LE CERCLE HARMONIQUE TIMELINE

1831 (February 20): Henry Louis Rey was born.

1843: Andrew Jackson Davis, the Poughkeepsie Seer, gained spiritual prominence as a subject of mesmeric trances.

1845 (April 9): Joseph Barthet, a French émigré, founded La Société du Magnétisme de la Nouvelle-Orléans.

1847: A. J. Davis began publication of a weekly newspaper in New York City, which promoted his Harmonial Spiritualism, based on philosophy of the Swedish mystic, Swedenborg.

1848 (March 31): The Fox sisters reported mysterious raps in Hydesville, New York. L’institution Catholique pour l’instruction des orphelins dans l’indigence (Catholic Institute or Couvent School) opened.

1850s: Le Propagateur Catholique attacked Mesmerism and Spiritualism.

1852 (May 29): Barthélemy Rey died.

1852 (December): The earliest documented report of northern mediumship in New Orleans; Reverend Thomas Lake Harris of New York City conducted private séances. Joseph Barthet began his francophone séance circle.

1857 (January): Le Spiritualist de la Nouvelle-Orléans of Joseph Barthet began publication.

1857 (April 11): The Banner of Light began publication in Boston, Massachusetts.

1857 (September 3): Henry Rey married Adèle Crocker in St. Augustine Church.

1858: The rivalry between Abbé Perché and Joseph Barthet heated up over Spiritualism.

1859 (December): Emma Hardinge, northern medium and author of Modern American Spiritualism, arrived in New Orleans and gave lectures.

1860 (April 25): The last entry was recorded at Joanni Questy’s house in Rey’s first séance register before the Civil War began.

1860 (December): James V. Mansfield, the Spiritual Postmaster, visited New Orleans.

1861 (January 26): Louisiana seceded from the Union.

1861 (May 2): The Confederate Native Guards was formed.

1862 (May 1): Union General Butler occupied New Orleans. Henry Rey, Edgar Davis, Eugène Rapp, and Octave Rey surrendered weapons to Butler.

1862 (September 27): The first issue of L’Union, and the First Regiment of the Union Native Guards was mustered in.

1863 (April 6): Rey resigned from the Union Army.

1864 (May 10): The séance register was resumed.

1865 (July 5): Rey began his second séance registe. Séances resumed at Valmour’s house.

1865 (November): Séance entries were recorded in the register after several months of absence.

1866 (July 30): The Mechanics’ Institute Massacre occurred.

1867 (March 2): Rey began his Cercle Harmonique.

1868 (April): A liberal Louisiana Constitution was enacted. Rey was elected member of the Louisiana House of Representatives; Henry Clay Warmoth, governor; Oscar J. Dunn, lieutenant governor; and Antoine Dubuclet, state treasurer.

1869 (February 6): Valmour died.

1870 (July 6): The second séance register ended. Séances at Joseph Lavigne’s cigar shop on the corner of Esplanade Avenue and St. Claude Avenue (now Henriette Delille Street).

1871 (December): Reverend James Peebles, the “Spiritual Pilgrim,” visited New Orleans.

1872 (March 5): Rey’s appointment as Tax Assessor expired.

1874 (September 14): The Battle of Liberty Place took place.

1875: Rey’s Cercle Harmonique ended. Rey continued his séance registers alone.

1877: Gustave Pitard employed Rey as first clerk.

1877 (March 4): Hays became President, and Reconstruction ended.

1877 (November 24): The séance registers stopped.

1890 (April): The reunion séance with Soeur Louise and Valmour took place.

1894 (April 19): Henry Louis Rey died.

1976: As the result of a friendship with Dr. Joseph Logsdon (a professor of history at the University of New Orleans), René Grandjean donated his collection of séance registers, notes, books, photographs, and ephemera to the Special Collections Department, Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The founder and principal medium of Le Cercle Harmonique was Henry Louis Rey. Born in 1831 in New Orleans to a wealthy and prominent Creole family with Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) roots, Rey enjoyed a relatively stable and idyllic childhood and early adulthood. His family was part of les gens de couleur libre (the free people of color) who occupied a middle stratum inserted between the privileged whites and the enslaved blacks prior to the Civil War. Though they lacked political rights, such as the right to vote, free people of color could own property, and make contracts.

His father, Barthélemy Louis Rey, died in 1852, which proved to be a life-changing event for the younger Rey. The excessive expenses for a memorial mass left the family in difficult financial circumstances and engendered a strong dislike for the dominant Catholic Church. The elder Rey’s death coincided with the genesis of Modern American Spiritualism in New Orleans.

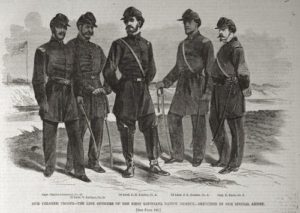

Henry Rey became actively involved with the spiritualist movement that swept the nation in the early 1850s. At first, Rey was a participant and observer, but soon he became recognized for his talents as a medium. The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 resulted in Henry Louis Rey and other free men of color forming the Native Guard, a Confederate military unit to ostensibly aid the Southern causes of slavery and state rights. [Image at right] The fall of New Orleans in May 1862 to the Union, led Rey and fellow officers to offer their services to General Benjamin Butler. In September, a new Native Guard unit was formed, but this time for the Union army. After six months, Rey resigned in Baton Rouge and returned to New Orleans, where he resumed his spiritualist activities.

military unit to ostensibly aid the Southern causes of slavery and state rights. [Image at right] The fall of New Orleans in May 1862 to the Union, led Rey and fellow officers to offer their services to General Benjamin Butler. In September, a new Native Guard unit was formed, but this time for the Union army. After six months, Rey resigned in Baton Rouge and returned to New Orleans, where he resumed his spiritualist activities.

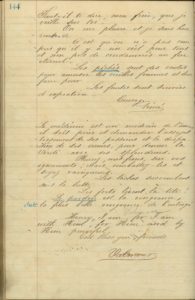

In 1867, Henry Louis Rey formed his séance circle, Le Cercle Harmonique, after Valmour, a charismatic black Creole medium, ceased private and public séances at his home in the New Orleans suburb of Tremé. Rey and his séance participants kept registers in which they recorded communications received from the spiritual  world. [Image at right] According to a contemporary account, the French Creoles “kept a careful record of all its sittings, and of spirit writings received, until their records number many volumes.” The Creole séance circles considered the communications to be sacred texts, and the séance circle members meticulously recorded these messages and carefully preserved the journals in which they were written. However, over time none of these journals survived into the twentieth-first century with the exception of the René Grandjean Séance Registers, housed in the Special Collections Department of the Earl K. Long Library at the University of New Orleans. A careful reading of the spiritual messages and the margin annotations inserted by René Grandjean, the French-born son-in-law of the last living Cercle Harmonique participant, opens a window into the history of the black Creoles, as well as Modern American Spiritualism in the Crescent City (Earl K. Long Library Special Collections website).

world. [Image at right] According to a contemporary account, the French Creoles “kept a careful record of all its sittings, and of spirit writings received, until their records number many volumes.” The Creole séance circles considered the communications to be sacred texts, and the séance circle members meticulously recorded these messages and carefully preserved the journals in which they were written. However, over time none of these journals survived into the twentieth-first century with the exception of the René Grandjean Séance Registers, housed in the Special Collections Department of the Earl K. Long Library at the University of New Orleans. A careful reading of the spiritual messages and the margin annotations inserted by René Grandjean, the French-born son-in-law of the last living Cercle Harmonique participant, opens a window into the history of the black Creoles, as well as Modern American Spiritualism in the Crescent City (Earl K. Long Library Special Collections website).

Most of the spiritual messages were banal communications from the departed to their relatives and friends, assuring them that they had arrived at a better place and were no longer suffering from earthly ailments. The more historically significant messages dealt with social, political, legal, and economic issues that affected the elite black Creoles. Reconstruction was marked by political struggles waged between Union supporters and those who sought a return to the antebellum power system in which wealthy whites controlled the state government. During the late 1860s and the 1870s, the struggles sometimes erupted into epic street battles in New Orleans, which revealed the weak and tenuous hold that Washington had on the Louisiana state government.

The role of the spirit messengers in Le Cercle Harmonique was to encourage its members to continue their noble battle for equality. The official end of Reconstruction in March 1877 signaled the end of their battle and also the end of Henry Louis Rey’s Cercle Harmonique. The last spiritual communication on November 24, 1877, declared that “we are with you for an eternity.”

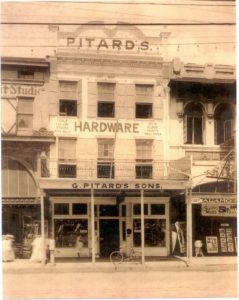

In 1877, Rey returned to work as a clerk in G. Pitard’s Hardware Store [Image at right] on Canal Street after a tumultuous period in public life as a state representative, city tax assessor, and school board member. He continued at Pitard’s until his death on April 19, 1894.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Henry Rey’s circle was a fusion of séance Spiritualism from the North, Afro-Creole radicalism from the Caribbean and France, A. J. Davis’ Harmonial philosophy engendered in the Burnt-Over District of Western New York, and Latin-European Catholicism developed in New Orleans during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The intersection of these philosophies and religions from various points in the world created a unique séance circle in the French faubourgs of New Orleans with its protocols, venues, hallmarks, and progressive social and political agendas. Communications and messengers from the spiritual world reveal the widening ideological chasm between the Americanized version of the Catholic Church and that of a bygone era which had previously supported a fluid tripartite order of races, an era that respected and valued the lives of the Afro-Creoles, an era that no longer existed except in the minds and souls of the former elite free people of color. Deceased Catholic figures descended from the spiritual realm to console and advise the black Creole intelligentsia who gathered weekly at the séance table

Afro-Creole radicalism with its Saint-Domingue and French roots abetted the former free men of color as they attempted to transform the antebellum order into a new egalitarian postbellum order. Rey’s black Creole séance circles set their moral compass with French ideals to navigate the ever-shifting cultural and political currents.

The French Creole séance circles followed the national leadership ofcelebrated mediums from the North such as Emma Hardinge Britten,  Thomas Lake Harris, and the Banner of Light editors. [Image at right] These traveling emissaries of Modern American Spiritualism provided the spark, enthusiasm, support, and framework for séance Spiritualism among the French Creoles who molded northern Spiritualism to fit their linguistic and cultural ethos.

Thomas Lake Harris, and the Banner of Light editors. [Image at right] These traveling emissaries of Modern American Spiritualism provided the spark, enthusiasm, support, and framework for séance Spiritualism among the French Creoles who molded northern Spiritualism to fit their linguistic and cultural ethos.

RITUTALS/PRACTICES

Some of the spiritual communications in the Rene Grandjean Registers detailed a specific protocol for the conducting of séances. [Image at right] Punctuality was essential because latecomers “destroyed the already prepared harmony,” and séances began at either seven o’clock or eight o’clock in the evening, depending on the season. The change in hours was related to the need for darkness. The séance room had to be darkened and quiet so that the participants could concentrate, and spirits would be more receptive to conversing with the living. At the appointed hour, the doors were closed, and the previous communications were read.

detailed a specific protocol for the conducting of séances. [Image at right] Punctuality was essential because latecomers “destroyed the already prepared harmony,” and séances began at either seven o’clock or eight o’clock in the evening, depending on the season. The change in hours was related to the need for darkness. The séance room had to be darkened and quiet so that the participants could concentrate, and spirits would be more receptive to conversing with the living. At the appointed hour, the doors were closed, and the previous communications were read.

The numerous messages from the sympathetic spirits were in the form of letters that were later transcribed, usually by Henry Rey. The message was dated, and at the end was signed by a spirit or sometimes by more than one spirit. Often, the message was addressed to one of the participants. Margin annotations sometimes gave additional information about the spirit, the medium, and the venue.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The medium acted as a conduit between the earthly world and the spiritual world, posing questions collected from the circle and then relaying the responses. Henry Louis Rey provided the leadership for Le Cercle Harmonique, which was actually two circles with different regular members that met on two different days of the week. The regular members numbered seven, an important number for preserving the harmony within the circle.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Le Cercle Harmonique endured the social, political, and economic challenges of the seismic changes of the postbellum years. During the early postbellum years, the tone was cautiously optimistic. But as the years went by, the tone changed to a begrudging acceptance of what Rey referred to as “the oligarchy” and a new lower status for the former free people of color, now facing a devastating leveling of their coveted antebellum status as a superior caste when compared to enslaved blacks, now freedpeople. The circle discussed social reform as something that would happen in the distant future, not as an impending remedy to societal problems. Gone were the strident calls for immediate radical changes and the almost exhilarating visions of a utopian future where the races would be equal socially, economically, and in the eyes of the government. Safely ensconced in their homes, Rey’s séance circles drew closer and more insulated from the ongoing political turmoil raging in the streets and in the halls of the state legislature.

IMAGES

Image #1: Officer of the Union Native Guard.

Image #2: Spiritual Communication from Valmour.

Image #3: G. Pitard’s Hardware Store.

Image #4: Banner of Light masthead.

Image #5: Séance Circle.

REFERENCES

Unless otherwise noted, the material in this profile is drawn from Daggett, Melissa. 2017. Spiritualism in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans: The Life and Times of Henry Louis Rey. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Albanese, Catherine. 2007. A Republic of Mind and Spirit: A Cultural History of American Metaphysical Religion. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Banner of Light (Boston)

Barthet, Joseph. 1857, 1858. Le Spiritualiste de la Nouvelle-Orléans, vols. 1, 2. New Orleans: Joseph Barthet.

Bell, Caryn Cossé. 1997. Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Tradition in Louisiana, 1718-1868. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University.

Braude, Ann. 1989. Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America. Boston: Beacon Press.

Cox, Robert S. 2003. Body and Soul: A Sympathetic History of American Spiritualism. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Daily Picayune (New Orleans).

Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans. René Grandjean Special Collection. Accessed from http://library.uno.edu/specialcollections/inventories/085.htm on 10 June 2017.

Hardinge (Britten), Emma. 1869. Reprint, 1970. Modern American Spiritualism: A Twenty Years’ Record of the Communion Between Earth and the World of Spirits. New Hyde Park, NY: University Books.

Hirsch, Arnold R., and Joseph Logsdon, eds. 1992. Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Hollandsworth, James G., Jr. 1995. The Louisiana Native Guards: The Black Military Experience During the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Post Date:

11 June 2017