JOAQUIM SILVA VILELA TIMELINE

1950 (April 20): Joaquim Silva Vilela was born in Pocrane in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

1960: Vilela moved to the federal district surrounding Brasília with his family, the year of the new capital city’s inauguration.

1977: Vilela participated in his first juried artist salon. The following year (1978) he received a prize in the 1º Salão de Artes Plásticas das Cidades Satélites.

1977 or 1978: Vilela visited the Valley of the Dawn for the first time.

1990s: Vilela abandoned painting and began producing spirit portraits on his computer using Photoshop.

BIOGRAPHY

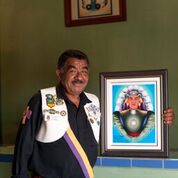

Joaquim Vilela (b. 1950) is a self-taught painter and illustrator responsible for much of the iconography of the Valley of the Dawn (Vale do Amanhecer), one of Brazil’s largest alternative religions. [Image a t right] Founded in the early 1960s by an itinerant truck driver and clairvoyant affectionately referred to as Aunt Neiva (1925-1985), the Valley of the Dawn has affiliated temples in every Brazilian state as well as Portugal, England, the United States and other international locales. Its headquarters, the Mother Temple, is located in the town of Planaltina in the federal district outside the Brazilian capital of Brasília. Vilela’s artwork is an integral part of the movement, whose Space Age cosmology synthesizes elements drawn from Christianity, Spiritism, and Afro-Brazilian religions, as well as Theosophy and other esoteric traditions.

t right] Founded in the early 1960s by an itinerant truck driver and clairvoyant affectionately referred to as Aunt Neiva (1925-1985), the Valley of the Dawn has affiliated temples in every Brazilian state as well as Portugal, England, the United States and other international locales. Its headquarters, the Mother Temple, is located in the town of Planaltina in the federal district outside the Brazilian capital of Brasília. Vilela’s artwork is an integral part of the movement, whose Space Age cosmology synthesizes elements drawn from Christianity, Spiritism, and Afro-Brazilian religions, as well as Theosophy and other esoteric traditions.

According to Valley doctrine, all human beings are inherently mediums and Vilela asserts that his particular faculty of mediumship allows him to visualize spiritual dimensions far beyond the physical world. This process is central to his artistic production. “The artist is a visionary, an intermediary,” he said in an interview, “registering on the physical plane that which he brings from the spiritual” (Hayes 2019). The imagery that Vilela has produced over the years has influenced profoundly how Valley members imagine an alternative universe to which they orient not only their ritual practices but their lives. In making otherwise invisible spiritual realities visible, Joaquim Vilela’s work brings the Valley’s imaginary world and its complex theology to life for adherents. His renderings of the highly evolved spirit mentors central to the Valley of the  Dawn’s are prominently displayed in public and private settings and are a focal point for individual prayer and petitions for spiritual intercession. [Image at right]

Dawn’s are prominently displayed in public and private settings and are a focal point for individual prayer and petitions for spiritual intercession. [Image at right]

Vilela was born in 1950, one of nine children in a devoutly evangelical Christian family in Pocrane, a small town in the interior state of Minas Gerais. From an early age he displayed an aptitude for art and wrote and illustrated his own comic books inspired by his love of science-fiction adventure tales. He was captivated especially by the futuristic technology depicted in Flash Gordon comic strips and considers its creator Alex Raymond a visionary who foresaw things that would only be invented generations later. Vilela’s early artwork often featured fantastic creatures, beings glimpsed in dreams or conjured by the restless mind of a child obsessed with stories of superheroes and interstellar space travel. Even as a small boy Vilela knew that his fantasy world was better kept private since such fanciful creations had no place within the rigidly conservative faith of his parents, for whom there was only God and the devil.

Although it was only later that he fully understood this, Vilela reported that his art “always had a spiritual influence” (Hayes 2019). Images of “inferior beings, suffering spirits, other dimensions and planes of existence” frequently appeared in his early works. Vilela attributes this to a precocious mediumship, which manifested as “extremely strange and terrifying visions.” These experiences were distressing in and of themselves, but even more so because he felt that he could not tell his parents: “I suffered greatly because I was alone and I couldn’t talk about it with anyone because my parents’ religious beliefs did not permit them to even speak of such a thing. Because if I said anything I was excommunicated.” He was particularly afraid of angering his father, who “would give me beating and say that I was inventing things” (Hayes 2019). Drawing and painting offered the young Vilela a way to objectify and assimilate these experiences.

In 1960, Vilela’s family moved to the new federal district where the Brazilian government was constructing the new capital city of Brasília. Like thousands of other Brazilians, they were inspired by President Juscelino Kubitschek’s vision for a new, modern Brazil. And, like many of these new migrants, the family settled in one of the nondescript satellite cities ringing the capital.

As a young man Vilela got a job at a local print shop and practiced his own art on the side. He says that when a customer offered him a lot of money for one of his paintings, he was emboldened to quit the print shop in order to pursue his dream of being an artist. He vowed to never work again for someone else’s gain, although it would be some time before he was able to fully realize that goal. In 1977, Vilela began to enter his work in local juried artist exhibitions and won multiple prizes over the years.

Around the same time that he participated in his first exhibition, Vilela was approached by a friend about doing some illustrations for Aunt Neiva, a well-known spirit healer in the area. Like many others at that time, he had an unfavorable impression of the Valley. “We thought it was just a pack of crazies,” he explained, “that whole thing about the spirits was seen very negatively.” But he needed the money so he agreed to meet Aunt Neiva.

And it was very interesting because she said ‘do you think you can paint these entities for me?’ And I said ‘yes I can.’ I had no idea what she was talking about at that time. But I said, ‘sure, I can do it.’ I hoped I could do it. Because I’ve never shied away from a challenge, I like a challenge. So then she told me to prepare a large canvas, two meters long by one meter wide, because I needed to paint the spiritual planes. And I had absolutely no notion of what she was talking about, I had never heard of the spiritual planes. But I told her that I could paint them. I prepared

the canvas and brought it with me and we started the painting. Seventeen days later the painting, which she named ‘Os Mundinhos’ [the Beloved Worlds], was finished” (Hayes 2019). [Image at right]

She called it Os Mundinhos because the painting encapsulates all of the fundamentals of our Doctrine,” Vilela explained. “You have all of the dimensions of existence, the spiritual planes, the origins of everything represented in the painting. It is remarkable. And I was able to paint this painting in seventeen days. When I finished it she was very excited and called everyone over to see it and told them ‘finally, the person whom Father White Arrow [Aunt Neiva’s spirit guide] has promised me for 2,000 years has arrived.’ It was me. She had been waiting for 2,000 years for me to help her complete her work. (Hayes 2019).

It was Aunt Neiva’s great dream to have this painting,” Vilela affirmed. “Because it’s one thing for her to say to someone, ‘look, the spiritual world is like this or like that.’ It’s another thing for her to show them. Because by experiencing something visually the human being can understand with much more facility, a person can enter into the image and travel there directly in their mind. (Hayes 2019).

Os Mundinhos was the beginning of a synergistic collaboration between the Vilela and Aunt Neiva that lasted until the latter’s death in 1985.

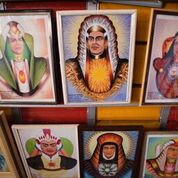

As the official illustrator of the Doctrine, Vilela worked to transform Aunt Neiva’s on-going spiritual visions into a body of religious artwork that today comprises hundreds  of works in various formats and media. Most of the iconographic representation in the Mother Temple and its surroundings are by Vilela’s hand and include paintings of highly evolved mentor spirits, as well as large (up to nine-meter high), two-dimensional images of figures important within the movement like Jesus Christ and Yemanjá, the Afro-Brazilian goddess of the sea. [Image at right] Vilela’s illustrations also adorn doctrinal literature and badges worn on the uniforms worn by members working in the temple. Vilela reproduces and sells his artwork in the form of stickers, post cards, prints, and t-shirts, which can be found in homes, hotels, restaurants, and public places throughout the small town that encircles the Mother Temple.

of works in various formats and media. Most of the iconographic representation in the Mother Temple and its surroundings are by Vilela’s hand and include paintings of highly evolved mentor spirits, as well as large (up to nine-meter high), two-dimensional images of figures important within the movement like Jesus Christ and Yemanjá, the Afro-Brazilian goddess of the sea. [Image at right] Vilela’s illustrations also adorn doctrinal literature and badges worn on the uniforms worn by members working in the temple. Vilela reproduces and sells his artwork in the form of stickers, post cards, prints, and t-shirts, which can be found in homes, hotels, restaurants, and public places throughout the small town that encircles the Mother Temple.

Since Aunt Neiva’s death, Vilela’s artistic production mostly has been devoted to creating commissioned portraits of Valley members’ individual spirit guides, using a form of mediumship he calls psycho-pictography. “Psycho-pictography is a grand fusion of psychic structure, or mediumship ability, with the knowledge of drawing,” he explained. “You have to have the technical ability to transcribe what you are visualizing and you have to have equilibrium so that you don’t lose yourself in the process of registering it.” The process begins when a client tells Vilela the name of their spirit mentor. “Once I have the entity’s name,” he explained, “I become a psychic antenna,” able to open a channel into otherwise invisible realities beyond the physical plane (Hayes 2019). [Image at right]

2019). [Image at right]

According to the Doctrine, innumerable “entities of light” work with Valley members as spiritual guides and mentors. Together they form the Indian Space Current, a collective of beings who are so evolutionarily ahead of humans that they have advanced beyond the material plane and exist as pure energy or spirit. “They inhabit dimensions that we cannot even fathom,” Vilela said. “They are voyagers from the stars, creatures who come from another intergalactic system” (Hayes 2015). Because they exist outside of the physical realities of the terrestrial world, these cosmic beings must take on a particular “roupagem,” or material form, in order to interact with humans. These material forms are the subject of Vilela’s portraits. Vilela sees this work as a vital part of his mission and keeps his prices affordable so that his spirit portraits are accessible to all Valley members.

For many years his preferred medium was oil, but in the late 1990s Vilela abandoned oil painting all together and embraced digital technology, developing ways  of using Photoshop to create his portraits. The computer, according to Vilela, gives him “the opportunity to express myself through the utilization of an absolutely innovative and futuristic technology, which offers me tools like: paintbrushes, rulers, masks, erasers, line removers, airbrushes, sixty-two million colors of light, along with textures and much more” (Vilela 2002). Vilela initially encountered resistance among some Valley members, who felt that the digital portraits tended to look alike and suspected that the artist was using a computer program to create them. He scoffs at this notion. “It’s a lack of knowledge, including of the technique, which is a whole thing by itself. You have to know the technique….The machine offers you all of the basic elements to work, but it’s not alive, it doesn’t have a soul, it doesn’t have the faculty of mediumship to materialize an entity on the screen” (Hayes 2019). [Image at right]

of using Photoshop to create his portraits. The computer, according to Vilela, gives him “the opportunity to express myself through the utilization of an absolutely innovative and futuristic technology, which offers me tools like: paintbrushes, rulers, masks, erasers, line removers, airbrushes, sixty-two million colors of light, along with textures and much more” (Vilela 2002). Vilela initially encountered resistance among some Valley members, who felt that the digital portraits tended to look alike and suspected that the artist was using a computer program to create them. He scoffs at this notion. “It’s a lack of knowledge, including of the technique, which is a whole thing by itself. You have to know the technique….The machine offers you all of the basic elements to work, but it’s not alive, it doesn’t have a soul, it doesn’t have the faculty of mediumship to materialize an entity on the screen” (Hayes 2019). [Image at right]

Since going digital, all of Vilela’s work is created using Photoshop on a desktop computer and printed at his studio steps away from the Mother Temple. There he does a brisk business selling imagery in various formats as well as his  commissioned portraits. [Image at right] Also for sale are numerous books that Vilela has authored on spiritual and other topics.

commissioned portraits. [Image at right] Also for sale are numerous books that Vilela has authored on spiritual and other topics.

Although the computer was “an amazing advance” for Vilela’s artwork, he is now thinking about the next step: “I dream of the time that I will have holography in my hands, working with holography. So I am thinking in 3-D: the idea that you can create an image that can be projected as an electro-magnetic field. Can you imagine arriving at a temple and encountering an image that is three meters in height, made of light, color or energy? Projected as an electro-magnetic field? It will be an enormous advance and I believe that it will be a new era for us….Do you see what I am saying? Suddenly I can create a holographic image and, who knows, maybe even provide a portal, a concrete manifestation of an entity. Which is amazing…today this is fictional for us but it is very important for our evolution.” He concluded: “I believe that I’ve always been a little ahead of my time and I still have a lot to explore” (Hayes 2019).

Vilela’s view of reality, while affirming Valley doctrine, also goes beyond it in certain ways. He has explored his convictions about energy and the extraterrestrial dimensions of existence in a series of self-published books with titles like Spirituality: The Riddle that Psychoanalysis and Neuroscience Can’t Unravel (Espiritualidade: O Enigma que a Psicanálise e a Neurociência não Conseguem Decifrar) (Vilela 2012) and From the First Atom to Eternity (Do Primeiro Átomo à Eternidade) (Vilela, n.d.). He illustrated important events and figures in Brazilian history in a book of digital artworks called Brasil: 502 Anos de Vida, Formas e Cores (Vilela 2002).

With their saturated colors, simple lines, static poses, and frontal perspective, Vilela’s images recall traditions of naïve or folk art and express a style more influenced by science fiction and superheroes than movements in mainstream or contemporary art. [Image at right] Like the Valley of the Dawn itself, Vilela’s work draws freely from esoteric and mass-media sources, mixing elements from Theosophy, Spiritualism and various other religions present in Brazil with ideas and images prevalent in adventure fiction, popular Spiritualist literature, comic books, and television serials. The end result is a kaleidoscopic, yet cohesive universe that blends a contemporary discourse centred on science and technology with an esoteric metaphysics.

With their saturated colors, simple lines, static poses, and frontal perspective, Vilela’s images recall traditions of naïve or folk art and express a style more influenced by science fiction and superheroes than movements in mainstream or contemporary art. [Image at right] Like the Valley of the Dawn itself, Vilela’s work draws freely from esoteric and mass-media sources, mixing elements from Theosophy, Spiritualism and various other religions present in Brazil with ideas and images prevalent in adventure fiction, popular Spiritualist literature, comic books, and television serials. The end result is a kaleidoscopic, yet cohesive universe that blends a contemporary discourse centred on science and technology with an esoteric metaphysics.

IMAGES**

** Clickable enlargements are available for all of the images in this profile.

Image #1: Joaquim Vilela. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #2: Quadro. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #3: Os Mundinhos. Courtesy of Joaquim Vilela.

Image #4: Yemanjá. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #5: João Nunes. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #6: Vilela at Work. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #7: Loja. Copyright Kelly E. Hayes.

Image #8: Guides. Copyright Márcia Alves.

REFERENCES

Hayes, Kelly E. 2015. Interview with Joaquim Vilela, July 15. Vale do Amanhecer, Brazil.

Hayes, Kelly E. 2019. “I am a Psychic Antenna: The Art of Joaquim Vilela.” Black Mirror, Elsewhere 2:144-77.

Vilela, Joaquim. n.d. Do Primeiro Átomo à Eternidade. Brasília: Self-published.

Vilela, Joaquim. 2002. Brasil: 502 Anos de Vida, Formas e Cores. Brasília: Self-published.

Vilela, Joaquim. 2012. Espiritualidade: O Enigma que a Psicanálise e a Neurociência não Conseguem Decifrar. Brasília: Self-published.

Post Date:

4 November 2019