CONTEMPORARY SERPENT HANDLING SECTS OF APPALACHIA

SERPENT HANDLING SECTS TIMELINE

c. 1880: George Went Hensley was born in Hawkins County, Tennessee.

1886: The Church of God ( Cleveland, Tennessee) originated in a small group meeting of former members of a local Baptist church.

1915: Hensley became a minister in the Church of God ( Cleveland, Tennessee).

1940: The first law prohibiting serpent handling was passed in Kentucky.

1941: Georgia passed a law making serpent handling illegal and classified the offense as a felony.

1945: Hensley and Raymond Hayes founded the “Dolly Pond Church of God with Signs Following” in Ooltewah, Tennessee.

1947 (April): A law prohibiting serpent handling was passed in Tennessee and was later upheld by the Tennessee Supreme Court.

1949–1950: North Carolina (1949) and Alabama (1950) passed laws prohibiting serpent handling.

1955 (July): George Hensley died in Florida after being bitten by a rattlesnake.

2012: Mark Wolford, pastor at the Apostolic House of the Lord Jesus in Matoaka, died after being bitten by a rattlesnake while he was preaching in Jolo, West Virginia.

2014: Jamie Coots, pastor of the Full Gospel Tabernacle in Jesus’ Name in Kentucky, died after being bitten by a timber rattle snake.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The origin of serpent handling sects is disputed. Oral histories of handlers suggest that serpent handling has always occurred in Appalachia (Hood 2005). However, a scholarly consensus is that the origin is attributed to George Went Hensley who likely first handled in the first decade of the twentieth century (Burton 1993). His charismatic career was closely followed by various print media until his death by a serpent bite in 1955 while preaching a revival in Florida. Some scholars claim that serpent handling had independent origins in several Appalachian states in the first part of the twentieth century associated with the rise of Pentecostalism (See Hood and Williamson 2008 for a review). Most contemporary serpent handlers have little knowledge nor interest in its specific history. Their concern is with the practice of serpent handling largely as handed down to them by their families and tradition (Brown and McDonald 2000).

Most scholars attribute the founding of the contemporary serpent handling sects to George Went Hensley, but as Burton (2003) has noted, details of his biography remain elusive. What is certain is that he first handled a serpent on White Oak Mountain in Tennessee in response to Mark16:17-18. He began preaching in support of serpent handling in community churches, brush arbors and in private homes. He joined the Church of God in 1912. Soon his ministry of serpent handling gained the attention of Church of God leaders, and what was to become a major Pentecostal denomination endorsed the practice as one of the signs specified in Mark 16:17-18. In 1922, Hensley resigned his ministerial credentials because of unstated family problems. However, by that time congregations scattered throughout Appalachia and other parts of America practiced handling. Many can be traced to the perambulatory preaching of George Hensley, but others likely emerged independently. As Hood and Williamson (2008) note, all that is needed for serpent handling to emerge is a supportive culture, ready availability of serpents, a commitment to the plain reading of Mark 16:17-18 and someone to model the practice.

has noted, details of his biography remain elusive. What is certain is that he first handled a serpent on White Oak Mountain in Tennessee in response to Mark16:17-18. He began preaching in support of serpent handling in community churches, brush arbors and in private homes. He joined the Church of God in 1912. Soon his ministry of serpent handling gained the attention of Church of God leaders, and what was to become a major Pentecostal denomination endorsed the practice as one of the signs specified in Mark 16:17-18. In 1922, Hensley resigned his ministerial credentials because of unstated family problems. However, by that time congregations scattered throughout Appalachia and other parts of America practiced handling. Many can be traced to the perambulatory preaching of George Hensley, but others likely emerged independently. As Hood and Williamson (2008) note, all that is needed for serpent handling to emerge is a supportive culture, ready availability of serpents, a commitment to the plain reading of Mark 16:17-18 and someone to model the practice.

As some Pentecostal groups endorsed the practice (especially the Church of God and it’s splintered offshoot, the Church of God or Prophecy), other Penntecostal groups opposed the practice. Early beliefs that handlers could not be bitten, or if bitten, not harmed soon proved to be false. The assumption that serpent handling is not highly risky is challenged by empirical data indicating that the probability of a bite due to handling is largely the frequency of handling. Thus early impressions of successful handling were misguided, with scoffers and some researchers believing there was a “trick” involved, the serpents were defanged, frozen, or any number of explanations. Likewise, early believers felt that successful handling (which they identify as “victory”) was due to the protective power of the anointing of the Holy Ghost. However, as churches institutionalized the ritual of handling, bites became more frequent, sometimes with maiming and death as a result. It is likely that many early deaths went unreported. However, newspapers began to report on deaths. The earliest documented death by a serpent bite was that of Cleveland Harrison, which was reported in the Kingsport Times on August 5, 1919 (“Holly Roller” Dies” 1919). By 1930, newspapers began to regularly report bites and deaths. The emerging Pentecostal denominations that once endorsed the practice began to back away and eventually abandoned the practice. Official church histories of the Church of God even denied that they ever endorsed serpent handling ( Conn 1996). However, as Williamson and Hood (2004) have documented using data from the Church of God’s own archives not only did they endorse the practice but it contributed to their early rapid growth. Today what Hood and Williamson have referred to as the renegade Churches of God continue the practice, despite the passing of laws to make handling of serpents illegal.

Most who have tried to piece together the complex history of serpent handling have used newspaper reports of serpent bites and deaths to create what documented history can be achieved (La Barre, 1974). LaBarre”s history has been cited by several scholars such that it has become almost canonical. It asserts that Hensley initiated the practice in the Church of God in Cleveland Tennessee. As bites became more common, the Church of God gradually minimized the practice while renegade churches in the  Appalachian Mountain regions continued to defend the practice. Handlers in Dolly Pond Church of God with Signs Following headed a resurgence handling in Grasshopper Valley, Tennessee in the 1940’s. A fatal bite to Lewis Ford led to legal restrictions and the waning of the practice in Tennessee and other states as laws were passed to ban the practice of serpent handling. Another resurgence emerged in the 1970’s, only to be thwarted by two deaths by poison drinking in Carson Springs. Some argue that another emergence of handling is currently taking place with many third generation handlers now reaching maturity and continuing the practice (Hood and Williamson 2008).

Appalachian Mountain regions continued to defend the practice. Handlers in Dolly Pond Church of God with Signs Following headed a resurgence handling in Grasshopper Valley, Tennessee in the 1940’s. A fatal bite to Lewis Ford led to legal restrictions and the waning of the practice in Tennessee and other states as laws were passed to ban the practice of serpent handling. Another resurgence emerged in the 1970’s, only to be thwarted by two deaths by poison drinking in Carson Springs. Some argue that another emergence of handling is currently taking place with many third generation handlers now reaching maturity and continuing the practice (Hood and Williamson 2008).

However, as noted above, much of the history of serpent handling is oral and largely undocumented. While a few have made efforts to trace the history of contemporary serpent handling, the relevant documentation is weak and much of the history is speculative (Collins 1947; Conn 1996; Hood 2005). Histories culled from newspaper reports have biased the history toward those who managed to attain notoriety, such as George Hensley, or reports of bites that seriously maimed or killed believers (La Barre 1974). Some have combined La Barre’s limited historical work with supplemental materials from oral history (Hood 2005; Hood and Kimbrough 1995; Kimbrough 2002). Furthermore, scholars have noted that despite the fading from public recognition, serpent handling continued even where laws were passed prohibiting the practice (Kimbrough and Hood 1995). The consensus of what limited history we have is that serpent handling has waxed and waned, perhaps peaking in 1940-1945 when some arbor services drew hundreds of believers and observers. Today, there are at least 125 churches, scattered largely, but not exclusively, throughout the Appalachian Mountains. They are small, averaging 25 members. A common misconception is that all members handle serpents, but this is not true. There are several hub churches associated with powerful serpent handling families that do much to sustain the practice. Handlers often intermarry with other handling families, a practice that helps sustain the tradition (Brown and McDonald 2000). Most religious sects, as Holt (1940) long ago noted and as McCauley (1995) recently reminded us, are understudied. This is even more the case with sects that have minimal, if any, written records, which is common with Appalachian mountain religion (McCauley 1995; Hood 2005). The history is best told by tracing the laws against handling (See Issues/Challenges).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Mark 16:17-18 is the foundational text for serpent handlers. In the King James Bible (the only acceptable Bible to handlers), it reads: “17. And these signs shall follow them that believe; In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new  tongues; 18. They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.” Contemporary handlers take the plain meaning of this text to heart. While one sign is conditional (“if”), the other four are perceived as mandates believers must follow. Thus all serpent handling sects practice all the signs, including the drinking of poisons, most commonly strychnine, although Red Lye and battery acid are also not uncommon. The first documented death from poison was V.A. Bishop in 1921 in a church in Texas. His death was reported that year in the Church of God’s Evangel. Due to the lesser frequency of drinking poison and the mixing of what proved to be sub-lethal dosages, deaths from poison are rare. Subsequent to the death of Bishop, Hood and Williamson have documented only 8 additional deaths, the last in 1973 when Jimmy Ray William Sr. and Buford Pack both died from drinking poison in a service in Carson Springs, Tennessee. As a contrast, Hood and Wiliamson have documented at least 91 deaths from serpent bites. Most recently a death occurred on Memorial Day, 2012 when Mark Wolford died from a rattlesnake bite while preaching in Jolo, West Virginia (Hood 2012b). Thus, the total documented deaths from serpent bites is now at least 92, but as noted above, it is likely that many more deaths have occurred but are undocumented.

tongues; 18. They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.” Contemporary handlers take the plain meaning of this text to heart. While one sign is conditional (“if”), the other four are perceived as mandates believers must follow. Thus all serpent handling sects practice all the signs, including the drinking of poisons, most commonly strychnine, although Red Lye and battery acid are also not uncommon. The first documented death from poison was V.A. Bishop in 1921 in a church in Texas. His death was reported that year in the Church of God’s Evangel. Due to the lesser frequency of drinking poison and the mixing of what proved to be sub-lethal dosages, deaths from poison are rare. Subsequent to the death of Bishop, Hood and Williamson have documented only 8 additional deaths, the last in 1973 when Jimmy Ray William Sr. and Buford Pack both died from drinking poison in a service in Carson Springs, Tennessee. As a contrast, Hood and Wiliamson have documented at least 91 deaths from serpent bites. Most recently a death occurred on Memorial Day, 2012 when Mark Wolford died from a rattlesnake bite while preaching in Jolo, West Virginia (Hood 2012b). Thus, the total documented deaths from serpent bites is now at least 92, but as noted above, it is likely that many more deaths have occurred but are undocumented.

Some handlers are aware of the fact that everything after Mark16:8 is considered a later addition to this Gospel (Thomas and Alexander 2003). However, they accept the King James Bible and the longer ending of the Gospel of Mark as authoritative. In addition, they cite other biblical texts such as Luke 10:19 (“Behold I give you power to tread upon serpents…”) as further biblical support for not only handling of serpents but for walking upon them as well.

As part of the Pentecostal tradition, serpent handling sects, split as other Pentecostal groups do on the issue of baptism. The, oneness tradition or water baptizes in the name of the Father, Son, and the Holy Ghost, which they claim is Jesus. Hence, oneness believers are also called Jesus name believers. Other serpent handling sects are called Trinitarian and do not use the name Jesus in their baptisms. Some churches will not allow handlers who accept a different baptism to preach in their churches.

Serpent handling sects have no official or written doctrines. They share a consensus among early Pentecostals that speaking in tongues in initial evidence of possession by the Holy Ghost such that all serpent handlers speak in tongues. Beyond that, all affirm belief in the plain meaning of scripture, especially Mark 16:17-18. Serpent handlers also believe both that both Christ and the apostles handled serpents. They often cite the last verse of the Gospel of Mark to defend this view which states: “And they went forth, and preached everywhere, the Lord working with them, and confirming the word with signs following” (Mark 16:20). However, scholars find no evidence for the handling of serpents among early Christians (Kelhoffer 2000).

Serpent handling churches derive their individual beliefs and codes from their own understandings of the Bible. This, contrary to popular opinion, produces great diversity in beliefs and practices among serpent handlers. However, some generalizations are possible.

Serpent handlers are conservative in dress and demeanor, and all agree that preachers are called to the ministry, not trained for it, and must not be “double married.” None allow women preachers. However, women may testify and practice all the signs. Many males greet one another with a “holy kiss,” which psychoanalytically oriented scholars have interpreted as indicative of as supposed sexual repression. The central ritual of serpent handling is therefore interpreted in terms of phallic symbolism and the classical Freudian Oedipal drama (La Barre 1974). However, more balanced views, while accepting possible phallic significance of the serpent as symbol, assert caution against such overly simplistic explanations for what is a complex religious sect defying any single reductive explanation (Hood and Williamson 2008). Beyond these simply generalizations, wide variations exist in beliefs and practices of serpent handlers based upon individual church understandings of the Bible.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

While fierce independence characterizes the serpent handling sects, there have emerged common practices and procedures scholars recognize as ritual that these sects share in common. Hood and Williamson (2008) identify behaviors that, while not formally scripted, amount to ritual practices that that have gradually emerged among serpent handling sects and can be identified as ritual behavior.

While gathering for service, which occurs at least once weekly, members greet each other, and any visitors present, with warm handshakes and mutual exchanges of conversation; in some churches, bodily embraces and kisses are reserved for the faithful and same-sexed. At the opening of worship, it is standard practice for the pastor or some other designated person to cordially welcome everyone and encourage all to obey God.

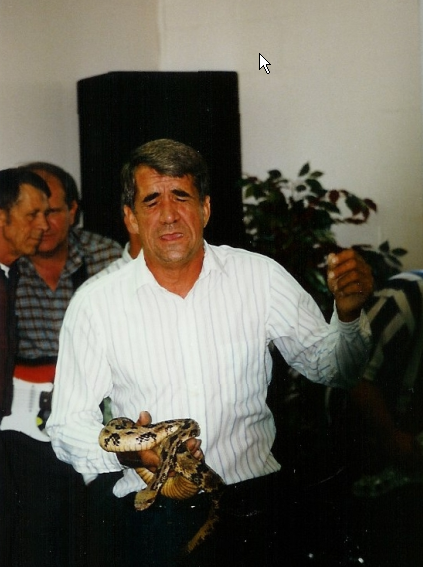

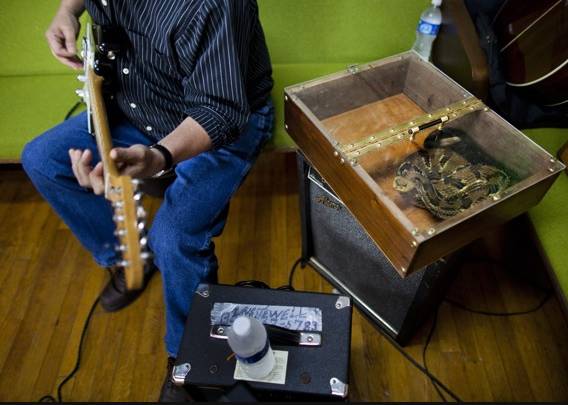

From the front of the church, the leader, most often the pastor, usually announces the presence of serpents that have been brought to church in specially crafted boxes that are resting beside the pulpit. These boxes typically have carved-in biblical references such as Mark 16: 17-18 or a simple phrase of deep meaning to handlers, such as “Wait on God.” Handlers take great pride in the boxes they have made. All contain latches with small paddle locks for protection and safe keeping of the serpents until service begins. It is mostly men who bring serpents to church locked in boxes. Only when they place their serpent boxes down near the altar do they unlock them. In most churches there is a jar of a poisonous solution near the altar. It can be Red Lye or carbolic or strychnine.. To visitors who are present, the reference from the preacher acknowledges what all believers recognize as an ever present fact: “There is death in these boxes. He also often notes that there is “death in this jar,” referring to what most typically is a mason jar with a taped-label that clearly says “poison.” No church is without a small bottle of off-the-shelf purchased olive oil for use in anointing believers for prayer.

After an initial concert prayer, someone begins a song that is then followed by the strumming of guitars, beating of drums, clashing of cymbals, and shaking of tambourines, as others clap hands and join in with expressions of praise to God. With the onset of music, what seems at first to be a cacophonous exhibition soon gives rise to a synchrony of living worship in which believers move freely about and celebrate what is felt to be the presence of God. Suddenly, and without announcement, someone moves toward one of the special wooden boxes, unlatches the lid, and calmly extracts a venomous serpent. As others gather around the activity, participation in worship increases with a more compelling sense of God’s

presence and direction,while other serpents are taken out and passed among the obedient. Amidst these manifestations, another believer passes by others, almost unnoticed, to take the mason jar from the pulpit, remove its lid, and swallow a portion of its toxic contents. The jar is re-secured and quietly returned to its place as the believer takes a moment to worship God in solitude and reverence. When the atmosphere of worship is sensed to have shifted, serpents are returned to their boxes at which time the sick, oppressed, and spiritually needy are offered ministry through prayer and the laying on of hands. At such times, the focus becomes helping others receive what they need from God by personal surrender and obedience to the Spirit. These activities are then followed by special singing, personal testimonies of praise, and extemporaneous sermons that are meant to exhort the righteous, admonish the backslidden, and persuade the unbelieving. As the two-to-three hour service draws to a close, believers fellowship once more, then leave one by one until the next scheduled meeting.

presence and direction,while other serpents are taken out and passed among the obedient. Amidst these manifestations, another believer passes by others, almost unnoticed, to take the mason jar from the pulpit, remove its lid, and swallow a portion of its toxic contents. The jar is re-secured and quietly returned to its place as the believer takes a moment to worship God in solitude and reverence. When the atmosphere of worship is sensed to have shifted, serpents are returned to their boxes at which time the sick, oppressed, and spiritually needy are offered ministry through prayer and the laying on of hands. At such times, the focus becomes helping others receive what they need from God by personal surrender and obedience to the Spirit. These activities are then followed by special singing, personal testimonies of praise, and extemporaneous sermons that are meant to exhort the righteous, admonish the backslidden, and persuade the unbelieving. As the two-to-three hour service draws to a close, believers fellowship once more, then leave one by one until the next scheduled meeting.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Common to what Deborah McCauley (1955) has termed Appalachian Mountain religion, serpent handlers reject any centralized authority. Preachers are “called” and their authority relies upon their ability to sustain a community of believers. Preachers are not paid and most hold down full time jobs, many associated with coal mining common in Appalachia. Churches support one another as long as they concur on baptism. Thus, believers come from over a hundred miles to support different churches with Jesus name believers and Trinitarian believers supporting their churches, but they often not supportive of one another. Churches tend to schedule meetings so as not to clash with “nearby” churches. Thus, some believers are able to attend church every night. Most churches have annual homecomings, usually over at least three days (most commonly Friday through Sunday). On these occasion believers come from all over to support a single church. Among believers sharing baptismal views, homecomings are schedule so as not to conflict with one another.

Financial support is minimal. Many churches seldom collect offerings, or when they do, give the money to a visiting preacher. Rarely do believers tithe. Most churches are owned, often built by the church members on land long owned and donated by an Appalachian family. Few churches incur any debt and preachers manage to sustain minimal costs such as electricity. Repairs and improvements are typically a cooperative activity of congregation members.

A unique organizational requirement is the obtaining of serpents. Many churches keep sheds in which serpents are housed, fed, and made available for church services. Younger males typically hunt for serpents, and occasionally believers trade serpents. Serpents are readily available in the Appalachian Mountain regions, and among the most common indigenous species are copperheads, rattlesnakes, and water moccasins. All can be deadly, but risk varies with the amount and nature of venom  ejected with any bite. Serpents may be kept over winter in heated sheds, but many churches release their serpents in late fall. In winter, availability of serpents is reduced, with some churches dependent upon visitors from other churches with to provide serpents for a given meeting. Serpents are taken to church is handmade boxes, often crafted with great beauty and with carvings on them such as “Wait on God.” Poison is available on the alter, usually mixed in advance by the preacher and contained in a plain mason jar. Most commonly available is strychnine, but other poisons may be used. When bitten or made ill by poison, drinking members may seek medical help. However, most do not, and church members gather round the stricken believer, pray for him or her, and await God’s will. Most churches have members who recall or have witnessed someone bitten, maimed, or killed by a ritual that remains dangerous and unpredictable in outcome (Bromley 2007; Hood and Williamson 2006; Hood 2012a).

ejected with any bite. Serpents may be kept over winter in heated sheds, but many churches release their serpents in late fall. In winter, availability of serpents is reduced, with some churches dependent upon visitors from other churches with to provide serpents for a given meeting. Serpents are taken to church is handmade boxes, often crafted with great beauty and with carvings on them such as “Wait on God.” Poison is available on the alter, usually mixed in advance by the preacher and contained in a plain mason jar. Most commonly available is strychnine, but other poisons may be used. When bitten or made ill by poison, drinking members may seek medical help. However, most do not, and church members gather round the stricken believer, pray for him or her, and await God’s will. Most churches have members who recall or have witnessed someone bitten, maimed, or killed by a ritual that remains dangerous and unpredictable in outcome (Bromley 2007; Hood and Williamson 2006; Hood 2012a).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

The major issues that have and continue to plague serpent handling churches are legal in nature. In the early reporting of bites and deaths, public concern was raised for the welfare of handlers as well as for the welfare of believers. As maiming and deaths began to be reported in print, legislatures were easily persuaded that serpent handling needed to be banned. In addition, the ability of Appalachian states to pass laws against serpent handling was aided by national publicity, especially reports associated with the endangerment of children. In the early years of serpent handling, children did handle. While there is no documented death of a child dying from handling, a widely circulated photograph of a child touching a serpent added to the media frenzy surrounding serpent handling churches in the late 1930s (Kane 1979; Rowe 1982; Burton 1993). The Hood-Williamson archive contains footage of children handling.

Even more serious was the widely publicized serpent bite of a six-year-old girl, Leitha Ann Rowan. She was bitten as a serpent was passed around her church in rural Georgia. Her mother hid her for 72 hours, but other family members then brought Leitha to the sheriff’s office. Her father, Albert Rowan, and the church pastor, W.T. Lipton, were arrested on charges of assault with intent to commit murder, which the sheriff said would be elevated to murder charges if Leitha died. On the previous day the New York Times (“Snake Bitten Child 1940) had identified the serpent as a “copperhead moccasin” and reported that the sheriff said it had also bitten eight other members.

There were no explicit laws against serpent handling in the United States prior to 1940. The first law against serpent handling was passed in Kentucky in 1940. It was stimulated by a complaint from John Day, of Harlan Kentucky, who was offended when his wife began handling serpents at the Pine Mountain Church of God in Pineville, Kentucky. He had three men arrested for breach of the peace, a common way to discourage handling prior to explicit legislation banning the practice (Vance 1975:40-41). In June, 1940, the Kentucky legislature passed the first and only law against handling serpents in a religious setting. While other states would quickly follow suit, none made reference to religious settings, nor did any include what Kentucky banned: not serpents, but the use of any reptiles in a religious service. The statue was challenged in Lawson v. Commonwealth (“Snake Handlers” n.d.). Tom Lawson and others believers were convicted under the Kentucky statute of displaying and handling serpents (“reptiles”) and then appealed their conviction. In upholding the conviction, the appellate court cited Jones v. City of Opelika, a U.S. Supreme Court decision that affirmed the absolute right to freedom of religious belief but not the constitutional right to religious practice. Lawson v. Commonwealth reveals a zeitgeist that would assure that, with the exception of West Virginia, Appalachian states, in which handling was publicly exposed by the media, found it easy to pass laws against handling. Furthermore, the laws without exception were supported by appellate court decisions (www. Firstamendmencenter.org.madison/wp/content).

Probably the most documented discussion of state laws against serpent handling focuses upon the state of Tennessee. Burton (1993: Chapter 5) has analyzed the history of serpent handling in the Tennessee courts and also has produced two documentary films with the assistance of Thomas Headley on the practice serpent handling and legal action, primarily following deaths at Carson Springs discussed below (Burton and Headley 1983, 1986). J. B. Collins (1947), a reporter for the Chattanooga News Free Press documented serpent handling at the church in Dolly Pond, just outside the city of Chattanooga. Tennessee is interesting because, in its two appellate court decisions upholding laws against serpent handling, one was a criminal conviction while the other was a civil conviction.

Tennessee is unique among states with serpent handlers in that one of its local newspapers is linked to the family that owns the New York Times. Thus, much of the media coverage of serpent handling reached a wide audience as the New York Times often carried articles of handling, especially when associated with bites and death. The local Chattanooga papers, the Chattanooga Free Press and the Chattanooga Times, also carried many articles on serpent handling both at Dolly Pond and later at Carson City. As typical, the coverage was linked to deaths at these churches.

In 1945, Lewis Ford was bitten at the Dolly Pond Church of God with Signs Following church just outside Chattanooga, Tennessee (Pennington 1945). J. B. Collins (1947:17) wrote that over 2,500 people attended Ford’s funeral at Dolly Pond. Other deaths occurred in the same year, but not at Dolly Pond. The deaths were reported in the New York Times (“Tennessee Preacher” 1945). While handling serpents in a home in Daisy, Tennessee, Clint Jackson was fatally bitten (Collins 1947:23). In Cleveland, Tennessee, the home of the international headquarters for the Church of God, and just thirty miles from Chattanooga, eighteen year-old Harry Skelton was bitten and died. His death was reported in the Chattanooga Times (“Snake Bite” 1946). Five days later Walter Henry, handling the same serpent that killed Skelton was fatally bitten. Fred Travis wrote of these deaths in the Chattanooga Times (Travis 1946). Finally, to continue this saga of deaths from serpent bites within a brief two year period, Henry’s own brother-in-law, Hobert Williford, handled a serpent at Henry’s funeral, was bitten, and also died. The Chattanooga Times carried the story under the heading, “3 rd Snake Cultist Dies in Cleveland” (1946).

The massive publicity surrounding the handling at Dolly Pond and in Cleveland, Tennessee, as well as the deaths from serpent bites in surrounding states, made it easy for legislatures in Tennessee to propose a bill banning handling. Tennessee’s law was not modeled after Kentucky’s, and the Tennessee law, not Kentucky’s, became the model that other states would follow. Tennessee’s law made no reference to religion. It simply made it illegal to “exhibit, handle, or use any poisonous or dangerous snake or reptile in such a manner as to endanger the life or death of any person” (“Snake Handlers” n.d.). A second difference from the Kentucky law is that specific reference is to snakes or reptiles that are dangerous. The law made handling a misdemeanor punishable by a fine from 50 to 100 dollars or six months in jail, or both (Burton 1993:75).

The Tennessee law was challenged by believers at Dolly Pond, who, despite the law being passed April of 1947, continued to handle serpents. Publicity surrounding Dolly Pond (some after the publicity referred to it as “Folly” Pond) made it an easy target for enforcement of the new law. In August, 1947, Tom Harden, five female handlers, and six other male handlers were arrested. All but one were convicted. Upon appeal to the Tennessee State Supreme Court, the decision of the lower court was upheld. As Burton (1993:80-81) notes in his discussion of this case, two issues were asserted by the court: (a) the practice is inherently dangerous; and hence, (b) the state has an overriding interest such that, while religious belief is protected, the religious practice of handling is constitutionally denied. As we shall see shortly, Tennessee judges would vary in whether that the phrase “any person” in the Tennessee law was absolutely inclusive and thus included the handler, or that it was to be interpreted as “any other person” thus excluding the handler. The difference would become significant when Tennessee civil law was applied to two deaths at the Carson Springs church in East Tennessee in 1973.

In a well-documented case, two handlers at the Holiness Church of God in Jesus Name in Carson Springs, Tennessee died. The massive publicity surrounding these two deaths paralleled that for Dolly Pond more than a quarter of a century earlier. The pastor of the church, Alfred Ball, and a well known handler and former pastor of the church, Liston Pack, were ordered by the circuit court in Cocke County not to handle serpents. The irony is that the handlers who died, Allen Williams, Sr. and Buford Pack, did handle serpents that day, but died from drinking strychnine, not serpent bites. Neither Tennessee law, nor any other states’ laws banning handling make reference to drinking poison. Both Alfred Ball and Liston Pack were convicted under Tennessee civil (common) law. Despite the conviction, handling continued as documented by Kimbrough and Hood (1995). The district attorney for Cocke County banned both poison drinking and serpent handling at Carson Springs, declaring them to be a “public nuisance.” (ironically, differing amounts: $150 for Pack and $100 for Ball) and given twenty days in jail.

The Court of Appeals of Tennessee found the law declaring handling to be a public nuisance to be “unconstitutionally broad” (Burton 1993:78). The law was modified, allowing consenting adults to handle as long as they did so in a manner not to endanger any other persons. The reasonableness of this modification (in our view) is that consenting adults can (a) handle serpents and (b) be in the presence of those who handle serpents even if they do not wish to handle. This would seem to balance both concerns, that of the absolute freedom of religious belief and that of a conditional freedom to practice one’s religion so long as others are not endangered.

Experienced researchers know that church members and observers are not endangered by others who are handling serpents. There is no documented case of a non-handling member being bit by a serpent handled by another believer. Members and visitors may sit far back, away from the area in which serpents are handled if they so choose. Unfortunately (again in our view), an appeal to the Tennessee State Supreme Court resulted in overturning the appellate court and simply asserted that handling is inherently dangerous, and others present are, at a minimum, aiding and abetting. Thus, both handlers and non-handlers who are observing the practice create, in the Tennessee State Supreme Court’s view, a “public nuisance.” Thus, as with Kentucky, Tennessee has consistently ruled against handlers in the final view. Only Tennessee has successfully challenged handlers on the basis both criminal and civil law. An attempt to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court failed; the court refused to hear the appeal.

Other states have banned serpent handling. Virginia banned handling in the same year as Tennessee, 1947. North Carolina followed in 1949, followed by Alabama in 1950. In all these states the issue is whether handling is dangerous to self (apparently obvious) or to others (e.g., non-handlers). As we have noted above, legislatures and courts have had little real knowledge of serpent handling churches and have a poor basis to judge whether serpent handling is dangerous to others (non-handlers, observers). As noted above, there is no record of a non-handler ever being bitten. Churches take precautions to ensure the safety of those who do not handle, allowing them to be in areas where handlers do not go.

Within the serpent handling tradition occasional efforts by pastors to place restrictions on handling to assure additional safety have failed due to the fierce autonomy of those who handle. Few handlers will accept “regulations” on how they handle. Believed to be moved on by God, no handler would wants God’s will regulated. One effort that failed was briefly known as the “Morris Plan.” Pastor C. D. Morris of The Faith Tabernacle in LaFollete, Tennessee, proposed to rope off an area of the church in which handling would occur. He further proposed there could be only one handler could at a time and that each handler must obtain a serpent from the box, no handler could “hand off” to another person. The effort to impose a structure failed. All efforts to structure handling have consistently failed. The basic rule that cuts across all churches is simply “When you handle, be sure God is in it.”

Other state laws need to be explored in order to illuminate dominant attitudes toward handling. Two states have not only banned handling, but have banned handlers from even preaching their beliefs, something that could be challenged constituitionally (Hood, Williamson, and Morris 2000). Both Georgia and North Carolina have made not simply handling, but the “inducement to handle” a violation of law. After stating that “intentional exposure to venomous reptiles” is illegal, North Carolina’s 1949 law went on to sanction any attempt to “exhort” or use “inducement to such exposure” (Burton 1993:81). The second state to ban serpent handling, Georgia, went furthest of all. Their 1941 law made handling illegal and, unlike most states, made is it a felony. Further they made it illegal to encourage or induce anyone to handle a serpent. Thus, in North Carolina and Georgia even preaching from Mark 16:17-18 could be interpreted as a violation of state law. Further, the Georgia law was extreme in stating that if handling or the preaching of handling (“inducement”) resulted in the death of any person, the guilty person “should be sentenced to death, unless the jury trying the case should recommend mercy” (cited in Burton 1993:81; Hood, Williamson, and Morris 2000). Georgia was unsuccessful in getting convictions under its law (no appellate decisions have occurred), and the law was omitted during the 1968 rewriting of the Georgia state code. However, as with the North Carolina law, it reflects attitudes that not only infringe on religious practice, but on the right to religious belief as well. It is a vacuous claim to state that one can have a religious belief but cannot exercise his or her constitutional right to preach that belief.

A final state, Alabama, deserves consideration here. Not only does it continue to house some significant serpent handling churches, it illustrates the case that even as states create, modify, and repeal laws against serpent handlers, serpent handlers continue to be prosecuted under a variety of other laws. Alabama first banned serpent handling in 1950. Like Georgia, Alabama made handling a felony, and like all states except Kentucky, no reference was made to a church or religious gathering. It simply stated that “Any person who displays, handles, exhibits, or uses any poisonous or dangerous snake or reptile in such a manner as to endanger the life or health of another shall be guilty of a felony” (“Snake Handlers” n.d.). Punishment was to be from one to five years in prison. As with all states, despite laws against handling, the practice continued. Often juries in states where handling had strong sub-cultural support, local authorities refused to press charges and juries refused to convict when case were taken to court. In1953, Alabama revised its law by reducing handling to a misdemeanor, with a penalty of up to six months in jail or a fine of from $50 to $150. In 1975, specific laws against handling were deleted when Alabama rewrote its state code (Hood et al. 2000). However, the appeal of specific laws against handling does not mean handlers cannot be persecuted. Alabama has laws against reckless endangerment (a class A misdemeanor) which bans “conduct which creates a substantial risk of serious physical injury to another person” (“Snake Handlers” n.d.). It also has a menace law (a class B misdemeanor) that states “A person commits a crime of menacing if, by physical action, he intentionally places or attempts to place another person in fear of imminent serious injury” (“Snake Handlers” n.d.). Appellate courts have upheld the application of menacing or reckless endangerment laws to serpent handling. Thus, as with the 1973 Carson City convictions in Tennessee, even without specific laws against serpent handling, other laws, both criminal and civil, can be used to arrest those who try to practice their faith.

As a final consideration of legislation against serpent handling, West Virginia provides the best counter example. West Virginia is the home of several serpent handling churches, some of which have long histories of notoriety. Most famous is the Church of the Lord Jesus in Jolo, in McDowell County, West Virginia. It began with a series of house church meetings conducted by Bob and Barbara Elkins (both now deceased from natural causes) in the late 1940s and was formally established as a church in 1956 with the construction its first church building. Barbara Elkins had begun handling when she witnessed George Hensley handling serpents in West Virginia in 1935 (Brown and McDonald 2000). Because of their receptivity to media, the Jolo handlers became major media figures. Jolo gained added media attention when Barbara Elkin’s daughter, Columbia Gaye Chafin Hagerman received a rattlesnake bite while she handled in the Jolo Church in 1961. Refusing medical treatment, she died at her parents’ home four days later. In an interview with the nationally read magazine, People, Barbara said of Columbia: “She handled snakes quite awhile, and this was the first time she’d been bitten. We asked if she wanted to take us to the doctor, but she said no. She wanted God to do what he wanted with her” (Grogan and Phillips 1989). Media attention focused upon Jolo and handling churches in other parts of West Virginia, such as the Scrabble Creek Church of All Nations located in Fayett County. This church became famous for allowing video of its services, including the widely distributed film, Holy Ghost People (Boyd and Adair 1968).

the home of several serpent handling churches, some of which have long histories of notoriety. Most famous is the Church of the Lord Jesus in Jolo, in McDowell County, West Virginia. It began with a series of house church meetings conducted by Bob and Barbara Elkins (both now deceased from natural causes) in the late 1940s and was formally established as a church in 1956 with the construction its first church building. Barbara Elkins had begun handling when she witnessed George Hensley handling serpents in West Virginia in 1935 (Brown and McDonald 2000). Because of their receptivity to media, the Jolo handlers became major media figures. Jolo gained added media attention when Barbara Elkin’s daughter, Columbia Gaye Chafin Hagerman received a rattlesnake bite while she handled in the Jolo Church in 1961. Refusing medical treatment, she died at her parents’ home four days later. In an interview with the nationally read magazine, People, Barbara said of Columbia: “She handled snakes quite awhile, and this was the first time she’d been bitten. We asked if she wanted to take us to the doctor, but she said no. She wanted God to do what he wanted with her” (Grogan and Phillips 1989). Media attention focused upon Jolo and handling churches in other parts of West Virginia, such as the Scrabble Creek Church of All Nations located in Fayett County. This church became famous for allowing video of its services, including the widely distributed film, Holy Ghost People (Boyd and Adair 1968).

Given the widespread publicity surrounding Columbia’s death in West Virginia, the legislature introduced a bill to ban the practice of serpent handling. Barbara Elkins and others from West Virginia churches testified that they would continue to handle serpents even if a law were passed against the practice. In February, 1963, the West Virginia House of Delegates passed a law that would make the handling of poisonous serpents a misdemeanor. Penalties were to be fines from one the five hundred dollars (“House Okays Ban” 1963). However, publicity surrounding the proposed ban and active support for those sympathetic to West Virginia’s powerful history of churches that endorsed serpent handling eventually won the day. The Senate Judiciary Committee refused to act upon the bill. Since that refusal, West Virginia has made no other efforts to pass legislation against serpent handling. Legal experts differ on the constitutionality of laws that legislate against the practice of serpent handling (www. Firstamendmencenter.org.madison/wp/content).

Recent years have seen some interesting developments in serpent handling that may lead to changes in traditional ritual practice (Duin 2021). In 2014, Jamie Coots, pastor of the Full Gospel Tabernacle in Jesus’ Name in Kentucky, died after being bitten by a timber rattle snake. Coots had been a mentor to Andrew Hamblin, who was Pastor of the Tabernacle Church of God. Hamblin appears to have been deeply affected by Coots’ death. He stated that “Since Jamie died,…I’ve offered a rattler to no one. I am the shepherd, and I am responsible for what happens in this building.” This appears to be part of a growing trend toward handlers seeking medical assistance after being bitten. As Duin (2021) reports, “since Coots’ death, many younger serpent-handling preachers, Hamblin among them, have changed their minds on this defining theological point. She also quotes Ralph Hood, who states that “refusing to call 911 is considered old school, and pragmatism rules. Yes, the Gospel of Mark encourages serpent handling, say younger pastors, but no verse forbids seeking help for serious bites. There also appears to be some interest among handling pastors in opening up their churches to a broader audience and attracting younger parishioners.

REFERENCES

Boyd, Blair and Peter Adair (Producers). 1968. Holy Ghost people [Film]. New York: McGraw-Hill Film.

Brown, Fred and Jeanne McDonald. 2000. The Serpent Handlers: Three Families and Their Faith. Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher.

Burton. Thomas. 2003. “George Went Hensley: A Biographical Note.” Appalachian Journal Summer: 346-48.

Burton, Thomas. 1993. Serpent Handling Believers. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press.

Burton, Thomas and Thomas Headley (Producers). 1986. Following the Signs: A Way of Conflict [Film]. Johnson City, TN: East Tennessee State University.

Burton, Thomas and Thomas Headley (Producers). 1983. Carson Springs: A Decade Later [Film]. Johnson City, TN: East Tennessee State University.

Collins, J. B. 1947. Tennessee Snake Handlers. Chattanooga, TN: Chattanooga News-Free Press.

Conn, Charles W. 1996. Like a Mighty Army: A History of the Church of God (Definitive edition). Cleveland, TN: Pathway Press.

Duin, Julia. 2021. “Appalachian snake handlers put their faith in God—and increasingly, doctors.” National Geographic, February 1. Accessed from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/snake-handlers-appalachia-changing-practices on 25 September 2021.

Grogan, David and Chris Phillips. 1989. “Courting Death, Appalachia’s Old-time Religionists: Praise the Lord and Pass the Snakes.” People 31:82.

Holt, John B. 1940. “Holiness Religion: Cultural Shock and Social Reorganization.” American Sociological Review, 5:740-47.

“‘Holly Roller’ Dies During ‘Faith’ Test.” 1919. The Kingsport Times, August 5, p. 2.

Hood, Ralph W., Jr. 2012a. “Ambiguity in the Signs as an Antidote to Impediments to Godly Love among Primitive and Progressive Pentecostals.” Pp. 21-40 in Godly Love: Impediments and Possibilities, edited by Matthew T. Lee and Amos Yong. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Hood, Ralph W. 2012b. “Mack Wolford Death a Reminder that Serpent Handlers Should Be Lauded for Their Faith.” Washington Post/com 5 June. Accessed from http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/mack-wolfords-death-a-reminder-that-serpent-handlers-should-be-lauded-for-their-faith/2012/06/05/gJQAWDN8FV_story.html on June 5, 2012.

Hood, Ralph W., Jr., ed. 2005. Handling Serpents: Pastor Jimmy Morrow’s Narrative History of His Appalachian Jesus’ Name Tradition. Mercer, GA: Mercer University Press.

Hood, Ralph W., Jr. 2003. “American Primitive: In the Shadow of the Serpent.” The Common Review 2:28-37.

Hood, Ralph W., Jr. 1998. “When the Spirit Maims and Kills: Social Considerations of the History of Serpent Handling Sects and the Narrative of Handlers. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 8(2):71-96.

Hood, Ralph W., Jr. and David Kimbrough. 1995. “Serpent Handling Holiness Sects: Theoretical Considerations.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 34(3): 311-22.

Hood, Ralph W., Jr. and W. Paul Williamson. 2006. “Near Death Experiences from Serpent Bites in Religious Settings: A Jamesian Perspective.” Archives de Psychologie 72:139-59.

Hood, Ralph W., Jr., W. Paul Williamson, and Ronald J. Morris. 2000. Changing Views of Serpent Handling: A Quasi-experimental Study. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 39:287-96.

“House Okays Ban on Snake Rituals.” 1963. Charleston Daily Mail, February 14, p. 1.

Kane, Steven. M. 1987. Appalachian Snake Handlers. Pp. 115-27 in, Perspectives on the South: An Annual Review of Society, Politics and Culture (Vol. 4). edited by James C. Cobb and Charles R. Wilson. New York: Gordon and Breach Science Publishers.

Kane, Steven M. 1979. Snake Handlers of Southern Appalachia. Ph.D. dissertation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University.

Kelhoffer, James A. 2000. Miracle and Mission: The Authentication of Missionaries and Their Message in the Longer Ending of Mark. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Kimbrough, David. 2002 (1995). Taking up Serpents: Snake Handing in Eastern Kentucky. Mercer, GA: Mercer University Press.

Kimbrough, David and Ralph W. Hood, Jr. 1995. Carson Springs and the Persistence of Serpent Handling Despite the Law. Journal of Appalachian Studies 1:45-65.

La Barre, Weston. 1974 (1962). They Shall Take up Serpents: Psychology of the Southern Snake-handling Cult. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

McCauley, Deborah V. 1995. Appalachian Mountain Religion: A History. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Pennington, Charles. 1945. “Ford, Rattler’s Victim, Buried: Flock Handles Snakes in Ritual.” Chattanooga Times, September 9, p. 1.

“Snake Bite is Fatal to Cultist: Another Struck Down By Rattler. 1946. Chattanooga Times, 27 August, p. 9.

“Snake Bitten Child Remains Untreated.” 1940. New York Times, 3 August, p. 28.

“3 rd Snake Cultist Dies in Cleveland.” 1946. Chattanooga Times, 15 September, p. 15.

“Snake Handlers and the Law.” n.d.. Accessed from http://members.tripod.com/Yeltsin/law/law.htm on June 6, 2006.

Thomas, J.C. and K.E. Alexander. 2003. “‘And the Signs are Following:’ Mark 16. 9-20: A Journey into Pentecostal Hermeneutics.” Journal of Pentecostal Theology 11:147-70.

Travis, Fred. 1946. “Bradley Baffled by Snake Problem.” Chattanooga Times, 28 August, p. 9.

Williamson, W. Paul and Ralph W. Hood, Jr. 2004. “Differential Maintenance and Growth of Religious Organizations Based upon High-cost Behaviors: Serpent Handling within the Church of God. Review of Religious Research, 46(2):150-68.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Hood-Williamson Research Archives for the Holiness Serpent Handling Sects of Southern Appalachia at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, Lupton Library, University Archives (Special Collections).

Sacramental Practices and Provisions-First Amendment Center. Accessed from www.firstamendmentcenter.org/madisobn/wp-content/vol4ch4 on September 20, 2012.

Author:

Ralph W. Hood, Jr.

Post Date:

16 October 2012