SALVATION ARMY TIMELINE

1829 (January 17): Catherine Mumford was born in Ashbourne, Darbyshire.

1829 (April 10): William Booth was born in Nottingham.

1855: Catherine Mumford and William Booth married.

1865: William Booth started the Christian Mission in East London.

1878: William Booth launched the Salvation Army.

1880: The Salvation Army officially “invaded” the U.S. as well as India, Ireland and Australia.

1890: Catherine Booth died.

1890: William Booth published In Darkest England and the Way Out .

1891: Red kettles first appeared in San Francisco.

1896: Maud and Ballington Booth (William Booth’s son and daughter-in-law) were forced out of the American command and started Volunteers of America.

1896: Emma Booth Tucker (William Booth’s daughter) and Frederick Booth Tucker took command of the American Army.

1900: Salvation Army provided first disaster relief after the Galveston Hurricane.

1903: Emma Booth Tucker was killed in a train accident.

1904: Evangeline Booth (daughter of William) took over the American Army.

1912: William Booth died and posthumously appointed his son Bramwell as his successor.

1918: Evangeline Booth sends 109 women to “mother” American soldiers fighting in France during World War I.

1929: Bramwell was removed from office by the first Army High Council; the High Council subsequently elected the Army General.

1934: Evangeline Booth became the first woman Army General.

1941: The Salvation Army, National Traveler’s Aid Association, National Catholic Community Service, the Jewish Welfare Board, Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) and Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) together started the United Service Organizations (USO).

1948: Salvation Army became a charter member of the World Council of Churches.

1950: Guys and Dolls, based on Damon Runyon’s sketched of New York City street life and the Salvation Army, debuted on Broadway.

1981: Salvation Army withdrew from the World Council of Churches.

1990: After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Salvation Army recommenced work in several formerly Communist countries.

1995: Married women officers received their own rank.

2001: The Salvation Army sought exemption from anti-discrimination legislation that it contended impinged on its religious freedom. Its request was denied.

2004: Joan Kroc, wife of McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc, donated $1,500,000,00 to the American Army.

2006: Israel Gaither became the first person of color to head the American Army.

2006: Army officials apologized for the physical and sexual abuse of children that occurred in its Australian charity work.

2015: The Army was active in 126 countries and celebrates its 150th anniversary.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

William Booth was born in 1829 to a working-class family in Nottingham, a city in the Wesleyan heartland of northern England. Samuel Booth was a builder who, according to his son William, was always on the make. But his schemes never succeeded and in fact, drove the family (his wife Mary, William and three sisters) into poverty. Poverty did not ennoble the family, and the Booth home was not a happy one. Neither parent had time for religion so the children took themselves to church on Sundays. As the family’s fortunes declined, the Booths moved into smaller homes and shabbier neighborhoods. When William was thirteen, his father lost everything. The teenaged son was pulled from school and apprenticed to a pawnbroker.

Samuel Booth was a builder who, according to his son William, was always on the make. But his schemes never succeeded and in fact, drove the family (his wife Mary, William and three sisters) into poverty. Poverty did not ennoble the family, and the Booth home was not a happy one. Neither parent had time for religion so the children took themselves to church on Sundays. As the family’s fortunes declined, the Booths moved into smaller homes and shabbier neighborhoods. When William was thirteen, his father lost everything. The teenaged son was pulled from school and apprenticed to a pawnbroker.

Working in a pawnshop in a very poor section of town, William made two important discoveries. First, many people had even less than his own family. Second, he wanted a better life for himself.

A hard-working young man, William was befriended by middle-aged couple that invited him to their Wesleyan chapel. Its message stirred his heart, and soon after, he and a friend began street preaching and aiding those in need. William’s efforts to save souls and help the poor helped mitigate the drudgery of his own work, but his pastor rebuffed his efforts. Eager to shake their reputation as overly enthusiastic religious outsiders, Methodists now wanted to be seen as respectable churchgoers. Street preaching did not fit the new image; worse, it challenged the authority of the local minister. But this was the least of Booth’s problems. He had lost his job at the pawnshop and spent a year unemployed. In desperation, he moved to London.

Settled in the big city, Booth again found work at a pawnshop. He also located churches where he could preach on Sundays. Although he felt called to the ministry, he did not see out how he could support himself and provide for his family in Nottingham. Fortunately, a wealthy businessman offered to help him until he found a paid position as a Methodist preacher. This same benefactor also introduced Booth to the Mumfords, a devout Methodist family with a daughter his age. Both later claimed it was love at first sight. Catherine [Image at right] was a deeply thoughtful, tee-totaling Christian. She had very strong convictions about women’s spiritual gifts and the need to use them. Despite her feelings for William, Catherine made it known that she would not marry a man who drank or who was not convicted of women’s equality before God and, therefore, their right to preach. (This was not widely accepted then, especially among conventional churches.)

Although he felt called to the ministry, he did not see out how he could support himself and provide for his family in Nottingham. Fortunately, a wealthy businessman offered to help him until he found a paid position as a Methodist preacher. This same benefactor also introduced Booth to the Mumfords, a devout Methodist family with a daughter his age. Both later claimed it was love at first sight. Catherine [Image at right] was a deeply thoughtful, tee-totaling Christian. She had very strong convictions about women’s spiritual gifts and the need to use them. Despite her feelings for William, Catherine made it known that she would not marry a man who drank or who was not convicted of women’s equality before God and, therefore, their right to preach. (This was not widely accepted then, especially among conventional churches.)

When William Booth proved himself capable of providing for a new family, as well as willing to give up alcohol and to accept female ministry, the two wed. They were well matched. William, too, had strong convictions. The older he grew, the more convinced he became that his gifts were in evangelism rather than local ministry. This belief made it difficult for him to work in a Methodist denomination that expected ministers, especially young ones, to defer to their elders and accept the assignments they were given. Despite a growing family (the Booths had eight children in twelve years), William struck out on his own as an itinerant evangelist. Meanwhile, Catherine had begun public preaching.

The young family, with six children in tow, spent several years moving from place to place as William or Catherine took positions throughout England. In 1865, they returned to London so Catherine could be near her elderly parents. She also could support the family there. Her reputation far exceeded William’s, and invitations to preach, especially among the well-to-do, made her the family’s main breadwinner.

Soon after the Booths settled in, two gentlemen visited William to express their displeasure with Catherine’s preaching and also to offer him a job. They wanted to start a new mission in London’s East End, and they asked him to lead it. The East End, home to London’s poor, was among Europe’s worst slums. Thousands of men, women and children lived in squalid homes; many more slept in warehouses or on the streets. Cholera and smallpox regularly ravaged the population, and children turned to thievery and prostitution.

Booth joined the growing number of the area’s open-air preachers. Sometimes he pitched his tent near a graveyard, other times by a saloon. If he had extra funds, he rented a theater. Booth went where the sinners were, attracted their attention and offered salvation. His ministry grew, and within a few years Booth had several hundred followers and a dozen or so preaching stations. These local outposts responded to community needs with soup kitchens, reading rooms, penny banks and mothers’ meetings. At the same time, Booth had become “fully convinced that the whole world could be brought into submission” (Green 2005:118), and he should lead the charge. But he needed an army to spread the message. In 1878, Booth and several close supporters decided to start a Salvation Army. He was already called “the General,” a nod to the post of general superintendent in the Methodist hierarchy. Moreover, the military metaphor suited his plan for a militant religious force, the spiritual equivalent of Her Majesty’s imperial regiment.

But the notion of a Christian army and its aggressive execution appalled many upright Londoners. Booth’s motley crews, wearing ragtag uniforms and playing off-key instruments, seemed less a Salvation Army than a sacrilegious mob. Their call for abstinence infuriated saloon owners and liquor merchants, and Salvationists spent more time ducking blows than saving souls. When Army women began to preach, the criticism grew. “Hallelujah lassies,” as the women were derisively called, were pelted in the street and decried in the pews.

The attacks strengthened the mission and attracted new recruits. The Army was a magnet for not only for saved sinners but also for idealistic young people. But officers, as the clergy were called, soon realized that the “good news” alone could not feed, clothe or shelter the poor. The Army also needed to meet its followers’ physical needs. Accordingly, Salvationists in England, Australia and the United States (for the Army was now international) began opening food depots and homeless shelters. Cognizant that a more systemic approach was needed, Booth wrote In Darkest England and the Way Out (1890), a book that offered concrete plans to save England’s “submerged tenth.” The response was electric. In Darkest England sold hundreds of thousands of copies on both sides of the Atlantic. Instead of being seen as a religious outsider, “the General,” as Booth was known, became a spiritual statesman.

more systemic approach was needed, Booth wrote In Darkest England and the Way Out (1890), a book that offered concrete plans to save England’s “submerged tenth.” The response was electric. In Darkest England sold hundreds of thousands of copies on both sides of the Atlantic. Instead of being seen as a religious outsider, “the General,” as Booth was known, became a spiritual statesman.

Not everyone was pleased by the development of the Army’s social wing. Some Salvationists felt it was a distraction from their evangelical task. Catherine Booth, often called the “Army mother,” came to accept the new direction although she felt, in the words on historian Norman Murdoch (1996:165), “Soup and soap were, at best, ancillary to soul saving.” Murdoch argues that the Army began the social program because its evangelical crusade had failed. Social salvation was a way to raise money, attract attention, and keep the movement alive. However, Army theologians say the turn to social services was an organic development of the “war on two fronts,” a theological commitment to both individual and social salvation that was in keeping with Jesus’ message.

Some outsiders also panned the social program. During the 1900s and 1910s, critics charged the Army with directing funds raised for social work into evangelical efforts. For its part, the Army denied the charges, offering to open its books to anyone who cared to inspect them. During this period, the Army’s work was supported primarily by private donations. (Salvationists first received money from New York City in 1902 when Frederick Booth-Tucker, a son-in-law of the General, requested funds for work with “fallen women.” Booth-Tucker reasoned that the Army deserved the money since it kept the women from becoming public charges.)

The American Army continued expanding its nationwide network of social services during the first two decades of the twentieth century. Yet, only after World War I did the public perception of the group shift from that of an evangelical movement engaged in relief work to a religiously-based, philanthropic organization. By the early years of the new century, Salvationists were conscious of the need to appear “religious” as opposed to “evangelical” when soliciting funds since donors might not share their specific faith commitments. Thus, Salvationists said their work “non-sectarian” and offered regardless of race, religion, or nationality. Most Americans, however, still saw them as Christian soul-winners, a somewhat rough-and-tumble group that raised money by ringing bells on busy street corners.

The Army’s war work changed all that. The Army deployed both women and men to serve at the frontline. In war-ravaged France, Salvationists set up temporary huts where soldiers could enjoy a taste of home. Female officers baked, sewed, and “mothered” the men. They also they held religious services featuring familiar hymns and popular prayers. But their greatest ministry was day-to-day service; as one correspondent noted, “They let the work of their hands do most of the preaching without ever for an instant forgetting that there’s a big idea somewhere that inspires them” (Winston 1999:218).

Salvationists set up temporary huts where soldiers could enjoy a taste of home. Female officers baked, sewed, and “mothered” the men. They also they held religious services featuring familiar hymns and popular prayers. But their greatest ministry was day-to-day service; as one correspondent noted, “They let the work of their hands do most of the preaching without ever for an instant forgetting that there’s a big idea somewhere that inspires them” (Winston 1999:218).

The Army’s war work exemplified William Booth’s vision of a “practical religion,” which relied on action rather than words. Americans appreciated their efforts and after the war, fundraising was easy. Army leaders did not see their newfound popularity as a threat to their mission since, according to Army historian Edward McKinley, they recognized the need “for centering every welfare program on Christ” (Winston 2013:55). During the post-World War II boom, private funders (grateful for the Army’s help in the Depression and its work with the USO in wartime) gave even more generously. The increase in funds combined with the professionalization of social work had a profound impact on the American organization, now the wealthiest of the worldwide Armies. As programs expanded, so did the numbers of lay staff; between 1951 and 1961 the number of non-Salvationist clerical and social workers doubled. For a movement based on the link between belief and action, this new development troubled some. Likewise, some Salvationists saw the expansion of government funds for social service delivery, a trend that started in the 1960s and ballooned in the 1970s, as problematic.

The Army’s reputation (as a provider of social services, an honest steward, and an efficient charity) made it a favored recipient for government grants. Accepting public funds entailed liabilities: federal agencies wanted to control the programs they financed while Salvationists were accustomed to overseeing their own mix of religion and social service. Moreover, since the First Amendment prohibits federal funding for religious activity, Salvationists were asked to separate the religious from the social aspects of their programs. This meant calculating how much office space, utilities, and manpower went into each, a requirement that undermined the holistic principles of Salvationist theology.

But the desire to serve proved stronger than the concerns about secularizing influences, and today’s Army resolves the tension by providing spiritual counseling as a “value-added” voluntary part of the program paid for with Army funds. With government assistance, the Army started or expanded work in probation supervision, low-cost housing, nutritional services, day-care, and drug rehabilitation. Seeking to maintain their autonomy, Army leaders issued a statement in 1972 that reaffirmed the corps officers’ commitment to evangelism. They affirmed that there was no problem accepting government funds as long as they were not asked to deny their religious identity and mission. This entwined commitment to service and salvation manifests the Army’s understanding of biblically-based evangelical theology even when balancing the two is an ongoing challenge.

Did the American Army, as some of its own members have charged, sell its birthright for a bowl of porridge or, in its case, a $3,.400,000,000 budget? (Salvation Army 2015). Or did it escape the fate of other nineteenth-century legacy institutions (the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Young Men Christian Association, for example) by evolving in ways that honor but update its core values? Some would argue that the Army found a third way: holding fast to its evangelical roots, even when they are hidden in plain sight.

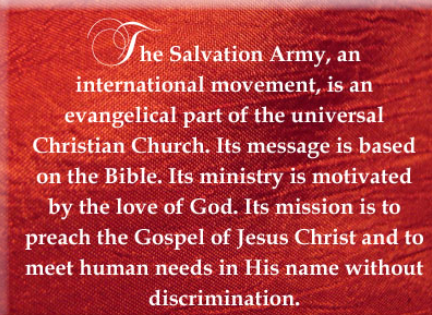

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The Salvation Army is a fundamentalist Christian church, and its tenets echo several of the faiths that influenced founder William Booth. These include Methodism, Wesleyan revivalism, the Society of Friends and the Holiness movement. From Methodism came a belief in structure. From the transatlantic Wesleyan and Holiness movements came the belief in sanctification, a second baptism that set apart believers and provided them with spiritual power to redeem the world. From the Friends came the adoption of a simple lifestyle and the notion of one’s spiritual experiences as part of an “inner light.” Unlike most Christian groups, Salvationists do not have sacraments. According to their understanding of holiness, their lives of service are a sacrament much richer and deeper than symbolic acts such as baptism or communion.

Booth’s experiences with British and American reform and revivalist movements shaped his notions of creeds and doctrines. By 1878, he expressed his position in eleven articles of faith. These articles reflected a conservative evangelical worldview that conceded nothing to new findings in science and biblical scholarship. Booth’s statement affirmed a Trinitarian godhead, the Bible as the inspired word of God, Jesus’ virgin birth and atoning death, a literal Heaven and Hell, and salvation though faith and repentance. This was an “old-fashioned faith,” as Booth averred a year later, “We are a salvation people—this is our specialty—getting saved and keeping saved and then getting someone else saved” (Winston 1999:23).

1878, he expressed his position in eleven articles of faith. These articles reflected a conservative evangelical worldview that conceded nothing to new findings in science and biblical scholarship. Booth’s statement affirmed a Trinitarian godhead, the Bible as the inspired word of God, Jesus’ virgin birth and atoning death, a literal Heaven and Hell, and salvation though faith and repentance. This was an “old-fashioned faith,” as Booth averred a year later, “We are a salvation people—this is our specialty—getting saved and keeping saved and then getting someone else saved” (Winston 1999:23).

Booth believed in the reality of Hell, but he also realized that a gloomy, fearful religion was a hard-sell, especially among down-and-outers. He wanted a “red-hot” faith whose raucous music attracted sinners and whose righteous message convicted them. Booth, who had little use for theology, was committed to “practical religion’ and a “war on two fronts.” According to his biographer, Roger Green, the General realized “redemption meant not only individual, personal, and spiritual salvation, but corporate, social, and physical salvation” as well (Green 1990). Steeped in the holiness movement, Booth believed that sanctification, a second baptism that imbued believers with spiritual power, enabled Christians to help bring about the Second Coming. A post-millennialist, he hoped to see the Kingdom of God in his lifetime. Booth also believed that institutions as well as individuals could be sanctified and that his Army was corporately called to do God’s work. The Army was in the world but not of it, set apart by its uniforms, its service and its regulated community. Its template for godliness was the Field Book of Orders and Regulations (1922) which spelled out all aspects of Army life, enabling Salvationists to maintain a sanctified life in a yet-to-be redeemed world.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Salvationists do not practice baptism or communion. They believe such rituals are the outward expression of an inner faith, which is best expressed through daily living. However they do mark lifecycle events, including the swearing in of new soldiers, which occurs several times yearly, and the commissioning of cadets, an annual ceremony for the new crop of officers.

Salvationists celebrate Christian holidays, and they hold baby dedications, weddings and funerals. They also have weekly worship services that feature music and singing. In its early years, Salvationist brass bands were among their most distinctive practices. Soldiers and officers were pressed to learn instruments for their open-air evangelism as well as their own services. Today, fewer members know how to play the instruments, and so many local services depend on contemporary Christian praise music. Street evangelists, however, often use vernacular music (such as hip hop, gospel or pop) to attract passers-by. Just as the Army’s musical, street-corner evangelism has become a ritual in some cities, its bell-ringers and red kettles are part of the winter holiday ritual nationwide.

Soldiers and officers were pressed to learn instruments for their open-air evangelism as well as their own services. Today, fewer members know how to play the instruments, and so many local services depend on contemporary Christian praise music. Street evangelists, however, often use vernacular music (such as hip hop, gospel or pop) to attract passers-by. Just as the Army’s musical, street-corner evangelism has become a ritual in some cities, its bell-ringers and red kettles are part of the winter holiday ritual nationwide.

Army congregations are often a mix of cradle Salvationists, local community members and recipients of Army services. Although the Army does not compel its clients to attend its services, they welcome anyone who wishes to attend. From its earliest days, many Salvationist soldiers and officers rose through the ranks after they had been “saved” from poverty, prostitution and addiction. Similarly, many contemporary Salvationists have come to the church through its camps, after school programs and community centers as well as its rehabilitation services and shelters.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

William Booth began the Salvation Army in 1878. It superseded The Christian Mission, which he started in 1865. Even as the Army spread through Britain, a “landing party” arrived in New York in 1880 to support the efforts of Eliza Shirley, a teenaged Salvationist who had arrived in Philadelphia the year before. Soon after, the Army “invaded” Europe, Canada, Australia, India and South Africa. When William Booth died in 1912, his Army was truly international and its work respected worldwide. Although there was no plan for succession, Booth’s will named his son Bramwell, his longtime second-in-command, to take his place. The fourth general, Evangeline Booth, also was a child of the Army Founder. Generals must retire at age sixty-eight, and other than William and Bramwell Booth, usually serve less than ten years. (William served thirty-four years and Bramwell led the Army for seventeen years.)

spread through Britain, a “landing party” arrived in New York in 1880 to support the efforts of Eliza Shirley, a teenaged Salvationist who had arrived in Philadelphia the year before. Soon after, the Army “invaded” Europe, Canada, Australia, India and South Africa. When William Booth died in 1912, his Army was truly international and its work respected worldwide. Although there was no plan for succession, Booth’s will named his son Bramwell, his longtime second-in-command, to take his place. The fourth general, Evangeline Booth, also was a child of the Army Founder. Generals must retire at age sixty-eight, and other than William and Bramwell Booth, usually serve less than ten years. (William served thirty-four years and Bramwell led the Army for seventeen years.)

In 2015, The Army was located in 127 countries worldwide. From its London hub, it is divided into geographic territories, which are subdivided into divisions. In this hierarchal structure, both territories and divisions have regional leaders that follow orders from International Headquarters. At the local level, Army churches are called corps, clergy are officers, and laypeople are soldiers. Thanks to the influence of Catherine Booth, women are ordained as Army officers and hold positions of leadership. Of the twenty generals who have headed the Army, three have been female.

The London headquarters, as of 2015, estimates there are more than a million Salvationists worldwide. There also are 13,826 corps and 26,673 officers. The International Army oversees 10,211 community development programs, 440 homeless hostels and 252 residential homes for addicts. Other social service programs include homes for children and for the elderly, community day care, non-residential treatment programs, refugee aid, disaster aid, hospitals and maternity homes. The American army is among the wealthiest in the world, and is better known for its humanitarian service than for its evangelical outreach. (In other countries, the Army is perceived first and foremost as a church.) The American army oversees 582 group homes/temporary housing units, 269 senior citizen centers, 168 service centers and 141 rehabilitation centers among other services that serve over 27,000,000 people annually. Its 2014 revenue was $4,000,000,000, over half of which came from public support and eight percent from government funding. For more than two decades the Army has been among the top five charitable fundraisers in the U.S.

and 26,673 officers. The International Army oversees 10,211 community development programs, 440 homeless hostels and 252 residential homes for addicts. Other social service programs include homes for children and for the elderly, community day care, non-residential treatment programs, refugee aid, disaster aid, hospitals and maternity homes. The American army is among the wealthiest in the world, and is better known for its humanitarian service than for its evangelical outreach. (In other countries, the Army is perceived first and foremost as a church.) The American army oversees 582 group homes/temporary housing units, 269 senior citizen centers, 168 service centers and 141 rehabilitation centers among other services that serve over 27,000,000 people annually. Its 2014 revenue was $4,000,000,000, over half of which came from public support and eight percent from government funding. For more than two decades the Army has been among the top five charitable fundraisers in the U.S.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

In its early years, the Salvation Army faced internal and external challenges. Several leaders tried to wrest the American army from the General’s command, but their efforts were stymied by Booth’s long reach and the deployment of his children to allay any conflict. The most significant breach arose in 1886 when Booth decided to remove his son Ballington and daughter-in-law Maud from the American command. Booth deemed Maud and Ballington too independent, and he did not like what he perceived as the Americanization of his troops. When the couple refused to transfer, he sent his daughter Evangeline to assert his control. After several showdowns, Evangeline did wrest the Army from the Ballington Booths and facilitated the installation of another sister, Emma, and her husband, Frederick Booth-Tucker as national commanders. The Ballington Booths remained in New York and subsequently launched the Volunteers of America, an organization similar in identity and mission to the Army.

the General’s command, but their efforts were stymied by Booth’s long reach and the deployment of his children to allay any conflict. The most significant breach arose in 1886 when Booth decided to remove his son Ballington and daughter-in-law Maud from the American command. Booth deemed Maud and Ballington too independent, and he did not like what he perceived as the Americanization of his troops. When the couple refused to transfer, he sent his daughter Evangeline to assert his control. After several showdowns, Evangeline did wrest the Army from the Ballington Booths and facilitated the installation of another sister, Emma, and her husband, Frederick Booth-Tucker as national commanders. The Ballington Booths remained in New York and subsequently launched the Volunteers of America, an organization similar in identity and mission to the Army.

In 1922, when Evangeline commanded the American army, her brother Bramwell, now the Army General, attempted a similar maneuver to remove her from power. Bramwell wanted direct control of the American army and indicated his intention to transfer his sister and eliminate the post of national commander. When Evangeline lined up significant support to thwart his plan, Bramwell backed down. However the two continued to fight over administrative control of the American army and its emphasis on social service delivery, which Bramwell felt overshadowed its evangelical outreach. Their animosity peaked in 1929 when Evangeline led a group of officers seeking to oust Bramwell, who was physically ailing, from office. These “reformers” also wanted to hold an election for the next General, rather than accept Bramwell’s appointed successor (who would be revealed posthumously in his will). The reformers succeeded on both counts. Bramwell was removed from power and the Army’s High Council elected a new General. To her chagrin, Evangeline did not win the post, which many assumed was her actual reason for leading the reformers.

In addition to leadership challenges, the early Army also faced theological divisions. The Army was rooted in the Holiness movement, and many followers accepted faith-healing. In the early 20 th century Arthur Booth-Clibborn, husband of William’s daughter Kate, asked the General for permission to teach “divine healing,” which many Salvationists already practiced. The General refused even though he affirmed faith healing and its place within the Army. Thus while Booth upheld the ministry, he sought to control its practice, and the effect of his words inhibited faith healing among his followers. However, some Salvationists still continue its practice.

Army’s commitment to the “war on two fronts” also remains an ongoing theological challenge. Many Salvationists, including Catherine Booth, were concerned that social service delivery would outweigh evangelism. In fact, some would argue that the American Army’s financial success justifies that concern since the organization is known widely as a philanthropic agency rather than a church. However, members of the American army, aware of the challenge, constantly seek balance for their two missions, which they believe are conjoined.

In recent years the American army also has encountered challenges to its policy on homosexuality. As a conservative Christian church, the Army supports marriage between one man and one woman, and celibacy for hetero- or homosexuals who are unmarried. However, the Army maintains it does not discriminate against LGBTQ people in service delivery or in hiring, although in 2001 it tried unsuccessfully to receive an exemption from anti-discrimination legislation on religious grounds. LGBTQ activists and supporters have challenged the Army’s stance in Great Britain, Canada and New Zealand as well as in the U.S., and American opponents have urged the public to boycott its annual Christmas drive.

church, the Army supports marriage between one man and one woman, and celibacy for hetero- or homosexuals who are unmarried. However, the Army maintains it does not discriminate against LGBTQ people in service delivery or in hiring, although in 2001 it tried unsuccessfully to receive an exemption from anti-discrimination legislation on religious grounds. LGBTQ activists and supporters have challenged the Army’s stance in Great Britain, Canada and New Zealand as well as in the U.S., and American opponents have urged the public to boycott its annual Christmas drive.

The Army also has faced charges of gender and religious discrimination within its ranks. Many of the Army’s social service programs, especially those financed by government funds, are open to employees of any, or even no, faith. However, non-Christians have complained about discriminatory practices, and in 2004 the New York Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit charging the organization with religious discrimination. When the suit was settled in 2014, the Army was required to give New York employees who work in government funded programs a document that said they would not be asked about their religious beliefs nor would they need to follow the Army’s religious beliefs at work. Concerns about gender equality also have roiled the Army. The Army was among the first Protestant denominations that allowed women to preach and to hold leadership positions. Three of the William Booth’s daughters headed the American army and one commanded the international organization. But by the late twentieth century, some Army women felt they were slotted into women’s work (overseeing family or educational programs). And while single women were promoted on their own merits, married women were dependent on their husbands’ for promotion. (All three women who headed the International Army were unmarried.) In the twenty-first century, Army women hope to see more opportunities for married women. As a start, wives pay will be decoupled from their husbands (instead of family pay, each partner will be compensated separately for their work and individual years of service). Married woman also will be offered enhanced opportunities for career development and leadership training.

REFERENCES

Booth, General William. 1890. In Darkest England, and the Way Out . London: International Headquarters of the Salvation Army.

Eason, Andrew M. 2003. Women in God’s Army: Gender and Equality in the Early Salvation Army. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Green, Roger. 2005. William Booth . Nashville: Abingdon Press.

Hattersley, Roy. 2000. Blood and Fire: The Story of William and Catherine Booth and the Salvation Army. New York: Doubleday.

McKinley, Edward H. 1995, Marching to Glory: The History of the Salvation Army in the United States, 1880-1992 . Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmann’s Publishing.

Murdoch, Norman. 1996. Origins of the Salvation Army. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

The Salvation Army. 2015. Annual Report. Accessed from http://salvationarmyusa.org/usn/annual-reports on 25 December 2015.

The Salvation Army. 1922. Orders and Regulations for Field Officers of the Salvation Army. London: Salvationist Publishing and Supplies.

Walker, Pamela J. 2001. Pulling the Devil’s Kingdom Down: The Salvation Army in Victorian Britain. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Winston, Diane. 2013. “The Impact of News on Religious Identity and Philanthropy,” Pp. 59-70 in Religion in Philanthropic Organizations: Family, Friend or Foe, edited by Thomas J. Davis. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Winston, Diane. 1999. Red-Hot and Righteous: The Urban Religion of The Salvation Army. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Post Date:

10 January 2016