AGAINST THE STREAM BUDDHIST MEDITATION SOCIETY (ASBMS)

1971: Noah Levine was born to parents Stephen and Ondrea Levine in Los Angeles, California.

1988: Levine was incarcerated in a juvenile hall detoxification cell.

1991: Levine attended his first meditation retreat with Jack Kornfield and studied with him for ten years.

2000 (June): The Mind-Body Awareness Project was created.

2003: Levine launched a Dharma Punx group on the New York City Lower East Side.

2004: Levine’s memoir, Dharma Punx was published.

2005: Levine moved to Los Angeles.

2007: The documentary focusing on Levine’s life, “Meditate and Destroy,” was released.

2007: Levine published his second book, Against the Stream.

2008: The first Against the Stream center opened in Melrose, California.

2009: A second center opened in Santa Monica, California.

2014 (April): An outpatient facility opened in Los Angeles.

2014 (May): The sober living facility for the Refuge Recovery program opened in Hollywood.

2014 (June): Levine published Refuge Recovery.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The emergence of punk subculture in the U.S., U.K., and Australia followed on the heels of the demise of the hippie subculture in  the mid-1970s (Mageary 2012; Milenković 2007). The two subcultures shared opposition to established institutions, but punks rejected hippies for a “do whatever you want as long as no one else is hurt” philosophy and a lack of real understanding about what would be necessary for systemic change. Punk subculture has evidenced considerable class diversity but has been overwhelmingly white. The subculture has developed and been shaped differently internationally, reflecting specific cultural traditions.

the mid-1970s (Mageary 2012; Milenković 2007). The two subcultures shared opposition to established institutions, but punks rejected hippies for a “do whatever you want as long as no one else is hurt” philosophy and a lack of real understanding about what would be necessary for systemic change. Punk subculture has evidenced considerable class diversity but has been overwhelmingly white. The subculture has developed and been shaped differently internationally, reflecting specific cultural traditions.

At the center of punk subculture, of course, was punk rock, which incorporated rebellion against both conventional society and commercialized mainstream rock music. Punk musical style emphasizes relatively short, intense, fast songs containing strong anti-establishment messages. Distinctive punk rock performance characteristics have been shouting of song lyrics, DIY chorus, storming the stage, gang vocals, mosh pits and slam dancing. The punk subculture that developed around punk rock spawned numerous offshoot groups and evolved and diversified over time. However, common themes in the subculture, and particularly hardcore punk, have been an anti-authoritarian stance, non-conformity, individualism, opposition to a range of conventional values (militarism, capitalism, racism, sexism, nationalism, consumerism) and established institutions, and promotion of alternative values (animal rights, vegetarianism, environmentalism). A larger objective of the punk subculture has been replacing capitalist society with a social order built around decentralized, autonomous, egalitarian communities.

Early punk style (clothing, tattoos, piercings of various kinds, and body modification, jewelry, hairstyles) was flamboyant (tattoos, dyed hair, safety pins, metal studs/spikes, colored and spiked hair, torn clothing, display of the swastika) while later hardcore punk style was more mundane (jeans, tee shirts, working class street attire). The subculture has also been known for its explicit displays of sexual identity, such as wearing underwear as overwear. Tattooing has been a central means of symbolizing and affirming membership in the punk community. Within the context of strong individualism, there also has been an emphasis  on community within punk culture. Loose punk communities are built around punk bands, with their distinctive musical styles and political messages. In addition to rejection of conventional society, unifying values within decentralized, punk communities include a sense of being outsiders, strong individualism, egalitarianism, personal autonomy and authenticity, the DIY (Do It Yourself) ethic, and aversion to “selling out.” Members wear X or XXX tattoos (a symbol that was stamped on the hands of underage individuals entering nightclubs to forestall their purchase of alcohol) on their hands as symbols of group membership. Although the place of religion in punk subculture was a matter of some controversy, during the 1990s Christian, Krishna consciousness, Islamic (Taqwacore – “piety” core), and Buddhist (Dharma Punx) strands of punk subculture emerged (Fiscella 2012; Stewart 2011, 2012).

on community within punk culture. Loose punk communities are built around punk bands, with their distinctive musical styles and political messages. In addition to rejection of conventional society, unifying values within decentralized, punk communities include a sense of being outsiders, strong individualism, egalitarianism, personal autonomy and authenticity, the DIY (Do It Yourself) ethic, and aversion to “selling out.” Members wear X or XXX tattoos (a symbol that was stamped on the hands of underage individuals entering nightclubs to forestall their purchase of alcohol) on their hands as symbols of group membership. Although the place of religion in punk subculture was a matter of some controversy, during the 1990s Christian, Krishna consciousness, Islamic (Taqwacore – “piety” core), and Buddhist (Dharma Punx) strands of punk subculture emerged (Fiscella 2012; Stewart 2011, 2012).

Heavy drug and alcohol use was characteristic of early punk subculture. One of the groups that emerged within punk subculture in response to the heavy drug use was Straight Edge punk. Straight Edge originated in 1981 when Ian MacKaye wrote a song by that title for Minor Threat, a hardcore punk band. In the song he asserted that he was claiming “the straight edge” by rejecting drugs, alcohol, and casual sex. In addition to these three primary principles, many straight edge punks support vegetarianism, feminism. There is also a positive orientation in the culture, which involves making choices in one’s life that produce positive outcomes.

in response to the heavy drug use was Straight Edge punk. Straight Edge originated in 1981 when Ian MacKaye wrote a song by that title for Minor Threat, a hardcore punk band. In the song he asserted that he was claiming “the straight edge” by rejecting drugs, alcohol, and casual sex. In addition to these three primary principles, many straight edge punks support vegetarianism, feminism. There is also a positive orientation in the culture, which involves making choices in one’s life that produce positive outcomes.

The founder of Against the Tide Buddhist Meditation Society (ASBMS), Noah Levine, was born in 1971 to Stephen and Ondrea Levine in Los Angeles, California. His father is an American author and poet who has written extensively on Buddhist teachings, with a focus on death and dying. Levine was brought up in a Buddhist family, but he initially rejected Buddhist practice. By his own account, he had a difficult childhood. He began using marijuana and drinking alcohol at a young age and states that he was suicidal at age five. During his teenage years, he spent his time with a group of punk friends who were heavily involved in drug and alcohol use. At age sixteen he dropped out of high school and was then using both heroin and crack cocaine. Levine was arrested on a number of occasions and at age seventeen was placed in a juvenile detention facility after trying to steal a car radio to get money for drugs. Levine had already been involved with the twelve-step recovery plan of Alcoholics Anonymous. It was during his detention that he began using the Buddhist meditation techniques his father had taught him in order to rehabilitate himself. He first attended a meditation retreat in 1991 and then studied with Jack Kornfield for ten years at Spirit Rock Meditation Center in Woodacre, California. Levine also earned a Masters degree in Counseling from the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco (“Dharma Punx” n.d.).

After he had practiced mindfulness-based meditation for about five years, Levine and a close group of his friends started the Mind Body Awareness Project in 2000, which had the objective of teaching troubled youth mindfulness meditation and emotion coping strategies. In 2006, the organization was merged with a sister non-profit, and then in 2007, was merged again with Vision Youthz, an aftercare program for youth located in San Francisco. The three organizations have continued to work together in an effort to serve at-risk youth in the area. Levine currently serves on the Board of Directors (“Mind Body Awareness Project” n.d.). Levine went on to found the Against the Stream Buddhist Meditation Society in 2008 as a means of making Buddhist teachings accessible to everyone. The first center was located in Melrose, California, and about a year later the organization moved to Santa Monica. Subsequently, many chapters have been established across the U.S. Levine himself resides in Los Angeles California (“Dharma Punx” 2014).

Body Awareness Project in 2000, which had the objective of teaching troubled youth mindfulness meditation and emotion coping strategies. In 2006, the organization was merged with a sister non-profit, and then in 2007, was merged again with Vision Youthz, an aftercare program for youth located in San Francisco. The three organizations have continued to work together in an effort to serve at-risk youth in the area. Levine currently serves on the Board of Directors (“Mind Body Awareness Project” n.d.). Levine went on to found the Against the Stream Buddhist Meditation Society in 2008 as a means of making Buddhist teachings accessible to everyone. The first center was located in Melrose, California, and about a year later the organization moved to Santa Monica. Subsequently, many chapters have been established across the U.S. Levine himself resides in Los Angeles California (“Dharma Punx” 2014).

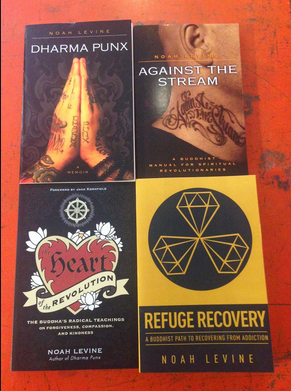

Levine began his publishing career in 2004 with his memoir, Dharma Punx, in which he traces the path toward the connection between the punk scene and Buddhist teachings. He recounts his troubled youth, addiction, and subsequent recovery. He describes his trips to monasteries in Asia and his later return to the juvenile hall where he was incarcerated, this time to teach meditation. In 2007, Levine published a second book, Against the Stream, that includes a variety of meditation techniques and instructions for both novices and skilled practitioners. He outlines a “path to freedom” The first stage, “The Rebel’s Path,” involves daily practice, an annual retreat, and following the five precepts. These practices and commitments are intensified in “The Revolutionary’s Path.” The culminating state, “The Radical’s Path,” involves an increased multi-year commitment and a willingness to teach others. His most recent book, Refuge Recovery: A Buddhist Path to Recovering from Addiction (2014), discusses the application of the Four Noble Truths and the Eight-Fold Path to the recovery program that he has created.

subsequent recovery. He describes his trips to monasteries in Asia and his later return to the juvenile hall where he was incarcerated, this time to teach meditation. In 2007, Levine published a second book, Against the Stream, that includes a variety of meditation techniques and instructions for both novices and skilled practitioners. He outlines a “path to freedom” The first stage, “The Rebel’s Path,” involves daily practice, an annual retreat, and following the five precepts. These practices and commitments are intensified in “The Revolutionary’s Path.” The culminating state, “The Radical’s Path,” involves an increased multi-year commitment and a willingness to teach others. His most recent book, Refuge Recovery: A Buddhist Path to Recovering from Addiction (2014), discusses the application of the Four Noble Truths and the Eight-Fold Path to the recovery program that he has created.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The melding of Buddhism and Punk subculture in Dharma Punx includes a brickolage of beliefs drawn from a number of religious traditions, but it is fundamentally rooted in the Vispanna Buddhist tradition, which emphasizes seeing the world as it actually is. In Against the Stream there is both a rejection of traditional Buddhism and contemporary protest subculture. Asian Buddhism is found to be corrupted through racist, sexist, classist doctrines and practices. As Against the Stream puts it, “we do not have blind faith in doctrine,” and the new tradition remains wary of the superfluous mythology and folk stories  (Preston 2009; “Against The Stream Buddhist Meditation Society” n.d.). The hippie subculture is dismissed as unrealistic; the hardcore punk subculture is deemed to be overly negative. Levine, along with Jack Kornfield, instead allies himself with emerging American Buddhism, which emphasizes relevance, accessibility, and applicability for contemporary Americans. Levine seeks a return to what he believes is the original, pure, core teachings of Buddhism contained in the Pali Sutta. For Levine, Siddhartha Gautama, who he refers to as “Sid,” was a revolutionary who taught anti-establishment rebellion and advocated a path of “Patisotagami,” that is, “against the stream” (“Against the Stream Buddhist Meditation Society” n.d.). Levine has adopted as his motto, “Meditate and Destroy” (dark thoughts).

(Preston 2009; “Against The Stream Buddhist Meditation Society” n.d.). The hippie subculture is dismissed as unrealistic; the hardcore punk subculture is deemed to be overly negative. Levine, along with Jack Kornfield, instead allies himself with emerging American Buddhism, which emphasizes relevance, accessibility, and applicability for contemporary Americans. Levine seeks a return to what he believes is the original, pure, core teachings of Buddhism contained in the Pali Sutta. For Levine, Siddhartha Gautama, who he refers to as “Sid,” was a revolutionary who taught anti-establishment rebellion and advocated a path of “Patisotagami,” that is, “against the stream” (“Against the Stream Buddhist Meditation Society” n.d.). Levine has adopted as his motto, “Meditate and Destroy” (dark thoughts).

As a Straight Edge movement, Against the Stream has three primary distinguishing tenets, abstinence from alcohol, drugs (tobacco included), and casual sex, although there are varying interpretations of what constitutes casual sex. Other values commonly found in Straight Edge groups are vegetarianism/veganism and anti-consumerism. The irrevocable commitment in claiming an edge is one made both to oneself and to the community. Given the highly individualistic nature of punk subculture, adherence to those tenets is achieved through ongoing self-monitoring and self-regulation. ASBMS centers its teachings around the Four Noble Truths: the truth of dukkha (anxiety or suffering), the truth of the origin of dukkha, the cessation of dukkha, and the truth of the path leading to the cessation of dukkha.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

ASBMS offers meditation practice as well as a variety of talks and classes on Buddhist practice with the larger goal of making Buddhist meditation as accessible as possible. Many of the classes involve Guided Meditation supplemented by a Dharma talk given by Levine or another teacher. Other classes focus on a specific type of meditation, such as relational mindfulness, which emphasizes the importance of intimacy in a community, with a new Buddhist theme incorporated each week. Another type of meditation is Recollective Awareness Meditation, where the emphasis is on remembering what was experienced during the practitioner’s meditation sitting. In addition, there alternating weeks of concentrations and insights practices as well as lovingkindness practices for the more experienced meditator.

The Refuge Recovery Program is central to ASBMS. Some of the precepts resemble the Twelve-Step Programs like Alcoholics Anonymous with which Levine initially worked. Refuge Recovery, however, operates from a Buddhist perspective. The fundamental principle of the program is that everyone has the capacity to free themselves from suffering. The four precepts that guide one’s liberation from suffering are (Levine 2014):

Addiction creates suffering. There are many forms of addiction (drugs, alcohol, sex, gambling, money, food, other people) and many forms of suffering (greed, hatred, delusion, endless craving, shame, lying, fear, hurting others or ones self, isolation, jealousy).

Addiction is not all your fault. Craving, the source of addiction, is natural Individuals therefore are not responsible for the underlying causes of addiction, but they are responsible for the behaviors that sustain addiction.

Recovery is possible. Individuals have the capacity to restore themselves to meaningful lives in which they experience well-being.

The path to recovery is the based on Buddhism’s Eight-fold Path.

According to Levine (2014:24-26), the Eightfold path of Refuge Recovery is

Understanding: We come to know that everything is ruled by cause and effect.

Intention: We renounce greed, hatred, and delusion. We train our minds to meet all pain with compassion and all pleasure with non-attached appreciation.

Communication/Community: We take refuge in the community as a place to practice wise communication and to support others on their paths. We practice being careful, honest, and wise in our communications.

Action/Engagement: We let go of the behaviors that cause harm. We ask that one renounces violence, dishonesty, sexual misconduct, and intoxication. Compassion, honesty, integrity, and service are guiding principles.

Livelihood/Service: We are of service whenever and wherever possible. And we try and ensure that our means of livelihood are such that they don’t cause harm.

Effort/Energy: We commit to daily contemplative practices like meditation and yoga, exercise, and the practices of wise actions, kindness, forgiveness, compassion which lead to self-regulatory behaviors in difficult circumstances.

Mindfulness/Meditations: We develop wisdom by means of practicing formal mindfulness meditation. We practice present-time awareness in our lives.

Concentration/Meditations: We develop the capacity to focus the mind on one thing, such as the breath, or a phrase, training the mind through the practices of lovingkindness, compassion, and forgiveness to cultivate that which we want to uncover.

Within the Refuge Recovery program, the Four Truths of Refuge Recovery serve as the guiding principles for participants, and, combined with meditation practice, help addicts apply the truths to their recovery process. M indfulness, forgiveness, and compassion are practiced through meditation and discussion at the meetings to aid participants. Consistent with the ASBMS principle of egalitarianism, meetings begin with a statement from the teacher: “My role is not authoritative. I am not an empowered Buddhist meditation teacher; I’m here to facilitate the group and lead our discussion.” The meeting sequence is a twenty to thirty-minute guided meditation, a reading, a group share period on a prearranged topic, and a final reading.. Members are reminded of the need to preserve anonymity and confidentiality. A small donation is suggested (Kremar 2014).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Noah Levine, the founding teacher of ASBMS, locates the organization relative to the 1960s hippie movement (which he criticized for being unrealistic about the sacrifices that would be necessary to produce systemic change), conventional society (which he characterizes as corrupt), traditional Buddhism (which he assesses as having been corrupted). By contrast, Against the Stream is part of the New Buddhism that rejects traditional Buddhist practice in favor of a more contemporary, accessible, and attainable practice for present-day conditions. Levine symbolizes and embodies his oppositional stance and Buddhist commitments in part through extensive tattooing, which includes a large image of Buddha on his abdomen and a Buddhist wheel of existence covering his entire back (Swick 2010).

for being unrealistic about the sacrifices that would be necessary to produce systemic change), conventional society (which he characterizes as corrupt), traditional Buddhism (which he assesses as having been corrupted). By contrast, Against the Stream is part of the New Buddhism that rejects traditional Buddhist practice in favor of a more contemporary, accessible, and attainable practice for present-day conditions. Levine symbolizes and embodies his oppositional stance and Buddhist commitments in part through extensive tattooing, which includes a large image of Buddha on his abdomen and a Buddhist wheel of existence covering his entire back (Swick 2010).

Levine works in the two centers in Los Angeles, as well as advising over twenty different groups across the U.S. A group of teachers and facilitators for meditation classes has been trained for work in the ASBMS centers. The facility offers weekly classes on American Buddhism and meditation, half-day and day-long programs, retreats, and ten month-long intensive programs in meditation. The facilitators offer a Women’s Group, and a Young People’s Group monthly (“Against the Stream Buddhist Meditation Society” n.d.). Bimonthly group classes are offered for all those who identify as people of color. There is also a bimonthly Family Program offered by Levine and the facilitators for parents and children. The services offered continue to expand as an outpatient program opened in April, 2014 in Los Angeles and a sober living program opened in May in Hollywood (Kremar 2014). Both Los Angeles centers offer weekly meetings to those interested in the Recovery Refuge program, for those recovering from addiction, led by Levine and other teachers.

Since 2008, the organization has grown to offer seventeen weekly classes and groups that included as many as 500 participants. The clientele has both grown and diversified. The teacher at the New York City group, Josh Korda, commented that “At first, the core members were just from the punk/hardcore community. Now, there are a lot of people who have never listened to hardcore or punk, never gotten tattoos or worn hoodies” (Pelly 2010). At least in New York, about one-third of attendees are “recovering addicts who are looking for nontheistic but spiritual ways to deal with their demons” (Buckley 2008).

Levine has sought to create a group of peers and eschews hierarchy in ASBMS affiliated groups. As he puts the matter: “We are all in this together seeking happiness…we are all the students. Can we take the wisdom and the compassion of the Buddha’s teachings and roots and leave behind some of the other things that I see as corruptions — the dogma, the power, the patriarchy and superstition?” (Linthicum 2009).

The teachers that work at the two centers operate under a defined Code of Ethics that dictates their relationships within their environments (“Teacher Code of Ethics n.d.). The guidelines to which all of the teachers agree are adapted from those at the Spirit Rock Meditation Center in Woodacre, California (“Against The Stream Buddhist Meditation Society” n.d.).

We undertake the precept of refraining from killing.

We undertake the precept of refraining from stealing.

We undertake the precept of refraining from false speech.

We undertake the precept of refraining from sexual misconduct.

We undertake the precept of refraining from intoxicants that cause heedlessness or loss of awareness.

ASBMS is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit and relies on donations (dana) and class fees for operating costs (Pelly 2010). While donations are suggested, no one requesting services is turned away.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

ASBMS has met little external opposition. New Buddhism has not been enthusiastically embraced by more traditional elements of the Buddhist community. And Levine, given his personal style, has both admirers and detractors (Jones 2007). As Kremar (2014) has noted with regard to his books, “I read the very polarized reviews of his first book on Amazon, which made him out to be the real deal or a fraud—there was no in-between.”

The greatest challenge that ASBMS faces is internal. The organization is expanding, both locations and services, but is constrained by its reliance on dana. As is plans new facilities, it relies on gifts to support the building projects and supplement ongoing operating costs (Pelly 2010).

REFERENCES

Buckley, Cara. 2008. A Place to Mellow Out, Without Losing Your Edge.” New York Times, December 12. Accessed from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/13/nyregion/13metjournal.html?_r=0 on 15 August 2014.

“Dana,” n.d. Against the Stream Buddhist Meditation Society. Accessed from http://www.againstthestream.org/ on 24 June 2014.

“Dharma Punx.” 2014. Accessed from http://www.dharmapunx.com/ on 15 August 2014.

Fiscella, Anthony. 2012. “From Muslim Punks to Taqwacore: An Incomplete History of Punk Islam.” Contemporary Islam 6:255–81.

Jones, Charles. 2007. “Marketing Buddhism in the United States of American: Elite Buddhism and the Formation of Religious Pluralism.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 27:214-21.

Kremar, Stephan. 2014. “The Buddhist Punk Reforming Drug Rehab.” The Daily Beast, June 16. Accessed from http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/06/16/the-buddhist-punk-reforming-drug-rehab.html on 24 June 2014.

Levine, Noah. 2014. Refuge Recovery: A Buddhist Path to Recovering from Addiction. New York: HarperOne.

Levine, Noah. 2007. Against the Stream: A Buddhist Manual for Spiritual Revolutionaries. New York: HarperOne.

Levine, Noah. 2004. Dharma Punx. New York: HarperOne.

Linthicum, Kate. 2009. “In the Stillness, Place For a Rebellious Spirit.” LA Times. Accessed from http://articles.latimes.com/2009/may/04/local/me-beliefs4 on 24 June 2014.

Mageary, Joe. 2012. “Rise Above/We’re Gonna Rise Above: A Qualitative Inquiry into the Use of Hardcore Punk Culture as Context for the Development of Preferred Identities.” Ph.D. Dissertation. San Francisco: California Institute for Integral Studies.

Milenković, Dario. 2007. “The Subcultural Group of Hardcore Punk: Sociological Research of the Group Members’ Social Origin and Their Attitudes to Nation, Religion and the Consumer Society Values.” Philosophy, Sociology and Psychology 6:67 – 80.

“Mind Body Awareness Project.” n.d. Accessed from http://www.mbaproject.org/ on 24 June 2014.

Pelly, Jenn. 2010. “A Fusion of Buddhism and Punk Rock” The Local East Village. Accessed from http://eastvillage.thelocal.nytimes.com/2010/11/15/a-fusion-of-buddhism-and-punk-rock/ on 24 June 2014.

Preston, Mark W. 2009. “The Myth of the Elephant: American Buddhist Identity and Buddho-Punk Bricolage.” Over Dinner: The Laurier M.A. Journal of Religion and Culture 1:152-69.

“Refuge Recovery- A Buddhism Based Program for Overcoming Addiction with Noah Levine” 2012. Buddhist News. Accessed from http://enews.buddhistdoor.com/en/news/d/35284 on 24 June 2014.

Smith, Bardwell. 1968. “Toward a Buddhist Anthropology: The Problem of the Secular.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 36:203-16.

Stewart, Francis. 2012. “Beyond Krishnacore: Straight Edge Punk and Implicit Religion.” Implicit Religion 15:259-88.

Stewart, Francis. 2011. Punk Rock Is My Religion: An Exploration of Straight Edge Punk as a Surrogate of Religion. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Stirling.

Swick, David. 2010. “Dharma Punx.” Shambhala Sun, May. Accessed from

http://www.shambhalasun.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=3522 on 15 August 2014.

“Teacher Code of Ethics,” n.d. Against the Stream Buddhist Meditation Society. Accessed from http://www.againstthestream.org on 24 June 2014.

Publication Date:

20 June 2014