ZAR SPIRIT POSSESSION MOVEMENT TIMELINE

Date unknown: Zar belief and possession originated in eastern and central Africa.

Fifteenth century c.e.: The conversion of the newly established Funj kingdom to Islam took place, and Sufi beliefs and practices spread throughout the central Nile area.

1839: The earliest recorded accounts of zar rituals were recorded from Ethiopia by Christian missionaries.

1880: Zainab bit Buggi, later known as Grandmother Zainab (Haboba Zainab), was born in Omdurman, Sudan. Shortly afterwards she was taken north to Egypt.

1883–1897: Oral accounts of zar possession survive from the Mahdist state in Sudan.

1896–1898: Zainab returned to Sudan with the Anglo-Egyptian army and a soldier named Mursal Muhammad Ali.

1898–1955: There was Condominium (Anglo-Egyptian) rule in Sudan.

1905: Zainab and Mursal were sent as colonists to Makwar, a village on the Blue Nile River.

1910: After the death of Mursal, Zainab remarried and moved with her children to a village near Sinja. Her new husband, Marajan Arabi, was a powerful leader in zar.

1930: Widowed again, Zainab returned to Makwar/Sennar to live with her oldest son Muhammad. Together they built up a thriving house of zar. There Zainab trained the next generation of zar burei practitioners, at a time when zar beliefs and practices expanded rapidly.

Mid-twentieth century: More radical, Wahhabi-influenced Islamic beliefs arose in Sudan.

1956: The Sudanese gained independence from Britain.

1960: Grandmother (Haboba) Zainab died.

1983: Shari‘a law was imposed in Sudan.

1989: A military coup in Sudan led to the establishment of an Islamist state, led by President Omar al-Bashir.

1990s: Zar rituals were banned and zar leaders were persecuted.

2000: The ban against zar rituals was no longer actively enforced, and women continued to hold zar ceremonies in private locations.

2019: The Islamist regime was overthrown.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Spirit possession beliefs and practices known as zar (or sar) are widespread throughout northern Africa and the Middle East, from Morocco to Sudan and Ethiopia, to Iran, as well as throughout the world in the diasporic communities where many of those peoples now live They are practiced predominantly in Muslim, though also in Christian, Falasha, and animist, societies. While beliefs are widely shared by men and women, today’s practitioners and leaders are mainly women.

Zar beliefs and practices are believed to be very old in eastern and central Africa, but their origins and early history are now lost. The earliest known recorded account of zar activities comes from Ethiopia, dating back to 1839 (Natvig 1987). Missionaries J. L. Krapf and C. W. Isenberg left separate descriptions of a ritual in which a woman tried to appease her possessing spirit or sar. Many of the features they describe are still found in contemporary zar rituals. Later nineteenth-century accounts from Egypt (Klunzinger 1878) and Mecca (Hurgronje 1931) make clear that by that time, zar beliefs and rituals were widespread. Most researchers today agree that this spread of zar beliefs was tied to the ranks of the Ottoman armies in the nineteenth century, particularly to the activities of the slave troops and their dependents, from which they passed to the larger population. Much of today’s zar ritual and performance is derived from that time.

This account is based on field research from the Republic of Sudan (generally known simply as Sudan), where zar continues to be colorful and dynamic, even within the recent Islamist state (1989–2019). The influence of Islam, notably Sufi Islam, which has dominated this part of Africa for four centuries, is evident in both zar ritual and organization. For much of its history, zar has co-existed within the larger Islamic context. Zar has been particularly well described in Sudan (notably al-Nagar 1975; Boddy 1989; Constantinides 1972; Kenyon 2012; Lewis et al. 1991; Makris 2000; and Seligman 1914). There are oral accounts of zar in the Sudan since at least the late nineteenth century, reported in Constantinides (1972) and Kenyon (2012). During Mahdist rule (1883–1897), and probably earlier, women and men were collectively celebrating possession by particular spirits, known generically as the Red Wind, al-rih al-ahmar, or zar. The spirits themselves are also sometimes known as al-dastur, variously translated as “hinge” or “constitution,” suggesting an articulation of spirit and human worlds.

In the past, women recall that there were several different types of zar practiced in the Sudan: zar burei, zar tombura, and zar nugara, at the very least. Though their rituals differed, diverse origins posited for them and individual spirits varied, all were based on a similar understanding of the world of red spirits. Today only burei and tombura are found in Sudan, and in practice there is now a certain amount of overlap, collaboration, and shared history.

Today the term zar refers to several things. It is a particular type of spirit, and it also describes the condition of a person possessed by that spirit. It is a form of disorder caused by that possession, as well as the ritual associated with zar spirits, which can include drumming, singing, sacrifice, colorful representation of others, feasting, heady incenses, all coupled with unpredictability and tension. Occasionally men are found at zar ceremonies, and may claim to have expert understanding of the phenomenon. Often, however, they are viewed as homosexual by women at that event, who know that much of today’s zar ritual takes place away from male eyes; male participants are treated quite differently. This is essentially a women’s space.

The following case study from the town of Sennar, central Sudan, illustrates the type of history behind many independent zar burei groups in the country, reinforcing the connections between zar and the Ottoman army, as well as representing the fluctuations in spirit manifestations over time. It is unique only because the descendants of the founder of this group left a record about their group’s history (in Kenyon 2012). The founder, a woman still remembered as Zainab bit Buggi (daughter of Buggi) or Grandmother Zainab (Haboba Zainab) was born in Omdurman in about 1880, a time when this region was still an outpost of the Ottoman Empire. Few details of her early life have survived, but relatives recalled how when she was still young she was taken to Upper Egypt, where she was attached to the household of the Ababda nobleman, Agha Osman Murab. The timing of her departure from Omdurman as Ottoman authority collapsed, the name of her father (or “owner”), and her early life in the household of a man remembered as al-agha, an Ottoman military title, all reinforce the probability that she was born to a slave background, with links to the army. Zainab’s descendants later recalled how it was while she was still a young girl in Upper Egypt that she came to know the zar spirits, although there is no evidence that she was actively involved in its ritual at that time. References to this period “in the palaces” continue to be remembered vividly in zar ritual, brought to Sennar by Grandmother Zainab.

At some point, Zainab met a soldier named Mursal Muhammad Ali, an Egyptian of Sudanese (Dega) origin. With him she returned to Sudan, part of the Anglo-Egyptian invasion force of 1896–1898. At the battle of Karari, just north of Omdurman, this army defeated troops loyal to the Khalifa ‘Abdallahi. Ottoman authority was restored in the name of “Condominium” rule, whereby power was shared (at least nominally) by British (al-Khawajat) and Egyptian (al-Pashawat) officials.

Zainab and Mursal spent only a short time in Omdurman before moving two hundred miles south to a small colony on the Blue Nile River, Makwar, established to house retired soldiers and their families. Zainab settled down to the life of a farmer’s wife and soon afterwards, gave birth to twins, Muhammad and Asha. Mursal died a few years later, however, and Zainab subsequently married one Marajan Arabi, moving to his village near Sinja, eighty miles south of Makwar. Marajan was a well-known practitioner of zar nugara and, though nugara is no longer practiced in Sennar, his formidable powers are still recalled. Soon after the marriage, Zainab became ill. Marajan recognized that although she was ill with zar, it was not nugara. A leader of zar burei, al-Taniyya (also known as Halima), was called to treat her with a full seven-day ritual, and she recognized Zainab’s own powers in zar. Once Zainab recovered, she began training with al-Taniyya, learning to summon the spirits and negotiate with them.

This was to become the basis of zar burei in contemporary Sennar. Though present-day tombura in Sennar is unrelated, the tombura leader in 2001 recalled Zainab’s powers with respect:

Sennar zar today is just from Zainab. When we became aware we found she had it. . . . It was all from that woman called al-Taniyya, from the Turks, from mashaikha kabira (the senior female leader) (Kenyon 2012:51).

Meanwhile Zainab’s son Muhammad became an eager student of Marajan, exhibiting strong powers himself in nugara. He became a soldier, but on his retirement (around 1925) he returned to his own father’s home and allotments in Makwar/Sennar, where he soon established himself as a formidable zar leader. When Zainab was widowed for a second time (around 1930), she returned to live with Muhammad and his wife Sittena. Subsequently they practiced zar together in the courtyard of their home, right in the heart of the town, building up a large clientele in the area. The family prospered and their increasing wealth was later recalled with awe. Over the next three decades Zainab acquired a reputation as a formidable and compassionate leader. The women she trained became the next generation of zar leaders and today, all zar burei houses in Sennar claim descent from Grandmother Zainab.

Zainab died in 1960, but the period when she was practicing zar in Sennar (1930–1960) was a time when zar beliefs and practices mushroomed in Sudan (Constantinides 1991:92), largely ignored by or unknown to the Anglo-Egyptian authorities. In the later twentieth century, this trend continued, until the coup of 1989 led to the establishment of an Islamic state, under which zar was ruthlessly singled out for persecution.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Zar beliefs center on the existence of red spirits, a particular type of spirit that lives a parallel life to humans, and is distinguished from black spirits, the other major spirit category. The latter, sometimes known as djinn, inhabit dirty and hazardous spaces, and if they come into contact with a human body, might jump and possess it, invariably causing problems, including sickness, and even madness. Such dangerous spirits must be exorcised before the host can recover, a challenge only performed by an Islamic holy man possessed of special healing gifts.

Red spirits or zar, on the other hand, are largely benevolent, though, like the humans they possess, they are capable of mischievous and even dangerous behavior. Unlike black spirits, they cannot be exorcised, remaining with a host throughout her life. It is sometimes said that everybody has one or more of these possessing red spirits, which are frequently inherited, often from a relative in the female line. Unless it is bothered, the spirit remains quiet, causing no obvious sign of its presence, but usually letting its human host know of its preference for certain food stuffs, or for items of clothing or jewelry. If something upsets it, however (for example, if the host ignores its preferences), it can cause difficulties for the host, such as illness or family problems. She is then advised to seek the remedy through consultation with a local zar group leader.

Known as wind, Red Wind (al-rih al-ahmar), zar spirits have been compared to electricity, able to penetrate solid spaces and bodies, but in and of themselves invisible and incorporeal. They achieve a visible identity only by possessing humans, who humor their demands for specific dress, accessories and behavior to avoid further disruption. Their existence is justified by the widespread belief that they were known to the Prophet Muhammad, said to be mentioned in the Hadith (accounts of the Prophet’s sayings and deeds). There are hundreds of different zar spirits, the actual number vague, with new spirits continuing to appear and old spirits disappearing or at least forgotten. Some are named and well-defined, others known only as part of a group. All, however, are grouped into “nations,” which are found uniformly in Sudanese zar today and which reflect the historical context of the region. In terms of the order in which they are summoned on formal ritual occasions, these are: Darawish, Pashas, Khawajat, Habbash, Arabs, Blacks, and (a separate category) the Ladies (al-Sittat). They are discussed further below.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

There are several distinct levels of zar ritual in Sudan today, similar in both zar burei and tombura. At a basic level, the leader of a local group (known as al-ummiya or al-shaikha) is available for consultation, often at any time of day or night. A person who believes her or his problems may be related to zar is advised to seek such a consultation to determine exactly what is going on. In a room generally reserved for zar activities, the leader opens her box (al-sandug) of ritual paraphernalia, including special incenses believed to summon the spirits, and on a pot of burning coals drops a few pinches of incense. This she uses to fumigate or cleanse the client’s body as well as to inhale herself. The process may then lead her into trance, during which she can communicate with the spirits. For the most part, zar spirits do not communicate verbally, but during the trance experience (and in her sleep later) the leader is believed to be in contact with the zar spirit(s) possessing the client, to determine their identity and the cause of their unrest. In this indirect way, the spirits’ wishes are communicated to the patient. During such consultations, which occur frequently, there is no music or dancing, no special dress for the spirits, and no refreshments, unless the patient has bought gifts of chickens or pigeons to be offered to the zar.

This event marks the beginning of a person’s career in zar and her relationship with a local leader, to whom she will remain attached for the rest of her life. She visits the leader whenever she needs and, for a small sum, can  contact the spirits possessing her through the leader’s intercession. She will also be called to attend more formal rituals at the leader’s house of zar and to support these as much as she can with money and/or services.

contact the spirits possessing her through the leader’s intercession. She will also be called to attend more formal rituals at the leader’s house of zar and to support these as much as she can with money and/or services.

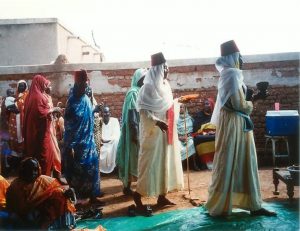

The chair, al-kursi, is a more formal level of ritual and occurs when a woman who is seriously troubled by one or more zar spirits can afford to sponsor it. Optimally a kursi should last for seven days, though if this expense is beyond the means of the sponsor of the event, a three-day or even one-day event is possible. The spirits (and the various hosts they possess), however, prefer the full week of celebrating. During this period, the whole community (al-jama‘a) of spirits is called down to visit their hosts, many women simultaneously being possessed by the same spirit. First to come down on all formal ritual occasions are the Darawish, spirits of Islamic (Sufi) holy men. [Image at right] The women they possess don long white jalabiya (a loose garment covering the whole body except the head), cover their heads, and lean on Sufi walking sticks, looking sage and solemn. After the Darawish leave, the women shake off their possession, reemerging, somewhat dazed, to the hugs and smiles of their friends. Soon afterwards, different drum beats, song and incense summon the Pashas, spirits of nineteenth-century Egyptian  noblemen, directly “from the palaces.” [Image at right] The women who become possessed by them now pull out white or cream jalabiya, and the leader hands out red fez (hats) from her collection of accessories, for the spirits to enjoy. Once the Pashawat spirits all leave, the drum beats change again, and summon the Khawajat, spirits of European colonial officers. Their dress preferences are quite varied, and often hinge on just one item of clothing (a scarf, a necktie) which serves to distinguish the spirit. The behavior of these spirits, in the recent past, has been arrogant and drunken (even when no alcohol was consumed), encouraged by the politics of Sudan in the late twentieth century, when relations with the West became increasingly strained. Khawajat spirits are followed in turn by the Habbash (Ethiopians), Arabs (spirits of nomadic warriors), and Blacks (fierce warrior spirits from Central Africa), who likewise are distinctive for both dress preferences and body language. All of these spirits are male. A final group or nation, the Ladies, al-Sittat, includes females from all the other nations, past and present. The Ethiopian women are awaited particularly eagerly, and when they visit, extravagant dresses and jewelry are enthusiastically displayed.

noblemen, directly “from the palaces.” [Image at right] The women who become possessed by them now pull out white or cream jalabiya, and the leader hands out red fez (hats) from her collection of accessories, for the spirits to enjoy. Once the Pashawat spirits all leave, the drum beats change again, and summon the Khawajat, spirits of European colonial officers. Their dress preferences are quite varied, and often hinge on just one item of clothing (a scarf, a necktie) which serves to distinguish the spirit. The behavior of these spirits, in the recent past, has been arrogant and drunken (even when no alcohol was consumed), encouraged by the politics of Sudan in the late twentieth century, when relations with the West became increasingly strained. Khawajat spirits are followed in turn by the Habbash (Ethiopians), Arabs (spirits of nomadic warriors), and Blacks (fierce warrior spirits from Central Africa), who likewise are distinctive for both dress preferences and body language. All of these spirits are male. A final group or nation, the Ladies, al-Sittat, includes females from all the other nations, past and present. The Ethiopian women are awaited particularly eagerly, and when they visit, extravagant dresses and jewelry are enthusiastically displayed.

A special welcome is reserved for the spirit, or spirits, troubling the sponsor of the event. For them, animal sacrifice is made, and special foods and beverages are served (according to their known preferences). The various women they possess all wear the clothes and accessories that are known to please them, many of which are drawn largely from the later nineteenth century. They may come down to possess women more than once during the ceremony and are treated with particular courtesy and respect.

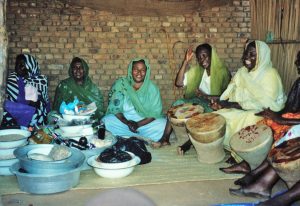

During the ninth Islamic month of Rajab, in a ritual similar to the kursi, each house or group of zar in turn is expected to host a thanksgiving, al-karama, so that the whole month is taken up with successive thanksgiving ceremonies. [Image at right] On this occasion, the leader herself is the hostess, supported by all the members of her zar house. This is when she reaffirms her relationship with the spirits as well as gains recognition from other leaders, who are invited to attend each other’s events. This is the grandest annual event in zar and each leader inherits a specific date on which she can open her ritual karama. Only the most senior leader in an area can hold her thanksgiving on the 27th day of Rajab, a particularly holy day in the Sufi calendar.

Finally, special ritual surrounds the “girding” or inauguration of a new leader in zar. This occurs rarely; there are only five houses of burei zar in Sennar district today, and leadership is a lifetime commitment to which many aspire but few actually achieve. The ritual in the girding again draws on that of the kursi, optimally lasting seven days, but this is hosted by the new leader and her family. Her actual inauguration, with all the spirits present in her supporters’ bodies, is the culmination of the ceremony. This is performed by the leader with whom she trained, aided by other zar leaders from the district. The specific ritual draws heavily on the symbolism of similar Sufi Brotherhood events.

Beginning in the 1970s, another informal level of ritual was introduced, known colloquially as the coffee (al-jabana). This led to a further proliferation of zar activity, as well as made it less expensive, and therefore more accessible, for those of limited means. A lowly Habbash (Ethiopian) spirit named Bashir possessed the ummiya Rabha, granddaughter of Zainab, and was served coffee, as was deemed appropriate for an Ethiopian. He announced that he intended to visit her every Sunday (appropriate for a Christian spirit like himself) and invited people to come and consult with him. Ten years later, Bashir was visiting (possessing) several other women around town on Sundays, and sometimes other days as well. For a small sum, their friends and  neighbors were able to join him for coffee and bring their concerns to him. Unlike other zar spirits, who only communicate non-verbally through the ummiya, Bashir chats with his guests, albeit in a broken Arabic, and often jokes and entertains them as well. [Image at right]

neighbors were able to join him for coffee and bring their concerns to him. Unlike other zar spirits, who only communicate non-verbally through the ummiya, Bashir chats with his guests, albeit in a broken Arabic, and often jokes and entertains them as well. [Image at right]

By the early twenty-first century, two other spirits were visiting adepts with powerful zar, said to be half-siblings of Bashir, and performing similar services: Dasholay, his half-brother who shares Bashir’s Ethiopian mother but has a Sudanese soldier father, and displays a gruffer, more serious demeanor than Bashir; and Luliya, their half-sister, an enormously popular spirit, who embodies all that is beautiful and feminine in the Sudanese context, and to  whom people bring concerns about sexuality, including pregnancy, childbirth, and homosexuality. [Image at right] Interestingly these three spirits are described as lowly servants (al-khudam), and as their profiles are detailed, it becomes apparent that they not only connect back to the Ottoman ranks, but are grounded in the slave culture of the nineteenth century. Even more significant, the popularity of these three spirits (Bashir, Dasholay, and Luliya), at all levels of zar practice today, make them the most important and influential zar in Sudan.

whom people bring concerns about sexuality, including pregnancy, childbirth, and homosexuality. [Image at right] Interestingly these three spirits are described as lowly servants (al-khudam), and as their profiles are detailed, it becomes apparent that they not only connect back to the Ottoman ranks, but are grounded in the slave culture of the nineteenth century. Even more significant, the popularity of these three spirits (Bashir, Dasholay, and Luliya), at all levels of zar practice today, make them the most important and influential zar in Sudan.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Despite occasional assertions to the contrary, there is no overarching organization in zar, burei or tombura, and no recognized overall leadership. Organization is largely local, and while some seniority is recognized at that level among zar leaders, it can change over time. One of the biggest differences between zar burei and tombura, however, is found in their organization. Tombura is somewhat hierarchical, with a male leader (al-sanjak, a term drawn from Ottoman military titles) overseeing several independent female group leaders, al-shaikhat or al-ummiyat (pl.). The sanjak should be present on any formal ritual occasion, such as a kursi or karama, but day-to-day running of each group’s activities devolves around the shaikha.

Burei, on the other hand, remains a strictly acephalous organization. Each leader inherits her status through a seven-year apprenticeship with another leader, followed by her inauguration, at which time she is said to open her own box, independent of her mentor, from whose practice her own zar will now diverge. She thus remains linked to her “senior mother” in zar, but to all other leaders she is equal. This status is reinforced when she is invited to attend a ceremony in one of the other houses of zar, for a Rajab ceremony or a girding. She takes her own  incense to protect herself and her spirits from possible envy or challenges in this alien environment, but is otherwise treated as an honored, and equal, guest.

incense to protect herself and her spirits from possible envy or challenges in this alien environment, but is otherwise treated as an honored, and equal, guest.

In both burei and tombura, each leader is assisted by “girls” (women in training themselves for strengthening their powers in zar) who prepare her incenses; keep the incense pot filled and fumigate patients seeking help; watch over the leader as she becomes possessed and help keep wayward spirits in check; stock up the needed supplies; or simply keep the leader company in what is a very demanding and time-consuming job. Some of these helpers anticipate becoming leaders themselves at some point, and commit increasing personal time and resources to their assistance in a formal seven-year apprenticeship. [Image at right] Few actually succeed in achieving this goal.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

From the earliest written accounts of zar, these beliefs and practices have been associated with the “primitive” behavior of women, belittled by male observers, local and international, academic and kin, alike. Academically this view is associated with the writings of anthropologist I. M. Lewis (1930–2014), and it continues to influence some of the writings about Sudanese zar (Lewis 1971). While this may shape outsiders’ views of zar, however, it is a matter of indifference or ridicule to adepts, who feel this shows just how little outsiders actually know about zar.

In the twenty-first century, zar adepts confronted a range of other challenges. Most critical has been the rise of political Islam. The Islam that spread in this region as early as the fifteenth century was shaped by Sufi ideology and tolerance. Since the middle of the twentieth century, however, a more radical, Wahhabi-influenced form of Islam has gained ascendance, culminating in the imposition of Shari‘a law in 1983 and the subsequent military coup of 1989, which established an Islamic state. In the 1990s, zar activities were actively banned, rituals raided, and leaders beaten, fined, and even thrown into prison. While these threats were no longer in force by 2000, women were reluctant to hold their ceremonies in popular places, preferring obscure homes in poorer neighborhoods, away from watchful Islamist eyes and security officials. Curfews were carefully observed, even when they seem to have been lifted officially, and wayward Khawaja (European) or Black spirits were denied their demands for strong liquor, something no longer available since Shari‘a law came into effect.

For many strict Muslims today, zar is seen as haram (forbidden), even blasphemy. Beliefs that possessed zar adepts drink blood and alcohol as part of the ritual remain widespread, fueling this view. This may have been so a century ago, but in living memory the perfume named “Sudanese Girl” (Bit as-Sudan) is described as blood and ritually drunk, mixed with burnt incense, to appease the spirits. Alcoholic drinks are no longer available, and this is said to be a major reason why European spirits no longer visit. Zar is also seen as anti-Islamic, even though much of its organization and ritual is derived from Sufi roots. In increasing numbers, however, Sudanese men and women have been going on the pilgrimage to Mecca and return with strengthened Wahhabi ideas about Islam. These include views on zar, which is banned in the Saudi kingdom.

In the last half century, widespread literacy and education, especially for women, have also influenced ideas about zar. Through school and mosque, women are learning modern ways to think, and this includes regarding zar as backward, primitive, and obsolete. The Islamic state’s efforts to produce strict Muslims and modern citizens made no accommodations for the rituals and beliefs of zar. These views were reinforced by government-controlled television programs about Sudan and its cultures, in which zar was variously represented as quaint traditional culture or as something forbidden to good Muslims. Television itself has also had a major impact on Sudanese life. The scheduling of popular soap operas during the evening hours, traditionally regarded as times to visit neighbors, has led to a breakdown in local social activities and the easy visiting between households that characterized communities only a generation ago, which helped facilitate the popularity of informal and formal zar activities.

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGIONS

Sudanese society, like much of the Muslim world, continues to be divided by gender segregation, and zar today is regarded as distinctly part of women’s culture, even as it is celebrated as part of traditional Sudanese culture. It remains one area of knowledge where men invariably defer to women’s understandings, even though in the past men were active in its practice and organization. In Sennar, people remember Zainab’s husband Marajan, who practiced zar nugara, with its terrifying rituals involving dancing on hot coals and consuming boiling water. These are cited as examples of how demanding zar was formerly when men were in charge.

Throughout Sudanese history, however, it was men who were first pressured to change and adapt: to convert to Islam, to become good colonial citizens, to become educated members of the modern nation state. This left zar increasingly in the hands of women, if it was not there already. Nugara disappeared and the forms of zar found today are more genteel, even as they continue to meet the needs of those troubled by symptoms diagnosed as zar possession. Men may enter trance in Sufi rituals, but possession by the red spirits is now almost entirely a female sphere, where understanding of the “supernatural” is tempered by nurturing and hospitality, and interactions with the spirit world can become a wonderful, dramatic, colorful party.

Finally, it is worth noting that while spirit possession can seem a strange, unnatural phenomenon to outsiders, skeptics, and nonbelievers, it occurs in the majority of societies (Bourguignon 1991; Di Leonardo 1987). Despite efforts to suppress such “possession religions,” they have shown remarkable resilience, and continue to attract new adepts. Some writers have related this to situations in which oppression and social violence are commonplace (e.g. Kwon 2006; Lan 1985). Others (e.g. Lambek 1993; Palmié 2002) have shown that not only does spirit possession continue to meet local needs, but also offers alternative epistemologies that challenge prevailing modernist rhetoric as well as our assumptions about religion and contemporary life.

IMAGES

Image #1: Darawish spirit. Photo by author in Sennar, 2001.

Image #2: Pashawat spirits in procession. Photo by author in Sennar, 2001.

Image #3: Karama, with musicians and kursi of offerings to the zar. Photo by author in Sennar, 2004.

Image #4: Zar consultation with Bashir. Photo by author in Sennar, 2001.

Image #5: Al-Sittat (Luliya). Photo by author in Sennar, 2001.

Image # 6: Dasholay with assistant and box. Photo by author in Sennar, 2004.

REFERENCES

Al-Nagar, Samia al-Hadi. 1975. “Spirit Possession and Social Change in Omdurman.” M.Sc. Thesis. University of Khartoum.

Boddy, Janice. 1989. Wombs and Alien Spirits. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Bourguignon, Erika. 1991. Possession. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press

Constantinides, Pamela. 1972. “Sickness and the Spirits: A Study of the ‘Zar’ Spirit Possession Cult in the Northern Sudan.” Ph.D. dissertation. London University.

Di Leonardo, Micaela. 1987. “Oral History as Ethnographic Encounter.” Oral History Review 15:1–20.

Hurgronje, C. Snouck. 1931. Mekka in the Latter Part of the 19th Century. Leyden: E. J. Brill.

Kenyon, Susan M. 2012. Spirits and Slaves in Central Sudan: The Red Wind of Sennar. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Klunzinger, C. B. 1878. Upper Egypt: Its People and Its Products. London: Blackie & Son.

Kwon, Heonik. 2006. After the Massacre: Commemoration and Consolation in Ha My and My Lai. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lambek, Michael. 1993. Knowledge and Practice in Mayotte: Local Discourses of Islam, Sorcery, and Spirit Possession. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Lan, David. 1985. Guns and Rain: Guerillas and Spirit Mediums in Zimbabwe. London: James Curry.

Lewis, I. M. 1971. Ecstatic Religion. Harmondsworth, U.K.: Penguin Books.

Lewis, I. M., A. al-Safi, and Sayyid Hurreiz, eds. 1991. Women’s Medicine: the Zar-Bori Cult in Africa and Beyond. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press for the International African Institute.

Makris, G. P. 2000. Changing Masters: Spirit Possession and Identity Construction among Slave Descendants and Other Subordinates in the Sudan. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Natvig, Richard. 1987. “Oromos, Slaves, and the Zar Spirits: A Contribution to the History of the Zar Cult.” International Journal of African Historical Studies 20:669–89.

Palmié, Stephan. 2002. Wizards and Scientists: Explorations in Afro-Cuban Modernity and Tradition. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Seligman, Brenda Z. 1914. “On the Origin of Egyptian Zar.” Folklore 25:300–23.

Post date:

20 November 2019