MARCELINE JONES TIMELINE

1927 (January 8): Marceline Mae Baldwin was born in Richmond, Indiana.

1945: Baldwin graduated from Richmond High School.

1948: Baldwin met James Warren Jones while training as a nurse at Reid Memorial Hospital, Richmond, Indiana.

1949 (June 12): Marceline Mae Baldwin married James (Jim) Warren Jones.

1953 (June): The Joneses adopted Agnes, a nine-year-old white girl.

1954: The Joneses established their first church, Community Unity, in Indianapolis.

1955 (April): The Joneses founded Wings of Deliverance in Indianapolis.

1956: Peoples Temple, the renamed Wings of Deliverance (first incorporated 1955), was opened by the Joneses in Indianapolis.

1958 (October 5): The Joneses adopted two Korean children, Stephanie (b. 1954) and Lew (b. 1956).

1959 (May 11): Adopted daughter Stephanie Jones died in a car crash.

1959 (June 1): Marceline gave birth to son Stephan Gandhi Jones.

1959: The Joneses adopted Suzanne (b. 1953), also from Korea.

1961: The Joneses adopted James Warren Jones Jr. (b. 1960), becoming the first white couple in Indiana to adopt a black child.

1962–1964: The Jones family resided in Brazil.

1965 (July): The Jones family, along with 140 members of Peoples Temple interracial congregation, moved to Redwood Valley, California.

1967–1977: Marceline Jones worked for State of California as a nursing home inspector.

1969: Temple member Carolyn Layton began relationship with Marceline’s husband Jim Jones.

1972 (January 25): Temple member Grace Stoen gave birth to John Victor Stoen, purported to be Jim Jones’ son.

1974: Peoples Temple pioneers began clearing land in the Northwest District of Guyana, South America to develop the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project.

1975 (January 31): Carolyn Layton gave birth to Jim Jon (Kimo) Prokes, who was fathered by Jim Jones.

1977 (July): Mass exodus of Peoples Temple members to Guyana began; Marceline Jones remained in San Francisco to manage Temple operations.

1977: Marceline Jones relocated to Jonestown, and resided apart from her husband.

1978 (October 3): Marceline Jones held a press conference in the United States with attorney Mark Lane, defending Peoples Temple against charges from Concerned Relatives, an oppositional group.

1978 (October 30–November 13): Marceline’s parents Charlotte and Walter Baldwin visited Jonestown.

1978 (November 17): Marceline Jones welcomed Congressman Leo Ryan and his party to Jonestown.

1978 (November 18, morning): Marceline Jones took reporters with the Ryan delegation on a tour of Jonestown.

1978 (November 18, afternoon): Marceline Baldwin Jones died in Jonestown, Guyana of cyanide poisoning. Buried in Earlham Cemetery, Richmond, Indiana.

BIOGRAPHY

Marceline Mae Baldwin was born in 1927, the eldest daughter of Walter (1904–1993) and Charlotte Lamb Baldwin (1905–1992), and sister to Eloise (1929–1982) and Sharon (1938–2012). Her early years were steeped in the values of Richmond, Indiana’s civic-minded managerial class, with its emphasis on community and service. Her father served on the city council, representing Republican interests (Guinn 2017:47; Moore 2018a:12).

Exposure to civic service was complemented by the family’s active participation in the local Methodist community. Marceline’s early religious education emphasized a “liberal social creed,” and she embraced the service aspect of this creed, volunteering her time to sing during church services. She also used her musical talents to benefit those outside of her church community, forming an outreach program with her  sister Eloise and a youth group friend; the group performed music for the local hospital and nursing homes (Guinn 2017:48). Eloise described her sister as “always helping others” (Lindsey 1978:20). And in reflecting on her daughter’s character, Charlotte Baldwin noted that Marceline “was always for the underdog,” citing as evidence Marceline’s donation of a portion of her first nursing paycheck “to a local widow with 10 children” (Lindsey 1978:20).

sister Eloise and a youth group friend; the group performed music for the local hospital and nursing homes (Guinn 2017:48). Eloise described her sister as “always helping others” (Lindsey 1978:20). And in reflecting on her daughter’s character, Charlotte Baldwin noted that Marceline “was always for the underdog,” citing as evidence Marceline’s donation of a portion of her first nursing paycheck “to a local widow with 10 children” (Lindsey 1978:20).

After high school, Marceline trained as a nurse at Reid Memorial Hospital in Richmond, Indiana. [Image at right] Her choice of vocation reflected her social commitment to service, but it also reflected her desire to see more of the world than her small Indiana town. Initially she had planned to relocate to Kentucky with her cousin Avelyn, who also worked at Reid. But she changed her mind when she met James (Jim) Warren Jones (1931–1978), who became her future spouse and with whom she would collaborate to found Peoples Temple (Moore 2012; Guinn 2017:48–49).

Marceline made Jim’s acquaintance when she requested an orderly to help with dressing a corpse for delivery to a funeral home. The orderly who responded to the call was Jim, and he impressed her with his attitude toward his work: serious and compassionate (Jones “Interview” n.d.:5; Jones and Jones 1975).

Marceline and Jim were married on June 12, 1949 in a double ceremony with Marceline’s sister Eloise and  her betrothed, Marion Dale Klingman (Double Nuptial Rite 1949:7). Jones was eighteen, and Marceline was three years his senior; unbeknownst to both, they were third cousins (Young 2013). The Baldwin family’s stature [Image at right] in the community warranted a lengthy write-up of the wedding in the local newspaper (Guinn 2017:52; Double Nuptial 1949:7). The guests included the mayor and several members of the city council (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:36).

her betrothed, Marion Dale Klingman (Double Nuptial Rite 1949:7). Jones was eighteen, and Marceline was three years his senior; unbeknownst to both, they were third cousins (Young 2013). The Baldwin family’s stature [Image at right] in the community warranted a lengthy write-up of the wedding in the local newspaper (Guinn 2017:52; Double Nuptial 1949:7). The guests included the mayor and several members of the city council (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:36).

The Jones family developed alongside their ministry. Between 1953 and 1977, they added seven children, six of whom were adopted, to their fold. Their family unit contracted and expanded over the years as Jim and Marceline unofficially took in others (for example, two Indiana women, Esther Mueller and “Goldie”) (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:47), and Bonnie Thielman (Thielman and Merrill 1979:12), the daughter of a missionary whom the Joneses met while in Brazil.

Marceline’s relationship with Jim fundamentally shifted her views on what it meant to fight for the side of what is good and right. As she tells it, “[t]he most rebellious thing I ever did before I met Jim was to walk in and say I was going to vote a straight Democratic ticket in front of a group of people who knew my father was a dyed in the wool Republican” (Jones “Undated” n.d.:2). The cumulative effect of their relationship convinced Marceline that living by example was essential to doing good in the world, even if the strategies employed, such as public protest, put her at odds with the social rules with which she was raised.

Over the years, her relationship with her husband would be tested publicly and privately. During a family dinner at the Baldwin’s house, Marceline’s mother made a remark against interracial marriage, and Jim stormed from the house, telling Marceline he would never return, leaving her to follow him. On separate occasions, he threatened suicide (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:37) and ending the marriage (Guinn 2017:53–54) if Marceline did not reject her Methodist belief in a Christian god and relinquish attending practices, such as praying. Later, their relationship would be complicated by his sexual relationships with other women, relationships that were rationalized through the doctrine and hierarchy of Peoples Temple (Maaga 1998:72–73; Abbot and Moore 2018). If Marceline wanted to be with her husband, she would have to take him on his terms, and she did (Guinn 2017:53).

Marceline dedicated herself to a field in which she would work until her death: healthcare. During Jim and Marceline’s engagement, her work as a nurse helped to financially support Jim while he pursued his university degree (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982: 35). Her nursing skills took her to operating rooms (Jones “Undated” n.d.:2) in a Bloomington, Indiana hospital and later, in Indianapolis, Indiana, to a hospital’s children’s ward (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:36). By 1956, she had assumed lead responsibilities for managing care at a racially integrated nursing home, Peoples Nursing Home. By 1960, a second home, the Anthony Hall Nursing Home, came under her oversight (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:56; “New Nursing Home” 1960:3).

When Peoples Temple moved west, Marceline worked for a decade with the California Board of Health (Turner 1977:8), part of that being her time as a state health inspector for nursing homes in California (Tipton 2002). The salary she earned as a State of California employee was placed into a legal defense fund for her husband (Turner 1977:8). She also helped the Temple build a profitable collection of sixteen care homes catering to the needs of the elderly, the mentally disabled, and foster children (Moore 2018b).

Marceline’s final months were spent in Guyana, South America, where she coordinated the medical facilities at Jonestown (“Agricultural Mission” 2005; Guinn 2017:386). Her work in nursing overlapped with Temple endeavors and contributed substantially to the Temple’s success (Maaga 1998:77; Moore and Abbott 2018), but Marceline’s career as a medical professional, which spanned two decades of work in challenging settings and a variety of capacities, was significant in its own right.

She also had a direct hand in ministry-building alongside her husband. Indeed, it could be said that it was Marceline’s guiding hand, which directed Jim’s gaze toward the social-justice tenets of Methodism, that set his sights on becoming part of the clergy (Hall 1987:24; Moore 2018a:12; Guinn 2017:56). Within the span of three years, Marceline and Jim founded three congregations: Community Unity (1954), Wings of Deliverance (1955), and finally Peoples Temple (1956) (Hall 2987:43–44). Marceline states (Jones Recollection n.d.) that she encouraged Jim to go the “Oral Roberts” route (i.e., become a traveling faith healer who drew large crowds), but he wouldn’t do that.

Instead, their ministry gained traction locally through a powerful combination: Jim’s faith healings, coupled with a responsiveness to members’ needs and a commitment to the social gospel. In the early 1960s due to concerns about nuclear fallout, a concern likely stoked by an article in Esquire, Jim considered relocating the ministry. One site noted was in Brazil, and Marceline, Jim, and the Jones’ children spent time there on a scouting trip (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:77–8). While they were away, the Temple remained in Indiana under the pastoral care of others appointed by Jim.

But the trip to Brazil was unsuccessful for a number of reasons, and the Joneses returned to Indianapolis and began rebuilding the congregation, which had diminished in their absence. They also scouted alternative locations for a new home, and the most promising was in Redwood Valley, California. Marceline traveled west to confirm its appropriateness for the congregation’s needs, and she purchased the property where the new Peoples Temple building would later stand (Beam 1978:21). From the site in northern California, the ministry marched down the coast to San Francisco and Los Angeles, and eventually reached Guyana, a country neighboring Venezuela. Marceline remained in charge of San Francisco temple operations in California until October 1977, when she joined the nearly 1,000 Temple members who had relocated to the Temple’s agricultural project in Guyana (Guinn 2017:385).

Family was especially important to Marceline. [Image at right] Surviving son Stephan Jones describes her “not an activist, let alone a revolutionary” but instead as “a wife and mother and daughter” whose work and attention “extended beyond her immediate family” (2005). Despite Marceline’s break with her Methodist upbringing, she always maintained a steady relationship with her parents that included in-person visits and even collaborative work on Peoples Temple care homes (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:56). Her final contact with her parents was close to her death; she personally escorted her parents from Richmond, Indiana to Guyana in November 1978. Her parents returned to their home only days before the deaths at Jonestown (Beals et al. 1979).

Marceline died of cyanide poisoning in Jonestown on November 18, 1978. Her remains are interred at Earlham Cemetery, Richmond, Indiana.

TEACHINGS/DOCTRINES

Peoples Temple doctrine changed over time; the Christian discourse that influenced Temple doctrine early on was eventually put aside in favor of communalist political theories (Hall 1987:19–28). Temple doctrine, however, found coherence in its apostolic socialist outlook. Apostolic socialism was a term coined by Jones in response to his reading of Acts. Two passages are especially relevant: Acts 2:44-45 and Acts 4:32-35 (Moore 2018a). Both passages speak to the Temple’s larger goal of freeing people from the oppressions experienced by many who live in individualistic, capitalist culture.

Actively fighting against oppressive structures was a foundational aspect of Temple doctrine (Moore 2018c). In contrast to “do-nothing” Christianity (a frequent target of Jim’s sermons), Temple teachings urged members to take action against injustice, a quality that Temple member Thielman recognized in Marceline as “loving action” (Thielman and Merrill 1979:25). The injunction against individualism was extended in the Temple to include a broad focus on self-sacrifice for the common good, especially in the battle against race-, class-, and sex-based discrimination (Chidester 2003:52). Jim was accepted as the “embodiment of Divine Socialism,” which in his calculus meant he was, as a result of word and deed, a physical manifestation of god (Moore 2018ab; Chidester 1991:53). As Maaga (1998:68) notes, “to love God’s justice here on earth was to love Jim Jones; to be loyal to socialist values was to be loyal to Jim Jones. Any betrayal of Jones thus became a betrayal of the community and all it stood for.”

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Peoples Temple rituals and practices, which as a whole aimed at dismantling individualistic, capitalist thinking in members and cultivating loyalty to the group and to Jim as the group’s leader, have been explored in detail by Hall (1987), Chidester (1991), and Moore (2018a, 2012). For the purposes of summary here, we can organize significant rituals and practices under several types of action to which Marceline contributed significantly in her role as Mother of the Temple. (Jim Jones was called Father or Dad, and Marceline was called Mother by Temple members.)

One type of action that encompasses a range of the Temple’s rituals and practices was that involving self-confession, condemnation and/or praise of other members, and atonement for transgressions. Two significant practices were the use of catharsis sessions and Peoples Rallies. Catharsis sessions were self-criticism meetings lasting for several hours; all members with more than a superficial connection to the Temple attended these meetings (Moore 2018a:36). Temple apostates describe the abuse, both physical and emotional (Kilduff and Tracy 1977), that was at times a part of the catharsis sessions. Peoples Rallies continued the catharsis tradition in Jonestown (Beck “Rallies” 2013). Both practices aimed at managing members’ behavior through a combination of public confession, member-on-member reporting, and punishments or praise doled out by Jones, sometimes in coordination with recommendations from others (Moore 2018d; Moore 2018a:32).

Punishments helped members atone for their transgressions against the community. Marceline is credited with the shift away from corporal punishment in Jonestown to the use of peer pressure (Kilduff and Tracy 1977; Stephenson 2005:79–80). Based on Marceline’s input, Jim developed the Learning Crew (Guinn 2017:359). Temple members were assigned to the Learning Crew for minor infractions against community norms, and they were tasked with undesirable but necessary work, such as digging ditches or trimming grass alongside community walkways by hand. While serving out their punishment on the Learning Crew, they were personae non gratae to the rest of the community. In addition, they were beholden to a supervisor from whom they had to ask permission for basic activities like “visiting the bathroom or drinking water” (Moore 2018a:48).

Marceline also impacted the protocol associated with another of Jonestown’s punishments, the “sensory deprivation chamber,” a 6’x4’ cubicle in which a transgressor could be isolated individually for up to a week. She insisted that the vital signs of those placed in the chamber be regularly monitored (Moore 2018a:74). Her authority as a part of the medical community in Jonestown and her status as Mother likely permitted her voice to be heard on these matters.

Another type of action in the Temple was oriented toward affirming the loyalty of members to the group and to Jones as the group’s leader. Included here are large-group practices such as the suicide drills (Moore 2012), “going communal,” composing “Dear Dad” letters, signing Temple forms that affirmed Jim’s authority, and using Temple honorifics for Jim (Father, Dad) and Marceline (Mother, Mom). As a whole, these practices allowed members to affirm that they worked on behalf of the group and acknowledged Jim’s status as the group’s leader.

Marceline contributed content to several primary texts, written for Temple members and/or the general public, that served to affirm Jim’s greatness. Her “Undated Recollections,” “Jim Jones . . . as seen through the eyes of those HE LOVED,” and a letter addressed “to whom it may concern” are three examples of affirmative texts. She also composed private correspondence to her husband that affirmed her belief in him (“The Words of Marceline Jones” 2013). Her production of Temple texts, especially those that documented Temple stories about Jones’ selflessness, commitment, and abilities, was significant not just for what was said, but also for the fact that Mother said it.

Chidester’s (1991:52) discussion of faith healing and its role in the Temple surfaces yet another category of action, which is that concerned with liberating members “from the human limitations of a dehumanizing social environment,” and Marceline made substantial contributions to this category of activity. She was directly involved in helping her husband stage his faith healings. Recollections of Temple members provide some details, such as her handling the “growths” ostensibly removed from congregants’ bodies (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:49; Harpe 2013) and her removing a freshly applied cast from woman strong-armed into claiming she had a broken bone (Thielman and Merrill 1979:78–79). Initially Jim kept from Marceline the details of how he managed the healings (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:46), but given her medical training, as well as her status as part of his inner circle (Moore 2018a:36), it seems unlikely that she was not aware that some aspects of these events, if not all aspects, involved subterfuge.

LEADERSHIP

In the Temple’s Indiana days, leadership was a cooperative endeavor between Marceline and Jim. He was the frontman and she shouldered a great deal of the administrative work (Abbot and Moore 2018). For instance, she was in charge of the Temple’s first nursing home, one of many the Temple would establish over its history, thus helping to initiate and maintain a critical line of income to support the Temple’s financial health and social-oriented mission (Moore 2018a:17; Abbott and Moore 2018). Given that her attempts to plan the Temple’s services were ignored by her husband (Guinn 2017:70), this administrative work offered a productive outlet for Marceline’s service-focused energy.

Marceline’s dedication to healthcare, especially the elder care for which the Temple was known, would become a defining feature of her public persona and her leadership in Peoples Temple (Maaga 1998:90). Her husband at times publicly mentioned her work in the context of praising her activism and critiquing a system that used people for profits (see, for example, Q255 1978). Longtime Temple member Laura Johnston Kohl describes Marceline as “a crusader” in her efforts to provide care for the elderly (Kohl 2010:30). Hyacinth Thrash, a senior citizen who was one of Jonestown’s few survivors, credits Marceline with keeping Jonestown’s medical facilities up to a high quality (1995:90).

Within the Temple, Marceline’s status was elevated and formalized the late 1950s when “Sister Jones” became “Mother Jones,” [Image at right] a change that paralleled Jim adopting the title “Father.” This name change was styled after the honorifics used by Father Divine and his wife Edna Rose Ritchings, whose Peace Mission the Joneses had visited and on whose ministry they modeled some of Peoples Temple’s efforts (Moore 2018a:16–17). “Mother” seemed to reflect the view that members had of her, as “a somewhat remote if caring and overarching mother figure” and “the compassionate heart of Peoples Temple” (Cartmell 2010).

She seemed to take this role seriously, and Temple recordings capture moments of care-filled “parenting” that speak to her concern for people’s health and well-being. These moments run the gamut from advising members not to undertake dangerous work during the day because they might make critical errors due to sleep deprivation (Q569 1975) to more substantial lessons, such as the reminding them that tough love and anger do not mean that someone does not care (Q573 n.d.). Sometimes she does make use of anger to push a point, such as when she admonishes Temple members who cannot easily see the honesty in her husband (Q955 1972), chides those who fail to back their words with action, unlike Jim (Q1057-3 1973), scolds a Temple member for making light of assassination attempts on Jim’s life (Q600 1978), and reprimands a member accused of stealing whose arm was previously healed by Jim (Q807 1978). One particular moment captures her appreciation of members’ affection for her and her role. She is being welcomed home to Jonestown with a song dedicated  to her, and she quotes a Temple member who said to her, “‘Mom, I really miss you, ‘cause when you shake your finger in somebody’s face (laughs) they know you mean it and we step to.’ And I appreciated the fact that he knew that I did it because I cared. I’m not always right, but I say it like I see it . . .” (Q174 1978).

to her, and she quotes a Temple member who said to her, “‘Mom, I really miss you, ‘cause when you shake your finger in somebody’s face (laughs) they know you mean it and we step to.’ And I appreciated the fact that he knew that I did it because I cared. I’m not always right, but I say it like I see it . . .” (Q174 1978).

Her matriarchal role gave her the rhetorical standing to bolster her spouse’s leadership efforts. When speaking to members, for example, [Image at right] Marceline often depicted herself as naively doubting Jim’s certitude, only to be reminded of his truth and power when he succeeds (for example, Q775 1973). Over and over again, she is converted to his perspective as he tackles greater challenges. Her words and reflections would no doubt have had a persuasive effect on her audience: if Mother did not believe, why would she remain? Her support reinforced his charisma.

Her status was in turn bolstered by her spouse’s laudatory references to her character. She exemplified Temple values, and she was, therefore, a role model. The times when Jim critiqued her also called out her status relative to others, for instance when he stated during a sermon that even Mother was not above reproach (Q1021 1972): “I didn’t spare Mother [a criticism], because Mother’s got to be in a position to carry principle.” He comments on her positively in comparison to the wives of “other preachers”— they are flashy, she is not — (Q162 1976); he notes that she is second closest to power, with him being first (Q568 1974); and he often referred to her with terms of endearment that carried status, such as his use of “loyal wife,” “my love,” “wife of xx years,” and “faithful companion” in reference to her (for example, Q1021 1972; Q233 1973; Q589 1978; Q591 1978).

Marceline consistently defended the Temple and Jim against perceived attacks, [Image at right] stating in one 1978 press conference that her spouse is a “man of the highest integrity” and those who have participated in defaming his character (this “man who has always been an advocate of the poor and oppressed”) will find themselves on the receiving end of a lawsuit (Q736 1978). Her support of his more challenging viewpoints, such as his belief in the power of revolutionary suicide, are present in Temple recordings, such as those made during a Jonestown White Night where she states that she will die with her husband if he were to choose that path (Q635 1978). During the same meeting, she also chastises members who do not respond with proper emotion when Jim talks about giving up his own life.

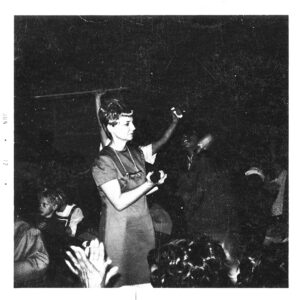

At times she delivered sermons in Jim’s absence, [Image at right] although when she did so, she indicated clearly that any insights she shared with the congregation originated with him; she was merely the conduit (Q436 1978).

The extent of Marceline’s influence and the nature of her responsibilities changed and contracted over time. This was due in part to shifts in Temple demographics and size; what started as a small, community-engaged outfit grew into a large, diverse multi-site operation requiring a complex leadership structure. Furthermore, once the Temple moved to California, it attracted a new demographic: young, educated Caucasians from higher economic classes. Many of the female recruits became part of the Temple’s administrative structure, and a select number of them became members of Jim’s inner circle of advisors. It is too simple to say that the new members usurped Marceline’s leadership responsibilities (she continued to act as a figurehead and had practical responsibilities associated with her role as a Temple officer), but in an absolute sense, she had less individual power when the group’s California ranks swelled, its projects and goals became more complex, and the leadership structure changed. Perhaps as a consequence, she seemed to prefer the company of the members who joined in Indiana (Maaga 1998:78). (See Abbot and Moore 2018 and Abbott 2017 for a comprehensive overview of women’s work and power in the Temple, including the contradictions that women faced.)

There is little to suggest, however, that the Temple membership’s view of Marceline shifted much. In Temple meetings, she was consistently referred to as “Mom” or “Mother.” As late as 1978, Jim invoked this status (“Don’t you give no shit to Mother”) when disciplining members (Q734 1978). And one Temple member, while completing a Temple-administered self-analysis writing activity, observed that should someone succeed Jim as the movement’s leader, that person could be Marceline: “An extremely strong leader is needed to keep together this kind of group. Mother is the prototype of everything next in a woman.” The same member observed that the group might not yet be “ready to follow a woman” (“FF-5 Statements” n.d.). Although Marceline was designated as a successor to Jones in one version of Jones’ will (Q587 1975), her sons were more certain about the necessity of male leadership: if Peoples Temple were to have leadership other than Jim Jones, they would fill the void. In an organization that argued for women’s rights and had female administrative leadership at the highest levels, sexism remained, with Jim Jr. noting that his father “‘talked [gender] equality but for him, it was always his sons’” (Guinn 2017:338).

Despite her loyalty to Peoples Temple and its apostolic socialist principles, Marceline was willing to engage in behavior problematic from a Temple perspective with her children’s interests in mind. She squirreled away money in a bank account for at least one of her children (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:456). She made interventions on behalf of son Stephan, who wasn’t sure that, by the time that work on Jonestown was ramping up, he wanted to be so much a part of the Temple. Stephan took a job as a valet in San Francisco, and with his mother’s help, made arrangements to live alone in an apartment (Wright 1993:75). He was unable to follow through with these plans because his father, perhaps sensing his son’s increasing distance, pushed for Stephan to relocate to Jonestown. Marceline secured a compromise from Jim that Stephan would go to Jonestown only temporarily. Once in Jonestown, however, he was there permanently (Wright 1993:75). While in Jonestown, Marceline helped the Jonestown basketball team get permission to leave the community to play with other teams; this advocacy ended up saving the lives of three Jones children: Stephan, Tim, and Jim Jr. (“Who Was On the Jonestown Basketball Team and Why Were They in Georgetown on November 18?” 2017; Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:475).

ISSUES AND CHALLENGES

The dreams that Marceline once had for her life (family, service, stability) were sidelined by her spouse’s infidelity. According to Jim, he and Marceline were both virgins when they married, and they were monogamous up until the time, thirteen years after they wed, that Jim engaged in sexual relations with a diplomat’s wife in exchange for a $5,000-dollar donation directed to a Brazilian orphanage (Q1059-2 n.d.). He made reference to this event numerous times in Temple services and meetings. But he also told people about it in more personal settings. Bonnie Thielman relates her shock at hearing the story told casually over an evening meal at the Jones’ house in California: “. . . [the Jones children] went right on eating. They had obviously heard all this before. Even Marceline didn’t blanch” (1979:47).

Jim’s strategic use of extramarital sex continued after Brazil, and he was vocal about it. These actions were justified by claims that specific members needed to be drawn closer to the cause through relations with Jones (Maaga 1998:66; Abbot and Moore 2018), that sex with Jones could lead to personal growth (FF-7 Affidavits n.d.), or, in moments of candor, that Jones just needed it (Wright 1993:72). Sex was often part of an unspoken power-sharing arrangement between Jim and members of the Temple’s leadership structure (Maaga 1998:67; Abbott 2017). At its root, though, his sexual relations with members boiled down to his desire for control (Moore 2012).

The ethics of sharing in the Temple extended to sex, and monogamy was linked with selfishness; Jim was commonly the director behind Temple relationships, arranging marriages and partnerships (Moore 2018a:35), all in the name of furthering Temple principles. During one Planning Commission meeting, he opined on sharing partners: “Perfect sharing. No more jealousy . . . . My wife wants you? You want my wife? And I love you both. Happy, happy. When you love somebody, you don’t want to hold them, you want to free them” (Q568 1974). Jones also used sex to direct people’s loyalty toward him over others, including potential mates. These sexual acts were depicted by Jim as personal sacrifices made for the cause, but they were ultimately about control (Kohl 2013).

Jim’s liaisons became common knowledge in the Temple. The most significant of these was with Carolyn Moore Layton (1945–1978), a Temple member with whom Jones openly conducted a relationship and fathered a child (Moore 2018a:60–61). The affair was justified, in part, by Marceline’s supposed inability to engage in sexual intercourse; Jim also implied that she was mentally unwell (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:122–23; Moore 1985:88). Although publicly Marceline retained her status as Jim’s wife and the movement’s Mother (one Temple member described Jim and “his dedicated wife Marceline” as “the most perfect souls in principle of any two people I’ve known” (Orsot 2013)), Jim and Carolyn would become, for all intents and purposes, a couple. Jim even brought his son Stephan with him on trips with Carolyn, as though she was, or could become, a part-time mother to his and Marceline’s children (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:123). Another liaison, that with Temple member Grace Grech Stoen, became a part of the Temple’s identity due to the custody battle over John Victor Stoen, a son supposedly fathered by Jones’ with Grace. (Grace left the Temple in 1976; John Victor died November 18, 1978.)

Marceline was deeply and negatively affected by her spouse’s relationships with Carolyn and others (Thielman 1979:100; Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:401; Maaga 1998:69). Yet in May 1974, Marceline signed a document (Marceline Jones Request 2013) requesting that Carolyn “take over the mothering responsibilities” of the Jones children in the event of Marceline’s death and “fill any void [her] absence might leave,” including the physical presence in the family home. And although the paternity of John Victor would never be definitively confirmed, in a number of ways Marceline supported Jim’s claim to have fathered the boy. The most significant was her acting as a witness on Tim Stoen’s affidavit assigning parentage to Jim Jones (“Tim Stoen Affidavit” 1972). She also reinforced her husband’s claims of paternity in comments made in public Temple settings, such as her statement that the boy’s coloring matched Jim’s more closely than Tim Stoen’s (Q638 1978) and that she supported Jim’s determination to keep John Victor in Jonestown (Hall 1987:218). Jim did not spare Marceline’s feelings on the topic of his affair with Grace. During one Jonestown White Night, he talks about having intercourse with Grace and, due to her desire for him, marrying her. He chooses not to because people would leave the Temple if he divorced Mother (Q636 1978).

By staying in the marriage, Marceline gave her husband permission to continue in his behavior and gave members permission to respect him despite his behavior. Even when confronted directly with graphic evidence of his sexual escapades, as was the case during one Planning Commission meeting, Marceline lamented not the lack of monogamy, but the fact that women of the Temple used her to get to her husband:

It’s a lonely– it’s a lonely situation. Uh, you know, as far as really having any friends, I mean people you can talk to, there’s nobody, really, usually. But you still– I– I was really Pollyannaish, and I needed the camaraderie of another woman or other women, you know, someone I could talk to. And to– the hardest thing for me to face was the fact that most women didn’t give a damn about being a friend to me, but used me to get to him. (Q568 1974)

When cases of infidelity were brought before the congregation for discussion, Marceline was apt to be forceful, urging Temple women to refuse easy relationships with men who would use them (Q602 1978; Q787 1978). At other times, she advocated for women who had been treated poorly, suggesting on one occasion that the person who cheats should move out of the couple’s shared lodgings, not the other way around (Q787 1978). Although Marceline was not the origin of these beliefs (women’s emancipation was always a stated Temple goal), it is fair to say that she took pains to remind women that they had the power to emancipate themselves and they should take it. But she was also complicit in maintaining conditions that allowed for sexual assault on members, such as the daughter of an apostate that Marceline, along with another female Temple member, attempted to bring back into the fold after the young woman had been raped by Jim (Q775 1973).

Although Marceline explored the possibility of divorce, she never pursued it because Jim threatened to separate her from her children if she left him (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:123–24; Thrash 1995:55). Nor did she find solace in a partnership with someone else (Thielman and Merrill 1979:100; Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:376). In a public statement delivered by Marceline to members of the Temple, she tells listeners that her selfishness regarding Jim, her inability to “make the adjustment to being married to a man who was also married to a Cause,” prompted him to ask her for a divorce. Consequently, she took time to reflect on this and decided that she would, without resentment, agree to “share him with people who need to relate to the Cause on a more personal level” (Wooden 1981:43–44 as cited in Maaga 1998:79). Whether or not Jim really asked Marceline for a divorce is unclear, but what is clear is that she was unable or unwilling to emancipate herself by directly confronting the problem.

We can only speculate as to Marceline’s private religious beliefs, and how she reconciled the Temple’s socialistic, and eventually atheistic, outlook with her Methodist background. As late as 1959, there is evidence of her faith in God. In a scrapbook, underneath a photo of her deceased daughter Stephanie, Marceline had written, “Dear God, help me to bear this terrible burden [the death]” (Thielman 1979:111). She struggled to work through the challenges that her husband posed to her faith. This struggle is briefly captured in a letter she wrote to Bonnie Thielman. In this letter, Marceline consoles Thielman who, at the time, was confronting her own crisis of faith brought on by People Temple doctrine. Marceline writes, “I want you to know that I feel the trauma that you are experiencing . . . . It is painful as you go through it but gloriously rewarding after the transition is made” (Thielman 1979:56–57). Her job, as was the job of all Temple members, was not just to follow the group’s leader, whoever that may be, but “to do everything you could to help that person succeed” as any good socialist would (Q569 1974).

Another challenge Marceline faced was the mental and physical deterioration of her husband. In September 1977, she helped bring an end to a six-day White Night at Jonestown. (A White Night was a type of civil defense exercise in which the entire community stood on alert pending an expected assault). This particular White Night was triggered by Jim’s paranoia regarding the possible legal removal of John Victor Stoen from Jonestown. Working over the radio from San Francisco, Marceline talked Jones down from a suicide threat, rallied his spirits by gathering supportive messages from friends and Temple allies, and contacted Guyanese officials traveling in the United States (Guinn 2017:374–76).

By late 1978, Jim’s health had deteriorated appreciably. Jim had a longstanding history of nervous exhaustion and, by 1978, he was experiencing severe pulmonary issues brought on by a fungal infection (Moore 2018a:75) and complicated by an over-reliance on drugs that taxed his body (Reiterman and Jacobs 2017:426–27). Marceline expressed concerns about this to her parents (Serial 427 1978). Along with son Stephan, she had adopted a wait-and-see attitude; wait long enough, and the situation might resolve itself through a natural succession. Her husband’s health was clearly on a downward trajectory, and his death would usher in a succession process (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:456).

This approach left Marceline in the role of mediator, which was on display when she attempted to de-escalate some of Jones’ paranoia regarding the planned visit to Jonestown by Congressman Leo Ryan, who was accompanied by reporters, Temple apostates, and family of some Peoples Temple members. Jim wanted to prevent Ryan from visiting. Marceline challenged Jim, stating that they should be proud of their hard work and that she had been the one who kept the community running, not him (Guinn 2017:423). She also persuaded Jim to cancel a White Night had planned for the evening of November 17, 1978, the day of Congressman Leo Ryan’s arrival (“Guyana Inquest” 1978).

Stephan Jones states that his mother objected to the prospect of mass suicide (Winfrey 1979) and that his mother had to be restrained when the babies were being dosed with poison (Wright 1993). At least one written text, a May 15, 1978 proposal from Marceline to Jim, argues that “asylum could be arranged” for the community’s children (Stephenson 2005:103). [Image at right] Often cited in evidence of her objection to the suicides are Jones’ words as the poisoning started at Jonestown: “Mother, Mother, Mother, Mother, Mother, please. Mother, please, please, please. Don’t– don’t do this. Don’t do this. Lay down your life with your child, but don’t do this” (Q042 1978). But Maaga’s analysis (1998:32) of that statement suggests that it’s not Marceline who Jim is referring to, but to the community’s mothers generally, of which Marceline was one. Additionally, Maaga points out that “it took Marceline Jones . . . and others in positions of responsibility and influence at Jonestown to embrace the idea of suicide for the rank and file members to have been willing to drink the poison,” as Jim himself was too debilitated to pull this off on his own (1998:116). At the same time, Guinn (2017:445), based on interviews with eyewitnesses, depicts Marceline as initially resisting the poisoning, screaming “You can’t do this!” at Jones. Jim Jones Jr. suggests that had her sons been with her, she might have been better able to stand up to her husband. Instead, she felt defeated because she thought they had already died (Guinn 2017:445–46). This may have been the case, but it is also true that two of her children, Lew and Agnes, and many others she loved were present.

It seems likely that, had her children not been held hostage, she may have divorced Jones. What is less clear is if she could have divorced the Temple. No matter what we might wonder about Marceline, we can see that she was dedicated to the cause, often at the expense of her own emotional health and, tragically, her own life. Yet her final words to her parents, delivered as they were leaving Jonestown just a few days before the deaths were: “I have lived, not just existed” (Lindsey 1978). These words suggest at least a modicum of satisfaction with the path she chose.

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGIONS

Marceline Jones played a leadership role in the rise and fall of Peoples Temple, an organization that she co-founded with her spouse. [Image at right] She is a case study of a committed female activist whose initial impulse to serve was grounded in the social justice principles of her family’s Methodist faith. She helped create an organization where “women in leadership had the authority to influence the social problems about which they were most concerned” (Maaga 1998:67), even if their authority was ultimately undermined by the organization’s leader (Abbott 2017).

It is important to remember that Jonestown bore the family name of more than Jim Jones. While there is no doubt that Jim is principally referred to in the community’s name, it is also true that without Marceline’s support, Jonestown might never have come into existence, for better or for worse. Like many women “behind the man,” Marceline provided necessary financial and emotional support to her spouse who, through her concessions, was allowed to pursue his potential at the expense of hers. Nevertheless, she was a professional in her own right and, in different ways over twenty-odd years, a key player in the development, maintenance, and destruction of Peoples Temple. In this regard she is in the company of women like Hillary Clinton and Tammy Faye Bakker, women who, in pairing themselves with unscrupulous male partners, end up undermining their own agency and that of other women, too.

Citing a series of interviews conducted by journalist Eileen MacDonald with female activists struggling to reshape society, Maaga (1998:67) draws readers’ attention to the “energy and commitment that women bring to the causes they love” (67). While neither MacDonald nor Maaga seek to glorify these women’s work, beset as it can be by violence, they do draw attention to the risks that women take when they shuck off society’s expectations and take up the mantle of revolutionary labor (Maaga 1998:67–68). Marceline should be included in the ranks of these female revolutionaries without hiding the contradictions she offers to us, a kind and loving Mother who nevertheless participated in the deaths of hundreds of people.

IMAGES

Image #1: A high school graduation portrait of Marceline Jones, 1945.

Image # 2: Marceline Jones with her parents, Charlotte and Walter Baldwin, 1971. Courtesy Jones Family Memorabilia Collection, 1962-2002; Identification number MS-0516-02-031; Special Collections, San Diego State University.

Image # 3: Marceline Jones on Beach with two of her children, Jimmy Jr. and Stephan, 1967. Courtesy Jones Family Memorabilia Collection, 1962-2002; Identification number MS-0516-02-025; Special Collections, San Diego State University.

Image #4: Marceline Jones with Microphone. Courtesy Jones Family Memorabilia Collection, 1962-2002; Identification number MS-0516-02-052; Special Collections, San Diego State University.

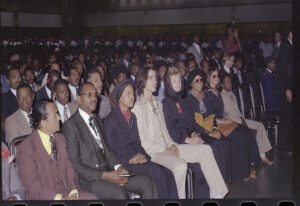

Image #5: Marceline Jones being recognized at a testimonial dinner, September 25, 1976. Standing to her right is California Lt. Governor Mervyn Dymally. Courtesy California Historical Society, Image number MS-3791_1698_22, from the Peoples Temple Publications Department.

Image # 6: Marceline Jones (black kerchief on her head) sits next to her son Stephan Jones at the Spiritual Jubilee held with the Nation of Islam in San Francisco, May 23, 1976. Courtesy California Historical Society, Image number MS-3791_1666_28, from the Peoples Temple Publications Department.

Image #7: Marceline Jones and Congregation, 1972. Courtesy Peoples Temple Collection, 1972-1990; Identification number MS0183-43-9; Special Collections, San Diego State University.

Image #8: Marceline Jones and Mike Prokes at Cuffy Memorial Baby Nursery, Jonestown, probably 1978. Courtesy Jones Family Memorabilia Collection, 1962-2002; Identification number MS-0516-04-025; Special Collections, San Diego State University.

Image #9: Marceline and Jim Jones Behind a Pulpit, probably Benjamin Franklin Junior High School, San Francisco, in the 1970s. Courtesy Jones Family Memorabilia Collection, 1962-2002; Identification number MS-0516-05-125; Special Collections, San Diego State University.

REFERENCES

Abbott, Catherine. 2017. “The Women of Peoples Temple.” The Jonestown Report, November 19. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=70321 on 5 February 2020.

Abbot, Catherine and Rebecca Moore. 2018. “Women’s Roles in Peoples Temple and Jonestown.” World Religions and Spirituality Project. Accessed from https://wrldrels.org/2018/09/27/peoples-temple-and-womens-roles/ on 2 February 2020.

“Agricultural Mission: Jonestown, Guyana 1978.” 2005. Prepared by Michael Belefountaine and Don Beck. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/3aAgricMissionOrganizer.pdf on 5 February 2020.

Beals, Melba, Nancy Faber, Diana Waggoner, Connie Singer, Davis Bushnell, Karen Jackovich, Richard K. Rein, Clare Crawford-Mason and Dolly Langdon. 1979. “The Legacy of Jonestown: A Year of Nightmares and Unanswered Questions.” People Magazine. Accessed from https://people.com/archive/the-legacy-of-jonestown-a-year-of-nightmares-and-unanswered-questions-vol-12-no-20/ on 16 March 2019.

Beam, Jack. 1978. “History of the Church in California.” Pp. 20–22 in Dear People: Remembering Jonestown, edited by Denice Stephenson. San Francisco and Berkeley: California Historical Society and Heyday Books.

Beck, Don. 2013. “Rallies.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35921 on August 5, 2020.

Beck, Don. 2005. “The Healings of Jim Jones.” The Jonestown Report 7. Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=32369 on 4 July 2020.

Cartmell, Mike. “A Mother-in-Law’s Blues.” The Jonestown Report 12. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=30382 on 12 August 2020.

Chidester, David. 1991. Salvation and Suicide: An Interpretation of Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and Jonestown. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

“Double Nuptial Rite Planned By Sisters.” 1945. Palladium-Item, June 5, p. 7.

“FF-5 Statements.” n.d. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=99911 on 30 July 2020.

“FF-7 Affidavits of Sexual Encounters with Jim Jones.” n.d. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=99934 on 30 June 2020.

Guinn, Jeff. 2017. The Road to Jonestown: Jim Jones and Peoples Temple. New York: Simon & Schuster.

“Guyana Inquest.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13675 on 1 July 2020.

Hall, John R. 1987 (reissued 2004). Gone From the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History. New Brunswick: Transaction Books.

Harpe, Dan. 2013. “My Experience with Jim Jones and Peoples Temple.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=30265 on 19 June 2020.

Jones, Marceline. n.d. “Interview with Marceline Jones.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/MarcelinesWords2.pdf on 19 May 2020.

Jones, Marceline. n.d. “Undated Recollection.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/02-marceline.pdf on 5 February 2020.

Jones, Marceline and Lynetta Jones. 1975. “A joint statement of Marceline Jones and Lynetta Jones, 1975.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and People Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=18690 on 5 February 2020.

Jones, Stephan. 2005. “Marceline/Mom.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and People Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=32388 on 25 February 2020.

Kelley, James E. 2019 “‘I Have to Be All Things to All People’: Jim Jones, Nurture Failure, and Apocalypticism.” Pp. 363–79 in New Trends in Psychobiography, edited by Claude-Hélène Mayer. New York: Springer.

Kilduff, Marshall, and Phil Tracy. 1977. “Inside Peoples Temple.” New West Magazine, 30-38.

Kohl, Laura Johnston. 2010. Jonestown Survivor: An Insider’s Look. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse.

Kohl, Laura Johnston. 2013. “Sex in the City? Make That, The Commune.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and People Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=32698 on 5 February 2020.

Lindsey, Robert. 26 November 1978. “Jim Jones: From Poverty To Power of Life and Death.” The New York Times. Accessed from https://nyti.ms/1kRZ5k5 on 5 June 2020.

Maaga, Mary McCormick. 1998. Hearing the Voices of Jonestown: Putting a Human Face on an American Tragedy. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

“Marceline Jones Request of Carolyn Layton.” 1974. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=14092 on 5 February 2020.

Moore, Rebecca. 2018a [2009]. Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Moore, Rebecca. 2018b. “Before the Tragedy at Jonestown, the People of Peoples Temple Had a Dream.” The Conversation. Accessed from https://theconversation.com/before-the-tragedy-at-jonestown-the-people-of-peoples-temple-had-a-dream-103151 on 30 June 2020.

Moore, Rebecca. 2018c. “What is Apostolic Socialism?” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=84234 on 4 August 2020.

Moore, Rebecca. 2018d. “What Were the Disciplines and Punishments in Jonestown?” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=84234 on 2 November 2019

Moore, Rebecca. 2012. “Peoples Temple.” World Religions and Spirituality Project. Accessed from https://wrldrels.org/2016/10/08/peoples-temple/ on 2 January 2020.

Moore, Rebecca. 1985. A Sympathetic History of Jonestown: The Moore Family Involvement in Peoples Temple. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press. Also available at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Sympathetic-History-of-Jonestown.pdf

“New Nursing Home.” 1960. The Indianapolis Recorder, September 17, p. 3.

Orsot, B. Alethia. 1989. “Together We Stood, Divided We Fell.” Pp. 91–114 in The Need for a Second Look at Jonestown, edited by Rebecca Moore and Fielding McGehee III. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press. Also available at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/The-Need-for-a-Second-Look-at-Jonestown.pdf

Q573. n.d. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 2 January 2020.

Q1059-2. n.d. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 13 February 2020.

Q042. 1978. “The ‘Death Tape’.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=29084 on 20 January 2020.

Q174. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 22 December 2019.

Q191. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 22 December 2019.

Q255. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 22 December 2019.

Q436. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 22 December 2019.

Q589. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 2 January 2020.

Q591. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 31 December 2019.

Q 598. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27483 on 12 April 2019.

Q600. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 6 December 2019.

Q602. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 4 December 2019.

Q635. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 4 December 2019.

Q636. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 4 July 2020.

Q637. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 12 April 2019.

Q638. 1978. Prepared by Fielding M. McGehee III, The Jonestown Institute. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28216 on June 30, 2020.

Q734. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 22 April 2020.

Q736. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 4 December 2019.

Q787. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 4 December 2019.

Q807. 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 4 December 2019.

Q162. 1976. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 16 November 2019.

Q569. 1975. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 1 December 2019.

Q587. 1975. Prepared by Fielding M. McGeHee III, The Jonestown Institute. Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27472 on 23 May 2020.

Q568. 1974. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 13 December 2019.

Q233. 1973. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 5 February 2020.

Q775. 1973. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 2 January 2020.

Q1057-3. 1973. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 12 February 2020.

Q955. 1972. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=28703 on 31 May 2019.

Q1021. 1972. Prepared by Fielding M. McGehee III, The Jonestown Institute. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27307 on 5 February 2020.

Reiterman, Tim, with John Jacobs. 1982. Raven: The Untold Story of The Rev. Jim Jones and His People. New York: E.P. Dutton.

“Serial 427.” 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=86899 on 2 July 2019.

Stephenson, Denice, ed. 2005. Dear People: Remembering Jonestown. San Francisco: California Historical Society and Heyday Books.

“The Words of Marceline Jones.” 2013. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13155 on 24 March 2020.

Thielmann, Bonnie, with Dean Merrill. 1979. The Broken God. Elgin, IL: David C. Cook Publishing Company.

Thrash, Catherine (Hyacinth), with Marian K. Towne. 1995. The Onliest One Alive: Surviving Jonestown, Guyana. Self-published manuscript.

“Tim Stoen Affidavit of February 6, 1972.” 1972. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13836 on 2 November 2019.

Tipton, Jennifer. “6143532 Marceline Mae Baldwin Jones (1927–1978).” Find A Grave. Accessed from https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/6143532/marceline-jones#source on 22 April 2020.

Turner, Wallace. 1977. “Pastor a Charlatan to Some, a Philosopher to Wife.” P. A8 in The New York Times, September 7, p. A-8. Accessed from https://www.nytimes.com/1977/09/02/archives/pastor-a-charlatan-to-some-a-philosopher-to-wife.html on 22 June 2020.

“Who Was On the Jonestown Basketball Team and Why Were They in Georgetown on November 18?” 2017. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=68416 on 30 June 30 2020.

Winfrey, Carey. 1979. “Why 900 Died in Guyana.” The New York Times, February 25. Accessed from https://www.nytimes.com/1979/02/25/archives/why-900-died-in-guyana.html on 22 June 2020.

Wooden, Kenneth. 1981. The Children of Jonestown. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Wright, Lawrence. 1993. “Orphans of Jonestown” The New Yorker, 66–89.

Young, Jeremy. 2013. “All in the Family.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=30272 on 5 April 2020.

SUPPLEMENTARY SOURCES

Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple is a comprehensive digital library of primary source literature, first-person accounts, and scholarly analyses. It provides live streaming of 900 audiotapes made by the group during its twenty-five year existence, as well as photographs taken by group members. Transcripts and summaries of approximately 600 are currently available online. Founded in 1998 at the University of North Dakota to coincide with the twentieth anniversary of the deaths in Jonestown, the website moved to San Diego State University in 1999, where it has been housed ever since at http://jonestown.sdsu.edu through the Special Collections at SDSU Library and Information Management. The site memorializes those who died in the tragedy; documents the numerous government investigations into Peoples Temple and Jonestown (including making available more than 10,000 pages from the FBI’s RYMUR investigation); and presents Peoples Temple and its members in their own words through articles, tapes, letters, photographs and other items. The site also conveys ongoing news regarding research and events relating to the group.

Publication Date:

13 September 2020