ASATRU TIMELINE

870-930 CE: Norse Pagan Vikings settled in Iceland.

930-1262: Iceland was established as an independent republic or commonwealth, with a national parliament, the Alþingi (the “All-Thing” or “Thing-of all”).

1000: The Alþingi voted to accept Christianity as the official religion of the country, while allowing Pagan religious practices to continue in private.

1100-1300: Myths and poems concerning the now-fading Pagan traditions were preserved in literary texts called Eddas and Sagas.

1262-1944: Iceland comes under Norwegian (then Danish) rule, suffering exploitation as a colonial state. Religious life was dominated first by the Catholic Church, then the Lutheran. Pagan traditions survived in folklore. Icelandic nationalists pushing for independence in the nineteenth century praised Icelandic medieval literature with its tales of Pagan gods and forebears as essential national heritage.

1944 to 2020: Iceland’s declaration of an independent republic was accepted by its long-time colonial overlord, Denmark, on June 17. The new nation-state followed the Nordic social democratic model to become a prosperous country by the 1970s.

Late 1960s: A group led by poet Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson began forming Ásatrúarfélagið (the Ásatrú Society or Fellowship) as an organization dedicated to Iceland’s pre-Christian religious and cultural traditions.

1972-1973: The Ministry of Religious Affairs granted Ásatrúarfélagið recognition as a state-supported religious organization. Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson was elected to lead the Society as its first Allsherjargoði (high priest).

1972-1992: Beginning with less than 100 members, Ásatrúarfélagið became an accepted part of Icelandic society.

1993 (December 24): Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson died. His funeral is broadcast on national television, sparking new growth in membership.

1993-2002: Jormundur Ingi Hansen served as Allsherjargoði. Membership reached 280 in 2000.

2000: Ásatrúarfélagið was granted the right to perform Pagan rituals at Þingvellir, the historic site of the Alþingi, over the opposition of the Icelandic National Church.

2002: Jormundur Ingi Hansen stepped down as Allsherjargoði, with Jónína K. Berg serving as interim Allsherjargoði.

2015: Plans were finalized for a temple complex in Reykjavík and construction commenced.

2003-2020: Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson was elected Allsherjargoði. Membership grew from 879 in 2005 to 4,473 in 2019.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Myths, legends and poems of Norse Paganism have been better preserved in Old Icelandic (Old Norse) literature and folklore than anywhere else in Europe. The most important Norse Pagan texts are the collection of Old Norse poems on mythological and heroic themes known as the Elder or Poetic Edda. These are an extensive commentary on the Eddic poems by Snorri Sturluson (1179-1241) alternately known as the Prose Edda or the Snorra Edda, and partially historical, partially fictionalized narratives of the early Icelanders known as Sagas.

Iceland, a Pagan majority country in its earliest history, converted to Christianity by parliamentary vote in the year 1000, under heavy political pressure from King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway. Though the worship of Pagan Norse gods like Óðinn (Odin), Þór (Thor) and Freyja fell away, Pagan traditions such as worship of elves, land-spirits and invisible huldufolk (“hidden people”) lived on, coexisting with the newer Christian traditions and ultimately blending with them. The old tales and poems steeped in Norse Paganism were read and recited along with selections from the Bible and legends of Christian saints as forms of entertainment and inspiration during the long, hard winters of colonial domination. The nineteenth century national independence movement brought new attention to the Pagan dimension of Iceland’s cultural heritage. The achievement of full political independence in 1944, followed by growing prosperity and national pride, paved the way for a modern rebirth of Icelandic Paganism.

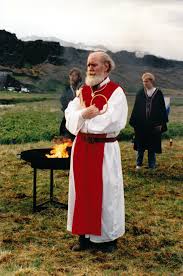

Ásatrúarfélagið (literally, the “Ása Faith Fellowship;” more simply, the “Ásatrú Society”) began to develop in the late 1960s a group of Icelander led by the poet Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson (1924-1993) [Image at right] as an organization that they hoped would not merely honor the traces of Norse Paganism embedded in Icelandic literature and culture, but to revive and refashion this religion for modern life. The artistic and literary inclinations of the founding group have greatly influenced the character and activities of the Society.

In 1973, after lengthy negotiations and over the objections of the Icelandic National Church, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Iceland, the Ministry of Religious Affairs granted Ásatrúarfélagið recognition as a state-supported religious organization. At one point in the discussions, a massive thunderstorm plunged Reykjavík into darkness after a spectacular lighting strike, which some humorously interpreted as a pro-Ásatrú message from the thunder-god Thor. Ásatrúarfélagið now became eligible for public funding through a religion tax paid by Icelanders and was granted full legal authority to conduct rituals such as weddings and funerals.

Sveinbjörn was elected Ásatrúfélagið’s first Allsherjargoði (high priest) in 1973 and would remain in this role for two decades. A farmer and poet devoted to traditional Icelandic culture, Sveinbjörn personified the Icelandic past while also being able to reach out to the young, sometimes taking to the stage in the 1980s to chant medieval rímur poetry to punk rock accompaniment. With piercing blue eyes, long white beard, pipe in hand and priestly white and red robes worn on ceremonial occasions, Sveinbjörn was something of a Pagan Santa Claus for Icelanders, making him an effective spokesperson for the new-old religion of Ásatrú in Iceland.

In Sveinbjörn’s time as Allsherjargoði, the Ásatrú Society developed regular structures and procedures with an elected board of governors, regular board meetings, officers with designated ranks and functions, seasonal ritual gatherings known as Blóts, and life-cycle rituals roughly parallel to Christian baptism, confirmation, marriage and funeral rites.

Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson died on December 24, 1993. His funeral, broadcast on national Icelandic television, contained Christian as well as Pagan elements, with a Christian minister, a close friend of Sveinbjörn, reading from the Bible, and Sveinbjörn’s friend and successor as Allsherjargoði, Jormundur Ingi Hansen (1940- ), [Image at right] reading from the Eddic poem Voluspá (“The Speech of the Seeress”), and a church choir singing traditional Icelandic songs. The funeral service was performed in the church adjoining the graveyard where Sveinbjörn was laid to rest. In contrast to the usual Icelandic Christian custom that has the dead buried with the Book of Psalms, Sveinbjörn was laid into the ground with a drinking horn used at Blót rituals, two Þór (Thor) hammer pendants, and the Eddic poem Hávamál (“The Teachings of the High One”, i.e., Óðinn [Odin]), as well as a book of Icelandic poems and a favorite pipe.

Sveinbjörn’s mixed-faith funeral expressed a relaxed, ecumenical and non-dogmatic attitude about religious identity that may have helped allay any suspicion that Ásatrúarfélagið was a dangerous “cult.” Membership grew markedly after the highly publicized funeral and has continued on an upward trajectory to the present time (2020).

Jormundur Ingi Hansen was a gifted orator with a flair for the theatrical and a deep knowledge of Icelandic Pagan traditions. More international in outlook than Sveinbjörn, Jormundur pursued communications with emerging Pagan movements in other countries and took part in meetings of the World Congress of Ethnic Religions (WCER), founded by the late Jonas Trinkūnas (1940-2014), leader of the Lithuanian Romuva Pagan revival movement. As some groups in the WCER were suspected of extreme right-wing or racist ideological orientations, Ásatrúarfélagið members worried that Jormundur’s relationships with such Pagan groups might damage the reputation of the Society. Some also questioned the propriety of a business scheme of Jormundur to sell Icelandic horses in Eastern Europe. These controversies ultimately to Jormundur stepping down as Ásatrú High Priest.

The year 2000 was Iceland’s 1000th year anniversary of the vote to adopt Christianity at Þingvellir, the site of the ancient Icelandic parliament. “Christian Millennium” festivities were planned to take place in June at Þingvellir, organized by the national government in cooperation with the Evangelical Lutheran Church. However, the Ásatrú Society had its own plans for summer solstice rituals at Þingvellir at roughly the same time as the Millennium celebrations. This Christian versus Pagan conflict became a public controversy eventually resolved by granting both parties the right to perform their respective ceremonies. The inability of the church to expel the Pagans or to halt their un-Christian religious activities on the most hallowed ground in Iceland was a public relations coup for Ásatrúarfélagið, suggesting that the Society‘s claim to embody Icelandic national heritage was no less valid than that of the Church.

Despite continued membership growth, discontent with Jormundur continued to build, and in 2002, the executive board of the Society prevailed upon Jormundur to step down. Deputy Allsherjargoði Jónína K. Berg agreed to serve as interim High Priest for one year. In 2003, a new Allsherjargoði was elected: musician and composer Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson (1958-), who had been involved in Ásatrú from the age of sixteen.

The Ásatrú Society has begun building a hof (temple) in a wooded hill area in Reykjavík known as Öskjuhlíð, [Image at right] not far from Reykjavík’s famous, dome-shaped revolving restaurant, Perlan (the Pearl). City authorities donated the land for the temple to Ásatrúarfélagið in 2008, leaving the Society responsible for the temple construction itself. Under a dome-shaped roof, the temple will providing office space, guest lodgings, a library and research facilities, and a concert hall in addition to its main hall providing a comfortable, weather-sheltered space with a fire altar for ritual gatherings year-round.

The world financial crisis of 2008-2009 cut off construction, but work recommenced in 2015. New financial difficulties occasioned by the Covid-19 pandemic of 2019-2020 may again delay construction, but there is no talk of abandoning the project. When the temple is completed, it is likely to enhance the status of Ásatrúarfélagið as the leading Norse Pagan organization in the world.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

“Ásatrú” literally translates as “belief in (or trust or troth in) the Æsir,” but Ásatrú belief is considerably more variable than that formulation would suggest. Ásatrúarfélagið members do not regard the picture of the world given in Norse mythology as a literal description of the universe, but as a symbolic expression of the existence of a higher realm of being beyond our ordinary, everyday experience, and of the interrelatedness of that higher world or worlds with our own. The mythological picture of the World-Tree Yggdrasil connecting many worlds within its branches and roots is highly suggestive in this regard. The multiplicity of divine beings are an acknowledgement of complexity and diversity in nature, in society, and inside of each person.

Some Ásatrú followers may regard Norse gods like Odin, Thor, Freyr and Freyja as actual, super-powerful beings, as a Christian might conceive of Jesus or a Hindu might look on Krishna or Kali. For others, however, the gods’ value is mainly cultural, as a platform for Iceland’s pre-Christian, Pagan worldview. For yet others, the gods’ meaning is primarily symbolic, as timeless expressions of inner and outer realities, forces of nature as well as facets of the psyche and structures of society.

Freyr, for example, is a god of fertility in nature who also represents peace and kingship. [Image at right] His twin sister Freyja is associated with beauty and pleasure as well as war and death. Odin, the “All-Father” of many names and attributes, is a restless seeker of knowledge perpetually wandering across the worlds. He has two helper ravens named “mind” and “memory,” and gives to mankind the gift of poetry, that is to say, culture, while also ruling over the dead in Valhalla. Thor might seem no more than a god of strength and force, but his hammer mjölnir not only protects the earth from malevolent beings but is also used to sanctify marriages, bring rain, and raise the dead. These and other Norse deities provide the Ásatrú adherent with multiple meanings and purposes: seeking divine guidance according to the gods’ special areas of authority, connecting to Norse-Icelandic identity as bound up with the myths and poems of the Pagan gods, exploring one’s inner nature as reflected in the personalities and powers of the gods, and/or honoring the power and majesty of nature on daily display in the harsh and beautiful Icelandic landscape.

Ásatrú belief may seem maddeningly vague and variable, but this is a matter of both necessity and design. No ancient text gives any definite set of doctrines for the modern Norse Pagan to follow, only hints and fragments of beliefs and perspectives encoded in the mythological literature. There is no modern work that has gained acceptance as an authoritative interpretation. There is indeed little appetite among Icelandic Pagans for a central authority to impose an official doctrine. This preference for open-ended religious thought and rejection of any overbearing religious authority are common features of much modern-day Paganism, and may be well-suited to the “liquid modernity” of the early twenty-first century, when rapidity of communication and diversity of information and perspective come with a few clicks on the computer keyboard.

The myth of Ragnarök, a catastrophic battle of gods and demons, that is, forces of life and death, that lays waste to the entire earth is described in the Eddic poem Völuspá (the Speech of the Völva, that is, the seeress) and elsewhere. Odin, Thor and Freyr die in combat against demonic foes. This seems to presage the end of the world altogether, but after the earth is destroyed by fire and sinks into the ocean, it rises again, renewed. Ásatrúarfélagið members tend to see the myth of Ragnarök less as a literal prophecy of future events than as a symbolic warning of the danger of destruction that human beings may bring upon themselves and the earth through ignorance and malevolence. The death of Odin and the gods in Ragnarök is viewed as a poignant meditation on the inevitability of death, and the need to live with honor and integrity until that day arrives.

In terms of its social or political outlook, Ásatrúarfélagið may be characterized as somewhat left-wing and “green.” It has opposed racialized interpretations of Norse myth and heritage, embraced racial and gender equality, and strongly denounced neo-Nazism. The Society has lent its support to protests against opening the Icelandic natural environment to potentially harmful industrial development such as hydroelectric dams and aluminium mining.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

As an old-new religion designed to preserve beliefs and traditions of the past by adapting them to the present, Ásatrú ritual is not a slavish recreation of Pagan religious practices derived from Eddas, Sagas or other sources, but a fairly free-spirited reworking of such traditions that allows for new additions, alterations and interpretations as needed. The test for what to continue from the past and what to keep from new experiments is one that is wholly pragmatic and experiential: whatever religious activity seems to work well, to provide meaning, joy and inspiration to those involved, is kept and continued, and whatever is felt to be lifeless or meaningless or out of keeping with either ancient understandings or contemporary sensibilities is put aside. This is a dance that moves both forward and back, oscillating between the ancient and the now, between conservative and innovative impulses, often utilizing the artistic inclinations of Society members, as noted above.

Icelandic Ásatrú rituals are presided over either by the Allsherjargoði or other goðar (priests, the singular form being goði), who have regional jurisdictions, goðorð, organized according to Old Icelandic traditions, similar to Christian parishes. The presiding goði consecrates the gathering and guides the proceedings. Ásatrú rituals typically center on the recitation of Eddic poems or other selections from Old Norse-Icelandic literature, supplemented by speeches or poems created by the participants or officiants. This mixture of old and new texts maintains but also modernizes the traditional Icelandic dedication to poetic expression and verbal eloquence. Ritual actions likewise range from the recreation of religious behaviors noted in the Eddas and Sagas to newly invented behaviors or gestures. The continual turning back to the older texts demonstrates how deeply rooted in Icelandic literary culture Ásatrúarfélagið is.

A text often used in many rituals, including weddings and funerals, is an invocation from the Eddic poem Sigrdrífumál:

Hail to the Day, hail to the sons of Day

Hail to the Night and her Daughters

Look upon us with kindly eyes

And grant to us all victory.Hail to the Gods, hail to the Goddesses

Hail to the bountiful Earth

Grant us speech and wisdom and healing hands

As long as we shall live.

(Sigrdrífumál v. 3-4, Poetic Edda, Jormundur Ingi Hansen translation,

revised by Michael Strmiska.)

The primary public or collective rituals, in which the entire Ásatrúarfélagið membership is invited, though not compelled, to participate, are the seasonal blóts, [Image at right] sacred feasts observed at intervals roughly corresponding to the summer and winter solstices and the spring and autumn equinoxes. In olden times, the blót included animal sacrifice; the contemporary version usually centers on a drinking and toasting ceremony. The ceremony is known as the sumbel; participants form a circle around a sacred fire and take turns speaking and drinking, taking mead or other liquor or a non-alcoholic beverage from a drinking horn or other vessel passed around the circle, with the bearer of the horn the one who speaks.

The horn is typically passed around the circle three times, giving each participant the opportunity to speak and to share in the common liquid offering. On the first passing of the horn, the participants offer tribute to the higher levels of spiritual existence: to the Norse gods, to other supernatural beings, or whatever else is felt most sacred and significant. This often involves reading or reciting passages from Eddic poems or other ancient texts, though more spontaneous or personal utterances, such as self-composed poems or proclamations, are also welcome. The second time around, the dead and the ancestors are honored, which could range from commemorating family members to offering verbal tribute to respected figures in the larger society such as artists, poets, or politicians. The third passing of the horn is for the community of the living and the world of here and now. Each person is free to speak of whoever or whatever in their current life they wish to honor, congratulate, thank or express sympathy or concern for, even political or social matters of the day. The relationship of sumbel to blót is that the blot is the general occasion of gathering together for religious celebration and contemplation, and the sumbel is the focal point, the apex of the blót.

This basic pattern can be adapted according to the needs or wishes of the individuals involved, but the trajectory from the highest, most sacred realm in the first round of toasting to the more mundane and immediate world of today in the final round is a well-respected pattern. Mead, a traditional drink of the ancient Germanic and Scandinavian peoples, is the beverage of choice, brewed from honey and herbs. The drinking-horn from which the ritual beverage is drunk is fashioned, in accordance with ancient tradition, from the horn of a stag or some similarly large and impressive animal. Food may also be consumed, with a preference for traditional foods such as hearty dark bread or smoked lamb meat. Participants may wear medieval-styled clothing such as cloaks or tunics embroidered with traditional designs, such as runes, along with metal rings, pendants or other jewelry inspired by Viking designs. Tattoos utilizing traditional designs have become popular in recent times. The gathering around a fire, the invoking of ancient gods, the reciting from ancient texts, the eating and drinking of traditional food and drink, and the adornment of the body with items of vintage medieval style combine to create a sense of connection with the Icelandic past and Norse Pagan spirituality.

Private or personal rituals performed for individuals, families and children range from the “name-giving” blessing of infants to a coming-of-age ritual like a Pagan Bar Mitzvah to weddings to funerals. Ásatrúarfélagið has its own cemetery on the outskirts of Reykjavík where Sveinbjörn and other members have been laid to rest. These private rituals vary widely to suit the individual tastes and needs of the participants. They typically involve recitation from Eddic or other sacred Icelandic texts, the invocation of Pagan gods, and varying display or use of traditional items. These include the brandishing of a Thor’s hammer amulet to bless a marriage or a baby, or a couple taking wedding vows jointly clasping a heavy copper ring. These smaller-scale personal ceremonies can be just as successful as their larger-scale public counterparts in evoking the archaic but accessible atmosphere so appealing in modern Paganism.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The founders of Ásatrúarfélagið viewed Paganism as a foundational element of Icelandic culture. All of the Society’s High Priests have been people of artistic temperament and interests, from the poet Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson, to the erudite and eloquent Jormundur Hansen, to the artist and photographer Jónína K. Berg, to the composer and keyboardist Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson. The Ásatrú Society has welcomed collaborations with artists, musicians, and others to give compelling artistic expression to Ásatrú myths, beliefs and traditions. Notable examples include a theatrical dramatization of the Eddic poem Skírnismál directed by folklore professor Terry Gunnell in the early 1990s and the 2002 debut of a Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson composition accompanying the mythological poem Hrafnagaldur Óðins (“Odin’s Raven-Magic”), with a symphonic orchestra led by Hilmarsson, who played a massive “Viking marimba” made of Icelandic stone, accompanied by the superstar rock band Sigur Rós. Such artistic engagements with Pagan myths and traditions have no doubt added to the appeal of Ásatrú in Iceland.

Ásatrúarfélagið’s literary-artistic-cultural focus distinguishes Icelandic Ásatrú from versions of modern Norse Paganism that have developed in other parts of the world. In the U.S., for example, Ásatrú has often been presented as a “warrior religion” harking back to the days of the Vikings, with particular appeal to members and admirers of the American military. This difference in interest and emphasis has lent some American forms of Norse Paganism a hyper-masculine, militaristic character that is generally lacking in Icelandic Ásatrú, except as fodder for jokes.

Ásatrúarfélagið [Image at right] has several overlapping governing structures, ranging from the Logrétta (Adminstrative Council, more literally the “Law-Court”), to the Framkvaemdastjórn (Executive Board), to the Allsherjarðing (the General Assembly, more literally the “thing” (parliament) “of all people.”) The overall administrative structure of Ásatrúarfélagið has proven stable and workable.

The Allsherjargoði is the overall leader of Ásatrú. This position has gradually evolved into a lifetime appointment, with recall or impeachment possible through majority vote at the General Assembly. The Allsherjargoði is the main spokesman for the association, responsible for public relations and representing the group on ceremonial occasions. His most important ceremonial role is in consecrating the National Parliament each year, with an equivalent Christian blessing administered by an official of the state church. The Allsherjargoði likewise consecrates all Ásatrú meetings that he attends and takes the lead role in all Ásatrú rituals and activities. The Allsherjargoði is legally empowered to perform weddings, funerals, and other such life-cycle rites, as well as to sanctify contracts of all sorts, for which he is entitled to charge small fees. As noted above, there are also local goðar (priests and priestesses) responsible for particular Pagan parishes, who are empowered to perform the same rites and collect the same fees. Neither the Allsherjargoði nor the goðar receive a salary.

The Executive Board handles the Ásatrú Society’s everyday operations and finances. The Board consists of the Lögmaður (the “Lawspeaker,” more literally the “law-man” or “lawyer”), a Secretary, a Treasurer and one Member-at-Large without specific duties. The Lawspeaker’s role is to preserve official documents and promote fealty to the laws of the organization, appoint board members to specific positions, and preside over board meetings. The Executive Board meets at least four times per year, with responsibility for organizing blót-feasts and the General Assembly.

The Administrative Council is composed of the Allsherjargoði, the other goðar, and the Executive Board, and meets thrice annually in addition to the annual General Assembly meeting on the last Saturday in October. Council meetings are open to the general membership of the Ásatrúarfélagið but only council officials are empowered to vote. Administrative Council meetings review and may overrule Executive Board decisions, address disputes between members, and allow for open discussion of the overall state of the Society.

Administrative Council decisions are subject to further discussion and vote at the Allsherjarðing (the General Assembly, more literally the “thing of all people”). This is in many ways the most powerful governing structure, as well as the most democratic and inclusive one, open to all Society members in good standing twelve years and older. Changes in the association’s laws and procedures can only be made, and major initiatives and expenditures undertaken, with a two-third majority approval of the Allsherjarðing. The General Assembly also elects the members of the Executive Board.

ISSUES AND CHALLENGES

From the vantagepoint of 2020, Ásatrúarfélagið can boast of five decades of successful operation as a small but growing religion in Iceland. It has found acceptance in Icelandic society, remained free of any major scandals, seen its membership triple in the last ten years from 1.402 in 2010 to 4,473 in 2019, and embarked on the construction of an impressive house of worship. Continued membership growth may place strains on the organization of the Society or lead to schisms between different groups with differing views of how Norse Paganism should be interpreted or practiced, but there is no sign of any significant discord at the current time.

The single greatest challenge Ásatrúarfélagið faces is in maintaining a form of Norse Pagan religion that is both grounded in ancient Icelandic texts and traditions and welcoming toward the racial and ethnic diversity of modern times, in opposition to more racialized and white supremacist forms of Norse Paganism that have developed in other countries.

IMAGES

Image #1: Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson.

Image #2: Jormndur Ingi Hansen.

Image #3: Rendering of the planned Asatru temple in Reykjavík.

Image #4: Freyr, a god of fertility in nature.

Image #5: Asatru members participating in a seasonal blót.

Image #6: Ásatrúarfélagið logo.

REFERENCES

Adalsteinnson, Jón Hnefill. 1978. Under the Cloak: The Acceptance of Christianity in Iceland. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Uppsala: Almqvist and Wiksell International.

Adalsteinnson, Jón Hnefill. 1990. “Old Norse Religion in the Sagas of the Icelanders.” Gripla 7:303-22.

Byock, Jesse (Translated). 2005. The Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson. London: Penguin Books.

Christiansen, Eric. 2002. The Norsemen in the Viking Age. Oxford and Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Davidson, H.R. Ellis. 1964. Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. London: Penguin Books.

Faulkes, Anthony (Translated). 1995. Edda–Snorri Sturluson. London: Everyman Books.

Faulkes, Anthony, and Richard Perkins, eds. 1993. Viking Revaluations: Viking Society Centenary Symposium, May 14-15, 1992. London: Viking Society.

Finnestad, Ragnhild Bjerre. 1990. “The Study of the Christianization of the Nordic Countries. Some Reflections.” Pp. 256-72 in Old Norse and Finnish Religions and Cultic Place Names, Based on Papers Read at the Symposium on Encounters Between Religions in Old Nordic Times and on Cultic Place-Names Held at Åbo, Finland, on the 19th-21st of August 1987, edited by Tore Ahlbäck. Åbo: Donner Institute.

Gardell, Mattias. 2003. Gods of the Blood: The Pagan Revival and White Separatism. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. 1992. The Occult Roots of Nazism: Secret Aryan Cults and Their Influence on Nazi Ideology. New York: New York University Press.

Gunnell, Terry. 2015. “The Background and Nature of the Annual and Occasional Rituals of the Ásatrúarfélag in Iceland.” Pp. 28-40 in The Ritual Year 10, Magic in Rituals and Rituals in Magic. The Yearbook of the SIEF (Société Internationale d’Ethnologie et de Folklore) Working Group on the Ritual Year, edited by Tatiana Minniyakhmetova and Kamila Velkoborská. Tartu and Innsbruck: University of Tartu Press.

Hagstofa Íslands [Iceland Statistical Office]. 2019. Mannfjöldi eftir sóknum, prestaköllum og prófastsdæmum 1. desember 2019 [population by parishes, priestly vocations and dioceses 1 December 2019]. Accessed from http://px.hagstofa.is/pxis/pxweb/is/Samfelag/Samfelag__menning__5_trufelog/MAN10293.px/?rxid=47bdb80e-26cd-421e-a91e-0b45c7929e1c on 5 July 2020.

Halink. S. 2017. Asgard Revisited: Old Norse mythology and national culture in Iceland, 1820-1918. PhD Dissertation, University of Groningen.

Harvey, Graham. 2000. “Heathenism: A North European Pagan Tradition.” Pp. 49-64 in Pagan Pathways: A Guide to the Ancient Earth Traditions, edited by Graham Harvey and Charlotte Hardman. Second Edition. London: Thorsons.

Helgason, Magnús Sveinn. 2015. “Heathens against hate: Exclusive interview with the high priest of the Icelandic Pagan Association.” Iceland Magazine, July 25. Accessed from https://icelandmag.is/article/heathens-against-hate-exclusive-interview-high-priest-icelandic-pagan-association on 27 December 2017.

Hollander, Lee (Translated). 1962. Revised Edition. The Poetic Edda: Translated with an Introduction and Explanatory Notes. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

“Members of pagan Ásatrú Association conduct ceremony to thank Mother Nature for timber used to construct temple.” 2016. Iceland Magazine, June 6. Accessed from https://icelandmag.is/article/members-pagan-asatru-association-conduct-ceremony-thank-mother-nature-timber-used-construct on December 27, 2017.

“Iceland to build first temple to Norse gods since Viking age.” 2015. The Guardian, February 2. Accessed 1 March 2015 from http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/feb/02/iceland-temple-norse-gods-1000-years on 1 August 2020.

Kaplan, Jeffrey. 1997. Radical Religion in America. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Karlsson, Gunnar. 2000. The History of Iceland. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Karlsson, Gunnar. 1995. “The Emergence of Nationalism in Iceland.” Pp. 33-62 in Ethnicity and Nation Building in the Nordic World, edited by Sven Tagil. London: Hurst & Company.

Kristjánsson, Jónas. 1988. Eddas and Sagas: Iceland’s Medieval Literature. Translated by Peter Foote. Reykjavík: Hið Íslenska Bókmenntafelag.

Larrington, Carolyne (Translated). 2014. The Poetic Edda (2nd ed.), Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lindow, John. 2002. Norse Mythology. A Guide to Gods, Heroes, Rituals and Beliefs. Cambridge: Oxford University Press.

Lönnroth, Lars. 1991. “Sponsors, Writers, and Readers of Early Norse Literature.” Pp. 3-10 in Social Approaches to Viking Studies, edited by Ross Sampson. Glasgow: Cruithne Press.

Portraits in Faith Series. 2014. “Interview with Jóhanna Harðardóttir,” June 9. Accessed from https://portraitsinfaith.org/johanna-hardardottir/ on 27 December 2017.

Seigfried, Karl. 2014. “Sigurblót: What is Victory?” Norse Mythology blog, April 24. Accessed from http://www.norsemyth.org/2014/04/sigurblot-what-is-victory.html on March 1, 2015.

Seigfried, Karl. 2011. “Interview with Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson of the Ásatrúarfélagið.” Norse Mythology blog, June 23. Accessed from http://www.norsemyth.org/2011/06/interview-with-hilmar-orn-hilmarsson-of.html on 1 March 2015.

Sigurdsson, Gísli. 2005. “Orality and Literacy in the Sagas of Icelanders.” Pp. 285-301 in A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture, edited by Rory McTurk. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Strmiska, Michael. 2018. “Pagan Politics in the 21st Century: ‘Peace and Love’ or ‘Blood and Soil’?” The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies 20:25-64.

Strmiska, Michael. 2007. “Putting the Blood Back into Blót: The Revival of Animal Sacrifice in Modern Nordic Paganism.” The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies 9:154-89.

Strmiska, Michael. 2003. “The Evils of Christianization: A Pagan Perspective on European History.” Pp. 59-72 in Cultural Expressions of Evil and Wickedness: Wrath, Sex, Crime, edited by Terry Waddell. New York and Amsterdam: Rodopi Press.

Strmiska, Michael. 2000. “Ásatrú in Iceland: The Rebirth of Nordic Paganism?” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 4:106-32.

Strmiska, Michael. 1995. “Odin, Loki, Thor: Grim Gods and Gallows Humor in Scandinavian Mythology.” Explorations: Journal for Adventurous Thought 14:79-91.

Strmiska, Michael with Baldur A. Sigurvinsson. 2005. “Ásatrú: Nordic Paganism in Iceland and America.” Pp. 127-69 in Modern Paganism in World Cultures, edited by Michael Strmiskak. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Turville-Petre, Edward Oswald Gabriel. 1964. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Publication Date:

5 August 2020.