PEOPLE LOVE PEOPLE HOUSE OF GOD

PEOPLE LOVE PEOPLE HOUSE OF GOD TIMELINE

1924 (January 22): Albert Wagner was born in Crittenden County, Arkansas.

1937: Wagner was forced to work to provide for his brothers and mother.

1941: Wagner moved to Cleveland where he would live for the rest of his life.

1942: Wagner met the love of his life, Magnolia, started a family, and founded a furniture moving company.

1962: Magnolia left Albert after discovering Albert’s infidelity.

1974: Wagner had a revelation in his basement, turning him from his sinful ways to a lifetime of salvation through his artwork.

1980: Wagner moved into the house that would become the centerfold of his ministry now known as The People Love People House of God.

1998: The Fruit Avenue Gallery in Cleveland, Ohio hosted Wagner’s largest outsider art show.

2006: Wagner died after completing over 3,000 paintings and sculptures during his 32-year career.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

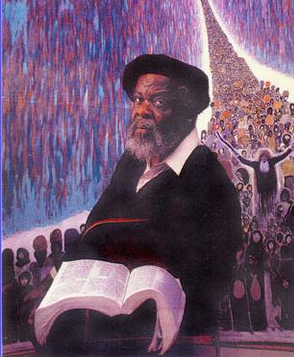

Albert Wagner was born on January 22, 1924 in Crittenden County, Arkansas. Wagner exhibited an artistic inclination at an early  age but was forced to work when he turned thirteen in order to provide for his three brothers and his mother. He was only educated through the second grade. Wagner’s mother was deeply religious, and provided the early religious framework for Wagner’s beliefs. When Wagner was seventeen, as the head of the household, he moved his family to Cleveland to find work. Soon after, in 1942, Wagner married “the love of his life,” Magnolia, and simultaneously began a family and a furniture moving business (Miller 2008).

age but was forced to work when he turned thirteen in order to provide for his three brothers and his mother. He was only educated through the second grade. Wagner’s mother was deeply religious, and provided the early religious framework for Wagner’s beliefs. When Wagner was seventeen, as the head of the household, he moved his family to Cleveland to find work. Soon after, in 1942, Wagner married “the love of his life,” Magnolia, and simultaneously began a family and a furniture moving business (Miller 2008).

Over the course of the next fifteen years of Wagner’s life, he moved away from the religious beliefs of his mother and became addicted to “worldly things.” In Wagner’s words, “Sex had me bound and chained. I was like the Wolfman. The moment that trick of lust allured my nostrils, it was like I had fangs. My body went to the beast.” His lustful inclinations led to his infidelity and ultimately caused Magnolia to leave him in 1962. Over the course of this time, Wagner was supporting three families and twenty children, fifteen of whom were with his wife, Magnolia, prior to her departure (Kangas 2008).

The absence of his wife of twenty years sent Albert into a downward spiral, which would be reversed on the night of his fiftieth birthday. Wagner provides his own account of this night saying, “I was preparing for my party and I go into the basement. There was this old board on the floor with drips of paint on it. That old hunk of wood just started talkin’ to me.” This old hunk of wood, Albert claims, spoke to him, telling him that painting and art would provide a pathway to salvation. Thus began Albert Wagner’s lifelong art ministry. His first painting, which he began on that same night, was called “Miracle at Midnight” attesting to his revelation and return to his own version of his religious past. In one night, Wagner transformed from a successful businessman, juggling three identities and families, to a devoted minister, father, and artist (Miller 2008).

After Wagner’s revelation, he went on to become an ordained minister and devoted the remainder of his life to painting, family, and his art ministry. In his own words, “All of my life I wanted to paint, I just didn’t know how. God gives directions and you have to follow them.” The house he moved into in Cleveland in 1980 transformed from a typically furnished house to a living area completely dominated by his artwork. His art became both his own autobiography and a means to teach and save others through his own version of salvation. And his house, dubbed People Love People House of God, became the epicenter of his folk art ministry.

By the time of his death in September, 2006, Albert had completed over 5,000 paintings. His art is eclectic, ranging from images of African Queens, lynching in the old South, murder of Native Americans, the crucifixion of Christ, and the suffering of African Americans. His art exhibits a blend of historical interpretation and his own experiences (Cohn 1998:80). Albert Wagner has art  displayed in the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland and much of the rest of his art is still preserved at the Albert Wagner Museum in the Creekside Art Gallery located in Concord, Ohio. The Kangas family, lifelong friends of Wagne, preserves this gallery and also put together a biography of Albert titled Water Boy: The Art and Life of Albert Lee Wagner (Kangas 2008).

displayed in the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland and much of the rest of his art is still preserved at the Albert Wagner Museum in the Creekside Art Gallery located in Concord, Ohio. The Kangas family, lifelong friends of Wagne, preserves this gallery and also put together a biography of Albert titled Water Boy: The Art and Life of Albert Lee Wagner (Kangas 2008).

DOCTRINE/BELIEFS

After his conversion, Albert Wagner, like his religious mother, professed to be a non-denominational Christian and recognized Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior. He became an ordained minister from the denomination called the “Commandment Keepers.” Wagner focused his entire life on making up for his past “worldly” actions through his art and ministry. Wagner keeps Kosher, observes the Sabbath from Friday night until sundown on Saturday, and focuses his ministry around “solutions to what he sees as the plight of the Black man.” In fact, much of his ministry is filled with racial undertones that have alienated a significant portion of the African American community. Throughout his art, Wagner “accuses the Black community of self-oppression, a disregard of responsibility, and weakness for sexual gratification” (Miller 2008).

In his own words, Albert claims, “We [the Black man] need to see the true root of all our troubles. The fault does not lie in American history, not in slavery times or any other injustice, but way back in antiquity. Ethiopia sinned; it’s in the Bible. We committed atrocities in God’s eyes. And this is my mission now, to make my people fall down on their knees and beg his forgiveness.” Furthermore, Wagner believed “the black man has a sexual sickness, more than any other people in the world.” In his work titled “American History,” the lynching of a black man is portrayed but rather than aiming such a provocative piece at that white perpetrators, he directs the caption toward the African American community: “We must not let what happened then erase us of the reality of today” (Leland 2001).

As a result of his comments and critiques of the African American community, he has received overwhelming support from white patrons and collectors while being, for the most part, rejected by the African American community. In response to this reaction, Wagner said, “I have so much I want to give to my people, but they don’t accept it. They don’t like me because of what I’m saying. I’m an Uncle Tom. Everyone’s an Uncle Tom who tells us to get up and make something of ourselves.” This sentiment, has led to his own personal allusion to Moses (exhibited in the most significant painting in the People Love People House of God) a fourteen-foot canvas of Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt. While Wagner refrains from proclaiming prophetic inspiration, he alludes to Mosaic inspiration in his art and ministry. Wagner said, “Maybe somehow the Lord has permitted me to feel the joy or the pain that Moses felt, so I’m able to express his thoughts” (Leland 2001).

Overall, Wagner desired to save those who are lost and engaging in “worldly” temptations, like he was, through his art and ministry at the People Love People House of God. He focused explicitly on the African American community, preaching his message of empowerment, saying, “I cannot erase history, but history is erasing us. We’re using history as an excuse” (Leland 2001).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The People Love People House of God was kept open to the public throughout Wagner’s ministry. It is a three-story house about  fifteen minutes East of downtown Cleveland. Also known as the Wagner Museum, the People Love People House of God held services every Saturday for the duration of the day. The congregation was mostly made up of his family members and local neighbors, although his services could grow to be close to one hundred people engaging in singing, testimonial, and preaching. Although Wagener tended to refrain from calling himself a prophet, he justified the African American community’s dismissal of his teachings by stating, “Every prophet is crazy to most people. If he wasn’t, there would be no need to prophesy” (Miller 2008).

fifteen minutes East of downtown Cleveland. Also known as the Wagner Museum, the People Love People House of God held services every Saturday for the duration of the day. The congregation was mostly made up of his family members and local neighbors, although his services could grow to be close to one hundred people engaging in singing, testimonial, and preaching. Although Wagener tended to refrain from calling himself a prophet, he justified the African American community’s dismissal of his teachings by stating, “Every prophet is crazy to most people. If he wasn’t, there would be no need to prophesy” (Miller 2008).

Wagner’s ministry and art was idiosyncratic, blending his religious beliefs, personal experiences, and goals throughout. Before his death, Wagner recounted his life, work, and ministry by reminiscing, “All of these years have passed since I was that little boy on my mother’s back porch, and now I realize that all I wanted to do is paint. I’m not trying to make myself different from anybody, but God made me what I am, and it is important to me to introduce to the black world, my little black sisters and brothers, that you can take an old television, and an old stove, anything you want, and make a sculpture of it. Even the bottom of an old dresser drawer, a door or a window. At first, I thought I had nothing to work with, but then I found that everything I wanted was in the street or the alleys. Everything in here is made up of Elmer’s glue, good will, gifts from people and the streets. So now I have a whole museum to show the world” (Miller 2008). Rev. Wagner sought to maintain an aura of hospitality for his Cleveland community and did so by keeping his house open for all to enter. Although the doors of the Wagner house are now closed, his ministry, art, and life is preserved by his lifelong friends, the Kangas family, at the Creekside Art Gallery in Concord, Ohio (Kangas 2008).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

While it is difficult to concretely define the rituals and practices of Albert Wagner’s People Love People House of God, there are a few important components of his religious practice. Wagner commited to keeping Kosher and observed the Sabbath from Friday night to Saturday at sundown. On Sundays, the People Love People House of God was open to services all day and Wagner invited all to participate in his unique vision of worship through painting (Miller 2008). Rev. Wagner refused to participate in any pagan holidays and focused his preaching on empowering all, through his art and experience, to avoid sin and depravity.

ISSUES/CONTROVERSIES

Reverend Wagner was a controversial character, although general public outcry at his comments or religious enthusiasm was rare. He often alienated the African-American community through his explicit condemnation of “the black man” stemming from his early experience and depravity (Leland 2001). Much of his rhetoric was pointed and scathing, for example, Wagner stated, “I believe the black man has a sexual sickness, more than any other people in the world” (Leland 2001). He was at various times called an “Uncle Tom,” and responded to such accusations by saying, “I have so much I want to give to my people, but they don’t accept it. They don’t like me because of what I’m saying. I’m an Uncle Tom. Everyone’s an Uncle Tom who tells us to get up and make something of ourselves” (Leland 2001). Overall, Wagner’s acceptance by the white community and condemnation of African-American actions was a controversial part of his aim to save the world from depravity through his art.

He often alienated the African-American community through his explicit condemnation of “the black man” stemming from his early experience and depravity (Leland 2001). Much of his rhetoric was pointed and scathing, for example, Wagner stated, “I believe the black man has a sexual sickness, more than any other people in the world” (Leland 2001). He was at various times called an “Uncle Tom,” and responded to such accusations by saying, “I have so much I want to give to my people, but they don’t accept it. They don’t like me because of what I’m saying. I’m an Uncle Tom. Everyone’s an Uncle Tom who tells us to get up and make something of ourselves” (Leland 2001). Overall, Wagner’s acceptance by the white community and condemnation of African-American actions was a controversial part of his aim to save the world from depravity through his art.

REFERENCES

Beal, Timothy. 2008. Religion in America: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cohn, Nik. 1998. “Faith in Paint.” Life Magazine (May):79-80.

Kangas, Gene and Linda Kangas, eds. 2008. Water Boy: The Art and Life of Reverend Albert Lee Wagner . DVD.

Leland, John. 2001. “At Home with the Rev. Albert Wagner; Moses of East Cleveland, with Detours.” The New York Times (January 25).

Miller, Thomas (Director). 2008. One Bad Cat: The Albert Wagner Story. DVD.

Ritchey, Debbie. 1996. “Objects from the Alley: The Work of Rev. Albert Wagner.” Journal of the Folk Art Society of America 9:1-4.

Author:

Eric Pellish

Post Date:

4 February 2014