BALLINSPITTLE TIMELINE

1985 (July 22): A group of five people who stopped to pray at the Ballinspittle grotto claimed to have seen the statue of Our Lady breathing and or moving to and fro.

1985 (July 24): A police sergeant went to check out possible statue movements and reported that he saw the statue move vigorously.

1985 (July 25): The Cork Examiner reported that “hundreds” were now praying at the Ballinspittle grotto.

1985 (July 31): The Bishop of Cork and Ross, issued a statement urging restraint on the part of visitors to the grotto.

1985 (August 1): Catherine (“Kathy”) O’Mahony and the Ballinspittle apparition were featured on a primetime television news broadcast.

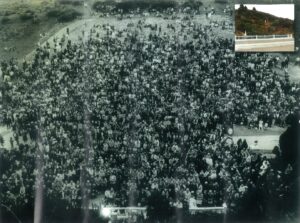

1985 (August 2): A Cork city newspaper estimated the number of people gathering at the Ballinspittle grotto each evening to be around 10,000.

1985 (August 15): Police estimated the number of people who gathered at the grotto for the Feast of the Assumption was 15,000.

1985 (September 18): A national newspaper reported claims that a deaf woman was “cured at statue” in Ballinspittle.

1985 (October 8): It was estimated in the press that since the time of the first reports of the Ballinspittle apparition the grotto had received 600,000 visitors.

1985 (October 31): The statue erected at the site was attacked and damaged.

1985 (November 8): The repaired statue was returned to the grotto

1985: The number of pilgrims attending the site had begun dwindling toward the end of the summer school holidays and decreased further with the coming of winter.

Post 1985: The numbers attending in the years after 1985 rarely reached more than 100.

2015: There was renewed interest in the events at Ballinspittle on the thirtieth anniversary of the 1985 events.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

There is a long history of divine apparitions in Ireland. In the second half of the twentieth century, for example, local people told of claims of “moving statues” similar to those that would be made later at Ballinspittle. [Image at right] For example, such reports were made by two priests in the early 1970s; by two children in 1981 and 1982; by a cousin of Catherine O’Mahony in 1982; and in 1983 by two of the girls at the centre of the 1985 claims, Helen and Claire O’Mahony (Ryan and Kirakowski 1985:11).

There were numerous apparitions associated with the Marian shrines that were established in many parishes to celebrate the Marian Year of 1954. It has been estimated that there were about thirty such occurrences, many centering around the Virgin Mary, but some that involved other saints as well.

Some observers (Mulholland 2009, 2011) have connected this series of apparitional events to conditions in Ireland during this time (Quinlan 2019):

The summer of 1985 was an unusually difficult one for Ireland — 329 people were killed in the Air India disaster in July when an airplane was blown up by a bomb crashing into the Atlantic Ocean while in Irish airspace. Meanwhile Ireland was in the midst of a crushing economic recession. High unemployment figures and mass emigration left families and communities struggling, while traditional church teachings were being challenged as the divorce and abortion referendums were contested.

The Marian grotto in Ballinspittle was one of the most prominent apparitional events of this time. In 1985, claims of an apparition at that site attracted so many visitors that it “looked set to become Ireland’s second national Marian shrine” (Allen 2014:227). However, though it also attracted a great deal of national and international media attention, the Ballinspittle apparition was just one in a spate of similar apparition claims from numerous other locations that collectively soon came to be known as the “moving statues.”

The group that claimed to see the Ballinspittle statue move on July 22, 1985, was comprised of Christopher Daly and his wife “Pat” along with their sons John and Michael and their neighbour Catherine  (‘Kathy’) O’Mahony and her two daughters, Helen and Claire. [Image at right] Two years before that, in 1983, Helen and Claire had made a similar claim.

(‘Kathy’) O’Mahony and her two daughters, Helen and Claire. [Image at right] Two years before that, in 1983, Helen and Claire had made a similar claim.

The events of July 22, 1985 began when seventeen-year-old Claire was overheard telling John Daly that the statue was moving. When John responded saying that he could see it moving, Catherine O’Mahony and the rest of the group said they could also see it moving. They told some passers-by who also saw it move or change in some way. Word spread, and later that night about thirty other people claimed to see some kind of movement, a transformation or a change in the statue’s appearance (Ryan and Kirakowski 1985:10-13).

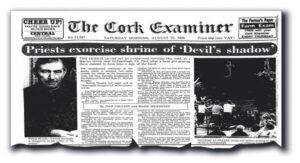

On approximately July 24, a police sergeant from the locality visited the site and reported that he too saw the statue move with such vigour that he feared it would topple over. Sergeant Sean Murray is said to have added greatly to the credibility and increased the attention of the public’ (Ryan and Kirakowski  1985:15). The following day The Cork Examiner carried a front-page story reporting that “hundreds” were now praying at the Ballinspittle grotto. [Image at right]

1985:15). The following day The Cork Examiner carried a front-page story reporting that “hundreds” were now praying at the Ballinspittle grotto. [Image at right]

In the first days of August media coverage of the Ballinspittle apparition intensified. Catherine O’Mahony and the Ballinspittle apparition were featured on primetime television news broadcast. A newspaper in Cork estimated daily visitation to the grotto to be around 10,000.

The site gained additional visibility in September when a media report claimed that a “deaf woman” had been healed. In early October, it was estimated in the press that total visitation at the site was around 600,000. The statue at the site was attacked by men armed with an axe and hammer and supported by another man who took photographs and  accused the gathering of idolatry. Repairs to the statue were made rapidly, and it was repositioned at the grotto. [Image at right]

accused the gathering of idolatry. Repairs to the statue were made rapidly, and it was repositioned at the grotto. [Image at right]

The auspicious beginning of the Ballinspittle apparition site did not last, however. Toward the end of the summer school holidays, visitation began to decline. Further declines occurred with the arrival of the winter months. Visitation rates never rebounded and subsequent daily visitation numbers rarely exceeded 100. There was renewed interest in the events at Ballinspittle in 2015 on the thirtieth anniversary of the 1985 events, with prayers and processions taking place for a week (Egan 2015).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

All of the moving statue visionaries, their supporters, and the vast majority of those who visited the apparition sites were brought up in the Roman Catholic faith. So, it is reasonable to assume that the great majority of them believed in the core doctrines of the Catholic Church. Belief in the possibility of divine intervention was fundamental to that belief system, and the moving statue visionaries and pilgrims were familiar with the apparition stories from Knock, Lourdes, Fatima and Medjugorje. Some pilgrims also believed in the possibility of miraculous cures, and Catholic Church officials like Bishop Michael Murphy were careful not to disparage such beliefs when advising “extreme caution” regarding the claims of the Ballinspittle and other visionaries (The Cork Examiner, July 31, 1985).

Each Marian shrine has a vernacular theology of its own, which devotees situate into the wider theology of the Catholic Church; that is to say that the theologies of these shrines are hybrids of vernacular and institutional beliefs and doctrines. The devotional poetry and prayers reflect the vernacular theology the shrine’s devotees create (Beesley 2000; Sigal 2005; Morgan 2010; Wojcik 1996). This is exemplified in a prayer recited by the grotto committee after the recitation of the rosary at the grotto. It is simply known as “Evening prayer.” The opening lines immediately capture the beliefs about the moving statue and the Ballinspittle Madonna teased out above:

Night is falling dear Mother, the long day is o’er And before your loved image I’m kneeling once more,To thank you for keeping me safe thro’ the day,To ask you this night to keep evil away (Grotto Committees 2015:59)

There are continuing experiences of a moving statue at Ballinspittle, although they are few in number and no longer draw significant media coverage (Allen 2015: 93).

Some of the visionaries and some of the pilgrims at the Ballinspittle grotto may have received divine messages of a personal nature, but none of them claimed to have received any kind of prophetic message or warning for relaying to the faithful or to the world at large. However, some  people interpreted the actual apparitions as being a message in and of themselves. As the grotto committee [Image at right] put it in their 2015 booklet: ‘Many believe that it was a call and invitation to prayer and most especially to pray the Rosary for peace and harmony in the world’ (2015: 52). Hence, in a chapter headed “The Message of Ballinspittle Grotto” the committee explained its own raison d’être as being to “spread devotion to Our blessed lady” (2015: 53). But closer to the time of the 1985 apparitions other meanings were being offered up. For example, as Ryan and Kirakowski noted, on August 23 the Cork Examiner published a letter from a woman who claimed to have seen the Ballinspittle statue moving and who interpreted it as being Our Lady calling ”her children from sin to save their immortal souls” and as a warning against “The rejection of the Blessed Virgin by the atheist mods…”. Then, on August 26, Time Magazine quoted the Ballinspittle post mistress, Marie Collins, as having explained the apparitions as being “a sign to prepare us for the end of the world” (Ryan and Kirakowski 1985:23, 30). It should be noted, however, that warnings of an impending global catastrophe had been issued by a couple of youthful visionaries at the Mount Melleray grotto over a week before, on August 16, 1985 (Allen 2014:123-24).

people interpreted the actual apparitions as being a message in and of themselves. As the grotto committee [Image at right] put it in their 2015 booklet: ‘Many believe that it was a call and invitation to prayer and most especially to pray the Rosary for peace and harmony in the world’ (2015: 52). Hence, in a chapter headed “The Message of Ballinspittle Grotto” the committee explained its own raison d’être as being to “spread devotion to Our blessed lady” (2015: 53). But closer to the time of the 1985 apparitions other meanings were being offered up. For example, as Ryan and Kirakowski noted, on August 23 the Cork Examiner published a letter from a woman who claimed to have seen the Ballinspittle statue moving and who interpreted it as being Our Lady calling ”her children from sin to save their immortal souls” and as a warning against “The rejection of the Blessed Virgin by the atheist mods…”. Then, on August 26, Time Magazine quoted the Ballinspittle post mistress, Marie Collins, as having explained the apparitions as being “a sign to prepare us for the end of the world” (Ryan and Kirakowski 1985:23, 30). It should be noted, however, that warnings of an impending global catastrophe had been issued by a couple of youthful visionaries at the Mount Melleray grotto over a week before, on August 16, 1985 (Allen 2014:123-24).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The idea of building the grotto that later became the site of moving statues began at a meeting of the Pioneer Total Abstinence Association in February, 1954. A group of parishioners chose a suitable site, and a week later three of them sought permission from the parish priest to go ahead with the work at Sand Cross, Dromdough. The site was chosen for its picturesque setting and because it had a natural rock face reminiscent of the grotto in Lourdes. [Image at right] The site was donated by Denis O’Leary. According to the Grotto Committee book, part of the hilly field across the road from the grotto was “acquired” in 1985 from Michael McCarthy, so as to accommodate the large crowds. A cabin also was erected that was used to house the public address system and served a venue for committee meetings (Grotto Committee book 2015:6-8)

As word of the 1985 apparitions drew ever-increasing crowds to the site, the 1982 committee called elections, and with Brendan Murphy as chairman the new committee took charge of organizing the crowds. They also reorganized the committee, and Fr Tom Kelleher replaced Fr Kieran Twomey CC as their spiritual director. By then the committee had around 100 other volunteers (Ballinspittle Grotto & The Moving Statue 2015:71, 74). Under the committee’s guidance, those volunteers helped organize vigils and had the assistance of the Garda traffic corps and the Red Cross while Denis O’Reilly, who helped to build the grotto back in 1954, used his position as a county councilor to lobby for road and other infrastructural improvements around the site (Ryan and Kirakowski 1985:10, 17, 18).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

From its inception, Ballinspittle faced several external sources of challenge that impacted its development and sustainability. The most important of these were competition from other Marian sites, opposition from various media sources, and opposition from Roman Catholic officials.

The 1982 committee produced a booklet containing witness testimonies as part of a campaign to have church authorities officially recognise the grotto as a place of pilgrimage (Ryan and Kirakowski 1985:17; Allen 2014:108). However, the Ballinspittle site falls within the organizational jurisdiction of the Bishops of Cork, and it has withheld any affirmation that it is a place where the Virgin Mary appeared. In the absence of official legitimation, the committee has adopted a more traditionalist stance, promoting recitation of the rosary at the grotto and by families in their homes (Allen 2015:108).

The grotto, however, remains a place where cherished practices no longer hailed by the church find a home and are readily promoted by the grotto committee. They are especially desirous to promote the family rosary, placing signs at the grotto to encourage people to recite it in their homes. The issue of agency arises out of this, and that issue has led to disputes between the committee and the local clergy in the past. The priest and the committee differ in opinions regarding the benefits of prayer at the local shrine and the intercession of Mary. For the church the grotto acts as a secondary shrine, but for the committee and pilgrims the apparitions have elevated its significance and, for some, it has become a place where the divine can be experienced without priestly intermediaries. And therein lays the crux of the problem for the clergy. If people can directly see and invoke Mary’s agency at the local grotto, then the priest’s agency becomes a lesser and secondary one at best. Media coverage of those differences ensured that they were widely known. For example, on August 16, 1985, a national newspaper reported that a priest in Ballinspittle parish had insisted that local clergy were not in any way involved in what was happening at the grotto (The Irish Press). There is also another worry for the clergy concerning what is and is not acceptable in Catholic orthodoxy and how this can be threatened and at the times flouted at the grotto, at least from the vantage point of the clergy (Allen 2015:113). These differences notwithstanding, the fact that both the 1985 and the 2015 committees had/have a priest as a “spiritual adviser” demonstrates the committees’ willingness to conform to Catholic orthodoxy.

Along with resistance from local clergy and the Catholic hierarchy, those who strove to promote the Ballinspittle grotto also had to deal with local scepticism, competing claims, and being ridiculed in the media where the economic benefits of large numbers of pilgrims was often mentioned (“The Moving Statue” n.d.). These were the main challenges facing the Ballinspittle grotto committee’s attempts to garner lay and religious support for their goal of turning the shrine into an officially recognized place of pilgrimage.

Incredulity and scepticism regarding the moving statues was evident in press reports about the phenomenon, even from those associated with the site. For example, one of the original Ballinspittle seers, the grotto committee’s assistant secretary Kathy O’Mahony, is said to have “remained puzzled as to why people willingly accepted” the apparition claims (Allen 2014:75). Another woman who had a visionary experience at the Ballinspittle grotto “was very sceptical of the phenomenon and remains so despite what she has seen and experienced” (Allen 2014: 92).

The Ballinspittle claims also affected the way in which other apparition claims were received. For example, a mother of one of the children who claimed an apparition at Rossmore grotto on August 5, 1985, is reported to have said “It was just after Ballinspittle, and we thought they were having a laugh at the locals. No way did we believe it at all” (Allen 2000:349).

Media coverage of claims emanating from some apparition sites may also have sowed doubt and confusion amongst believers. For example, on September 16, 1985, The Irish Press reported that some people had claimed to see images of the devil at a Marian shrine in Mitchelstown, Co Cork. And on August 23, 1986 The Cork Examiner reported that two priests had carried out an exorcism at a grotto near Inchigeela. Such reports undermined the credibility of apparition claims and supported perceptions of them as involving some “hysteria” (see Allen 2014: 3, 222-25, 233-36, 249).

Furthermore, when interviewed by the media and or researchers investigating the apparitions, people attending the various shrines offered alternative interpretive filters. Some offered religious explanations, and others tended towards rational explanations. Those offering rational explanations sometimes mixed them with sociological theories, such as their being a “sign of the times” or a reaction to moral decline or the secularisation of Irish society. Some interpreted them as being a reaction to the changes wrought by Vatican II, using them to criticize Vatican II and argue for theological changes. For example, in 1986, The Furrow published a paper in which Fr Joseph O’Leary held that the apparitions were a delayed reaction to the reforms of the Second Vatican Council and suggested that the whole phenomenon revealed “gaps in the theology of the institutional Church” (O’Leary 1986). As a clerical columnist with one of the two national Sunday newspapers explained them, the moving statues and related phenomenon reflected a widespread desire for “genuine spiritual experiences” and “having their emotions charged by a bit of liturgy with life in it” (See, Mulholland 2019:319).

Though the committee’s “spiritual adviser,” Fr Kelleher, was determined to dampen enthusiasm for the apparitions and thought Church officials advised caution or skepticism regarding all apparition claims (Allen 2016:109; Salazar 2008:245), television footage from the time shows that some religious personnel did participate in ritual activities at certain apparition sites. However, with reports of 10,000 people attending the Ballinspittle grotto each evening and with the proliferation of apparition claims being accompanied by increasing levels of ridicule in the media, some of the less sympathetic or indulgent clerics spoke out and took action. For example, on August 9, 1985, The Irish Press reported that some “witnesses” had been told to “shun publicity” and that a priest had told mass-goers in Asdee “that it is only those who have a weak faith that look for signs” (See. Allen 2008:358; Allen 2014:82-84, 109; Salazar 2008:242; Ryan and Kirakowski 1985:79; Vose1986:71).

The reports of a ”Scary Mary” at the Ballinspittle grotto and of devilish intrusions or satanic apparitions at other locations [Image at right] inspired fear and a “deep seated anger and disgust” amongst some erstwhile enthusiasts (Allen 2014:93-94). Reports of priests carrying out “an unapproved exorcism” at the Inchigeela shrine also caused some consternation amongst enthusiasts and drew criticism from Bishop Michael Murphy.

The Grotto Committee was well aware of the reduced but “steady trickle of pilgrims and visitors.” In the 2015 Committee Book, the authors asked: “So is the grotto at Ballinspittle and the events that took place there in 1985, still relevant in our modern, secular and materialistic society?” Their response captures their understanding of the grotto’s historical and contemporary relevance:

In an interview with Leo McMahon of the Southern Star in the year 2010, Sean Murray, then chairperson of the grotto committee said that “the legacy of the grotto continues to be Mary’s call for prayer and living the Gospel. “We do not dwell nor retract nor apologise for what took place”. That statement still holds true on the 30th anniversary of the Moving Statue. Ballinspittle is not embarrassed or ashamed of what happened in 1985. Sean is also convinced that “Our Lady was deeply concerned about what was happening in the Church at that time”. The tsunami of revelations of major scandals within the Church which have come to light in recent years has rocked the institution to its very core. Attendances at Mass and the sacraments have dwindled drastically and our society becomes more and more secular and materialistic. “In a passage from Scripture” he said “ Jesus felt the need to go to a lonely place to pray and reflect and over two millennia later many Christians feel the urge to do the same and places such as Ballinspittle grotto provide peace, healing and comfort”. (2015: 66)

IMAGES

Image #1: The statue in the grotto at Ballinspittle. The halo of 12 stars that was added to the statue in 1956

Image #2: Claire and Helen O’Mahony. Ballinspittle Grotto & The Moving Statue, p. 10. Credit Eddie O’Hare, Evening Echo.

Image #3: Pilgrims gathered at Ballinspittle in 1985.

Image #4:The damaged statue.

Image #5: The 2015 Grotto Committee.

Image #6: The Ballinspittle grotto, 1984. Photo credit, John McCarthy.

Image #7: A press report of images of the devil in Inchigeela in 1986.

REFERENCES

Allen, Michael. 2012. “From Men to Women to Children: Some Changing Paradigms in the Anthropological Understanding of Religion.” AntropoChildren. Accessed from https://popups.uliege.be/2034-8517/index.php?id=1499&file=1&pid=1347 on 10 November 2020.

Allen, Michael. 2000. Ritual, Power and Gender: Explorations in the Ethnography of Vanuata, Nepal and Ireland. New Delhi: Manohar.

Allen, William. 2014. “A nation preferring visions: Moving Statues, Apparitions and Vernacular Religion in Contemporary Ireland.” PhD Thesis, National University of Ireland, Cork.

Ballinspittle Grotto Committee. 2015. Ballinspittle Grotto & The Moving Statue. Waterford, Ireland: DVF Print & Graphic Solutions.

Beesley Arthur. 2000. “Ross finds religious belief a solace in troubled times.” The Irish Times March 4. 2000. p. 19.

Cluskey, Jim. 1985. “Hundreds pray before ‘moving’ statue’.’’ The Cork Examiner, July 25, p. 1

Collins, Dan and Mark Hennessy. 1986. “Priests exorcises shrine of ‘Devil’s Shadow’.’’ The Cork Examiner, August 23.

Egan, Casey. 2015. “Crowds Still Flock to Moving Virgin Mary Statue at Ballinspittle Three Decades On.” Irish Central, July 23. https://www.irishcentral.com/culture/craic/crowds-still-flock-to-moving-virgin-mary-statue-at-ballinspittle-three-decades-on-video Accessed 20 July 2020.

Kirakowski, Jurek and Tim Ryan. 2014. Ballinspittle: Moving Statues and Faith. Cork and Dublin: Mercier Press.

“Moving Statues.” 1985. The Irish Press, September 16, p. 1.

Mulholland, Peter. 2011. “Marian Apparitions, the New Age, and the FÁS Prophet.” Pp. 176-200 in Ireland’s New Religious Movements, edited by Olivia Cosgrove, Laurence Cox, Carmen Kuhling and Peter Mulholland. Newcastle upon Tyne: Scholars Publishing.

Mulholland, Peter. 2009. “Moving Statues and Concrete Thinking.” Accessed from http://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/1919/1/PMMoving_Statues.pdf on 10 November 2020.

O’Leary, Joseph. 1986. “Thoughts After Ballinspittle.” The Furrow 37:285-94. Accessed from https://www.jstor.org/stable/i27678262 on 10 November 2020.

Power, Vincent. 1985. “‘Moving’ statue: Bishop urges caution.” The Cork Examiner, July 31, p. 1.

Salazar, Carles. 2008. “Meaning, cognition and intersubjectivity in the experience of a religious event.” Emerging Theories and Practices in Anthropology of Religion. Accessed from https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=397206 on 10 November 2020.

Sigal, Pierre André. 2005. “Pilgrimage: Roman Catholic Pilgrimage in Europe.” In The Encyclopaedia of Religion, Second Edition. edited by Lindsay Jones. Detroit; Macmillan Reference.

7148291 Lindsay Jones (ed.) (ed.)2nded. vol. 10

Morgan, David. 2010. “Introduction.” Religion and Material Culture:: The Matter of Belief. Oxon: Routledge.

Quinlan, Áilin Stranger things: Looking back at the year the statues. 2019. Irish Examiner, April 10. Accessed from https://www.irishexaminer.com/lifestyle/arid-30916794.html on 10 November 2020.

“The moving statue of Ballinspittle grotto (Ireland 1985).” Accessed from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kZjM83wZmWw on 15 November 2020.

Vose, John D. 1986. The Statues that Moved a Nation. Cornwall: United Writers.

Wojick, Daniel. 1996. “Polaroids from Heaven: Photography, Folk Religion, and the Miraculous Image Tradition at a Marian Apparition Site.” The Journal of American Folklore 109:129-48.