MOVE TIMELINE

1931: Vincent Lopez Leaphart, who would become John Africa, was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

1968: Vincent Leaphart began compiling a manuscript that would become The Guidelines of John Africa.

1972: The early members of MOVE began meeting to discuss The Guidelines of John Africa.

1973: MOVE people purchased 309 North 33rd Street in the Powelton Village neighborhood of West Philadelphia. The house served as the first MOVE headquarters.

1976: MOVE people Janine and Phil Africa’s newborn son, Life Africa, was killed during a fight with police at MOVE headquarters.

1977: MOVE founded two offshoot groups: Seed of Wisdom in Richmond, Virginia, and a second group, composed mostly of fugitive MOVE people, in Rochester, New York.

1977 (May 20): An armed standoff between MOVE and the Philadelphia Police Department, called the Guns on the Porch standoff, ended peacefully.

1978 (March 16): The city of Philadephia began a blockade of MOVE headquarters in an attempt to “starve them out.”

1978 (August 8): Police officers raided MOVE headquarters, leading to an exchange of gunfire between MOVE and the police. Officer James Ramp was killed.

1980: The MOVE 9 were convicted for the murder of James Ramp. They were sentenced to between thirty and 100 years in prison.

1981: The ATF and the Rochester Police Department raided the MOVE community in Rochester, New York. All MOVE people in Rochester, including John Africa, were taken into custody.

1981: John Africa was acquitted on federal weapons and conspiracy charges.

1985 (May 13): Members of the Philadelphia Police Department and Fire Department, working in concert with federal law enforcement, attacked MOVE headquarters with guns, tear gas, and bombs, killing nine MOVE people.

2020: All living members of the MOVE 9 were paroled from prison.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Vincent Leaphart, the man who would become John Africa, [Image at right] was born in West Philadelphia on July 26, 1931 to a large, working-class African American family that had recently migrated north from Georgia. After completing the fifth grade, Vincent was diagnosed as being “orthogenically backward.” a racist, pseudoscientific diagnosis that caused a great deal of shame for Vincent and his siblings and that required Vincent to attend a different school. Vincent Leaphart was unusually intelligent, but he struggled to read and write throughout his life. If he had been diagnosed today, he might have been diagnosed with a learning disability, rather than an intellectual disability. As it was, Vincent dropped out of school when he turned sixteen, having completed only the fifth grade.

In 1952, when he was twenty, Vincent Leaphart was drafted into the United States Army and sent to fight in Korea. He was an infantryman and served on the frontlines in the last year of the war. He received an honorable release from active duty in October 1954, having served his full two-year commitment. After his discharge from the Army, Vincent spent the next decade splitting time between Philadelphia, Atlantic City, and New York, wherever he could find work. In 1961, Vincent Leaphart was living in Atlantic City, and he met and married Dorothy Clark. Vincent and Dorothy’s marriage was rocky and, at times, violent. They could not have children, which was a great disappointment to them both. The couple moved back to Philadelphia in the mid-1960s. Around that time, Dorothy began following the teachings of The Kingdom of Yahweh, a new religious movement combining Seventy-Day Adventism and British Israelism, founded by Reverend Joseph Jeffers in 1935. A year after converting to The Kingdom of Yahweh, Dorothy Clark filed assault charges against Vincent Leaphart. Before prosecution could commence, she withdrew her complaint, telling police that the domestic violence “only happened twice.” Shortly thereafter, the couple separated permanently.

Around 1967, after the end of his marriage, Vincent Leaphart began to transform into John Africa. Vincent’s family and friends noticed that he had grown withdrawn, contemplative, and aloof. He spent almost all of his free time holed up in an apartment in West Philadelphia developing the ideas that would go into a book manuscript called The Guidelines of John Africa.

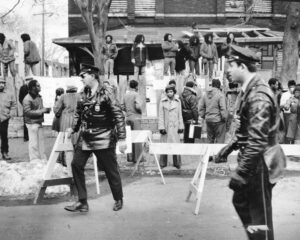

In 1972, a group of college students studying at the Community College of Philadelphia began discussing The Guidelines of John Africa as a part of their sociology course. When the semester ended in December of 1972, a handful of the students in this course continued meeting. Some of these meetings took place in John Africa’s apartment. His sisters brought their families with them to the meetings. His sister Laverne Sims brought her five children with her: sixteen-year-old Debbie, fourteen-year-old Gail, twelve-year-old Chuckie, and her two youngest, Sharon and Dennis. Laverne and all five of her children would eventually convert to MOVE and build their lives in the religion. Jerry Ford, who had been a student in the college class, converted to MOVE and became Jerry Africa. He joined Delbert Africa (who began following John Africa before the college course began), Laverne Sims, Louise James, Muriel Austin, Merle Austin, Don Grossman, and John Africa’s seven nieces and nephews to form the earliest core of MOVE. Together, MOVE people bought a house in the Powelton Village neighborhood of West Philadelphia. That house, 309 North 33rd Street, served as MOVE headquarters and was called The House that John Africa Built. MOVE people transformed the house into a sacred domestic space for their religion. Some MOVE people lived in the house. Others  slept elsewhere but spent most of their time at MOVE headquarters. MOVE’s large and growing population of dogs, which probably numbered two to three dozen, lived in one half of the duplex. MOVE people [Image at right] lived, worked, and worshipped in the other.

slept elsewhere but spent most of their time at MOVE headquarters. MOVE’s large and growing population of dogs, which probably numbered two to three dozen, lived in one half of the duplex. MOVE people [Image at right] lived, worked, and worshipped in the other.

MOVE people turned MOVE headquarters into a sacred space set apart from the fallen System. They dug up the concrete sidewalk in front of their home in order to allow plants to regrow. They eschewed technology and formal education both for themselves and the children born into MOVE. The group adopted John Africa’s ascetic lifestyle. On a typical day, MOVE people woke before dawn, boarded a bus, and drove to a nearby park where they ran and lifted weights. They returned home to run the dogs, then began the day’s work. In these early days, MOVE people concentrated on spreading John Africa’s message to the local community. They offered classes on John Africa’s teachings twice a week, which were open to the public. They rehabbed drug addicts, encouraged young people to reject gang violence, and helped their unemployed neighbors meet their rent. In these early years, MOVE people were, in the opinion of many of their neighbors, a helpful presence in the neighborhood.

MOVE’s trouble began when they began engaging in nonviolent direct action against activist groups. From 1973 to 1976, MOVE people demonstrated against hundreds of public events. They protested both liberal and conservative groups. They hurled obscenities at everyone from Jane Fonda to a group of high school students calling for President Nixon’s impeachment. They disrupted the gatherings of other religions, including Buddhists, Quakers, and the Nation of Islam, often in an attempt to debate theology. MOVE people even protested civil rights activists. In 1973 alone, they protested Cesar Chavez, nutritionist Adelle Davis, Jesse Jackson, Daniel Ellsberg, socialists, communists, the Philadelphia Board of Education, the American Indian Movement, Richie Havens, and many more. MOVE’s overarching complaint against these disparate groups was that they sought to remake the world from within the System, whereas John Africa taught that such reform was impossible. In response, the Philadelphia Police Department began arresting MOVE people with unusual frequency. MOVE people estimated that, in the mid 1970s, police arrested on average one MOVE person per day.

A major turning point in MOVE’s history was the death of a MOVE infant, Life Africa. In the predawn hours of March 28, 1976, a group of MOVE people who had recently been released from jail arrived at MOVE headquarters. MOVE people inside came outside to welcome them home. Within moments, police officers arrived, explaining that they had received noise complaints. According to MOVE accounts, a police officer struck fifteen-year-old Chuckie Africa on the head with a baton, causing a fight between MOVE and several police officers. By the time the fight was over, MOVE people were left bloodied and bruised, and six MOVE men were arrested. As the paddy wagons drove away, the MOVE people who had not been arrested realized that Janine Africa was missing. They soon found her sobbing in the basement, holding her newborn son, Life Africa, his skull caved in. She had been holding him as she tried to stop a police officer from striking her husband, Phil Africa. The police officer hit Janine instead, knocking her down. Life Africa had been crushed to death.

The death of Life Africa set into motion a chain of events that led, ultimately, to the MOVE Bombing nine years later. Convinced that the System was actively trying to destroy the group to suppress the Teachings of John Africa, MOVE abandoned their commitment to nonviolent resistance and embraced a doctrine of armed self-defense. They announced this change publicly on May 20, 1977, with a symbolic show of force. After another arrest of a MOVE person, other MOVE people stood on the front porch of MOVE headquarters brandishing firearms. This event, which the press dubbed the Guns on the Porch standoff, announced MOVE’s new doctrine of armed self-defense. In response, the Philadelphia Police Department stationed an around-the-clock observation squad, ranging between twenty and fifty officers, outside MOVE headquarters. They had orders to arrest any MOVE person caught leaving the house even though, years later, police admitted that MOVE people had not broken any laws during the Guns on the Porch standoff.

On February 21, 1978, eight months after the standoff began, the City of Philadelphia offered MOVE a deal to remove the observation squad and end the threat of arrest if MOVE people agreed to leave MOVE headquarters and relocate at least two miles  away. MOVE rejected the offer because they believed the city was not negotiating in good faith. In response, the mayor of Philadelphia, Frank Rizzo, ordered the Philadelphia Police Department to expand its observation squad into a full blockade [Image at right] of MOVE headquarters. Promising that “even a fly won’t be able to get in,” Rizzo ordered the water to the house to be shut off and for all food or supplies intended for MOVE to be confiscated by police.

away. MOVE rejected the offer because they believed the city was not negotiating in good faith. In response, the mayor of Philadelphia, Frank Rizzo, ordered the Philadelphia Police Department to expand its observation squad into a full blockade [Image at right] of MOVE headquarters. Promising that “even a fly won’t be able to get in,” Rizzo ordered the water to the house to be shut off and for all food or supplies intended for MOVE to be confiscated by police.

The city’s starvation blockade of MOVE headquarters ended on August 8, 1978. Mayor Rizzo, frustrated by his inability to force MOVE out of their house and increasingly concerned about the ballooning costs of the blockade, vowed to end the standoff. He had announced plans for the Philadelphia Police Department to raid the MOVE house and arrest everyone inside. He warned that if anyone resisted arrest, they would be “put down with legal force.” On the morning of August 8, bulldozers began destroying MOVE’s reinforced porch to allow fire department water cannons to flood the house. When MOVE did not respond, shooting began. (There is some debate over who shot first.) When the shooting ended, Officer James Ramp, a twenty-three year veteran of the Philadelphia Police Department’s Stakeout Unit, had been shot and killed. By 8:30 that morning, all of the MOVE people in the house (eleven adults and six children) had surrendered to police. Reporters watched as four Philadelphia police officers attacked Delbert Africa as he attempted to surrender. Photographs captured police officers beating Delbert in the head with the crown of a police helmet.

MOVE splintered after the shootout with police. Nine MOVE people were charged, collectively, with the murder of Officer James Ramp, and were each sentenced to between thirty and 100 hundred years in prison. They became known as the MOVE 9. John Africa led a second group of MOVE people (now fugitives from the law) to Rochester, New York, where they adopted new identities and hid out from police. A third group of MOVE people, mostly women and children, moved to Richmond, Virginia to begin a new MOVE chapter called Seed of Wisdom. Law enforcement eventually put an end to both MOVE offshoots.

On May 13, 1981, a team of sixty federal agents from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) raided the MOVE community in Rochester, arresting all nine MOVE people there, including John Africa. The ATF alleged that John Africa had planned to plant explosives in government buildings around the country. He chose to represent himself during his federal trial, which was called United States v. Leaphart and Robbins. The government’s case rested on the testimony of an undercover informant, Donald Glassey, whose testimony was confusing and, at times, contradictory. John Africa’s defense ignored the details of the allegation, which he considered to be obviously fabricated, and emphasized instead his miraculous abilities. The jury was not convinced by the government’s case and acquitted John Africa on all charges.

After his acquittal, John Africa returned to West Philadelphia, gathered what remained of his followers, and established a new MOVE headquarters in a home owned by his sister, Louise James, herself a MOVE person. For a couple of years, MOVE avoided further direct confrontations. They spent most of their time lobbying for the release of the MOVE 9. But by the Summer of 1984, both federal and local law enforcement had determined to put an end to MOVE’s presence in the neighborhood. On May 30, 1984, representatives from the PPD, the FBI, the Secret Service, the United States Justice Department, the District Attorney’s Office, the Mayor’s office, and the State Police Commissioner met to discuss legal grounds for raiding MOVE headquarters. They found none. The secret Service had investigated MOVE’s threats against President Reagan and found them to be too vague to prosecute. Neither the FBI nor the Justice Department could think of a justifiable reason to storm the house or to remove the children. There were no outstanding state or federal warrants.

Despite having no legal reason to raid the house, after that meeting, Police Commissioner Gregor Sambor began drawing up plans for an offensive against the occupants of the MOVE house on Osage Avenue. The plan was for a large, early-morning raid that would catch MOVE people by surprise. Like they had done in 1978, Fire Department personnel would use deluge guns to blow open the windows and flood the house. Unlike 1978, the police planned to use bombs to blow holes in the walls and the roof of MOVE headquarters. They hoped the holes would allow them to fill the house with tear gas. If the water and the tear gas did not flush MOVE out, another bomb would be used to blow off the front door, allowing a seven-man assault team to storm the house. If MOVE tried to escape out the back, they would be met by another assault team. Four stakeout units (snipers, presumably) would be stationed on the roofs of nearby houses.

The Philadelphia Police Department put their plan into action for the first time on August 8, 1984. Three hundred police officers and firefighters surrounded MOVE headquarters. They brought with them fifteen paddy wagons, two armored cars, the bomb squad, and several firetrucks and ambulances. Most of the neighbors had evacuated the night before, per police orders. The police officers manned their guns and waited, but nothing ever happened. Without a legal reason to raid the house, the police depended on MOVE beginning a confrontation. But MOVE refused to take the bait, and City Manager Leo Brooks called off the attack.

The Philadelphia Police Department rescheduled the raid for May 13, 1985. That morning, the Philadelphia Police Department, using military grade firearms and explosives they borrowed from the FBI, raided the MOVE house on Osage Avenue, ostensibly to serve arrest warrants on four MOVE people inside. MOVE people inside the house fired at police. The police responded by firing over 10,000 rounds of ammunition into the house over the course of ninety minutes. They used explosives to blow holes into the walls, which they used to fill the MOVE house with tear gas. One of those bombs killed John Africa. The Fire Department used water cannons to flood the basement. These tactics did not force the surrender of MOVE people inside, and several hours passed without any confrontation as the MOVE children sheltered in the flooded garage and Frank, Raymond, and John Africa lay dead upstairs. At around five in the afternoon, a member of the Philadelphia Police Department’s Bomb Disposal Unit, using a Commonwealth of Pennsylvania helicopter, dropped a bundle of highly flammable C-4 explosives and Tovex onto the roof of the MOVE house. The decision to drop a bomb on the house was not improvised, as the police would later claim, but had been planned for over a year. The bomb created a massive explosion and fire, which officials decided to let burn to their tactical advantage. The fire forced the surviving MOVE people (four adults and six children) to flee the basement into the back  alleyway. Once outside, members of the Philadelphia Police Department opened fire, shooting Conrad Africa and Tomaso Africa, and forcing the others back into the flames, where all but two died. The fire continued to rage uncontrolled, and burned the entire city block, [Image at right] destroying sixty-two homes.

alleyway. Once outside, members of the Philadelphia Police Department opened fire, shooting Conrad Africa and Tomaso Africa, and forcing the others back into the flames, where all but two died. The fire continued to rage uncontrolled, and burned the entire city block, [Image at right] destroying sixty-two homes.

A full forensic investigation took weeks but, when the dust settled, investigators found the remains of eleven MOVE people. John Africa had died early in the day, probably from a bomb blast. Examiners were unable to provide a positive identification, as only a burnt torso had been recovered. Frank Africa and Raymond Africa died either from the same bomb that killed John Africa or from police gunfire shortly thereafter. There was no smoke or ash in the remains of their lungs, indicating that they were dead before the fire. Conrad Africa, Rhonda Africa, and Theresa Africa died sometime after the final bomb, either from gunshot wounds, smoke inhalation, or the flames. The children (Sue Africa’s nine-year-old son Tomaso, Conseualla Africa’s two daughters Zanetta and Tree, thirteen and fourteen, Janine and Phil Africa’s ten-year-old son Phil, and Delbert and Janet Africa’s twelve-year-old daughter Delisha) died in the basement. Remains from one of the children (examiners were unable to determine who, though it was likely Tomaso) contained buckshot pellets from a police shotgun.

After the bombing, Mayor Wilson Goode appointed a group of prominent community members, including clergy, political leaders, lawyers, and activists, to launch an investigation into the city’s handling of the MOVE crisis. The investigation lasted for months and proceedings were broadcast live over television and radio. The MOVE Commission, as this group was called, determined that by the early 1980s MOVE “had evolved into an authoritarian, violence-threatening cult” which was “armed and dangerous,” and capable of “terror.” But the MOVE Commission also agreed that the mayor, the city manager, and the police commissioner had been “grossly negligent and clearly risked the lives of the children” and that the city’s actions were “excessive and unreasonable.” The commission called the plan to drop the bomb “reckless, ill-conceived and hastily approved.” They also accused the Philadelphia Police Department of shooting at MOVE children as they attempted to flee the fire, forcing them to retreat back inside the burning house. Because of this, the MOVE Commission concluded that the deaths of the five MOVE children were “unjustified homicides which should be investigated by a grand jury.” In the end, however, the only person criminally charged after the MOVE Bombing was Ramona Africa, the only adult to escape the MOVE Bombing alive. Ramona was taken into police custody after escaping the fire and was taken to a hospital. She suffered severe burns from the fire, the scars from which she bore through her life. She refused medical treatment, citing her religious beliefs, and was taken to jail. She faced nine charges: three counts of aggravated assault, three counts of recklessly endangering another person, inciting a riot, conspiracy, and resisting arrest. Ramona Africa was convicted and served seven years in prison.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

John Africa began composing MOVE’s sacred text, which would become known as The Guidelines of John Africa, in the fall of 1968. John Africa dictated The Guidelines over a span of six years. Several people helped him create the manuscript. They describe the process similarly. John Africa would sit in a chair or on the floor and begin speaking. A second person, originally family members and, later, disciples, would type his words into a typewriter, struggling to keep up with his stream of revelation. John Africa instructed his assistants to type in all capital letters and not to use any periods. Occasionally he would pause, not to gather himself or to think about what to say next, but to give the typist a moment to catch up. Then he simply picked up right where he left off.

By the late 1970s, MOVE people divided the manuscript into sections, and arranged John Africa’s teaching topically. The oldest sections of the manuscript contain John Africa’s teachings on economics, gang prevention, and government. Over time, The Guidelines grew to include sections on a host of topics, including gender, sex, diet, death, entertainment, animal welfare, marriage and divorce, childrearing, and abortion. By 1974, MOVE people revered the text as scripture, often referring to The Guildelines as “MOVE’s bible.” MOVE people also believed that the teachings contained in that text had the supernatural ability to affect the “body chemistry” of those who heard it spoken.

Overall, The Guidelines of John Africa provide an explanation for, and solution to, the problem of evil. John Africa called forces of evil the “reformed world system,” or, more frequently, “The System,” borrowing a phrase that New Left radicals made popular in the 1960s to describe capitalism, political corruption, and the emerging neoliberal order. John Africa had these things in mind when he wrote about the System, but he meant much more than that. To him, the System was fundamental to the cognitive process. Humans, unlike any other animal, have the ability to think critically about themselves and to view themselves abstractly. The ability to think abstractly made humankind dissatisfied with the natural order of Life. Animals do not feel this dissatisfaction with the world. They act on instinct, fulfilling their natural impulses. And this, according to John Africa, is what puts animals in touch with the divine. Humans grew proud of their minds and their abilities to comprehend and influence their surroundings. But consciousness backfired. Humans created concepts, ideas, systems, order, logic, numbers, all categories of thought that further abstracted them from the natural order of life. These second-order concepts, all born out of the mind of humankind, alienate us from what John Africa called the “common expression of [the] absolute.” The uniquely human experience of living in alienation from Life is what he meant by “the System.”

In his religious thought, the System was an active, kinetic force. It had to be counteracted. It held the world captive, but it could be escaped. And once MOVE people were outside of the System, they could work to bring it down. In practice, MOVE people sought to counteract the damage the System had wrought. What this practice looked like changed over time, but in the group’s first few years, MOVE believed that pointing out the contradictions and hypocrisies inherent in the System would open people’s eyes to the evils of the world and force the System to implode. John Africa borrowed this idea, in a roundabout way, from Hegel and Marx.

His theodicy of the System has obvious parallels with the Christian theodicy of the Fall. John Africa was raised in the Black Church, so he would have been most familiar with some variation of Augustinian theodicy. In this reading of the Book of Genesis, humankind was created to commune with God and live in perfect harmony with the natural world. But humans rebelled, trading this perfect existence for the knowledge of good and evil. The consequences of this rebellion include death, shame, and sin. John Africa carried the Eden narrative to its logical extreme. Adam and Eve learned something they should not have learned, so if forbidden knowledge led to humankind’s fall from an Edenic existence, the wholesale rejection of systems of human comprehension would return humankind to paradise. Like some readings of the Fall, the story of the origin of the System is one that does not exist in time. It is both primordial and ever-present: past, present, and future. The System emerged when humankind first began cooking food. It emerged when humankind sought to replicate the flight of birds through aircraft. And it continues to emerge when scientists genetically modify food. The System, in MOVE belief, is constantly evolving, constantly being reinvented, and is self-perpetuating.

Although the System was, in many ways, a repackaging of the Fall, the way John Africa articulated his theodicy and his offer of redemption was firmly rooted in the religious and political currents of the late 1960s. The construction of the System was, for humankind, a self-imposed exile from the natural world because the second-order constructs that humans developed to comprehend and categorize the world “alienated” humankind from the natural order of life. Alienation was in the air when John Africa developed this theodicy in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Some in the baby boomer generation (the generation from which MOVE’s core emerged) developed a “post-scarcity” radicalism. This was a politics that focused on culture, social, and political alienation rather than on issues of economic inequality that had concerned previous generations. Across the country, in organizations ranging from the YMCA to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, from the Students for a Democratic Society to the Black Panthers, the generation that came of age in the 1960s developed a religious and political radicalism based upon the language of Christian existentialists such at Kierkegaard, Tillich, and Bonhoeffer. To them, the key to escaping alienation was to live lives of “authenticity.” Certainly, John Africa was not reading in Christian existentialism, but he was undoubtedly engaging with these ideas in other forms. Christian existentialism was in the zeitgeist of late 1960s. Indeed, as John Africa’s neighborhood in West Philadelphia transformed into a hotbed of New Left radicalism with the expansion of the nearby universities, existentialism was the zeitgeist, even if the concepts were presented in secular forms. It should come as no surprise, then, that authenticity was precisely what the Teachings of John Africa offered. He called MOVE “the most organized body to ever wear the title of human with total comprehension.”

Although the System was the product of humankind, it had agency apart from the actions of humans. It was a supernatural force as well as a human one. In John Africa’s thought, because people are naturally opposed to the System (perfect in essence), they are “allergic” to it. In a section of The Guidelines written in May 1967, He explained that:

“everybody’s allergic to violation and when you violate you can expect to suffer, when you got a pain in your head you got an allergy, when you got a pain in your chest you got an allergy . . . anytime your own heart attacks you, you know you ain’t doing right . . . ain’t nothing common ’bout a cold, a virus ain’t nothin’ but a term devised by science to describe unfamiliar ailments they ain’t got around to so-called accurately describin’ yet.”

Humans’ allergy to the System manifests as illness, injury, and addiction. The allergies could be overcome, he taught, by dietary and exercise adjustments and by under-standing the illusory nature of illness. He wrote:

“you ain’t allergic to eatin’, you ain’t allergic to sleepin’ or drinkin’, you are allergic to the attempted application of this reformed System that ain’t nobody been able to digest, accept, engage with.”

John Africa taught that addictions arose from the alienation people intuitively felt within the System. Addictions, like illnesses, could be overcome once the sufferers realize that their affliction is only an illusion caused by a supernatural, evil force.

The System, powerful though it was, is not the only force at work in John Africa’s cosmos. His worldview was dualistic; it understood the cosmos as a site of conflict that pitted forces of good against forces of evil. The force of good went by many names: the Law of Mama, the Law of Nature, God, Natural Law, and most frequently, Life. Natural processes, according to MOVE, are “coordinated” by this active force. When we experience thirst, that is Life telling us to drink water. When we experience tiredness, that is Life telling us to sleep. This, to MOVE, is God. The life God desires for human beings (indeed, for all living things) could not be more apparent. God wants nothing more than for humans to eat, sleep, reproduce, and die. As he wrote in The Guidelines, “. . . the total application of this principle should be crystal clear, you must eat, you must sleep, you must drink, this is the common expression of life, the instinctual Law of Mama that all must adhere to. . . .” The degree to which people live their lives in accordance to this natural state (the Law of Mama) is the degree to which they live a fulfilling life according to God’s will. Indeed, living in perfect accord with Natural Law (something that is possible and has been performed by at least two human beings) is the degree to which we are God.

According to The Guidelines, there was one other person besides John Africa who lived in total harmony with Natural Law, Jesus of Nazareth. John Africa had deep respect for Jesus and saw him as a forerunner for his own message. He called Jesus “the god of self, lord of reality, omniscient of wisdom.” “Look at this man,” The Guidelines state, “and see the god, truth that he is, the god that you must be if you too are to become a Christ.” “In looking at god, at Jesus, at self you need look no further, for you are seeing the truth, the comprehensiveness of reality, the cultural manifestation of self, the life and breath of nature, of god, of all.” To him, Jesus can rightfully be called God, not because he is a supernatural being, but because he was a man who lived life in perfect accord with Nature. Christians are to blame for “intermixing Jesus with their mythical god, making it appear that they are one and the same.” Jesus is not God because he was all powerful. Jesus is God because he lived a human life in total conformity with the Law of Mama.

The Guidelines of John Africa teach that God that is both transcendent (existing apart from matter) and thoroughly immanent in creation. John Africa’s God is not a personal being. The God of The Guidelines is a creative, omnipresent, feminine (“only a woman can give birth, produce life”) force. He taught that “man has for so long been crippled with the idea of god as a separate force, a separate power, something that is supernatural, Guidelines not of this world.” They teach that the world’s religions erred in imagining God as a superhuman person deity that exists apart from the created world, a mistake John Africa called the “synthetic god” of human imagination.

He presented a conception of the divine that could be, for the sake of comparison, classified as a kind of panentheism. Whereas pantheism is a conception of the divine (often associated with Ancient Greece) that God exists in the natural world as an “animistic force,” panentheism posits that God is both immanent and transcendent. To John Africa, the natural world was not God, but it was God’s revelation. The immanent and the transcendent are effectively the same. God was the “animinstic force” blowing the wind, churning the tides, and germinating the seeds, but God was also separate from the created world. God could intervene in natural forces if she wished, she could speak through her prophets, and she could exact justice and revenge. This is why the passage speaks of God’s “power” as being “common as dirt,” but also speaks of a road that leads to God. The dirt (the natural world) is the medium through which God manifests her agency. But the passage also makes clear that God is immanent in matter: “Don’t tell me my Momma ain’t just in Her wisdom.” Of course, no theology is static, and MOVE’s conception of God evolved over time. From the early 1980s through his death in 1985, John Africa became a divinity, himself. But MOVE consistently disavowed a conception of the divine that was exclusively transcendent and spirit.

John Africa’s conception of God grows from a broader rejection of what he called “the folly of mythology.” Like many African American and African-derived religions, MOVE rejects some aspects of supernaturalism. John Africa argued against the belief that spirit, God, and the soul are “some kind of supernatural, transparent mass of nothingness floating around in space.” The Guidelines insist that otherworldliness of other religions is a misreading of the Bible and a sacrilege toward the natural world. Though there are deep connections between his theology and the humanist tradition within African American religious thought, MOVE’s theology does not neatly fit the category. The Guidelines of John Africa do not present a wholesale rejection of supernaturalism, but, rather, an elevation of the natural to the sacred.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

John Africa taught that it was possible to escape the System through a set of religious practices; both those found in The Guidelines of John Africa and in those modeled by John Africa himself. To him, in order to escape the System one must first learn how to unlearn; that is, one must first ground abstracted theoretical concepts into everyday, lived reality. A useful tool for this process of unlearning was the body. To him, the body was the crucial site at which abstract, intangible theological concepts translated into the mundane and the site at which the cosmic conflict between good and evil was fought. He wrote:

our religion is our body, it is our eyes, our ears, our feelings, our union, our lungs, our limbs our blood rich with life, of family, of firmly engaging commitment, all things thats [sic] immediate and cannot be argued, cannot be amended, conceded or promised, or auctioned or swapped or given away, for as the body is the lung, limb, the eye, the vein to engagement, it is the heart-beat to pump the blood of connection, and as there is no fiber of the body that is not of the body, there is nothing for MOVE to concede or negotiate without giving away the necessity of life, an arm, a leg, an eye, a lung, all things of completion when you are together, the love of true family, the peace that trust brings, the freedom that only exists when you’re faithful, the body that MOVE is committed to be, without hesitation, for this is our breath, as certainty is the real strength of true law, the order that powers the way of together.

To free his followers from the effects of the System, John Africa made the body a site of discipline. For him, the body was, in its natural and un-polluted form, perfect. But like everything held victim to the System, the body was polluted, even the bodies of MOVE people. MOVE people strove for perfection, for total purity of their material selves, but they knew they could never achieve it. What was important, to John Africa, was that MOVE people believed they could perfect their bodies and pursued perfection in principle. In The Guidelines, he wrote, “. . . until you learn to believe in perfection, accept the meanin’ of totality, realize the common expression of ab- solute, you will be hungry for truth, for justice, sufferin’ from shortness of breath, cryin’ for the only liquid of perfection what will quench the historical thirst of reformed inadequacy. . . .” MOVE people believed in perfection and pursued it. Only he, who was supernaturally gifted, and the MOVE children, who were born outside of the System and thus exempt from its domination, were capable of living a life in perfect accord with Mama. The rest could not reach perfection, but they were expected to try through strict bodily discipline.

Living a life in perfect harmony with Mama could be pursued through a restrictive religious diet. MOVE people followed what today might be called a raw, whole-foods diet. Usually, they ate vegetables, grains, nuts, fruits, roots, raw eggs, and, rarely, raw poultry and meats. By necessity, MOVE people cooked some foods, including rice, beans, and other foods that are inedible raw. Ideally, all foods should be wild, organic, uncut, unpeeled, and unprocessed in any way. According to MOVE belief, God provided food in the form that it should be eaten. If a food could be chewed and swallowed raw, God intended it to be eaten raw. It is humankind, in all of its vanity, that decided food should be cooked. Food and water which is unpolluted and unadulterated is most like God. Consuming this kind of food (and only this kind of food) placed MOVE people in communion with the divine.

The second way the Teachings of John Africa disciplined the body was through work. To MOVE people, hard work was a sacrament. To work hard was to be fully human, in touch with the divine. On a typical day, MOVE people woke before dawn, boarded a school bus they owned, and drove to Clark Park, a large open field ten minutes from the Powelton house. There, MOVE men, women, and children ran around the park for an hour or more. After the morning run, they returned home to walk their dogs. MOVE cared for dozens of dogs at any given time. Because their theology forbade them from having their dogs spayed or neutered, new litters were constant. After walking the dogs, MOVE sat down for breakfast. Then the day’s work began. MOVE people supported themselves through handyman services and by pooling their welfare checks. They also ran a carwash in front of the MOVE house, consisting of a garden hose and some buckets and sponges. On busy days, the car wash could bring in $300–$400 in donations. Much of the work was divided by gender, though this was less of an ideological prescription as it was a practical necessity. The men picked up odd jobs around the neighborhood and manned the car wash. The women were responsible for the unending work of preparing meals for the growing congregation. They bought fresh fruits and vegetables from the market daily. Because there was no electricity or gas much of the time, most of the meals were cooked outside over a barrel fire.

The Teachings of John Africa instructed MOVE people to guard against anything that alters the body’s natural chemistry. They were expected not to smoke or drink. Drugs of all kinds (including marijuana, prescription medication, and over-the-counter medicines) were strictly forbidden. He called these “violations of the body.” One of the most effective means of escaping the grips of the System was to eliminate all violations. In MOVE, violations included eating too much food, drinking too much water, and not sleeping enough. John Africa did not punish violations of the body; violations were not transgressions against him, but against Life. Life punishes violations. When someone drinks too much water, for example, they are punished with an urgent, painful need to urinate. When they drink too much, they suffer from hangovers. When they overeat, they suffer from intestinal discomfort. John Africa taught MOVE people to interpret some of their bodies’ signals (especially pain) as divine punishment for violating their bodies. He understood that, while striving toward perfection was necessary, MOVE people would inevitably fail. In MOVE, he instituted what he called “distortion days.” These were special occasions when MOVE people were encouraged to engage in some of the violations of which they were striving to rid themselves. Of course, many violations were unthinkable: there was no drug use or alcohol or promiscuous sex on distortion days. Instead, MOVE people might gorge on junk food and candy, watch television, or skip their daily exercise regimen. It was not as much of a day of licentiousness as it was a dieter’s cheat day.

John Africa encouraged his followers to adapt their bodies to a more natural lifestyle. All MOVE people wore their hair naturally, un-combed and uncut, a style that was controversial in the early 1970s, especially among middle-class and upwardly mobile African Americans, for whom respectability was the most promising way toward racial advancement. They dressed unfashionably. Both men and women wore unwashed sweatshirts, blue jeans, and work boots. Most alarming to MOVE’s critics, MOVE people did not take baths, except for the occasional dip in the creek. They did not use soap or personal hygiene products. Instead, they occasionally rubbed their bodies with a mash of garlic and herbs. The smell, too, was a way for MOVE people to mark themselves as a separate people and to reclaim their bodies from the System. The Teachings of John Africa oriented the body away from the System and toward the divine. MOVE people’s clothing, hygiene, and grooming choices were a way of setting themselves apart as a religious community. But opting into MOVE was, in effect, opting out of the System. The lifestyle the System demanded (working a job, dating non-MOVE people, even driving a car) was rendered much more difficult after the physical changes MOVE people underwent. But MOVE people found orienting their bodies toward nature to be transformative, physically and spiritually. The Teachings of John Africa gave MOVE people a way of understanding their bodies in relation to the divine, of mapping the communal onto the corporeal, and of establishing the boundaries of their peoplehood. MOVE people’s bodies became religiously formed bodies, positioned in relation to the Teachings of John Africa.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Until his death in 1985, John Africa was MOVE’s undisputed leader, though in terms of doctrine, MOVE has no leadership or hierarchy. He spoke with the authority of the divine. He was called MOVE’s “Coordinator” (a phrase that in The Guidelines refers to God), and MOVE people trusted his guidance implicitly. Ramona Africa, the sole adult survivor of the MOVE Bombing, took over the leadership of the MOVE after she was released from prison in 1997. Within the last couple of years, a new generation has begun to take charge of MOVE. Today, Mike Africa, Jr., son of Mike Africa and Debbie Africa, represents MOVE publicly.

Since around 1976, MOVE has not actively sought new members. It is, in many respects, a closed religion, though a handful of people have joined MOVE over the years. Today, there are probably less than one hundred MOVE members, though MOVE people decline to provide an exact number. Most MOVE people today were born into the religion. They use two categories of belonging. The phrase “MOVE member” refers to those people who follow the Teachings of John Africa exclusively and who other MOVE people accept as a member of the MOVE family. The second category, MOVE supporter, is much more capacious and includes thousands of people around the world who draw inspiration from the Teachings of John Africa and support MOVE’s political and activists causes.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

MOVE has faced two primary challenges throughout its history: the question of how MOVE should be classified and the question of how the MOVE Bombing should be remembered.

MOVE people believed, from the very early days of the group, that their leader, John Africa, was a prophet, that his teachings (both written and embodied) had miraculous effects on the body, and that the shared beliefs and practices that constituted MOVE were religious in nature. To MOVE people, Vincent Leaphart was John Africa, a prophetic figure who was capable of performing miracles, healing the sick and injured, and communicating on behalf of the divine. John Africa inspired a remarkable level of devotion in his followers, who called themselves his “disciples.” He was, according to one MOVE person who was interviewed after she left the group, “like a messiah.” When asked to compare John Africa to Jesus, another MOVE person scoffed, “Jesus Christ—who is he? We’re talking about John Africa, a person who is a supreme being, who will never die and will live on forever.” MOVE people, to this day, proclaim John Africa as “a religious symbol and a person who is better than anyone else in the world and better than anyone who has ever lived up to the present time.” The Teachings of John Africa were the exclusive truth, the path to redemption, and the ultimate reality. MOVE, to those inside the group, was a religion.

To many people outside the group (including the police, the court system, MOVE’s neighbors, and other religious groups), MOVE was anything but a religion. A Quaker group classified MOVE as “a street gang with a thin veneer of politico-religious philosophy.” A group of MOVE’s neighbors who were hostile toward MOVE’s presence in the neighborhood considered MOVE an “armed terrorist” organization. A lawyer representing Birdie Africa rejected the premise that his client was a former “MOVE member” on the basis that the label presupposes that a child can belong to a political group. In the lawyer’s estimation, Birdie “was no more a member of MOVE than a child of Republican or Democratic parents would be styled by a particular party label.” A judge asked to decide whether MOVE was a religion concluded that MOVE was “independent of religion and with separate and distinct purposes.” Even liberal religious groups sympathetic to MOVE preferred to understand MOVE in political terms, calling them a “revolutionary organization that advocates a return to nature and spurns all social conventions.” At almost every turn, MOVE, a group that was desperate to be recognized as a religion, found themselves categorized as secular. As one MOVE person put it, “they just spit all over our religion like our religion didn’t count.”

The second challenge facing MOVE has to do with historical memory. MOVE’s history is the source of a great deal of pain, both for MOVE people and people outside of MOVE. There are many people who believe that this is MOVE’s fault. Chief among their complaints is that MOVE is responsible (either directly or indirectly) for the death of Officer James Ramp. (MOVE people, it should be noted, deny any responsibility for the death of Officer James Ramp.) To many of their critics, MOVE people are cop killers. But the criticisms of MOVE have always been broader than this. MOVE’s critics have found them to be obnoxious, even hateful, toward people with whom they disagree. Critics often point out MOVE’s hypocrisy. Nearly every article or book written about MOVE points out that John Africa would go out of his way to avoid stepping on a bug but had no problem shooting at police officers. These critics wonder, not unfairly, how MOVE claims to respect the sanctity of life while behaving so violently.

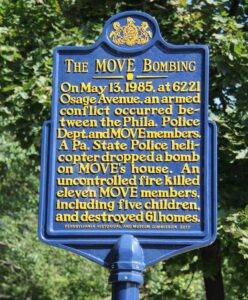

These issues inform the question of how the MOVE Bombing should be remembered. For many years, the MOVE Bombing was mostly forgotten outside of Philadelphia. That is beginning to change. In 2017, the City of Philadelphia erected a historical marker [Image at right] at the site of the MOVE Bombing. It reads:

On May 13, 1985, at 6221 Osage Avenue, an armed conflict occurred between the Phila. Police Dept. and MOVE members. A Pa. State Police helicopter dropped a bomb on MOVE’s house. An uncontrolled fire killed eleven MOVE members, including five children, and destroyed 61 homes.

The historical marker relies heavily on passive voice to avoid assigning blame for the MOVE Bombing, but its mere existence is evidence that the City of Philadelphia has begun to confront this painful chapter in its history.

IMAGES

Image #1: John Africa.

Image #2: Group photo of MOVE people.

Image #3: Philadelphia police blockade of MOVE headquarters.

Image #4: Photograph of MOVE bombing damage.

Image #5: Move bombing historical marker.

REFERENCES**

** Material in this profile is drawn from Richard Kent Evans, MOVE: An American Religion. (Oxford University Press, 2020) unless otherwise noted.

Publication Date:

13 May 2020