SYNAGOGUE CHURCH OF ALL NATIONS (SCOAN) TIMELINE

1963 (June 12): Abdul-Fatai Temitope Balogun (later to become T. B. Joshua) was born in Arigidi, Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria, Kolawole Balogun and Folarin Balogun.

1968 (December 17): Evelyn Akabude was born in Delta State, Nigeria.

1971–1977: Known simply as Francis Balogun, Joshua attended St. Stephen Anglican Primary School, Ikare-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria. He completed one year of secondary school and then dropped out. Worked on a poultry farm after dropping out of school.

1987: Joshua claimed an inaugural vision after a forty-days and forty-nights of prayer and fasting on a “Prayer Mountain” and then going into a three-day trance which was to lead to the launching of his ministry.

1987: Joshua started “The Synagogue Church of All Nations” (SCOAN) in Lagos with eight people who formed the foundational members in a dilapidated house in Agogo-Egbe neighbourhood of Lagos.

1990: Joshua married Evelyn Akabude. The couple had three daughters: Serah, Promise, and Heart.

2006 (March 8): Joshua established Emmanuel Television under the ownership of Emmanuel Global Network in the wake of the 2004 prohibition of miracle broadcast by the National Broadcasting Commission of Nigeria (NBC).

2008: Joshua was conferred with a national honour and recognition of Order of the Federal Republic (OFR) by the Nigerian government under the administration of Alhaji Umaru Musa Yar’Adua.

2009: Joshua started a football club called My People FC as a youth empowerment outreach. Two members of Joshua’s football club (Sani Emmanuel and Ogenyi Onazi) played for the junior national football team, the Nigerian Golden Eaglets in the FIFA Under-17 world Cup.

2010 (September): SCOAN was blacklisted by the Paul Biya government in Cameroon.

2011: Joshua’s wealth was estimated by Forbes magazine to be between US$10,000,000 and US$15,000,000; he was ranked as the third-richest Nigerian Pentecostal pastor.

2014 (September 12): A hostel on T.B. Joshua’s church premises collapsed and 116 people died.

2015 (April): Joshua took delivery of a Gulfstream luxury aircraft at the cost of US $60,000,000.

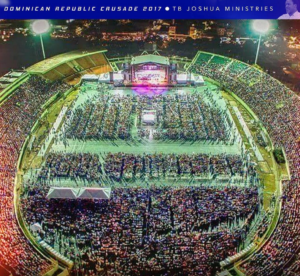

2017: Joshua was officially invited to the Dominican Republic by President Leonel Fernandez where he received a state welcome on arrival with full military honours.

2020 (February): Joshua claimed in a prophecy that the COVID-19 virus would vanish by the following March.

2020 (March): Official announcement was issued by church leaders that SCOAN would be closed for some time in line with government’s COVID-19 regulations prohibiting mass gatherings and public religious services. The closure was authorised by T. B. Joshua.

2021 (June 5): Joshua died suddenly under mysterious circumstances, supposedly after an evening service in his church.

2021 (July 9): Joshua was buried at a mausoleum inside SCOAN headquarters in Lagos.

2021 (September 9): Joshua’s wife Evelyn officially assumed leadership of SCOAN following the ruling of Justice Tijjani Ringim of Federal High Court, Lagos that ordered her reappointment as a member of the Trustees of SCOAN.

2021 (December 5): SCOAN reopened Sunday worship (after a twenty-one month hiatus) under the leadership and management of Evelyn Joshua.

2024 (January 8): The British Broadcasting Corporation under its “BBC Africa Eye” series released a three-episode documentary titled “Disciples: The Cult of T. B. Joshua.”

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Not known for the profundity of his theological thoughts or the finesse and sophistication of oratorcial skills, T. B. Joshua was the most popular, best-known and most criticised and scrutinised religious leader in Africa in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. [Image at right] He was, and to some extent still is, the most persecuted as well as the most loved Pentecostal pastor in Africa. The existence of these contradictions encapsulates the enigma that T. B. Joshua was in his lifetime, and his religious establishment still is, after his death. His crude, unorthodox and unrefined practices became for many people who flocked to his Lagos-based “The Synagogue, Church of all Nations” headquarters the drawing factors that kept them glued to his every word and public persona. The intensity and persistence of attacks and persecution of Joshua seem to equal the density, dramatic, global appeal of his charismata.

The Synagogue, Church of All Nations Church (hereafter, SCOAN) was established by Temitope Balogun Joshua, popularly called Prophet T. B. Joshua. Although the name of the organisation contains the word “church,” SCOAN is more a religiosocial and economic movement than an ecclesia in the Christian meaning of “church.” Unarguably the most popular religious personality to emerge from Africa in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, T. B. Joshua transcended the established academic characterisation of religious leaders. When alive, he embodied mystery and mysticism, miracles and miseries, controversies and contradictions, admiration and disdain. These traits were not erased but deepened even after his sudden death in June 2021. In the history of religious formations and reformations in Africa, no other religious entrepreneur had generated so much interest and intrigue, so many entanglements of diverse social spheres (politics, religious merchandising, sports, media and miracle) as T. B. Joshua.

An important key to understanding the place of T. B. Joshua in contemporary religious culture and quest lies in his biography and the myths that have emerged to account for his charismata (spiritual gifts and powers) as well as how these have influenced his self-presentation and packaging. His popularity across countries and cultures is to be understood within the social world of precarity and its multiple manifestations in late modernity and the emergent neoliberal environment of the 1980s onwards. Born on June 12, 1963, to parents Kolawole and Folarin Balogun, in Arigidi village in Ondo state in the southwest of Nigeria, Joshua was given the name Abdul-Fatai. Part of the enigma of Joshua is that the name Abdul-Fatai is an Arabic-derived Islamic name; it means servant of Allah. This has led some commentators to speculate that Joshua was born into a Muslim home and was at birth a Muslim; he was alleged to also have built a mosque. In Yorubaland, generally Muslims and Christians and indigenous religious practitioners live and share common culture including names (Peel 2016; Jansen 2021). It would therefore not be so uncommon for Christian parents to give their children non-Christian names as a sign of common heritage and belonging.

To underscore the claim that Joshua’s charismata were prenatal in origin, a legend emerged that his mother had a fifteen-month pregnancy, an unusually long term compared to the normal nine months that is standard for human gestation. While there is no way to corroborate this claim, its importance could be found in the long history of Aladura Christianity (Peel 1968; Omoyajowo 1982) in Yorubaland where important prophets or church founders are ascribed unusual births or unusual events at birth. Further, the unusual claim could be connected to the gospel narratives of Jesus’s remarkable birth and the celestial events that were said to have occurred during the time. To his many followers and members of the movement he was to found later, the myth of Joshua’s unusual birth is an act of prophecy, a mediation of divine will and intention, of who and what Joshua was to become in the unfolding of his life’s journey. Joshua’s spiritual power was preordained and encapsulated in the Yoruba concept of “àṣẹ,” mystic power (life-force) that can be inherited or harnessed from the world or cosmos and used by an individual for a variety of purposes and ends. Àṣẹ connotes the “power employed by the supreme deity to join a particular destiny to a particular self” (Hallen 2000:52). It is an enigmatic concept and affective phenomenon in Yoruba thought and culture that many resort to in explaining “creative power in the verbal and visual arts” and with “compelling aesthetic presence” and power (Abiodun 1994:71). Broadly, àṣẹ denotes that humans embody mystical and performative powers emphasising being, becoming, change and creativity impulse/s (Vega 1999). This birth narrative weaves in and out of cultural and religious beliefs that the Yoruba can easily identify with Joshua’s àṣẹ. The myth of fifteen-month gestation would indicate, would go on to develop in three creative and important directions: prophecy, healing/miracles, and generosity of spirit.

Joshua’s father died very early in his life, and so he depended almost solely on his mother and his uncle (who was a Muslim) for his upbringing. He completed his primary school education at St. Stephen’s Anglican Church from 1971 to 1977. Unsubstantiated claims have it that it was during his time at St. Stephen’s that he began showing signs of spiritual endowment as he was able to read the Christian scripture and interpret it to his fellow schoolmates. After one year of secondary school education, he dropped out of school because his mother could not support him.

The lack of formal education is often referenced as an indication that Joshua’s chrism is of divine origin; Joshua once claimed to have attended “the University of Jesus.” Unlike other Pentecostal leaders and church owners, who often point to some spiritual “father/mother-in-the-Lord” as a mentor, Joshua had no such privilege and lineage. For a person of lowly upbringing and no formal education to accomplish so much, the argument goes, must be nothing short of a miracle, a direct intervention of a powerful deity. However, before dropping out of school, Joshua mentioned that he was active in participating in activities in the Anglican Church, and on three occasions he was a chairperson of the children’s harvest-thanksgiving ceremony in the school. This claim, as usual as it seems (because children’s harvest-thanksgiving events are never chaired by children but by adults with purchasing power for the items donated) has never been corroborated nor denied by the authorities of the Anglican Church. Part of Joshua’s credentials as a Christian is the claim that he was active within the Students Christian Fellowship (SCM). Similar to the claim of being the chairperson of children’s harvest-thanksgiving event, this claim is implausible as the SCM only exists at the tertiary educational institution level and never at any secondary school in Nigeria. The search for a Christian and Pentecostal pedigree very likely accounts for these revisionist biographical claims. Josua and his handlers were eager to establish a firm Christian origin and foundation that would minimally satisfy those Christian leaders who relentlessly impugned the former and claimed he was not a Christian because he did not have a mentor and “father-in-Lord.”

After dropping out of secondary school, the youthful Temitope Joshua started earning a living for himself and supporting his mother (whom he called “wonderful mother” in a June 14, 2014 Instagram post) and other siblings. According to details posted on his Instagram handle, Joshua told his 665,000 (as of June 14, 2014) followers thus: “I was a baby before the death of my father. Consequently, I knew nothing about my late father and the entire family burden rested squarely on my mother’s shoulders.” The message was accompanied by a grey photo of his father, tagged “This is the picture of my late father, G. K. Balogun” (in all capital letters). The date of Joshua’s father’s death is not indicated in the post, and there seems to be no record of this. Similar to many events in Joshua’s life, it is difficult to specify when this event took place. Regarding how Joshua made a living as a young man, first, he would wash the mud off the feet of people who visited certain unpaved, muddy markets around his neighbourhood. He would receive a tip from benefactors for his caring act. The parallel cannot be missed with the story of Jesus washing the dirt off the feet of his disciples (John 13:3-17). When this means of earning a living was not enough, Joshua secured a menial job mucking chicken droppings on a poultry farm. In an interview he granted in 2011, Joshua said he was at this task for two years (Ukah 2016:216). For nearly a decade from about the end of the1970s until 1987, what is known of Joshua’s life is sketchy and made of the stuff of legend. For example, to demonstrate or point to his purported spirit of patriotism or belief in the Nigerian nation, it was claimed that he had the intention of joining the Nigerian military but failed to catch his train ride to the interviewing site from Lagos.

Sometime in the early 1980s, Joshua joined the Cherubim and Seraphim (C&S) Church, one of the prominent Aladura Christian movements that emerged in response to the 1918/1919 influenza epidemic in Lagos. The C&S Church movement was one of the principal actors within a broad and internally diverse Yoruba Christianity that defined the contours of southwest Nigeria from the mid-1920s through to the early 1970s when the nascent Pentecostal movement started gaining a foothold in this part of Nigeria. Many Nigerians who became pioneers of the Pentecostal movement in Nigeria were groomed within the Aladura revival of the first half of the twentieth century. The most prominent of these Pentecostal leaders and later church founders is the Reverend Josiah Akindayomi who founded the Redeemed Christian Church of God in 1942 (Ukah 2008:18-38). He was a member of the C&S from the mid-1930s until he was expelled for insubordination to church rules and regulations. Like Akindayomi before him, Joshua must have been attracted to the C&S for the group’s practical approach to Christianity and its claim and demonstration of the power of spiritual healing and prophecy, two of the most important and greatly sought-after religious goods of Aladura Christianity. In the context of social uncertainty, such as was the case in the mid-1980s when Nigeria was experiencing socioeconomic upheavals under the context of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund-induced Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP), prophecy and healing became resources in high demand. For many Africans, prophecy is both the prognostication into the future and the search for god’s voice and will for a person. Alternative and especially spiritual healing became highly sought after since social services such as medical and healthcare facilities were insufficient and poorly managed. Many individuals were unable to access these services, which made the provision of alternatives very attractive to them. Joshua was quick to learn and hone his skills under a very vibrant and competitive market for such religious goods and services as healing, prophecy and the promise of prosperity became alluring for many urban Nigerian under the “shrinkflation” of the late 1980s and early 1990s Lagos. Those who recognised the charisma of Joshua and accordingly turned into a religious and spiritual resource need to be understood not in isolation from the environment within which they lived but in connection to the religious ecology of urban Nigeria in the 1990s and thereafter.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Like many narratives of origins, the founding of The Synagogue, The Church of All Nations (SCOAN), is shrouded in stories and “mythistory.” Mythistory is the foundational and fundamental stories that a people or group believe and relate about some significant aspects of their lived experiences and lifeworld, which they found necessary to preserve for their common existence and around which they construct their sacred honour and common expectations (Mali 1991). Josua’s transformation from an inner member of Aladura Christianity to a church founder is narrated in mythistory. The foundational myth generates new myths about the person of Joshua and his spiritual endowments or charismata, which soon became the fibre and self-presentation and self-understanding of SCOAN. Like the days of “little things” (Zach 4:10), the common story of the origin of the SCOAN states that Joshua started the church with a group of eight believers in 1987 after receiving a revelation or “divine anointing” from God during an extraordinary experience. Joshua claimed to have gone to a special mountain and fasted for forty days and forty nights (as reported that Jesus did at the inauguration of his earthly ministry in Matthew 4:2). During this period he entered into a trance, a deep, sleep-like, semi-conscious state in which he was physically detached from his immediate surrounding and awareness. According to Joshua, his trance experience lasted for three days during which a superior force and power captured and subjugated his consciousness, handing him a huge Bible and a small cross. In addition, the mysterious sacred hand pointed another Bible to Joshua’s human heart, which absorbed and assimilated the Bible. Still, in trance, Joshua found himself in the midst of Peter, Paul, Moses and Elijah; Joshua recognised these biblical personalities as their names were clearly written on their chests. Reminiscent of Jesus’s baptism episode in the gospel of Luke (3:22) where a voice from heaven addressed Jesus: “you are my son; today have I fathered you” (New Jerusalem Bible translation), Joshua’s mystical encounter culminated in addressing him, thus:

I am your God; I am giving you a divine commission to go and carry out the work of the Heavenly Father … I would show you wonderful ways I would reveal myself through you, in teaching, preaching, miracles, signs and wonders for the salvation of souls” (cited in Ukah 2016:218).

This narration of a complex mystical experience, which Joshua’s followers regard as a vision and a trance, but more significantly, a call to mission, is Joshua’s apostolic legitimation. It summarises the visioner’s self-understanding and missionary expectation, that he is divinely summoned and commissioned to proclaim a unique message of salvation to the world credentialised through the performance of “miracles, signs and wonders.” Signs and wonders recall the salvific action of Yahweh to free the Israelites in the land of Egypt (Ex 7:3). Joshua’s ministry would grow and become popular on this very note or remarkable and spectacular, publicised and televised performance of miracles of healing and deliverance. While Joshua did not explain in any detail the meaning of the claimed appearance of Peter, Paul, Moses and Elijah in his personal transfiguration, it does indicate a reference to the acknowledgement of his power and a possible transfer of authority from these powerful figures of the Old (legal and prophetic authority of Moses and Elijah respectively) and New Testament (the leadership and apostolic authority of Peter and Paul respectively) to Joshua, a new Jesus for the contemporary times. His power and place in history were to save humankind from diseases and demonic possession through the production and provision of healing, material blessing, victory in the form of success, power, influence and fame, prophecy protection and prosperity. Joshua was a unique producer of religious goods many sought after in managing life’s uncertainties and vulnerabilities. His global influence through SCOAN was made manifest in those who patronised his organisation in search of these services and goods of salvation.

The name chosen by Joshua further signifies the mythistory of unifying the core authorities of the Old and New Testaments. A synagogue is not a church, and a church is not a synagogue. Early Christian group identity and institution started slowly to emerge as the followers of Jesus were refused entry into the synagogue or forcibly removed from it (ἀποσυναγώγους) by those who considered their belief in Jesus Christ as the resurrected saviour to be inconsistent with Judaism and therefore heretical (Jn 9:22; De Boer 2020). Συναγωγή (Synagoge) is the key Old Testament concept for the gathering of Israel or their representative heads. As a place of liturgical worship for the Jewish faith, it is also a place for study and assembly of the Jewish faithful. In the New Testament, however, εκκλησία (Ecclesia) was the key word denoting the congregation of God’s people, a word that was later to be translated as “church” and became, unfortunately, antagonistic to synagogue (Hort 1897). Although there was a “synagogue reform movement among the Jesus Movement in the history of early Christianity, which tried to introduce Jesus in the context of ancient traditions of Moses and Elijah, this failed because it was resisted by synagogue and Pharisee leaders (Chidester 2000:28-29). Joshua’s choice of name for his organisation and congregation of followers who believe in the authenticity of his charismata, “the Synagogue, Church” unites the history of Yahweh’s people from the beginning of salvation history in the Old Testament to its culmination in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ who is the fulfillment of the law and prophets and the promise of grace and salvation for humanity. According to anecdotal evidence from some of Joshua’s former followers (Johnson 2018:140f), the leader had the ambition and boldness to aver that the promise of grace and salvation in the power of the resurrection of Christ is only possible and accessible through his intermediary.

The evolution of a “Statement of Faith” for SCOAN was as arduous a task as it was for the transformation of Joshua from an adept in Aladura Christianity and rituals to a polished Pentecostal media superstar which he became in the early 2000s. At the time Joshua died (in 2021, SCOAN has formulated a ten-point article of faith as posted on its website SCOAN website 2022). These articles of faith appear as complicated theological statements that some commenters claim some learned followers of Joshua copied them from other churches’ website without acknowledging them. While not using the trinitarian formula, the first article concerns the relationship of the Father [who] gave His Spirit to make us like His Son, Jesus Christ […who is] the power of the Holy Spirit. As if indirectly pointing to his own rejection by mainline Pentecostal organisations in Nigeria and elsewhere, this article referenced John 14:16-17, which states how the world cannot accept Jesus who is the Spirit of Truth though this spirit convicts the world of the wrongness of sin and has the possibility of completely changing the believer’s life. “This is called being converted or born again.” The second article is about the nature, person and work of Jesus Christ, “a soul winner,” a descendant of David, and the Son of God “who reigns in power for us and still prays for us.” The third article concerns “holy men of God” who were assisted by the Holy Spirit to speak the message from God and the contemporary relevance of the Bible as the record and “message of grace and truth to us today.” Article four declares the power of God’s word to make believers the children of God when they avoid sins that bring about “eternal death and destruction.” The fifth article defines the meaning of salvation as the cleansing power and meaning of the blood of Christ to bring freedom from sin and its penalties. Article six describes the meaning of being born again as being refreshed and renewed in mind through the power of God’s word and spirit mixed with repentance and faith. Article seven, which concerns divine healing is worth quoting in full for its import in Joshua’s ministry:

Divine healing is the supernatural power of God bringing health to the human body. It is received by faith in the finished work of our Lord Jesus Christ. All the punishment Jesus Christ received before and during His crucifixion was for our healing – spirit, soul and body. By His stripes, we are healed. Divine healing was included in the benefits that Jesus Christ bought for us at Calvary.

Article eight mentions belief in and practice of water baptism, baptism in the holy spirit and speaking in tongues. Baptism in the holy spirit makes a believer a member of God’s household and a bearer of the fruits of the spirit such as “rivers of life, joy, peace and power to flow out of your spirit for the needs of others.” The celebration of the Last Supper as a central ritual of communion is the theme of article nine, which extensively reproduced Matthew 26:26-28; 2Peter1:4 and 1Corinthians 2:10; 11:26-31). The final article encapsulates the hope of an apocalyptic eschatology that of the New Testament: “Jesus Christ will come again, just as He went away (1:11; 1 Thessalonians 4:16-17).”

These articles of belief summarise the doctrinal orientation of SCOAN and point to its transformation from an Aladura Christian establishment to a popular healing and deliverance Pentecostal organisation. The complexity of these formulations and the pitch of articulation indicate that Joshua as general overseer of SCOAN and visioner and primary theologian of the group could not have possibly produced them. However, their beliefs point to increased doctrinal and theological refinement and sophistication that the drive to become a mainstream Pentecostal-charismatic church produced.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

For many reasons, T.B. Joshua’s ministry was tailor-made for television. It was a sacred drama that enthralled and entertained audiences even when it mesmerised and confounded many. As he could not speak English with the degree of eloquence other Pentecostal media personalities possessed, performances and actions on a large stage took precedence. [Image at right] Joshua’s (and consequently that of SCOAN) rise to fame came in the wake of the deregulation of the media section in Nigeria in 1992 under the military presidency of General Ibrahim B. Babangida. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Joshua had more than twenty hours of sponsored programmes each week on national, state and private television stations at the cost of several thousands of dollars (Ukah 2011:50). The television broadcast medium became, not just a medium of spreading his message and sacred drama of healing, but more importantly, an extension of his charismata, an extension of his personality, power and his church. At some point in the 1990s, Joshua held a daily religious service at this Ikotun-Lagos headquarters, each of which was recorded and edited for broadcast. Under the deregulated media economy of Nigeria and under-funded state-owned television stations, each station struggled to capture a segment of the religious media market to boast its revenue stream. Joshua, SCOAN and their endless stream of programmes became a formidable pillar and a ubiquitous presence on the airwaves.

A radical change came in March when the then-director general of the Nigerian Broadcasting Commission, Dr Silas Babajiya, announced that broadcast stations that indulged in transmitting programmes that professed indiscriminate miracles as events of daily fingertip occurrence must put a stop to it by April 30, 2004. While this announcement did not explicitly prohibit miracle broadcasts, such transmissions were required to meet certain criteria such as “provability,” “verifiability” and “believability;” in other words, there should be scientific proof of the occurrence of miracles before they are put on the air. This change in programme content and broadcast rules forced many programmes and personalities, such as Joshua, off the air; but the pause was only temporarily. Many of those Pentecostal miracle entrepreneurs with the financial means migrated their offerings to satellite television stations, mainly hosted from South Africa by Multichoice through its DSTV franchise. In addition, creating special Facebook and YouTube channels for religious offerings became viable and fanciful alternatives to explore for those who previously used national television outlets for their services. Recorded miracle healing and deliverance services on video tapes (VHS, and later compact discs) were also readily on sale in many urban bookstores, religious bookshops, roadside vendors and taxi ranks and parks all across Nigeria. Many religious organisations sold these and other religious items on their websites too. T.B. Joshua’s religious services were ubiquitous on video tapes and cassettes. He garnered international attention through these means.

With its headquarters in Lagos, Nigeria, Emmanuel TV, a satellite television station, streamed its first programmes on March 8, 2006. [Image at right] A great deal of technical and financial support for the project came from white South African followers of Joshua who thronged to SCOAN headquarters for healing and other prophetic services. With its motto stated as “Changing lives, changing nations, and changing the world” (SCOAN website 2022), Emmanuel TV is ostensibly a Christian station streaming programmes recorded at SCOAN’s Ikotun-Egbe HQ. It is hosted in Johannesburg, South Africa. It claims to be a television station with “one way and one job:” The way is Jesus, and the job is to talk about him to others through words and deeds. It does not broadcast programmes from other religious leaders as it has more than enough programming content to fill its twenty-four-hour daily schedule. The station has four mission objectives as stated on its website: i) to show the power, nature, ability, strength, life and character of God, ii) to bring to you dynamic ministers of God who not only know their faith but show their faith; iii) To create a spiritual atmosphere where God dwells in each home, and iv) To get people into Jesus and get them to stay. The station is also broadcast on MultiChoice’s DStv Channel 390 as well as on GOtv, YouTube and Facebook. Through these means and outlets, Emmanuel TV is undeniably a broadcasting station with a global reach. Emmanuel TV’s YouTube channel has 365,000 subscribers as of March 22, 2023. Even after his death on June 5, 2021, T. B. Joshua is still named and listed as “Executive Producer” of the station.

The global reach of Emmanuel TV cemented Joshua’s fame and authority as the foremost and quintessential African miracle entrepreneur of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. While the programming contents of the station vary, they all inescapably point to “the man in the Synagogue,” the title of Joshua’s first and earliest programme on Nigerian television stations in the 1990s. These programmes display instant healing, effortless production and performance of public exorcism, prescient knowledge of the future or the hidden aspects and experiences of people’s lives, and prophetic capabilities to foretell events even before they occur. Through the power of television cameras and images, specially edited, burnished, polished and choreographed, Joshua became a global religious icon of immense authority, power and wealth to define and command, even control, a large section of global Christian healing and deliverance market. Emmanuel TV demonstrates to a large global audience the attractiveness of breakthrough testimonies and narratives, the allure of success and the accessibility of divine healing and health. It turned SCOAN’s HQ into a destination for Christian tourism for those seeking healing, success, political and business power and liberation from want and stagnation. A regular Sunday service attracts between 15,000 and 20,000 worshippers and miracle-seekers. The Ikotu-Egbe HQ of SCOAN was a pilgrimage destination for many powerful political leaders and global celebrities, including sitting presidents, musicians, politicians, footballers and sportsmen and women from around the world. The list of Joshua’s high-profile visitors includes late President Umaru Yar’Adua of Nigeria, Joyce Banda (former president) of Malawi, Frederic Chiluba, former and late president of Zambia, Morgan Tsvangirai, opposition leader in Zimbabwe, Julius Malema, opposition leader in South Africa. Joshua’s political prophecy and claims to foretell election outcomes physically brought more politicians to his church than did any other religious leader in Africa. This is a key marker of difference and power between his ministry and those of other megachurch founders.

Through his life and practices, Joshua redefined divine healing and miracles as something that can be performed without the investment of training, mentorship or education but by the sheer force of personal charisma, technological mobilisation and power to create readily access at the press of a button on a remote control. The greatest export of Nigeria is religion, specifically Pentecostal-Charismatic Christianity; its biggest and most famous representative was T. B. Joshua whose formidable, almost invincible, medium was the television. However, the same tool that brought Joshua fame and fortune, generated immense controversy and disdain among some believers who cast Joshua as a magician and occult practitioner of the dark arts.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Joshua was senior prophet and the general overseer of SCOAN and all organs or units of the organisation such as Emmanual TV and Emmanuel Global Network.

The SCOAN organisation soon after its establishment became very popular once T. B. Joshua started performing on the Nigerian Television Authority (NTA) stations from the mid-1990s onwards. In the early 1990s through to about 2004 when the National Broadcasting Commission prohibited the broadcast of “miracles” on national television stations in Nigeria, Joshua, under the auspices of SCAON hosted several weekly televised programmes called “The Man in the Synagogue”. He did not patronise radio stations since this medium required great force of orature and speech  articulation. Because Joshua could barely speak meaningful English or read English texts (he spoke pidgin English interlaced with Yoruba), the programmes were densely choreographed as magical performances broadly composed of three elements. [Image at right] The first was the assembly of the sick and miracle-seekers who were arranged in rows with the type of sickness or spiritual quest they seek written boldly on large cardboards and either hung on their necks or held up prominently over their chests. This was called the “prayer line.” The second was the testimonies or purported miracles and healing received through the ministration of Joshua; and finally, the confessions of those who claimed they were experiencing misfortunes or reverse of fortune because they criticised and spoke ill of the “man of God,” that is, Joshua. Because of these testimonies and confessions, which functioned as a subtle form of public intimidation and control mechanism, many people across Africa refrained from criticising Joshua and his practices. What Joshua lacked in oratory and eloquence, he made up abundantly in performative and dramatic displays in front of television cameras. Television exposure brought in some refinement and financial resources as well. Skilled followers brought their labour and skilled expertise to bear on the production of publicity programmes as well as organisational knowledge on how to structure and maintain a degree of integrity and purpose to SCOAN. At inception, SCOAN did not have a “Statement of Faith” as doctrine or theological orientation was almost completely absent in the self-understanding and self-representation of both the founder and his organisation. SCOAN was a practical and pragmatic, problem-solving space where human vulnerabilities (sickness, possessions, failures, desires for success, quotidian problems) were addressed.

articulation. Because Joshua could barely speak meaningful English or read English texts (he spoke pidgin English interlaced with Yoruba), the programmes were densely choreographed as magical performances broadly composed of three elements. [Image at right] The first was the assembly of the sick and miracle-seekers who were arranged in rows with the type of sickness or spiritual quest they seek written boldly on large cardboards and either hung on their necks or held up prominently over their chests. This was called the “prayer line.” The second was the testimonies or purported miracles and healing received through the ministration of Joshua; and finally, the confessions of those who claimed they were experiencing misfortunes or reverse of fortune because they criticised and spoke ill of the “man of God,” that is, Joshua. Because of these testimonies and confessions, which functioned as a subtle form of public intimidation and control mechanism, many people across Africa refrained from criticising Joshua and his practices. What Joshua lacked in oratory and eloquence, he made up abundantly in performative and dramatic displays in front of television cameras. Television exposure brought in some refinement and financial resources as well. Skilled followers brought their labour and skilled expertise to bear on the production of publicity programmes as well as organisational knowledge on how to structure and maintain a degree of integrity and purpose to SCOAN. At inception, SCOAN did not have a “Statement of Faith” as doctrine or theological orientation was almost completely absent in the self-understanding and self-representation of both the founder and his organisation. SCOAN was a practical and pragmatic, problem-solving space where human vulnerabilities (sickness, possessions, failures, desires for success, quotidian problems) were addressed.

On Sunday, June 6, 2021, SCOAN released a terse, shocking and unexpected message on its official Facebook page informing its global audience (of more than 5,000,000 Facebook followers) that its general overseer and leader had died the previous day, Saturday at the age of fifty-seven years. “God has taken His Servant home – as it should be by divine will,” reads the message. Continuing, the statement said Joshua leaves behind a “legacy of service and sacrifice to God’s kingdom that is living for generations yet unborn.” It was not what any observer, believer or student of Nigerian Pentecostalism was expecting as Joshua had been constantly in the news about this failed prophecy regarding the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. He had (erroneously) prophesied that COVID-19 would be mysteriously and miraculously  brought to an abrupt end on March 27, 2020. [Image at right] As the cause of death was not announced by the SCOAN leadership, speculations ran amok as to how Joshua died and the cause of death. Minor details emerged later that Joshua finished preaching or teaching and conducting a meeting with Emmanuel TV Partners on the day he died and went into his private apartment for a brief rest and died while seated in an uncomfortable position. Aides found his body when they went to check on him after he failed to return to the “service.” The Police Commissioner of Lagos State, Hakeem Odumosu, confirmed that Joshua was officially pronounced dead at a(n) (undisclosed) hospital at about 3 am on Sunday, June 6, 2021. Although an official autopsy was widely expected, no result of such an exercise was published. Joshua’s wife, Evelyn Joshua, speaking with a delegate from the Lagos State government who came to commiserate with her, said she was not surprised at the death of her husband as it was “an act of God”; “it did not come to me as a surprise. I was not surprised when it happened. As we all know, he was in service that day” (Inyang 2021).

brought to an abrupt end on March 27, 2020. [Image at right] As the cause of death was not announced by the SCOAN leadership, speculations ran amok as to how Joshua died and the cause of death. Minor details emerged later that Joshua finished preaching or teaching and conducting a meeting with Emmanuel TV Partners on the day he died and went into his private apartment for a brief rest and died while seated in an uncomfortable position. Aides found his body when they went to check on him after he failed to return to the “service.” The Police Commissioner of Lagos State, Hakeem Odumosu, confirmed that Joshua was officially pronounced dead at a(n) (undisclosed) hospital at about 3 am on Sunday, June 6, 2021. Although an official autopsy was widely expected, no result of such an exercise was published. Joshua’s wife, Evelyn Joshua, speaking with a delegate from the Lagos State government who came to commiserate with her, said she was not surprised at the death of her husband as it was “an act of God”; “it did not come to me as a surprise. I was not surprised when it happened. As we all know, he was in service that day” (Inyang 2021).

As in life, Joshua’s death stoked many controversies as much as consternation. One major inconsistency surrounding how Joshua died is that at the time he died, religious gathering was still prohibited as a measure of containment of the COVID-19 virus in Lagos State and all-around Nigeria, making “a religious service” an unlikely activity he was engaged in just before his death. In line with the Nigerian government’s covid-19 containment measures and the prohibition of in-person church services, Joshua had unveiled a complex “Distance is not a barrier” online service where the power of technology has become a measure and medium of grace, miracles and global spectacle. While a religious service with a small number of participants and close associates was a possibility, the church never clarified what sort of service Joshua was engaged in on the Saturday evening preceding his death. Public movement was also restricted during this time making an in-person meeting with Emmanuel TV partners also improbable. Again, the church did not clarify if the meeting was in-person or remotely organised, leaving the public to speculate as to the context and manner of the popular preacher’s death.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Throughout his public career as a religious entrepreneur and leader, the singular feature of Joshua’s ministry was controversies. It seemed he thrived in it and garnered needed publicity by indulging in what many saw as outlandish claims and behaviours. The first of these controversies was the theological question surrounding the source of his power. Joshua was unrefined, unsophisticated and uneducated; he did not try to pretend he had a graduate degree in theology or bible studies from some degree mill divinity school abroad. His singular claim, when questioned about this educational and religious background, was that he went to “the University of Jesus,” and Jesus was his mentor and not any human. More than twice Joshua applied to join the Pentecostal Fellowship of Nigeria (PFN), the umbrella association of Pentecostal churches which constitutes one of five main federating bodies of the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN). Each of his applications was rejected because he was thought to be a master of dark and occult arts and powers rather than a born-again Christian leader. His dramatic healing style, peculiar teachings and practices riled many Pentecostal leaders in Nigeria (Ukah 2011:53), causing the PFN and CAN to ostracise him and anyone who fraternised with him.

A second source of controversies was the larger-than-life claims that Joshua constantly made from the pulpit at SCOAN. At the peak of the HIV-AIDS crisis in Africa in the mid-1990s, Joshua claimed he healed and could those infected with HIV or suffering from full-blown AIDS. A July 12, 1999, Newsweek edition, a Nigerian national newsmagazine published in Lagos, was devoted to Joshua’s claims about curing HIV/AIDS (for details see, Ukah 2016:222). Joshua literally challenged medical science findings that asserted there was no cure for HIV/AIDS, a position that did not sit very well with other miracle entrepreneurs as well as the medical and scientific communities. Joshua, through his numerous videos and online posts propagated by SCOAN, claimed that there is no sickness Jesus cannot heal through him, from cancer to business failures to infertility to penile enhancements (Staff Reporter 2014). In 2015, he claimed he had raised the dead. He was called a charlatan and fake Christian who peddled unbelievable and unprovable cures or claims of miracles and used his formidable media empire to extract and disseminate coerced, choreographed and stage-managed testimonies of healing.

By far the most devastating controversy in the ministerial life of Joshua started on September 12, 2014, when a hostel in his SCOAN HQ collapsed, killing 116 occupants. [Image at right] Eighty-five of the deceased were South African nationals who had come in search of cures and miracles. One hundred and thirty-one others were rescued alive with varying degrees of injuries. Rather than take responsibility for flouting state building regulations, Joshua and SCOAN claimed it was an external attack on SCOAN by the Boko Haram insurgency to assassinate its leader. Later, the church bribed journalists to change the narratives and focus on a light military CH130 Hercules aircraft. Joshua soon after called those who lost their lives in the collapsed building “martyrs of faith” who focused on life after life in keeping an appointment with God. However, as it was discovered later, those who died suffered their fate not because of their faith but because SCOAN broke building regulations, raising an originally two-storey structure into a five-storey building. In the unfolding controversies, Joshua and SCOAN did not take responsibility for their actions. Rather, they pointed accusing fingers at detractors and threatened “God’s wrath” on those spreading falsehood about the event or SCOAN or Joshua, calling these, including journalists and state investigators, “agents of Satan.” Joshua and SCOAN did all they could to impede the coroner’s investigation and report on the accident through intimidation, lawsuits, threats and physically hindering investigators from accessing the site of the accident. Even though the courts found Joshua and SCOAN culpable in the death of these miracle-seekers and religious tourists on his premises, he escaped any official punishment or indictment, showing how powerful he truly was.

T.B. Joshua was a norm-defying religious personality who embodied charismata and represented an experiment in the vicissitudes of charismatic authority. He combined in his person the Yoruba concept of “àṣẹ” (mystical and performative power), Aladura Christianity’s ritualised power of healing, and Pentecostalism’s emphasis on miracles, especially “signs and wonders.” He produced a flood of confounding wonders that baffled and intrigued many observers and made many others his disciples. He moved from the fringes and peripheries of the densely populated and intensely competitive religious market of Nigeria, transforming himself into a global religious icon and entrepreneur. He drew to himself and to the SCOAN HQ on the outskirts of Lagos very important and powerful (politically, socially, and financially) personalities. His charismata appealed and fascinated many while at the same time frightened and repelled others. He was feared and derided as much as he was loved and adored by a global followership. Similarly, he was ostracised by the local religious establishment but embraced and made welcome by foreign dignitaries and leaders of nations. He embodied charismata which he imparted by physical contact, touching and pushing and anointing. Where physical touch or contact was not possible, he commissioned millions of litres of “anointed water” (as surrogate charisma) which he shipped to several countries at great cost, while reaping a handsome profit as a religious businessman.

Charismatic authority, by its nature and character, is unstable, requiring the performance of wonders, magic and miracle to stabilise, reinscribe and (re)inforce. In the case of SCOAN and the death of Joshua, the appeal to a legal-rational power structure, such as the law courts, to stabilise and reinforce, or rather, initiate a post-charismatic structure and phase is a process of routinisation. Approaching the law courts redefines what SCOAN is for the post-charismatic phase. It also indicates that T. B. Joshua was SCOAN and SCOAN was T. B. Joshua. Following his death, his wife, Evelyn Joshua, [Image at right] succeeded him as SCOAN leader. However, the new leader of post-founder SCOAN has yet to demonstrate any charismatic endowment. Or rather, her success in appealing the interregnum state of affairs through the law courts could be understood as a demonstration of (nascent) charisma. Should she lead the organisation to higher heights or exploits, it would amount to a re-charismatisation process, which would possibly work in tandem with the process of routinisation.

The release of the BBC documentary, “Disciples: The Cult of T. B. Joshua” was a significant moment in re-evaluating the nature of inner happenings at SCOAN during the lifetime of Joshua. According to the BBC, the documentary was based on the experiences of twnety-nine former disciples in SCOAN. Disciples are those who work closely with the leadership of the SCOAN and carry out specific orders of the leader towards the proper and effective functioning of the organisation. In the documentary, claims, accusations and allegations of a very grave nature were made against T. B. Joshua. On the surface of the allegations, it was a matter of great courage to speak out against powerful and influential personalities of means, whether dead or alive. The documentary, based on interviews with former disciples of T.B. Joshua, levelled serious allegations of rape, sexual coercion, torture and forced abortions on the deceased former leader and founder of the Synagogue Church of All Nations. Specifically, eight former members of SCOAN claimed that they had experienced or witnessed sexual abuse and physical and/or psychological torture from Joshua. The documentary and the controversies it stoked were followed by a lengthy article by Madeleine Jane and Ayodeji Rotinwa of the “Open Democracy” titled “‘Abusive’ Legacy of Nigerian Megachurch Boss Lives on from Lagos to London (2024). The central claim of this article is that at least twelve or more former disciples of Joshua who are now church founder-owners “are propagating some of the Nigerian televangelist’s abusive spiritual practices even after his death.” The authors further claim that they reached their conclusion after interviewing more than two dozen former and current members of SCOAN in several countries in Africa, Europe and North America.

Within days of the release of these two documents, the SCOAN under the leadership of Joshua’s widow, Evelyn Joshua, released a statement debunking the stories. According to the Public Affairs Director of SCOAN, Mr Dare Adejumo, the characters interviewed by the BBC were disgruntled “relics of homosexual and lesbian associates.” SCOAN accused the BBC of breaching the ethics of good journalism “with [a] destructive ulterior motive for personal gains against perceived enemies.” Orock The Voice of Cameroon posted a video where he appraised the BBC documentary, thanking the organisation for its searchlight on Christian leaders and the church worldwide but also pointing out that those who made those accusations will, in turn, be investigated and scrutinised by the public. The most sustained pushback came from a former disciple for twenty-seven years and a trustee of SCOAN, Evangelist Joseph David. Posting a 19:16 minute video on YouTube, Joseph David defended his mentor and accused the former disciples who claimed to have been abused of lacking discipline and strength of character to bear the rigours of spiritual training under Joshua. Additionally, he accused the BBC of bias against Joshua and SCOAN. Debates and controversies will only get more intense as time goes on and as more light is thrown on the context/s and background of the personalities involved on and off screen in the making of the documentary as well as the inner workings of SCOAN during the lifetime of its founder and under the administrative of his widow and current leader of the mission, Evelyn Joshua.

IMAGES

Image #1: T. B. Joshua.

Image #2: A SCOAN service led by Joshua.

Image #3: Emmanuel TV logo.

Image #4: A T. B. Joshua healing.

Image #5: T. B. Joshua’s funeral.

Image #6. The SCOAN hostel collapse.

Image #7: Evelyn Joshua.

REFERENCES

Abiodun, Roland. 1994. “Understanding Yoruba art and aesthetics: The Concept of Ase.” African Arts 27:68–103.

Chidester, David. 2000. Christianity: A Global History. New York: HarperCollins.

De Boer, Martinus C. 2020. “Expulsion from the Synagogue: J.L. Martyn’s History and Theology in the Fourth Gospel Revisited.” New Testament Studies 66:367-91.

Hallen, Barry. 2000. The Good, the bad, and the Beautiful: Discourse about Values in Yoruba Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Hort, Fenton John Anthony. 1897. The Christian Ecclesia: A Course of Lecturers on the Early History and Early Conceptions of the Ecclesia, and Four Sermons. London: Macmillan.

Inyang, Ifreke. 2021. “TB Joshua’s death did not surprise me – Wife.” Daily Post, June10. Accessed from https://dailypost.ng/2021/06/10/tb-joshuas-death-did-not-surprise-me-widow/ on 25 March 2023.

Jane, Madeline and Ayodeji Rotinwa. 2024. “Abusive’ legacy of Nigerian megachurch boss lives on from Lagos to London.” Open Democracy, January 8. Accessed from https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/tb-joshua-legacy-john-chi-ark-of-god-covenant-ministry-scoan/ on 9 January 2024.

Johnson, Bisola Hephzi-Bah. 2018. The T. B. Joshua I know: Deception of the Age Unmasked. South Carolina: CreateSpace Independent Publishing.

Mali, Joseph. 1991. “Jacob Burckhardt: Myth, History and Mythistory.” History and Memory 3:86-118.

Omoyajowo, Akinyele J. 1982. Cherubim and Seraphim: The History of an African Independent Church. New York: NOK Publishers International.

Peel, J.D.Y. 2016. Christianity, Islam, and Oriṣa Religion: Three Traditions in Comparison and Interaction. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Peel, J.D.Y. 1968. Aladura: A Religious Movement among the Yoruba. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

SCOAN website. 2022. “Statement of Faith.” Synagogue Church of All Nations website. Accessed from https://www.scoan.org/about/statement-of-faith/ on 20 March 2023.

Staff Reporter. 2014. Nigeria’s “TB Joshua cures anything – from Aids to cancer. Mail & Guardian, September 17. Accessed from https://mg.co.za/article/2014-09-17-nigeria-churchs-prophet-cures-anything-from-aids-to-cancer/ on 1 April 2023.

Ukah, Asonzeh. 2016. “Prophecy, Miracle and Tragedy: The Afterlife of T. B. Joshua and the Nigerian State.” Pp. 209-32 in Religious Freedom and Religious Pluralism in Africa: Prospects and Limitations, edited by Pieter Coertzen, M. Christian Green, and Len Hansen. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Sun Press.

Ukah, Asonzeh.2011. “Banishing Miracles: Politics and Policies of Religious Broadcasting in Nigeria.” Religion and Politics 1:39-60.

Ukah, Asonzeh. 2008. A New Paradigm of Pentecostal Power: A Study of the Redeemed Christian Church of God in Nigeria. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

Vega, Marta Morena. 1999. “The Ancestral Sacred Creative Impulse of Africa an the African Diaspora: Ase, the Nexus of the Black Global Aesthetic, Lenox Avenue: A Journal of Interarts Inquiry, vol. 5: 45-57.

Publication Date:

1 April 2023

Update:

11 January 2024