BAHA’I FAITH TIMELINE

1844 (May 22-23): The Bab’s declaration of mission to Mull a Husayn was made.

1850 (July 8/9): The Bab was executed.

1852 (August 15): The Babi remnant split into factions, one of which made an attempt on the life of Nasiri’d Din Shah.

1856-1863: Baha’u’llah gradually revivified the Babi community.

1863: Baha’u’llah was moved to Istanbul and then Edirne.

1866: Baha’u’llah made a formal announcement to be the promised one foretold by the Bab and referred for the first time to his followers as Baha’is. Most of the Babis became his followers.

1892 (May 29): Baha’u’llah died. He designated his eldest son ‘Abdu’l-Bah a as head of the Faith.

1894: Ibrahim Kheiralla began Baha’i teaching activity in Chicago. The first Americans converted to Baha’i.

1911-1913: ‘Abdu’l-Baha undertook two tours of Europe and one of North America.

1921 (November 28): `Abdu’l-Bah a died.

1922 (January): Shoghi Effendi was publicly named as Guardian and began the process of consolidating the system of Baha’i administration.

1934-1941: A campaign of official persecution against the Baha’is in Iran took place.

1937-1944: The first American Seven Year Plan marked the beginning of systematic Baha’i teaching campaigns. The Baha’i Faith was banned in Nazi Germany.

1938: There were mass arrests and exile of Baha’is in Soviet Asia.

1953-1963: The Ten Year ‘Global Crusade’ marked the beginning of a series of international teaching plans.

1957 (November 4): Shoghi Effendi died in London. The Hands of the Cause assumed leadership of the Baha’i world.

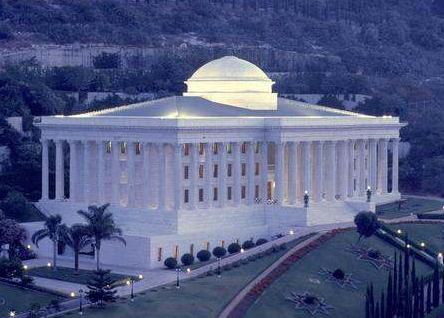

1963 (April 21-22): The Universal House of Justice was established in Haifa.

1963 (April 28-May 2): The first Baha’i world congress was held in London.

1970: All Baha’i institutions and activities were banned in Iraq. The Baha’i International Community gained consultative status with the United Nations’ Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC).

1972: The Universal House of Justice adopted its Constitution.

1979: The Islamic revolution in Iran took place. Major persecution of Baha’is began. The House of the B a b was destroyed.

1983: The Baha’i Office of Social and Economic Development was established. The Baha’i Faith was officially banned in Iran.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The Baha’i Faith developed out of the earlier Babi movement (Amanat 1989; MacEoin 2009; Smith 1987:5-56; Smith 2007:3-15). This movement centered on a young Iranian merchant, Sayyid ‘Al i-Muhammad Shirazi (1819-1850). He was initially widely regarded as claiming to be the Bab (Gate) to the messianic Hidden Imam of Shi’i Islam (May 1844), his followers thus coming to be called Babis. Later the Bab made explicit claim to be the Mahdi, the return of the Imam himself. However, even the claim to be the Bab was revolutionary in a Shi’i context, as in the presence of the Imam all other authorities (religious and secular) could only retain legitimacy by obedience to him.

From the beginning, Babi missionaries were opposed by high-ranking Shi’i clerics, and several violent incidents occurred. Meanwhile, the Bab sought to gain the support of the Persian king, Muhammad Shah, but was instead imprisoned by the powerful chief minister in a remote fortresses. In the confusion following the death of the Shah in September, 1848, an armed conflict broke out in one of the northern provinces between a large band of Babis and their religious opponents. The Babis fought what they saw as a defensive and sacrificial struggle against the forces of unbelief in an apocalyptic battle heralding the day of judgement. State intervention led to the extirpation of the Babi band, but two further conflicts between the Babis and their enemies convinced the vizier of the new shah to have the Bab executed in July, 1850 as a means of destroying the movement’s primary inspiration.

The surviving Babis continued their activities in secret and broke into several factions following various secondary leaders. One of these factions decided to assassinate the new shah as an act of revenge in August 1852. The attempt was badly bungled, and many Babis were rounded up and imprisoned or killed, including several prominent leaders who were not involved in the assassination plot. The Babi Movement seemed to have been destroyed.

That the movement survived was primarily the achievement of Mirza Husayn-‘Ali Nuri (1817-1892), eventually generally known by his title “Bahá’u’lláh” (The “Glory of God”) (Momen 2007 ; Smith 1987:57-66; Smith 2007:16-23). Although uninvolved in the plot against the Shah, he was thrown into prison and later exiled to what was then Ottoman Iraq. From there he began to correspond extensively with the scattered Babis in Iran. His writings conveyed his own sense of the divine presence and gave reassurance to the demoralized Babis. Less esoteric than the writings of the Bab, they often emphasized the importance of practical morality as well as the mystic path. Increasingly, the movement centered on him. This distressed his young half-brother, Mīrzā Yaḥyā

(1831/2-1912), “Subh-i Azal” (the “Morn of Eternity”), who explicitly claimed leadership of the Babis but led a secret existence separate from them.

The revival of the Babis attracted the attention of the Ottoman authorities, who moved Baha’u’llah and his immediate followers away from close proximity to the Iranian border to the city of Edirne in the Balkans (1863). Here, Baha’u’llah made explicit claim in 1866 to be the promised redeemer prophesied by the Bab. His followers soon came to include most of the remaining Babis in Iran, coming to call themselves Baha’is, while a small minority followed Subh-i Azal and became known as Azali Babis.

Further exile in 1868 saw Baha’u’llah transferred to the prison-city of Akka ( Acre) in what was then Ottoman Syria. He remained in or near Akka for the rest of his life, during which period the Baha’i Faith took shape as an organized religion. Baha’u’llah continued to write extensively, revealing his own code of divine law, outlining his vision for a united and just world, and sending a series of letters to some of the major world leaders proclaiming his mission. Meanwhile, Baha’i migrants and teachers established Baha’i groups in various parts of the Ottoman Empire, as well as in Egypt, Russian Turkestan, and British India and Burma. Effective organization ensured that the now multinational Baha’i groups remained in close contact with Baha’u’llah and that copies of his writings were widely distributed. There was also some printing of Baha’i literature in India (Cole 1998; Momen 2007; Smith 1987:66-99; Smith 2007:23-41).

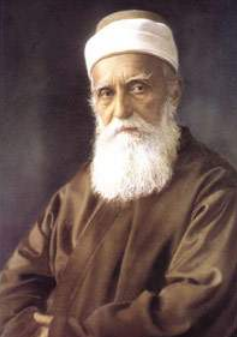

Baha’u’llah appointed his eldest son, “Abbas” (1844-192), ‘Abdu’l-Baha (the “Servant of Baha”) to lead the Baha’is after his

death (Balyuzi; Smith 2007:43-54). ‘Abdu’l-Bah a was then almost fifty, well known to the Baha’is, and greatly respected as his father’s chief assistant. As a result, the appointment was readily accepted, despite opposition from his own half-brother, Muhammad-‘Ali (1853/4-1937), and a small band of supporters.

death (Balyuzi; Smith 2007:43-54). ‘Abdu’l-Bah a was then almost fifty, well known to the Baha’is, and greatly respected as his father’s chief assistant. As a result, the appointment was readily accepted, despite opposition from his own half-brother, Muhammad-‘Ali (1853/4-1937), and a small band of supporters.

The almost thirty years of ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s leadership was a crucial period of change for the Baha’i Faith, most dramatically with the growth of small Baha’i communities in North America and Europe. Although only a few thousand in number, the new Western Baha’is vividly demonstrated the international nature of the Faith and became an extremely active element in Baha’i publishing and teaching activities (Smith 1987:100-14; Smith 2004). ‘Abdu’l-Baha himself was able to visit the Western Baha’is in two lengthy tours in 1911-1913. Meanwhile, in Iran, despite worsening persecution, the Baha’is were able to impress an increasing number of “progressive” Iranians with the relevance of their ideas of social reform, as well as successfully establishing a number of Baha’i schools and furthering the emancipation of women within the community.

With no living sons of his own, ‘Abdu’l-Bah a was in turn succeeded by his eldest grandson, Shoghi Effendi Rabbani (1897-1957), who he appointed as the first in a projected line of “Guardians” of the Faith. Shoghi Effendi’s Guardianship lasted from January, 1922 until his death (Smith 1987:115-28; Smith 2007: 55-69). During his Guardianship, he consolidated a system of elected local and national Baha’i councils (“spiritual assemblies”) to administer the affairs of Baha’ism ; produced a number of significant English-language translations of the writings of Baha’u’llah and ‘Abdu’l-Baha; defined matters of Baha’i doctrine; and oversaw the extension of the buildings and gardens of the “Baha’i World Centre” in the Haifa-Akka area. He also directed a series of increasingly ambitious expansion plans to spread the Faith throughout the world.

Shoghi Effendi died suddenly in 1957. He had no children, and a body of twenty-seven senior Baha’is who he had recently

appointed as “Hands of the Cause” assumed temporary leadership of the Faith pending the election of the Universal House of Justice (an international council referred to in the Baha’i scriptures) in 1963. With successive changes in its elected membership, the Universal House of Justice has remained in charge of the Baha’i community since 1963 (Smith 1987:128-35; Smith 2007:68-77).

appointed as “Hands of the Cause” assumed temporary leadership of the Faith pending the election of the Universal House of Justice (an international council referred to in the Baha’i scriptures) in 1963. With successive changes in its elected membership, the Universal House of Justice has remained in charge of the Baha’i community since 1963 (Smith 1987:128-35; Smith 2007:68-77).

The most obvious characteristic of the modern Baha’i Faith is perhaps its internationalization, particularly since the 1950s. Baha’i communities have been established in virtually every country in the world; converts have come from a diverse array of cultural and religious backgrounds; the global following has been estimated to be around five million. Although the Iranian Baha’is, who themselves have been severely persecuted since the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979, remain an important part of the global Baha’i community, the Baha’is can now rightfully claim to be a worldwide religion. There are particularly large memberships in India and parts of Africa and Latin America. Linked to this development is an increasing range of Baha’i literature addressing a great variety of religious and secular issues (Smith 1987:146-54, 157-95; 2007:78-96).

A second characteristic is the maintenance of the religion’s unity despite challenges to each of the leaders since Baha’u’llah from small and relatively transient, dissident groups. This is seen by Baha’is as evidence of the importance of their doctrine of a Covenant of succession. A third characteristic, evident in Iran since the late nineteenth century and elsewhere since the 1960s, has been the increasing importance of educational and other socio-economic development projects within the Baha’i faith.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Authoritative Baha’i teachings are derived from the original writings of the successive leaders of the Baha’i religion, and in the case of ‘Abdu’l-Baha , approved transcripts of his public talks. There is no Baha’i sacred or liturgical language. Arabic, Persian and English have a special status as the languages of the original writings of the Baha’i leaders, but access to and understanding of the texts is what is regarded as of primary importance. The result is that extensive translation programs of Baha’i scriptures and other literature have long been an important part of Baha’i endeavour (Smith 2007: 99-105).

of ‘Abdu’l-Baha , approved transcripts of his public talks. There is no Baha’i sacred or liturgical language. Arabic, Persian and English have a special status as the languages of the original writings of the Baha’i leaders, but access to and understanding of the texts is what is regarded as of primary importance. The result is that extensive translation programs of Baha’i scriptures and other literature have long been an important part of Baha’i endeavour (Smith 2007: 99-105).

The Baha’i Faith is strictly monotheistic. However, because God in essence is unknowable, all human conceptions of God are mere imaginations, which some individuals mistake for reality. Therefore, knowledge of God is primarily to be achieved by way of his messengers: the “Manifestations of God.”

According to the Baha’i view, these Manifestations of God represent the divine presence to humankind. They include Adam, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, Zoroaster, Krishna and the Buddha, and for the present age, the Bab, and Baha’u’llah. Each has his own specific mission, but they all also share an “essential unity” that transcends the diversity of the world’s various religions. Each is authoritative and infallible. For Baha’is, the development of the Baha’i Faith forms part of a single overarching history of religion on this planet, a process of ” progressive revelation” that encompasses all of the major world religions. Each of the Manifestations of God has brought divine teachings appropriate to the needs of the people of their own particular time and place (Smith 2007:106-11, 124-32).

Of Baha’i descriptions of the nature of reality, the most striking perhaps is the view that evil has no objective reality other than in the evil deeds of human beings. There is no devil or satan, nor evil spirits nor demonic possession. Rather God’s creation is good. It is human rebellion against God that generates evil.

For Baha’is, human beings possess both a physical body and a non-material, rational soul. The soul is the essential inner reality of each human being. It comes into existence at the time of conception, and enters a new existence after death. All human beings can realize their inherent spiritual potential if they turn to God and seek to acquire spiritual qualities.

Individuals achieve different levels of spiritual development as a consequence of their choices. These levels are symbolically described in terms of “heaven” and “hell,” which in reality are states of soul rather than physical places. Thus, those who are close to God are in “heaven,” while those who are distant from him are in “hell,” a distinction that applies in both this life and the afterlife (Smith 2007:117-23).

For Baha’is, Baha’u’llah came to unite all the peoples of the world; bring together the followers of the world’s religions; and establish the future millennial age, which has been prophesied in all religions (Smith 2007:133-47). This ideal ultimately requires a spiritual transformation of humankind, but the Baha’is point to various pragmatical and proximate means to work towards this vision. These include:

1. The achievement of world peace in a united world, which includes such mechanisms as armament reductions, much of the work of the United Nations, and the promotion of tolerance and freedom from all religious and racial prejudices.

2. The establishment of social order and justice, which includes the promotion of good governance, the rule of law, and the protection of the poor and downtrodden at national and international levels.

3. The advancement of women. For Baha’is, men and women are equal in the sight of God, and the human race as a whole can only progress if both sexes have full opportunity to realize their potentials. The oppression of woman, wherever it occurs, prevents that progress.

4. Education. Both religious-moral and “secular” education are required for the individual and for society as a whole to advance. Universal access to education is seen as a fundamental right, with the education of girls, as potential mothers and hence their own children’s first educators, being of particular importance.

5. The role of religion. Solutions to the world’s problems depend on a combination of “spiritual” and “material” principles. Materialism and secularism are destructive social forces in the modern world, but religion itself should be shorn of fanaticism, bigotry and superstition.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

For Baha’is, spirituality and morality are linked together in the concept of the spiritual “path,” whereby the individual believer strives to develop spiritual-moral qualities (Smith 2007:151-56). Rather than provide a rigid code of behavior, the Baha’i teachings mostly state general principles, with the premise that individual Baha’is should use their own consciences and understanding to apply these principles in the particular contexts of their own lives.

Central to this path is that Baha’is should turn to God and find the divine light present in all human beings within themselves. Prayer and contemplation of the Baha’i scriptures are means to this end. Baha’is should also review their own actions, bringing themselves to account each day.

Relationships with other people are a crucial part of the spiritual path. Baha’is should strive to be loving to all human beings of whatever religion, race, or community; they should exercise such qualities as loyalty, compassion and selflessness, truthfulness and trustworthiness. They should completely avoid envy, malice, backbiting and all forms of dishonesty. Baha’is should be tolerant of others, particularly in matters of religion. Fanaticism and “unreasoning religious zeal” are condemned.

Being a Baha’i also involves following Baha’i law (Smith 2007:158-74). The main elements are:

1. Personal obligations towards God. These obligations include daily prayer and reading of Baha’i scripture; an annual nineteen day fast from sunrise to sunset for those who are fit and well; and payment of Huququ’llah (the “Right of God”), a form of voluntary tithe on increases in net assets for those who are sufficiently wealthy.

2. The sanctity of marriage and family life. A Baha’i marriage requires the consent of both the couple and their parents, with this latter permission being required so as to strengthen ties between family members. Baha’i marriage is monogamous. Child marriage is not allowed. Divorce is permitted, but strongly discouraged. Parents must ensure the education of their children. All forms of injustice and violence within the family are condemned.

3. Aspects of individual life. The sexual impulse can only be legitimately expressed in marriage. All forms of pre- and extra-marital sexual relationships are thus forbidden, as is the practice of homosexuality. Alcohol, opiates and other psychoactive drugs are also forbidden, unless prescribed by a physician. Tobacco smoking is discouraged but not forbidden. There is no required use of Baha’i symbols of identity.

4. Relationship to civil society and the state. Baha’is are required to follow the law of the countries in which they reside unless these laws require them to deny their faith or violate fundamental Baha’i principles. They must strictly avoid sedition and avoid any party-political involvement.

5. Sanctions. In general, observance of most Baha’i laws is regarded as a matter of individual conscience, and only extreme and public breaches of the law are normally sanctioned. Normally sanctions take the form of depriving the individual of the right to participate in Baha’i elections and contribute to the Baha’i funds. Only national spiritual assemblies can deprive an individual of his or her voting rights, and normally this is only a last resort.

One focus for Baha’i identity are the variety of activities organized by local Baha’i communities, including regular “Nineteen Day  Feasts” during which members of the local Baha’i community come together to pray and consult on matters of concern. Another is the celebration of the Baha’i holy days commemorating events in the lives of the Bab, Baha’u’llah and `Abdu’l-Baha. Baha’is have their own calendar, consisting of nineteen months each of nineteen days (361 days), with four or five “intercalary days” to make a solar year. The new year is the ancient Iranian new year of Naw-Ruz, normally March 21 at the spring equinox. The first year of the calendar is 1844, the year of the Bab’s declaration; therefore, the Baha’i year 170, for example, began at Naw-Ruz 2013.

Feasts” during which members of the local Baha’i community come together to pray and consult on matters of concern. Another is the celebration of the Baha’i holy days commemorating events in the lives of the Bab, Baha’u’llah and `Abdu’l-Baha. Baha’is have their own calendar, consisting of nineteen months each of nineteen days (361 days), with four or five “intercalary days” to make a solar year. The new year is the ancient Iranian new year of Naw-Ruz, normally March 21 at the spring equinox. The first year of the calendar is 1844, the year of the Bab’s declaration; therefore, the Baha’i year 170, for example, began at Naw-Ruz 2013.

Various sites associated with the Bab, Baha’u’llah and ‘Abdu’l-Baha are considered holy by Baha’is, the most important being the various holy places at the Baha’i World Center in the Haifa-Akka area. Many Baha’is endeavour to make a pilgrimage to these sites at least once in their lifetimes. Some of these places are also open to the general public, the “Baha’i Gardens” in Haifa having become a major tourist destination. The Shrine of Baha’u’llah at Bahj’i is the Baha’i “qiblah” (the “point of adoration”) to which Baha’is throughout the world turn when the say their daily obligatory prayers. Important Baha’i sites in Iran are either inaccessible or have been destroyed by the authorities since the establishment of the Islamic Republic (Smith 2007:157-58, 187-97).

All Baha’is are encouraged to ” promote the Faith” and gain new adherents through the teaching and proclamation of the Baha’i teachings, but this should be non-disputatious and avoid heavy-handed proselytizing. Some Baha’is spend considerable periods of time as “travel teachers,” travelling from one place to another to teach their faith, while others “pioneer” to commence or support Baha’i activities in new locations. There are no full-time professional Baha’i promoters of the Faith.

There is a lot of Baha’i activity in support of its vision of social reconstruction. This includes the promotion of religious tolerance; the advancement of women; the development of education (there are a number of Baha’i schools and at least one college worldwide open to people of all religions); literacy training; and socio-economic development, with particular emphasis on sparking change at the grassroots level (Smith 2007:198-210).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The various local and national Baha’i communities are structured around the Baha’i Administrative Order under the overall  guidance and direction of the Universal House of Justice (Smith 2007:175-86). There are two branches: a system of annually elected nine-member local and national spiritual assemblies, which organize and administer the collective lives of the Baha’is in their respective communities, and the various “institutions of the learned” (an International Teaching Centre in Haifa, and appointed individuals at continental and local levels), who are concerned with enthusing and advising the Baha’is.

guidance and direction of the Universal House of Justice (Smith 2007:175-86). There are two branches: a system of annually elected nine-member local and national spiritual assemblies, which organize and administer the collective lives of the Baha’is in their respective communities, and the various “institutions of the learned” (an International Teaching Centre in Haifa, and appointed individuals at continental and local levels), who are concerned with enthusing and advising the Baha’is.

The Baha’i writings frequently emphasize the need for the Baha’i administration to embody a specific “spirit of humility” and free consultation. This ideally involves all community members and is regarded as an essential means whereby individual voices can be heard and a variety of views examined dispassionately. There are also appeals procedures for those Baha’is who wish to question the decisions of their local and national spiritual assemblies.

Funding for Baha’i activities comes from both the Huququ’llah system (above) and the voluntary contribution of the Baha’is to various funds at local, national, continental and international levels. All contributions are a strictly personal matter, determined purely by the dictates of conscience. Only Baha’is are allowed to contribute to funds supporting the direct work of the Faith.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

The Baha’i Faith is now a worldwide movement and the challenges which face Baha’i communities in one part of the world may be quite different from those in another. For the Baha’is in the Middle East the key issue is religious freedom. In Iran, the Baha’is have faced an ongoing campaign of persecution ever since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Despite being the largest religious minority in the country, they have faced waves of arrests of their leaders and particularly active members (around 200 of whom have been murdered or executed); the banning of all their activities; and the attempt to totally exclude them from all aspects of civic life (including education and the burial of their dead). Considerable difficulties have also been encountered by the Egyptian Baha’is, who have also been denied many civil rights.

By contrast, while the Baha’is in the West have often been able to gain considerable public attention and sympathy, their numbers have generally remained small, leading to anxieties in some circles about the failure to achieve a greater impact. A small number of Western Baha’is have also expressed discontent over Baha’i practices that they deem illiberal, notably the restriction of membership of the Universal House of Justice to men and the prohibition on homosexual activity, including homosexual marriage. Intellectual tensions have also surfaced about “academic” interpretations of the Faith.

It is very difficult to make any generalizations about the very diverse Baha’i communities of the Third World. In a number there are certainly practical challenges in consolidating a national Baha’i community with limited resources and in dealing with harsh social realities, including the displacement of refugees, poverty and crime.

REFERENCES

Amanat, Abbas. 1989. Resurrection and Renewal: The Making of the Babi Movement in Iran, 1844-1850. Ithica, NY: Cornell University Press.

Balyuzi, H. M. 1971.`Abdu’l-Baha: The Centre of the Covenant of Baha’u’llah. London: George Ronald.

Cole, Juan R. I. 1998. Modernity and the Millennium: The Genesis of the Baha’i Faith in the Nineteenth-Century Middle East. New York: Columbia University Press.

MacEoin, Denis. 2009. The Messiah of Shiraz: Studies in Early and Middle Babism. Leiden: Brill.

Momen, Moojan. 2007. Baha’u’llah: A Short Biography. Oxford: Oneworld.

Smith, Peter. 2007. An Introduction to the Baha’i Faith, Its History and Teachings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, Peter. 2004. “The Baha’i Faith in the West: A Survey.” Pp. 3-60 in Baha’is in the West: Studies in the Babi and Baha’i Religions, vol 14, edited by Peter Smith. Los Angeles: Kalimat Press.

Smith, Peter. 1987. The Babi and Baha’i Religions: From Messianic Shi‘ism to a World Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Brookshaw, Dominic Parviz and Fazel, Seena B., eds. 2008. The Baha’is of Iran: Socio-Historical Studies. London: Routledge.

Momen, Moojan. 1996. The Baha’i Faith: A Short Introduction. Oxford: Oneworld.

Momen, Wendi and Moojan Momen. 2005. Understanding the Baha’i Faith. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press.

Smith, Peter. 2000. A Concise Encyclopedia of the Baha’i. Oxford: Oneworld.

Warburg, Margit. 2006. Citizens of the World: A History and Sociology of the Baha’is in Globalization Perspective. Leiden: Brill.

Post Date:

6 May 2013

BAHA’I FAITH VIDEO CONNECTIONS