SALLIE ANN GLASSMAN TIMELINE

1954 (December 14): Sallie Ann Glassman was born in South Portland, Maine to atheist parents of Ukrainian Jewish heritage.

1970: Sixteen-year-old Glassman visited the Jane Roberts group in Elmira, New York, and observed Roberts channel the entity known as Seth.

1976: Glassman moved from Kennebunkport, Maine, to New Orleans where she worked as a bartender. Glassman met a psychic reader called André the Martiniquan at the Voodoo Museum on Dumaine Street in the French Quarter. He began to teach her about Vodou.

1980: Glassman and friends formed a group named the Simbi-Sen Jak Ounfo to perform Vodou ceremonies.

1980: Glassman became involved with the creation of a Caliphate Ordo Templi Orientalis group in New Orleans, named the Kali Lodge, and performing weekly OTO rituals.

Ca. 1980–1984: Glassman took painting classes with artist Michael G. Willmon at the Art Institute of New Orleans.

Ca. 1980: At the request of Gerald Schueler, Glassman began making pastel drawings inspired by the Enochian tradition for a deck of Enochian Tarot cards.

Ca. 1988: Glassman went to California to visit Cherel Winett Ito, the executor of the estate of Maya Deren. Glassman was permitted to read the transcripts of Joseph Campbell’s interviews with Maya Deren.

1989: Glassman’s Enochian Tarot deck was published with a book by Gerald and Betty Schueler, The Enochian Tarot.

1990–1992: Vodou rituals were performed in her home from which Glassman drew inspiration for making pastel drawings for a New Orleans Voodoo Tarot card deck.

1992: Glassman’s New Orleans Voodoo Tarot deck was published with a book authored by Louis Martinié, The New Orleans Voodoo Tarot.

Ca. 1993 (June 23): Glassman and members of her Vodou congregation performed the first ceremony at Bayou St. John in New Orleans honoring Marie Laveau, the nineteenth-century Voodoo priestess of New Orleans. This was the beginning of an annual public Vodou ritual performed at Bayou St. John.

1995 (August 18): Glassman performed the first public Vodou ceremony in the Bywater neighborhood in the Upper Ninth Ward of New Orleans to ask Ogou to protect the neighborhood from crime.

1995: Glassman opened Island of Salvation Botanica on Piety Street near her home in Bywater.

1995 (November): Glassman went to Port-au-Prince, Haiti, and was initiated as a manbo asogwe (high priestess) in Vodou by houngan asogwe (high priest) Edgard Jean-Louis and houngan asogwe Silva Joseph.

2000: Glassman published her book titled Vodou Visions.

2005 (June): A peristyle (temple) was completed for the rituals of Glassman’s Vodou congregation renamed La Source Ancienne Ounfo, for which Glassman obtained 501(c)(3) tax exempt status.

2005 (August 29): Hurricane Katrina landed on the Gulf Coast of the United States, causing a storm surge and the breaching of canal levees in New Orleans, resulting in the flooding of most of the New Orleans Metropolitan Area.

2008–2009 (November 1–January 18): Prospect.1 New Orleans, a city-wide international exhibition of contemporary art was held. A building on St. Claude Avenue, which formerly housed a furniture store and which Glassman and her partner Pres Kabacoff were developing into the New Orleans Healing Center, hosted an exhibition of works of art for Prospect.1. A satellite exhibition of works of art included Glassman’s own paintings and the works of other artists.

2008: Glassman and co-workers organized the first Anba Dlo (Beneath the Water) festival held at the Healing Center, highlighting New Orleans culture and music, with a symposium of experts discussing issues relating to water in south Louisiana.

2010 (January 12): A massive earthquake devastated Haiti. Glassman brought Edgard Jean-Louis to New Orleans to stay at her home.

2010 (August 26): Edgard Jean-Louis died at his home in Haiti.

2011: Glassman and Kabacoff moved into the unique home they built in Bywater.

2011 (March): The first New Orleans Sacred Music Festival was held at the New Orleans Healing Center.

2011 (August): The New Orleans Healing Center was officially opened on St. Claude Avenue in New Orleans.

2011 (October): Glassman and Kabacoff married.

2014: Glassman was named 2014 New Orleans Top Female Achiever by the New Orleans Magazine.

BIOGRAPHY

Sallie Ann Glassman (b. 1954) is a manbo asogwe (high priestess) in the Haitian Vodou, or Vodoun, religion, a spiritual counselor, businesswoman, author, educator, social activist, community organizer, and artist, who in the late twentieth century through the early twenty-first century contributed significantly to the reintroduction of Haitian Vodou to New Orleans, Louisiana. Haitian Vodou was first brought to New Orleans in the early nineteenth century with the influx of French-speaking slave owners and slaves from Saint-Domingue (Haiti), fleeing the successful slave revolution there. Haitian Vodou contributed in great part to the unique Voodoo tradition in New Orleans. Prior to the Civil War (1861–1865), slaves, free persons of color, and whites participated in Voodoo rituals in New Orleans. After the Civil War and emancipation of slaves, through the end of the nineteenth century, police regularly broke up Voodoo rituals in New Orleans as part of the effort to maintain whites’ control over African Americans. Expressions of Voodoo continued quietly in the African American community in New Orleans, away from the eyes of whites (Long 2002:90). In the first half of the twentieth century, anything related to Voodoo and Hoodoo (magical practices and products) in New Orleans was seen as fraudulent by the dominant white community (Long 2002:92–94). Beginning in the 1960s through the present, Voodoo came  to be seen in New Orleans as entertainment and a source of tourism dollars; during this period a number of Voodoo and Haitian Vodou practitioners became publicly active in New Orleans (Long 2002:95–97). Sallie Ann Glassman, [Image at right] who was initiated as a manbo asogwe in Haiti, has played a prominent role in bringing Haitian Vodou and its rituals out into the public, and establishing Vodou as an important expression of the unique New Orleans culture. She does this by performing public Vodou rituals, giving interviews, and permitting her ceremonies to be filmed. As is the case with many Vodou practitioners in Haiti and also in New Orleans, Sallie Ann Glassman is an artist. Her artistic work is integral to her worldview and spiritual practice. While Glassman’s spirituality is expressed primarily through her involvement with Vodou and its rituals, she also affirms the mystical aspects, music, dance, myths, and truths of many other religious traditions. She expresses her artistic vision in pastel drawings, gouache and oil paintings, art installations in the form of Vodou altars, shrines, and sacred spaces, and decorating her living, work, and worship spaces to evoke the spiritual reality she senses within and underlying the physical world.

to be seen in New Orleans as entertainment and a source of tourism dollars; during this period a number of Voodoo and Haitian Vodou practitioners became publicly active in New Orleans (Long 2002:95–97). Sallie Ann Glassman, [Image at right] who was initiated as a manbo asogwe in Haiti, has played a prominent role in bringing Haitian Vodou and its rituals out into the public, and establishing Vodou as an important expression of the unique New Orleans culture. She does this by performing public Vodou rituals, giving interviews, and permitting her ceremonies to be filmed. As is the case with many Vodou practitioners in Haiti and also in New Orleans, Sallie Ann Glassman is an artist. Her artistic work is integral to her worldview and spiritual practice. While Glassman’s spirituality is expressed primarily through her involvement with Vodou and its rituals, she also affirms the mystical aspects, music, dance, myths, and truths of many other religious traditions. She expresses her artistic vision in pastel drawings, gouache and oil paintings, art installations in the form of Vodou altars, shrines, and sacred spaces, and decorating her living, work, and worship spaces to evoke the spiritual reality she senses within and underlying the physical world.

Glassman paints Vodou rituals, sacred sites that are human-made as well as natural, and landscapes. She sees everything as being sacred and filled with the spiritual, flowing source of  life. According to Glassman, even things that are “vile,” dark, and decaying are filled with divine life energy. [Image at right] She explains that this is why she is attracted to swamps, such as those in south Louisiana. In swamps, things live, die, decompose, and are recycled in the life and death process. The life, death, and decay process produces fertile soil that gives birth to new life in the forms of bugs, flowers, plants, fish, reptiles, birds, and animals. A swamp is a place for breeding new life while everything in the swamp is being consumed (Wessinger 2017a).

life. According to Glassman, even things that are “vile,” dark, and decaying are filled with divine life energy. [Image at right] She explains that this is why she is attracted to swamps, such as those in south Louisiana. In swamps, things live, die, decompose, and are recycled in the life and death process. The life, death, and decay process produces fertile soil that gives birth to new life in the forms of bugs, flowers, plants, fish, reptiles, birds, and animals. A swamp is a place for breeding new life while everything in the swamp is being consumed (Wessinger 2017a).

Glassman reports that since childhood she has perceived the physical world as not being solid and as merely the surface of a greater force. She sees reality as an “energy flow” with the world as a “reflective image” on top of it. She regards her view of reality as corresponding to the Vodou teaching that there is an “invisible world of spirit within the visible world,” which is “an ocean of life.” She seeks to convey in her paintings the “numinous, energetic presence” within “whatever the surface is.” She terms her painting and drawing style preternatural realism, which is not “supernatural,” but an “extremely heightened natural” (Wessinger 2017a). For Glassman, in addition to learning to know the Vodou lwa (deities) through rituals, possession, making offerings at altars, meeting persons embodying a lwa at that moment, her art is spiritual practice. When creating an altar, drawing, or painting, she is focused and free from thoughts about doing other things. She feels fully present at the “meeting point” between herself and the world and “life itself” (Wessinger 2017b).

Sallie Ann Glassman is the youngest of four children born to atheist parents of Ukrainian Jewish heritage living in South Portland, Maine. Her mother, Jane Glassman, was second-generation Ukrainian American, and her father, James Glassman, was first-generation Ukrainian American. Both sides of Glassman’s family came from the same village in Ukraine. Her father designed shoes, had them manufactured, and traveled to market the shoes wholesale. While her parents were atheists, Glassman had an uncle who was an Orthodox Jew and a Kabbalist, as well as other relatives who were Kabbalists. Her maternal great-grandmother, after whom she was named, was a painter and activist (suffragette) for women’s rights; her great-grandmother was religious and helped establish the first Reform Judaism temple in Wilmington, Delaware. Glassman’s great-aunt on her father’s side was a “seer in the Ukraine.” Family lore said that there was one visionary born into each generation (Wessinger 2017b). When Glassman was a teenager, her mother was critically ill and passed away when Sallie Ann was seventeen.

Glassman’s father, in addition to designing shoes, was a sculptor. Every Saturday he took the children to an art teacher’s house where they were given private art lessons. The children were always encouraged to draw and paint. Glassman’s sister, Nancy Glassman, is also an artist.

At sixteen, Sallie Ann would travel to Elmira, New York, with a teacher, for a course on metaphysics during which she observed author and poet Jane Roberts (1929–1984) channeling an entity called Seth while in trance (Roberts 1970). Seth described human consciousness as having the potential to receive transmissions from higher beings. Seth taught that “Listening to the messages from a supernatural being is thus a matter of switching stations, turning from the ordinary frequency of the mind to a new one. We can, in short, ‘change the channels’ of our awareness, thereby accessing ‘other consciousness selves’” (Urban 2015:324). Sallie Ann’s father was concerned that she might be getting involved with a “cult,” and asked her to write an essay about what she believed. She did and he was satisfied that she was thinking critically. She subsequently decided to move on from the Seth group and teachings (Wessinger 2017b).

Glassman attended Columbia University for one semester. She reports that she made straight A’s, but she decided that the academic way of investigating and thinking was not compatible with her preferred intuitive, creative way of thinking and intelligence (Wessinger 2017b).

In 1976, when Glassman was twenty-two and living in Kennebunkport, Maine, her brother obtained a position at Tulane University. She reports that when he told he was moving to New Orleans, she immediately thought of warm weather (it was then twenty degrees Fahrenheit in Maine), Vodou, and jazz, so she decided to move there also (Wessinger 2017a). She has lived in New Orleans ever since.

Shortly after arriving in New Orleans, Glassman met a man called André the Martiniquan, who was giving psychic readings at the Voodoo Museum on Dumaine Street in the French Quarter. He agreed to teach her about Haitian Vodou, and so she was learning about Vodou before 1980 when she became involved with creating a lodge of the Ordo Templi Orientis in New Orleans (Wessinger 2017a).

involved with creating a lodge of the Ordo Templi Orientis in New Orleans (Wessinger 2017a).

While working as a bartender in New Orleans, in 1980 Glassman and some friends founded a Caliphate branch of the Ordo Templi Orientis (OTO), originally founded by Aleister Crowley (1875–1947). Glassman gave the group the unusual name (for the OTO) of the Kali Lodge, after the Hindu goddess Kālī. [Image at right] Members of the Kali Lodge practiced Enochian magick, which is a complex system of magic that draws in part on the Jewish mystical tradition of Kabbalah, and also on angelic revelations received by John Dee (1527–1608 or 1609) and Edward Kelly (1555–1597) in England, and interpreted by Crowley. Glassman describes Enochian as being the language the angels spoke to Enoch (Wessinger 2017a), a figure mentioned in Genesis 5:19–21, and is described in Hebrews 11:5 in the New Testament as being taken by God, meaning that he did not die but was taken directly into heaven. The Book of Enoch is part of the Jewish tradition but was left out of the Hebrew Bible.

By 1980, concurrent with her activities in the OTO, Glassman was meeting with other persons to perform Vodou rituals worshiping the lwa. The Vodou group that they formed was named the Simbi-Sen Jak Ounfo. As a vegan, Glassman is very concerned about the harm and killing  committed by humans against animals, and so no animals are sacrificed in her Vodou rituals (Paul 2015).

committed by humans against animals, and so no animals are sacrificed in her Vodou rituals (Paul 2015).

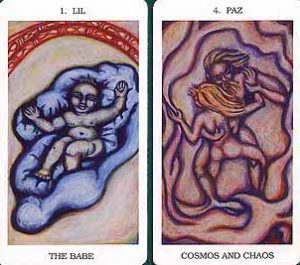

From ca. 1980 to 1984, Glassman took painting classes with artists Michael G. Willmon, Eleanor Smith, and Shirley Rabe Masinter at the Art Institute of New Orleans. During this time, she was asked by author Gerald Schueler to make a set of color drawings for a deck of Enochian Tarot cards. [Image at right] The Enochian Tarot cards along with a book by Gerald and Betty Schueler explaining how to use the Tarot cards as well as practice Enochian magick were published in 1989 (Schueler, Schueler, and Glassman 1989). Glassman’s drawings for the Enochian Tarot cards express her style with figures drawn in pastels with bold, usually black, outlines.

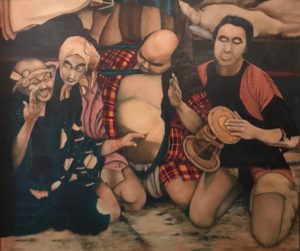

Toward the end of her classes at the Art Institute of New Orleans, Glassman produced her first oil painting. Kurosawa (1984) is a soft, naturalistic, luminous rendering in oil of a black and white still photo from the movie Rashoman (1950) directed by Akira Kurosawa (1910–1998). The movie’s characters are in a court testifying  about their different perspectives on an incident, and Glassman was fascinated by their faces. [Image at right]

about their different perspectives on an incident, and Glassman was fascinated by their faces. [Image at right]

Although Glassman attained the position of Deputy Grand Master in the Caliphate branch of the OTO and felt she had learned a lot and was encouraged by her peers within the order, she was dissatisfied with Aleister Crowley’s views and the actions of some OTO members. She was disturbed by the attitude of some, derived from Crowley, that they were beyond good and evil. She thought that Crowley was misogynistic, bigoted, and disagreeable (Wessinger 2017a). She did not like his condescending attitude toward Haitian Vodou, with which she was increasingly involved. Glassman left the OTO by the late 1980s (Wessinger 2017b).

A friend with a company that distributed experimental films made Glassman aware of the films of Maya Deren (1917–1961), a Jewish woman who was born in Kiev, Ukraine, whose family relocated to Syracuse, New York and obtained United States citizenship. Deren visited Haiti from 1947 to 1954, and participated in Vodou rituals there, which she also filmed. In 1953, Deren’s book, edited by Joseph Campbell, titled Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti, was published. Deren’s film footage of Vodou rituals in Haiti was edited after her death by her husband Teiji Ito (1935–1982), and his subsequent wife and Deren’s good friend, Cherel Winett Ito (1947–1999). The documentary film, also titled Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti, was released in 1985.

Glassman was captivated by Maya Deren’s life and work, and regarded her as her “hero.” In 1988, Glassman traveled to California with her friend who had introduced her to Deren’s work to visit Cherel Winett Ito, who was the executor of Deren’s estate. When they entered Cherel Ito’s living room, Glassman saw a lovely metal statue of Lasirén, the mermaid lwa in Haitian Vodou. An offering bowl containing pink rose petals had been placed before Lasirén. Glassman was immediately attracted to Lasirén. (She subsequently learned that Lasirén was one of the lwa who rule over her head.) Cherel Ito showed Glassman Maya Deren’s asson (beaded rattle that is given at the time of initiation in Vodou), as well as photographs of Deren with her husband Teiji Ito. Glassman was permitted to read unpublished transcripts of audiotaped interviews of Maya Deren by mythologist Joseph Campbell (1904–1987) (Wessinger 2017a). The influence of Maya Deren’s work and being able to visit Cherel Ito and have direct exposure to Deren’s life, as well as to Lasirén, sealed Glassman’s commitment to Vodou and motivated her to create the New Orleans Voodoo Tarot cards (Wessinger 2017a; see also Packard 2009).

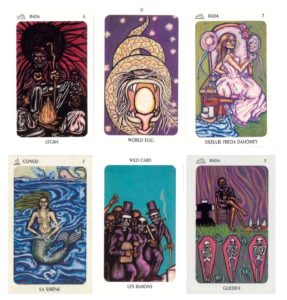

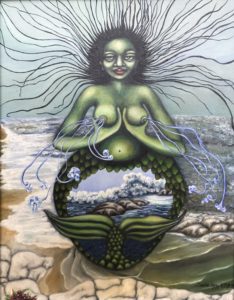

For three years from 1990 to 1992, Glassman, author and percussionist Louis Martinié, his wife, author and artist Mishlen Linden, and Glassman’s husband at the time, sculptor John Herasymiuk, performed Vodou rituals for each of the lwa that Glassman drew using pastels. During the ceremony for a particular lwa, Glassman would receive visions and hear things while in the trance state. Then she would draw. She reports that she had no preconceived notion of what she would draw. She used chalk pastels so she could mark and scratch and put intensity into the  spontaneously drawn image. She states that often she would not know what the image would be until after it was finished. These drawings were subsequently published as the New Orleans Voodoo Tarot, with a book authored by Louis Martinié (Martinié and Glassman 1992). [Image at right] Each card contains a color print of one of Glassman’s drawings on the front, with a veve (see explanation below) for the tarot deck on the back. The drawing on each card is replicated in black and white in the book along with Martinié’s explanatory text. Next to the black and white image of each card is a drawing of the veve for that lwa made by Glassman. Most of the figures on the New Orleans Voodoo Tarot cards are African, in tropical New Orleans settings that could pass for Haiti. Some of the figures represent lwa, others are Vodou serviteurs of the lwa. The faces of all the figures are highly expressive.

spontaneously drawn image. She states that often she would not know what the image would be until after it was finished. These drawings were subsequently published as the New Orleans Voodoo Tarot, with a book authored by Louis Martinié (Martinié and Glassman 1992). [Image at right] Each card contains a color print of one of Glassman’s drawings on the front, with a veve (see explanation below) for the tarot deck on the back. The drawing on each card is replicated in black and white in the book along with Martinié’s explanatory text. Next to the black and white image of each card is a drawing of the veve for that lwa made by Glassman. Most of the figures on the New Orleans Voodoo Tarot cards are African, in tropical New Orleans settings that could pass for Haiti. Some of the figures represent lwa, others are Vodou serviteurs of the lwa. The faces of all the figures are highly expressive.

After the New Orleans Voodoo Tarot cards were published in 1992, more people in New Orleans came to know that Glassman was practicing Vodou. She was tending bar at Café Istanbul, then on Frenchmen Street in the Faubourg Marigny, downriver from the French Quarter, in New Orleans. She learned that many of the people who came to Latin Night at Café Istanbul were santeros (initiated priests in Santería) and babalawos (Ifa diviners in Santería). Santería is the religious tradition from Cuba that resulted from the blending of the Yoruba religion and Catholicism by Yoruba slaves taken to Cuba during the transatlantic slave trade. Glassman found that due to her knowledge of Vodou, which contains elements of the religions of the Yoruba and Fon peoples brought to Haiti as slaves, she and the practitioners of Santería could communicate and understand each other in terms of these African-derived religions. Glassman began learning more about Santería and its deities.

Beginning in 1993, Glassman and her ritual group performed their first St. John’s Eve Vodou ceremony at Bayou St. John in New Orleans on June 23. This ceremony became an annual tradition honoring Marie Laveau (1801–1881), the nineteenth-century Voodoo priestess of New Orleans, who conducted a St. John’s Eve ceremony each year either at Bayou St. John, or on the shore of Lake Pontchartrain north of New Orleans. In Glassman’s annual St. John’s Eve ceremony, a Vodou head-washing ceremony is performed. Headwashings are a form of Vodou baptism, often occurring as the beginning of an initiation. Headwashing ceremonies can also be performed to anoint the head as though it were an altar so the lwa can enter. They can also be performed as a way to cool or calm the head when agitated or “too hot” (Glassman 2018).

On August 18, 1995, Glassman performed her first public crime prevention Vodou ceremony to  the Vodou lwa Ogou (Ogun in the Yoruba religion and Santería) so he would protect residents of the Bywater neighborhood, where she lived, from crime. She opened the Island of Salvation Botanica at 835 Piety Street, [Image at right] so named because she wanted the shop to be an island of salvation for kids growing up in a violent neighborhood.

the Vodou lwa Ogou (Ogun in the Yoruba religion and Santería) so he would protect residents of the Bywater neighborhood, where she lived, from crime. She opened the Island of Salvation Botanica at 835 Piety Street, [Image at right] so named because she wanted the shop to be an island of salvation for kids growing up in a violent neighborhood.

Tina Girouard (b. 1946), a performance and installation artist, and author of The Sequin Artists of Haiti (1994), invited Glassman to go with her to Haiti for the ceremony for Gede in November 1995. Shortly after the invitation from Girouard, Glassman received a call from Dr. Jacques Bartoli, M.D., in Haiti, saying that houngan asogwe (high priest) Edgard Jean-Louis (1921–2010) had consulted with the lwa, and they said that Glassman should come to Haiti and be initiated. Jean-Louis was a Vodou sequin flag artist and well-known houngan asogwe living in the Bel Air neighborhood in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Glassman went to Haiti expecting that she would receive a preliminary initiation, but she was initiated as manbo asogwe (high priestess) in Vodou (Wessinger 2017a). A manbo asogwe may initiate persons into the duties of serving the lwa.

Edgard Jean-Louis was Glassman’s papa in Vodou, and they became close. She went to Haiti six times during the succeeding years, and he visited her home in New Orleans multiple times. During this period, Glassman transcribed Vodou songs and liturgies in Haitian Kreyol. She speaks French when performing Vodou rituals while the songs are sung in Kreyol (Wessinger 2017a). Jean-Louis told Glassman that she could make innovations in the practice of Vodou as long as she stayed within the light of Vodou. He also told her that if she made innovations, it would be controversial among Vodou practitioners outside her own group (Glassman 2017).

During the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival of 1996 there was a new International Pavilion, which that year showcased the arts and culture of Haiti. Edgard Jean-Louis came to New Orleans, and every day of the Jazz Fest, before the festival opened, he and Glassman performed Vodou ceremonies. Glassman reports that stagehands became possessed during the rituals (Wessinger 2017a). The stage manager was Stephen Rehage, who on October 30, 1999, organized the first Voodoo Fest (Voodoo Music Experience, later the Voodoo Music and Arts Experience), which has become an annual tradition in City Park in New Orleans.

Although Glassman had closed the Kali Lodge of the OTO to focus on serving the Vodou lwa with a Vodou congregation, she maintained her love for Kālī. As a practitioner of hatha yoga, she was drawn to Hinduism because of its “intersection between the completely supernatural and the  everyday,” and how the people are present to the Hindu deities in their everyday lives (Wessinger 2017b). In her current home in Bywater, Glassman keeps two altars to Kālī. Over the altar to Kālī located in the front foyer of her home is a painting titled Kali on the Battlefield (1997), [Image at right] consisting of Glassman’s visual interpretation of the story in the Devī Māhātmya of the goddess Durgā fighting a demon who replicated himself from every drop of his blood that hit the ground, thereby producing many more demons the goddess had to slay. Durgā became angry, and from her forehead sprang Kālī, who then destroyed all the demons by swallowing them whole. In Glassman’s Kali on the Battlefield, Durgā is on the left of the painting riding her lion mount, drawing her bow and brandishing her weapons, with her face obscured by the lion’s mane. Kālī, wearing a garland of severed heads (each with a unique face) and an apron of severed arms, is in the center of the painting. She tramples the bodies of the demons she has killed while holding a bowl that catches the drops of blood of a huge demon she has stabbed. Her tongue is extended to swallow a demon whose head is held aloft by another hand. Her devotees in the bottom left corner of the painting bow and prostrate themselves toward her. Glassman interprets Kālī’s protruding tongue as indicating she is in a trance as she fights. Glassman states that for persons caught up in the illusion (māyā) of material reality, Kālī is terrifying, but for the devotee who sees beyond illusion, she is the Divine Mother. Glassman appreciates Kālī’s outrageous nature, her combination of death, destruction, and sex. Kālī is a feminine image of power, and throughout all of the life, death, and conflict, she is Mother. According to Glassman, recognizing Kālī’s qualities in ourselves is empowering (Wessinger 2017b).

everyday,” and how the people are present to the Hindu deities in their everyday lives (Wessinger 2017b). In her current home in Bywater, Glassman keeps two altars to Kālī. Over the altar to Kālī located in the front foyer of her home is a painting titled Kali on the Battlefield (1997), [Image at right] consisting of Glassman’s visual interpretation of the story in the Devī Māhātmya of the goddess Durgā fighting a demon who replicated himself from every drop of his blood that hit the ground, thereby producing many more demons the goddess had to slay. Durgā became angry, and from her forehead sprang Kālī, who then destroyed all the demons by swallowing them whole. In Glassman’s Kali on the Battlefield, Durgā is on the left of the painting riding her lion mount, drawing her bow and brandishing her weapons, with her face obscured by the lion’s mane. Kālī, wearing a garland of severed heads (each with a unique face) and an apron of severed arms, is in the center of the painting. She tramples the bodies of the demons she has killed while holding a bowl that catches the drops of blood of a huge demon she has stabbed. Her tongue is extended to swallow a demon whose head is held aloft by another hand. Her devotees in the bottom left corner of the painting bow and prostrate themselves toward her. Glassman interprets Kālī’s protruding tongue as indicating she is in a trance as she fights. Glassman states that for persons caught up in the illusion (māyā) of material reality, Kālī is terrifying, but for the devotee who sees beyond illusion, she is the Divine Mother. Glassman appreciates Kālī’s outrageous nature, her combination of death, destruction, and sex. Kālī is a feminine image of power, and throughout all of the life, death, and conflict, she is Mother. According to Glassman, recognizing Kālī’s qualities in ourselves is empowering (Wessinger 2017b).

Glassman reports that during the rituals for the New Orleans Voodoo card drawings, while in trance she received more information than could be included in the New Orleans Voodoo Tarot card deck. She subsequently used the remaining information in her book, Vodou Visions: An Encounter with Divine Mystery published in 2000. [Image at right] The veve on the cover of Vodou Visions is a Milocan veve, which includes the veve of numerous lwa.

In every Vodou ritual that Glassman performs, she draws on the floor or ground a veve of the lwa being served using sprinkled corn meal. [Image at right] According to Glassman:

The veve are intricate graphic sigils which double as both the signature of the lwa as well as a kind of mouth for feeding the lwa. The veve draw the practitioner inward and call the lwa out of the invisible waters of Spirit. The magic is in the drawing of the veve and the veve themselves are ephemeral, soon to be dispersed when the ceremony is completed (2018). [Image at right]

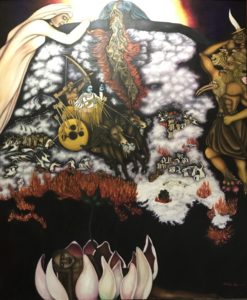

In 2001, Glassman produced a large painting inspired by the Hindu epic, the Mahābhārata. This painting is the second version of a painting that was destroyed in a fire in her house in Bywater. It is inspired by the six-hour television mini-series depicting the stories of the Mahābhārata, directed by Peter Brook, with an international cast, which aired in the United States in 1989. Glassman explained that in watching the series she felt she really knew and cared about the characters, and it is possible to see personalities like them in society. She appreciates that the supernatural aspect and deities are present throughout the  Mahābhārata’s story. Glassman sees Hinduism as being similar to Vodou in that the invisible supernatural reality is part of the visible reality. At the bottom of Glassman’s painting, Mahabharata,[Image at right] a dark sleeping Vishnu is seen dreaming with a lotus arising from his navel. In Glassman’s depiction, the lotus of the created world is afire with the flames of anger and desire that motivated the battle between the Kaurava and Pandava princes to determine which side of the family would rule India. Krishna, the avatar of Vishnu, drives the chariot of Arjuna, the great Pandava archer, through the battle. (Krishna is Arjuna’s teacher in their conversation about life, death, proper action, and spiritual practice in the Bhagavad Gītā, which is set within the Mahābhārata right before the battle begins.) In Glassman’s Mahabharata, the battle is raging with souls flying upward to be devoured by dark universal Shiva. On the right side of the painting there is a demon with upraised knife, who keeps morphing into other terrible beasts. On the left side is the Mother witnessing and grieving the carnage caused by her children, the waste caused by humans killing humans (Wessinger 2017b; Glassman 2018).

Mahābhārata’s story. Glassman sees Hinduism as being similar to Vodou in that the invisible supernatural reality is part of the visible reality. At the bottom of Glassman’s painting, Mahabharata,[Image at right] a dark sleeping Vishnu is seen dreaming with a lotus arising from his navel. In Glassman’s depiction, the lotus of the created world is afire with the flames of anger and desire that motivated the battle between the Kaurava and Pandava princes to determine which side of the family would rule India. Krishna, the avatar of Vishnu, drives the chariot of Arjuna, the great Pandava archer, through the battle. (Krishna is Arjuna’s teacher in their conversation about life, death, proper action, and spiritual practice in the Bhagavad Gītā, which is set within the Mahābhārata right before the battle begins.) In Glassman’s Mahabharata, the battle is raging with souls flying upward to be devoured by dark universal Shiva. On the right side of the painting there is a demon with upraised knife, who keeps morphing into other terrible beasts. On the left side is the Mother witnessing and grieving the carnage caused by her children, the waste caused by humans killing humans (Wessinger 2017b; Glassman 2018).

In 2003, Glassman painted her vision of Lasirén, and she keeps the painting in the small room in her botanica where she gives psychic readings. Glassman relates a number of aspects of her life to her connection with  Lasirén. She was born and grew up next to the ocean. She enjoys being at the beach and swimming in the ocean. She loves working with intuition and being in trance states, doing spiritual work through dreams, and doing mirror magic. She explores the “deep waters of the psyche.” [Image at right] In Vodou the invisible world is understood to be an ocean in which living beings and the visible world float. It is vast, dangerous, and life comes from it. It is Lasirén’s realm (Wessinger 2017b). When Glassman was first told which Vodou spirits rule over her, she was puzzled that they include Lasirén, especially because Lasirén is the patron of song and Glassman is not musical. Subsequently, she related her connection to Lasirén as providing her motivation to spend decades listening to Vodou songs to the lwa in Haitian Kreyol, transcribing them, and teaching them to members of her Vodou congregation (Wessinger 2017b).

Lasirén. She was born and grew up next to the ocean. She enjoys being at the beach and swimming in the ocean. She loves working with intuition and being in trance states, doing spiritual work through dreams, and doing mirror magic. She explores the “deep waters of the psyche.” [Image at right] In Vodou the invisible world is understood to be an ocean in which living beings and the visible world float. It is vast, dangerous, and life comes from it. It is Lasirén’s realm (Wessinger 2017b). When Glassman was first told which Vodou spirits rule over her, she was puzzled that they include Lasirén, especially because Lasirén is the patron of song and Glassman is not musical. Subsequently, she related her connection to Lasirén as providing her motivation to spend decades listening to Vodou songs to the lwa in Haitian Kreyol, transcribing them, and teaching them to members of her Vodou congregation (Wessinger 2017b).

Glassman had a Vodou temple (peristyle) built across Rosalie Alley from her first house in Bywater. When Edgard Jean-Louis performed the ritual to bless the land before the temple was built, the temple’s architect, the City Planner, and members of the New Orleans Historic District Landmarks Commission participated in the ceremony, indicating their support for the revival of Haitian Vodou in New Orleans. The temple was completed in June 2005 (Wessinger 2017b).

Filmmaker Jeremy Campbell filmed the 2005 Hurricane Turning ritual performed in Glassman’s new temple, which is featured in the documentary Hexing a Hurricane (2006). Hurricane Katrina landed on the Gulf of Mexico coast on August 29, 2005, causing the massive flooding of the New Orleans Metropolitan Area and destruction on the coasts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. In the documentary, Glassman points out that Hurricane Katrina in fact turned to the east of New Orleans at landfall, and the disaster would have been much worse in New Orleans if the hurricane had hit the city directly. Every summer, Glassman’s Vodou congregation performs a Hurricane Turning Ceremony [Image at right] to honor the Vodou lwa Ezili Danto (Erzulie Dantor), who, according to Glassman, is identified with Our Lady of Prompt Succor, venerated by local Catholics as the protector of the New Orleans area from all disasters, especially hurricanes. After Katrina, Glassman named her Vodou congregation La Source Ancienne Ounfo, and obtained 501(c)(3) tax exempt status for it from the Internal Revenue Service. Congregational Vodou rituals are typically held on Saturday nights (La Source Ancienne [2018]).

Filmmaker Jeremy Campbell filmed the 2005 Hurricane Turning ritual performed in Glassman’s new temple, which is featured in the documentary Hexing a Hurricane (2006). Hurricane Katrina landed on the Gulf of Mexico coast on August 29, 2005, causing the massive flooding of the New Orleans Metropolitan Area and destruction on the coasts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. In the documentary, Glassman points out that Hurricane Katrina in fact turned to the east of New Orleans at landfall, and the disaster would have been much worse in New Orleans if the hurricane had hit the city directly. Every summer, Glassman’s Vodou congregation performs a Hurricane Turning Ceremony [Image at right] to honor the Vodou lwa Ezili Danto (Erzulie Dantor), who, according to Glassman, is identified with Our Lady of Prompt Succor, venerated by local Catholics as the protector of the New Orleans area from all disasters, especially hurricanes. After Katrina, Glassman named her Vodou congregation La Source Ancienne Ounfo, and obtained 501(c)(3) tax exempt status for it from the Internal Revenue Service. Congregational Vodou rituals are typically held on Saturday nights (La Source Ancienne [2018]).

After the Katrina disaster, Glassman and her partner Pres Kabacoff, a New Orleans developer and CEO of HRI Properties, Inc., met with members of “The Sunday Salon” that Glassman formed to discuss how best to promote recovery, rebuilding, and healing in New Orleans. They wanted to help bring healing on “all levels of sustainability,” physically, emotionally, financially, spiritually, and environmentally. They were advised by a sustainability expert from the United Nations. They decided to focus on a block on St. Claude Avenue, because Ed Blakely, then New Orleans “recovery czar,” in 2007 had designated seventeen “target zones” in New Orleans for investment. The idea was that if development occurred in a target zone, the effect would radiate outwards. One of the target zones selected by Blakely’s plan was the historic St. Roch Market at the intersection of St. Roch Avenue and St. Claude Avenue, which had been badly damaged and flooded by Katrina. Kabacoff and Glassman decided to develop the former Universal Furniture store on St. Claude Avenue, across the street from St. Roch Market, to turn it into the New Orleans Healing Center, which would contain shops and businesses, and rooms for art exhibitions, meetings, lectures, and classes.

Glassman and Kabacoff intend for the Healing Center to benefit and serve people of all races and classes who live in the area. The “Credo” of the New Orleans Healing Center states in part:

We believe our first responsibility is to our local and global community which includes the people and biosphere of New Orleans and the world at large, offering a holistic, safe, clean, sustainable center that provides services, products, and programs promoting physical, nutritional, emotional, intellectual, spiritual, economic, environmental, cultural, and civic well-being.

We agree to work together, synergistically and holistically, and to create a center rooted in hospitality where neighbors are respected and members of the community are welcomed warmly (“Credo” [2018]).

The arts are an important part of the mission of the New Orleans Healing Center. The “Credo” states:

We revere and promote creativity and the arts as powerful agents of transformation. We honor and seek to strengthen the traditions and culture of our community. In meeting the community’s needs, everything we do must be of high quality (“Credo” [2018]).

Glassman promotes artists by displaying their artwork in the Healing Center, even before it was officially opened in 2011. A citywide international art exhibition named Prospect.1 New Orleans displayed works of art in the gutted Universal Furniture building in 2008-2009. Glassman is cognizant of the loss of life in the transatlantic slave trade and slavery in the New World, and that those who survived and their descendants created religious cultures and works of art. She says that Vodou is a “religion of survival” (Glassman 2017). She is aware also of the loss of lives in the Holocaust during World War II. Glassman believes that “each of us is a vessel for this invisible connection to the Divine, and everybody’s precious, and I think art can wake people up to that” (Wessinger 2017b). Glassman feels called to support the creativity of as many artists as she can.

To attract the return of artists to New Orleans after Katrina, Kabacoff and HRI renovated a former garment factory to create in 2008 the Bywater Art Lofts, which low-income artists can rent for reasonable rates. The first Art Lofts were successful, so additional Art Lofts units were constructed.

Hurricane Katrina highlighted for Glassman the significance of water, and the major problems related to it, for south Louisiana and the world. Some areas lack water, while others, such as south Louisiana, have an abundance of water, sometimes too much. Problems of water, climate change, and rising sea levels contribute to erosion of the wetlands in southern Louisiana that have protected New Orleans and other cities from destruction by hurricanes. In 2008, Glassman and co-workers organized the first Anba Dlo (Beneath the Water) festival held at the unfinished Healing Center. It was a celebration of New Orleans art, culture, and music. Anba Dlo as a music and art festival continued to be held annually through 2016 (Wessinger 2017b). In October 2012, in conjunction with the Anba Dlo festival, the first symposium of scientists and environmentalists at the Healing Center discussed the topic of the impacts of water on south Louisiana, New Orleans, and the world. By 2017, the Anba Dlo event consisted of solely the symposium of experts, and the celebratory aspect of the season was shifted to a public festival in the Healing Center and Vodou ritual to commemorate the Day of the Dead/Fèt Gede on November 1 (All Saints Day).

After the devastating earthquake in Haiti on January 12, 2010, Glassman arranged to bring Edgard Jean-Louis to her home. He was very ill with lung cancer. After returning to Haiti for his daughter’s funeral, he died on August 26, 2010 (Wessinger 2017b).

The BP Oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico began on April 20, 2010 with an explosion that killed eleven men on a drilling rig named Deepwater Horizon. The oil from the well poured into the Gulf water and was not stopped until September 10, 2010. The oil spill adversely affected the coasts of Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas, and the wildlife and the livelihoods of people living there. Glassman organized a ritual to apologize to the waters on a beach on the other side of the levee at Oak Street, in the Uptown area of New Orleans, next to the Mississippi River. As Glassman and worshippers were setting up, a huge downpour of rain drenched them. Then the rain stopped, the sun came out, and hundreds of people came over the levee to participate in the ritual and its prayers. It was an interfaith ceremony led by a Vodou priestess. It included Hindu  mantra chanting led by Sean Johnson of Wild Lotus Yoga, and Reiki master Veronica Leandrez sending healing energy to the people and then giving the energy to the water. Other members of the community sang spirituals and led prayers from diverse traditions. Glassman painted Apology to the Waters (2010), [Image at right] from a photograph, to commemorate this ceremony. The dark rain clouds part to reveal the bright sunlight at the top of the painting. The painting is suffused with the orange hues and shadows of near sunset.

mantra chanting led by Sean Johnson of Wild Lotus Yoga, and Reiki master Veronica Leandrez sending healing energy to the people and then giving the energy to the water. Other members of the community sang spirituals and led prayers from diverse traditions. Glassman painted Apology to the Waters (2010), [Image at right] from a photograph, to commemorate this ceremony. The dark rain clouds part to reveal the bright sunlight at the top of the painting. The painting is suffused with the orange hues and shadows of near sunset.

There were numerous big events for Sallie Ann Glassman in 2011. She and Pres Kabacoff moved into a unique home that they designed and built in Bywater and which Glassman decorated (MacCash 2011). In March 2011, the first New Orleans Sacred Music Festival was held in the Healing Center, which has been held annually ever since. The Sacred Music Festival features musicians and dancers, as well as artists, devotees, and altars in religious traditions of the world. Typical events include a Hindu fire sacrifice performed by a Hare Krishna devotee, dancing and chanting by a Tibetan monk, African drumming and singing, dancing by a troupe of young African American girls, spiritually-focused rap, spoken word poetry combined with medieval Christian chants, Native Americans chanting and dancing, Mardi Gras Indians singing and dancing, Japanese Taiko drumming, and Gospel Music performances. In August 2011, the New Orleans  Healing Center (see New Orleans Healing Center [2018]) [Image at right]was officially opened containing the Island of Salvation Botanica (see Island of Salvation [2018]), other shops, a restaurant, a yoga studio, complementary and alternative healing modalities, adult education courses offered by The Street University, a cooperative art gallery, and a health food co-op. In October 2011 Glassman and Kabacoff married.

Healing Center (see New Orleans Healing Center [2018]) [Image at right]was officially opened containing the Island of Salvation Botanica (see Island of Salvation [2018]), other shops, a restaurant, a yoga studio, complementary and alternative healing modalities, adult education courses offered by The Street University, a cooperative art gallery, and a health food co-op. In October 2011 Glassman and Kabacoff married.

In 2014, Glassman was named a New Orleans Top Female Achiever by the New Orleans Magazine for her spiritual and healing work in New Orleans, including the operation of the  Healing Center. Glassman said, “We had three goals with the center. The first was to revitalize the local economy. The second was to create healing at every level—economic, environmental and personal. We also wanted it to serve to unify a polarized community” (Singletary 2014).

Healing Center. Glassman said, “We had three goals with the center. The first was to revitalize the local economy. The second was to create healing at every level—economic, environmental and personal. We also wanted it to serve to unify a polarized community” (Singletary 2014).

On March 14, 2015, in a Vodou ceremony at the Healing Center at the conclusion of the annual Sacred Music Festival, Glassman and members of La Source Ancienne Ounfo dedicated a papier-mâché sculpture of Marie Laveau created by Ricardo Pustiano. The sculpture of Marie Laveau is placed in a shrine [Image at right] just outside the door of the Island of Salvation Botanica inside the large central area of the Healing Center. This shrine is named the International Shrine of Marie Laveau, putting Laveau on same level of Catholic saints, at least in the New Orleans Vodou community. In Glassman’s Vodou community, Marie Laveau is a lwa. Vodou practitioners and others stop by the shrine to pray and make small  offerings.

offerings.

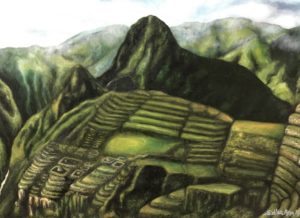

Glassman’s paintings express her fascination with sacred spaces. Glassman and Kabacoff have been to Machu Picchu in Peru twice. She feels immense clarity and positive energy there, and believes that Machu Picchu was built by people in touch with the spiritual energies of their surroundings (Wessinger 2017b). Her painting Machu Picchu (2015) [Image at right] combines Glassman’s interest in sacred spaces with her appreciation of natural landscape and the invisible realities that it reveals.

Mysterious creatures frequently emerge from and inhabit the landscapes in Glassman’s paintings. Glassman’s painting Bizango Night (2002), which hangs in her Vodou temple, is named after the secret society in Haiti that executes judgment. Its members are believed to be shape-shifters with magical powers. They are said to travel through space and time in balls of light. The  Bizango society is associated with turning people into zombies (Wessinger 2017b). Bizango Night depicts these shape-shifters gathering for night-time activities in the swamp next to a grave. [Image at right] The cross on the grave signifies the crossroad between the spirit and material worlds and serves as the threshold to where the Gede spirits live. Glassman explains that:

Bizango society is associated with turning people into zombies (Wessinger 2017b). Bizango Night depicts these shape-shifters gathering for night-time activities in the swamp next to a grave. [Image at right] The cross on the grave signifies the crossroad between the spirit and material worlds and serves as the threshold to where the Gede spirits live. Glassman explains that:

Gede is a special category of being, distinct from the lwa. The Gede rule over death and sex and regeneration, and are the leaders of the family of the Dead. They stand at the crossroads between life and death and are healers, called upon in life and death situations. They are also the patrons of small children. They can be embarrassing and tricky, but are also capable of giving serious answers when asked with sincerity (2018).

When Glassman gave a lecture at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, English professor Maurice W. DuQuesnay told her the Louisiana folktale of the witch of Maurepas Swamp. The story of the Swamp Witch of Maurepas is about a young Irish immigrant, Kate Mulvaney, who settled in New Orleans with her father. Kate fell in love with a man who had a wife in Atlanta. Nevertheless, Kate moved in with her lover, and she was disowned by her father. When her lover inherited a diamond mine, he abandoned her. Kate’s misfortune increased when she was disfigured by smallpox scars. A Voodoo “witch” in New Orleans advised her to go live with a mulatto woman in the Maurepas Swamp. The Voodoo “witch” gave Kate recipes for herbal teas and medicines, and  once in Maurepas Swamp, she traded these medicinal items for fish and small game from local fishers and trappers. One day Kate found an albino fawn next to its dead mother’s body. She named the fawn White Wings, because it had six tufts on its head that made her think of wing buds. After the grown White Wings was shot by a hunter, he appeared to Kate with six wings and took her up to heaven. On the way, she knew her sins had been forgiven (Dubus [2017]).

once in Maurepas Swamp, she traded these medicinal items for fish and small game from local fishers and trappers. One day Kate found an albino fawn next to its dead mother’s body. She named the fawn White Wings, because it had six tufts on its head that made her think of wing buds. After the grown White Wings was shot by a hunter, he appeared to Kate with six wings and took her up to heaven. On the way, she knew her sins had been forgiven (Dubus [2017]).

In July 2017, two of Glassman’s paintings, The Witch of Maurepas Swamp I (2013) [Image at right] and The Witch of Maurepas Swamp II, were displayed in an art exhibition dedicated to “The Swamp Witch” (Swamp Witch Art Exhibition [2017]) at Basin Arts Galleries in Lafayette (Kiburz 2017). In Glassman’s telling of the story, the Swamp Witch lived in the Maurepas Swamp as a recluse, where she ministered to the animals and was beloved by them. She grew old and had the appearance of a hag, but internally she was a beautiful young woman. The white stag she had cared for had six buds on its back, which eventually grew into wings. According to Glassman, “When she and the stag died, they morphed together. And of course, people still see her in the swamp” (Wessinger 2017b).

At the conclusion of the Day of the Dead/Fét Gede in the Healing Center on November 1, 2017,  Glassman and members of La Source Ancienne Ounfo performed a Vodou ritual that dedicated a new fountain sculpture of the Swamp Witch of Maurepas by Ricardo Pustiano. The Swamp Witch, [Image at right] growing up out of the water like a cypress tree rooted in the muck of the swamp, surrounded by vegetation, enveloped in vines and Spanish moss, and accompanied by a skull-topped staff, watches over the activities and rituals in the Healing Center’s foyer.

Glassman and members of La Source Ancienne Ounfo performed a Vodou ritual that dedicated a new fountain sculpture of the Swamp Witch of Maurepas by Ricardo Pustiano. The Swamp Witch, [Image at right] growing up out of the water like a cypress tree rooted in the muck of the swamp, surrounded by vegetation, enveloped in vines and Spanish moss, and accompanied by a skull-topped staff, watches over the activities and rituals in the Healing Center’s foyer.

When asked if the beings revealed in her preternatural realistic artwork actually exist, Glassman replies that she prefers not to answer that question in a concrete manner. They are what she sees, how she sees, what she feels (Wessinger 2017b).

With the New Orleans Healing Center and Island of Salvation Botanica as her base, and her artistic creations and La Source Ancienne Ounfo and Vodou rituals as her spiritual practice and inspiration, Glassman continues her activism on behalf of environmental, artistic, and progressive causes. Her artistic creativity and vision is an indispensable expression of her spiritual life, which appreciates all religious traditions while being grounded in Haitian Vodou. Her artistic and spiritual work are community-based and result in practical efforts to heal people and the environment, especially in New Orleans. Glassman’s drawings and paintings; her Vodou altars, veve, and rituals; the sculptures and works of art by other artists displayed in the New Orleans Healing Center; and her social activism are expressions of her intent to make the underlying spiritual reality manifest to benefit living beings in the physical world.

IMAGES

**All images are clickable links to enlarged representations.

Image #1: St. John’s Eve portrait of Sallie Ann Glassman with altar to Marie Laveau. Bayou St. John, New Orleans, Louisiana. 23 June 2017. Sculpture of Marie Laveau by Ricardo Pustiano. Papier-mâché. Courtesy of Catherine Wessinger.

Image #2: Sallie Ann Glassman, Swamp Light. 2000. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Sallie Ann Glassman.

Image #3: Sallie Ann Glassman at one of the altars to the Hindu goddess Kālī in her home in Bywater, New Orleans, Louisiana. 4 June 2017. Courtesy of Catherine Wessinger.

Image #4: Sallie Ann Glassman, selection of Enochian Tarot cards. 1989.

Image #5: Sallie Ann Glassman, Kurosawa. 1984. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Sallie Ann Glassman.

Image #6: Sallie Ann Glassman, selection of New Orleans Voodoo Tarot Cards. 1992. Pastels on paper. Lwa depicted on cards on the top row, left to right, are: Legba, the gatekeeper and guardian at the crossroads; Damballah, the serpent creator lwa holding the World Egg (the world in potential); Erzulie Freda Dahomey (Ezili Freda Dahomey), lwa of female love and beauty. On the bottom row, left to right, are: Lasirén the mesmerising mermaid, an aspect of Ezili Freda Dahomey; Les Barons, the heads of the Gede family of lwa who rule over death, sex, regeneration, and who stand at the bottom of the crossroads between life and death, below Legba; and Gede (Guedeh). Courtesy of Sallie Ann Glassman.

Image #7: Island of Salvation Botanica when it was on Piety Street in the Bywater neighborhood of New Orleans. 2005. The Vodou spirits depicted in Sallie Ann Glassman’s paintings, top row, left to right: Yemaya, Ogou Sen Jak, Ezili Danto, Bawon Samedi; bottom row, left to right: St. Expedite, Lasirén, Ezili Freda Dahomey at tea with Ogou. Photo by Infrogmation of New Orleans. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Image #8: Sallie Ann Glassman, Kali on the Battlefield. 1997. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Sallie Ann Glassman.

Image #9: Sallie Ann Glassman drawing veve, using corn meal, before the Marie Laveau altar on the Bayou St. John bridge, New Orleans, 23 June 2017. Courtesy of Catherine Wessinger.

Image #10: Sallie Ann Glassman, Mahabharata, 2001. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Sallie Ann Glassman.

Image #11: Sallie Ann Glassman, Lasirén. 2003. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Sallie Ann Glassman.

Image #12: Hurricane Turning Ceremony at La Source Ancienne Ounfo on 15 July 2017. Courtesy of Catherine Wessinger.

Image #13: Sallie Ann Glassman, Apology to the Waters. 2010. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Sallie Ann Glassman.

Image #14: New Orleans Healing Center. Accessed from https://www.neworleanshealingcenter.org/2017-a-year-in-review/ on 25 June 2018. Courtesy of the New Orleans Healing Center.

Image #15: International Shrine of Marie Laveau in the New Orleans Healing Center. 2017. Sculpture by Ricardo Pustiano. Papier-mâché. Courtesy of Catherine Wessinger.

Image #16: Sallie Ann Glassman, Machu Picchu. 2015. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Sallie Ann Glassman.

Image #17: Sallie Ann Glassman, Bizango Night. 2002. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Sallie Ann Glassman.

Image #18: Sallie Ann Glassman, The Witch of Maurepas Swamp. 2013. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Sallie Ann Glassman.

Image #19: Ricardo Pustiano, Swamp Witch of Maurepas. 2017. Papier-mâché, Spanish moss, tree branches, and found objects. Courtesy of Catherine Wessinger.

REFERENCES

Anba Dlo Festival. 2017. Accessed from http://www.anbadlofestival.org/ on 8 August 2018.

Campbell, Jeremy, dir. 2006. Hexing a Hurricane. National Film Network. DVD.

“Credo.” 2018. New Orleans Healing Center. Accessed from https://www.neworleanshealingcenter.org/credo/ on 12 August 2018.

DuBus, Elizabeth Nell. 2017. “Synopsis.” Jonathon Silver Ahhee Photography and Design. Accessed from http://www.silverlightconcepts.com/the-swamp-witch-a-louisiana-folk-tale/ on 11 June 2018.

Girouard, Tina. 1994. Sequin Artists of Haiti. Port-au-Prince: Haiti Arts.

Glassman, Sallie Ann. 2018. Personal communication with Catherine Wessinger. June 14.

Glassman, Sallie Ann. 2017. “La Source Ancienne Ounfò—A New Orleans-Based Vodou Society.” Presentation on a panel titled “Expressions of Vodou/Voodoo in New Orleans.” Kosanba 2017: Twentieth Anniversary Colloquium, November 3.

Glassman, Sallie Ann. 2000. Vodou Visions: An Encounter with Divine Mystery. New York: Villard.

Island of Salvation. 2018. Accessed from http://islandofsalvationbotanica.com/ on 17 June 2018.

Kiburz, Nick. 2017. “Big Name Campus, Community Figures Take Viewers to the Wetlands’ Mysterious Corners in ‘The Swamp Witch.’” Allons! Arts, Entertainment and Everything Acadiana, July 12. Accessed from https://www.thevermilion.com/allons/big-name-campus-community-figures-take-viewers-to-the-wetlands/article_ce302027-835a-5396-8ef7-093436f301dd.html on 20 June 2018.

“La Source Ancienne.” 2018. Island of Salvation. Accessed from islandofsalvationbotanica.com/source-ancienne/ on 17 June 2018.

Long, Carolyn Morrow. 2002. “Perceptions of New Orleans Voodoo: Sin, Fraud, Entertainment, and Religion.” Nova Religio 6:86–101.

Martinié, Louis, and Sallie Ann Glassman. 1992. The New Orleans Voodoo Tarot. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions.

MacCash, Doug. 2015. “New Shrine of Voodoo Queen Marie Laveau Dedicated Saturday (March 14).” New Orleans Times-Picayune, March 9. Accessed from http://www.nola.com/arts/index.ssf/2015/03/sallie_ann_glassman_marie_lave.html on 20 June 2018.

MacCash, Doug. 2011. “Pres Kabacoff and Sallie Ann Glassman Create an Exotic Home in Bywater.” New Orleans Times-Picayune, January 15. Accessed from http://www.nola.com/homegarden/index.ssf/2011/01/pres_kabacoff_and_sallie_ann_g.html on 20 June 2018.

MacCash, Doug. 2010. “Haitian Voodoo Priest Finds Refuge in New Orleans.” New Orleans Times-Picayune, May 16. Accessed from http://www.nola.com/arts/index.ssf/2010/05/haitian_voodoo_priest_finds_re.html on 20 June 2018.

New Orleans Healing Center website. 2018. Accessed from https://www.neworleanshealingcenter.org/ on 17 June 2018.

New Orleans Sacred Music Festival website. 2017. Accessed from http://www.neworleanssacredmusicfestival.org/ on 8 August 2018.

Packard, Morgan. 2009. “The Gumbo of Vodou.” New Orleans Magazine. June. Accessed from http://www.myneworleans.com/New-Orleans-Magazine/June-2009/The-Gumbo-of-Vodou/ on 20 June 2018.

Paul, Andrew. 2015. “The Vegan Vodou High Priestess of New Orleans Isn’t Interested in Animal Sacrifice.” Munchies. April 30. Accessed from https://munchies.vice.com/en_us/article/gvmnwb/the-vegan-vodou-high-priestess-of-new-orleans-isnt-interested-in-animal-sacrifice on 20 June 2018.

Roberts, Jane. 1970. The Seth Material. Cutchogue, NY: Buccaneer Books.

Schueler, Gerald, Betty Schueler, and Sallie Ann Glassman (illustrator). 1989. The Enochian Tarot: A New System of Divination for a New Age. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications.

Singletary, Kimberly. 2014. “Sallie Ann Glassman, 2014 New Orleans Top Female Achievers.” New Orleans Magazine, July. Accessed from http://www.myneworleans.com/New-Orleans-Magazine/July-2014/Sallie-Ann-Glassman-2014-New-Orleans-Top-Female-Achievers/ on 20 June 2018.

The Swamp Witch Fine Art Exhibition. 2017. Jonathon Silver Ahhee Photography and Design. Accessed from http://www.silverlightconcepts.com/the-swamp-witch-a-louisiana-folk-tale/ on 11 June 2018.

Urban, Hugh. 2015. “The Medium Is the Message in the Spacious Present: Channeling, Television, and the New Age.” Pp. 319–39 in Handbook of Spiritualism and Channeling, edited by Cathy Gutierrez. Leiden: Brill.

Wessinger, Catherine. 2017a. Interview with Sallie Ann Glassman, June 4. New Orleans, Louisiana.

Wessinger, Catherine. 2017b. Interview with Sallie Ann Glassman. July 31. New Orleans, Louisiana.

Post Date:

30 June 2018