USUI REIKI RYŌHŌ TIMELINE

1865: Usui Mikao was born to a merchant family of samurai ancestry in Taniai village (modern Gifu prefecture).

1908: Usui and his wife Sadako (née Suzuki) had a son named Fuji.

1913: The Usuis have a daughter, Toshiko.

c. 1919 (possibly earlier): Usui reportedly began a three-year period of a semi-monastic life at a Kyoto temple.

c. 1922 (possibly earlier): Usui perform ed twenty-one days of austerities on Mt. Kurama, a sacred mountain north of Kyoto, culminating in the mysterious acquisition of the healing powers that became the basis of Usui Reiki Ryōhō.

1922 (April): Usui moved to Tokyo and found ed the Shinshin Kaizen Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai (Mind-Body Improvement Usui Reiki Therapy Society, hereafter Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai) and opened a training facility (dōjō) in Harajuku.

1923 (fall) : Usui dedicated himself to treating the casualties of the Great Kantō Earthquake of September 1.

c. 1925 : Usui opened a larger training facility in Nakano, at that time in the Tokyo suburbs.

c. 1925: Usui’s student Hayashi Chūjirō, a retired captain from the Imperial Navy, opened his own organization called the Hayashi Reiki Kenkyūkai (Hayashi Reiki Research Society) in Shinanomachi, Tokyo.

1926 (March 9): While on a teaching tour in western Japan, Usui died of a stroke in Fukuyama. His student Ushida Juzaburō (1865-1935), a retired rear admiral of the Imperial Navy, became the second president of the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai.

1927: The Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai erected a memorial stele to Usui at Saihōji, Umezato, Suginami-ku, Tokyo.

1935: Ushida died; Taketomi Kan’ichi (1878-1960), also a retired rear admiral of the Imperial Navy who studied Usui Reiki Ryōhō under Usui, became the third president of the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai.

1935 (December): A second-generation Hawaii-born Japanese American, Hawayo Takata (1900-1980), began about six months of studying Usui Reiki Ryōhō at the Hayashi Reiki Kenkyūkai headquarters. The following year, she took Usui Reiki Ryōhō to Hawaii, where it became known as Reiki. By 1951, Takata began teaching on the North American mainland.

1945 (March 9-10): U.S. incendiary bombing raids on Tokyo create d firestorms that killed over 100,000 and left over 1,000,000 homeless. Raids continued into May, and during this period, many of the early records of the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai and Hayashi Reiki Kenkyūkai were likely destroyed.

1946: Watanabe Yoshiharu (d. 1960), a former high school principal who studied under Usui, briefly became the fourth Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai president in the immediate postwar period.

c. 1947: Taketomi Kan’ichi resumed his tenure as Usui Reiki Ryōhō president.

c. 1960: Wanami Hōichi (1883-1975), a former Vice Admiral of the Imperial Navy who studied under Ushida, became the fifth Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai president.

c. 1975: Koyama Kimiko (1906-1999), who studied under Taketomi, became the sixth Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai president.

1984: Mitsui Mieko, who learned Reiki in New York City under Barbara Weber Ray, began to “re-import” Western Reiki (seiyō reiki) back to Japan.

1998: Kondō Masaki (b. 1933), a professor of English literature, became the seventh Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai president.

2010: Takahashi Ichita (b. 1936), a retired businessman, became the eighth Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai president.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

In the early decades of the twentieth century, thousands of Japanese developed therapies that drew on the powers of the mind and spirit to heal physical afflictions. While these therapies emphasized the primacy of mental and spiritual realms (not necessarily considered distinct from each other) over the physical, many of them employed profoundly embodied methods to access these incorporeal realms. For example, many therapists engaged in practices such as abdominal breathing to cultivate an invisible healing power that they transmitted through their hands into the bodies of their patients. These therapies were generally known under the name seishin ryōhō (“psycho-spiritual therapies”) or reijutsu (spirit techniques), and in many ways were akin to the “mind cures” of late nineteenth and early twentieth century North America (Yoshinaga 2015; Hirano 2016).

While examples of these seishin ryōhō survived and even thrived in new religious movements that incorporated under the 1947 constitution (like the jōrei of Sekai Kyūseikyō), the vast majority of these therapies died out during the years of the Pacific War. But one seishin ryōhō from this period flourished in the postwar period without the official status or organizational structure of an incorporated religious body. Usui Reiki Ryōhō (Usui Reiki Therapy, alternately Usui-shiki Reiki Ryōhō or Usui-style Reiki Therapy)  was developed in Japan in the 1920s, adapted for the Japanese American community of Hawaii in the 1930s and 1940s, underwent further modifications for North American audiences in the postwar decades, and grew to global prominence in the late twentieth century under the name Reiki.

was developed in Japan in the 1920s, adapted for the Japanese American community of Hawaii in the 1930s and 1940s, underwent further modifications for North American audiences in the postwar decades, and grew to global prominence in the late twentieth century under the name Reiki.

Usui Reiki Ryōhō takes its name from its founder Usui Mikao, [Image at right] a largely self-taught polymath. The second child and first son of a family that descended from the powerful Chiba clan, Usui was born in the village of Taniai in Yamagata county (modern Gifu prefecture), on the fifteenth day of the eighth month of the first year of the Keiō period, corresponding to October 4, 1865 on the Western calendar. His father was a successful businessman and his grandfather had been a sake brewer (Petter 2012: 31-33). Usui reportedly left his home village at an early age and seldom returned, but he and his three siblings (an older sister, Tsune, and two younger brothers: San’ya, a doctor, and Kun’iji, a policeman) later constructed a stone torii (gate) at a local shrine called Amataka Jinja.

In a stone monument that Usui’s organization erected to memorialize its founder, he is remembered as a man of unusual diligence and broad interests, travelling to China and the West to deepen his studies, which included medicine, psychology, physiognomy, history, Christian and Buddhist scripture, Daoist geomancy, incantation, and divination (Okada 1927). Fukuoka (1974:8) claims that Usui worked a variety of jobs, including as a missionary and a Buddhist prison chaplain, as a public servant, and in private business, but this text is somewhat apocryphal. There are also oral traditions that Usui worked for some time as the private secretary of Gōtō Shinpei (1857-1929), who served as Japan’s foreign minister and home minister, director of Japan’s Colonization Bureau, and the mayor of Tokyo, but the Gōtō Shinpei Organization has been unable to confirm this.

After the collapse of one of his businesses, Usui is said to have “entered the gate of Zen” (zenmon ni hairi), and lived a semi-monastic life for three years, possibly at a temple in Kyoto (Fukuoka 1974:8). There has been speculation that he was affiliated with the Enryakuji monastic complex of Tendai Buddhism, although there is currently little evidence for this. This period of Buddhist practice culminated in three weeks of austerities on Mt. Kurama, a site north of Kyoto associated with mountain asceticism. Usui later said that his twenty-one days of fasting and meditation culminated in a mystical experience in which he was “mysteriously inspired after being touched by the ether,” causing him to “accidentally realize the spiritual [or mysterious] ability to heal disease” (taiki ni furete fukashigi ni reikan shi, chibyō no reinō o eta koto o gūzen jikaku shita, “Kōkai Denju Setsumei”).

Usui’s life history resembles those of other founders of spiritual therapies and new religious movements at this time. His great interest in medicine and religion of both Eastern and Western origin establishes him as an exceptional seeker of new truths regarding human potential for happiness. His spiritual awakening following a period of material hardships, including a failed business, monastic discipline, and ascetic practice on a sacred mountain, is a conventional theme in founder stories. It was likely Usui’s inspiration from a mysterious direct experience, along with his profound, if short, career as a healer and teacher, that caused his eulogist to compare him to the “sages, philosopher, geniuses, and great men” of ancient times and the “founders of religious sects” (Okada 1927). Yet, despite these similarities, the one text attributed to Usui insists that Usui Reiki Ryōhō is a wholly “original therapy” (dokusō ryōhō), not learned from any teacher but “mysteriously” and “accidentally realized” directly from the cosmos (“Kōkai Denju Setsumei”).

Usui only taught for four years before his untimely death in 1926, but in that time he is said to have taught about two thousand students all over Japan. He established the Shinshin Kaizen Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai (Mind-Body Improvement Usui Reiki Therapy Society, hereafter Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai) when he opened his first dōjō (training center) in April 1922, in Harajuku, Tokyo (Okada 1927). He may have chosen to establish his dōjō in Harajuku to be close to the recently completed Meiji Shrine (Meiji Jingu) that enshrined the spirits of the Meiji Emperor and Empress, as formal recitation of and reflection on the Meiji Emperor’s poetry (gyosei) is an foundational practice of Usui Reiki Ryōhō (described in the rituals/practices section below). Usui’s memorial recounts that the entrance to his dōjō “overflowed with shoes,” testament to the great numbers who came in search of instruction and treatment (Okada 1927).

A number of details indicate a possible connection between Usui’s rapid success and the 1921 state suppression of the new religious movement Ōmoto. At that time, Ōmoto had grown to national prominence under its flamboyant leader, Deguchi Onisaburō (1871-1948), and his mediated spirit possession practice called chinkon kishin, which was used for healing purposes, among other things. This practice attracted hundreds of thousands of followers to Ōmoto in the years leading up the “first Ōmoto incident” of 1921, in which Deguchi and other Ōmoto leaders were arrested for lèse-majesté, and chinkon kishin is recognized as playing an important role in precipitating this “incident.” (Staemmler 2009:224-39). In the spirit of other popular religious movements of the early twentieth century, chinkon kichin can be considered a “democratized” spiritual practice, previously the purview of ritual specialists like yamabushi (mountain ascetics) and miko (shrine maidens), but now authorized for use by members of a new religious movement (Hardacre 1994). It could be said that Usui Reiki Ryōhō (among other seishin ryōhō) similarly democratized healing and empowerment practices previously performed by religious professionals such as yamabushi and Buddhist monks. Jonker (2016:331) goes so far as to suggest that Usui Reiki Ryōhō ‘s reiju ritual seems to be an adapted form of chinkon kishin or the related miteshiro otoritsugi, but I am sceptical of so direct of a link. Regardless, the timing of Usui’s rising popularity in the immediate aftermath of Ōmoto’s suppression suggests that some proportion of Usui’s followers may have been former Ōmoto members looking for a new, less politically risky way to connect with the spiritual world for healing. That Ōmoto had been popular among naval personnel and a number of Usui’s top disciples were high-ranking naval officers lends further support to this supposition. Furthermore, the charges that Ōmoto leaders committed lèse-majesté suggest political expediency as a possible factor in Usui’s emphasis on the Meiji Emperor as a spiritual inspiration (Stein 2011).

Usui’s memorial relates that the Great Kantō Earthquake of September 1, 1923, was a turning point in his career, as he treated an uncountable number of casualties from this earthquake and the subsequent firestorms that swept through Tokyo and Yokohama (Okada 1927). Oral tradition claims that Usui received official recognition from the Taishō state for his great efforts in the wake of this natural disaster, but there is currently no evidence corroborating this. Usui’s new fame rendered the Harajuku dōjō too small and he opened a new headquarters in Nakano, then a suburb of Tokyo, in 1925 (Okada 1927). Usui made teaching tours around Japan and in March 1926, he was on such a trip in western Japan, including Hiroshima and Saga, when he suffered a stroke in Fukuyama and died. According to the local way of calculating age, he was sixty-two, but by Western calculations he was sixty.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Unlike many, if not most, of their contemporary reijutsuka and seishin ryōhōka (spiritual practitioners and psycho-spiritual therapists) in pre-war Japan, the leadership of Usui Reiki Ryōhō hardly described any of their beliefs and practices in writing. This was at least partly by design. Usui and his top disciples discouraged their students from writing publicly about Usui Reiki Ryōhō, including advertising their treatments and classes. This is verified in one of the rare public records from the early years of the therapy, a newspaper article by the celebrated playwright Matsui Shōō, who studied under Usui’s disciple Hayashi Chūjirō. In the opening section of this article, Shōō writes, “Despite being able to heal all diseases with a single hand, this therapy is still hardly known to the public. For some reason, Usui especially disliked making it public, so those trained in his schools also still avoid advertising” (Matsui 1928).

This is related to the fact that, like other traditional Japanese arts, the practice of Usui Reiki Ryōhō is taught directly from master to disciple through “secret transmission” (hiden). A group of masters collectively evaluate students’ progress, formalized in a series of ranks. For example, only advanced practitioners who have reached the level called okuden (“inner transmission”) learn the three symbolic forms (not to be revealed to others) that make possible distance treatment. Other rituals are to performed only by practitioners granted the level of shinpiden (“mystery transmission”). Thus, these practices and their associated beliefs are not recorded in any depth in historical written publications, although Reiki’s recent popularity has led to numerous publications and websites that claim to reveal the practices of the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai (see, for example, Doi 1998; Petter 2012).

In addition to this reluctance to put their beliefs and practices into writing, another possible reason for the scarcity of written materials from the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai, the Hayashi Reiki Kenkyūkai, and their membership is the presumed incineration of both organizations’ headquarters in the Tokyo air raids of 1945. It is likely that there was literature at the time that did not survive the war or is being held in a private collection. Finally, as much of the literature produced by the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai and Hayashi Reiki Kenkyūkai was meant for members only, it is possible that leaders of the current Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai possess documents that more clearly explicate the beliefs and practices of Usui Reiki Ryōhō, but are not revealing them to the public.

Regardless, the documents that do remain reveal a number of beliefs at the core of Usui Reiki Ryōhō. One of these beliefs posits the existence of a cosmic force called reiki that individuals can manipulate to enact physical healing, improve bad habits, achieve spiritual development, and generally achieve physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual well-being. The exact nature of this reiki remains somewhat mysterious. Usui is recorded as saying that he learned his therapy “accidentally” when “mysteriously inspired” by “being touched by an ether (taiki)” on Kurama-yama, so “although I am the founder, it is difficult for me to clearly explain [the essence of reiki and the operation of his Reiki Ryōhō]” (“Kōkai Denju Setsumei”). There is a clear legacy from early modern shūyō (self-cultivation) practices in that Usui’s practices are described as “correcting heart-minds through people’s innate [literally ‘heavenly-given’] mysterious abilities” (tenpu no reinō ni yorite kokoro o tadashiku shi, Okada 1927). This continuity is also present in that seishin ryōhō, including Usui Reiki Ryōhō, posit causal relationships between the state of the heart-mind (kokoro) and physical health. When asked what his therapy entails, Usui is said to have replied: “To walk the path of righteousness (seidō), first heal your heart-minds (kokoro o iyashi) and your bodies will become healthy as well” (“Kōkai Denju Setsumei”).

Like other seishin ryōhō of its time, Usui Reiki Ryōhō combines the ideal of self-cultivation (shūyō) with the expansive sense of rei (spirit) developed in the first decades of the twentieth century. While Yumiyama (1999:91-98) describes how a number of contemporaneous new religions, notably Ōmoto, replaced kokoro (heart-mind) with rei, Usui Reiki Ryōhō clearly discusses a relationship between reiki and kokoro, although the nature of the former term remains a bit obscure. In addition to the meaning of an individual spirit (tamashii), the character rei can also signify several other concepts, including the mental, the emotional, the miraculous, and the mysterious. Thus, while reiki is often glossed as “universal life force energy” or “spiritual energy,” the truth is that no extant text from the pre-war period adequately addresses the meaning of the rei in reiki and it is likely that translating compounds that contain rei (such as reinō [mysterious or miraculous abilities] or reiyaku [miracle drug]) solely in reference to “ spiritual ” is somewhat misleading.

As the term reiki was often used by seishin ryōhōka synonymously with terms like seiki (“vitality”), prana (a Sanskrit word for vital energy), and aura, or to translate prana or aura into Japanese, we can assume that “ vital force ” was at least one of reiki ‘s meanings (Hirano 2016:80). Reiki was also used to mean “ positive energy,” in contrast to ‘negative energy’ (jaki), as in the dualistic theory of Tamari Kizō (1912), which was widely-known within the world of seishin ryōhō and referenced by other contemporary therapists. Because of the existence of various other reiki therapies (reiki ryōhō), such as Takagi Hidesuke’s Jintai Aura Reiki-jutsu (Human Body Aura Reiki Techniques) and Watanabe Kōyō’s Reiki Kangen Ryōin (Reiki Restoration Therapy Center), Usui needed to distinguish his therapy, branding it with his name and introducing some innovative practices (Mochizuki 1995:23).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

As with the beliefs associated with Usui Reiki Ryōhō, the history of its practices is only fragmentarily documented. Furthermore, as the current Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai does not permit members to describe its practices to non-members to evade possible  misunderstandings, I am unable to write much here regarding this subject. However, there are a few things that can be stated regarding the historical record of Usui Reiki Ryōhō practice in Japan.

misunderstandings, I am unable to write much here regarding this subject. However, there are a few things that can be stated regarding the historical record of Usui Reiki Ryōhō practice in Japan.

First, Usui’s memorial stone, erected in early 1927, [Image at right] sheds some light on some practices considered central at the time of his death. After saying that Usui Reiki Ryōhō’s purpose was not to merely cure illness and provide healthy bodies, but also to help people correct their heart-minds and attain well-being, it outlines Usui’s teaching: “First, observe the teachings of the Meiji Emperor and, morning and evening, recite the five precepts and engrave them deeply on your heart-mind (kokoro ni nen zeshimu).” Later it says this recitation is to be practiced in the seiza gasshō position, kneeling silently with palms pressed together at chest height (Okada 1927).

The phrase “teachings of the Meiji Emperor” is vague, but probably references the Emperor’s poetry called gyosei, 125 of which are reproduced in the Reiki Ryōhō Hikkei, the handbook distributed to Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai members. These poems treat a variety of themes, but determined self-cultivation is a common trope. A representative example is, “With dust, even a jewel without the slightest flaw can lose its sparkle” (isasaka no kizunaki tama mo tomosureba chiri ni hikari o ushinainikeri). While reciting moralizing poetry for self-cultivation was not in itself an innovative practice, the recitation of these particular gyosei is a distinctive attribute of Usui Reiki Ryōhō.

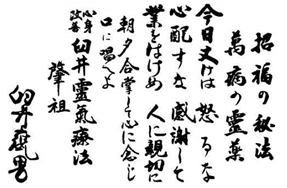

The “Five Precepts” (gokai) referenced by the memorial stone is a short text attributed to Usui, but actually derives from the“Conduct Song” (shosei no uta) composed by the earlier seishin ryōhōka Suzuki Bizan (given name Suzuki Seijirō, dates unknown). In his Kenzen Tetsugaku (Health Philosophy), a synthesis of practices from neo-Confucian self-cultivation and those from Christian Science and New Thought, Suzuki outlined these five preceptsx to be recited daily: “Today only, do not anger, do not fear, be honest, fulfil duties, be kind to  vosorezu, shōjiki ni, shokumu o hagemi, hito ni shinsetsu ni, Suzuki 1914:27). In comparison, a calligraphy signed by Usui reads: [Image at right]

vosorezu, shōjiki ni, shokumu o hagemi, hito ni shinsetsu ni, Suzuki 1914:27). In comparison, a calligraphy signed by Usui reads: [Image at right]

“The secret method of summoning happiness, the miracle drug of all disease: Today only, do not anger, do not worry, be grateful, fulfil duties, be kind to people” (shōfuku no hihō, manbyō no reiyaku, kyō dake wa, ikaruna, shinpai suna, kansha shite, gyō o hageme, hito ni shinsetsu ni).

The memorial stone contains a similar text which it makes clear should be recited twice daily, while in seiza gasshō (silently kneeling with palms pressed together at chest height). “Reciting the five precepts,” it says, “will engrave them in your heart-mind” (gokai o tonaete, kokoro ni nen-zeshimu). It continues, “when you recite [these words] morning and evening, in seiza gasshō, you nurture a humane and healthy heart-mind, and see the joy of daily practice” (seiza gasshō asa-yu nenju no sai ni junken no kokoro o yashinai, heisei no okonai ni fuku seshimuru ni ari, Okada 1927).

Usui Reiki Ryōhō was not the only seishin ryōhō to combine Suzuki’s Kenzen Tetsugaku with vitalistic teate (hand-healing, pronounced “tay-ah-tay”). For example, the Jintai Aura Reiki-jutsu (Human Body Aura Reiki Techniques) created by Takagi Hidesuke around the same time Usui developed his Reiki Ryōhō, contains many practices that closely resemble Usui Reiki Ryōhō, including a five-fold recitation that more closely resembles Suzuki’s formulation than Usui’s gokai, although it is unclear whether Usui or Takagi directly influenced one another (Takagi 1925; Hirano 2016:81).

A number of Usui and Hayashi’s students agree that gokai and gyosei recitations were the basis of Usui Reiki Ryōhō’s efficacy and what distinguished Usui’s methods from those of other practitioners. Tomabechi Gizō (1880-1959), an industrialist-turned-politician who had studied under Usui, listed recitation of the gokai in the morning and evening as the first of a series of “health methods” in his memoir (Tomabechi and Nagasawa 1951:335). Tomita Kaiji, another student of Usui who went on to found his own reiki therapy, taught a practice called jōshin-hō (“heart-mind purification method”) in which practitioners sit in the seiza gasshō position described above, reading the gyosei in their kokoro (“heart-mind”). Regular practice, Tomita writes, will “more and more purify the spirit (seishin)” as “the emperor’s kokoro expressed in the gyosei illuminates one’s own kokoro ” (1999 [1933]:63). And Yamaguchi Tadao, whose mother was trained by Usui’s student Hayashi Chūjirō, writes that the recitation of gokai and gyosei “distinguished [Usui Reiki Ryōhō] practitioners from other healers” (2007:79). As previously mentioned, there were literally thousands of other seishin ryōhō at the time, including several others called reiki ryōhō, so distinguishing characteristics would have been key to the success of Usui Reiki Ryōhō.

The recitation of the gyosei and gokai was the foundation for other meditation practices to purify the kokoro as well as practices to channel reiki through the hands, breath, and eyes. Advanced practitioners were taught to project reiki to a distant recipient, often using his or her photograph. These channeling practices are thought to heal bodies of physical maladies, as well as to “correct bad habits” (akuheki o kyōsei), including worry (hanmon), weakness (kyojaku), indecision (yūjūfudan), and nervousness (shinkeishitsu) (“Kōkai Denju Setsumei”). In order to perform techniques including distance treatment (enkaku ryōhō) and treatment of bad habits (seiheki), advanced practitioners learn three symbols to be traced or visualized, and not to be disclosed to the uninitiated. The first symbol, which increases the amount of reiki flow, seems to derive from Shintō/Daoist sources, the second, used in correcting bad habits, is related to Sanskrit character hrīḥ (Jp., kiriku), associated with Amida Buddha, and the third is a talisman based on five Chinese characters, including the compound shōnen, which in Buddhist contexts means “right mindfulness,” one of the steps of the Eightfold Path.

These techniques are taught in a succession of levels, with more gradations than the three-fold system of First Degree, Second Degree, and Master Degree common to most contemporary forms of Reiki practice. Also, whereas most contemporary Reiki practice, in which Reiki Masters perform initiations for each degree once, rarely or never repeating them (see Beeler and Jonker 2016 ), chapters of the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai and the Hayashi Reiki Kenkyūkai practiced a ritual called reiju (“bestowing reiki ”) at every meeting. Horowitz (2015) argues that this ritual is derived from the esoteric Buddhist kanjō initiation, itself derived from ablution and empowerment rituals of Indic origin called abhiṣekha. The centrality and periodicity of this ritual to Usui Reiki Ryōhō is evident in the fact that pre-war chapters of the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai and Hayashi Reiki Kenkyūkai referred to their meetings as reijukai (reiju meetings). There is no one clear explanation of this ritual’s meaning, but it could constitute a technique by which the individual is connected to the cosmic source of reiki, ritually re-enacting Usui’s experience on Mt. Kurama.

The hand-healing method (teate ryōhō) of the pre-war Usui Reiki Ryōhō seems to have predominantly used one hand, whereas  most contemporary Reiki lineages teach the use of two hands. [Image at right] This is evident in the articles published in the March 4, 1928 issue of Sunday Mainichi written by Matsui Shōō (1870-1933) a playwright who had studied under Hayashi) and by an anonymous patient of Matsui, who outlines how his treatment experience transformed him from a skeptic to a hesitant believer. Matsui refers to Usui Reiki Ryōhō as “a therapy that heals all disease with a single hand” (sekishu manbyō o jisuru ryōhō), and his patient also refers to it as “single-hand therapy” (sekishu ryōhō). The patient describes how Matsui’s right hand became so painful during the treatment that he had to change it for his left (Matsui 1928). The projection of “ki and light” (“Kōkai Denju Setsumei”) in this “single-hand therapy” closely resembles the practices of jōrei and okiyome used by various new religious movements including Sekai Kyūsei-kyō and Mahikari. These movements explain their practices’ efficacy more in terms of purity and pollution than Usui Reiki Ryōhō (Stein 2012).

most contemporary Reiki lineages teach the use of two hands. [Image at right] This is evident in the articles published in the March 4, 1928 issue of Sunday Mainichi written by Matsui Shōō (1870-1933) a playwright who had studied under Hayashi) and by an anonymous patient of Matsui, who outlines how his treatment experience transformed him from a skeptic to a hesitant believer. Matsui refers to Usui Reiki Ryōhō as “a therapy that heals all disease with a single hand” (sekishu manbyō o jisuru ryōhō), and his patient also refers to it as “single-hand therapy” (sekishu ryōhō). The patient describes how Matsui’s right hand became so painful during the treatment that he had to change it for his left (Matsui 1928). The projection of “ki and light” (“Kōkai Denju Setsumei”) in this “single-hand therapy” closely resembles the practices of jōrei and okiyome used by various new religious movements including Sekai Kyūsei-kyō and Mahikari. These movements explain their practices’ efficacy more in terms of purity and pollution than Usui Reiki Ryōhō (Stein 2012).

LEADERSHIP/ORGANIZATION

For about a half-century after Usui’s death, the central leadership of the Shinshin Kaizen Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai was composed of officers of the Imperial Navy. By 1926, twenty of Usui’s students had attained the rank of shihan (instructor), three of whom were naval officers. The rear admirals Ushida Juzaburō (1865-1935) and Taketomi Kan’ichi (1878-1960), respectively served as the second and third presidents (kaichō) of the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai. The third, naval captain Hayashi Chūjirō, started his own organization, the Hayashi Reiki Ryōhō Kenkyūkai (Hayashi Reiki Therapy Research Society), which served an important role in the transmission of Usui Reiki Ryōhō to the West. The Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai’s fifth president, Wanami Hōichi (1883-1975), was a former Vice Admiral who studied under Ushida. The centrality of officers from the Imperial Navy changed in 1975 with the installation of the long-serving sixth president, Koyama Kimiko (1906-1999), who studied Usui Reiki Ryōhō under Taketomi Kan’ichi with her husband, a sociology professor. Thus, except for a period of a few months in the immediate aftermath of the war, the top leaders of the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai were former naval officers for almost fifty years.

The decline of the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai in the immediate postwar period may well have been precipitated by this close relationship with the Imperial Navy. While the organization had dozens of branches and thousands of members across Japan during the pre-war period, it is in a long period of decline since the end of the Pacific War. The post-war dissolution of the Navy under the 1947 constitution must have negatively impacted the public prestige of the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai leadership and public perception of the organization. This could explain the brief period in 1946 when Watanabe Yoshiharu (d. 1960), a former high school principal who studied Usui Reiki Ryōhō under Usui, became the organization’s fourth president. It is possible that Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai members, with their recitation of the Meiji Emperor’s poetry (described in a following section) and connections to the Imperial Navy, could have been regarded as religious nationalists, and if the organization ever espoused strong nationalism, this tendency has since faded. Either way, the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai’s insularity, which dates to the 1920s (Matsui 1928), seems to have grown even more pronounced during the postwar period, perhaps due to anti-Imperial sentiment during the U.S.-led Occupation, the continued rise of biomedical authority, the establishment of national health insurance, and the growing association of similar forms of healing (like jōrei and okiyome) with controversial new religious movements.

The organization of the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai currently seems to be at a crossroads. The mostly elderly leadership looks back to Koyama’s presidency (c. 1975-1998) as a sort of recent ‘golden age’ that they would like to restore. However, membership has again declined after her retirement in 1998, due to low rates of recruitment and the attrition of elderly members passing away. They have had difficulty recruiting and retaining a new generation of younger Japanese members, despite Japan’s so-called “spiritual boom” of the 2000s. Today only five Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai branches remain, with an official total of approximately five hundred members, although the number who regularly attend meetings is considerably smaller than that. Although the two presidents who have followed Koyama both speak fluent English, and could have established ties to the flourishing international Reiki community that expresses strong interest in “traditional Japanese Reiki,” the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai has only recently begun to admit foreign members, of whom there are a handful.

While the main focus of this article is on Usui Reiki Ryōhō and the Shinshin Kaizen Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai, there are also at least three other groups of related practices in contemporary Japan. The largest of these is those Japanese who practice so-called “Western Reiki” (seiyō reiki), usually simply called Reiki (written in katakana). Western Reiki is the product of the Hawaii-born Japanese American Hawayo Takata [Image at right] (1900-1980), who studied under Usui’s disciple Hayashi Chūjirō at his organization’s headquarters in Shinanomachi, Tokyo, beginning in December 1935. By all accounts, Takata had a close relationship with Hayashi and he is said to have named her his successor just before taking his own life on the brink of the Pacific War in 1940. Over Takata’s forty-five years practicing and teaching, she had over ten thousand students, and she was particularly active on the North American mainland from the mid 1970s until 1980. During this final teaching period, she also trained at least twenty-two Master students (i.e., Reiki instructors).

three other groups of related practices in contemporary Japan. The largest of these is those Japanese who practice so-called “Western Reiki” (seiyō reiki), usually simply called Reiki (written in katakana). Western Reiki is the product of the Hawaii-born Japanese American Hawayo Takata [Image at right] (1900-1980), who studied under Usui’s disciple Hayashi Chūjirō at his organization’s headquarters in Shinanomachi, Tokyo, beginning in December 1935. By all accounts, Takata had a close relationship with Hayashi and he is said to have named her his successor just before taking his own life on the brink of the Pacific War in 1940. Over Takata’s forty-five years practicing and teaching, she had over ten thousand students, and she was particularly active on the North American mainland from the mid 1970s until 1980. During this final teaching period, she also trained at least twenty-two Master students (i.e., Reiki instructors).

Although Takata taught a number of classes in post-war Japan, her form of Reiki, with its modified initiation ceremony and distinctive hour-long ‘foundation treatment’ (twelve hand positions held for five minutes each), does not seem to have really spread in Japan until the 1980s, when Mitsui Mieko (dates unknown) “re-imported” Reiki from the United States. Mitsui became a Reiki Master under Takata’s Master student Barbara Weber (later Barbara Weber Ray) in New York City in the early 1980s and began to teach Reiki in Japan in 1984, publishing a translation of her Master’s book a few years later (Ray 1987). This translation was the first Japanese monograph on the subject of Usui Reiki Ryōhō, although earlier texts exist that describe related practices developed by students of Usui (e.g., Mitsui 1930 [2003]; Tomita 1999 [1933]).

After Western Reiki, the second-largest group of Reiki practitioners in Japan is composed of two lineages headed by students of Yamaguchi Chiyoko (1921-2003) who, like Takata received initiations from Hayashi Chūjirō in the 1930s. Chiyoko’s son, Yamaguchi Tadao (b. 1952), heads a lineage called Jikiden Reiki (Direct Transmission Reiki), and a Jodō-shū (Pure Land Buddhist) monk named Inamoto Hyakuten (b. 1940) heads a lineage called Kōmyō Reiki (Bright Light or Enlightenment Reiki). These lineages were both developed in Japan in the late 1990s and have since acquired worldwide followings.

A third form of Japanese Reiki lineage, known as the Gendai Reiki-hō (Modern Reiki Method), is a hybrid of Usui Reiki Ryōhō and Western Reiki founded by Doi Hiroshi (b. 1935). In the seishin sekai (Spiritual World) milieu of mid 1980s Japan (a cultural movement influenced by the New Age), Doi studied a great number of healing modalities, including Western Reiki in Japan under Mitsui Mieko. In 1993, Doi became an Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai member under the leadership of Koyama Kimiko. In 1995, Doi created the Gendai Reiki Hīringu Kyōkai (Modern Reiki Healing Association) and began teaching Gendai Reiki-hō, which consciously fuses elements of the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai’s practice with those of Western lineages to “integrate Eastern and Western Reiki methods” (tōzai reiki-hō no tōgō, Doi 1998: 54). By means of the Internet, Doi made connections with North American and European Reiki practitioners and became the first significant Japanese teacher to teach outside of Japan since Hayashi’s teaching tour in the Hawaiian Islands in 1937-1938. He was one of the key speakers at the first Usui Reiki Ryoho International conference in Vancouver and continues to travel and teach internationally despite his advanced age.

There is a history of discord, even disdain, among Reiki’s diverse lineages. Among Western Reiki groups, Barbara Weber famously claimed that she alone had been given the complete system by Takata and that Takata’s other Master students had to re-train with her. Today Yamaguchi Tadao makes a similar claim that his mother disavowed Inamoto Hyakuten before her death. And the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai has been largely uninterested in interacting with other lineages for decades, only recently agreeing to accept members who had previously studied Western Reiki. The fact that Doi teaches modified versions of their practices without authorization has not helped matters. Although many Reiki practitioners receive initiation in more than one lineage, and there seems to be movement toward more tolerance of differences in belief and practice, inter-lineage tensions remain and the prospect of a general peace in the immediate future seems unlikely.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

While certain elements of Usui Reiki Ryōhō draw on religious traditions and resemble religious practice, the question of whether it constitutes “a religion” is arguable. The Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai and subsequent Reiki Ryōhō organizations such as the Hayashi Reiki Kenkyūkai rank among the numerous groups in Japan “that developed around a local religious practitioner, such as a diviner or healer who has a number of regular clients and devotees, but that have not coalesced into organized religious groups or sought formal registration as such” (Reader 2015:10-11). To distinguish between such groups and formal religious organizations, Shimazono coined the phrase “new spirituality movements” (shin reisei undō 2004). But, as Bodiford writes regarding the relationship between Japanese martial arts and religion, as “even in Western contexts … the terms religion and spiritual lack consistent and general accepted definitions … it should not be surprising … that their application to Japanese contexts is frequently problematic” (2001:472).

Bodiford’s analysis could be applied to any number of phenomena in Japanese culture, but it is perhaps particularly appropriate to the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai of the pre-war era, which resembled its contemporary martial arts in several ways: its identification with mystical aspects of emperor worship, its connections with the Japanese military ideals of “spiritual education” (seishin kyōiku), the reference to Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai centers as dōjō, an education model that somewhat resembles the ryūha system of traditional arts with its emphasis on hierarchical ranks and familial lineages, and the vows (kishōmon) to protect the esoteric secrets taught to advanced students. As we have seen, many of Usui’s top disciples, including the two presidents who succeeded him, were high-ranking naval officers, and Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai leaders recount that these officers thought that Usui Reiki Ryōhō would be an expedient practice for military personnel to practice.

The Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai today faces an existential challenge. Its dedication to maintaining its traditional practices, including a policy of gradual advancement over years and an unwillingness to advertise to attract new members, is tied to its stagnant membership numbers and aging leadership. While Reiki practitioners I have spoken with, both in Japan and abroad, exhibit great interest in joining the Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai, its structure makes it difficult to join, due to policies requiring the recommendation of a current member and the ability to regularly attend meetings, mostly held in the Tokyo area. As meetings are only conducted in Japanese, significant knowledge of the Japanese language is practically a requirement as well. These policies are seen as safeguards to limit membership to those who are sincere about developing their practice for spiritual cultivation and healing others rather than capitalizing on their status for prestige and material gain. In an age when estimated millions worldwide engage in practices derived from Usui Mikao, and when these international Reiki communities clamor for historically authentic practices, it is somewhat ironic that the organization that has ostensibly preserved the most traditional forms of Usui’s practices struggles to maintain membership numbers due to their very dedication to his principles.

IMAGES

Image #1: Image of Usui Mikao.

Image #2: Usui’s memorial stone.

Image #3: The *gokai *(Five Precepts) in Usui’s hand.

Image #4: Photograph of Reiki hand healing.

Image #5: Photograph of Hawayo Takata.

REFERENCES

Beeler, Dori, and Jonker, Jojan. 2016. “Reiki (West).” The World Religions and Spiritualities Project. Accessed from http://wrldrels.org/profiles/ReikiWest.htm on 18 July 2016.

Bodiford, William. 2001. “Religion and Spiritual Development: Japan.” Pp 472-505 in Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia. Volume 2: R-Z, edited by Thomas A. Green. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Doi Hiroshi. 1998. Iyashi no Gendai Reiki-hō: Dentō Gihō to Seiyō-shiki Reiki no Shinzui (The Modern Reiki Method of Healing: The Essence of Traditional Techniques and Western-style Reiki). Tokyo: Genshū Shuppansha.

Fukuoka Kōshirō. 1974. Reiki Ryōhō no Shiori (Reiki Therapy Guidebook). Tokyo: Shinshin Kaizen Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai (possibly apocryphal, as the contemporary organization repudiates this publication).

Hardacre, Helen. 1994. “Conflict Between Shugendō and the New Religions of Bakumatsu Japan.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 21:137-66.

Hirano Naoko. 2016. “The Birth of Reiki and Psycho-spiritual Therapy in 1920’s-1930’s Japan: The Influence of ‘American Metaphysical Religion.’” Japanese Religions 40:65-83.

Horowitz, Liad. 2015. האזוטרי ויהקאנג טקס של מודרני כגלגול הרייקי חניכת : וסודות סמלים,טקסים (“Rituals, Symbols, and Secrets: The Reiki Initiation Ceremony as a Modern Incarnation of Esoteric Kanjō ”). M.A. Thesis, Tel Aviv University.

Jonker, Jojan. 2016. Reiki: The Transmigration of a Japanese Spiritual Healing Practice. Zurich: Lit Verlag.

“Kōkai Denju Setsumei” (Public Explanation of Instruction). 1922. In Reiki Ryōhō Hikkei (Reiki Therapy Handbook). Tokyo: Shinshin Kaizen Usui Reiki Ryōhō Gakkai. Accessed from http://www.reiki.or.jp/j/4kiwameru_5.html on 12 May 2016.

Matsui Shōō. 1928. “Sekishu Manbyō o Jisuru Ryōhō” (Therapy that Heals All Disease with a Single Hand). Sunday Mainichi, March 4, 14-16.

Mitsui Kōshi. 1930 [2003]. Te-no-hira Ryōji (Palm Healing). Tokyo: Vorutekksu Yūgen Kaisha.

Mochizuki Toshitaka. 1995. Iyashi no Te: Uchū Enerugī ‘Reiki’ Katsuyō-hō (Healing Hands: The Practical Use of “Reiki” Universal Energy). Tokyo: Tama Publishing.

Okada Masayuki. 1927. Reihō Chōso Usui Sensei Kudoku no Hi (Memorial of the Merit of Usui-sensei, Founder of the Spiritual Method). Transcribed at and accessed from http://homepage3.nifty.com/faithfull/kudokuhi.htm on 12 May 2016.

Petter, Frank Arjava. 2012. This Is Reiki: Transformation of Body, Mind and Soul – From the Origins to the Practice. Twin Lakes, WI: Lotus Press.

Ray, Barbara Weber. 1987. Reiki Ryōhō – Uchū Enerugī no Katsuyō, trans. Mitsui Mieko, Tokyo: Tama Publishing. [Originally published as The Reiki Factor: A Guide to Natural Healing, Helping, and Wholeness (Smithtown, NY: Exposition Press, 1983)].

Reader, Ian. 2015. “Japanese New Religions: An Overview.” The World Religions and Spirituality Project. Accessed from http://www.wrs.vcu.edu/SPECIAL%20PROJECTS/JAPANESE%20NEW%20RELIGIONS/Japenese%20New%20Religions.WRSP.pdf on 12 May 2016.

Shimazono Susumu. 1996. Seishin Sekai no Yukue: Gendai Sekai to Shin Reisei Undō (Whither the Spiritual World? The Modern World and New Spiritual Movements). Tokyo: Tōkyōdō Shuppan.

Staemmler, Birgit. 2009. Chinkon Kishin: Mediated Spirit Possession in Japanese New Religions. Münster: Lit Verlag.

Stein, Justin. 2012. “The Japanese New Religious Practices of jōrei and okiyome in the Context of Asian Spiritual Healing Traditions.” Japanese Religions 37:115-41.

Stein, Justin. 2011. “The Story of the Stone: Memorializing the Benevolence of Usui-sensei, Founder of Reiki Ryoho.” Unpublished paper presented at the International Conference of the European Association for Japanese Studies, Tallinn, Estonia, August 26.

Suzuki Bizan. 1914. Kenzen no Genri (Principles of Health). Tokyo: Teikoku Kenzen Tetsugaku-kan.

Takagi Hidesuke. 1925. Danjiki-hō oyobi Reiki-jutsu Kōgi (Lectures on Fasting Methods and Reiki Techniques). Yamaguchi City: Reidō Kyūsei-kai.

Tamari Kizō. 1912. Naikan-teki Kenkyū: Jaki, Shin-byōri-setsu (Internal Research: Negative Energy, a New Explanation of Pathology). Tokyo: Jitsugyō Oyobi Nihon-sha.

Tomabechi Gizō and Nagasawa Genkō. 1951. Tomabechi Gizō Kaikoroku (Tomabechi Gizō Memoirs). Tokyo: Asada Bookstore.

Tomita Kaiji. 1999 [1933]. Reiki to Jinjutsu: Tomita-ryū Teate Ryōhō (Reiki and Benevolence: Tomita-lineage Hand-healing Therapy). Tokyo: BAB Japan Publishing.

Yamaguchi, Tadao. 2007. Light on the Origins of Reiki: A Handbook for Practicing the Original Reiki of Usui and Hayashi. Twin Lakes, WI: Lotus Press.

Yoshinaga Shin’ichi. 2015. “The Birth of Japanese Mind Cure Methods.” Pp. 76-102 in Religion and Psychotherapy in Modern Japan, edited by Christopher Harding, Fumiaki Iwata, and Shin’ichi Yoshinaga. New York: Routledge.

Yumiyama Tatsuya. 1999. “Rei: Ōmoto to Chinkon Kishin” (Spirit: Ōmoto and Chinkon Kishin). Pp. 87-127 in Iyashio Ikita Hitobito, edited by Tanabe Shintarō, Shimazono Susumu, and Yumiyama Tatsuya. Tokyo: Senshu University Press.

Post Date:

14 November 2016