FRANCES WILLARD TIMELINE

1839 (September 28): Frances Willard was born in Churchville, New York.

1857: Frances and Mary Willard enrolled at the Normal Institute.

1858–1859: Willard enrolled at Northwestern Female College.

1859 (June): Willard experienced “conversion” following a bout of typhoid.

1860 (January): Willard formally joined the Methodist Episcopal Church.

1862 (June): Willard’s sister Mary died.

1865–1866: Willard served as corresponding secretary of American Methodist Ladies Centenary Association.

1866: Willard began teaching at Genesee Wesleyan Seminary.

1868 (January): Frances’ father Josiah died.

1868–1870: Willard traveled through Europe with Kate Jackson.

1871: Willard was appointed president of newly founded Evanston College for Ladies.

1873: Evanston College for Ladies merged with Northwestern University; Willard was named dean of women at Northwestern and professor of aesthetics; she resigned in 1874.

1874: Willard joined the Woman’s Crusade, which led her to membership in the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).

1874: Willard was elected secretary of the National Congress of Women.

1874–1877: Willard served as corresponding secretary of the Chicago chapter of the WCTU and served as its president until 1877.

1876–1877: Willard served as secretary of the National WCTU.

1877: Willard joined Dwight Moody’s Gospel Institute until 1878.

1878 (March): Willard’s brother Oliver died; subsequently she became the editor of his failing newspaper, The Chicago Times, which was sold at auction later that summer.

1878: Willard was elected president of the Illinois WCTU.

1879: Willard was elected president of National WCTU, a position she held until her death in 1898.

1887: Willard was elected delegate to Methodist Episcopal Church General Conference.

1888–1890: Willard served as President of National Council of Women of the United States.

1888: Willard founded World WCTU; became its president in 1893.

1892: Frances’ mother Mary died.

1892: Willard sailed to England to meet with the British Women’s Temperance Association.

1898 (February 17): Frances Willard died of influenza; she was buried at Rosehill Cemetery in Chicago, Illinois.

BIOGRAPHY

Frances Elizabeth Caroline Willard was born on September 28, 1839 in Churchville, New York (near Rochester). She was one of three surviving children of her father, Josiah Flint Willard, a former Wisconsin Assemblyman and businessman, and mother, Mary Thompson Hill Willard, a teacher. Her childhood was somewhat itinerant as a result of her father’s changing career ambitions (from dairy farmer, to pastor, to assemblyman, to banker), a fact reflected in a number of moves, first to Oberlin, Ohio, then to Janesville, Wisconsin, and eventually settling in Evanston, Illinois.

From an early age, Willard’s parents exhibited a certain unconventional approach to gender roles, bucking notions that women must be relegated to the hearth alone. While still expecting that their daughters would attend to their household duties, Frances’ parents placed a premium on the education of all three children (Frances, Mary, and Oliver). Both girls attended Milwaukee’s Normal Institute while living in Wisconsin and then Northwestern Female College when they moved to Illinois, from which Frances graduated in 1859. Willard was particularly close to her sister, whose feminine virtues she both admired and envied. She often contrasted her own priorities, which would have been described as “masculine” at that time, with those of Mary. So when Mary died in 1862, it was a moment of both great sorrow and personal growth for Frances. Though devastated by Mary’s death, Willard found that the loss broke the tether she felt tying her to the work of the home. Mary would continue to  serve as the feminine model upon which Willard would build much of her position on temperance and, later, women’s suffrage. Willard [Image at right] was something of an enigma in the nineteenth century as a woman who sought to combine the notion of “true womanhood” or womanliness (premised on the idea that women were inherently feminine and best suited to the domestic sphere) with a demand for women’s access to public life and institutions.

serve as the feminine model upon which Willard would build much of her position on temperance and, later, women’s suffrage. Willard [Image at right] was something of an enigma in the nineteenth century as a woman who sought to combine the notion of “true womanhood” or womanliness (premised on the idea that women were inherently feminine and best suited to the domestic sphere) with a demand for women’s access to public life and institutions.

The decade of the 1860s was one of great growth for Frances, who discovered that the best way to implement her unique platform of womanliness and radical change, was through the field of education, specifically that of women. In 1866, following a stint as corresponding secretary at the American Methodist Ladies Association, Willard took a teaching position at the coeducational college named Genesee Wesleyan Seminary (though only men received actual “seminary” degrees as ministers). After embarking on a world tour from 1868–1870 with her friend Kate Jackson, she resettled in Evanston and was subsequently named president of the Methodist institution, Evanston College for Women, in 1871. When the college was subsumed into Northwestern two years later, she was named dean of all women at the university, also serving as a professor of English and art, positions she held until 1874. It was at Evanston, later Northwestern, that Willard first created a context in which young women could act “womanly” by nineteenth-century standards and yet feel free to rebel by asking questions and seeking different paths to success than were ordinarily afforded to them.

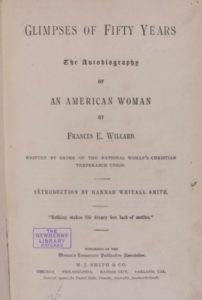

After 1874, Willard’s activism moved her into other roles beyond education, namely work as administrator and speaker in various associations and reform movements, such as temperance and women’s rights, causes to which she would devote the rest of her life and which are described in greater detail below. She also developed a career as a writer. From 1886 to 1897, she published prolifically and primarily on the ability of women. Notable among her publications are several books intended for the practical use of young women. Going against the typical manuals of nineteenth-century womanhood, her books How to Win: A Book for Girls (1886; reprinted in 1887 and 1888) and Occupations for Women (1897) focused on breaking women out of traditional gender roles and gendered occupations or spaces. Relatedly, her book Woman in the Pulpit (1888)  advocated explicitly for the ordination of women and for the admission of women into roles of church governance. Her most important book was her autobiography, Glimpses of Fifty Years, published in 1889, [Image at right] which displayed her skill as a writer and the process of how she had grown from a young woman with a great deal of potential into an activist and celebrity of international renown.

advocated explicitly for the ordination of women and for the admission of women into roles of church governance. Her most important book was her autobiography, Glimpses of Fifty Years, published in 1889, [Image at right] which displayed her skill as a writer and the process of how she had grown from a young woman with a great deal of potential into an activist and celebrity of international renown.

Willard never married, a fact that has led historians to speculate about her sexuality, though she was briefly engaged to Charles H. Fowler in 1861. (Fowler served as president of Northwestern University during her tenure there, which at least partially explains her early departure from the institution in 1874, though the primary reason was Fowler’s critique of the self-imposed “honor code” Willard had implemented among the women under her care as president and then dean). The most important relationships of her life were those she forged with other women. As was true of the nineteenth-century context, the friendship of young women was often tinged with romance (Carol Smith-Rosenberg terms it “homosocial”); whether that traversed into sexual relationships for Willard is simply speculative (Smith-Rosenberg 1975:8). What is known is that her friendships with Kate Jackson, Anna Gordon, and Lady Henry Somerset were crucial to generating Willard’s sense of the power women had to accomplish reform when they banded together.

Her friendship with Lady Henry Somerset would prove particularly fruitful. Somerset was heavily involved in women’s rights and global temperance movements, and helped to bring Willard into circles of transatlantic influence. Willard began to correspond with the British Women’s Temperance Association in the hope of creating a World Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WWCTU) beginning in 1886, eventually convening the first international convention in 1891. In 1892, she and Anna Gordon set sail for England to continue their work on women’s rights abroad.

Willard contracted influenza in the winter of 1898 as she prepared to sail for Europe. She died quietly in her sleep in her room at the Empire Hotel in New York City on February 17 of that year.

TEACHINGS/DOCTRINES

The Willard family’s early nomadism was reflected in their religious affiliation. Beginning as Baptists, the Willards joined a Congregational Church while living in Oberlin, and then, attracted as they were to the emotive and enthusiastic style of its preaching, became members of a Methodist Episcopal Church when they arrived in Wisconsin, which was the denomination in which they would remain. Frances called Methodism her denominational home throughout her life, yet her religious convictions would come to reflect her independence, ultimately leading to views that would deviate from orthodox Methodism in the final decades of the nineteenth century. From the start, she struggled with doubts as to whether she would ever be converted, even critiquing the revival model of Methodist worship. Eventually, her youthful spiritual wrangling was resolved, and in 1860 she expressed a belief that she had been converted. Her Christian conviction was so great that at one point Willard stated a desire to become an ordained minister, even serving as a principal evangelist on Dwight Moody’s staff during her stint at his Bible Institute in Chicago. Arguably, however, she channeled her desire for formal religious leadership into her social reform work, which always had a religious bent.

From an early age, Willard [Image at right] began developing a “feminist” consciousness, though she would not have termed it as such. Her denunciation of any literal reading of the Bible may have found root in her reading of biblical passages related to women. For example, she wrote in her journal in 1859 that she could not believe in the literal truth of Ephesians 5:22–24:

Wives, submit yourselves to your own husbands as you do to the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife as Christ is the head of the church, his body, of which he is the Savior. Now as the church submits to Christ, so also wives should submit to their husbands in everything.

Were she to believe that, she wrote, “I should think the evidence sufficient that God was unjust unreasonable, a tyrant” (Willard, Diary, May 26, 1859). Still, she would not take the steps of her colleague, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, whose The Woman’s Bible (1895, 1898) effectively cut, pasted, and reinterpreted passages of the Bible, with the aim of revealing the misogyny inherent in the Bible and in Christianity itself. Willard believed Stanton had gone too far. While Willard would eschew a literal interpretation of the Bible and would experience her own run-ins with the Methodist Episcopal Church hierarchy, she remained loyal to the church.

Women in the Methodist Episcopal Church were entering a period of transition just as Willard’s star began to rise. To that point, women had no formal role in Methodist governance and had not been granted access to the General Conference. However, during the 1880s the tide seemed to be turning to allow for women to hold a more formal and influential role in the church hierarchy. Reflecting this shift, in 1887, Willard was elected by her diocese (the Rock River Conference of Illinois) to serve as a representative to the 1888 meeting of the Methodist Episcopal General Conference, one of only five women to receive such a distinction. In a twist of fate, however, Willard was unable to attend due to her mother’s illness. Without Willard, the push for a greater role for women in church fizzled, as did any discussion of aligning the denomination with the cause of women’s suffrage. Though she would never formally leave the Methodist Episcopal Church, she felt disappointed at her home institution’s lack of support for women, both inside and outside of the church (Bordin 1986:167–68).

In spite of this lifelong affiliation, Willard’s religious interests were never confined to Methodism. Among other things, she dabbled in Swedenborgianism and Theosophy, expressing curiosity in the unseen world and the esoteric knowledge provided by its inhabitants. As a result of her religious eclecticism, Willard developed a unique set of theological doctrines. Combining theosophical and orthodox Christian belief, Willard held the conviction that reforming human nature was a necessary step for the spiritual and moral uplift of society as a whole. By 1889 she had come to the opinion, then increasingly common among liberal Protestants, that most world religions held the same ethical principles and that there was no exclusive path to truth and salvation. She eventually embraced her own version of Christian Socialism, which emphasized the simple precept that “God is love,” and by loving God, a Christian loved humanity, making it a moral and divine duty to seek its uplift.

It is no surprise, given the evolution of her particular brand of Christian faith, that Willard’s religious beliefs were seminal in her choice of career path, grounding her reform work in her own personal theology. Her identification as a Christian Socialist made reform work a vocational necessity (Willard 1880:95–98). More specifically, religious language found its way into the platform of temperance and women’s rights activism. For example, foundational to her advocacy for temperance was the belief that alcohol abuse was not simply a social, but a moral evil. The credo of the WCTU was that drunk men were often drunk husbands who beat their wives and children under the influence of liquor. “Spirit,” the colloquial term for hard alcohol, in this context referred quite literally to the belief that alcohol consumption imbued the drinker with evil, sinful desires. It was her ultimate adherence to the notion of Christian Socialism where she found her religious and professional niche, a platform that anticipated the Social Gospel of the early twentieth century, a movement that focused religious reform efforts on systemic social change rather than individual conversion.

LEADERSHIP

To say that Frances Willard had a commanding presence in terms of leadership is an understatement. She was at various points during the late 1880s and early 1890s the president of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), the National Council of Women of the United States (NCW), and the World Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (as well as a founder of that organization). Beginning as an educator, her functions and skills expanded to include those of fundraiser, orator, president, delegate, and politician. As her roles expanded, so did her political positions evolve, moving from a desire to educate women, to a desire to eradicate the suppression of women wrought through the vice of drinking, to the advocacy for women’s suffrage. In all of her roles and positions, she maintained the belief that women were at their best when drawing on their inherent feminine abilities and virtues, which they could  channel into industry, politics, and culture for the betterment of American society. By the 1880s, according to her biographer Ruth Bordin, she was “America’s best known woman, [Image at right] a position she would occupy until her death” (1986:112).

channel into industry, politics, and culture for the betterment of American society. By the 1880s, according to her biographer Ruth Bordin, she was “America’s best known woman, [Image at right] a position she would occupy until her death” (1986:112).

From a young age, Willard had a particular affinity for the poor and downtrodden coupled with a desire to help. This effort first took her to the field of education, but she ultimately found her stride when she joined the WCTU. Established in 1874 to combat the perils of alcoholism, the WCTU reflected the boom of reform movements spearheaded by women, as well as women’s rights reform. Its platform was based on the doctrine of “home protection,” namely that temperance concerned the protection of the family from the dangers of alcohol. And while it began with the stated aim of creating a “sober and pure world,” its efforts eventually extended to numerous nineteenth-century social problems (prostitution, sanitation, public health) all of which, in some way, were linked to the cause and progress of women. For all of these societal ills, the cure was, at base, the same. Steeped in Christianity, the WCTU was built on a platform of postmillennialism: as they eradicated societal sin, so would they spread the message of Christianity and help to usher in the Kingdom of God. Willard joined the WCTU at around the same time that she was elected to the role of secretary of the National Congress for Women in 1874, thus revealing the twin causes of her reform agenda. She was soon after elected to the role of corresponding secretary of the Chicago chapter of the WCTU.

Over time, however, Willard experienced the politicization of her views and her career. Content at first to advocate for temperance as a way to better the condition of women and society through the eradication of vice, she gradually came to the view that a true reform of society would only come if women were given greater and more practical influence in the public sphere. As a result of this evolution, in 1875 Willard began to lecture on the principles of women’s rights, temperance, and suffrage, causes that were often grouped under the phrase, “the woman question.” This led her to work under the evangelist Dwight Moody, whose oratorical skill was renowned and whose evangelical principles certainly aligned with Willard’s views at that time. She ultimately parted ways with Moody, when the more liberal Christian WCTU members grew alarmed at Moody’s influence and a seeming turn of the WCTU toward Christian evangelizing.

Beginning in the 1880s, with Willard now at the helm of the WCTU, the union moved from a platform of home protection to one of natural rights, or the idea that women had the same God-given right to vote as men. As her commitment to suffrage strengthened, she would find herself at the same conferences and conventions as Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906) and Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902). In her capacity as president of the WCTU, Willard was also dogged in her desire to unite northern and southern women around the issue of temperance, a goal that brought her on numerous speaking tours in the south (and with which she had a great deal of success). She also reached out to black women in the south, though the intersection of race and temperance would get her into trouble later (described below). In her role as WCTU president, Willard adopted the motto “Do Everything,” which essentially spoke to her belief that all areas of social progress were the work of the union, from temperance to prison reform to advocacy for the study of the social sciences.

Eventually, Willard’s visibility and experience as a speaker and organizer, led her to align the WCTU with the national Prohibition Party. By lobbying on the platform of home protection, Willard also brought to this independent political party the notion that they needed to advocate for women’s suffrage, since women would undoubtedly vote for them! The relationship was a mutually beneficial one. Seeing the opportunity to create a stronger base, Willard pushed the Prohibition Party to align with other third parties whose aims were similarly focused on social change and progress, such as the Populist Party. There were many in the WCTU and the Prohibition Party who felt that Willard’s “Do Everything” policy was diluting the specific aims of each group. Ultimately, the Prohibition Party rejected any such merger with the Populists, and the WCTU eventually balked at “too close” a relationship to any political party or with other associations, like the Knights of Labor.

In her prodigious work as a leader, Willard combined a desire for revolution with a certain conservatism based in the notion of separate spheres for women and men, a combination that made her uniquely capable, in some ways, to navigate a nineteenth-century world where these positions were often at odds.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Besides the usual struggles of any activist in pushing people toward reform, or of any administrator overstretching her capabilities, Willard experienced at least two major controversies in her life. The first involved the building of the Temple Building in Chicago, which housed the headquarters of the WCTU. The WCTU was hit hard by the financial panic of 1893. The WCTU had invested much of its capital in the construction of its headquarters and hoped that by renting out space, the building would ultimately pay for itself and replenish the WCTU’s empty coffers. However, the panic meant that the building remained mostly empty. The building, though beautiful and a symbol of the WCTU’s achievement, was turning into the union’s bane. As a result of the crisis, a faction critical of Willard gained a foothold in the WCTU and nearly ousted her as president.

Perhaps the most infamous controversy of her career was a public debate with African American civil rights leader and suffragist, Ida B. Wells (1862–1931), who accused Willard of perpetuating racist stereotypes in pursuit of her reform agenda. It was not uncommon during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries for women’s rights advocates to present other disenfranchised groups (namely blacks or immigrants) as a foil for white women in order to highlight the latter’s desirability as citizens and voters or to further their own “cures” for societal ills. The impetus for Wells’ critique was Willard’s use of the classic racist myth that white women were vulnerable to rape by black men, who she argued were particularly prone to intoxication. Wells was especially incensed at Willard’s use of the racist trope because Willard had also implied that the WCTU held an anti-lynching position. Wells questioned the hypocrisy of Willard’s rhetoric, making the point that Willard had fallen back on racist ideas in order to sustain the temperance efforts of the WCTU in the south, a fact confirmed by the fact that southern WCTU chapters were racially segregated. Following the exchange, Willard publicly denounced lynching, but still continued to employ the rhetoric of black male intoxication to argue for the dangers of alcohol.

Perhaps the most significant controversy, however, remains how to interpret the legacy of Frances Willard. Read through the failure of Prohibition (1920–1933), it is easy to relegate Willard and her work to the annals of misguided reformers and reform movements. While the Volstead Act (1919, the National Prohibition Act to implement the intent of the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution prohibiting the production and sale of alcohol for consumption) could certainly be regarded as the culmination of WCTU campaigns, success at the legislative level was only the most visible of Willard’s accomplishments. Willard’s success as organizer, writer, and speaker, her prescience in connecting Christian belief to systemic social reform, and her looming media presence as a (if not the) representative of women’s voices during the nineteenth century, point to her impact as a woman for her time and for any future efforts aimed at gender and class equality.

IMAGES

Image #1: Frances Willard learning to ride a bicycle. Courtesy of Wikimedia

Commons.

Image #2: The cover of Glimpses of Fifty Years. Courtesy of Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom, Newberry Library, Chicago.

Image #3: Portrait of Frances Willard. 1906. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Image #4: Statue of Frances Willard in the National Statuary Hall Collection, United States Capitol Building. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

REFERENCES

Bordin, Ruth. 1986. Frances Willard: A Biography. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Bordin, Ruth. 1981. Woman and Temperance: The Quest for Power and Liberty, 1873-1900. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Smith-Rosenberg, Carol. 1975. “The Female World of Love and Ritual: Relations between Nineteenth Century Women.” Signs 1:1-29.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, ed. 1895, 1898. The Woman’s Bible. 2 Volumes. Chelmsford, MA: Courier Corporation.

Willard, Frances, Helen Winslow, and Sallie White, eds. 1897. Occupations for Women. New York: Success Company.

Willard, Frances. 1889. Glimpses of Fifty Years: The Autobiography of an American Woman. Chicago: Woman’s Christian Temperance Publishing Association.

Willard, Frances. 1888. Woman in the Pulpit. Chicago: Woman’s Christian Temperance Publishing Association.

Willard, Frances. 1886; reprinted 1887, 1888. How to Win: A Book for Girls. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Willard, Frances. 1880. “Presidential Address.” Minutes of the National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. Chicago: Woman’s Christian Temperance Union.

Willard, Frances. 1857-1870. Diary of Frances Willard. Woman’s Christian Temperance Union Papers, Willard Memorial Library.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Braude, Ann. 2000. Women and American Religion. Religion in American Life Series. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cott, Nancy. 1978. The Bonds of Womanhood: “Woman’s Sphere” in New England, 1790–1835. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Earhart, Mary. 1944. Frances Willard: From Prayers to Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gifford, Carolyn De Swarte, and Amy R. Slagell, eds. 2007. Let Something Good Be Said: Speeches and Writings of Frances E. Willard. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Gordon, Anna. 1898. The Beautiful Life of Frances E. Willard: A Memorial Volume. Evanston, IL: Woman’s Temperance Publishing Association.

Hempton, David. 2008. “Sarah Grimké, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Frances Willard—Bible Stories: Evangelicalism and Feminism.” Pp. 92-113 in Evangelical Disenchantment: Nine Portraits of Faith and Doubt. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Marilley, Suzanne M. 1993. “Frances Willard and the Feminism of Fear.” Feminist Studies 19:123–46.

Slagell, Amy R. 2001. “The Rhetorical Structure of Frances E. Willard’s Campaign for Woman Suffrage, 1876-1896.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 4:1–23.

Willard, Frances. 1883. Woman and Temperance. Hartford, CT: Park Publishing Co.

Post Date:

15 June 2018