maria de Lourdes Seixas Chaves and Antônio Medeiros Chaves. Neiva’s early exposure to the Catholic faith had a lasting influence and she never lost her strong faith in God, Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, and other saintly figures of the Church, even as she went on to establish an alternative religious movement known as Valley of the Dawn (Vale do Amanhecer).

Neiva’s father, Antônio Chaves, was an authoritarian figure who expected unquestioning obedience from his wife and children. He believed that a woman’s duty was to take care of house, husband, and children, and, perhaps as a result, Neiva never completed her education beyond the primary school level (although the exact reasons are unclear). Partly to escape her father’s tyranny, Neiva married Raul Alonso Zelaya at age eighteen, and the couple soon started their own family. Six years later Raul died from cirrhosis of the liver, leaving Neiva alone to care for their four young children. Determined to support her family on her own, Neiva initially worked as a  photographer but the close contact with photographic chemicals left her with respiratory problems that would flare up again later in life. After trying her hand at farming, she acquired a truck and learned to drive, becoming one of the first women in Brazil with a professional truck-driving license. [Image at right]

photographer but the close contact with photographic chemicals left her with respiratory problems that would flare up again later in life. After trying her hand at farming, she acquired a truck and learned to drive, becoming one of the first women in Brazil with a professional truck-driving license. [Image at right]

Her father, scandalized by local gossip about Neiva’s contact with male truck drivers, demanded that she return to his household. When Neiva refused, he disowned her and forbade contact with her mother and siblings. Although he eventually reconciled with Neiva near the end of his life, his punitive behavior during her adolescence and young adulthood affected her deeply.

Over the next few years Neiva and her children led a nomadic existence, never settling for long in any one place. In 1957, at the invitation of Bernardo Sayão, an engineer who had employed her late husband before becoming involved in the urbanization of the new federal district, Neiva migrated to Brasília to work as a truck driver. For the first month after their arrival, Neiva, the children, and Gertrudes, an adolescent whom Neiva had taken under her wing, lived in an improvised tent in Núcleo Bandeirante before Neiva secured more permanent housing.

Neiva’s daughter Carmem Lúcia Zelaya recalled in her memoir that not long after arriving in Brasília, her mother began to exhibit severe mood swings and other behavioral changes. The dramatic intensity of these episodes, in which Neiva raged, broke things or swore uncontrollably, troubled her children greatly. Carmem Lúcia reported that she and her brother occasionally had tied Neiva to the bed to prevent her from leaving the house in that altered state (Zelaya 2014:101). Neiva herself later described these episodes as visions and premonitions that alternately disturbed and confused her.

One day Neiva returned home on her lunch break and proceeded directly to her bed, where she lay motionless for hours. Jolted into action by their mother’s state of apparent catatonia, the children sought outside help. A sympathetic neighbor diagnosed Neiva’s condition as obsessão, or the influence of perturbing spirits, and urged her to find a Spiritist center (centro espírita) in order develop her abilities as a medium and thereby restore her spiritual equilibrium. Neiva initially resisted, but at the insistence of her children she attended a series of different Kardecist and Umbanda centers in the area. The family even visited Eclectic City (Cidade Ecléctica), a nearby Spiritist community founded by the self-proclaimed messiah and former air force pilot Master Yokaanam.

In Brazil, Spiritism encompasses a number of religious and therapeutic movements derived from the teachings of Allan Kardec, a nineteenth-century French pedagogue who developed a doctrine about spirit mediumship, reincarnation, and the spirit world (Hess 1991). Kardec’s ideas interacted with other esoteric ideas, as well as religions of African provenience, to produce Umbanda, sometimes heralded as Brazil’s first truly indigenous religion for its pantheon of spirits representing the country’s mix of indigenous, African, and European peoples. In the 1950s, however, practitioners of the varied forms of Spiritism still faced significant social prejudice, and most Spiritist centers were small-scale affairs with little public visibility.

Carmem Lúcia observed that the family’s visits to Spiritist centers had a calming effect on Neiva, whose behavior began to normalize as she learned to recognize and work with what she came to understand as spirit mentors.  Eventually Neiva met a Kardecist medium named Maria de Oliveira, affectionately known as Mother Neném, and the two quickly forged a bond around their similar life experiences. Mother Neném had studied Kardecist doctrines and, according to Valley of the Dawn lore, was instrumental in helping Neiva prepare for her ultimate mission.

Eventually Neiva met a Kardecist medium named Maria de Oliveira, affectionately known as Mother Neném, and the two quickly forged a bond around their similar life experiences. Mother Neném had studied Kardecist doctrines and, according to Valley of the Dawn lore, was instrumental in helping Neiva prepare for her ultimate mission.

In 1959, the two women acquired a piece of land and founded a small Spiritist center called the Spiritist Union Father White Arrow (União Espiritualista Seta Branca). [Image at right] The name honored Neiva’s primary spirit guide, Father White Arrow (Pai Seta Branca), whose last incarnation on Earth was as an indigenous chieftain during the Spanish colonization of the Andes. There, Mother Neném, Neiva, and a small group of family members and followers worked as spirit mediums and took in orphans and children whose parents could no longer  care for them. Before long Neiva attracted a following as a gifted spirit healer among the region’s local inhabitants as well as candangos, manual laborers who had immigrated to the federal district seeking a better future.

care for them. Before long Neiva attracted a following as a gifted spirit healer among the region’s local inhabitants as well as candangos, manual laborers who had immigrated to the federal district seeking a better future.

Most of the spirit entities that Neiva received were figures familiar in the world of Umbanda and other Afro-Brazilian religions as caboclos, or Indians, and elderly black slaves called pretos velhos. In Carmem Lúcia’s memoir, one of the first mentors that Neiva incorporated was the caboclo Chief Tupinambá (Cacique Tupinambá), who later revealed himself to be Father White Arrow. [Image at right] Also important in those early years were the preto velho spirits Father John of Enoch (Pai João de Enoque) and Mother Tildes (Mãe Tildes). Beloved in Umbanda for their wisdom, humility, and grandparently mien, pretos velhos continue to be central figures in the Valley of the Dawn today. Another principal mentor spirit was Mother Yara (Mãe Yara), the companion and alma gêmea (twin soul) of Father White Arrow. In Valley of the Dawn iconography, Mother Yara is depicted as a form of Yemanjá, the Afro-Brazilian goddess of the sea whose own imagery sometimes is syncretized with Our Lady of the Conception. According to Neiva, Mother Yara was a constant, gentle presence instructing her in her mission and reminding her of the need to exemplify in practice the values of love, tolerance, and humility (Zelaya 2014). [Image at right]

need to exemplify in practice the values of love, tolerance, and humility (Zelaya 2014). [Image at right]

Differences between Neiva and Mother Neném, exacerbated by the stress of their difficult living conditions, tested their alliance, and in February 1964 the two mediums parted ways. Neiva, along with a small group of followers, family members, and the forty or so children for whom she was caring, moved to Taguatinga, a small town just outside Brasília (Rodrigues and Muel-Dreyfus 2005:239). There, on June 30, 1964, Neiva registered a new community under the name Social Works of the Spiritualist Christian Order (Obras Sociais da Ordem Espiritualista Cristã) or OSOEC. The members built a wooden temple and, as previously, Neiva and a small group of mediums offered works of spiritual healing to a growing clientele.

In 1965, Neiva was diagnosed with tuberculosis and spent three months hospitalized in Belo Horizonte in the neighboring state of Minas Gerais. Family members and friends attributed her illness partly to the physical stress they believed she had suffered while being initiated into esoteric doctrine under the tutelage of a Buddhist monk named Humarran. Although Humarran resided in a monastery in the mountains of Tibet, according to Valley of the Dawn lore, he and Neiva met daily in the astral dimension where, over the course of five years (1959–1964), he instructed her in advanced esoteric teachings, including a technique of returning to past times and places in order to redeem karma associated with past lives.

That same year, Neiva met Mário Sassi (1921–1994), a spiritual seeker and intellectual dilettante who had moved his family to the federal district to take a position in public relations at the University of Brasília. Sassi arrived at Neiva’s doorstep a skeptic but left, he later wrote, feeling like “I had entered a new world. My life now seemed clear with an explanation for each fact. Suddenly everything started to make sense, to have a logical correctness. I felt invaded by unknown forces and envisioned a welcoming world in which there was a place for me!” (Sassi 1974:15). Sassi began to visit Neiva regularly, commuting to Taguatinga to learn more about her mission and the work of the small community that had gathered around her.

In 1968, after three years of frequent visits, Sassi left his wife, children, and profession to become Neiva’s companion and the intellectual architect of the Valley of the Dawn’s theology. [Image at right] As Sassi later wrote, he was convinced that Neiva was a “superbeing” who “represents the Spirit of Truth [see John 14:16–17 NRSV] and whose fundamental mission is to prepare us for the future.” His own mission would be to “bear witness to the Spirit of the Truth” by synthesizing Neiva’s visionary experiences and forging a comprehensive doctrinal system from the revelations that she claimed to receive from highly evolved entities inhabiting other dimensions (1974:23).

After losing possession of the land in Taguatinga in 1969, Neiva relocated OSOEC for the final time to a rural area near the city of Planaltina. Despite difficulties of access to the new location and the absence  of basic infrastructure (municipal water arrived in 1970 and electricity in 1973), by the early 1970s there were long lines of people waiting to be attended by Neiva, now known as Tia Neiva or Aunt Neiva, and her fellow mediums. Tia Neiva distributed small plots of land to some of her followers, and the town that grew up around the temple, as well as the religion itself, began to be known as Valley of the Dawn. [image at right]

of basic infrastructure (municipal water arrived in 1970 and electricity in 1973), by the early 1970s there were long lines of people waiting to be attended by Neiva, now known as Tia Neiva or Aunt Neiva, and her fellow mediums. Tia Neiva distributed small plots of land to some of her followers, and the town that grew up around the temple, as well as the religion itself, began to be known as Valley of the Dawn. [image at right]

As the decade of the 1970s wore on the community continued to grow. Following the on-going revelations of her spiritual mentors, Tia Neiva, assisted by Mário Sassi and a cohort of veteran members, worked to institutionalize the doctrines, authority structures, and rituals of the religion while also continuing to serve a growing clientele in search of healing for a diverse range of ailments. [Image at right] Long-time members recall this as a period of both incessant work and great trial and error as  they attempted to recreate on the terrestrial plane the things Tia Neiva experienced and learned in her visions, which were described as voyages to different temporal and spatial dimensions or messages received from spirit mentors. Working closely with Tia Neiva, Sassi edited her writings and biographical materials, produced official publications, helped coordinate and lead its corpus of rituals, instructed initiates, and served as the movement’s “secretary general” and official spokesperson. The couple married in the temple in 1974.

they attempted to recreate on the terrestrial plane the things Tia Neiva experienced and learned in her visions, which were described as voyages to different temporal and spatial dimensions or messages received from spirit mentors. Working closely with Tia Neiva, Sassi edited her writings and biographical materials, produced official publications, helped coordinate and lead its corpus of rituals, instructed initiates, and served as the movement’s “secretary general” and official spokesperson. The couple married in the temple in 1974.

Toward the end of the 1970s, conscious of her fragile health and the need to ensure OSOEC’s continuity over time, Tia Neiva began transferring spiritual and bureaucratic authority to a hierarchy of offices open to men only. At the apex were three Triune Triad Presidents (Trinos Triada Presidentes) who jointly held bureaucratic power; beneath them was an advisory council of male heirs. Although equal in stature, Tia Neiva specified that each was responsible for distinct functions: doctrinal, executive, and healing. Mário Sassi, consecrated as Triune Tumuchy (Trino Tumuchy), was responsible for the order’s doctrinal production and its archive.

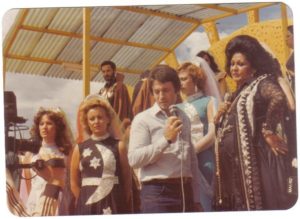

According to Father José Vicente César, a Catholic priest and anthropologist who studied the movement in the mid–1970s, the Valley of the Dawn had approximately 500 resident mediums in 1976 and another 15,000 registered mediums living in the surrounding area who participated in the community’s on-going schedule of spiritual works. Thanks to word of mouth and media coverage, thousands more visited the community for spiritual treatments, including members of the elite whose presence could be discerned by an “appreciable number of luxurious automobiles, high-society ladies, official cars, etc.” (1977:1). César reported that between 50,000 and 70,000 people visited the Valley of  the Dawn monthly, although this number seems exaggerated. Thanks to her charisma and renowned powers of clairvoyance, Tia Neiva was interviewed on television shows and asked for her predictions for the coming year. [Image at right]

the Dawn monthly, although this number seems exaggerated. Thanks to her charisma and renowned powers of clairvoyance, Tia Neiva was interviewed on television shows and asked for her predictions for the coming year. [Image at right]

By 1981, when American anthropologist James Holston first visited, the Valley of the Dawn “had become renowned for its cure and had attracted an enormous following. It had become a famous attraction, a place of spectacular ritual, and as such part of Brasília’s fame as itself a spectacular place” (1999:610). Under the guiding impetus of Tia Neiva’s eldest son Gilberto Zelaya (1944–2017), numerous “external temples” in other Brazilian cities were being established, and over the next decade the Valley of the Dawn’s membership expanded exponentially while the resident population around the Mother Temple grew to about 8,000. In 1984, Tia Neiva consecrated Gilberto Zelaya as the fourth Trino Triada Presidente, responsible for coordinating external temples.

Meanwhile, years of hard work combined with a lifetime of cigarette smoking were taking their toll on Tia Neiva’s weakened lungs and her health was declining rapidly. After a series of respiratory crises that left her dependent on an oxygen tank to breathe, she died on November 15, 1985 at the age of sixty. Her body lay in state in the temple before being buried in the cemetery in Planaltina. Among the 70,000 people who paid their respects were Valley of the Dawn members from across Brazil as well as politicians, including the governor of the federal district José Aparecido de Oliveira. In death as in life, Tia Neiva’s appeal transcended geographic and social divisions.

TEACHINGS/DOCTRINES

The Valley of the Dawn incorporates ideas from many religious and cultural influences present in  modern Brazil and combines them into a unique form that is notable both for its eclecticism and complexity. As indicated by its official name, Social Works of the Spiritualist Christian Order, ideas drawn from Spiritualism (or Spiritism as it is more commonly known in Brazil) anchor the religion’s doctrinal structure. [Image at right] Added to this are concepts such as karma and reincarnation, spirit entities venerated in Afro-Brazilian religions, vocabulary drawn from various esoteric traditions, as well as the belief in extraterrestrial life forms and intergalactic space travel.

modern Brazil and combines them into a unique form that is notable both for its eclecticism and complexity. As indicated by its official name, Social Works of the Spiritualist Christian Order, ideas drawn from Spiritualism (or Spiritism as it is more commonly known in Brazil) anchor the religion’s doctrinal structure. [Image at right] Added to this are concepts such as karma and reincarnation, spirit entities venerated in Afro-Brazilian religions, vocabulary drawn from various esoteric traditions, as well as the belief in extraterrestrial life forms and intergalactic space travel.

Broadly speaking, the Valley of the Dawn merges Theosophical metaphysics with Spiritist practice. It affirms the existence of multiple planes of existence, including the spiritual, astral (or ethereal), and material dimensions, each of which is composed of its own blend of spirit-matter. Communication between these planes, and between spirit entities and humans, is believed to be possible through the practice of mediumship, which is available to all humans. Animated by the divine principle, which Valley of the Dawn members identify as the Christian God, the entire cosmos (including the Earth and humanity) follows a grand scheme of evolutionary and spiritual development that unfolds in sequential cycles. The transition between these cycles is said to be especially fraught and marked by social conflicts, environmental catastrophes, and increased human suffering. According to the doctrine, we are currently in the midst of the transition to the “Third Millennium.”

Driving the evolutionary process are universal laws such as karma and reincarnation. While physicality is a passing state associated with terrestrial existence, the spirit itself is “transcendental,” existing both before and after the physical body and, following the laws of karma, periodically reincarnating on Earth in order to atone for past acts and learn lessons that will facilitate continued evolution. Like many other groups influenced by Spiritist and esoteric literature, popular in Brazil since the writing of Allen Kardec first began to circulate in the late nineteenth century, Valley of the Dawn adherents understand the Earth to be a place of expiation where one can either make amends for one’s karmic debts, evolving into a higher state, or accrue new karmic debts, thus extending the cycle of reincarnation into the future. Reincarnation on Earth is more than just a punishment, but rather a precious opportunity to work toward one’s own spiritual evolution as well as that of the entire planet. Once an individual has evolved to the point that incarnation on Earth is no longer necessary, they continue their journey in the spirit world until finally returning to their origin.

The Valley of the Dawn teaches that some highly evolved spirits of light work on behalf of humanity as mentors while other lower-level spirits can provoke illness and misfortune. The movement understands its principle mission to be the spiritual healing of people and the planet in preparation for the Third Millennium through a vast array of rituals. [Image at right] The most highly evolved spirit of light responsible for overseeing the Valley of the Dawn is Father White Arrow. A statue depicting him adorned with a full-feathered headdress in the style of a Plains Indian chief is, along with a statue of Jesus, a focal point of the Mother Temple.

While Valley of the Dawn members consider themselves Christian, their beliefs and practices depart significantly from those of mainstream Christianity, reflecting the strong influence of Theosophical metaphysics and Spiritist practice. Jesus, for example, is seen as a highly evolved spirit and esoteric master sent by God to restructure both the spiritual and terrestrial worlds by establishing a system of karmic redemption. According to the Valley of the Dawn, Jesus’ teachings of love, humility, and forgiveness offer humans a new path for spiritual evolution referred to as the “Christic System,” or “School of the Way.” By emulating the example of Jesus depicted in the Gospels through the practice of love, tolerance, forgiveness, and charity to others, Valley of the Dawn members believe that they can redeem the negative karma they have accrued over the course of multiple lifetimes.

Members also believe that Jesus brought with him esoteric teachings not addressed in the New Testament, to which they are exposed as they progress through successive levels of initiation. This “initiatic” knowledge is put into practice in a set of rituals that enable participants to “manipulate” or channel specific forces associated with the community’s past incarnations, making these forces available not only for the group’s own benefit but for the benefit of humankind.

The earliest explication of the Valley of the Dawn’s cosmology is found in the writings of Mário Sassi, who saw his mission as synthesizing Tia Neiva’s visionary experiences and forging a comprehensive doctrinal system from the messages that she claimed to transmit from her numerous spirit guides. According to Sassi, the cradle of human civilization is the planet Capella, located in a far-off galaxy. Approximately 32,000 years ago, a group of highly evolved Capelans sent a group of missionaries to establish colonies on Earth for the purpose of preparing it for human civilization. These first missionaries, known as the Equitumans, were not able to complete their mission. Although they made great progress, after several generations they “began to distance themselves from their masters and the original plans” and had to be eliminated from the Earth (Sassi 1974:29).

In order to finish the civilizing process on Earth, the Capelans sent another wave of missionaries, the Tumuchy. Possessors of highly advanced scientific capacities, the Tumuchy possessed great skill in “manipulating planetary energies,” for which purpose they built pyramids and other ancient structures for calculating the relations between various celestial bodies. The Tumuchy were succeeded by the Jaguars, known as “great manipulators of social forces,” who left their mark on various peoples. Concentrated in seven centers around the world, they established the advanced civilizations of the Maya, Egyptians, Inca, Romans, and so forth. Although humans do not recall the Equitumans and Tumuchy today, the memory of them was transformed over time into the various myths of gods who brought civilization to humans.

According to Sassi, as time passed the spiritual descendants of these missionary agents veered away once again from their civilizing mission as their earthly incarnations became seduced by power and warped by cruelty. Finally, God sent Jesus to the Earth where he established the Christic System of karmic redemption, based on the virtues of unconditional love, humility, forgiveness, and the practice of charity or the “Law of Assistance.” Those spirits who adopted the Christic System as a way to redeem their negative karma and return to their original mission became known as Jaguars in homage to one of their incarnations as a group of indigenous Indians living in the mountainous Andes. This group was led by Father White Arrow in his final earthly incarnation. Since then, the Jaguars have been working off their karmic debts in different incarnations across time and space, from colonial Brazil and revolutionary France to the steppes of nineteenth-century Russia. According to Tia Neiva, each Jaguar has passed through at least nineteen different incarnations. The sum total of these various reincarnations constitutes a member’s “transcendental heritage” (herança transcendental).

Father White Arrow, having completed his own evolutionary journey on Earth, commissioned Tia Neiva to continue his mission of helping humans through the difficult transition between cycles. Valley of the Dawn members consider themselves to be present-day Jaguars, reunited by Tia Neiva in accordance with Father White Arrow’s plan. Their presence at the Valley of the Dawn enables them to practice the Law of Assistance through rituals of spiritual healing offered nearly day and night at the temple, but it also offers them opportunities to liquidate their own karmic debts in preparation for the Third Millennium. At that time, Valley of the Dawn members believe, the Earth will enter a new phase and the era of karmic redemption will close. The most evolved spirits, whether incarnate in human form or disincarnate, will be reunited then in their true spiritual birthplace, the distant star known as Capella.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

This complex theology is put into practice in an exceptionally large repertoire of collective rituals, or what the Valley of the Dawn refers to as “spiritual works” (trabalhos espirituais) that occur in spaces  constructed specifically for particular purposes. Each of the approximately fifty rituals performed at the Mother Temple requires numerous participants wearing special vestments and the use of certain hymns, colors, gestures, symbols, and discourses. [Image at right] They occur nearly round the clock, 365 days a year, some multiple times a day, others on a weekly, monthly, or yearly schedule. In order to ensure their smooth performance, the Valley of the Dawn has instituted a complex bureaucracy of offices and roles in which all participants have a part to play.

constructed specifically for particular purposes. Each of the approximately fifty rituals performed at the Mother Temple requires numerous participants wearing special vestments and the use of certain hymns, colors, gestures, symbols, and discourses. [Image at right] They occur nearly round the clock, 365 days a year, some multiple times a day, others on a weekly, monthly, or yearly schedule. In order to ensure their smooth performance, the Valley of the Dawn has instituted a complex bureaucracy of offices and roles in which all participants have a part to play.

While each of these spiritual works is unique in its details, they can be divided into two general kinds. The first are rituals of spiritual healing aimed at alleviating human suffering. Performed as part of the Law of Assistance, these healing works are understood to exemplify the Christic values of unconditional love and compassion and are offered free of charge to all who seek them. The largest variety of healing works is offered on “official work days” (Wednesday, Saturday, and Sunday), and on these days several thousand patients and mediums circulate at the Mother Temple. Temple leaders estimate that up to 12,000 people participate in healing services on a monthly basis.

Like other Spiritist groups, the Valley of the Dawn teaches that many common ailments stem from the prejudicial presence of inferior spirits who lead people toward negative behavior and thoughts. Healing involves the work of “disobsession” (desobsessão), defined as a process of freeing people from the influence of these low-level spirits, thus restoring a person’s spiritual equilibrium. The goal of disobsession is not to exorcize the perturbing spirit, but rather to teach it (and the person) about their true nature and assist them in returning to the path toward God. This pedagogical process is referred to as “indoctrination” (doutrinação).

The second set of rituals, performed for the benefit of initiated members, is intended to redeem the participants’ own negative karma and that generated by key episodes in the Jaguars’ collective transcendental heritage. [Image at right] This set of rituals is understood to “manipulate spiritual energies” in order to liquidate karmic debts accumulated in previous lives.

Valley of the Dawn members learn how to manipulate spiritual energies in a series of “development” (desenvolvimento) courses taught by trained instructors. These are arranged in a hierarchal series of ranks and initiatory levels. As the individual completes these courses, he or she earns the right to wear specific clothing and insignia, participate in certain rituals and take on specific duties in accordance with their position within OSOEC’s complex, multi-leveled bureaucracy. These courses also expose initiates to the details of their shared history as Jaguars and their mission of advancing humanity’s spiritual evolution.

Many of the Valley of the Dawn’s rituals require gently but firmly explaining to unevolved spirits their low spiritual level and helping them along to their appropriate place in the spirit plane, a process known as “indoctrination” (doutrinação) and “elevation” (elevação). This is the job of a category of mediums called “indoctrinators” (doutrinadores). Among Valley of the Dawn members, this is the great innovation of Tia Neiva and what sets the Valley of the Dawn apart from other religions of spirit mediumship. Indoctrinators use reason to help spirits understand the truth of their condition. They can do this because they are capable of a form of mediumship during which they “receive a projection of a spirit entity” while remaining conscious and in total control of their cognitive faculties.

Indoctrinators work in tandem with another type of medium known as apará. These are mediums who incorporate or channel spirit entities so that they can be indoctrinated and elevated by the indoctrinators using a ritual formula or “key” (chave). But aparás do not incorporate low-level spirits exclusively. They also work with “spirits of light” or highly evolved spirit entities committed to helping humans evolve. These “mentor” spirits can take many different forms, manifesting as elderly black slaves (pretos velhos), indigenous Indians (caboclos), healing doctors (médicos de cura), and other spirit entities cultivated in Kardecist Spiritism, Umbanda, and other Afro-Brazilian religions and familiar to most Brazilians.

LEADERSHIP

In order to administer such a large number of rituals involving numerous participants, Tia Neiva [Image at right] developed a complex administrative apparatus involving various hierarchical levels structured as a pyramid. At the upper levels, each occupant of a particular position within the hierarchy is understood to project the spiritual energies of his or her mentor spirit as a “descending force” (força decrescente) that distributes the energy of the spiritual world into the human world.

During her lifetime, Tia Neiva herself occupied the apex of this pyramid, beneath which were the offices of the Trinos Triada Presidentes, originally three, and then four in number. In 2009, the movement was separated into two administrative bodies, each headed by one of Tia Neiva’s two sons, Raul Zelaya (b. 1947) and Gilberto Zelaya. Beneath them are other Trinos with different titles and administrative functions, and beneath these Trinos are the Arcana Adjuncts (Adjuntos Arcanos) who, like the Trinos, are further subdivided into various categories. Although there was one woman among the original thirty-nine Adjuntos Arcanos consecrated by Tia Neiva, today positions at the level of Adjunto and Trino are open only to male indoctrinators due to the belief that their bodies are best able to manipulate the requisite spiritual energies associated with these positions.

As novices complete a sequential series of development courses taught by trained instructors and pass through several levels of initiation, they too ascend through a multi-leveled hierarchy, earning the right to wear specific clothing and insignia, participate in certain rituals, and take on specific duties at each level.

Although the hierarchy is quite complex, one of its most basic divisions is that between men and women. Like many religions, the Valley of the Dawn collapses gender and sex: women, referred to as “nymphs” (ninfas), are believed to naturally possess conventionally feminine traits such as tenderness and emotional sensitivity. [Image at right] Men, known as “masters” (mestres), are said to have greater physical strength and more control over their emotions, which makes them better suited for positions of leadership. Because they possess different bodily capacities and psychosomatic tendencies, men and women together form a complementary dyad and the ideal is for mestres and nymphs to work together, although this is not always realized in practice.

The Valley of the Dawn’s understanding of gender complementarity overlaps in significant ways with its  dual system of mediumship. While in theory anyone can be an indoctrinator or apará, in practice there are more women aparás than men and more indoctrinators who are men than women. As Mário Sassi explained: “because of its emotional tenor, incorporation is more frequent among female mediums. And because the medium who teaches the doctrine tends toward rationalism, one finds the greatest number of indoctrinators among men” (Rodrigues and Muel-Dreyfus 1984:126). The conjunction of strength and the greater degree of rationality and knowledge associated with the indoctrinator means that only male indoctrinators are permitted to command rituals, teach novice mediums as instructors, and assume high-level leadership positions within administrative and ritual hierarchies.

dual system of mediumship. While in theory anyone can be an indoctrinator or apará, in practice there are more women aparás than men and more indoctrinators who are men than women. As Mário Sassi explained: “because of its emotional tenor, incorporation is more frequent among female mediums. And because the medium who teaches the doctrine tends toward rationalism, one finds the greatest number of indoctrinators among men” (Rodrigues and Muel-Dreyfus 1984:126). The conjunction of strength and the greater degree of rationality and knowledge associated with the indoctrinator means that only male indoctrinators are permitted to command rituals, teach novice mediums as instructors, and assume high-level leadership positions within administrative and ritual hierarchies.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

In addition to failing health, some of the most significant challenges that Tia Neiva faced were the on-going financial demands of maintaining the Valley of the Dawn’s spiritual and social works which were, and continue to be, offered freely to the public as an example of Christ-like love. Although the orphanage received some state funds, the community’s other operations were financed entirely through voluntary contributions on the part of group members and from outside donations. To fill the gaps between the community’s financial resources and its needs, Tia Neiva pursued a number of different income-generating endeavors during her lifetime, including a small farm, a flourmill, and a resale shop in Brasília, but none were successful for long. Family and community members recall that her natural generosity and inability to turn away anyone in need meant that profits and merchandise quickly slipped through her fingers. In addition, she also instituted a tradition of communal fundraising activities, such as raffles, bazaars, and charity lunches, that continue today. OSOEC also generates revenue from leasing the properties it owns to various businesses and from a number of small shops that sell religious paraphernalia to adherents.

Thanks to her charisma and healing abilities, Tia Neiva attracted supporters from Brazil’s elite business and political circles and benefitted from their discrete patronage in various ways, from financial contributions to non-monetary forms of assistance. Despite her contact with the prosperous and powerful, however, Tia Neiva always lived in very modest circumstances. As Father José Vicente César observed, “both the Intellectual [Mário Sassi] and the Clairvoyant lead a very poor life, rich in unselfishness, full of sacrifices and even financial anguish because it is not easy to maintain free services of social and spiritual assistance without stable financial resources, depending on occasional official subsidies and the goodwill of the mediums” (1978:63).

Another significant challenge Tia Neiva and her followers faced was the fact that the land on which they had settled in 1969 was federally owned and had been designated for flooding as part of the state’s plans for a hydroelectric plant to ensure the capital’s water supply (Grigori 2017). Anthropologist James Holston reported that when he first visited the Valley of the Dawn in 1981 members lived under the constant threat of imminent eradication (1999:610). Undeterred, Tia Neiva predicted shortly before her death that the eradication order would be rescinded and the land would not be flooded (1999:610). She died before an official decision was reached, however, and in 1986 a local television report on the community’s predicament began with the ominous words: “The Valley of the Dawn, the great mystical city of Brasília, will end” (“Vale do Amanhecer” 1986). Unbeknownst to the public, the governor of the federal district, José Aparecido de Oliveira (1929–2007), had dispatched engineers to study the problem and in 1988 his government adopted a plan that saved the Valley of the Dawn from flooding.

Notwithstanding the existential and financial uncertainties that beset the movement, Tia Neiva’s uncontested charismatic authority ensured that she was able to quickly resolve disputes and preserve group harmony. After her death, however, the balance of power in the leadership ranks shifted and disagreements, exacerbated by differences of personality among the four Trinos Triada Presidentes, flared into the open. Discord first surfaced publicly when Mário Sassi claimed to be working with a group of highly evolved spirits known as the “Great Initiates,” whose arrival had been foretold by Tia Neiva before her death. Sassi’s attempts to interest other Valley of the Dawn members in this work alarmed his fellow Trinos, as well as members of the Zelaya family, who saw it as an unwelcome innovation and a deviation from the standards that Tia Neiva had established. Eventually Sassi left the Valley with a small group of followers to found his own spiritual community with his third wife Lêda Franco de Oliveira, whom he had married in 1986. He died in 1994 after several years of failing health following a stroke in 1991.

While the Valley of the Dawn’s leadership structure remained intact after the tumultuous departure of one of its most central figures, Trino Tumuchy Mário Sassi, an acrimonious dispute between Tia Neiva’s two sons in 2009 resulted in the creation of two separate administrative branches: OSOEC, centered at the Mother Temple outside Brasília and headed by Raul Zelaya, and CGTA (General Council of the Temples of the Dawn) led by Gilberto Zelaya and comprising many of the external temples. Despite this juridical and organizational division, however, there are few differences between the two groups in terms of beliefs and practices. However, the split did strain relationships on both sides, and produced bureaucratic problems and legal wrangling over ownership of the movement’s tangible and intangible resources. In 2010, OSOEC won a preliminary injunction in a civil lawsuit prohibiting the CGTA and all of its members from using any of the liturgies, symbols, and rituals pertaining to the religion, but a federal court overturned this decision in 2011.

Since that time, all of the temples outside of the Mother Temple have aligned themselves with either OSOEC or CGTA, although individual Valley of the Dawn members are free to cross these lines. Despite these and other administrative contretemps, the movement as a whole continues to expand. As of 2018, there were nearly 700 affiliated temples across Brazil as well as Portugal, Italy, the United Kingdom, the United States, and other international locales.

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGIONS

Given the size and international reach of the Valley of the Dawn, Tia Neiva deserves to be better known as an important religious figure of the twentieth century and a charismatic visionary who created a popular religious movement that synthesized multiple influences into a coherent, universalizing message. Historically, she is one of a relatively small number of women who have established successful religious communities that have expanded beyond their local environments to become global movements.

Tia Neiva is one of a long line of women whose charisma and claims of direct superhuman contact enabled them to exercise religious leadership and pursue unconventional lives in social environments that otherwise granted religious, economic, and institutional power to men while restricting women to the domestic sphere. Indeed, her case illustrates several patterns significant to the study of women in religions. The first is the importance of charisma, a form of authority based on an unseen and extraordinary source, in legitimating women’s public religious leadership. Like many female religious leaders in male-dominated environments, Tia Neiva’s visionary and prophetic authority was based on her claim of direct access to supernatural forces coupled with her own dynamic personality. Second, Tia Neiva’s status as a mother was an important element of her self-presentation, a strategy that simultaneously invoked a familiar and culturally acceptable model of female authority while broadening it to the spiritual realm (Sered 1994). She often referred to herself, for example, as her followers’ “Mother in Christ” and addressed nearly everyone as a daughter or son. A third dynamic that recurs among religions founded by women in patriarchal societies is that Tia Neiva partnered with a man, Mário Sassi, who interpreted and systematized her revelations in a series of written publications, facilitating the institutionalization of the movement as well as its public acceptance.

The precedent for women’s sacerdotal and communal leadership that Tia Neiva established, however, was not institutionalized. Before her death, Tia Neiva herself established a bureaucratic structure of authority that reserved the highest positions of communal leadership for men. This too, is a recurring pattern among religions founded by charismatic women. As historian of religions Catherine Wessinger observed, if the larger social environment does not promote women’s equality with men in other ways, the bureaucratization of religious authority inevitably shifts leadership back to men because the “inertia of the patriarchal status quo is too much for one woman to effect significant change singlehandedly” (1996:6, quote on 31).

While many new religions experiment with alternative family structures, sexual practices, or gender roles, Tia Neiva herself did not question conventional sex and gender norms but rather reinterpreted them to sanction women’s spiritual importance. Taken as a whole, Tia Neiva’s revelations expressed a vision of gender complementarity and mutual partnership between men and women that respected women’s sensitive, nurturing, and tender qualities and exalted their femininity while exhorting men to be courteous gentlemen, respectful toward women while also protecting them from harm. Emphasizing the differences between men and women, Tia Neiva taught that each gender possesses its own energetic field. Only by balancing their respective polarities can men and women generate spiritual energy that can be used for healing and transformation. Tia Neiva’s own relationship with Mário Sassi served as an important model for this gendered division of spiritual labor. This makes the Valley of the Dawn attractive to heterosexual people dissatisfied with the exclusion of women’s leadership in the Catholic Church or the many evangelical Protestant churches that have flourished in Brazil over the last few decades.

Despite its emphasis on women’s spiritual power and equal participation with men, in practice the Valley of the Dawn reproduces male dominance in several key ways. Men occupy the highest levels of communal leadership as Trinos and enjoy access to other positions of authority that are not available to women. And while women play critical roles in the collective rituals that are central to the community’s life, only men can “command” or supervise these rituals. As a result, women’s greater sensitivity and spirituality, while highly valorized, also require the protective presence and leadership of men (Hayes 2018). In this, the Valley of the Dawn, like many of the religions founded by charismatic women historically, does not fundamentally question male dominance, but rather reinterprets the traditional qualities assigned to women in ways that foster women’s participation without challenging the patriarchal status quo.

IMAGES

Image #1: Tia Neiva. Courtesy of Arquivo do Vale do Amanhecer.

Image #2: Neiva Chaves Zelaya with truck. Courtesy of Arquivo do Vale do Amanhecer.

Image #3: UESB sign. Courtesy of Arquivo do Vale do Amanhecer.

Image #4: Father White Arrow. Courtesy of Arquivo do Vale do Amanhecer.

Image #5: Mother Yara. Courtesy of Arquivo do Vale do Amanhecer.

Image #6: Mário Sassi and Tia Neiva. Courtesy of Arquivo do Vale do Amanhecer.

Image #7: Vale do Amanhecer entrance. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #8: Tia Neiva in ritual. Courtesy of Arquivo do Vale do Amanhecer.

Image #9: Tia Neiva in television interview. Courtesy of Arquivo do Vale do Amanhecer.

Image #10: Valley of the Dawn adept. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #11: Father White Arrow statue. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #12: Valley of the Dawn ritual. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #13: Opening ritual. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #14: Mário Sassi and Tia Neiva. Courtesy of Arquivo do Vale do Amanhecer.

Image #15: Ninfa. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #16: Mestre. Copyright Márcia Alves.

REFERENCES

Cavalcante, Carmen Luisa Chaves. 2000. Xamanismo no Vale do Amanhecer: O Caso da Tia Neiva. São Paulo: Annablume.

Cavalcante, Carmen Luisa Chaves. 2011. Dialogias no Vale do Amanhecer: Os Signos de um Imaginário Religioso. Fortaleza: Expressão Gráfica Editora.

César, José Vicente. 1978. “O Vale do Amanhecer: Parte III.” Atualização: Revista de Divulgação Teológica Para o Cristão de Hoje 97/98:58–107.

César, José Vicente. 1977. “O Vale do Amanhecer: Parte I.” Atualização: Revista de Divulgação Teológica Para o Cristão de Hoje 95/96:367–91.

Dawson, Andrew. 2008. “New Era Millenarianism in Brazil.” Journal of Contemporary Religion 23:269–83.

Dawson, Andrew. 2007. New Era, New Religions: Religious Transformation in Contemporary Brazil. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Galinkin, Ana Lúcia. 2008. A Cura no Vale do Amanhecer. Brasília: TechnoPolitik.

Grigori, Pedro. 2017. “Criação do reservatório Lago São Bartolomeu estava prevista nos anos 1970.” Correiro Braziliense. November 20. Accessed from https://www.correiobraziliense.com.br/app/noticia/cidades/2017/11/20/interna_cidadesdf,642033/lago-sao-bartolomeu-em-brasilia.shtml on 20 March 2019.

Hayes, Kelly E. 2018. “Where Men are Knights and Women are Princesses: Gender Ideology in Brazil’s Valley of the Dawn.” 197–226 in Irreverence and the Sacred: Critical Studies in the History of Religions, edited by Hugh B. Urban and Greg Johnson. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hayes, Kelly E. 2013. “Intergalactic Space-Time Travelers: Envisioning Globalization in Brazil’s Valley of the Dawn.” Nova Religio 16:63–92.

Hess, David. 1991. Spirits and Scientists: Ideology, Spiritism, and Brazilian Culture. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Holston, James. 1999. “Alternative Modernities: Statecraft and Religious Imagination in the Valley of the Dawn.” American Ethnologist 26:605–31.

Martins, Maria Cristina de Castro. 2004. “O Amanhecer de Uma Nova Era: Um Estudo da Simbiose Espaço Sagrado/Rituais do Vale do Amanhecer.” Pp. 119–43 in Antes do Fim do Mundo: Milenarismos e Messianismos no Brasil e na Argentina, edited by Leonarda Musumeci. Rio de Janeiro: Editora UFRJ.

Oliveira, Daniela de. 2007. “Visualidades em foco: Conexões entre a cultura visual e o Vale do Amanhecer.” Master’s thesis, Federal University of Goiás.

Pierini, Emily. 2016. “Becoming a Spirit Medium: Initiatory Learning and the Self in the Vale do Amanhecer.” Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology 81:290–314.

Pierini, Emily. 2013. “The Journey of the Jaguares: Spirit Mediumship in the Brazilian Vale Do Amanhecer.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Bristol.

Reis, Marcelo Rodrigues. 2008. “Tia Neiva: A Trajetória de Uma Líder Religiosa e Sua Obra, O Vale do Amanhecer (1925–2008).” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Brasília.

Rodrigues, Aracky Martins, and Francine Muel-Dreyfus. 2005. “Reencarnações: Notas de Pesquisa sobre uma Seita Espírita de Brasília.” Pp. 233–62 in Individuo, Grupo e Sociedade: Estudos de Psicologia Social, ed. Aracky Martins Rodrigues. São Paulo: Editora USP.

Sassi, Mário. 1979. Uma Pequena Síntese da História, Atividades e Localização, no Tempo e no Espaço, do Movimento Doutrinário da Ordem Espiritualista Cristã, em Brasília, no Vale do Amanhecer. Brasília, Editora Vale do Amanhecer.

Sassi, Mário. 1977. Instruções Práticas para os Médiuns. Brasília: Editora Vale do Amanhecer.

Sassi, Mário. 1974. 2000: A Conjunção de Dois Planos. Brasília: Editora Vale do Amahecer.

Sassi, Mário. 1972. No Limiar do Terceiro Milênio. Brasília, Editora Vale do Amanhecer.

Sered, Susan Star. 1994. Priestess, Mother, Sacred Sister: Religions Dominated by Women. New York: Oxford University Press.

Siqueira, Deis, Marcelo Reis, et al. 2010. Vale do Amanhecer: Inventário Nacional de Referências Culturais. Brasília: Superintendência do IPHAN no Distrito Federal.

“Vale do Amanhecer – A inundação do solo sagrado – Reportagem.” 1986. YouTube. Accessed from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xXylnk9aXSY (Published August 3 by Ayrton Moussallem Britto).

Vásquez, Manuel A., and José Cláudio Souza Alves. 2013. “The Valley of Dawn in Atlanta, Georgia: Negotiating Gender Identity and Incorporation in the Diaspora.” Pp. 313–38 in The Diaspora of Brazilian Religions, ed. Cristina Rocha and Manuel Vásquez. Leiden: Brill.

Wessinger, Catherine. 1996. “Women’s Religious Leadership in the United States.” Pp. 3–36 in Religious Institutions and Women’s Leadership: New Roles inside the Mainstream, edited by Catherine Wessinger. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press.

Zelaya, Carmem Lúcia Chaves. 2014. Neiva: Sua Vida pelos meus Olhos. Brasília, Coronária.

Publication Date:

24 March 2018