HOMESCHOOLING MOVEMENT TIMELINE

1964: John Holt published How Children Learn.

1967: John Holt published How Children Fail.

1972: “The Dangers of Early Schooling,” by Raymond and Dennis Moore, appeared in Harper’s Magazine.

1973: Rousas Rushdoony published Institutes of Biblical Law.

1977: The first issue of Growing Without Schooling was published by John Holt.

1978: In Perchemlides v. Frizzle, Massachusetts Superior Court ruled that homeschooling is legal if parents were competent, required subjects were taught, and academic progress was verified.

1978: John Holt appeared on The Phil Donahue Show to advocate for homeschooling.

1980: Raymond Moore first appeared on James Dobson’s Focus on the Family radio broadcast.

1981: Raymond and Dorothy Moore published Home Grown Kids.

1981: John Holt published Teach Your Own.

1983: The Home School Legal Defense Association (HSLDA) was founded Michael Farris and J. Michael Smith.

1985: Sixteen percent of Phi Delta Kappa survey respondents approved of homeschooling.

1994: HSLDA demonstrated their influence by mobilizing homeschoolers to protest a House of Representatives bill (HR6) they claimed could increase regulation of homeschooling.

1999: The number of U.S. homeschoolers was estimated at 850,000 by the National Center for Education Statistics.

2000: Patrick Henry College, which was promoted as “Harvard for homeschoolers” was founded in Purcellville, Virginia.

2001: In the Phi Delta Kappa survey, respondents approving of homeschooling rose to forty-one percent.

2003: The number of U.S. homeschoolers was estimated at 1,100,000 by the National Center for Education Statistics.

2007: The number of U.S. homeschoolers was estimated at 1,500,000 by the National Center for Education Statistics.

2011: The number of U.S. homeschoolers was estimated at 1,770,000 by the National Center for Education Statistics.

2013: The Coalition for Responsible Home Education (CRHE) was founded.

2016: The number of U.S. homeschoolers was estimated at 1,700,000 by the National Center for Education Statistics.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Children have been educated at home surely as long as homes and families have existed, but the modern homeschooling movement emerged in the United States amidst a cultural backdrop where institutional schooling was the overwhelming national norm. In the early 1970s, advocacy for alternative approaches to children’s education began to gain notice in the United States. Educator and activist John Holt, [Image at right] who had already published two popular critiques of conventional schooling in 1964 (How Children Learn) and 1967 (How Children Fail), rose to prominence and emerged as a standard bearer for the fledgling homeschooling movement. In 1977, Holt began publishing Growing Without Schooling, a newsletter for homeschoolers filled with practical advice and legal strategies. The next year he appeared on The Phil Donahue Show to discuss homeschooling, and his profile (and the circulation of his newsletter) exploded. While Holt’s ideology tilted far left, secular, and prioritized children’s rights, Christian families and leaders were beginning to explore homeschooling as well. Seventh Day Adventists Raymond and Dorothy Moore [Image at right] gained prominence during the 1970s with their advocacy for keeping children at home until at least age eight, and became regular guests on conservative Christian leader James Dobson’s Focus on the Family radio program beginning in 1980. As historian Milton Gaither notes, Seventh Day Adventist writings had always emphasized the family as the foremost educational milieu, a theology that meshed easily with message of conservative Christian organizations and leadership who were gaining broad cultural and political traction in the 1980s. Gaither also points to the powerful ideological influence of Rousas J. Rushdoony on the movement during these early years; many homeschool leaders and organizations, whether or not they acknowledged it, echoed Rushdoony’s assertions that the state had no authority in the upbringing or education of children (Gaither 2017:143, 149).

While Holt’s ideology tilted far left, secular, and prioritized children’s rights, Christian families and leaders were beginning to explore homeschooling as well. Seventh Day Adventists Raymond and Dorothy Moore [Image at right] gained prominence during the 1970s with their advocacy for keeping children at home until at least age eight, and became regular guests on conservative Christian leader James Dobson’s Focus on the Family radio program beginning in 1980. As historian Milton Gaither notes, Seventh Day Adventist writings had always emphasized the family as the foremost educational milieu, a theology that meshed easily with message of conservative Christian organizations and leadership who were gaining broad cultural and political traction in the 1980s. Gaither also points to the powerful ideological influence of Rousas J. Rushdoony on the movement during these early years; many homeschool leaders and organizations, whether or not they acknowledged it, echoed Rushdoony’s assertions that the state had no authority in the upbringing or education of children (Gaither 2017:143, 149).

Regardless of whether parents were inspired by Holt’s secular vision or the growing momentum in the conservative Christian community, homeschooling in the 1970s was a largely surreptitious endeavor, as most state education laws were vague concerning its legality. One of the first cases confronting this uncertainty was Perchemlides v. Frizzle (1978), when a Massachusetts district court ruled that homeschooling was legal if parents were competent, required subjects were taught, and academic progress was verified. Over the next fifteen years, courts across the United States established its legality, with a varying range of criteria and conditions, nationwide.

With that uncertainty lifted, the phenomenon of homeschooling was poised to expand. Counting the number of homeschoolers in the United States always been notoriously difficult because of the widely inconsistent (and often nonexistent) oversight of homeschooling across different states. What seems clear, however, is its explosive growth: from a few thousand homeschoolers in the early 1970s to nearly 2,000,000 by 2012 (Lines 1998; Redford, Battle, and Bielick 2017). Consistently topping the list of parental motivations (and consistently identified as their primary reason) has been “concern about the school environment—such as safety, drugs, and negative peer pressure.” Until the late-2000s, however, data from the National Household Education survey suggests that most homeschooling growth had been among conservative, who had robust organizational networks and religious fervor to support their efforts (Stevens 2001). In the 2007 survey, eightyt-three percent of homeschool parents listed “to provide religious or moral education” as one of their motivations. In 2011, the survey separated religious and moral one reasons, with the former claimed by sixty-four percent of parents. This dropped to fifty-one percent by 2016.

While conservative Christians still likely constitute the largest demographic subset of homeschoolers in the United States, the population has clearly diversified, not only in terms of secular motivations and practices, but also among other religious traditions. Minimal English-language scholarship is available about Muslim homeschooling, but it appears to resemble conservative Christian homeschooling in its strong emphasis on providing instruction that reinforces religious teachings, commitments, and character formation (English 2016; Sarwar 2013). Anecdotal media reports suggest a growing population of Jewish homeschoolers (Kresh 2018; Eller 2013; Ivry 2019) and support groups for Mormons (Latter-day Saints), Catholics, and Seventh-day Adventists are increasingly available as well.

In a similar pattern of diversification, homeschooling has also begun to expand in terms of race and ethnicity. Fifty-nine percent of homeschoolers on the 2016 National Household Education Survey identified as white—representing about a twenty-point drop over the last twenty years. Research reveals that African Americans in particular often choose homeschooling as a form of “racial protectionism” in response to concerns about unsafe or culturally oppressive school environments. Scholars have also begun to explore the intersections of race and religion as they inform homeschooling practices (Musumunu and Mazama 2014; Mazama and Lundy 2012).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The variety of philosophical orientations toward homeschooling are evidenced by the range of curricular and pedagogical approaches employed, even among religiously-motivated homeschoolers. But underlying this methodological diversity are two ideological convictions that recur in both quantitative and qualitative research on how parents understand the purpose and practice of homeschooling, particularly among those motivated by religious commitments.

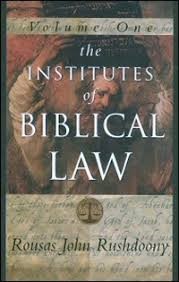

Perhaps most fundamentally, homeschool parents contend that they have primary, if not sole, responsibility for the education of their children. For religious homeschoolers, this authority is typically understood as God-ordained and therefore supersedes whatever claims the secular state might make upon the content or methods of education; the  family is viewed as a central site of resistance to contemporary secular culture. These stances are echoed in the writings of Rousas J. Rushdoony, whose Christian reconstructionism (articulated most notably in his three-volume Institutes of Biblical Law) [Image at right] holds that the American legal system should adhere to Mosaic law and that the state has no dominion over the spheres of family and church (McVicar 2015).

family is viewed as a central site of resistance to contemporary secular culture. These stances are echoed in the writings of Rousas J. Rushdoony, whose Christian reconstructionism (articulated most notably in his three-volume Institutes of Biblical Law) [Image at right] holds that the American legal system should adhere to Mosaic law and that the state has no dominion over the spheres of family and church (McVicar 2015).

This belief in the complete sovereignty of parents over their children’s education results in homeschool parents often not recognizing a distinction among childrearing, education, and formal schooling. Homeschooling is viewed as a shaping not only of intellect, but of character. All moments of daily living are seen as inherently educative, and (for many religious homeschoolers) all learning should occur within the framework of religious understanding and commitments. This conceptual merging of schooling and childrearing helps explain why many religious homeschoolers are especially resistant to state oversight of homeschooling; it is viewed as an intrusion into the private realm of parenting (Kunzman 2009).

Just as childrearing has traditionally been the responsibility of mothers, so too is the realm of homeschool instruction. This seems especially true with conservative religious adherents, whose traditionalist commitment to stay-at-home motherhood enables full focus on homeschooling, and provides encouragement to persevere amidst its demands and challenges (Lois 2013). The religious mother’s primary role in homeschooling can also provide a source of empowerment in contexts where women often lack such opportunities (McDowell 2000), and some evidence suggests that religious adherents are less likely to abandon the practice than homeschoolers more generally (Isenberg 2007).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Mothers new to homeschooling often begin by replicating the traditional classroom structure of institutional schooling, with conventional packaged curricula and fixed learning schedules. As they gain familiarity and confidence with the process, however, mothers often shift toward a more eclectic, less structured approach where learning is understood to be occurring amidst a range of daily activities and interactions (Kunzman and Gaither 2013). At the farthest end of this curricular spectrum is the practice of “unschooling,” where children choose when and what to learn, and parents serve (at most) as a facilitator of materials and learning opportunities.

Perhaps influenced by a view of human nature as inherently sinful, conservative Christians tend toward more structured curricula. Vendors abound, ranging from traditional outlets such as Bob Jones University Press and A Beka Books to smaller family publishers such as Sonl ight [Image at right] and Veritas. In recent years, a “classical curriculum” model based on the medieval trivium of grammar, logic, and rhetoric has emerged as a popular choice for Christian homeschoolers seeking rigorous academic content (Hahn 2012). With most of these curricular options, religion is not simply an additional subject or component; rather, the intellectual life only finds meaning when it aligns with religious truth. Accordingly, a religious framework animates the full range of subjects, shaping the curricular precepts and woven into examples and assignments.

ight [Image at right] and Veritas. In recent years, a “classical curriculum” model based on the medieval trivium of grammar, logic, and rhetoric has emerged as a popular choice for Christian homeschoolers seeking rigorous academic content (Hahn 2012). With most of these curricular options, religion is not simply an additional subject or component; rather, the intellectual life only finds meaning when it aligns with religious truth. Accordingly, a religious framework animates the full range of subjects, shaping the curricular precepts and woven into examples and assignments.

Until the mid-2000s, homeschooling conventions were the most efficient way for parents to explore curricular resources, and to network with like-minded families beyond their local communities. Organized and conducted by state-level Christian homeschool organizations, the largest of these events drew nearly 5,000 people to cavernous exhibit halls to peruse materials, ask questions, and derive encouragement from speakers who confirmed the wisdom of their educational choice and their capacity to exercise it successfully. In recent years, the prevalence of online vendors, materials, and support networks has significantly impacted the convention model, reducing the number of events and forcing the consolidation of others into broader regional gatherings.

Despite the wide variety of curricular philosophies and methods among homeschoolers, one common practice is group participation. Ranging from casual support gatherings in homes to formal learning cooperatives with scheduled classes taught by parents or local experts, these networks often help orient new homeschoolers to the endeavor and inculcate common values and practices (Safran 2010). Conservative religious families often reject public schools to avoid various secular influences. With this in mind, some will restrict their homeschool gatherings to like-minded families by requiring a statement of faith to participate, a form of exclusion that can generate its own tensions and disputes (Gaither 2017; Stevens 2001).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

To call homeschooling a “movement” runs the risk of exaggerating the degree  of unity and coordination involved among its adherents. The most influential organization, the Home School Legal Defense Association (HSLDA), [Image at right] claims to have over 80,000 members served by more than seventy full-time staff. While anyone homeschooling their child at least half-time can join, HSLDA describes itself as a Christian organization with only Christian employees. Founded by lawyers Michael Farris and J. Michael Smith in 1983, HSLDA began as an organization to defend homeschoolers in conflicts with school districts, particularly in the early days of the movement when the implications of vague compulsory schooling laws were being worked out in the courts. As homeschooling became more widely acknowledged as a legal option, HSLDA has maintained steady efforts to reduce regulatory requirements and combat efforts by legislators to impose additional oversight.

of unity and coordination involved among its adherents. The most influential organization, the Home School Legal Defense Association (HSLDA), [Image at right] claims to have over 80,000 members served by more than seventy full-time staff. While anyone homeschooling their child at least half-time can join, HSLDA describes itself as a Christian organization with only Christian employees. Founded by lawyers Michael Farris and J. Michael Smith in 1983, HSLDA began as an organization to defend homeschoolers in conflicts with school districts, particularly in the early days of the movement when the implications of vague compulsory schooling laws were being worked out in the courts. As homeschooling became more widely acknowledged as a legal option, HSLDA has maintained steady efforts to reduce regulatory requirements and combat efforts by legislators to impose additional oversight.

The influence of HSLDA today extends well beyond its original mission of providing legal defense for homeschool families. Patrick Henry College, which billed itself as “Harvard for homeschoolers,” shares a physical campus with HSLDA. Other offshoots of HSLDA include a political action committee that supports conservative candidates and ParentalRights.org, which advocates for legislation establishing a constitutional right to homeschool one’s children. More recently, HSLDA International has expanded the organization’s reach across the globe, as it advocates for homeschooling’s legality and the reduction of regulatory requirements.

HSLDA has its share of detractors among homeschoolers, many of whom who share its resistance to additional state regulation but would prefer a less adversarial approach to engaging with school districts, social workers, and policymakers. This clash of styles and strategy emerged perhaps most clearly in 1994, when HSLDA mobilized its members to bombard the House of Representatives switchboard with calls protesting a broader education bill that HSLDA asserted could have heightened regulation for homeschoolers. Other homeschoolers resented HSLDA’s alarmist rhetoric and aggressive response, contending that relationships with lawmakers and education officials could have been preserved with ongoing dialogue. In the wake of this episode, numerous attempts were made to establish and sustain alternative national homeschool groups, but none has ever gained sufficient traction to rival HSLDA (Gaither 2017:193). As the homeschooling community continues to diversity, it remains to be seen if HSLDA’s social conservatism on issues such as abortion and gay rights will result in a shrinking constituency.

A host of voices that are deeply critical of HSLDA and other conservative Christian organizations (e.g., Vision Forum, Bill Gothard’s Institute in Basic Life Principles, Bob Jones University, and Patrick Henry College) have emerged online during the 2010s, but these manifested more as internal disputes with limited broader impact. One group that has challenged HSLDA on the broader public stage, however, frames itself as a promoter of homeschool children’s interests (as distinct from those of their parents). The Coalition for Responsible Home Education (CRHE) (founded by homeschool alumni) maintains a database of cases of child abuse in the homeschooling context and advocates for more robust oversight, with a particular emphasis on reducing opportunities for ongoing physical and sexual abuse. CRHE has challenged HSLDA’s steadfast resistance to homeschool regulations, and appears regularly in public media coverage of homeschooling.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Perhaps the two most common outsider questions about homeschooling focus on academic achievement and socialization. Advocacy groups (most frequently HSLDA) routinely misrepresent the research record on homeschooler academic achievement, citing studies that do not draw from random samples of students and lack controls for family background. Once these variables are taken into consideration, it appears that homeschooling does not have much effect, positively or negatively, on academic achievement as compared with conventionally schooled students (Kunzman & Gaither 2013; Isenberg 2017).

A far more complex issue is that of homeschooler socialization. Outsiders often worry that children who do not attend conventional schools will be socially isolated, lacking opportunities for peer engagement and cultivation of broader cultural norms. The empirical record in this regard is mixed, and most studies suffer from significant methodological limitations. Some of this ambiguity emerges from disagreements about what constitutes desirable socialization for personal interaction; homeschool proponents often challenge the notion that institutional schooling is a necessary training ground for preparation to engage productively with broader society, and point to the benefits of a deeper immersion in family life and smaller local communities (Kunzman 2017).

Socialization for values and beliefs is an even more complicated matter, particularly when homeschooling and religion are part of the equation. Parents obviously have a desire and obligation to help shape their children’s ethical lives: how much influence should parents have in the development of their children’s identity and commitments, particularly as they progress toward adulthood? A rich scholarly literature exists about the role of education in cultivating personal autonomy in young people, including some focused specifically on the homeschooling context (Reich 2002; Blokhuis 2010; Merry and Karsten 2010). Certainly the demands of religious commitment and community can result in unreflective adherents who lack the capacity to consider alternative perspectives, but religion can also provide a secure vantage point from which to consider other visions of the good life and what can be learned from them (Kunzman 2010). Interestingly, research drawn from the National Survey of Youth and Religion confirms that parents play a pivotal role in the religious socialization of their children, but it appears that the impact of homeschooling compared to conventional schooling may be minimal (Uecker 2008).

There is also the matter of socialization for civic identity and engagement among homeschoolers, again, made especially complex when considering how one’s religious commitments should be reflected in broader society. Some critics contend that the privatized world of homeschooling risks neglecting the cultivation of shared civic bonds necessary to sustain a pluralistic democracy. Defenders respond that homeschooling (even when strongly informed by religious values and allegiances) does not reject such preparation, but rather cultivates community and connections in different ways. The empirical record is again mixed, with some research suggesting that religious homeschoolers are at least as civically involved and politically tolerant as public school students, while other studies find relatively less engagement among homeschoolers (Cheng 2014; Hill and den Dulk 2013; Kunzman 2017; Pennings et al 2011; Pennings et al 2012).

Further complicating all these debates is the reality that homeschooling takes so many different shapes in different contexts. This demographic and ideological diversity not only makes it difficult to generalize from the outside, but also generates conflicts within the movement itself. Nevertheless, the periodic efforts by legislators, media, and policymakers to increase regulatory oversight often have a temporary unifying effect among homeschooling advocates. In general, the past thirty years have seen a gradual lessening of requirements across the United States. Cases of horrific child abuse by parents who claimed to be homeschooling periodically appear in popular media and generate a groundswell of support for stronger state oversight, but these efforts almost always fail when homeschool advocacy groups mobilize in response.

Underlying these policy battles are fundamental philosophical questions about the rights and interests of parents, children, and broader society. Parents have a profound interest in raising their children and preparing them for adulthood. Children themselves have obvious, but sometimes overlooked, interests in learning to think for themselves and becoming self-sufficient. And society needs well-educated citizens who can contribute to the greater good and (in the democratic political context) govern themselves wisely. These needs and interests are regularly in tension and sometimes conflict sharply. Family and cultural identity, personal autonomy, religious commitment, and civic allegiance all place different demands on the learner, and somehow parents need to help their children navigate that journey.

As noted above, many homeschool parents do not recognize a distinction between raising their children and educating them; in this light, calls for greater state regulation of homeschooling is perceived as unjustifiable intrusion into the realm of parenting. This clash of perspectives emerges in the argument over who should bear the burden of proof that homeschooling is appropriate for any given family. If homeschooling falls into the same category as formal schooling, the state can require schools (and homeschool parents) to submit evidence that they are doing a good job. If homeschooling is categorized as simply part of the broader project of parenting, then (similar to concerns about child abuse) the burden of proof falls on the state to show that parents have forfeited their right to homeschool (Reich 2008; Glanzer 2008).

Much of this discussion has drawn from the research record and policy context of the United States, which has by far the most homeschoolers of any country. But as the practice expands internationally, sometimes in societies with a more centralized education system and different legal framework, these controversies will play out differently, often with less provision for religious communities and commitments. Over the past decade, HSLDA has devoted increasing attention to the international context, even providing legal defense for some Christian families in Sweden, Germany, and elsewhere who are prevented from homeschooling and sometimes even prosecuted for their attempts.

The freedom of homeschooling enables religiously-motivated parents to craft a learning experience that closely matches their own beliefs and commitments; such flexibility also makes it inevitable that homeschooling will continue to be a movement marked by diverse philosophies and practices, even amongst religious families. Education (whether part of formal schooling or day-to-day living) remains the locus of contention about what values, skills, and knowledge gets passed on to the next generation, and homeschooling will almost certainly continue to challenge conventional expectations and structures as part of that ongoing struggle.

IMAGES

Image #1: John Holt

Image #2: Raymond and Dorothy Moore.

Image #3: Cover of Rousas J. Rushdoony’s three-volume Institutes of Biblical Law.

Image #4: Sonlight Curriculum Ltd. logo.

Image #5: Home School Legal Defense Association logo.

REFERENCES

Blokhuis, Jason C. 2010. “Whose Custody Is It Anyway?: ‘Homeschooling’ from a Parens Patriae Perspective.” Theory and Research in Education 8:199-222.

Cheng, Albert. 2014. “Does Homeschooling or Private Schooling Promote Political Intolerance? Evidence from a Christian University.” Journal of School Choice 8:49-68.

Eller, Sandy. 2013. “Homeschooling on the Rise in Orthodox Community.” The JewishPress, July 19. Accessed from http://www.jewishpress.com/sections/family/parenting-our-children/homeschooling-on-the-rise-in-orthodox-community/2013/07/19/0/ on 3 December 2019.

English, Rebecca. 2016. “Aaishah’s Choice: Muslims Choosing Home Education for the Management of Risk.” Other Education: The Journal of Educational Alternatives 5:55-72.

Gaither, Milton. 2017. Homeschool: An American History. Second Edition. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Garvey Musumunu and Ama Mazama. 2014. “The Search for School Safety and the African American Homeschooling Experience.” Journal of Contemporary Issues in Education 9:24-38.

Glanzer, Perry L. 2008. “Rethinking the Boundaries and Burdens of Parental Authority over Education: A Response to Rob Reich’s Case Study of Homeschooling.” Educational Theory, 58: 1-16.

Hahn, Christine. 2012. “Latin in the Homeschooling Community: Results of a Large-Scale Study.” Teaching Classical Languages 4:26-51.

Isenberg, Eric J. 2007. “What Have We Learned about Homeschooling?” Peabody Journal of Education 82:387.

Ivry, Sara. 2019. “A Steep Rise in Jewish Homeschooling – Why?” Intermountain Jewish News, August 8. Accessed from https://www.ijn.com/a-steep-rise-in-jewish-homeschooling-why/ on 3 December 2019.

Kresh, Miriam. 2018. “Home Schooling, a Growing Trend in Israel.” Jerusalem Post, November 18. Accessed from https://www.jpost.com/In-Jerusalem/Education-off-the-grid-572038 on 3 December 2019.

Kunzman, Robert. 2010. “Homeschooling and Religious Fundamentalism.” International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education 3:17-28.

Kunzman, Robert. 2009. Write These Laws on Your Children: Inside the World of Conservative Christian Homeschooling. Boston: Beacon Press.

Kunzman, Robert and Milton Gaither. 2013. “Homeschooling: A Comprehensive Survey of the Research.” Other Education 2:4-59.

Lines, Patricia. 1991. “Estimating the Home Schooled Population.” No. ED337903. Washington, D.C: Office of Educational Research and Improvement.

Lois, Jennifer. 2013. Home Is Where the School Is: The Logic of Homeschooling and the Emotional Labor of Mothering. New York: New York University Press.

Mazama, A. and Lundy, G. 2012. “African American homeschooling as racial protectionism.” Journal of Black Studies 43:723-48.

McDowell, Susan A. 2000. “The Home Schooling Mother-Teacher: Toward a Theory of Social Integration.” Peabody Journal of Education 75:187-206.

McVicar, Michael J. 2015. Christian Reconstruction: R. J. Rushdoony and American Religious Conservatism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Merry, Michael S., and Sjoerd Karsten. 2010. “Restricted Liberty, Parental Choice, and Homeschooling.” Journal of Philosophy of Education 44:497-514.

Pennings, Ray, and John Seel, Deani A. Neven Van Pelt, David Sikkink, and Kathryn L. Wiens. 2011. Cardus Education Survey: Do the Motivations for Private Religious Catholic and Protestant Schooling in North America Align with Graduate Outcomes? Hamilton, Ontario: Cardus.

Pennings, Ray, and David Sikkink, Deani Van Pelt, Harro Van Brummelen, and Amy Von Heyking. 2012. Cardus Education Survey: A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats: Measuring Non-Government School Effects in Service of the Canadian Public Good. Hamilton, Ontario: Cardus.

Redford, J., Battle, D., and Bielick, S. 2017. Homeschooling in the United States: 2012 (NCES 2016-096.REV). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC.

Reich, Rob. 2008. “On Regulating Homeschooling: A Reply to Glanzer.” Educational Theory, 58:17-23.

Reich, Rob. 2002. “Testing the Boundaries of Parental Authority over Education: The Case of Homeschooling.” Pp. 275-313 in Moral and Political Education, edited by Stephen Macedo and Yael Tamir. New York: New York University Press.

Safran, Leslie. 2010. “Legitimate Peripheral Participation and Home Education.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26:107-12.

Sarwar, Sajjida. 2013. “What Motivates 21st Century Muslim Parents to Home-School Their Children?” Education Today 63:25-29.

Stevens, Mitchell L. 2001. Kingdom of Children: Culture and Controversy in the Homeschooling Movement. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Uecker, Jeremy. E. 2008. Alternative Schooling Strategies and the Religious Lives of American Adolescents. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 47:563-84.

Publication Date:

6 December 2019