HINDUISM TIMELINE

3600-1700 BCE The first attested elements that can be argued to be “Hindu” were found in the Indus Valley civilization complex.

1900 BCE The Sarasvati River dried up due to climate changes. Indus-Sarasvati culture ended; the center of civilization in ancient India relocated from the Sarasvati River to the Ganges River.

1500 BCE The Rig Veda Samhita (the earliest extant text in Hinduism) was compiled.

1000 BCE The three original Vedas (Rig, Yajur, and Sama) were completed, and Sanskrit declined as a spoken language over the next 300 years.

800 to 400 BCE The Orthodox Upanishads were compiled, and with them came the development of the concept of unity of the individual soul (atman) with Infinite Being (brahman).

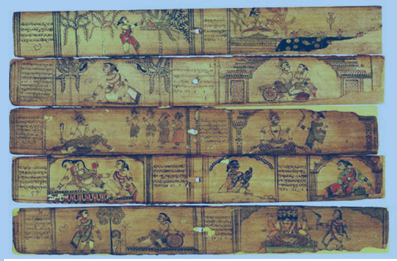

500 to 200 BCE Over these 300 years numerous secondary Hindu scriptures ( smriti ) were composed: Shrauta Sutras, Grihya Sutras, Dharma Sutras, Mahabharata, Ramayana, Puranas, and others.

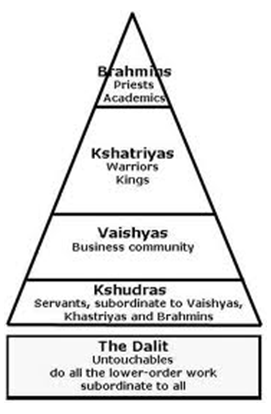

c. 400 BCE Dharmashastra of Manu developed. Its verses codified cosmogony, four ashramas, government, domestic affairs, caste, and morality.

300 BCE to 100 CE The Tamil Sangam age began. Sage Agastya wrote Agattiyam, first known Tamil grammar. Tolkappiyar wrote Tolkappiyam, a summary of earlier works on grammar, poetics, and rhetoric, indicating prior high development of Tamil. Gave rules for absorbing Sanskrit words. At this time, Tamil literature referred to worship of Vishnu, Indra, Murugan, and Supreme Shiva. Pancharatra Vaishnavite sect was prominent. All later Vaishnavite sects were based on the Pancharatra beliefs (formalized by Sandilya about 100 CE).

c. 200 BCE to 200 CE Patanjali wrote the Yoga Sutra.

c. 200 BCE to 100 CE Jaimini wrote the Mimamsa Sutra.

c. 100 Kapila, founder of the Samkhya philosophy, one of six classical systems of Hindu philosophy was born. Sandilya, the first systematic promulgator of the ancient Pancharatra doctrines, was born. His Bhakti Sutras, devotional aphorisms on Vishnu, inspired a Vaishnavite renaissance. By 900 CE the sect had left a permanent mark on many Hindu schools. The Samhita of Sandilya and his followers embodied the chief doctrines of present-day Vaishnavites.

200 Hindu kingdoms were established in Cambodia and Malaysia.

c. 250 The Pallava dynasty (c. 250–885) was established in Tamil Nadu. They erected the Kamakshi temple complex at the capital of Kanchipuram and the great seventh-century stone monuments at Mahabalipuram.

320 The Imperial Gupta dynasty (320–540) emerged. During this “Classical Age” norms of literature, art, architecture, and philosophy were established. This North Indian empire promoted both Vaishnavism and Saivism and, at its height, ruled or received tribute from nearly all India. Buddhism also thrived under tolerant Gupta rule.

c. 600–900 Twelve Vaishnava Alvar saints of Tamil Nadu flourished, writing 4,000 songs and poems praising Vishnu and narrating the stories of his avatars.

c. 700 Over the next hundred years the small Indonesian island of Bali received Hinduism from neighboring Java. Stone-carving and sculptural works were completed at Mahabalipuram.

788 Shankara (788–820) was born in Malabar. The famous monk-philosopher established ten traditional monastic orders, and developed Advaita Vedanta, which would become the foundation of modern Hinduism.

c. 800 Vasugupta, modern founder of Kashmiri Shaivism, a major monistic, meditative school was born. Andal, girl saint of Tamil Nadu was born. She wrote devotional poetry to Lord Krishna, but she disappeared at age sixteen.

c. 400 Vatsyayana wrote Kama Sutra, the famous text on erotics. Karaikkalammaiyar, a woman and the first of the 63 Shaivite saints of Tamil Nadu, died.

c. 500 Sectarian folk traditions were revised, elaborated, and recorded in the Puranas, Hinduism’s encyclopedic compendium of culture and mythology.

c. 880 Nammalvar (c. 880–930), the greatest of Alvar saints, was born. His poems shaped beliefs of southern Vaishnavites to the present day.

c. 900 Matsyendranatha, exponent of the Nath sect emphasizing kundalini yoga practices and important progenitor of vamacara (left-handed) Tantric lineages, was born.

950 Kashmiri Shaivite guru Abhinavagupta (950–1015), composer of the Tantraloka , which is considered the most important surviving work on Kashmir Shaiva Tantra, was born.

1077 Ramanuja (1077–1157) of Kanchipuram, Tamil philosopher-saint of the Sri Vaishnavite sect, was born.

1106 Basavanna (1106–1167), founder and guru of the Virashaiva sect, was born.

c. 1150 The Khmer ruler completed Angkor Wat temple (in present-day Cambodia), the largest Hindu temple in Asia.

c.1200 Gorakhnath, famous Nath yogi was born. All of North India was by this time under Muslim domination.

c. 1300 Lalleshvari (c. 1300–1372) of Kashmir, Shaivite renunciant and mystic poet was born. She contributed significantly to the Kashmiri language.

1336 The Vijayanagara empire (1336–1646) of South India was founded.

c. 1400 Kabir, Vaishnavite, a reformer who had both Muslim and Hindu followers, was born. His Hindi songs have remained immensely popular.

1449 Shankaradeva, an important Assamese reformer and composer who emphasized music as worship, forbade temple ritual, and converted the bulk of the population of Northeast India to devotional Vaishnavism, was born.

1450 Mirabai (1450–1547), a Vaishnavite Rajput princess-saint devoted to Lord Krishna, was born.

1473 Vallabhacharya (1473–1531), a saint who taught pushtimarga, “path of grace,” was born.

1486 Chaitanya (1486–1533), the Bengali founder of popular Vaishnavite sect that proclaimed Krishna as Supreme God and emphasized group chanting and dancing, was born.

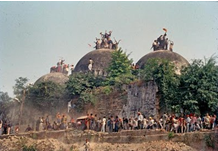

1526 The Muslim conqueror, Babur (1483–1530), occupied Delhi and founded the Indian Mughal Empire (1526–1761).

1532 Monk-poet, Tulsidas (1532–1623), author of Ramcharitmanasa (1574–77) (based on Ramayana), which significantly advanced worship of Rama, was born.

1556 Akbar (1542–1605), grandson of Babur, became the third Mughal emperor, promoting religious tolerance.

1600 A royal charter formed the East India Company, setting in motion a process that ultimately resulted in the subjugation of India under British rule.

1608 Tukaram (1608–1649), saint famed for his poems to Krishna was born. He is considered greatest Marathi spiritual composer.

1658 Zealous Muslim Aurangzeb (1618–1707) became Mughal emperor.

1718 Ramprasad Sen (1718–1780), one of the most famous Bengali poet-saints and worshipper of goddess Kali, was born.

1751-1800 Major victories over regional rulers in North and South India gave the British increasing control over the subcontinent.

1786 Sir William Jones used the Rig Veda term Aryan (noble) to name the parent language of Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, and Germanic tongues.

1803 The Second Anglo-Maratha War resulted in the British capture of Delhi and control of large parts of India. Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), an American poet who helped popularize Bhagavad Gita and Upanishads in the United States was born.

1824 Swami Dayananda Sarasvati (1824– 1883), founder of Arya Samaj (1875), a Hindu reformist movement stressing a return to the values and practices of the Vedas, was born.

1828 Rammohan Roy (1772–1833) founded Brahmo Samaj in Calcutta (Kolkata). Influenced by Islam and Christianity, he denounced polytheism and idol worship.

1836 Sri Paramahansa Ramakrishna (1836– 1886), God-intoxicated Bengali saint, devotee of goddess Kali, and guru of Swami Vivekananda, was born.

1820s-1920s Hindus from India began to enter the United States as immigrants, and were sent to British colonies in the Caribbean region, Fiji, Africa, and South America as indentured laborers.

1853 Sri Sarada Devi (1853–1920), wife of Sri Ramakrishna, lineage holder in the Ramakrishna tradition and inspiration for the Sarada Math convent for women, was born.

1853 Max Mü ller (1823–1900), German Sanskrit scholar in England, at this time advocated the term Aryan to describe speakers of Indo-European languages.

1857 The first major Indian revolt against British rule, the “Sepoy Mutiny,” occurred.

1861 Bengali poet, Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature in 1913.

1863 Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902), important dynamic missionary to the West and catalyst of major Hindu revival in India, was born..

1869 Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869–1948), Indian nationalist and Hindu political activist, who developed the strategy of nonviolent disobedience that led to the independence of India (1947) from Great Britain, was born.

1872 Sri Aurobindo Ghose (1872–1950), Bengali Indian nationalist and yoga philosopher, was born.

1879 Sri Ramana Maharshi (1879–1950), Hindu advaita renunciant saint of Tiruvannamalai, South India and a major international spiritual leader, was born.

1887 Swami Shivananda (1887–1963) was born. He was a renowned universalist teacher, author of 200 books, founder of Divine Life Society in Rishikesh, and guru to many teachers who brought Hinduism to the West.

1893 The World Parliament of Religions in Chicago recognized Eastern religious traditions through presentations by representatives of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism. Swami Vivekananda received acclaim as spokesperson for Hinduism.

1896 Anandamayi Ma (1896–1982), God-intoxicated yogini and mystic saint of Bengal, was born. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (1896–1977) was born. In 1966, he founded International Society of Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) in the United States.

1908 Swami Muktananda (1908–1982) was born. He became a guru of the Kashmiri Shaivite school that founded Siddha Yoga Dham to promulgate Indian mysticism, kundalini yoga, and philosophy throughout the world.

1912 Anti-Indian racial riots occurred on the U.S. West Coast that led to the expulsion of Hindu immigrants.

1918 Sai Baba of Shirdi (1856–1918), saint to Hindus and Muslims, died at approximately age 62.

1920 Mohandas K. Gandhi (1869–1948) used “truth power” (satya-grah), which was first articulated in South Africa as a strategy of noncooperation and nonviolence against India’s British rulers.

1920 Paramahansa Yogananda (1893–1952), famous author of Autobiography of a Yogi, teacher of kriya yoga and Hindu guru with many Western disciples, entered the United States, where he founded the Self-Realization Fellowship (1935).

1925 K. V. Hedgewar (1890–1949) founded Rashtriya Swayam Sevak Sangh (RSS), a militant Hindu nationalist movement.

1927 Maharashtra barred the tradition of dedicating girls to temples as Devadasis, ritual dancers. Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Orissa soon followed suit. Twenty years later, Tamil Nadu banned devotional dancing and singing by women in its temples and in all Hindu ceremonies.

1947 (August 15) India gained independence from Britain.

1949 India’s new constitution, authored chiefly by B. R. Ambedkar, declared there shall be no “discrimination” against any citizen on the grounds of caste (jat i) and abolished the practice of “untouchability.”

1964 India’s Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP), a Hindu religious nationalist movement, was founded to counter secularism.

1964 The rock group, the Beatles, practiced Transcendental Meditation (T.M.), making Maharshi Mahesh Yogi famous.

1980 The Hindu nationalist party, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), was founded.

1992 Hindu radicals demolished Babri Masjid, which was built in 1548 on Rama’s birthplace in Ayodhya by Muslim conqueror Babur after he destroyed a Hindu temple marking the site.

1994 A Harvard University study identified more than 800 Hindu temples open for worship in the United States.

1998-2004 The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) served as India’s ruling party.

2001 History’s largest human gathering, seventy million people, worshipped at Kumbha Mela in Allahabad, at the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna Rivers.

Present Hinduism has continued to grow in most countries of the old diaspora: Fiji, Guyana, Trinidad, Mauritius, Malaysia, and Suriname. Europe and the United States have continued to be destinations for the current participants in the diaspora. Descendants have maintained their faith and identity, while non-Indian converts to the religion continue to increase in number.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Until the nineteenth century, Hinduism was considered the indigenous religion of the sub-continent of India and was practiced largely in India itself and in the places where Indians migrated in large numbers. In the twenty-first century, while still centered upon India, Hinduism is practiced in most of the world’s countries and can thus rightly be considered a world religion. Its creation, unlike some world religions founded by known historical leaders, reaches into pre-history; we do not know the individuals who first practiced the religion (or set of religions that have merged to constitute present-day Hinduism), nor do we know exactly when its earliest forms emerged.

“Hindu” is a term that comes from the ancient Persians. The Sindhu River in what is now Pakistan was

called the “Hindu” by the Persians (the first textual mention occurring perhaps in the last centuries before the Common Era). So the people who lived in proximity to the Sindhu therefore came to be called Hindus (Lipner 1994:7).

called the “Hindu” by the Persians (the first textual mention occurring perhaps in the last centuries before the Common Era). So the people who lived in proximity to the Sindhu therefore came to be called Hindus (Lipner 1994:7).

The first attested elements that can be argued to be “Hindu” are found in the Indus Valley civilization complex, which lay geographically in present day Pakistan. This civilization complex, which is contemporaneous with Sumeria, and matches it in complexity and sophistication, is dated 3600-1900 BCE. Considerable debate exists in regard to the relationship of the Indus Valley civilization and the later Vedic tradition that focused on fire worship. The scholarly consensus for many years held that the Aryans, people who came from the West through Iran, arrived in India no earlier than 1200 BCE., much too recent to have participated in the Indus Valley world, which by then had largely collapsed due to complex environmental, political, and economic factors (Kenoyer 1998:174). These people were, the view holds, associated with the transmission of the Vedas , India’s most sacred and revered texts. This consensus has been challenged, primarily from the Indian side, and continues to undergo scrutiny. The alternative view rejects the notion that the people who gave India the Vedas were originally foreign to India and sees a continuity between India’s earliest civilization and the people of the Vedas (Bryant 2001:45).

The Rig Veda (c. 1500 BCE), which everyone agrees is the most ancient extant Indian text, is the

foundational text of Hinduism. It consists of about a thousand hymns. The great majority of the hymns are from five to twenty verses in length. Very few hymns exceed fifty verses in length. The Rig Veda contains hymns of praise to a pantheon of divinities and a few cosmogonic hymns that tell of the creation of the universe. These stories are extremely important for the development of later Hinduism (Fowler 1997:108).

foundational text of Hinduism. It consists of about a thousand hymns. The great majority of the hymns are from five to twenty verses in length. Very few hymns exceed fifty verses in length. The Rig Veda contains hymns of praise to a pantheon of divinities and a few cosmogonic hymns that tell of the creation of the universe. These stories are extremely important for the development of later Hinduism (Fowler 1997:108).

Two other Vedas, the Yajur and Sama Vedas, were based on the Rig Veda . That is, most of their text comes from the Rig Veda , but the words of prior text are reorganized for the purposes of the rituals. Later, a fourth Veda, the Atharva Veda , became part of the greater tradition. This text is considered the origin of Indian medicine, the system of Ayurveda. Yet, a number of hymns in the Atharva Veda are cosmogonic hymns that show the development of the notion of divine unity in the tradition.

Two important things must be understood about the Vedic tradition. Firstly, none of the Vedas is considered composed by humans. All are considered to be “received” or “heard” by the rishis, divinely inspired sages, whose names are noted at the end of each hymn. Secondly, none of the text of the Vedas was written down until the fifteenth century of the Common Era. The Vedic tradition was passed down from mouth to ear for millennia, and is, thus, the oral tradition par excellence (Flood 1996:39). The power of the word in the Vedic tradition is considered an oral and aural power, not a written one. The chant is seen as a power to provide material benefit and spiritual apotheosis (Heehs 2002:41). The great emphasis, therefore, was on correct pronunciation and on memorization. Any priest of the tradition was expected to have an entire Veda memorized, including its non-mantric portions (explained below).

Any of the four Vedas is properly divided into two parts, the mantra, or verse portion, and the Brahmana , or explicatory portion. Both of these parts of the text are considered revelation or shruti . The Brahmanas reflect on both the mantra text and the ritual associated with it, giving very detailed, varied and arcane explication of them.

The name Brahmana derives from a central word in the tradition, brahman . Brahman is generically the name for “prayer” itself, but technically refers to the power or magic of the Vedic mantras. (It also was used to designate the “pray-er,” hence the term “brahmin.”) Brahman comes from the root brih – “to expand or grow” and refers to the expansion of the power of the prayer itself as the ritual proceeds and is understood as something to be “stirred up” by the prayer. In later philosophy, the term Brahman refers to the transcendent, all encompassing reality (Heehs 2002:58).

Lastly, within the Brahmanas (commonly within the Aranyaka portion), there was the last of the Vedic subdivisions (no one really  knows when these subdivisions were designated) called the Upanishads . Many of these texts shared in the quality of the Brahmanas , as they contained significant material that reflected on the nature of the Vedic sacrifice. So the division, in many cases, between Brahmana proper, Aranyaka and Upanishad is not always clear. The most important feature of the Upanishad was the emergence of a clear understanding of the unity of the individual self or Atman and the all-encompassing Brahman, understood as the totality of universal reality, both manifest and unmanifest (Heehs 2002:58-60).

knows when these subdivisions were designated) called the Upanishads . Many of these texts shared in the quality of the Brahmanas , as they contained significant material that reflected on the nature of the Vedic sacrifice. So the division, in many cases, between Brahmana proper, Aranyaka and Upanishad is not always clear. The most important feature of the Upanishad was the emergence of a clear understanding of the unity of the individual self or Atman and the all-encompassing Brahman, understood as the totality of universal reality, both manifest and unmanifest (Heehs 2002:58-60).

The genesis of the Upanishadic understanding of the unity of self and cosmic reality is clear. Firstly, the Shatapatha Brahmana stated that the most perfect ritual was, in fact, to be equated to the universe itself. More accurately it was the universe, visible and invisible. Secondly, the Aranyakas made clear that each individual as an initiated practitioner was the ritual itself. So, if the ritual equals all reality and the individual adept equals the ritual, then the notion that the individual equals all reality is easily arrived at (Hopkins 1971:32-33). The Upanishads were arrived at, then, not by philosophical speculation, but by ritual practice. Later Upanishads of the orthodox variety (that is, early texts associated with a Vedic collection) omitted most reference to the ritual aspect and merely stated the concepts as they had been derived. Most importantly, the concepts of rebirth and the notion that actions in this life would have consequence in a new birth were first elaborated in the Upanishads.

This evidence shows that the concept of karma, or ethically conditioned rebirth, had its roots in earlier Vedic thought. But the full expression of the concept of karma was not found until the later texts, the Upanishads, called the Vedanta, the end or culmination of the Vedas (Heehs 2002:59). Therefore, the notion of reaching unity with the ultimate reality was seen as not merely a spiritual apotheosis, but also a way out of the trap of rebirth (or re-death).

After the sixth century BCE, Buddhism and Jainism gained popularity throughout India. However, by the third century, both faced a decline, though some doctrines and practices, such as asceticism and vegetarianism, deeply influenced the broader society (Basham 1989:57-67). The culture and tradition represented by the great epics Ramayana and Mahabharata showed the emergence of the forms of religion called, in current academic terms, “Hinduism.” These specifically show a contrast to the forms found in earlier Vedic “Brahmanism” (Basham 1989:100).

In the Sanskrit epics, still widely known in myriad versions in India today, the gods Shiva and Vishnu began to emerge as the focal points for cultic worship. Shiva appears to be a god of the Himalayas who was identified by the Brahmins with the god Rudra of the Vedas. In all likelihood, the cultic Shiva was fashioned from an amalgam of traditional sources over many centuries (Kramrisch 1981). This pattern of taking local traditions and creating direct connection of them with the Vedas was an ongoing feature in the evolution of the Brahmanical tradition.

points for cultic worship. Shiva appears to be a god of the Himalayas who was identified by the Brahmins with the god Rudra of the Vedas. In all likelihood, the cultic Shiva was fashioned from an amalgam of traditional sources over many centuries (Kramrisch 1981). This pattern of taking local traditions and creating direct connection of them with the Vedas was an ongoing feature in the evolution of the Brahmanical tradition.

Similarly, Vishnu and his numerous avataras emerged from a mélange of cultural sources. Vishnu in the Vedas was not at all a significant divinity. But the cult of Vishnu was organized around a sense of continuity with this Vedic divinity and the larger monistic philosophy that developed in the Vedic tradition (Sadasivan 2000:18). The epic Ramayana is understood to be a story of the descent of Vishnu to earth in order to defeat the demons. Likewise, Krishna, as warrior, another important avatar of Vishnu, was central to the Mahabharata epic. In both epics, stories of Shiva also are found scattered throughout.

A similar phenomenon occurs in the creation of the Great Goddess, Shakti, in Hindu tradition. Shakti forms the third large cultic center in Hinduism, that of the goddess, whose worshippers, called Shaktas, believe in the supremacy of the goddess. The development of Shakti worship began to take shape at the beginning of the Common Era, some centuries later than the developments in the other cultic contexts (Pintchman 1994).

The Bhagavadgita, (c. 100 BCE), which is found in the Mahabharata (Mbh) identifies the god Krishna with the brahman of the

Upanishads. The likelihood is that Krishna was a divinity of certain western Indian groups, who had reached such popularity that he could not be ignored. It may have been that Krishna was originally a tribal chieftain. In the Mahabharata itself he is only spoken of consistently as God in the Bhagavadgita, a clearly later addition to the MBh (Glucklich 2008:107). This identification of a local god with the highest divinity (and further with Vishnu), shows a pattern that led to the incredible diversity of Hinduism. All across India in the next thousand years numerous local gods and goddesses were taken up into the larger Hindu tradition in a process called “Sanskritization” or “Brahmanization” (Padma 2001:117).

Examples from as far away as south India, the last area of India to be influenced by elements of the Aryans, demonstrate the process of absorption of local divinities into the larger Hindu pantheon. Lord Venkateshvara of Tirupati, in Andhra Pradesh, a hill divinity who may have been worshipped in the same spot for several thousand years, was first identified with Shiva and then later identified as the god Vishnu himself. Tirupati thereupon became part of the Vaishnava tradition and a pilgrimage site of great importance. Similarly, the Goddess Minakshi in the Temple city of Madurai, most probably a goddess of her home region in Tamil Nadu for many, many centuries, was associated with Shiva by being identified as his wife. In fact, she appears late enough not to be identified with Parvati, Shiva’s usual spouse, but as a separate wife. Likewise, the Tamil god Murugan came to be identified as the youngest son of Shiva and Parvati.

Over the era from perhaps 600 BCE until as late as the fourteenth century, various local divinities were slowly but systematically absorbed into the Vedic or Brahmanical tradition. The Sanskrit texts, the Puranas, composed from the fourth to the twelfth centuries CE, tell the tales of the complicated and varied lives of Vishnu, Shiva and the Goddess, but many local tales in local languages and Sanskrit tell the more hidden tales of how these local godly kings and queens became part of the larger tradition. The earliest additions to the pantheon of Hinduism were clearly those gods and goddesses who formed the basis of the Vishnu and Shiva cults (Hopkins 1971:87-89). Parvati was likely a mountain goddess who may have ruled the mountains on her own at one time, but became absorbed in the Shaiva tradition. Likewise, Lakshmi, the wife of Vishnu, has characteristics of a local nature divinity who became identified with Shri of the Vedas .

Vedic ritual tradition saw a revival in the kingdoms of the Guptas during the fourth through sixth centuries CE. This period is often described as a Golden Age of Indian tradition when Sanskrit literature flourished with poets like Kalidasa and the kings patronized Brahmins and reestablished Vedic rites that had long languished. Except for this passing phase however, Vedic ritual tradition lost its supremacy very early. By the turn of the Common Era, worship of the major cults had expanded greatly and by the sixth century of the Common Era temples to these divinities began to be created in stone (Dehejia 1997:143-52).

Temple Hinduism represented a real shift in worship from that of the Vedas. Vedic worship had no permanent places of worship, no icons or images, and was not locally bound. Following the traditions of the non-Aryan substratum in India, temple Hinduism focused its worship around icons placed in permanent temples. Most of these temples were positioned in places that had been sites of worship for hundreds and hundreds of years. Part of the shift, however, very much connected the new temple sites with the Aryan tradition: the priests in the temples now were all Brahmins and they all used Sanskrit in the rituals to the gods, whereas before other languages had been used exclusively (Thapar 2004:128-29; Hopkins 1971:110).

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, the British arrived in India and became powerful in Bengal. They succeeded in developing political power through the use of intermediaries carefully chosen from corrupt Muslim potentates and Hindu kings in the chaotic aftermath of Moghul rule (Dirks 2009:1-61).

It is no accident that Hindu modernism began in Bengal, as it represented the longest contact point between the Western ruler, Britain, and its new subjects. English education became the norm for well-educated Bengalis by the early eighteenth century (Acharya 1992:318). When other parts of the country were just getting used to the heavy hand of the British, the Bengalis had already become more than familiar with their views and ways. What emerged was both a reform movement in Hinduism and the roots of the Indian nationalist movement.

Groups emerged in the late eighteenth century, which, influenced in part by Christian ideas, sought to reform Hinduism (Rajkumar 2010:31-37). Groups such as the Brahmo Samaj of Ram Mohan Roy sought to end child marriage, to work for widow remarriage, to eliminate the custom of widows burning themselves on the funeral pyres of their husbands, to eliminate caste, and to cease worship of icons. Many of these people worked from a notion that India had been dominated by the British because the Indian culture had become spiritually corrupt. They felt that if they had had a stronger social sense and greater solidarity, the British could not have so easily come to pre-eminence. Whether this was the case or not, this view was held by nearly every major fighter for Indian Independence including Mahatma Gandhi and Sri Aurobindo (Bhatt 2001:64-67).

The caste system was never a fixed reality in India, and received significant criticism for more than two millennia by various groups who argued from the point of view of a new spiritual vision (Bayly 1999:25-28). The Buddha and Mahavira are the first we know of, starting in 600 BCE, but the Virashaivas of Karnataka, a south Indian state, eliminated caste from their reform tradition in the eleventh century CE, and many groups of mendicant wanderers, like the Siddhas, routinely criticized caste and Brahminical cultural dominance, dating from the Buddha’s time forward. The medieval poet-saints of north India following the views of Kabir, were only repeating a long counter-tradition. So when the “reformists” of Bengal began to attack the social evils of Hinduism it must not be seen as merely a mimicking of Christians and the British. It should be noted, as well, that the anti-iconic movement of the Brahmo Samaj of Calcutta was also not new. The Virashaivas were essentially anti-iconic (except for the Shiva Linga which they kept personally), and the traditional Vedanta of the Upanishads looked to Brahman alone without characteristics (or icons) as the ultimate divinity (Heehs 2002:39-41, 317-18). The Brahmo Samaj takes its name, in fact, from this Brahman spelled as Brahmo in Bengali.

In the rich matrix of Hindu reform in Bengal in the nineteenth century emerged the great saint Ramakrishna and his student Swami Vivekananda. They continued the reformist notions that caste must be uprooted, but Ramakrishna himself was not against worship of icons. What Ramakrishna does though is round out the syncretic movements of the Sants who melded Islamic and Hindu notions while decrying orthodoxy. Ramakrishna directly experienced Islam and Christianity and saw them as alternate paths to the one goal of the Divine. Ramakrishna then brings Hinduism full circle from its Vedic roots where god could be seen as having any face and still be god. But now the social evils that had accrued in Hinduism over the centuries were seen to be superfluous (Rinehart 2004:220-21).

The Indian constitution, ratified in 1949, was written by an untouchable (now referred to as a Dalit), B. R. Ambedkar. Dr. Ambedkar’s selection as the person to head the Constitutional Commission was a sign that the reform values that the Indian independence fighters held were going to be instituted in law in independent India. In the Indian Constitution, “scheduled castes and tribes,” those “out-casted” by traditional Hindu society, were given a specified percentage of guaranteed seats in the Indian Parliament until such time as the Constitution would be amended (Jaffrelot 2000:104). This guarantee was also instituted in nearly every state of the new Indian Union. Additionally, separate electorates were established for Muslims to ensure that Muslims would have adequate representation in the new Indian state. Along with these reforms, inheritance and marriage laws established legal practices to aid women and to counter long-held traditions detrimental to women. Dowry, for instance, a burden for every woman’s family, was outlawed. (Punishment for observing dowry has, regrettably, never been rigorously enforced.) Most importantly, the new state of India was declared a secular state with its own unique definition: it was a state that respected all religions and made accommodations for them, but a state that privileged no single religion (Larson 2010:10). This respect for religion went to the extent of institution, by request of Muslim leaders, of certain laws regarding marriage and property that applied only in the Muslim community. (Muslims, for instance, were allowed to continue the practice of polygyny, of sanctioning as many as four wives to each man.)

Ambedkar’s selection as the person to head the Constitutional Commission was a sign that the reform values that the Indian independence fighters held were going to be instituted in law in independent India. In the Indian Constitution, “scheduled castes and tribes,” those “out-casted” by traditional Hindu society, were given a specified percentage of guaranteed seats in the Indian Parliament until such time as the Constitution would be amended (Jaffrelot 2000:104). This guarantee was also instituted in nearly every state of the new Indian Union. Additionally, separate electorates were established for Muslims to ensure that Muslims would have adequate representation in the new Indian state. Along with these reforms, inheritance and marriage laws established legal practices to aid women and to counter long-held traditions detrimental to women. Dowry, for instance, a burden for every woman’s family, was outlawed. (Punishment for observing dowry has, regrettably, never been rigorously enforced.) Most importantly, the new state of India was declared a secular state with its own unique definition: it was a state that respected all religions and made accommodations for them, but a state that privileged no single religion (Larson 2010:10). This respect for religion went to the extent of institution, by request of Muslim leaders, of certain laws regarding marriage and property that applied only in the Muslim community. (Muslims, for instance, were allowed to continue the practice of polygyny, of sanctioning as many as four wives to each man.)

Independent India began in the chaos of partition. Many Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs were killed in the days after Independence,  when the state of Pakistan was created. Millions crossed the borders on India’s east and west to enter the state that they felt would most protect their interests. Blame has been assigned in many places for the tragic fact of partition. Muslim leaders, Hindu leaders and the British certainly all bore some share of the blame. Conflict ensued over the state of Kashmir, where a Hindu king ceded his majority Muslim state to India at the last minute. This began a long history of wars and disagreements between Pakistan and India that continue in the present day. (Pakistan itself was split in two in 1972, when the state of Bangladesh was created from East Pakistan). For a long time these disagreements did not greatly affect the relationship between Indian Muslims and the Hindu majority.

when the state of Pakistan was created. Millions crossed the borders on India’s east and west to enter the state that they felt would most protect their interests. Blame has been assigned in many places for the tragic fact of partition. Muslim leaders, Hindu leaders and the British certainly all bore some share of the blame. Conflict ensued over the state of Kashmir, where a Hindu king ceded his majority Muslim state to India at the last minute. This began a long history of wars and disagreements between Pakistan and India that continue in the present day. (Pakistan itself was split in two in 1972, when the state of Bangladesh was created from East Pakistan). For a long time these disagreements did not greatly affect the relationship between Indian Muslims and the Hindu majority.

In the 1980’s emerged a new political movement in India (Ludden 1996:4). This movement based itself on the assertion of Hindu majority privilege. It is often referred to as “Hindu fundamentalism,” but this phraseology glosses over the complexities and competing values it represents. Nation states need to justify their existence ideologically. Pakistan shaped its identity from the beginning around Islam, and Hindus and other religions found themselves marginalized there from the beginning. India, however, had preserved the values of a secular state. Muslims regularly held the office of President of India and cabinet posts and were kept visibly in government offices and in positions in the army.

It can be argued that the movement for privileging Hinduism in India and for a call to “Hinduize” India was directly related to the need for a national ideology. (Sarkar 1996: 276). Formation of national identity for new nations is extremely complex, and flows of power are difficult to track, but the emergence of Hindu fundamentalism seems clearly related to this need for the creation of national identity. Hindu self-assertion was not new in India. Certain groups, such as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (The National Self-Help Organization), who admired the fascists in Italy and Germany and taught regimented military tactics for their followers (along with hatred of Muslims), had their roots in Hindu nationalist groups of the nineteenth century (Ludden 1996:13-14). Suffice it to say that hatred of Muslims, conversion of non-Hindu minorities (including Christians) and reassertion of caste privilege were all part of this larger movement. In the 1990’s the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) successfully came to power on this platform and presided over a bloody anti-Muslim massacre in the Indian state of Gujarat (Ludden 1996:18-19). In 2004, they were ousted from power in favor of the Congress Party, the same party that had led India to Independence and had created the secular state of India. During the time of the rise of the Hindu nationalists, great damage was done to relationships between Hindus and Muslims in India. Many Muslims began to retreat into their own fundamentalisms, now global in scope. Others simply left India, if they could. This relationship has remained in deep crisis and will need skillful diplomacy and cultivation to be repaired, if ever it is.

platform and presided over a bloody anti-Muslim massacre in the Indian state of Gujarat (Ludden 1996:18-19). In 2004, they were ousted from power in favor of the Congress Party, the same party that had led India to Independence and had created the secular state of India. During the time of the rise of the Hindu nationalists, great damage was done to relationships between Hindus and Muslims in India. Many Muslims began to retreat into their own fundamentalisms, now global in scope. Others simply left India, if they could. This relationship has remained in deep crisis and will need skillful diplomacy and cultivation to be repaired, if ever it is.

Through European scholarship and interest, Hindu texts and practices became known in Western Europe and North America as early as the eighteenth century. In the nineteenth century, German philosophy, French scholarship and the American Transcendentalist movement served to disseminate Hindu ideas among Western readers, without contributions from Indian emigrants (Klostermaier 2007:420-25). A diaspora, which came to involve the resettlement of significant numbers of emigrants from India, began as early as the seventeenth century and reached significant size between the eighteenth through the twentieth centuries. The pattern of the diaspora was first characterized by indentured laborers arriving in Indonesia, Africa, and the Caribbean region to work the fields of large landowners. In the twentieth century, Hindus from India have migrated to the West for education. From the first days of the diaspora, groups of Hindus have cohered to transfer their faith and practices from native India to their new homes, temples, and communities. Thus, the dissemination of Hinduism around the world has followed two main routes: the route of scholarship and study, as the religion has been studied by non-Indians and introduced to non-Indian populations; and the route of immigration, as devoted Hindus have created Hindu homes and institutions in their places of resettlement.

The acceptance of Hindu ideals and practices in the West has depended upon a succession of Hindu practitioners who visited the West. Beginning with P.C. Moozumdar and Swami Vivekananda at the World Parliament of Religion in Chicago in 1893 and continuing through the residence of Paramahansa Yogananda in the United States beginning in the 1920s, the West has received ever-larger numbers of Hindu teachers, as immigration laws have allowed immigration and free movement in the West (Klostermaier 2007:420-25).

Philosophical and theological ideas from Hinduism have been incorporated into Western thought on a large scale, primarily through the publications and activities of the Theosophical Society and the teachings of many Hindu adepts in the West. Today, every major form of Hindu practice and belief has its Western form, which, although modified from traditional Hinduism, nevertheless, contains the character of Hinduism.

BELIEFS/DOCTRINES

For at least two reasons the Hindu tradition contains the greatest diversity of any world tradition. Firstly, Hinduism spans the longest stretch of time of any major world religion, with even the more conservative views setting it as some 3,000 years old. Throughout this enormous expanse of time, the Hindu tradition has been extremely conservative about abandoning elements that have been historically superseded. Instead, these elements have often been preserved and given new importance, resulting in historical layers of considerable diversity within the tradition. Secondly, Hinduism has organically absorbed as many as 80,000 separate cultural traditions, expressed in as many as 300 languages. As a result, Hindu tradition looks like the Grand Canyon gorge, where every layer throughout history is visible as the great river of time has sliced through the landscape.

The religion of the Rig Veda has for a long time been referred to as henotheistic, meaning that the religion was polytheistic, but it recognized each divinity in turn as, in certain ways, supreme (Hawley and Narayanan 2006:211-12). Certainly, later Hinduism continued and enriched this henotheistic concept, and, through time Hinduism has been able to accept even Christ and Allah as being supreme “in turn.” The Rig Veda , though, was the central text in a very powerful ritual tradition. Rituals public and private, with sacred fire always a central feature, were performed to speak to and beseech the divinities (Thapar 2004:126-30). Sacrifices of animals were a regular feature of the larger public rites of the Vedic tradition (Urban 2010:57).

Modern Hinduism encompasses a wide range of beliefs, which include panentheism, monism, and even forms of monotheism. Most Hindus espouse belief in the authority of the Vedas, Upanishads, and other sacred texts, such as the Mahabharata, Ramayana, and various Puranas that explore the mythological origins of important deities and define social, moral, and religious standards. Hindus typically believe in reincarnation, and hold the goal of faith and religious practice (sadhana) to be mukti or moksha. This means liberation from the cycle of rebirth through a permanent, non-intellectual realization of the inherent unity of one’s individual soul (atman) with Infinite Being (brahman) (Hawley and Narayanan 2006:12).

The henotheistic approach of Hinduism means that, while there are orthodox movements within it, it is also rich with heterodoxy, leaving room for a variety of conflicting traditions and beliefs within the same religious family. Historically, the major schools of Hinduism have embraced both dualistic and non-dualistic theological approaches, and modern Vedanta’s non-dualism nevertheless contains many elements of Samkhya’s dualistic theology (White 1996:34). Vaishnava reform movements of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries often sought to reduce or remove ritual tradition altogether in favor of simpler, more egalitarian practices such as chanting of divine names, meditation, and individual prayer. Tantra, the complex mystical tradition, often embraces beliefs and practices that are contrary to orthodox Hinduism (and has sometimes rejected the authority of the Vedas outright) while venerating the same deities and upholding the same goal of personal liberation and belief in the divine unity of all existence (Flood 2006:32-33).

Hinduism also now largely embraces vegetarianism as an expression of the doctrine of non-harm (ahimsa). Vegetarianism is a  central practice for many orthodox Hindus, and its association with Brahmanical caste custom has made it a means of claiming higher caste status for lower caste groups (Fuller 1992:93). However, animal sacrifice and consumption of meat continues to be a major and necessary component of worship for all castes at certain temples throughout India, especially at several important goddess temples in West Bengal, Assam, and Orissa (McDermott 2011:207-10).

central practice for many orthodox Hindus, and its association with Brahmanical caste custom has made it a means of claiming higher caste status for lower caste groups (Fuller 1992:93). However, animal sacrifice and consumption of meat continues to be a major and necessary component of worship for all castes at certain temples throughout India, especially at several important goddess temples in West Bengal, Assam, and Orissa (McDermott 2011:207-10).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Because Hinduism is a vast and diverse tradition, covering several thousand years of development, and influenced as much by larger religious trends as by individual local traditions, it is impossible to discuss all of the rituals, festivals, and rites of passage included under the umbrella of “Hinduism.” However, it is possible to explore major categories of rituals, their purpose and origins, as well as rites of passage and major festivals celebrated throughout India.

Veda is derived from the word, vid, “to know.” A Veda, then, would literally be a compendium of knowledge. In Indian tradition the four Vedas (sometimes collectively referred to as “the Veda”) are the ancient scriptural texts that are considered the foundation for all of Hinduism. The four are the Rig, Sama, Yajur, and Atharva Vedas (Basham 1989:20-29).

A very powerful ritual tradition was central to the Rig Veda, with fire always a central feature. At public and private rituals (yajnas), worshippers spoke to and beseeched the divinities. Animal sacrifices were a regular feature of the larger public rites in the Vedic tradition (Basham 1989:32-35). Yajna is from the Sanskrit root yaj, “to honor a god with oblations.” A yajna is a ritual involving oblations in the Vedic tradition. It may be simply an offering of clarified butter into a fire, or it may involve seventeen priests in an elaborate twelve-day ritual, including the building of a large fire altar as in the Agnichayana. The ritual of the yajna always includes a fire, Sanskrit mantras, and some sort of offering. In the larger public rituals a sacrifice of some animal or animals has been common. The word yajna is frequently translated roughly as “sacrifice” (Hopkins 1971:14-16).

worshippers spoke to and beseeched the divinities. Animal sacrifices were a regular feature of the larger public rites in the Vedic tradition (Basham 1989:32-35). Yajna is from the Sanskrit root yaj, “to honor a god with oblations.” A yajna is a ritual involving oblations in the Vedic tradition. It may be simply an offering of clarified butter into a fire, or it may involve seventeen priests in an elaborate twelve-day ritual, including the building of a large fire altar as in the Agnichayana. The ritual of the yajna always includes a fire, Sanskrit mantras, and some sort of offering. In the larger public rituals a sacrifice of some animal or animals has been common. The word yajna is frequently translated roughly as “sacrifice” (Hopkins 1971:14-16).

Two of the other Vedas, the Yajur and Sama, were based on the Rig Veda. That is, it supplied most of their text, but the words were reorganized for the purposes of the rituals. The Yajur Veda, the Veda of sacrificial formulas, contains the chants that accompanied most of the important ancient rites and has two branches, the Black and the White Yajur Vedas. The Sama Veda, the Veda of sung chants, focuses largely on praise of the god Soma, the personification of a sacred drink imbibed during most rituals that probably had psychedelic properties. Priests of the three Vedas needed to be present for any larger, public ritual (Hopkins 1971:29-30).

The Atharva Veda became part of the greater tradition somewhat later. It consists primarily of spells and charms used to ward off diseases or influence events. This text is considered the source document for Indian medicine (Ayurveda). It also contains a number of cosmogonic hymns that show the development of the notion of divine unity in the tradition. A priest of the Atharva Veda was later included in all public rituals. From that time tradition spoke of four Vedas rather than three (Hopkins 1971:28-29).

Each of the four Vedas is properly divided into two parts, the mantra , or verse portion, and the Brahmana , or explicatory portion. The Brahmanas contained two important subdivisions that were important in the development of later tradition. The first is called the Aranyaka ; this portion of the text apparently pertained to activity in the forest (aranya). The Aranyakas contain evidence of an esoteric version of Vedic ritual practice ( yajna ) that was done by adepts internally. They would essentially perform the ritual mentally, as though it were being done in their own body and being. This practice was not unprecedented, since the priests of the Atharva Veda, though present at all public rituals, perform their role mentally and do not chant. However, the esoteric Aranyaka rituals were performed only internally. From this we can see the development of the notion that the adept himself was yajna (Kaelber 1989:8).

The Upanishads, a second subdivision within the Brahmanas, were the last of the Vedic subdivisions, commonly found within the Aranyakas. Many of these texts, as did the Brahmanas in general, contained significant material reflecting on the nature of the Vedic sacrifice. In fact, the divisions among Brahmana proper, Aranyaka, and Upanishad are not always clear. The most important feature of the Upanishads was the emergence of a clear understanding of the identity between the individual self (jivan), the greater SELF (atman), and the all-encompassing Brahman , now understood as the totality of universal reality, both manifest and unmanifest (Heehs 2002:57-59).

The genesis of this Upanishadic view that the self was in unity with cosmic reality can be clearly traced. Firstly, Shatapatha Brahmana explained that the most perfect ritual was to be equated to the universe itself. More accurately it was the universe, visible and invisible (White 1996:32). Second, the Aranyakas began to make clear that the initiated practitioner was to be equated to the ritual itself. So, if the ritual equals all reality, and the individual adept equals the ritual, one easily arrives at the idea that the individual equals all reality. The Upanishads, then, were the outgrowth not of philosophical speculation, but of self-conscious ritual practice. The later orthodox Upanishads (those physically associated with a Vedic collection) barely mention the rituals; they merely state the derived abstract concepts.

Worship (puja) is perhaps the central ceremonial practice of Hinduism. A puja minimally entails an offering and some mantras. It can take place at any site where worship can occur, either of a divinity, a guru, or swami, a being, a person (such as a wife, husband, brother, or sister), or spirit. It can take place in a home or a temple, or at a tree, river, or any other place understood to be sacred (Hawley and Narayanan 2006:13).

Incense, fruit, flowers, leaves, water, and sweets are the most common offerings in the puja. Also common is the waving of a  lighted lamp ( arati ). The most elaborate puja, the temple puja before the icon, includes the following elements accompanied by the appropriate mantras (usually in Sanskrit): invitation to the deity, offering of a seat to the divinity; greeting of the divinity; washing of the feet of the divinity; rinsing of its mouth and hands; offering of water or a honey mixture; pouring of water upon it; putting of clothing upon it (if it has not been already clothed for the day); giving of perfume, flowers, incense, lamps, or food; prostration; and taking of leave.

lighted lamp ( arati ). The most elaborate puja, the temple puja before the icon, includes the following elements accompanied by the appropriate mantras (usually in Sanskrit): invitation to the deity, offering of a seat to the divinity; greeting of the divinity; washing of the feet of the divinity; rinsing of its mouth and hands; offering of water or a honey mixture; pouring of water upon it; putting of clothing upon it (if it has not been already clothed for the day); giving of perfume, flowers, incense, lamps, or food; prostration; and taking of leave.

In temples the iconic image of the divinity is always treated as a person of royalty would be treated. Therefore, a puja will be done in early morning accompanied by songs to awaken the deity. The deity is then bathed, dressed, and fed, and then more fully worshipped. Pujas go on throughout the day to the deity, as local traditions require (Fuller 1992:66-69).

Another common form of worship is the homa, havan, or yajna, a modern form of the Vedic yajna that mirrors much of the Vedic ritual, but adapts it to modern worship. Oblations of ghee, flowers, sacred grass, herbs, fruits, and other special items as required are offered to the fire, venerating a particular deity. Offerings are made accompanied by Sanskrit mantras. During the ritual, a priest may offer oblations at the end of each repetition of a particular mantra associated with a specific deity, or at the end of each line of a particular hymn chosen for the ritual. This form of worship may be performed as a stand-alone ritual, or may accompany a puja (Klostermaier 2007:266).

Samskaras (from the Sanskrit samskri, refined, the source of the word Sanskrit) are ritual ceremonies that mark and purify life cycle events. Every samskara requires a Brahmin priest to preside and includes prayers, oblations, offerings, and a fire ritual (Klostermaier 2007:147-49).

Rituals are performed to encourage impregnation and to obtain a male child. A special rite is performed at birth. The annaprashana is usually performed at the sixth month after birth to mark the feeding of the first solid food. The investiture of the sacred thread, the upanayana ceremony, is performed for twice-born (high-caste) Hindu males when they are between ages eight and twelve. There is evidence, however, that in Vedic times this ceremony was performed for both boys and girls (Olivelle 1977:22, n.5).

Perhaps the two most important samskaras for Hindus are the wedding ceremony and the death ceremony (sraddh). The sraddha can be performed only by a male child, though it is now occasionally (and somewhat controversially) performed by daughters. It ensures that a soul does not remain as a ghost but goes on either to liberation or to its next birth. A yearly ritual is performed to feed the deceased, in particular Brahmins, lest they fall from heaven. This ancient ritual of feeding the ancestor seems to conflict with the belief that nearly everyone is reincarnated, and that few proceed directly to heaven (Klostermaier 2007:150-55).

can be performed only by a male child, though it is now occasionally (and somewhat controversially) performed by daughters. It ensures that a soul does not remain as a ghost but goes on either to liberation or to its next birth. A yearly ritual is performed to feed the deceased, in particular Brahmins, lest they fall from heaven. This ancient ritual of feeding the ancestor seems to conflict with the belief that nearly everyone is reincarnated, and that few proceed directly to heaven (Klostermaier 2007:150-55).

Vows (vratas) are a central feature of Hinduism. They are undertaken for myriad reasons, but always with the desire of pleasing the divinity. Vows are often taken to do a particular thing in exchange for help from God. For instance, a mother might promise to donate a sum of money to a certain divinity’s temple, if her gravely ill child should recover. A person might carry out a vow to shave his or her head and make a pilgrimage to a god’s temple in exchange for success on exams or to get a male child (Pearson 1996:5-7).

In times past, very severe vows were sometimes taken. People were known to starve themselves to death in exchange for a divinity’s promise to remove a curse on their family; others vowed that if a son were born they would offer him up to a renunciatory order upon his coming of age. Indian mythology records innumerable severe vows. Ravana the demon king, for instance, took a vow to stand on one toe for 10,000 years in order to win overlordship of the universe (Sutherland 1991:64).

Most vows in modern times involve fasting, celibacy, pilgrimage, study of sacred books, feeding of Brahmins or mendicants, or limited vows of abstention. Vratas can be classified in different ways. One classification divides them into those that are bodily, those that pertain to speech, and those that pertain to the mind. Another type of classification is related to duration and timing of the vow, whether for a day, several years, until the fortnight is over, or until a certain star appears. A third classification is according to the divinity for whom the vow is performed. Last are vows that are specific to certain castes or communities.

To be valid, vows must almost always begin in a condition of ceremonial purity. Most vows begin early in the morning. Festivals, in general, often entail vows taken by various family members; typically they involve fasting, but they may also involve celibacy, service to the divinity, and pilgrimage (Rinehart 2004:86).

There is a long list of special days appropriate to specific vows, usually entailing particular obligations of worship and observances. A devotee might vow to worship the Sun and fast on the day of Acalasaptami; to worship Lakshmi at the base of a tree during Navaratri; to abstain from plowing on Ambuvachi; to abstain from fish on Bakapan- caka; or to bathe three times and make special offerings to the ancestors on Bhismapanchaka. Certain days of the month are auspicious for particular vows. The eleventh of the month is observed as a fast day by many Hindus. The Caturvargacintamani of Hemadri (c. thirteenth century) lists nearly 700 such vows.

Major annual festivals are common throughout India and are typically scheduled according to the lunar calendar, with festivals often occurring on full moon or new moon days. Although some festivals are common throughout India, the specific traditions and worship associated with these festivals vary greatly by region, and even the meaning of the same festival may vary slightly or greatly depending on local customs. There are also many festivals that are specific only to certain regions, and thus important to those local or regional traditions, but not celebrated widely across India.

Festivals may be focused on a particular time of year, such as phases of the harvest or onset of monsoon, or based around particular ritual activities. Such festivals include the annual January harvest festival, called by different names throughout India; examples include Makarsankranti in North India, Pongal in South India, and Bohag Bihu in Assam. The Kumbha Mela is both a  pilgrimage and a massive religious festival, considered the largest gathering of people in the world. Tens of millions of devotees gather in Allahabad every twelve years to bathe at the convergence of the sacred Ganga, Yamuna, and (now-dry) Sarasvati rivers. They also gather to meet other pilgrims and learn from the religious teachings of gurus and sadhus who make encampments there. The Purna Kumbha Mela occurs every twelve years, with the Ardha Kumbha Mela happening every six years, and Maha Kumbha Mela every 144 years.

pilgrimage and a massive religious festival, considered the largest gathering of people in the world. Tens of millions of devotees gather in Allahabad every twelve years to bathe at the convergence of the sacred Ganga, Yamuna, and (now-dry) Sarasvati rivers. They also gather to meet other pilgrims and learn from the religious teachings of gurus and sadhus who make encampments there. The Purna Kumbha Mela occurs every twelve years, with the Ardha Kumbha Mela happening every six years, and Maha Kumbha Mela every 144 years.

Festivals are often focused on a particular deity or set of deities. Saraswati Puja (January) venerates the goddess of learning and the arts, in which students pray for success in studies, and devotees offer their books and musical instruments to the goddess for blessings. During Shivaratri (February), the night of Shiva, devotees throughout India celebrate with fasting, all-night puja and singing, and consumption of bhang, a drink of spiced milk mixed with cannabis, and sweets laced with cannabis. Holi (March) is a two-day festival that honors Krishna, the divine avatar of the deity Vishnu who was quite mischievous as a child. During those two days, caste rules are relaxed, and people of all ages play in the streets and in their homes, dousing each other with brightly colored powders and water. Durga Puja (September/October and March/April) celebrates the goddess Durga and her victory over evil as related in the fifth century Devi Mahatmyam, which is recited daily by many devotees during the festival. The autumn Durga Puja coincides with Ramlila celebrations in North India, which reenact stories from the Ramayana, specifically the legendary victory of Lord Rama, another beloved avatar of Vishnu, over the demon Ravana. Divali (October/November) is celebrated in some parts of India primarily as a festival of Lakshmi, the goddess of harvest, home, and wealth. In other areas, particularly Assam and West Bengal, it is called Kali Puja and is devoted to Kali, the fierce mother goddess of liberation.

Aside from these and more pan-Indian festivals, specific temples, pilgrimage centers, cities, and villages each have their own locally important festival days that draw hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of visitors. In Assam, the festival of Ambuvachi (June) commemorates the annual menstruation of the earth at the Kamakhya temple in Guwahati. At the Nataraja Shiva temple in Chidambaram, Tamil Nadu, the Arudra Darshan (January) festival celebrates Shiva’s cosmic dance. At the Jagannath Temple in Puri, Orissa, the Rath Yatra (July) features immense chariots or cars, constructed and brilliantly painted by hand. Millions attend the festival with the hope of seeing the deities and their cars, which must be pulled by hand by hundreds of men. The cars carry the deities of the temple, Jagannath (Krishna), his brother Balaram and sister Subhadra, down the main boulevard in front of the temple for a seven-day outing. Because low-caste Hindus and foreigners are barred from entering the temple, this festival represents a rare opportunity to see the deities, though the murtis that ride in the cars are actually copies of the murtis residing inside the temple.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Hinduism represents an exceptionally diverse collection of various regional religious traditions, and as such

it has no central organization or authority figure. Although some conservative political movements have promoted a kind of orthodox, unified Hinduism, historically it is incredibly diverse in belief and practice. (Nicholson 2010:3-4) It has survived millennia through evolution and diversification, acceptance and incorporation of various regional beliefs, deities, and practices through gradual processes of overt and subtle cultural and religious negotiation, and eventual incorporation. (Flood 1996:16) From region to region, these beliefs and practices may even find themselves in direct conflict with each other on fundamental levels, yet all is considered Hindu, and divergent groups may share some core philosophical ideals or religious texts, even if they interpret them very differently. There is no central authority dictating what is or is not “Hindu.” While individual groups may have specific beliefs that are considered “orthodox,” either according to the religious rules of their particular group or to “Hinduism” as a whole, the definition of what is considered orthodox has never been fully standardized, has shifted over time, and will continue to change as Hinduism finds its way to different places around the world and meets new technology and ideas. These standards and practices may shift from region to region, temple to temple, and person to person. For example, there are some temples that condone and even require animal sacrifice and the consumption of meat by all castes, including Brahmins, as in northeast and eastern India. Others find this practice abhorrent and totally inconsistent with a Hindu philosophy. Both are correct and fully “Hindu” (Fuller 1992:83-84).

it has no central organization or authority figure. Although some conservative political movements have promoted a kind of orthodox, unified Hinduism, historically it is incredibly diverse in belief and practice. (Nicholson 2010:3-4) It has survived millennia through evolution and diversification, acceptance and incorporation of various regional beliefs, deities, and practices through gradual processes of overt and subtle cultural and religious negotiation, and eventual incorporation. (Flood 1996:16) From region to region, these beliefs and practices may even find themselves in direct conflict with each other on fundamental levels, yet all is considered Hindu, and divergent groups may share some core philosophical ideals or religious texts, even if they interpret them very differently. There is no central authority dictating what is or is not “Hindu.” While individual groups may have specific beliefs that are considered “orthodox,” either according to the religious rules of their particular group or to “Hinduism” as a whole, the definition of what is considered orthodox has never been fully standardized, has shifted over time, and will continue to change as Hinduism finds its way to different places around the world and meets new technology and ideas. These standards and practices may shift from region to region, temple to temple, and person to person. For example, there are some temples that condone and even require animal sacrifice and the consumption of meat by all castes, including Brahmins, as in northeast and eastern India. Others find this practice abhorrent and totally inconsistent with a Hindu philosophy. Both are correct and fully “Hindu” (Fuller 1992:83-84).

Thus, although the Vedas, Upanishads, the Mahabharata and Ramayana, and the Puranas are considered by the majority of Hindus to be essential texts for religious doctrine, there is also a rich tradition of dissent and debate regarding spiritual belief, religious practice, and social organization within the religion. This is represented in traditions such as Tantrism, Lingayatism, ISKCON (International Society for Krishna Consciousness), and many others that maintain some core beliefs that are in alignment with what may broadly be considered “Hindu,” though in practice and philosophy many of their ideas may rebel against the social or spiritual rules laid out in some of the most common scriptures, favoring other scriptures or producing new ones based on fresh revelation.

Although Hinduism lacks a central authority figure and organization, there are basic organizing principles that remain similar from  group to group. Most Hindus perform worship in their homes, and also participate in temple worship. Temples can serve as a social and spiritual hub for local communities, and some larger temples attract thousands or even millions of devotees from around the world during major festivals. Another important organizing principle is the relationship of guru and disciple, which is at the center of lineage traditions. The concept of the guru, whether the guru is formal or informal, is also at the heart of Hinduism in all its many forms, and is essential for transmission of belief and practice from generation to generation.

group to group. Most Hindus perform worship in their homes, and also participate in temple worship. Temples can serve as a social and spiritual hub for local communities, and some larger temples attract thousands or even millions of devotees from around the world during major festivals. Another important organizing principle is the relationship of guru and disciple, which is at the center of lineage traditions. The concept of the guru, whether the guru is formal or informal, is also at the heart of Hinduism in all its many forms, and is essential for transmission of belief and practice from generation to generation.

The Sanskrit word guru (“weighty” or “heavy” or “master”) is said to derive from gu (the darkness of ignorance) and ru (driving away)—thus, “the one who drives away the darkness of ignorance.” (Gupta 1994) The notion of the guru began in Vedic times; a student would live with a master for 12 years to acquire the Vedic learning. He treated the guru as his father and served his household as well. Today, a guru is a person’s spiritual father or mother, who is entitled to special deference, as are the guru’s spouse and children. A guru is typically male, especially in more orthodox traditions, but there have also been prominent female gurus throughout the history of Hinduism (Pechilis 2004:3-8).

The guru is a spiritual guide, and typically teaches a particular set of practices as well as confers diksha (initiation) to disciples, inducting them into a particular parampara (unbroken lineage tradition). The parampara is a succession of gurus and disciples that is passed down generation to generation, and may be quite linear, in which there is a central guru who chooses his or her successor before their death, or may form branches, in which case the guru empowers several disciples to pass on the teachings and lineage by initiating others. Some traditions feature a mixture of these elements, in which only certain families are empowered to pass on the lineage, and in which senior disciples may teach practices and philosophy to fellow initiates, but may not initiate others themselves (Saraswati 2001:4).

Almost all traditions understand that spiritual progress and liberation from birth and rebirth cannot occur without the aid of a guru. In many contemporary Indian traditions the guru is seen to be God himself (or Goddess herself) and is treated as such; thus, a guru’s disciples may often refer to their devotion to the “feet of the guru” or their fealty to the “sandals [ paduka ]” of the guru. (Touching of the feet in India is a sign of deep respect.) So important is the guru that every year a holiday, Gurupurnima, is celebrated. It takes place on the full Moon in the lunar month of Ashadha (June–July). It was dedicated originally to the sage Vyasa, who compiled the Vedas and the Mahabharata, but it is observed by worship or honoring of one’s teachers and gurus (Gupta 1994).

The temple is the center of Hindu worship. It can vary in size from a small shrine with a simple thatched roof to vast complexes of stone and masonry. During most times of the year the temple is devoted to individual or family worship or to greeting of the divinity. Since many houses in India have their own shrines set up for worship, the temple is reserved for special worship or for requests to the divinity, often by people who have made pilgrimages. At festival times temples are given over to group worship, as devotees sing bhajans or kirtans (types of religious songs) or to various rituals that commemorate special events in the life of the divinity, for example, the marriage of Minakshi at the Meenakshi Temple in Madurai.

The early worship of the Vedas took the form of a ceremony around a fire or fires, without any permanent structures or icons. Location was unimportant. As Hinduism developed, it borrowed from other modes of worship, and both location and iconography became central features (Mitchell 1988:16). Often geography determined temple location: high places that jut out from the countryside would usually have at least small temples at their summits, as would river junctions. In addition, places traditionally associated with events in the lives of a deity would often be marked with temples. The temple at Rameshvaram, for example, marks the place where Rama had his monkey armies build a bridge to cross over and fight the demon king Ravana, according to the Ramayana (Lutgendorf 2007:206).

Today, icon worship is central to Indian temple worship (Eck 1998:10). The stone or metal image itself is not worshipped. The icon is merely the place the divinity inhabits. A complex ritual must first be performed to install the divinity in the image. Thereafter, the image is treated as the divinity itself would be: it is bathed, dressed, sung to, fed, and feted each day. For Shaivites, most often the icon is the Shiva Lingam, the erect phallus symbol of Shiva surrounded by the round yoni representing the goddess’s sexual organ. For Vaishnavites the icon is a full representation of Vishnu in one of his forms; for Shaktas it is an image of the great Goddess.

Often the inner sanctum of the temple, its most holy spot, holds a small, typically modest icon. The more elaborate statues and images are usually located in the larger temple precincts. Large temples often boast a huge array of images of gods and goddesses, usually depicting a particular event in their story. One might see, for instance, Narasimha, the man-lion avatar of Vishnu, ripping apart his demon foe Hiranyakashipu, or see Shiva in his pose as the divine dancer, Nataraja.

Puja, the regular worship service including offerings and rites, is usually performed before the central icon at fixed times during the day. For a donation, devotees can dedicate certain features of a regular puja, such as the recitation of a particular mantra. They may also pay for pujas to be conducted by Brahmin priests at other times, simple or elaborate at their discretion, in support of certain prayers or pleas to the divinity. A woman might want to have a son, a man might want to gain success in business, or a student might seek success in exams. All worldly and salvational requests are taken to the divinity of the temple; popular temples are thronged with people year round. (Fuller 1992: 62-63).

The puja consists, at the minimum, of fruit, water, and flower offerings to the divinity, accompanied by the appropriate mantras. This is followed by arati , or waving of a lighted lamp before the divinity while ringing a bell, which may also be accompanied by other formal offerings such as flowers, clothing, fan, food, and drink. At the end of the ritual people may step forward and waft the light and smoke from the lamp over their head or face to receive the blessing of the divinity. In many temples one may receive a little of the food that had been offered to the divinity, called prasada, which will confer blessing when eaten (Fuller 1992:57).

This is followed by arati , or waving of a lighted lamp before the divinity while ringing a bell, which may also be accompanied by other formal offerings such as flowers, clothing, fan, food, and drink. At the end of the ritual people may step forward and waft the light and smoke from the lamp over their head or face to receive the blessing of the divinity. In many temples one may receive a little of the food that had been offered to the divinity, called prasada, which will confer blessing when eaten (Fuller 1992:57).

Most temples in India, including all of the well-known temples, allow only Brahmins to perform the rituals. There are smaller and larger shrines all over the country, however, which have non-Brahmin and even Shudra (low-caste) priests (Shah 2004:38). These are usually temples serving a smaller local community. By law, any member of any caste may enter any temple in India. Nevertheless, in practice Dalits (untouchables) are often barred. Certain temples admit only Hindus; Muslims and Christians will be excluded if they are identified. In some areas non-Indians are excluded as a rule, unless they can produce paperwork to prove their conversion (some temples will bar entrance to them anyway). A famous case of temple exclusion took place when Indira Gandhi, prime minister of India, visited the Jagannath temple at Puri. She was excluded because she was married to a non-Hindu.

Many great Hindu temples deserve mention: the Vishvanatha Temple to Shiva in the holy city Benares (Varanasi); the famous Kali temple at Kali Ghat in Calcutta (Kolkata); the Jagannath Temple to Krishna in Puri; the temple for the goddess Kamakshi at Kanchipuram; the Brihadishvara Temple to Shiva in Tanjore; the Meenakshi Temple to the goddess Minakshi and the Shrirangam temple to Vishnu, both in Tamil Nadu.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Throughout its long history, Hinduism has faced various challenges from without and within. Islam, Buddhism, Jainism, and Christianity have competed with Hinduism for centuries, and their rejection of caste has made them more popular amongst groups disadvantaged in the traditional Hindu hierarchy. Hindu nationalism as a modern movement has sought to redefine Hinduism as a strictly orthodox, monolithic identity that falls closely in line with Brahminical ideals. Meanwhile, issues of gender and caste present theological challenges to orthodoxy that often enliven heterodox traditions and promote pluralism.