MARY BAKER EDDY TIMELINE

1821 (July 16): Mary Morse Baker was born to Mark and Abigail Baker in Bow, New Hampshire.

1838 (July 26): Mary Baker became a member of her local Congregational Church.

1843 (December 10): Mary married George Washington Glover; they moved to South Carolina.

1844 (June 24): George Washington Glover died of yellow fever; Mary returned to her family home in New Hampshire.

1844 (September 12): Mary gave birth to her son, George Washington Glover II.

1849 (November 21): Abigail Baker died.

1850: Mary went to live with her sister Abigail Baker Tilton.

1851: Mary’s son George was sent to live with family friends in New Hampshire.

1853 (June 21): Mary married Daniel Patterson.

1855 (April): In an effort to move nearer to Mary’s son, the Pattersons moved to North Groton, New Hampshire.

1856: George Washington Glover II moved to Minnesota with his caregivers.

1862 (October 10): Mary began treatment for her decades-long ill health under Phineas Quimby at his practice in Portland, Maine.

1864: The Pattersons moved to Lynn, Massachusetts.

1866 (February 3): Mary suffered a fall, with sustaining life-threatening injuries, which healed following a miraculous recovery prompted by her reading of the Bible. This marked the revelatory moment when Eddy discovered the fruits of what would become Divine, later Christian, Science.

1867: Eddy began teaching about her discoveries.

1870: Alongside partner Richard Kennedy, she began a healing and teaching practice in Lynn.

1873: Mary Baker divorced Daniel Patterson, though the two had separated years before.

1875: The first edition of her book, Science and Health, was published.

1876 (July 4): Mary formed the Christian Scientist Association (CSA).

1877 (January 1): Mary married Asa Gilbert Eddy in Lynn.

1878: Mary Baker Eddy successfully sued former students, including Edward J. Arens, for plagiarism.

1879 (April 12): The Church of Christ, Scientist was formally gathered, replacing the CSA.

1879: The Eddys moved to Boston.

1881 (January 31: The Massachusetts Metaphysical College was chartered.

1882 (June 3): Asa Gilbert Eddy died.

1883 (April 14): Mary Baker Eddy launched The Christian Science Journal.

1883: The sixth edition of Science and Health was published with Key to the Scriptures.

1888: The Abby Corner case was brought to trial, which ended in an acquittal.

1888 (November 5): Mary Baker Eddy adopted Ebenezer J. Foster.

1889: Mary Baker Eddy dissolved the Church of Christ, Scientist and the Metaphysical College following the defection of thirty-six members. At this time, she moved to New Hampshire and began her retreat from public life.

1892 (September 23): Mary Baker Eddy reincorporated the Church of Christ, Scientist under the aegis of the “Mother Church” in Boston.

1890s: A plagiarism lawsuit was brought by Julius and Annetta Dresser against Eddy; Eddy won in court.

1894: Construction started on the Mother Church building.

1894 (December): Mary Baker Eddy named Science and Health the pastor of the church.

1895 (January 5): The Mother Church was formally dedicated and held its first services.

1898: Mary Baker Eddy taught her last class.

1907 (March 1): The Next Friends lawsuit was filed, although it was withdrawn in August of that year.

1907: Mary Baker Eddy returned to the Boston area (Chestnut Hill).

1907: Mary Baker Eddy published her memoir, Retrospection and Introspection.

1910 (December 3): Mary Baker Eddy died at home at the age of eighty-nine.

BIOGRAPHY

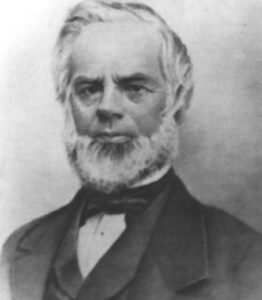

Mary Baker was born on July 6, 1821 to Mark and Abigail Baker in Bow, New Hampshire. She was the youngest of six children, three boys and three girls. [Image at right] Her family had Scottish and English heritage and she grew up profoundly aware of her family’s prominence and status in both New Hampshire and American society, including the fact that she descended from a long line of “strong women” and revolutionary men (Gill 1998:5). Yet, much of what she says about her childhood is specifically religious in scope. She described her mother as “sainted” and the “living illustration of Christian faith,” and her father as somewhat cool, critical, and stringently Calvinist in a manner that she would ultimately come to reject (Eddy 1907:13). Mr. Baker would often subject his family to sustained and loudly narrated prayer sessions, during which he would wax on about the doctrine of predestination, among other things, all while kneeling on the floor. As the lore goes, once, young Mary poked her father in the bottom with a pin during one such session (Gill 1998:9). Though likely the result of a childish boredom, it is perhaps the first example of her growing discomfort with the Christian orthodoxy that surrounded her.

As time passed, and her continuous ill health and tumultuous personal life seemingly came to define her, Mary’s relationships with her father and her siblings, particularly her sisters, were strained. Her favorite brother, Albert, died of an illness in her youth, and her other two elder brothers did not seem particularly keen to foster a close relationship. She had a closer connection with her sisters, but her dependence upon them following her first husband’s death and their irritation at her boisterous son would permanently sour their relationship. Her father left her one dollar upon his death. The only exception to this pattern of familial strain was Mary’s relationship to her mother, with whom she had a warm and loving relationship. Her mother’s death in 1849 would have a profound impact on her already vulnerable state of physical and mental health. The fact that her father remarried after her mother’s death probably exacerbated the strain in their relationship and her well-being.

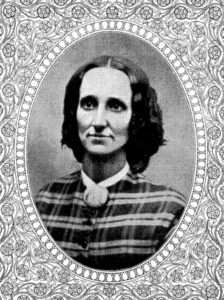

As both photographs and contemporary accounts can attest, [Image at right] Eddy was a striking woman all her life, and was deemed a true beauty by admirers, suitors, and critics alike. Her looks may have enhanced, if not solely explained, her magnetism. In 1843, Mary married Colonel George Washington Glover and moved to Charleston, South Carolina where he was stationed. Within months of their arrival, and in what had become a troubling pattern of illness among Mary’s loved ones, Glover contracted yellow fever and died swiftly, leaving Mary penniless and pregnant. She returned to New Hampshire, shortly thereafter delivering her son, and only biological child, George Washington Glover II. Mary’s sustained postpartum illness separated her from her son (Eddy 1907:31). This separation would become more official when she was compelled, by illness, lack of resources, and the unwillingness of her family to house her rather rambunctious son, to entrust him to guardians. She would make a great effort to regain custody of her son over the ensuing decades, and moved nearer to him when he was brought to Massachusetts by his guardians. Ultimately, his move to Minnesota made any true closeness a moot point, though they corresponded continuously. As Mary neared the end of her long life, the cracks in their relationship would deepen, as money and her disapproval of her son’s choices damaged what little connection they maintained.

Nevertheless, one of the primary reasons Mary married her second husband, Daniel Patterson, in 1853 was to provide a father figure for her son. On that account and in all other ways, the marriage was ill-fated. She moved to North Groton, Massachusetts where her husband’s dental practice was established. Her health continued to worsen; at times she was unable to get out of bed. Though her sustained convalescence was due in part to her perennial ailments, her husband’s debts and infidelity also contributed to her debilitated state of body and mind. By the early 1860s, Mary was depressed, destitute, and at a personal and spiritual crossroads.

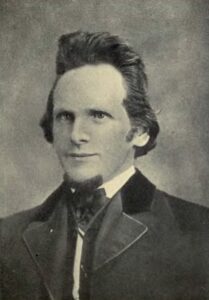

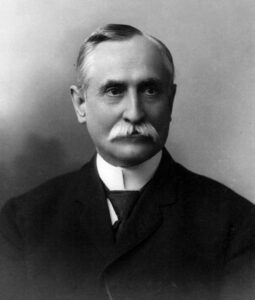

It was in 1862 that events ensued that would precipitate a shift in Mary’s life that, by century’s end, would see her becoming the “most powerful woman in America” (Gill 1998:119). She entered this new period at a physical low point, having sought relief for her many chronic and acute ailments through a variety of methods, including hydropathy and “diet” cures. The mid- to-late nineteenth century was rife with new and alternative health and wellness fads. Many, if not most, of these wellness programs linked the body to the soul or mind and posited that disease was rarely caused by microbes alone, and often had a spiritual, supernatural, emotional, or  intellectual cause (Griffith 2004; Grainger 2019). Mary had little luck with any of these methods, however, until she read about the healing successes of Phineas Parkhurst Quimby (1802–1866). [Image at right] In 1862, she wrote and asked if he would attempt to heal her. Their acquaintance would prove to be one of the most generative for Mary’s future as a healer, as well as the most trying for her career as a religious leader.

intellectual cause (Griffith 2004; Grainger 2019). Mary had little luck with any of these methods, however, until she read about the healing successes of Phineas Parkhurst Quimby (1802–1866). [Image at right] In 1862, she wrote and asked if he would attempt to heal her. Their acquaintance would prove to be one of the most generative for Mary’s future as a healer, as well as the most trying for her career as a religious leader.

Quimby had begun his mesmerist healing practice in 1840 in Portland, Maine. Mesmerism, or animal magnetism, was premised on the idea that an “invisible force” or substance connected all living beings, including human beings. Trained practitioners could manipulate this substance using various techniques, including magnets or hypnosis. After some time, Quimby became convinced that the success of a particular healing was the result of the patient’s state of mind: if the patient desired to be healed and believed it possible, healing would occur. This discovery represented the rudiments of Mind Cure, which posited that all healing began in the mind and not via the external efforts of physicians or chemical treatments (Hughes 2009).

Ultimately, Mary reported feeling better, albeit not cured, almost immediately after her first visits with Quimby. [Image at right] She praised Quimby to whomever would listen, while at the same time beginning to draw upon Christian texts, language, and theology in her explanations for why healing may have occurred. To Quimby’s relational understanding of healing (meaning that the healer and the patient enact healing together) she added God, creating a healing “trinity” (Gill 1998:132). She would continue to correspond with him and seek healing, which, both she and he believed he could do from afar (a practice called “angel treatments”), until his death from cancer in January 1866 (Gill 1998:134).

1866 was a watershed year for Mary in other ways. In 1864, she had moved to Lynn, Massachusetts to be with her husband, though her marriage was failing. On February 3, 1866, Mary slipped on the ice on a street corner and was knocked unconscious. Mary’s injuries were pronounced incurable. At best, her doctor said, she would be paralyzed and at worst, she would die. At some point during this ordeal, Eddy asked for her Bible and began reading accounts of Jesus’ healings.

Precisely what occurred that allowed Mary to rise from her bed, fully healed, she could not articulate at the time. Later, as Gill notes, she transformed her recovery as a moment of divine revelation, which she described as the “falling apple” that led her “to the discovery [of] how to be well myself and how to make others so” (Eddy 1907:38). Her realization was not a physical law such as gravity, but a “divine law” which was also in “accord” with science. She knew that the “divine Spirit had wrought the miracle,” but she determined to make a study of the Bible to explain precisely how, so that she replicate and spread her findings (Eddy 1907:38–39).

The next few years found Mary bouncing from home to home, sometimes staying with friends and other times living in boarding houses, as she began to develop her theological doctrine of healing and a healing practice. In 1870, she established her first practice in partnership with Richard Kennedy (b. ca. 1850?). Ultimately, Kennedy took on the bulk of the healing so that Mary could continue writing and teaching about Christian Science. Unfortunately, the partnership would deteriorate after she critiqued what she believed were “mesmerist” practices in Kennedy’s healings, a movement from which she wanted to distance herself and her theories, which she viewed as the result of human machinations and not divine intervention.

Mary’s most important work during this time, and one that she would never cease to edit, add to, and adapt on a nearly daily basis, was her composition of Science and Health. The book was first published in 1875 and was deemed both a critical and commercial failure. She had not yet found her audience, but its assertions were also radical (the notion that all reality is spiritual and that human beings are immortal, that their physical bodies are projections of their minds) while simultaneously claiming to be Christian. New editions would emerge as she clarified and systematized the doctrine and theology of Christian Science. As Gill notes, Christian Science “relies for its authority on text,” specifically that of the Bible and Science and Health (Gill 1998:318). Though Mary would maintain that the Bible was the only sacred scripture that a Christian needed once they knew the truth of Divine Science, her own book became a smashing success. Science and Health not only catapulted Mary and Christian Science into a national and international spotlight, but set her up financially, so much so that by the time of her death she was a very wealthy woman with many claimants clamoring for access to her estate. However, the book would also be subject to scrutiny from the press and religious critics, as well as accusations of plagiarism from the acolytes of Quimby and among members of the burgeoning New Thought movement.

On the grounds of desertion and adultery, Mary divorced Daniel Patterson in 1873, and married Asa Gilbert Eddy (ca. 1832–1882) in 1877, whom she deemed the love of her life and her greatest supporter. [Image at right] She had treated him in 1875 and he had joined the growing movement of Christian Scientists prior to their marriage. By all accounts, their marriage, albeit short-lived, was a happy one (Eddy 1907:60). In 1882, Gilbert Eddy died of heart disease, though Mary attributed it to “malicious animal magnetism,” or mental poisoning by mesmerist practitioners. “Death” was a troubling proposition for Christian Scientists, as it seemed to highlight the failure of healing. Some used her insistence that Gilbert had died of malicious animal magnetism as fodder for their view of Mary Baker Eddy as insane. She would eventually renounce this view (though not her belief in the reality of malicious animal magnetism, which she would hold for the rest of her life), making peace with her husband’s death as God’s will.

Personal tragedies aside, the 1880s were a time of institutional edification for Eddy and Christian Science. She had started the Christian Scientist Association in 1876, which was replaced in 1879 by the Church of Christ, Scientist. In 1881, she chartered the Massachusetts Metaphysical College in Boston, moving to the city in 1882. During the years the college operated, more than a thousand students would take courses, ultimately becoming healers, joining the Christian Science movement, or applying what they learned in private, home settings. In 1883, Eddy established the Christian Science Journal to increase the visibility of Christian Science and Science and Health. Much of the journal’s pages were filled with healing testimonials, which would draw more students and, increasingly, converts to Eddy.

1889 was a turning point for Eddy. A schism occurred in that year, triggered by a court case involving the death of a woman and her newborn (see below). Thirty-six Christian Scientists who wanted to mix Eddy’s healing practices with western biomedicine left. This led Eddy to dissolve all existing institutions in preparation for an institutional overhaul. But in 1892, she invited twelve Christian Scientists to incorporate a church. They broke ground on the structure of the physical church building in Boston’s Back Bay in 1894. In December 1894, she declared Science and Health the pastor of the church, and in January 1895, the First Church of Christ, Scientist (also called “The Mother Church”) was consecrated.

In what would become emblematic of Mary Baker Eddy’s life in the remaining two decades of her life, she did not attend the consecration of the Church, but had a message read in her stead. In 1898, she taught her last class. She had already left Boston by that point, moving to Concord, New Hampshire, though she would return to the Chestnut Hill area of Boston in 1907. There were several reasons for her increasing reclusiveness. She was consistently concerned with the prospect of malicious animal magnetism and its potentially deleterious effects on her. In fact, she would consistently report its effects on her at times that coincided with moments of chaos, public censure, or emotional turmoil. A number of lawsuits clustered during these latter years that would make her wary of all but her closest confidantes. As noted below, her avoidance of church gatherings and her naming Science and Health as pastor of the Church, may well have been done to avoid her idolization. Though Eddy certainly wished to establish herself as the revealer of Christian Science, and therefore would have a crucial role in Christian history, she wished for Christian Science to outlive her and so took steps to ensure that (Voorhees 2011).

Eddy might have felt isolated as a wealthy, powerful woman and a leader of a religious movement who was under constant scrutiny by benefactors and, especially, detractors, and alienated from her own family, including her son. This may explain her decision to adopt a forty-year-old son in 1888. Ebenezer Foster (1847–1930) filled a filial and emotional void for Eddy, even when it seemed plain to those on the outside that he was a social climber. For at least seven years, he was a trusted companion and confidante. Ultimately, he would betray her by joining one of the lawsuits against her, this one laying claim to her estate, a gamble that left him disinherited.

Despite her isolation, or perhaps because of it, Eddy continued to busy herself about the work of Christian Science from her office at Pleasant View, the name of her stately home, in Concord, New Hampshire. She ran a disciplined household (Gill 1998:391; Stokes 2008:456). Her vigor, even into her eighties, was notable and she expected it to be matched by her live-in staff (Gill 1998:397–98). Eddy could be vituperative, quick to anger, and doctrinaire, particularly when it came to the running of her household. She was particularly prone to rages when her staff did not meet her own striving for perfection, which Gill argues was the result of her spiritual pursuit of saintliness (Gill 1998). It is likely, however, that no one was subject to Eddy’s scrutiny and censure more so than herself. She continued to work late into the first decade of the twentieth century, albeit for shortened hours.

Yet, old age comes for all, and the question of succession became more urgent for Eddy. Many of the most obvious candidates, such as the charismatic Augusta E. Stetson (1842–1928), who headed the second largest Christian Science church in New York, seemed to be courting the personal adoration that Eddy had eschewed. One could argue that Stetson, herself a strong, powerful woman, was the victim of her own ambitions. Her ascent to leadership was cut short in 1909 when she was called before a board of Christian Scientists to answer accusations as to whether she had been influenced by mesmerism. With no definitive successor, Eddy’s immediate associates pressed her to delineate how to proceed once she was gone.

Perhaps it was hard for Eddy, whose overcoming of illnesses had come to define her, to imagine her impending death. In general, death was a sticky concept for Christian Scientists, whose theology was premised on the immortality of the spirit and the non-reality of matter, the body included. Would the body actually die if it was a projection of the mind, and the mind was immortal spirit? Or would it simply fall into a prolonged sleep until some appointed time? For Eddy, as the face of Christian Science, the question bore particular significance. Then in November 1910, Eddy caught a cold. She died on December 3.

Although newspapers had been erroneously reporting her death for years, her actual obituary would make national news. She was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. [Image at right] Her grave is frequently visited by Christian Scientists and those outside the faith. Nonmembers may well have heard the legend of the telephone. Supposedly, a telephone has been placed by her tombstone, mysteriously ready for use when Eddy should awake from her long sleep and require transportation. Most Christian Scientists would dispute this legend. They believe that resurrection begins during one’s life once one has accepted Christian Science’s main principles. They do not expect to see Eddy’s bodily return to earth. Christian Scientists who visit her grave do so to be close to her, which may transgress the line between leader and idol that Mary Baker Eddy herself was so careful to avoid crossing.

TEACHINGS/DOCTRINES

Since the religion of Christian Science is virtually synonymous with Mary Baker Eddy, the WRSP entry “Christian Science” offers a fuller delineation of Eddy’s teachings and doctrines. A brief overview is provided here.

For the most part, Eddy’s teachings are recorded in her magnum opus, Science and Health. Despite variations between the first (1895) and last (1907) editions. In 1883 in the sixth edition of Science and Health, Key to the Scriptures was first added to the volume, which was enlarged and revised in subsequent editions of the book (Mary Baker Eddy Library 2015:4–8). There are certain central positions that carried over in the various editions of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, and represent the crux of Mary Baker Eddy’s belief and that of Christian Science.

Eddy listed six tenets, several of which aligned with the dominant Protestant Christianity of her day and some that highlighted her radical reinterpretation of certain doctrines. Among the former were tenets that established the Bible as the only tool necessary for eternal life, that God the Father was supreme and infinite, that Jesus Christ was his son, and that human beings were created in God’s image (Eddy 1901:497, 3–27). It is of note, however, that several Christian doctrines were adapted or challenged by Eddy. For example, she believed human beings were themselves immortal; not “of” God, but like God and necessary to God in many respects. She also proposed a dual-gendered deity: a Father-Mother God, one that was both masculine and feminine and therefore perfectly balanced and reflective of humanity (Voorhees 2021:127). Most clearly transgressive of Protestant orthodoxy, were those tenets that established sin as the wrongful belief that evil exists and, perhaps most importantly, that “reality is spiritual, eternal, and unchanging” (Gill 1998:209). Matter, then, was actually spirit or “mind,” which was God.

Theology and healing practice were always linked for Mary Baker Eddy. Disease and illness, while manifesting as forms of bodily suffering, pain, and weakness, were the result of sin. Sin, as noted, was wrong belief in the reality of evil, which in the realm of health, meant that disease itself, as a physical manifestation of evil, was unreal. Disease, in other words, had an intellectual and spiritual, rather than physical, root. Thus, once one realized the root of disease, the Christian Science practitioner could heal physical ailments, infirmities, and diseases, just as Christ could. Not through miracles, which implied events that occurred outside of the natural order, but through prayer and right belief.

The “science” component of Christian Science was equally key to Eddy’s religious thought. [Image at right] Her belief that the system of Divine Science was scientific was shared by a variety of other religious leaders and groups, some of whom were Christian. These groups, and Eddy, sought to apply the method of science to an established or emerging system of beliefs. At the same time, the claim of science spoke directly to the healing practices of Christian Science, which produced quantifiable results. That Christian Science promised real-world results, rather than other-worldly promises, was certainly attractive for those seeking healing, as well as a target for critics. However, Eddy did not separate the this-wordly from the other-worldly components of Christian Science healing: proper belief meant proper health.

Just as Eddy was adamant about what Christian Science was, she was equally adamant about what it was not. It was neither Spiritualism nor Theosophy, though she was often accused of dabbling in both. Both of these movements were led by women, and both seemed to dissolve the line between the spiritual and physical, claim special knowledge delivered by a higher or spiritual being, and challenge traditional Protestantism. In contrast, Eddy’s theology was deliberately Christian and biblical, even as it resisted the traditional interpretation of both. Eddy wished to distance herself from mesmerism and New Thought. Although she believed in the power of mesmerist practice, particularly malicious animal magnetism, she believed it derived from human intention not a supernatural source and certainly not from God (Eddy, Science and Health 1901: 1–8, 102). New Thought, on the other hand, served as both a competitor and antagonist. Like Christian Science practitioners, New Thought adherents claimed a similar ability to heal through proper belief or thinking. Even more troubling was the fact that many in the New Thought movement were behind accusations that Eddy had plagiarized her religious system. Thus, while Eddy did many things to mute her personal uniqueness, she did everything she could to highlight the special and distinctive system of Christian Science, often over against these other nineteenth-century religious systems.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Mary Baker Eddy is less known for her ritual legacy than she is for her theological and institutional contributions. The practical component of her religious work, healing, emerged in conjunction with the systematization of her theology and the founding of a formal religious institution. In this sense, then, it is possible to focus on several areas of Eddy’s religious practice that were important, even central, to her life and work, namely: prayer, abstention, the healer-seeker relationship, and study. These form the backbone of current Christian Science practice.

Prayer is at the center of Christian Science healing practice. One of the primary ways that Eddy differentiated herself from mesmerist and certain forms of New Thought practice was by making prayer, specifically to a traditionally Christian God, the main channel through which healing takes place. Prayer is believed to be efficacious when the practitioner believes in the central truth of Christian Science: that everything is spirit (or mind) and spirit is God.

Similar to many religious leaders during the nineteenth century, Mary Baker Eddy was attentive to how bodily practices, particularly diet, impacted one’s spiritual health. Eddy abstained, and recommended abstention, from alcohol and other mind-altering substances. She also maintained a simple diet, although apparently had a sweet tooth and ate dessert nearly every night while at Pleasant View (Gill 1998:392). The purpose of abstinence and simplicity is to clear any encumbrances between the mind and soul and God. In this way, as Jonathon Eder argues, Eddy was not a body denier, even though she denied the reality of all matter (Eder 2020). The body, in its earthly context, houses the soul and therefore can be either a hospitable or inhospitable home for it. Eddy often mentioned strength as a virtue, and not simply that of a strong mind or soul. Most famous, however, was Eddy’s abstention from traditional biomedical practices. Though all of the practices relating to her health and that of her Christian Science followers stem from a belief that disease and its cure are linked to the mind and spirit, it was Eddy’s avoidance of medical practices that follows most directly from this belief.

As a healer and as one who experienced healing, Eddy felt that mutual belief in God and the ability of God to heal was crucial to successful healing. This is one of the primary ways that Eddy’s healing practice and the religion of Christian Science first overlapped and continue to overlap. From Phineas Quimby, she had certainly come to an understanding that the mindset of the person requiring healing was crucial to healing success. This was true for Eddy, but it had a more explicitly religious grounding. “Wrongful thought,” for Eddy is the root of sin, which itself is the root of disease. In other words, healing cannot occur without proper belief in the principles of Christian Science by both healer and the person being healed. Existing in a state of belief is also crucial for one of the primary ways that healing can occur: across distances. Eddy believed that a healer did not have to be present to heal a person, but could heal from afar (a belief that she saw modeled by Quimby), provided that the person sincerely sought healing and was a believer in the basic principle of Christian Science: that all matter was mind or spirit and that mind or spirit was God.

Finally, Eddy both exemplified and institutionalized the Christian Science practice of study or reading. As a text-based religion, it is not surprising that much of the practice related to the religion occurs between reader and text, hence the creation of Christian Science Reading Rooms. Eddy spent most of her life in her own study of the Bible along with editing and supplementing Science and Health. The notion that her work was done following her Great Discovery was unthinkable to her. Though not a religious ritual in a liturgical sense, study is perhaps one of the most consistent aspects of Eddy’s religious practice, as can be seen in Christian Science Reading Rooms today.

LEADERSHIP

Mary Baker Eddy’s identity and role as a leader passed through a series of intersecting stages: that of a healer, that of a revealer-teacher, that of a religious leader, and that of a religious celebrity and spokesperson.

Her first two roles, as healer and revealer-teacher, emerged almost simultaneously. Following her initial, but short-lived, healing at the hands of Quimby, she evangelized on his behalf. She did not embark upon a healing practice of her own until she had her own theory (or theology) of healing. She began work on the manuscript that would become Science and Health almost immediately after  recovering from her near-fatal fall in 1866. Then in 1870, she formed a partnership with Richard Kennedy with whom she set up a healing practice, and with whom she would ultimately fall out. [Image at right] Kennedy took on the primary role of healer in order for Eddy to have time to teach her healing methods and the truth of Divine Science to those wanting to become healers in their own right. It was the publication of Science and Health that would launch her into a far more public form of leadership. With its publication, Eddy presented herself not only as the purveyor of a new method of healing, but as a revealer of a new sacred text, even as she insisted that the Bible was the source of Divine Science and all of the theological doctrine explained in her book.

recovering from her near-fatal fall in 1866. Then in 1870, she formed a partnership with Richard Kennedy with whom she set up a healing practice, and with whom she would ultimately fall out. [Image at right] Kennedy took on the primary role of healer in order for Eddy to have time to teach her healing methods and the truth of Divine Science to those wanting to become healers in their own right. It was the publication of Science and Health that would launch her into a far more public form of leadership. With its publication, Eddy presented herself not only as the purveyor of a new method of healing, but as a revealer of a new sacred text, even as she insisted that the Bible was the source of Divine Science and all of the theological doctrine explained in her book.

Eddy found particular success as a healer and as a disseminator of healing practices in the field of obstetrics (Stokes 2008: 453). Christian Science arose at a time when medicine was becoming professionalized and discipline-focused, which meant advancement in some ways and regression in others. Women, very often pregnant women, found their bodies increasingly objectified, and their voices silenced. Birth was moving from the sphere of midwifery and toward that of obstetric surgery and the hospital. Eddy’s methods were used and Christian Science practitioners, even, on occasion, Eddy herself, were present at many births; the vast majority had successful outcomes.

As the leader of a religious movement, Eddy had a fine line to walk. She argued vehemently that Christian Science was Christianity, and she was simply the messenger of this last and greatest stage of its evolution. Nonetheless, as Amy Voorhees argues, Eddy was also clear that she was not simply interchangeable with other interpreters of Christian Science, particularly those who claimed to be able to apply Christian Science in a way that moved away from Eddy’s teachings (Voorhees 2011). Eddy was adamant that her way, which she revealed in Science and Health, her courses, and other instructional materials, was the way.

While the method was authoritative, Eddy was careful not to consolidate personal authority in herself alone. A shrewd organizational and financial planner, Eddy knew that the church would need to survive beyond her. She therefore created a hierarchical but democratic structure, with a series of boards governing various aspects of the church. With all of this said, there were few who questioned her authority when pressed. When she dissolved the first Church of Christ, Scientist in 1889 following the schism of 36 church members, she effectively removed herself from the day-to-day running of the organization. Gill writes that Eddy was “the greatest asset to the movement as a divinely guided decision maker” (Gill 1998:350; for contemporary leadership and organization, see “Christian Science”).

To Mary Baker Eddy, the most surprising, occasionally rewarding, but on the whole debilitating, aspect of her role as leader of Christian Science was the fame that it brought her. The press constantly wrote about her, mostly in negative terms, but all of which spoke volumes about the novelty of a powerful, successful woman who claimed a special dispensation from God. Eddy was profoundly aware of the spotlight, knowing that her every move would be picked apart and scrutinized for the slightest whiff of scandal. She was also a firm believer in malicious animal magnetism, but also the mesmerist belief that proximity to too many people, particularly people focusing their energy on her, would drain her of her own (Gill 1998:352). Eddy was certainly contented by the financial comfort that came with her success and visibility. By nineteenth-century standards she was wildly wealthy. Her retreat from the spotlight, only to emerge at select occasions over the next two decades, highlights the fact that she did not court attention, let alone celebrity (or, more to her chagrin, notoriety), even if it courted her.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Over the course of her life, Eddy experienced a series of personal and professional challenges, occasionally experiencing them at the same time. Her first two husbands left her bereft, albeit for very different reasons, and her relationship to the Bakers, her family, was fraught. Her relationship to her biological son was strained, becoming more so as the years went on, and the bond with her adopted son frayed.

It was her short-lived relationship to Phineas Quimby that would prove the first, and arguably the longest lasting, trial for her and specifically to her legitimacy as the founder of Christian Science. No sooner had she published Science and Health than accusations of plagiarism began to fly. Quimbyites and those forming the nascent movement known as New Thought, such as Annetta Dresser (1843–1935) and Julius Dresser (1838–1893), claimed that her ideas were unoriginal and clearly stolen from her former healer and ostensible mentor (Dresser 1895). The accusation of plagiarism was an attractive one for other putative heirs of Quimby’s system of healing, particularly following his death in 1866 when there were those who wished to claim his system for their own healing practices. The press was only too willing to publish these claims without evidence or a statement by Eddy herself. Even Mark Twain wrote a book seeking to expose Eddy as a fraud (Twain 1907), although he also demonstrated a begrudging respect for her ambition and willingness to bring controversial beliefs to light unapologetically.

As Gillian Gill has shown, there is a reason that little actual evidence of plagiarism was publicized and that is because it was weak at best, but more likely non-existent (Gill 1998). Quimby was notoriously scattered and unsystematic in the recording of his thought. What was written down was not easily discerned, nor was any of it recognizable in Science and Health. His works were also withheld from public scrutiny and during a highly publicized plagiarism trial, which Eddy would win, though it would prove incredibly draining. This secrecy made it impossible to compare Quimby’s work with Eddy’s and cast doubt on her accusers since they refused to produce the evidence when pressed. Nonetheless, the accusations clearly troubled her enough that she devoted a chapter of her memoir to “Plagiarism.” Eddy wrote the following:

Christian Science is not copyrighted; nor would protection by copyright be requisite, if mortals obeyed God’s law of manright. A student can write voluminous works on Science without trespassing, if he writes honestly, and he cannot dishonestly compose Christian Science. The Bible is not stolen, though it is cited, and quoted deferentially (Eddy 1907:102).

As Eddy observes here: since Christian Science is truth, to call it plagiarized would be equivalent to calling all citations from or reference to the Bible plagiarism.

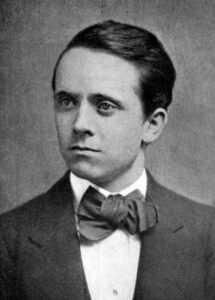

Perhaps most stinging was the fact that several of her former students would lend their voice to the plagiarism suits. Many former protégés, confidantes, and even family members became vocal adversaries when they broke from her, whether they were simply seeking independence, wanting to avoid her critical gaze or censure for their behavior, or were claiming some morsel of her legacy and wealth. Most famous among the lawsuits brought against Eddy, or in this case supposedly “on her behalf,”  was the Next Friends suit filed in March 1907. The premise of the suit was that Eddy was being controlled by those closest to her, chief among them being Calvin Frye (1845–1917), [Image at right] who had been her personal assistant and most loyal and constant companion for decades. Eddy had frequently been the target of “insanity” or “hysteria” accusations, and this was simply the latest iteration of that tactic. The lawsuit claimed that she was too addled to attend to her own affairs and her belief in malicious animal magnetism was provided as justification for the suit. The suit foundered, however, when the character of the defendants (including both of Eddy’s biological and adoptive sons), the scope of the evidence, and Eddy’s own testimony given to an impartial party, led the presiding judge to dismiss it just months after its filing.

was the Next Friends suit filed in March 1907. The premise of the suit was that Eddy was being controlled by those closest to her, chief among them being Calvin Frye (1845–1917), [Image at right] who had been her personal assistant and most loyal and constant companion for decades. Eddy had frequently been the target of “insanity” or “hysteria” accusations, and this was simply the latest iteration of that tactic. The lawsuit claimed that she was too addled to attend to her own affairs and her belief in malicious animal magnetism was provided as justification for the suit. The suit foundered, however, when the character of the defendants (including both of Eddy’s biological and adoptive sons), the scope of the evidence, and Eddy’s own testimony given to an impartial party, led the presiding judge to dismiss it just months after its filing.

Eddy faced threats of mutiny throughout her career; on occasion the threats became reality. Following the Abby Corner case of 1888, the movement seemed most in danger of fracturing irreparably. Abby Corner was a Christian Scientist whose daughter and grandchild died in Corner’s care when she presided over her daughter’s labor. She was brought to trial, but acquitted when it was determined that her daughter’s death could not have been prevented even had a physician been present. Nevertheless, the press pounced on the case and public opinion once again turned on Eddy, who had taught Corner. Dissent within the church seemed to crest at this point, and Christian Science came closest to a schism when a sizeable faction in the Chicago church attempted a coup d’etat (Gill 1998:345). Though Eddy was able to avoid ecclesiastical catastrophe, primarily by distancing herself from Corner, her actions renewed accusations about her supposed vindictive and nasty personality (Gill 1998:346–48; Stokes 2008:447).

Undergirding many, if not all, of these accusations was pervasive cultural misogyny and patriarchy. That Eddy, a woman, particularly one who had had little education and was of meager means, could construct a religious healing system without leaning on the intellect, financial backing, and approval of men or her supposed social betters was unthinkable for many of her critics. Thus, there is a marked irony inherent in her success, in that her gender both contributed to her rise and heightened the antagonism that she and her fledgling movement faced.

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGION

In the scope of female religious leaders, Mary Baker Eddy [Image at right] stands peerless in certain respects: as the creator/revealer of her own sacred text, as the founder and leader of a successful, and sustainable new religious movement, and as a woman who found financial and social independence when both foe and friend sought to divest her of her position. At the same time, she is representative of broader currents in women’s rights that would spark in the nineteenth century and then break forth in earnest during the twentieth century. Though perhaps the best-known female religious leader in her own century, from our vantage point in history we know that she was one among several nineteenth-century religious leaders including Ellen Gould White (1827–1915) of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Though not a social reformer in occupation, her work echoed that of women seeking greater opportunities for women in the public sphere, particularly given the fact that many women who pursued women’s causes often came to that work through their religious institutions or because, and occasionally in spite of, their theological convictions.

Mary Baker Eddy remains a bit of a conundrum, however, when it comes to her relationship to and engagement with the women’s rights movements of her day. Critics have famously commented on the predominantly male hierarchy of the early Christian Science movement, more notable for the fact that women comprised the majority of the members. Gill has noted that this (internalized) misogyny is overblown and that Eddy was far more sympathetic to women’s causes than frequently acknowledged (Gill 1998:415-17). Amy Voorhees argues that the reality was more complex (Voorhees 2012:7-8). Eddy seemed far more willing to acknowledge women’s rights in the language of Science and Health, specifically in reference to a dual male-female deity, at an earlier point in her tenure as Christian Science founder, but she later pivoted to a more classically male designation for God. Thus, Mary Baker Eddy’s position as a woman whose life’s work empowered and helped women and whose personal success inspired them, but who also remained rather fluid in her view of women’s equality, makes her a continued source of consternation and study.

IMAGES

Image #1: Mary Baker Eddy, 1875.

Image #2: Mary Baker circa 1853.

Image #3: Phineas Parkhurst Quimby (1802–1866).

Image #4: Mary Baker Eddy, 1864.

Image #5: Asa Gilbert Eddy (1832–1882), third husband of Mary Baker Eddy.

Image #6: Monument to Mary Baker Eddy, Mount Auburn Cemetery, four miles west of Boston, Massachusetts.

Image #7: Mary Baker Eddy, 1891.

Image #8: Richard Kennedy, partner in healing with Mary Baker Eddy’s first practice.

Image #9: Calvin Frye, personal assistant and loyal confidante of Mary Baker Eddy.

Image #10: Mary Baker Eddy. Library of Congress and Wikimedia Commons.

REFERENCES

Dresser, Annetta Gertrude. 1895. The Philosophy of P. P. Quimby. Boston: George H. Ellis.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1907. Retrospection and Introspection. Boston: Joseph Armstrong, Publisher.

Eddy, Mary Baker. Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures. Multiple editions.

Eder, Jonathon. 2020. “Manhood and Mary Baker Eddy: Muscular Christianity and Christian Science.” Church History 89:875–96.

Gill, Gillian. 1998. Mary Baker Eddy. Reading, MA: Perseus Books.

Grainger, Brett. 2019. The Church in the Wild: Evangelicals in Antebellum America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Griffith, R. Marie. 2004. Born Again Bodies: Flesh and Spirit in American Christianity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hughes, Ronald. 2009. Phineas Parkhurst Quimby: His Complete Writings and Beyond. Howard City, MI: Phineas Parkhurst Quimby Resource Center.

Mary Baker Eddy Library. 2015. “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures Milestones,” 1–9. Accessed from https://www.marybakereddylibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/SHMilestones.pdf on 10 October 2021.

Piepmeier, Alison. 2001. “‘Woman Goes Forth to Battle with Goliath’: Mary Baker Eddy, Medical Science, and Sentimental Invalidism.” Women’s Studies 30:301–28.

Stokes, Claudia. 2008. “The Mother Church: Mary Baker Eddy and the Practice of Sentimentalism.” The New England Quarterly 81:438–61.

Twain, Mark. 1907. Christian Science. New York: Harper and Brothers.

Voorhees, Amy B. 2021. A New Christian Identity: Christian Science Origins and Experience in American Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Voorhees, Amy B. 2012. “Mary Baker Eddy, the Woman Question, and Christian Salvation: Finding a Consistent Connection by Broadening the Boundaries of Feminist Scholarship.” Journal of Feminist Studies of Religion 28:5–25.

Voorhees, Amy B. 2011. “Understanding the Religious Gulf between Mary Baker Eddy, Ursula N. Gestefeld, and their Churches.” Church History 80:798–831.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Albanese, Catherine. 2007. A Republic of Mind and Spirit: A Cultural History of American Metaphysical Religion. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Baxter, Nancy Niblack. 2008. Mr. Dickey: Secretary to Mary Baker Eddy with a Chestnut Hill Album. Carmel, IN: Hawthorne Publishing.

“Christian Science Official Website.” Accessed from https://www.christianscience.com on 5 October 2021.

Christian Science Publishing Company. 2011, 2013. We Knew Mary Baker Eddy, Expanded Version, 2 Volumes.

Gottschalk, Stephen. 2006. Rolling Away the Stone: Mary Baker Eddy’s Challenge to Materialism. Bloomington: Indiana University.

McNeil, Keith. 2020. A Story Untold: A History of the Quimby-Eddy Debate. Carmel, IN: Hawthorne Publishing.

Simon, Katie. 2009. “Mary Baker Eddy’s Pragmatic Transcendental Feminism.” Women’s Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 38:377–98.

Wallner, Peter A. 2014. Faith on Trial: Mary Baker Eddy, Christian Science and the First Amendment. Concord, NH: Plaidswede Publishing.

Willsky, Lydia. 2014. “The (Un)Plain Bible: New Religious Movements and Alternative Scriptures in Nineteenth Century America.” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 17: 13–36.

Publication Date:

13 October 2021