MUSEUM OF THE BIBLE TIMELINE

1941: David Green was born in Emporia, Kansas.

1964: Steven Green was born to David and Barbara Green.

1970: Greco Products was founded.

1972: Hobby Lobby was founded in Oklahoma City.

1976: Hobby Lobby opened its first stores outside of Oklahoma City.

1981: Steven Green, David Green’s son, became an executive in Hobby Lobby.

2009: Steven Green began developing his collection of antiquities.

2010: Hobby Lobby purchased 5,500 artifacts for $1.600,00million.

2011: Passages debuted at the Oklahoma City Museum of Art.

2012: Passages purchased the Washington Design Center.

2017 (November): The Museum of the Bible opened.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

David Micah Green was born into a poor family in Emporia Kansas on November 13, 1941. The family was so poor that it relied on donations of food and clothing (Solomon 2012). His father was a pastor, and in a strongly religious family, David Green [Image at right] was the  only one of six siblings who did not become a pastor in the conservative Church of God of Prophecy denomination (Grossman 2014). He reportedly was a mediocre student in middle school and high school and subsequently worked as a stock boy at a local McClellan’s General Store. After high school, he served in the Air Force Reserve, worked as a manager at a local TG&Y dime store, and married his high school sweetheart, Barbara (Solomon 2012). The couple had three children, two of whom later became executives in Hobby Lobby. In 1970, David Green established Greco Products, producing miniature picture frames in his garage. Two years later he opened his first Hobby Lobby retail space in Oklahoma City. The Hobby Lobby chain grew quickly: to seven stores by 1975, fifteen stores by 1989, 100 hundred stores by 1995, 200 stores by 1999, and over 500 stores by 2015, and nearly 1,000 stores by 2022 in more than forty states.

only one of six siblings who did not become a pastor in the conservative Church of God of Prophecy denomination (Grossman 2014). He reportedly was a mediocre student in middle school and high school and subsequently worked as a stock boy at a local McClellan’s General Store. After high school, he served in the Air Force Reserve, worked as a manager at a local TG&Y dime store, and married his high school sweetheart, Barbara (Solomon 2012). The couple had three children, two of whom later became executives in Hobby Lobby. In 1970, David Green established Greco Products, producing miniature picture frames in his garage. Two years later he opened his first Hobby Lobby retail space in Oklahoma City. The Hobby Lobby chain grew quickly: to seven stores by 1975, fifteen stores by 1989, 100 hundred stores by 1995, 200 stores by 1999, and over 500 stores by 2015, and nearly 1,000 stores by 2022 in more than forty states.

David Green has been open in attributing the success of Hobby Lobby to God and not to himself. As he has stated, “If you have anything or if I have anything, it’s because it’s been given to us by our Creator” (Grossman 2012). He describes himself as simply a steward: “”This is not our company. This is God’s company. What are we to do? We are to operate it according to the principles He has given us in His word” (Grossman 2012). The religious influence is visible in Hobby Lobby outlets. They play Christian-themed music in the stores, run adds in local newspapers that celebrate Christmas and Easter, shutter their stores on Sundays so that employees can attend worship services, and maintain four chaplains on the corporate payroll. Hobby Lobby has also raised the minimum wage for full-time employees annually, bringing it above the national average, for religious reasons. Green has stated that “it’s only natural: “ God tells us to go forth into the world and teach the Gospel to every creature. He doesn’t say skim from your employees to do that” (Solomon 2012).

David Green is listed as one of the 100 richest Americans with over $4,000,000,000 in wealth (“The World’s Billionaires” 2015).  Active leadership of Hobby Lobby and the Museum of the Bible is now passing to David Green’s son and company president Steven Green. [Image at right] Born in 1964, Steven Green is a Southern Baptist and a grandson and nephew of Pentecostal pastors. He met his wife, Jackie, in a church camp. The Greens have six children including a daughter adopted from China (Grossman 2014).

Active leadership of Hobby Lobby and the Museum of the Bible is now passing to David Green’s son and company president Steven Green. [Image at right] Born in 1964, Steven Green is a Southern Baptist and a grandson and nephew of Pentecostal pastors. He met his wife, Jackie, in a church camp. The Greens have six children including a daughter adopted from China (Grossman 2014).

David Green is reportedly one of the the largest donor to evangelical causes in the U.S. and has made his Christian commitments a highly visible part of the corporate culture. Indeed, Hobby Lobby allocates half of total pretax earnings to evangelical causes. Among his initiatives are distribution of over 1,000,000,000 copies of Gospel literature throughout Africa and Asia, scripture for young children through OneHope Foundation, distribution of Bible “booklets” in poor nations around the world, and a Bible app for cell phones that makes the text available in over one hundred languages (Solomon 2012). A major source of David Green’s prominence within the evangelical community is his contributions to educational institutions. Among his gifts are a $70,000,000 gift to Oral Roberts University in 2007, $10,500,000 to Liberty University, $16,500,000 to Zion Bible College, and $10,000,000 to Evangel University.

MISSION/PHILOSOPHY

The development of a Bible museum has long been a dream of the Oklahoma-based Green family. This vision can be found in its non-profit tax filing documents. In 2011, for example, the projected museum’s mission was stated as: “To bring to life the living Word of God, to tell its compelling story of preservation, and to inspire confidence in the absolute authority and reliability of the Bible” (Caplan-Bricker 2014; Boorstein; 2014). For David Green, “It’s God, it’s history, and we want to show that” (Solomon 2012). He has insisted that the intent is not to proselytize but rather to simply put visitors in touch with God’s book:

We would like to invite all people to come and learn about the book that has impacted all of our world. So our desire is to engage all people. It’s a book that‘s had a huge impact. It’s been controversial. It’s been loved. It’s been hated. We just think people ought to know about it (O’Connell 2015).

As the public relations firm that the Green’s hired to publicize the planned museum put it, the intent is “to showcase both the Old and New Testaments, arguably the world’s most significant pieces of literature, through a non-sectarian, scholarly approach that makes the history, scholarship and impact of the Bible on virtually every facet of society accessible to everyone” (Lindsey 2014). Green has remained confident about the outcome:

So what? Is that the end of life, making more money and building something?” Green asks, answer already in hand. “For me, I want to know that I have affected people for eternity. I believe I am. I believe once someone knows Christ as their personal savior, I’ve affected eternity (Solomon 2012).

LEADERSHIP/ORGANIZATION

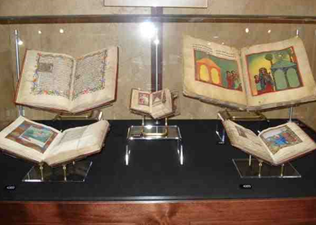

The origination of what would become a Bible museum occurred in 2009 when David Green began searching the world for ancient  sacred manuscripts. He spent over $30,000,000 on his initial acquisitions, although the artifacts are now worth many times that initial expenditure (Rappeport 2014). The first display of the growing collection of artifacts took the form of “Passages,” a touring exhibition. [Image at right] The inaugural display occurred in 2011 at the Oklahoma City Museum of Art; exhibitions followed in Atlanta, Charlotte, Colorado Springs, and Springfield. The exhibitions included features such as holographic recreations of biblical scenes, re-enactments of biblical transcriptions by monks, and a multimedia presentation of the story of Noah’s Ark (Rappeport 2014). Passages was subsequently folded into the larger Museum of the Bible Project. Decisions on acquisitions have been coordinated through the Green Scholars Initiative (GSI), which consists of scholars and consultants from a number of internationally renowned universities and a large number of evangelical liberal arts institutions. GSI has also administered an “elective Bible curriculum for high school students,” The Book: The Bible’s History, Narrative and Impact (Lindsey 2014).

sacred manuscripts. He spent over $30,000,000 on his initial acquisitions, although the artifacts are now worth many times that initial expenditure (Rappeport 2014). The first display of the growing collection of artifacts took the form of “Passages,” a touring exhibition. [Image at right] The inaugural display occurred in 2011 at the Oklahoma City Museum of Art; exhibitions followed in Atlanta, Charlotte, Colorado Springs, and Springfield. The exhibitions included features such as holographic recreations of biblical scenes, re-enactments of biblical transcriptions by monks, and a multimedia presentation of the story of Noah’s Ark (Rappeport 2014). Passages was subsequently folded into the larger Museum of the Bible Project. Decisions on acquisitions have been coordinated through the Green Scholars Initiative (GSI), which consists of scholars and consultants from a number of internationally renowned universities and a large number of evangelical liberal arts institutions. GSI has also administered an “elective Bible curriculum for high school students,” The Book: The Bible’s History, Narrative and Impact (Lindsey 2014).

There was some initial debate over the most appropriate location for the planned museum, but Washington, D.C. ultimately was chosen for its “tourists, robust museum culture and national profile” (Rappeport 2014). In 2012, the Museum of the Bible, the formal name of the Green’s foundation purchased a 400,000 square-foot building that earlier had been a refrigeration warehouse and then the Washington Design Center for $50,000,000 (Rappeport 2014). [Image at right] The building is situated only five blocks five from the U.S. Capitol. Both Passages and the Green Scholars Initiative are components of the Museum of the Bible.

chosen for its “tourists, robust museum culture and national profile” (Rappeport 2014). In 2012, the Museum of the Bible, the formal name of the Green’s foundation purchased a 400,000 square-foot building that earlier had been a refrigeration warehouse and then the Washington Design Center for $50,000,000 (Rappeport 2014). [Image at right] The building is situated only five blocks five from the U.S. Capitol. Both Passages and the Green Scholars Initiative are components of the Museum of the Bible.

At the outset, according to collection managers, the entire collection consisted of “more than 40,000 antiquities [and] includes some of the rarest and most valuable biblical and classical pieces … ever assembled under one roof” (Lindsey 2014). The collection was to be organized into three sections, presenting the history of the Bible, biblical stories, and the Bible’s impact. The roof of the museum featuree a “Biblical Garden” containing biblical-era plant life. The massive collection included items such as large numbers of Dead Sea Scrolls, Torahs, biblical documents written on sheets of papyrus; a copy of Wycliffe’s New Testament; a fragment of the Tyndale New Testament; a portion of the Gutenberg Bible; materials belonging to Martin Luther; and an early version of the King James Bible (O’Connell 2015). Perhaps the hallmark of the collection initially was the Codex Climaci Rescriptus, manuscripts containing New Testament text in Palestinian Aramaic, Jesus’ household language. The text includes the historic utterance by Jesus on the cross, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (“Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani”) (Boorstein 2014). A number of items in the museum collection subsequently became embroiled in controversy (See, Issues/Challenges). Within six months of its opening, the museum had already attracted over 500,000 visitors and surpassed the attendance figures of some of Washington’s prestigious museums for the comparable period (Zaumer 2018)

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Hobby Lobby and the Museum of the Bible has been enmeshed in controversy since the museum’s inception. There have been issues concerning sex-related and health-related policies of the company, a series of instances of legal prosecution over art and antiquity violations, and ongoing controversy over the status of the museum in which it played a founding role.

Hobby Lobby and the Green family have been intimately related and therefore have been jointly involved in a number of controversies. Hobby Lobby became a household name [Image at right] when David Green publicly

opposed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act because it contained a provision mandating companies to provide health care policies that included certain types of birth control. Hobby Lobby has maintained a free health care clinic for staff at its headquarters and has provided employees with insurance that includes several types of contraception coverage. However, the company has opposed intrauterine devices and “morning-after” pills that could “prevent a fertilized egg from implanting in the womb” (Grossman 2014). Hobby Lobby brought suit against the federal government over the contraception mandate that was heard by the Supreme Court. On June 30, 2014, the Supreme Court ruled in Hobby Lobby’s favor in a 5-4 decision that “closely held” stock corporations could exempt themselves from the law (Grossman 2014; Boorstein 2014). The court based its decision not on First Amendment provisions but rather on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

opposed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act because it contained a provision mandating companies to provide health care policies that included certain types of birth control. Hobby Lobby has maintained a free health care clinic for staff at its headquarters and has provided employees with insurance that includes several types of contraception coverage. However, the company has opposed intrauterine devices and “morning-after” pills that could “prevent a fertilized egg from implanting in the womb” (Grossman 2014). Hobby Lobby brought suit against the federal government over the contraception mandate that was heard by the Supreme Court. On June 30, 2014, the Supreme Court ruled in Hobby Lobby’s favor in a 5-4 decision that “closely held” stock corporations could exempt themselves from the law (Grossman 2014; Boorstein 2014). The court based its decision not on First Amendment provisions but rather on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

In 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic was spreading through the population, Hobby Lobby claimed that it was an essential service and declined to close its stores, although the company did later close all of its stores. In 2021, a transgender employee of the company, who had worked at the company for over twenty years and ten years after transitioning, won a civil suit in Illinois over her right to use the women’s restroom

These issues notwithstanding, the primary issues surrounding Hobby Lobby and the Museum of the Bible, which is a private museum, have been the composition and presentation of its collections and its claim to museum status. Theft and forgery of ancient materials is a criminal enterprise of enormous scale; indeed, it is one of the world’s largest illegal markets (Kerse 2013; Lane, Bromley, Hicks and Mahoney 2008). As one observer summarized the matter:

That this stuff is dodgy, it’s not news…. It’s a known thing in the market. If an object doesn’t have a history that proves that it is legal, you just assume that it is illegal, because it probably is.” (Zauzmer and Bailey 2017)

The impact of art and antiquity theft is not simply corruption of the historical record and loss of treasured resources, it is also that the purchase of fraudulent material increases its production. In the case of artifact acquisition, it is important to note that it was Hobby Lobby that purchased the materials in question and so was the target of governmental actions (Zauzmer and Bailey 2017).

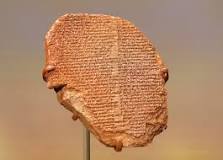

Hobby Lobby had been warned as early as 2009, when the Greens began acquiring artifacts, about questionable acquisition practices. The first major case began in 2017 a few months before the museum officially opened and involved 5,500 artifacts Hobby Lobby had acquired in 2010 for $1,600,000. Hobby Lobby relinquished the Egyptian and Iraqi items in question to the federal government and paid a fine of $3,000,000 (Mashberg 2020). Shortly  thereafter Hobby Lobby agreed to relinquish another 11,,500 artifacts. Among the highest profile items recovered from Hobby Lobby were the Iraqi Gilgamesh Dream Tablet (one of the most ancient religious texts and literary works) [Image at right] and the Afghani Siddur (a rare Afghan Hebrew prayer book is (Zohar 2021). The museum also discovered in 2017 that sixteen Dead Sea Scroll fragments [Image at right] scrolls it had purchased, which were regarded as a centerpiece of the museum’s permanent exhibition, were in fact “deliberate forgeries created in the 20th century” (Mashberg 2020; Greshko 2020; Luscombe 2020). In these various cases, Hobby attributed its violations to a combination of its own inexperience and poor judgment and intentional criminal fraud.

thereafter Hobby Lobby agreed to relinquish another 11,,500 artifacts. Among the highest profile items recovered from Hobby Lobby were the Iraqi Gilgamesh Dream Tablet (one of the most ancient religious texts and literary works) [Image at right] and the Afghani Siddur (a rare Afghan Hebrew prayer book is (Zohar 2021). The museum also discovered in 2017 that sixteen Dead Sea Scroll fragments [Image at right] scrolls it had purchased, which were regarded as a centerpiece of the museum’s permanent exhibition, were in fact “deliberate forgeries created in the 20th century” (Mashberg 2020; Greshko 2020; Luscombe 2020). In these various cases, Hobby attributed its violations to a combination of its own inexperience and poor judgment and intentional criminal fraud.

The most significant challenges to the Museum of the Bible, beyond the scandals surrounding its acquisitions history, are its claims that there actually is “a Bible” and its claim to “museum” status. The latter claim is more salient given its location in Washington, DC in the midst of the capital’s institutions of national public memory and the implications for public understandings of bibles and presentations of history. There has been an outpouring of scholarship on these related issues (Kersel 2021; Moss and Baden 2021; Hicks-Keeton and Cavan Concannon 2022, 2019). Journalists and museum curators and managers have been closely following this history (Kersel 2021; Mashberg 2020; Burton 2020).

Stephen Green has disavowed any intent to use the museum as tool for evangelization, stating that “We’re not discussing a lot of particulars of the book. It’s more of a high-level discussion of here’s this book, what is its history and impact and what is its story” (O’Connell 2015; Sheir 2015). At the same time, he has referred to the Bible as “a reliable historical document” and stated that “This nation is in danger because of its ignorance of what God has taught” (Rappeport 2014). Scholars studying and journalists writing about the museum have offered a much more critical view. Summarizing their scholarly collection, The Museum of the Bible: A Critical Introduction (2019), Moss and Baden state that:

Contributors concluded that the MOTB sanitises church history and whitewashes biblical contents; authorises Christian supersessionism and Christian nationalism; perpetuates colonialist collection practices and archaeological endeavours; centres White Protestantism in the U.S. at the expense of other religious traditions; and has failed to be clear-eyed about its political, institutional, and financial liaisons. The institution capitalises on and reinforces popular conceptions of the Bible as “the good book” as its leaders deny that any particular perspective has shaped its presentation of material….“Taken together,” we wrote in the volume introduction, “the chapters’ collective findings paint a picture of an institution deeply intertwined with the evangelical beliefs and politics of its founding family.”

The challenge presented by the Museum of the Bible, and the dozens of other “bible boosting” private museums and theme parks, is greater than buildings and artifacts. It is that acquisition and presentation practices have been used to create the master narrative that in fact a stable object, “the Bible,” exists and that this conclusion is firmly supported by the assembled artifact record. The more useful analytic perspective is that the museum is creating the very reality that it purports to be simply representing. This imagined history is then legitimated through an institutional designation as a “museum,” which intimates that the site constitutes an institution of national public memory. However, it is more useful and illuminating to understand the museum in the following way: it is “an institution founded, funded, and led by White U.S. evangelicals, the MOTB is principally a robust data set for how White evangelicals in the U.S. make their Bible scriptural (Hicks-Keton 2022:13). From this larger perspective, the Museum of the Bible is significant because represents one strategic side of the ongoing struggle for symbolic supremacy that has continued to envelop American society. To the extent that this Bible is understood to represent a Truth that exists outside of human history and describes the “true nature of things,” it constitutes a powerful symbolic resource for its advocates in their argument for their vision of how to structure society (Frantz 2023).

IMAGES

Image#1: David Green

Image #2: Steven Green

Image #3: A “Passages” exhibition display.

Image #4: The Museum of the Bible building in Washintgon.

Image #5: A Hobby Lobby retail outlet.

Image #6: Dead Sea Scroll fragment.

REFERENCES

Boorstein, Michele. “Hobby Lobby’s Steve Green Has Big Plans for His Bible Museum in Washington.” 2014. Washington Post , September 12. Accessed from http://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/magazine/hobby-lobbys-steve-green-has-big-plans-for-his-bible-museum-in-washington/2014/09/11/52e20444-1410-11e4-8936-26932bcfd6ed_story.html on 10 May 2015.

Burton, Tara. 2020. “A Bible museum is a good idea. The one that’s opening is not.” Vox, April 5. Accessed from https://www.vox.com/identities/2017/11/17/16658504/bible-museum-hobby-lobby-green-controversy-antiquities on 20 November 2022.

Caplan-Bricker, Nora. 2014. “The Hobby Lobby President Is Also Building a Bible Museum for Over $70 Million.” New Republic, March 25. Accessed from http://www.newrepublic.com/article/117145/museum-bible-hobby-lobby-founders-other-religious-project on 10 March 2015 on 10 May 2015.

Frantz, Kenneth. 2023. “The Museum of the Bible and the Politics of Interpretation. Religion and Politics, March 14. Accessed from https://religionandpolitics.org/2023/03/14/the-museum-of-the-bible-and-the-politics-of-interpretation/ on 10 January 2024.

Grossman, Cathy Lynn. 2014. “ Hobby Lobby’s Steve Green stands on faith against Obamacare mandate.” Religion News, March 17. Accessed from http://www.religionnews.com/2014/03/17/hobby-lobby-steve-green-scotus-contraception/ on 10 May 2015.

Hicks-Keeton, Jill. 2022. The Fantasy of ‘the Bible’ in the Museum of the Bible and Academic

Biblical Studies.” Journal for Interdisciplinary Biblical Studies 4:1-18.

Hicks-Keeton, Jill and Cavan Concannon. 2022. Does Scripture Speak for Itself?

The Museum of the Bible and the Politics of Interpretation. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Hicks-Keeton, Jill and Cavan Concannon, eds. 2019. The Museum of the Bible: A Critical

Introduction. Lanham: Lexington/Fortress Academic.

Kersel, Morag. 2021. “Redemption for the Museum of the Bible? Artifacts, provenance, the display of

Dead Sea Scrolls, and bias in the contact zone.” Museum Management and Curatorship 36 (2021): 209-226.

Kersel, Morag. 2013. “Illicit Antiquities Trade.” Pp. 67-69 in The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Volume 3, Edited by Neil Silberman. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lane, David C., David G. Bromley, Robert D. Hicks, and John S. Mahoney. 2008. “Time Crime: The Transnational Organization of Art and Antiquities Theft.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 24:243-62.

Lindsey, Rachel McBride. 2014. “ Passages: A Glimpse into the Hobby Lobby Family’s Bible Museum. Religion & Politics,” September 24. Accessed from

http://religionandpolitics.org/2014/09/24/passages-a-glimpse-into-the-hobby-lobby-familys-bible-museum/ on 10 May 2015.

Bible Museum, Admitting Mistakes, Tries to Convert Its Critics.” New York Times, April 5. Accessed from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/05/arts/bible-museum-artifacts.html on 20 November 2022.

Moss, Candida and Joel Baden. 2019. “Foreword.” P. xi in The Museum of the Bible: A Critical

Introduction, edited by Jill Hicks-Keeton and Cavan Concannon, Lanham: Lexington/Fortress Academic.

Moss, Candida and Joel Baden. 2017. Bible Nation: The United States of Hobby Lobby. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

O’Connell, Jonathan. 2015. “Even Non-believers May Want to Visit the $400 Million Museum of the Bible.” Washington Post, February 12. Accessed from http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/digger/wp/2015/02/12/even-non-believers-may-want-to-visit-the-400-million-museum-of-the-bible/ o n 10 May 2015.

Rappeport, Alan. 2014. “Family That Owns Hobby Lobby Plans Bible Museum in Washington.” New York Times, July 16. Accessed from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/17/us/politics/family-that-owns-hobby-lobby-plans-bible-museum-in-washington.html?_r=0 on 10 May 2015.

Sheir, Rebecca 2015. “D.C. Bible Museum Will Be Immersive Experience, Organizers Say.” NPR, February 25. Accessed from

http://www.npr.org/2015/02/25/388700013/d-c-bible-museum-will-be-immersive-experience-organizers-say on 10 May 2015.

Solomon, Brian. 2012. “David Green: The Biblical Billionaire Backing the Evangelical Movement.” Forbes, October 8. Accessed from http://www.forbes.com/sites/briansolomon/2012/09/18/david-green-the-biblical-billionaire-backing-the-evangelical-movement/ on 10 May 2015.

“The World’s Billionaires: #246 David Green.” 2015. Forbes. Accessed from http://www.forbes.com/profile/david-green/ on 10 March 2015.

Zauzmer, Julie. 2018. “More Than 500,000 People Have Visited the Museum of the Bible in Its First 6 Months.” Washington Post, May 18. Accessed from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/acts-of-faith/wp/2018/05/18/more-than-500000-people-have-visited-the-museum-of-the-bible-in-its-first-6-months/?utm_campaign=27f85d7e01-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2018_05_21&utm_medium=email&utm_source=Pew%20Research%20Center&utm_term=.3c7e7782500a on 24 May 2018.

Post Date:

28 May 2015

Update:

20 November 2022

Some critics remain unsure. Lindsey (2014) has commented that the museum implies that biblical history and national heritage are part of a common story that is still unfolding. Modern-day political battles emerge quite clearly as the “hidden transcript” to the official message of the Bible’s “indestructability”—as another layer of meaning lying just beneath the surface. She explains:

The Museum conveys political arguments through various spokespersons—Martin Luther, Anne Boleyn, St. Jerome—who speak directly to audiences either as video displays or animatronics and who bear witness to the twin virtues of accessibility and individual authority in matters of scriptural interpretation. Passages is decidedly Protestant in conceptualization, positioning Jewish scriptures as incomplete antecedents to Christian scriptures and collapsing the sweep of Jewish history—no matter how recent—into an uncontested “past.” A display early in the exhibit, for instance, moves seamlessly from first-century papyrus fragments to nineteenth-century Torah tiks with no reference to the intervening centuries of cultural, social, or theological development. Catholic history is likewise presented as a historical backdrop, full of textual inaccuracies, deliberate obfuscations, and compulsory interpretations that the Reformation corrected through vernacular translations that “folks like us can understand,” as a peasant woman pleads with her unconvinced neighbor in a video display; and the theological privileging of individual interpretation, as Martin Luther explains in an imaginatively staged video debate with Desiderius Erasmus and Johann Eck in the “Reformation Theater.” The entire sweep of Western history is stitched into a synchronized narrative of the birth of freedom.

For its part, Green has disavowed any resemblance to the Creation Museum or any attempt to use the museum as tool for evangelization. He has stated that “We’re not discussing a lot of particulars of the book. It’s more of a high-level discussion of here’s this book, what is its history and impact and what is its story” (O’Connell 2015; Sheir 2015). One step the museum has taken  to shore up its image is the hiring of scholar David Trobisch [Image at right] to consult on the selection of items to be displayed in the museum and to connect with prestigious universities and scholars (Van Biema 2015) :

to shore up its image is the hiring of scholar David Trobisch [Image at right] to consult on the selection of items to be displayed in the museum and to connect with prestigious universities and scholars (Van Biema 2015) :

Van Biema, David 2015. “David Trobisch Lends Green Family’s Bible Museum a Scholarly Edge.” Religion News, April 27. Accessed from ttp://www.religionnews.com/2015/04/27/david-trobisch-lends-green-familys-bible-museum-scholarly-edge/.

A former Heidelberg University professor, Trobisch also acts as roving ambassador to the worlds of high academia and top-rate museums. His presence poses a conundrum to the Greens’ many critics: As believers that the Bible is God-given and inerrant, could the family — and the museum that is their brainchild — be more open to dispassionate scholarship than previously assumed?

Trobisch describes his relationship with the museum and Steven Green as “two parties standing at opposite ends of the Christian spectrum talking to each other and working together. This almost never happens in the U.S.” He supports the legitimacy of the museum by asserting that on principle he would not be associated with an evangelical mission: “Were the museum to be revealed to be “some kind of missionary activity,” he said, “It would be an enormous disappointment. I could not identify or work for a museum that wanted to do that” (Van Biema 2015).