APOSTLES OF INFINITE LOVE TIMELINE

1905 (September 15): Michel Collin was born in Béchy, Lorraine, France.

1928 (September 8): Gaston Tremblay was born in Rimouski, Quebec, Canada

1933 (July 9): Collin was ordained to the priesthood in Lille, France.

1935 (April 28): Collin had a vision that resulted in the foundation of the Apôtres de L’Amour Infini (the Apostles of Infinite Love).

1940: Tremblay had a vision of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, saying that he would found a “Company of Mary.”

1944 (August 15): Tremblay entered the community of Hospitalers of St. John of God in Montreal.

1949 (August): Tremblay had a vision of a future pope.

1950 (October 7): Collin had a vision that God crowned him pope.

1951 (January 17): In a decree, the Holy Office reduced Collin to lay status.

1952: Tremblay left the Hospitalers

1952: Together with two others, Tremblay founded the Brothers of Jesus Mary. He took a new name, Jean de la Trinité (Fr. John of the Trinity).

1953 (May 13): Archbishop Paul Émile Léger of Montreal authorized the Brothers of Jesus Mary.

1958 (September): The community moved to a farm in St-Jovite the Laurentian Mountains.

1961 (March): Fr. John and Collin met in Montreal.

1961 (March 25): Collin, as Clement XV, made his papal claims public.

1961 (April 4): Clement XV founded L’Église Renovée (the Renewed Church).

1962 (January 21): Clement XV ordained Fr. John to the priesthood.

1962 (March 25): Collin consecrated Fr. John bishop and made him the superior of the Order and responsible bishop for Canada.

1962: The Canadian community changed the name to the Apostles of Infinite Love.

1962 (May 10): Bishop Eugène Limoges of Mont-Laurier placed an interdict on the Apostles of Infinite Love.

1963: The Apostles started to build a big monastery at St-Jovite.

1963 (June 9): After the death of John XXIII, Clement XV was coronated.

1963–1966: The community at St-Jovite multiplied. The group included both brothers and sisters, lay disciples and children.

1966 (December 28): The first police raid against St-Jovite took place.

1967 (January 21): Clement XV suspended Fr. John as the superior of the Order and the bishop of Canada.

1967-1968: New police raids, investigations and legal battles took place.

1968 (June 24): Fr. John claimed that God elected him Gregory XVII, the Universal Shepherd of the Church, supplementing Clement XV. Still, he was most often called Fr. John Gregory.

1969 (May 9): In a letter, Clement XV accepted Fr. John as his successor.

1971 (September 29): The bishops of St-Jovite crowned Fr. John Gregory as Gregory XVII.

1972-1977: The Apostles established missions in Guadeloupe, Puerto Rico, Guatemala, and the Dominican Republic.

1976 (June 26): A fire destroyed most of the buildings at St-Jovite.

1977-1978: The police and authorities made several raids at St-Jovite and Fr. John Gregory was arrested.

1978 (October 13): Fr. John Gregory was sentenced to two years in prison.

1980 (October 9): After many legal battles, Fr. John Gregory began to serve his prison sentence.

1981 (March 25): Fr. John Gregory was released from prison.

1983-1986: The Apostles established missions in Italy, France, Ecuador, and South Africa.

1999-2001: The police made new raids and investigated several members for abuses.

2001 (June 3): The charges against the members of the Order were dropped.

2011 (December 31): Fr. John Gregory died.

2012 (January): Fr. Mathurin de la Mère de Dieu–Mathurin of the Mother of God succeeded Fr. John Gregory as the Servant of the Church.

2012 (September 29): Fr. Mathurin was crowned with the name Gregory XVIII.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Les Apôtres de L’Amour Infini (the Apostles of Infinite Love) have their centre at the Monastery of Magnificat of the Mother of God in St-Jovite/Mont-Tremblant in the Canadian province of Quebec. [Image at right] Their goal is to preserve the traditional Catholic Deposit of the Faith, supplementing the Roman Catholic Church in an era of almost total apostasy. For five years, between 1962 and 1967, the Canadian group was part of the Renewed Church led from France by Michel Collin (1905-1974): Pope Clement XV. After that, they became independent, claiming to be the Renewed Church of Jesus Christ, led by Fr. John Gregory (Gregory XVII) until he died in 2011 and then by Fr. Mathurin (Gregory XVIII).

Gaston Tremblay, the future Gregory XVII, was born in 1928 in Rimouski in the province of Quebec. According to the hagiographies, aged twelve, Tremblay had a life-changing mystical experience. A statue of Our Lady spoke to him, saying, “My son has his company, and I shall have mine. You will work at it.” That meant that the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) already existed, while he should found a Society of Mary. In 1944, Tremblay joined the Hospitaler Brothers of St. John of God in Montreal where he worked with terminally ill patients. There he became Brother Jean Grande (Côté 1991; Magnificat January-February 1995 and September-Octobver 2012).

In September 1949, Fr. John received a new series of visions, one of which he described as a “half-hour long film.” In this movie-like experience, Christ told him: “The religious are no longer serving Me. I am going to raise up a new Order, and you will work at it.” The congregation that Tremblay should found would be both contemplative and missionary and the members should live in strict poverty. One crucial role model was Therese of the Child Jesus, the French contemplative Carmelite, who also was the patron saint of missions. The contents of the message were in the tradition of the apocalyptically centred Secrets given by the Virgin at La Salette in 1846 and Fatima 1917. According to them, the Roman Catholic Church would go through a severe crisis, and clerics on every level, even the highest, would apostatize (Magnificat, September-October 2012; Côté 1991).

In a vision, that he claimed to have experienced in 1950, Fr. John saw the face of a future pope, chosen directly by God. In this vision, Christ said:

Go and see the bishops, tell them I have asked you for an Order. This Order will preach the Gospel anew to the world with the power of the Apostles of the Early Church. It will be a tiny tree at first, but this tree will spread its branches over the world (Côté 1991:76).

Christ also told him: “you will become a priest, but one like me, when I walked the Calvary” and “you will become a bishop, but your mitre will be a crown of thorns.” To interpret his experience, Fr. Jean visited Henri Saey (1910–2006), a charismatic and controversial priest, who asserted that the revelation had a divine, not a diabolical origin. In 1952, just about to take his the permanent vows Fr. John left the Hospitalers to form a new community in the Rivière-des-Praires area outside Montreal (Côté 1991).

In 1953, the archbishop of Montreal Paul-Émile Léger (1904-1991) gave Fr. John permission to establish the Community of the Brothers of Jesus Mary. To mark the new beginning, he took a new religious name: Jean de la Trinité (Fr. John of the Trinity). The co-founders were Gilles de la Croix (1921–2006 and Leónard du Rosaire (1925–1997) (for their biographies see Magnificat March 2007 and April–May 1997 respectively). None of the three was ordained at the time, but they could count on the assistance of benevolent priests, who said Mass regularly. Nevertheless, the archbishop’s support soon waned considerably, considering them too extreme. It was the beginning of an extended period when the community tried to find a permanent place to live. The group consecutively attempted to settle within the borders of four Canadian dioceses, searching for approval by local bishops, but with little or no success (Côté 1991).

In 1958, the brothers acquired a farm near the small town of St-Jovite in the Laurentian Mountains some 120 kilometres northwest of Montreal. The local bishop accepted their presence in the diocese but did not consider them an ecclesiastically sanctioned religious community, but rather a group of “pious laymen.” However, the brothers stayed with the parish priest of Ham-Sud, Oblate father Maxime Brunet (later Jean-Marie du Sacré Coeur; 1912–2002) until 1961 when the rectory burnt down. By then, the local bishop wanted them out of his diocese, and they returned to St-Jovite (Magnificat June–July 2002).

For the Canadian community, the apparitions at Fatima were of paramount importance, and the Holy See’s decision not to make the contents of the so-called Third Secret of Fatima public in 1960 shocked them and many other Catholics. In 1961, Gaston Tremblay met Michel Collin, who recently had announced that he was Pope Clement XV, mystically elected by God. He argued that the Third Secret was a prophecy about his papacy that the Roman Catholic hierarchy wanted to hide. At their first encounter at the airport of Montreal, Fr. John claimed that Collin was the man he had seen in his papal vision, twelve years before. On his side, Clement contended that he had seen the Canadian in his revelations, and named him the “John the Baptist of the new times” (Magnificat October–November 2017).

According to the official biography, at first, Fr. John was somewhat reluctant to accept the French pontiff; it was a dramatic step to join a person put under general interdict. Therefore, he consulted the seer Gracia Thibault (1920–2012), [Image at right] who received messages from the Virgin under the title Mary, Mother of Salvation. After the consultation, he became convinced that Clement XV was the “Pope of Fatima” (Magnificat October-November 2017).

For several decades, the French priest Michel Collin had caused problems for the Roman Catholic authorities. In 1935, he had a vision of Christ consecrating him a bishop. According to this testimony, Collin was granted a position, potentially much higher than an ordinary bishop. He would become Christ’s principal Servant, the pope. On the same day, Christ instructed him to found L’Ordre des Apôtres de l’Amour Infini (the Order of the Apostles of Infinite Love). In the 1940s, Collin had a group of followers, who propagated the adoration of the Sacred Hearts of Christ and Mary. There was another part of the movement’s activities. Claiming direct orders from Christ, Collin founded a chain of foyers-cenacles, small house communities, where a consecrated host was on display at all times. He saw the movement as a restoration of the house churches of the apostolic times.

On October 7, 1950, Collin reported having had a grand vision that God the Father, who put a papal tiara on his head. The Holy See reacted rapidly. Through a decree, dated on January 17, 1951, the Holy Office reduced him to lay status, denouncing him for false teachings and revolt against church authorities and banned the Apostles of Infinite Love. The decree was reiterated in 1956 and 1961.

In 1960, the Apostles bought a piece of land in Clémery, Lorraine, where the “Small Vatican” was built. Collin made his papal claims in several increasingly public steps in the 1950s and early 1960s. He asserted that he was a co-pope, assisting Pius XII until he died in 1958. He also claimed to hold that position during the pontificate of John XXIII (sed. 1958‒1963). In his view, the Roman popes could not act freely due to the opposition from many  modernist and masonic members of the Curia. On March 25, 1961, Collin officially declared that he was Pope Clement XV, [Image at right] and a week later he established L’Église Catholique Renovée (the Renewed Catholic Church). It was also referred to as the Church of Glory, the Church of Miracle, the Mystical Church and the Church of the Resurrection (on Michel Collin/Clement XV, see Heim 1970; Kriss 1972; Delestre 1985; and Lundberg forthcoming.)

modernist and masonic members of the Curia. On March 25, 1961, Collin officially declared that he was Pope Clement XV, [Image at right] and a week later he established L’Église Catholique Renovée (the Renewed Catholic Church). It was also referred to as the Church of Glory, the Church of Miracle, the Mystical Church and the Church of the Resurrection (on Michel Collin/Clement XV, see Heim 1970; Kriss 1972; Delestre 1985; and Lundberg forthcoming.)

In January 1962, Fr. John travelled to Clémery, where Pope Clement ordained him to the priesthood. A few months later, he was consecrated a bishop and made a cardinal, and towards the end of the year, the pope ceded the title of prior general of the Order of the Mother of God to him. When Pope John XXIII died in June 1963, Clement announced that he was the only true pontiff and that Jesus, Mary, and Joseph placed the papal tiara on his head. Clement denounced Paul VI publically, naming him an anti-pope and apostate. He also convened a Council at Lyons in September 1963, a kind of Anti-Vatican II (Côté 1991, cf. Magnificat October–November 2017).

In 1962, a group of Canadian Roman Catholic bishops denounced both Clement XV and the community in St-Jovite, and the local bishop of Mont-Laurier placed an interdict on them warning Roman Catholics of the group:

These persons are not brothers, and even less priests, and any semblance of a Mass celebrated or sacraments administered by them is sacrilegious. We have decreed and do decree that under pain of being denied the sacraments, it is forbidden for any family and any individual residing in our diocese to receive, lodge, visit or encourage in any manner whatsoever by donations or otherwise, the above-mentioned Brother John and his disciples (La Presse, May 17, 1962).

Still, during the first half of the 1960s, an increasing number joined the Canadian community, which opened up for women, too. In 1962, only seven people lived at St-Jovite. In 1963, they were thirty and in 1964, about ninety. Two years later, the number of inhabitants exceeded 300, including both religious and laypeople. They started to construct a large monastery. The goal was to be self-supporting, and with the influx of new members and donations, they could acquire other farms in the province. Apart from the community members, many other adherents lived spread over Canada and the United States. Just as in Europe, they were organized in cenacles, which housed home altars with the Blessed Sacrament on constant display. Given the rapid development, not surprisingly, Pope Clement saw Canada as the Renewed Church’s most important mission field. Between 1961 and 1966, he made ten North American journeys (Normandeau and Désy 1964; Côté 1991; cf. Magnificat October–Novmeber 2017).

Many of the people who settled in St-Jovite had children; in some cases, even infants. The presence of children in a remote, religious community was controversial. The Apostles saw the presence of children as a means to save them from the sins of the modern world. The 1960s was the time of the ‘Quiet Revolution’ in the province of Quebec, during which secularization and the change of gender roles were rapid, and an increasing number of schools and hospitals moved from church to government. The Apostles were part of the protest against this development, but also against the changing Roman Catholic Church.

From December 1966 onwards, the police and the social authorities made several raids and inspections at St-Jovite following reports about mistreatment of children living there. However, as the first raid was announced in advance, most children were sent away to other places, including the homes of followers and supporters. They became known as “the Hidden Children of St-Jovite.” Eventually, in February 1968, the Superior Court of Quebec overruled the Social Welfare Court’s decision, and the children returned to the monastery (For details about the raids and the legal battles, see below under Issues/Challenges).

Shortly after the first police raid, on January 21, 1967, Clement XV suspended Fr. John [Image at right] as the superior and bishop of Canada “for civil and religious irregularities and his subordination and abuse of confidence.” According to recent publications by the Canadian Apostles, Pope Clement acted in this way because he was “deceived by bitter enemies of the Canadian Work,” found among his closest men in France. Fr. John went to Europe to discuss the matter with Clement, but the latter did not show up at the planned meeting. After the permanent split between St-Jovite and Clémery, most of the Canadian apostles remained with Fr. John (Côté 1991; Magnificat November-December 2017.)

Still, even before that time, there was a growing rift between the Canadian and European Apostles as Clement XV introduced several dramatic doctrinal changes. He announced the inauguration of the era of the Third Testament on February 2, 1966. In this epoch, the private revelations to Clement would be even more essential, and it became the beginning of a much more rapid dogmatic development. In the new teachings, Planetarians, benevolent peoples from other planets who visited earth, played an essential part in salvation history. Through their intercession, God had decided to postpone the Last Judgement, while it was still imminent (Lundberg forthcoming).

The Canadian Apostles have continued to recognize Clement as having been a true pope. However, they state that he was ‘hypersensitive, dominated by his own emotions and easily influenced and unpredictable,” that he issued “absurd dogmas,” and even that he was both “divine and diabolical ”(Côté 1991:206–10). In a heavenly message to the seer Gracia Tribault on February 11, 1968, Mary, the Mother of Salvation, stated: “You no longer have a pope!.” In a 1980 interview, Fr. John stated:

Little by little, [God] asked me if I would take charge of the Church. First He told me, ‘You will serve the Church,’ and then He told me sometime later, ‘You must proclaim the name of the Servant of the Church, Gregory XVII.’ So I obeyed and proclaimed it (Questions and Aswers 1989:2)

In later writings, Fr. John declared that God elected him the leader of the Chuch on June 24, 1968. Still, according to the testimony, Christ did not call him pope, but Shepherd of the Church and gave him the name (Jean)-Grégoire XVII, (John)-Gregory XVII. Still, he would seldom use the papal name, but Fr. John Gregory of the Trinity or just Fr. John Gregory. According to the Canadian Apostles, Clement XV accepted this development already in August 1968; the official publications of the French apostles, however, do not corroborate this version. The Canadian Apostles have a postcard dated May 9, 1969 in which Clement XV wrote that he had realized that Heaven had chosen Fr. John as his successor (Côté 1991:211). The document seems to indicate that Clement had received a divine message stating that God had chosen Fr. John as the Pope. Clement’s note is hand-written and does not have a letter-head. Moreover, it is not entirely clear if Clement understood the Canadian as a mere a co-pope, as he had been during part of the pontificates of Pius XII and John XXIII, or if Fr. John now was the only Vicar of Christ.

In the early 1970s, the Apostles published several books that argued that Fr. John was the “Servant of the True Church of Jesus Christ.” They continued to claim that due to its apostasy, the Holy See was not in Rome anymore, but that it had left Clémery, too, and for similar reasons. The argument was mainly based on nineteenth and twentieth-century apparitions and in particular the Secrets of La Salette, but also on a comparison between the pre- and post-Vatican II teachings. The titles include Peter is Not in Rome (1970), The Eclipse of the Church (1971) and When a Prophecy Comes True or “Rome Will Lose the Faith” (1972). These and many other of the Apostles’ texts were written by Mère Michelle du Coeur Eucharistique de Jésus (1938-2017). The most substantial work of this kind, however, is Catherine St-Pierre’s 950-page volume Thou art Peter (1994), where she presents a significant number of older and modern prophesies that the Apostles believe precluded the papacy of Gregory XVII.

On September 29, 1971, a group of eight bishops crowned Fr. John Gregory at St-Jovite. In later interviews, he claimed that he did not want to be crowned, but that he had sought to make the community happy. According to his testimony, the tiara was not an expensive piece but made of papier-mâché (Catherine St-Pierre 1994). In interviews, he was reluctant to call himself pope. Still, his position was indeed just that, though temporary.

At the present time, I occupy the posts of Prior Major of the Order of the Apostles of Infinite Love and Servant of the Church. The person in charge of the Church bears the title of Servant. The combination of these two posts is a temporary thing (Catherine St-Pierre 1994).

Hearing the news about the coronation, Clement XV excommunicated Fr. John Gregory, through a decree, dated June 29, 1972 (Schubert 1995, Volume 4). The official historiography of the Canadian Apostles does not include this event. Still, given Clement’s erratic behaviour during the late 1960s and early 1970s, both his acceptance of Fr. John Gregory as a true pope in 1969 and the ex-communication decree from 1972 could very well be true.

From the early 1960s, the Order of Magnificat of the Mother of God [Image at right] consisted of male and female religious, who took permanent vows on poverty, chastity, and obedience. They adopted the Rule for the Apostles of the Latter Times, which they believed was dictated by Our Lady at La Salette in 1846. From the beginning, married people could also take the vows and become brothers and sisters, though it, of course, meant that they lived separately. Still, as the Order of the Mother of God is as a federation of religious orders, there were also Carmelites, Franciscans, and Grey Sisters among the nuns (Côté 1991).

However, there were lay celibate or married people who did not take permanent vows but lived in a similar vaw. They were called disciples. Outside of St-Jovite and some other centers lived the lay members, who belonged to the Third Order of the Apostles. Already in 1962, the Apostles of Infinite Love was registered as an official corporation in Canada. Still, it was not until the early 1970s that they got the status as an officially recognized religious group, first in the province of Quebec in 1971, then two years later on the federal level, too (The Gazette September 8, 1973).

The Apostles’ center in St-Jovite is not only a monastery; it is also a theocratic monarchy: the Royaume de L’Amour Infini de Jesús Crucifié (The Kingdom of the Infinite Love of the Crucified Christ). Following a long French prophetical tradition, the renewal of the papacy with Clement XV and Fr. John Gregory also involved the restoration of the French monarchy. Thus as the Servant of the Church Fr. John Gregory crowned a disciple, Louis Douziech, the King of France (see the documentary, Mon Père le Roi).

The size of the monastic community probably reached its peak during the first half of the 1970s. But in 1976, the Apostles underwent a great crisis. On June 26, most of the buildings at St-Jovite burnt down to the ground. [Image at right] Only the priests’ house remained intact. According to the press, a lightning bolt caused the fire, while the Apostles claim that it was arson. The monastery was rebuilt in the years to come (The Gazette June 28, 1976; cf. Palmer 2020b).

Though the Monastery of Magnificat of the Mother of God in St-Jovite was the unquestionable centre of the Church, from the late 1960s onwards, the Apostles opened up missions in other parts of Canada: Montreal, Quebec City, Ontario, Toronto, Winnipeg, Edmonton and Vancouver. They were also present in the United States, for example, in New York, New Jersey and Florida.

Outside of North America, the Apostles had a quite strong presence on some Caribbean islands, and in a few Latin American countries. Their first attempt to gain a hold was in Haiti, but due to the country’s concordat with the Holy See, they had to abort the mission. In the following years, the Apostles established missions in Guadeloupe (1972), Puerto Rico (1975), Guatemala (1976) and the Dominican Republic (1976), mainly working among impoverished people (See, The Gazette April 11, 1969; Côté 1991; www.magnificat.ca).

The mission in French Guadeloupe was particularly influential. In 1976, the Apostles established two convents there. One was located in the highlands and the other close to Point-a-Pitre. The latter grew into a famous pilgrimage site. In 1977, a fourteen-year-old girl claimed to receive messages from Our Lady of Tears. She lamented the apostasy of the Roman Catholic Church. For the Apostles, the apparitions became an essential link in the chain of Marian interventions in the End-Time, including La Salette, Fatima, Garabandal, and Mary, Mother of Salvation (Magnificat, November-December 2017; cf. Hurbon 2001).

The events in Guadeloupe are related to the publication of an important book: Saul, why do you persecute me? (1977) by Michel di San Pietro. Still, once again the real name of the author was Mère Michelle du Coeur Eucharistique de Jésus. In the book, she analyzed texts published by Paul VI, arguing that under his leadership, the Roman Church was not Catholic anymore. The church authorities had founded a new religion, which focused on humanity, not on God, making the 1948 Declaration of the Rights of Man into a sacred text. Like many similar groups, the Apostles thought that the United Nations was the Masonic organization par excellence.

As a response to this grave situation, Our Lady of Tears had urged the Apostles to hand over an “ultra-secret message” to Paul VI. Towards the End of 1977, the young seeress from Guadaloupe, Mère Michelle, and two other nuns travelled to Rome. There, they distributed the book to many different Roman institutions. They also succeeded in placing a copy of the book on an altar in the St. Peter’s Basilica. Not achieving their goal to get a personal audience with Paul VI, they attended a general audience, where they managed to come close to the pope shouting that he should listen to what they had to tell him. After leaving Rome, the group travelled to Paris, where they tried to arrange a private meeting with the president Valéry Giscard D’Estaing. Not being successful, they left him a letter, which called for the conversion of France, closely following the secret of La Salette (Magnificat, July-September 2019).

Beginning in 1978, the Apostles became the centre of attention for both the authorities and the Canadian press. Once again the police and the authorities raided the Monastery in St-Jovite on several occasions. This time, too, it had to do with “hidden children” and a custody case. At the trial, Fr. John Gregory was sentenced to prison for sequestration for not disclosing the whereabouts of two children (For details, see Issues/Challenges below).

From the 1980s onwards, the Apostles continued their work in Canada, the United States and several countries in the Caribbean and Latin America. Beginning in 1986, they established missions in several places in southern Ecuador. During the 1980s, they also founded small communities in Italy, France, and South Africa. Still, the Canadian authorities were very sceptical of the Apostles and sometimes refused the entry of foreign members into the country or subjected them to hard enquires (Palmer 2020b).

Around the turn of the millennium, the Apostles once more made front-page news as a group of people who had grown up at the monastery pressed charges of physical and sexual abuse against four religious, including Fr. John Gregory. The monastery was raided once more, but in the end, the case was closed as evidence had disappeared (for details, see Issues/Challenges below).

Fr. John Gregory, who had been severely ill for several years died on December 31, 2011. Several years before his death, he chose Fr. Mathurin de la Mère de Dieu (Michel Lavallée), [Image at right] a bishop and cardinal, as his successor and claimed that he acted according to the will of God. Fr. Mathurin was born at St-Jovite in 1962. Shortly after, both his mother and father joined the Order, and later his sister became a nun. In January 2012, Fr. Mathurin became the Servant of the Church under the name Gregory XVIII though this name is seldom used. On September 29, 2012, he was crowned, but that was a very low-key ceremony, as the Apostles did not want any media attention. For a long time, it was not easy for an outsider to know that Fr. Mathurin was regarded as the Servant of the Church, though he was the superior general of the Order. Still, by 2020 new texts on the website makes it much more apparent than before (On Fr. Mathurin’s background, see the biography of his father Jérome de la Resurrection in Magnificat, April 2020).

By 2020, the Apostles had convents and chapels in Montreal, Quebec City and Toronto. The presence of the Apostles in the United States is concentrated to New Jersey, New York City, Florida and Colorado. Outside North America, the community of Guadeloupe remains the biggest with almost forty priests and religious. In Puerto Rico, Guatemala, Ecuador and the Dominican Republic, there are small communities and chapels. There are also small missions in France, Italy and South Africa, and as late as 2016, a new mission was established in Buenos Aires.

There are no official data on the priests, male religious and nuns. At my visit to Mont-Tremblant, there were at least seventy or eighty male and female religious present at the conventual Mass. The group includes both long-time and younger members. The Apostles take a vow not to disclose anything about their past. Therefore, an outsider cannot know anything sure about their origin. Still, many of the younger seem to be from Guadeloupe and Ecuador. My estimate of the total number is somewhere between 150 and 200.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The Apostles of Infinite Love and the Order of the Mother of God were founded to preserve the traditional Catholic faith, which they thought was seriously threatened by the modernist development in the Roman Catholic Church, where most bishops and priests had apostatized. They claimed that this development began well before the Second Vatican Council. Just as Clement XV, the Canadian Apostles were extremely critical of Paul VI claiming that he was elected through a curial conspiracy of freemasons. In short, he was an anti-pope (John Gregory of the Holy Trinity 2012).

The Apostles’ theology has a millennialist focus. It is based on the expanding canon of apocalyptic beliefs, prophecies and Marian apparitions that has influenced nineteenth and twentieth-century Catholicism. They are not part of official Roman Catholic teaching but often counteracted by the local bishops and the Holy See. Still, the ideas are popular and influential, not least among traditionalists who believe that the Roman Catholic Church has degenerated. They think that the Roman Catholic Church has apostatized, and await the appearance of a Great Pope who will save the Church.

The apocalyptical canon includes mystics such as Anna Catharina Emmerich (1774-1824), Anna Maria Taigi (1769-1837) and Bartolomäus Holzhauser (1613-1658), and the Secret given by the Virgin to Melanie Calvet (1831-1904) at La Salette in 1846. They all claimed that the Roman Pope would apostatize and that, in the End-Time, both a pope and an anti-pope would appear. The apocalyptic canon also includes texts that detail the future. Paramount among them are Prophecies of Saint Malachy, attributed to an eleventeenth-century Irish bishop but  written in the late 1500s, and the texts of the so-called chronicle of the Monk of Padua, printed towards the eighteenth-century. Catherine St-Pierre’s Thou Art Peter (1994), [Image at right] published by the Apostles of Infinite Love, is a 950-page book that use this prophetical corpus and many other texts to prove the End-Time papacy Gregory XVII (and the papacy of Clement XV).

written in the late 1500s, and the texts of the so-called chronicle of the Monk of Padua, printed towards the eighteenth-century. Catherine St-Pierre’s Thou Art Peter (1994), [Image at right] published by the Apostles of Infinite Love, is a 950-page book that use this prophetical corpus and many other texts to prove the End-Time papacy Gregory XVII (and the papacy of Clement XV).

In the Apostles’ view, at least since the French Revolution the Roman Catholic Church degenerated gradually through the presence of Freemasons among the bishops, including the Curia. In the end, “Rome lost the Faith,” and the Cardinals elected an anti-pope: Paul VI. While Freemasons are the biggest enemy, anti-Judaism it is clear as the Apostles see the Protocols of the Elders of Sion as real.

In this era of near general apostasy, God intervened and chose popes directly: first Clement XV and then Gregory XVII. In the Apostles’ view, their pontificates constituted the advent of what the French mystic Louis-Marie Grignion de Montfort (1673-1716) called the Reign of Christ through Mary employing the Apostles of the Latter Times. And in the End-time, the Apostles of Infinite Love and the Renewed Church is an Ark of Salvation for the faithful remnant in an era of darkness and faithlessness (St-Pierre 1994, on Catholic millennialism and prophecy, cf. Airiau 2000 and Introvigne 2011).

The teachings of the Apostles of Infinite Love are explained in several other texts, too. In 1975, Fr. John Gregory, Gregory XVII, published an almost 300-page encyclical called Peter Speaks to the World, [Image at right] which includes his comments on the sins of humanity and very harsh criticism of the post-Vatican II church developments. Still, the focus of the encyclical is on Church reform, not on apocalyptics. Thus, apart from the question of whom was the true pope, little differs from Roman Catholic teachings, at least before Vatican II, though there are significant differences too. Not least after the Council, there was a great need for priests. In the Roman Catholic Church, many had left the priesthood, and few became seminarians. Fr. John Gregory made it clear that married men could be ordained priests. It is, however, interesting to note that the encyclical does not mention the ordination of women, though the Apostles ordained nuns, too.

Fr. John Gregory devoted a substantial part of the encyclical to social issues. Most of the contents build firmly on traditional Catholic Social Teaching from Leo XIII onwards. On the one side, he points to the threat of Socialism and Communism, and on the other to the unlimited capitalist economy, which creates an unjust distribution of goods. He favoured the creation of cooperatives and communities as ways to greater equality. He asserted that men and females have different roles in the family and society. To him, the best way to form good Christians is to entrust their education to monasteries. The encyclical also emphasized private virtue. He wants to regulate the sale of alcohol, and he includes a long and hard denunciation of tobacco use as well as a general condemnation of organized sports, which he saw as the worst modern-day idolatry.

In 1997, the St-Jovite community published the Catechism of Catholic Christian Doctrine: Taught by Jesus Christ and the Apostles. It is an easily accessible text, which built on the official late-eighteenth-century Canadian and Baltimore catechisms, which in their turn are based on the Catechism of the Council of Trent. Still, the Apostles’ version included much more direct biblical quotations. The hope for humanity would be a revival of the Catholic Church of Jesus Christ. The primary building stone should be prayer and penance, and Fr. John emphasized the importance of religious images, home oratories, and if possible, daily Mass attendance. However, due to its apostasy, the sacraments of the Roman Catholic Church was not valid anymore. Also in this work, the usual Order was broken by two lengthy denunciations of tobacco use and organized sports, respectively.

The texts published by the Apostles through Éditorial Magnificat includes sermons and teachings by Fr. John Gregory, Fr. Mathurin and other members of the Order. Still, above all, they publish edifying texts on nineteenth and early twentieth-century holy people. The hagiographies focus on martyrdom and vicarious suffering. They include books about well-known saints such as Therese of the Jesus Child (1873-1897), but also less known persons such as the Palestine Carmelite Mary of Jesus Crucified (1846-1878), the Vietnamese Brother Marcel Van (1928-1959), and several French and Canadian children who died very young, showing great piety and stoicism in their suffering.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The rituals of the Apostles of Infinite Love are similar to traditional Roman Catholic use, including the rites of the seven sacraments. Apart from that, processions, and other traditional forms of piety such as novenas, the rosary, and sacramental adoration play central roles. Though the Apostles criticized the New Mass Order, promulgated by Pope Paul VI in 1969, they were in favour of a simplified liturgy and said the Mass in the vernacular from the very beginning.

The priests of the Order of the Magnificat of the Mother of God say two forms of Mass: the Conventual Mass and the Brief Mass. The Conventual Mass bears a clear resemblance to the Tridentine Order of the Mass, though it said in the vernacular. Still, most of the sung prayers are in Latin as are the words of consecration. Unlike the Tridentine Mass, there is a high degree of interaction between the priest and the community. The whole community reads most of the texts together; the priest just starts. However, only the celebrating priest says the words of consecration. Conventual Mass is followed by the rosary alternately prayed in Latin, French, English and Spanish (personal observations, 2019).

The priests can say the Mass in private several times a day according to the Brief Order of the Mass, which is regarded as a condensed Tridentine version. The ordained nuns only say Mass privately as do most of the ordained males. Most of the text in the vernacular, but some parts still in Latin, most importantly the words of consecration (Brief Order of the Mass n.d.).

From the 1960s onwards, the Apostles of Infinite Love has ordained women to the priesthood. The Renewed Church under Clement XV also consecrated women bishops, but the Canadian Apostles have not. Michael Cuneo (1997) claimed that by the mid-1990s about a third of the nuns at St-Jovite was ordained. Today most of the nuns are. Still, there are differences between male and female priests. Women only say Mass privately or sometimes in groups of women. Only under exceptional circumstances, when no male priest is present at a mission, women can say Mass in public. However, most of the male priests rarely say Mass in public. Some of the ordained nuns can also take confession and act as spiritual advisors (Personal observations, 2019).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The Apostles of Infinite Love/The Renewed Church of Jesus Christ is led by the (Universal) Servant of the Church of Jesus Christ, which has the role of a pope, though the Apostles do not use the word. After splitting ways with Clement XV Gregory XVII (Fr. John Gregory) held the office from 1968 until he died in 2011, and after that Gregory XVIII (Fr. Mathurin) has upheld the office. The Servant of the Church is also the Superior General of the Order of Magnificat of the Mother of God (ODM), which has male and female members. The male branch includes bishops, some of whom are cardinals, but also priests and brothers.

A mother superior, under periods referred to as abbess, leads the female branch of the Order. For several decades, Mère Germaine de la Resurrection (Germaine Garand, 1921–2011) held this position. In 1968, Fr. John Gregory named her, a mother of thirteen children, Superior General of all the sisters of the Order, and in 1989, he  consecrated her abbess, a position she held until her death at the age of ninety, though with assistance the last years (Magnificat: February–March and April-May 2014.)

consecrated her abbess, a position she held until her death at the age of ninety, though with assistance the last years (Magnificat: February–March and April-May 2014.)

As seen, Mère Michelle du Coeur Eucharistique de Jésus [Image at right] was a very central person in the history of the Apostles, not least in their international missionary work. She was editor of, and principal contributor to Magnificat and author of the lion’s part of the books that the Apostles published from the late 1960s onwards. During the lengthy legal processes against the Apostles and Fr. John Gregory, she was the leading spokesperson. Thus her role in the history of the Apostles could hardly be overstated.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Apart from a few years in the early 1950s, the community that Fr. John founded, which later became the Apostles of Infinite Love were criticized and denounced by the local Roman Catholic authorities. After 1962, when they joined the Renewed Church of French Pope Clement, an interdict was placed upon them. That meant that Roman Catholics were not allowed to take part in any religious services held by the Apostles, as they were a dissident group. Still, as I have indicated, the most publicized issues concerning the Apostles involved the presence of children at St-Jovite. The three most intense periods were 1966-1968, 1977-1980 and 1999-2001, respectively. They included both federal and state authorities and courts on different levels. This part is based on the Apostles’ publications and two Quebecois dailies: The Gazette of Montreal and La Presse of Quebec 9 (cf. Palmer 2020b). For a more general view of the Apostles and their place in Quebecois society (See Vaillancourt 2000, Geoffroy & Vaillancourt 2001, Campos & Vaillancourt 2006, and Geoffroy 2009). The Apostles published two books on the legal battles between 1966 and 1968: When Bad Faith Hides behind the Law (1968) and the more detailed Father John of the Trinity and the Hidden Children of St. Jovite (1971).

Many of the people who settled in St-Jovite and became members of the Order had children. The presence of small children in a remote, religious community was controversial. It began with some individual custody cases between spouses. The typical situation was that both parents had become members, but that one of them left the community, and the children stayed, or that one parent had left for St-Jovite, bringing children with him or her. In other cases, other relatives were concerned with the children’s wellbeing. On their hand, the Apostles saw the presence of children at St-Jovite as a means to save them from the sins of the modern world.

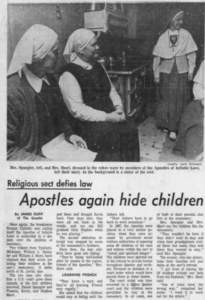

The local social welfare authorities gathered information about the children at St-Jovite and prepared to act. On December 28, 1966, around fifty policemen raided the church compound. Still, knowing that something was about to happen, by then, the Apostles had moved most of the children from St-Jovite and placed them in homes of adherents and sympathizers in Canada and the United States. “The Hidden Children,” as they were called in the media, [Image at right] numbered about eighty.

In mid-January 1967, the Social Welfare Court in St-Jerôme ordered Fr. John to disclose the whereabouts of the children, but he went into hiding, and the police issued a search warrant for him. At the official visits at St-Jovite, the judge and his assistants found no concrete evidence of harmful living conditions. Still, they stressed that the children must attend a public school as the teaching was of poor quality and almost totally focused on religious instruction.

During the raid in January 1967, the police seized documents, where addresses of outside members and sympathizers appeared, and they began to search for the children on those locations. In the next couple of weeks, the police encountered between twenty and thirty of the children and made a new raid at St-Jovite, but most were not found. A medical doctor examined the returnees and concluded that they were healthy and showed no signs of physical mistreatment. On September 27, 1967, police forces made a new extensive raid at St-Jovite, searching for evidence, and taking the seven children they encountered in custody as they were in “moral and physical danger.” A month later, Fr. John returned after nine months in exile, and soon after he was arrested for not disclosing the whereabouts of the thirty children who remained hidden.

Eventually, in February 1968, the Superior Court of Quebec overruled the Social Welfare Court’s decision and stated that it lacked jurisdiction and legal grounds. As a result, all children could return to St-Jovite. The Apostles persistently claimed that the authorities only persecuted them because they were religiously different and that they were in the hands of the Roman Catholic Church.

The second period of raids, arrests and legal battles took place between 1977 and 1981. The Apostles’ description of the events is found in the book “Justice” Put on Trial by the Apostles of Infinite Love (1984). It was complemented by news reports from the two Quebecois dailies: The Gazette and La Presse. This time the police made two main raids at St-Jove in search of two children, whose father had left the Apostles, but whose mother remained. The first was massive and included a dozen police cars and two helicopters. In all, during 1977 and 1978, police did searches at St-Jovite on at least thirty occasions, something that the Apostles saw as pure harassment. The mother of the children was the first to be convicted, but on April 25, 1978, Fr. John Gregory was arrested, too, accused of sequestration of the two children, and was held in custody for four months.

In late June 1978, the first trial of Fr. John Gregory began. He was charged with contempt of court, as he did not disclose the whereabouts of the two children, and on August 10, he was sentenced six months in prison. Later that year, there was a second trial. He was charged with sequestration of the two children, and, in the end, sentenced to two years in jail. The defence appealed to the Supreme Court, and in the meantime, Fr. John was released on bail.

1978 was the year of the Jonestown mass suicide-murder. In the Canadian press, anti-cult activists and politicians drew parallels between Jonestown and St-Jovite and saw potential risks. Some argued that the government should hire “deprogramming specialists” as the members of the Apostles were victims of “brain-washing” from the leadership. On their part, the Apostles protested again what they saw as harassment and religious persecution. In the end, the Canadian Supreme Court decided not to re-examine the case, and on October 9, 1980, Fr. John went to prison to serve his two-year sentence. The National Parole Board, however, decided to release him much earlier, and on March 25, 1981, he left prison.

The third extensive police investigation took place around the turn of the millennium. At that time, at least sixteen former members who had grown up in the community filed complaints. The file included thirty charges about different kinds of abuse made by two nuns and two priests, including Fr. John Gregory. The points of accusation included cases of physical violence and sexual abuse committed between the mid-1960s and mid-1980s. As part of the investigation, in April 1999, there was a vast police raid at St. Jovite. It included about 100 police officers, but they did not encounter the four accused persons. At the time, around 200 people lived in St-Jovite, including nineteen children who the authorities took into custody.

During the investigation, other ex-members give testimonies of abuse. Many of them grew up at St. Jovite but left as young adults. In the community, even very young children were separated from their parents who took vows. While living in the same compound, they hardly ever met their parents. In the case of children over ten, such meetings were arranged only a couple times a year, and then only for short a few hours. While some of the married apostles had many children, the siblings also rarely met. The young girls were raised by nuns and the boys by male religious, so brothers and sisters did not meet each other. Another division was according to age groups, and thus, many of the children did not meet their siblings very often. Some ex-members testified that children often were severely and frequently beaten, or otherwise mishandled and humiliated by male and female religious. There were also testimonies about sexual abuse.

After the raids and investigations, the persecutor decided that the case would not hold in court, particularly as most of the crimes should have been committed many decades ago. Moreover, the investigation was complicated by the older evidence material related to the Apostles had disappeared from the social authorities’ archives. Eventually, on June 3, 2001, the charges against Fr. John Gregory and the three other religious were dropped. Still, as a direct effect of the investigation, the State of Quebec passed a law that prohibited persons under the age of sixteen from living in a monastic community.

IMAGES

Image #1: The Monastery of Magnificat of the Mother of God in St-Jovite/Mont-Tremblant.

Image #2: .Mrs. Gracia Tribault (1920-2015).

Image #3: Pope Clement XV, 1960s.

Image #4: Fr. John Gregory in the late 1970s.

Image #5: Order of Magnificat of the Mother of God coat of Arms.

Image #6: Monastery at St-Jovite before the fire.

Image #7: Fr. Mathurin de la Mère de Dieu, Gregory XVIII, Corpus Christi, 2018.

Image #8: Catherine St-Pierre, Thou art Peter (1994).

Image #9: Peter Speaks to the World (1975).

Image #10: Mère Michelle du Coeur Eucharistique de Jésus.

Image #11: Press clipping from The Gazette, 1970.

REFERENCES

Airiau, Paul. 2000. L’Église et l’Apocalypse du XIXe siècle à nos jours. Paris: Berg International.

Brief Order of the Mass, n.d. St-Jovite: Éditions Magnificat.

Catechism of Catholic Christian Doctrine: Taught by Jesus Christ and the Apostles. 1997. St-Jovite: Éditions Magnificat.

Catherine St-Pierre. 1994. Thou Art Peter, St-Jovite: Éditions Magnificat.

Campos, Élisabeth and Jean-Guy Vaillancourt. 2006. “La régulation de la diversité et de l’extrémisme religieux au Canada.” Sociologie et sociétés 38:113‒37.

Côté, Jean. 1991. Father John of the Trinity, Prophet without Permit. Second Eiditon, St-Jovite: Éditions Magnificat.

Cuneo, Michael W. 1997. The Smoke of Satan: Conservative and Traditionalist Dissent in Contemporary American Catholicism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Delestre, Antoine. 1985. Clement XV, prêtre lorrain et pape à Clémery. Nancy & Metz: Presses Universitaires de Nancy & Éd. Serpenoise.

Father Jean de la Trinité and the Hidden Children of St. Jovite. [1971] 1999. Third Edition. St-Jovite, Éditions Magnificat.

Geoffroy, Martin. 2009. “L’intégrisme catholique schismatique de type mystique-ésotérique: Le cas des Apôtres de l’Amour infini.” Pp. 219-240 in La Religion à l’extrême, edited by Martin Geoffroy and Jean-Guy Vaillancourt. Montreal: MédiasPaul.

Geoffroy, Martin and Jean-Guy Vaillancourt. 2001. “Les groupes catholiques intégristes: Un danger pour les institutions sociales?” Pp. 127-41 in La peur des sectes, edited by Jean Duhaime and Guy-Robert St-Arnaud. Montréal: Les Éditions Fides.

Gregory XVII. [1975] 1993. Peter Speaks to the world, 2nd edition, St-Jovite: Éditions Magnificat.

Heim, Walter. 1970. “Die ‘Erneuerte Kirche’: Papst Clemens XV. in der Schweiz.” Schweizerisches Archiv für Volkskunde/Archives suisses des traditions populaires 66:41–96.

Hurbon, Laënnec. 2000. “Les Nouveaux Mouvement Religieus dans les Carïbe.” Pp. 307‒54 in La phénomè religieux dans la Caraïbe, edited by Laënnec Hurbon. Guadeloupe, Martinique,:Guyane, Haïti, Paris: Les Editions Karthala.

Introvigne, Massimo. 2011. “Modern Catholic Millennialism.” Pp. 549-66 in Oxford Handbook of Millennialism, edited by in: Catherine Wessinger. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

John Gregory of the Trinity. 2012. A Supplemental Role: Extracts from Radio Interviews in which Father John Gregory Explains his Name Gregory XVII and His Role, as Well as the Role of the Order of the Mother of God. Mont-Tremblant: Éditions Magnificat.

“Justice” put on trial by the Apostles of Infinite Love. 1984. St-Jovite: Éditions Magnificat.

Kriss, Rudolf. 1972. “Die Domäne, Marie-Corédemptrice in Clémery, genannt. Der Kleine Vatikan, und ihr Hausherr, Papst Clemens XV.” Pp. 346–80 in Volkskunde: Fakten und Analysen. Festgabe für Leopold Schmidt zum 60. Geburtstag, edited by Klaus Beitl. Vienna: Selbstverlag des Vereines für Volkskunde,

Lundberg, Magnus. Forthcoming. Could the True Pope Please Stand Up: Twentieth and Twenty-First Century Alternative Popes.

Marie-Claire. [Mère Michelle du Coeur Eucharistique de Jésus], Agent ES-1026. The Most Incredible Conspiracy of Our Times [1974] 2019. Second Edition. Mont-Tremblant: Éditions Magnificat.

Michel San Pietro. [Mère Michelle du Coeur Eucharistique de Jésus], [1977] 1991. Saul, Why Do You Persecute Me? Third Edition. St-Jovite: Éditions Magnificat.

[Michelle du Coeur Eucharistique de Jésus] 1972. When Prophesy a Prophesy Comes True. St-Jovite, Éditions Magnificat

[Michelle du Coeur Eucharistique de Jésus] 1971. The Eclipse of the Church. St-Jovite: Éditions Magnificat.

[Michelle du Coeur Eucharistique de Jésus] 1970. When Peter is not in Rome, St-Jovite, Éditions Magnificat.

Normandeau, André and Jacques Désy. 1964. “La secte de Saint-Jovite: Un phénomène de pluralisme vertical”, Cité libre, May 22‒27.

Palmer, Susan J. 2020. “The Apostles of Infinite Love and the ‘Hidden Children’ of Saint-Jovite.” Pp. 193–216 in The Mystical Geography of Quebec: Catholic Schisms and New Religious Movements, edited by Susan J. Palmer, Martin Geoffroy and Paul L. Gareau. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Questions and Answers on the Apostles of Infinite Love: The Order of the Magnificat of the Mother of God of St. Jovite. 1989. St. Jovite: Éditions Magnificat.

Rigal-Cellard. Bernadette. 2005. “Le future pape est québecois: Grégoire XVII.” Pp. 269–300 in: Missions extremes en Amérique du Nord: Des Jésuites à Raël. edited by Bernadette Rigal-Cellard. Bordeaux: Édition Pleine Pages.

Schubert, Reinhard. 1995. Quid et Unde?: Kritisches Hilfsbuch zum Studium der apostolischer Weihesukzession der Bischöfe in kleineren Kirchen und Gemeinschaften, 4 volumes. Bremen: R. Schubert.

Vaillancourt, Jean-Guy. 2000. “Les stratégies sociales des groups catholiques de droite au Québec”, Religiologiques 22:39–56.

Publication Date:

22 June 2020