AGE OF CONAN TIMELINE

1932: The first Conan story, “The Phoenix on the Sword” by Robert E. Howard, was published in Weird Tales magazine.

1936: Robert E. Howard committed suicide.

1950: Howard’s serialized magazine novel Hour of the Dragon from 1935-1936 was published as the book, Conan the Conqueror.

1955: Tales of Conan was published, consisting of four stories by Howard that did not originally involve Conan, which L. Sprague de Camp re-wrote, adding Conan and fantasy elements.

1957: The Return of Conan was published, a new novel written by Björn Nyberg and L. Sprague de Camp.

1967: New editions of Howard’s Conan stories began to be published, edited and with additional Conan fiction by L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter.

1970: Marvel Comics began publishing Conan comic books.

1982: The very popular movie Conan the Barbarian, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, was released.

1984: Conan the Destroyer, the sequel movie, was released.

2008: Age of Conan was launched by the Norwegian company Funcom, a massively multiplayer online role-playing game, gave thousands of players the opportunity to explore Conan’s world together.

2018: Conan Exiles was launched by the Norwegian company Funcom, a multiplayer online survival game, emphasized living in the dangerous environment after being rescued by Conan.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Although drawing upon a considerable background of ancient history and imaginative literature, the Conan Mythos was born in 1932 when Robert E. Howard published the first of his Conan stories, “The Phoenix on the Sword,” in Weird Tales magazine. Today this mythos thrives in many media, but is most directly experienced by tens of thousands of players in the massively multiplayer online game Age of Conan, and the more survival-oriented Conan Exiles. In them, the Conan Mythos is oriented to a collection of religions, either polytheistic or henotheistic depending upon the particular situation, belonging primarily to three competing fictional cultures that have affinities with actual societies of the past: Cimmerian (Celtic barbarians), Aquilonian (ancient Greece and Rome), and Stygian (ancient Egypt). The culture is more widely experienced in popular motion pictures and television series, and based on a large body of literature written by Robert E. Howard and several successor authors.

Weird Tales magazine, where Howard primarily published, was a remarkable business and subculture that also published works by H. P. Lovecraft, with whom Howard corresponded and whom he greatly admired. “The Phoenix on the Sword” began with a marvelous paragraph that established the fundamental premise of everything that followed and was repeatedly quoted over the following years by his successors:

KNOW, oh prince, that between the years when the oceans drank Atlantis and the gleaming cities, and the years of the rise of the Sons of Aryas, there was an Age undreamed of, when shining kingdoms lay spread across the world like blue mantles beneath the stars – Nemedia, Ophir, Brythunia, Hyperborea, Zamora with its dark-haired women and towers of spider-haunted mystery, Zingara with its chivalry, Koth that bordered on the pastoral lands of Shem, Stygia with its shadow-guarded tombs, Hyrkania whose riders wore steel and silk and gold. But the proudest kingdom of the world was Aquilonia, reigning supreme in the dreaming west. Hither came Conan, the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandalled feet (Howard 1932).

Howard’s suicide in 1936 might have ended the series, but some of his many fans became authors in their own right, and in 1955 L. Sprague de Camp published Tales of Conan, an exceedingly unusual posthumous collaboration with Howard, in which de Camp re-wrote four of Howard’s stories so that they became Conan focused. De Camp was not only a very successful writer of science fiction and fantasy in his own right, but also published non-fiction, and was exceedingly prolific, reportedly publishing over 100 books, including a 1983 biography of Howard. A plausible but probably controversial analysis, in the context of cultural science, is that Howard’s suicide had a function somewhat comparable to the crucifixion of Jesus, transforming him into a legendary figure and allowing other people to develop the mythos he established in wider directions. The meaning of the suicide harmonized well with the orientation of the mythos toward brutality, horror, and pessimism, rather than having the symbolism of personal sacrifice as in the case of Jesus.

In 1957, de Camp took on Björn Nyberg as co-author of The Return of Conan, an entirely new novel based on Howard’s lore but not written by him, and soon many other authors were contributing. In 1970, the very popular comic book publisher, Marvel, began issuing vast numbers of Conan comics. Exceedingly important in building the popularity of the mythos were the major motion pictures, Conan the Barbarian released in 1982, and Conan the Destroyer in 1984, both starring future California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger as Conan. These films were only very loosely based on Howard’s works, assembling fragments into two rather simple stories, often renaming characters and adding new elements. For example, Conan the Barbarian is a biography of Conan, starting when he was a small boy who watched his parents be slaughtered by raiders led by brutal sorcerer Thulsa Doom, a name borrowed from a different Howard mythos and probably representing Thoth-Amon from the Conan stories. Conan was then raised as a slave, before escaping and seeking revenge against the killer of his parents. Cimmerian that he was, Conan believed that the world was dominated by a gloomy god named Crom, while the enemy were devoted to the serpent god, Set.

Names like Conan and Set immediately raise the question of the extent to which the Conan mythos is a distillation of real ancient cultures. Cimmerians were Celtic, and “Conan” is still in use as a first name, primarily among the Irish. Set was a prominent ancient Egyptian deity, and in the Conan stories Set is a god of the Stygians who were somewhat like Egyptians. But Howard’s version of Set bears little if any resemblance to the Egyptian deity. Similarly, the chief deity of the Aquilonians during the Hyborian Era was Mitra, whose name seems like Mithras, but lacking a very clear connection to either the Persian or derivative Roman religion that worshiped Mithras in real history. Clearly, Howard was not a classical historian, and may have had only a very sketchy knowledge of the real history of ancient Europe and the Middle East, but he drew upon names, images, and other cultural material to express products of his own imagination.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

In Howard’s 1934 story, “Queen of the Black Coast,” Belit the Queen became Conan’s lover and thus was able to ask him the intimate question whether he feared the gods. He answered, “Some gods are strong to harm, others, to aid; at least so say their priests. Mitra of the Hyborians must be a strong god, because his people have builded their cities over the world. But even the Hyborians fear Set.” A rather unusual but reliable encyclopedia, The Official Handbook of the Conan Universe, was published in a Marvel Comics series, with this overview of religious culture.

The Hyborian world knew as many cults and religions as it knew tribesfolk and peoples, and religious practices and beliefs were as often the result of superstitious dread and sorcerous practices as of exalted spiritual yearnings and theological understanding. In any case, the age bred few atheists, and even the most cynical of philosophers accepted the existence of greater beings, both good and evil, as a fundamental tenet of reality. Though the various individual gods were often worshipped within strict geographical boundaries, the age was thoroughly polytheistic, and it was a matter of course for nations to acknowledge the existence of rival deities to their own. The major exception to this rule was to be found among certain priests and adherents of the god Mitra who declared their deity to be the one true god, deserving of unwavering monotheistic devotion (Anonymous 1985:16)..

In the online virtual world, Age of Conan, as in Howard’s stories, Conan had become the ruler of Aquilonia, from the city of Tarantia, which contained a temple to Mitra that existed in a degree of tension with his rule. Only under very great restrictions could a player’s avatar visit Conan’s throne room, but  the temple of Mitra was entirely open, and there were others at towns in the wider region. The exact development of the Conan mythos has not yet been fully explored by scholars, but at least by 1987 when issue 141 of the Marvel comic Savage Sword of Conan was published, the religion of Mitra was represented by a horned cross, [Image at right] rather like an Egyptian ankh. The attributes of Mitra included simplicity, dignity, and universal presence.

the temple of Mitra was entirely open, and there were others at towns in the wider region. The exact development of the Conan mythos has not yet been fully explored by scholars, but at least by 1987 when issue 141 of the Marvel comic Savage Sword of Conan was published, the religion of Mitra was represented by a horned cross, [Image at right] rather like an Egyptian ankh. The attributes of Mitra included simplicity, dignity, and universal presence.

The chief rival nation to Aquilonia, Stygia, was similar to ancient Egypt, identifying the Nile as the river Styx and adapting that name for the nation’s. Set is referenced frequently in Conan the Conqueror (The Hour of the Dragon), in terms including these:

Set the Old Serpent, men said, banished long ago from the Hyborian races, yet lurked in the shadows of the cryptic temples, and awful and mysterious were the deeds done in the nighted shrines. …serpents were sacred to Set, god of Stygia, who men said was himself a serpent. Monsters such as this were kept in the temples of Set, and when they hungered, were allowed to crawl forth into the streets to take what prey they wished. Their ghastly feasts were considered a sacrifice to the scaly god (Howard 1950).

The Cimmerians have many gods, but the most remote is also the most powerful: Crom. At one point in “Queen of the Black Coast,” Howard explained, “It was useless to call on Crom, because he was a gloomy, savage god, and he hated weaklings. But he gave a man courage at birth, and the will and might to kill his enemies, which, in the Cimmerian’s mind, was all any god should be expected to do.” In the same story, Conan himself placed this conception of Crom in a wider pessimism:

He dwells on a great mountain. [Image at right] What use to call on him? Little he cares if men live or die. Better to be silent than to call his attention to you; he will send you dooms, not fortune! He is grim and loveless, but at birth he breathes power to strive and slay into a man’s soul. What else shall men ask of the gods?… There is no hope here or hereafter in the cult of my people… In this world men struggle and suffer vainly, finding pleasure only in the bright madness of battle; dying, their souls enter a gray misty realm of clouds and icy winds, to wander cheerlessly throughout eternity… I have known many gods. He who denies them is as blind as he who trusts them too deeply… Let teachers and priests and philosophers brood over questions of reality and illusion. I know this: if life is illusion, then I am no less an illusion, and being thus, the illusion is real to me. I live, I burn with life, I love, I slay, and am content (Howard 1934)..

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The distinction between religion and magic is largely absent in the Conan mythos, and central to the practices is the channeling of supernatural powers during combat. A more complete form of religious life is found in the two multiplayer online games, Age of Conan and Conan Exiles, both produced by the innovative Norwegian company, Funcom, which invests much deeper intellectual content in its products than most of its competitors. Its 2001 science-fiction role-playing game Anarchy Online described a future in which science and technology were implicated in class conflicts, while its 2012 virtual version of our real society, Secret World, contained many occult movements. Indeed, the very popular fantasy genre of computer games is rife with simulated religions (Bainbridge 2013). Both Funcom components of the Conan mythos urged players to build their own virtual homes and explore complex natural environments, in which gods and other supernatural phenomena abounded.

Age of Conan can be played in many different ways, optionally with or without combat between the three factions, Cimmerian, Aquilonian, and Stygian, giving greater or lesser emphasis to gathering raw materials and manufacturing swords and forts, but definitely requiring far-flung exploration and the  completion of many story-related missions called quests. In addition to a few quests related to each temple and other sacred place of the factions, many involve magic connected directly or indirectly to deities. Each avatar belongs to a specific class, some of which possess magic that borders on religion. [Image at right] The Necromancer role that players may give their avatars is the best example, as explained in Age of Conan Wiki (Age of Conan Wiki n.d..):

completion of many story-related missions called quests. In addition to a few quests related to each temple and other sacred place of the factions, many involve magic connected directly or indirectly to deities. Each avatar belongs to a specific class, some of which possess magic that borders on religion. [Image at right] The Necromancer role that players may give their avatars is the best example, as explained in Age of Conan Wiki (Age of Conan Wiki n.d..):

Necromancers bring the cursed and the dead back from beyond the mortal realm to do their bidding. The true power of the Necromancer is two-fold. With mastery of necromantic magic, they animate the dead and corrupt the living. This is complemented by their ability to marshal the freezing winds of death itself and deal devastating cold damage on those who would cross their path. Thus the icy touch of death is instilled in everything the Necromancer does and they have a wide variety of spells and magic to call upon. …the Necromancer may also command the dead themselves. Animating the corpses of the fallen, the Necromancer can summon forth a series of twisted cadavers to do their bidding.

Quests in Age of Conan often involve conflict between competing religious organizations and social  movements. These conflicts are usually geographically located, such as the assassinations and other local violence between magical cults in the Stygian city of Kheshatta. One of several quest arcs begins when the player’s avatar speaks with a Priest of Set named Tuktopet, [Image at right] in this text from the game:

movements. These conflicts are usually geographically located, such as the assassinations and other local violence between magical cults in the Stygian city of Kheshatta. One of several quest arcs begins when the player’s avatar speaks with a Priest of Set named Tuktopet, [Image at right] in this text from the game:

Tuktopet: “I am Tuktopet, a Priest of Set and citizen of Kheshatta. Never forget that this is the Great Black Serpents city, though the citadels of sorcery vie for veneration.”

Player: “What can you tell me of this city?”

Tuktopet: “It is the seat of power for the mighty Thoth-Amon, may Set bless his hand.

The Black Ring Citadel stands yonder, a wicked enclave of faithless magicians who would rather raise demons and the dead than devote themselves to Lord Set.”

Player: “Tell me more of the cult of Set.”

Tuktopet: “The cult of Set has defined Stygian society and culture for millennia. It instructs our citizens and leads us in life and death. Human sacrifice is a gift of eternal servitude to the Great Serpent, and other cultures choose to misunderstand our ways.”

Player: “Do you think sorcery competes with the cult of Set?”

Tuktopet: “A number of nobles have been assassinated in recent weeks. I suspect members of the Black Ring. I need help in proving their involvement.”

While containing many quests, Conan Exiles gives greater emphasis to building both resources and skills to survive in a hostile land. Therefore, the gods play supportive roles in many practical activities, and the player has great freedom about how to collaborate with them, as the game’s Wikipedia article summarizes (“Conan Exiles” 2020):

Religion plays an important role in Conan Exiles. Players may initially swear allegiance to one of six pantheon gods, Set, Yog, Mitra, Ymir, Derketo, or Crom. All of the religions can later be learned from NPCs in-game, with the exception of Crom, as choosing this is the equivalent of choosing none at all, and is not represented by any in-game benefit. An additional deity, Jhebbal Sag, may be acquired only by speaking with a non-player character (NPC) and completing a certain dungeon. The player may then use any combination of their benefits at any given time, which mainly consists of special crafting recipes. Upon gathering enough offerings specific to each deity, their avatar may also be summoned by the player as a pinnacle form of offense, most commonly against other player bases.

Superficially, Mitra seems benevolent, Set seems sadistic, and Crom is remote, thus requiring rather different postures on the part of their worshippers. At one violent point in the 1982 movie when Conan and a companion are under attack, he exclaims:

Crom, I have never prayed to you before. I have no tongue for it. No one, not even you will remember if we were good men or bad, why we fought, or why we died. No, all that matters is that two stood against many, that’s what’s important. Valor pleases you, Crom, so grant me one request, grant me revenge! And if you do not listen, then to hell with you!

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Given that Conan is a living culture, and we focus here on religion, it can well be said that Robert E. Howard remains the leader of his virtual religion, despite having committed suicide in 1936. At the 1978 World Science Fiction Convention, a questionnaire was administered to map the dimensions of science fiction and the related forms of fantasy. Howard was the leader in the significant sword-and-sorcery area, as indicated by the fact that giving his works a high rating on a preference scale correlated 0.55 with liking sword-and-sorcery. Tied for second and third place among twenty-five authors in this genre, with a much lower correlation of 0.43, were A. Merritt who also had published in Weird Tales and was the third member of the American weird fantasy genius trinity along with Lovecraft and Howard, and British writer Michael Moorcock who was born after Howard’s death. Other attributes of fantasy fiction with which preference for Howard correlated significantly were: stories about barbarians (0.60), fantasy (0.38), action-adventure (0.36), and stories about magic (0.24). The book reporting the full results of this study described this quasi-barbarian culture in rather strong but accurate language:

The Conan stories consist of violent and horrible episodes, one bludgeoning after another, brains spilled on every battlement. Conan himself shows only the most perfunctory concern for the welfare of others. He is guided by the simple, base emotions of rage and lust; revenge is his most complex thought. The one complete novel in the series, Conan the Conqueror, begins with Conan as king of the mythical nation of Aquilonia by right of conquest. Usurpers reanimate the mummy of Xaltotun, a long-dead sorcerer, using a magic gem called the Heart of Ahriman. Weakened by black magic, Conan loses his throne, then embarks on an erratic quest to get the jewel so that friendly priests can help him regain his kingdom. Vicarious wish fulfillment is very close to the surface in these stories, and there is little, if any, attempt to justify the raw pleasure of slaughter under any civilized gloss of morality (Bainbridge 1986:134-35).

That may not seem a description of a religious creed, because we have become accustomed to think that God is good, and faith is expressed through mercy. Yet Conan strictly follows the values of Crom, the deity of his Cimmerian ethnicity. Notably, the paragraph identifies two factors that define leadership from Howard’s perspective: magic and violence. It would be easy to dismiss Conan and Crom as symptoms of a mental illness that led to Howard’s suicide only four years after the first Conan story was published, and like Lovecraft he suffered great poverty in the depths of the Great Depression, not recognized as great authors until after their deaths. Reportedly, when he was a child, Howard and his mother promised they would leave this existence together, and indeed his suicide came immediately after he learned of her death. Rather than use that fact to complete an analysis of Howard’s personality or psychopathology, here we can note that his legacy is a very different conception of the meaning of existence, than that offered by the most popular religions.

As is true today for many religion-relevant subcultures, Conan lore is communicated through many media and organizational structures, each with its own characteristics. Weird Tales, where Howard’s Conan stories were first published, existed from 1923 until 1954, when many story-focused magazines went out of business, largely in response to the success of television as a popular medium for fiction. Conan has appeared on television in both animated and live-action versions, in comic books, movies, table-top role-playing games, and computer games including the two featured here because they function as social media for large communities of Conan followers. Each revival of Conan requires a production team with its own leadership, the nature of which varies greatly.

The well-established massively multiplayer online game, Age of Conan, has a very well-developed organizational structure for the avatars of players, who not only join guilds composed of fellow players, but build their own fortified cities. These complex and massive sets of specialized buildings defended by a high wall not only concentrate social life and the production of virtual goods such as armor and weapons, but also magically increase the power and invulnerability of avatars when they are adventuring far away from the city. The founders of a guild will develop their own social structure, for command and communication, but only a few players will have the specific skills required to construct and operate the buildings of the city, thus earning honor and power aside from that defined by the status levels of guild membership. For example, the page of the official website devoted to guild cities explains the practical value of religion: “The Temple is a sanctuary for all those who have devoted themselves to the gods. In here, among hushed voices, wise priests have learned how commitment to their deity protects them in battle and grants certain invulnerability to harmful magic.” That same page explains the implications if the guild goes to war against other guilds:

Once a guild reaches a reasonable size and stature on a server, the opportunity to own a battlekeep will soon arise. But with only a limited number of battlekeeps per server allowed, guilds will have to war against each other in order to secure the power and fortune for themselves. Should you happen to come upon an available site for a battlekeep, or should you manage to bring down another guild’s battlekeep, your guild will have to start constructing its own. This involves gathering resources, erecting buildings and making sure everything is sufficiently protected. Each building within your battlekeep will grant a bonus that will affect some or all members of your guild. Buildings include the blacksmith, the temple, the alchemist workshop, the university and more. While the temple may benefit healing classes within your guild, the university might provide a bonus for all spell casting classes and your guild will need to prioritize what to build.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

The Conan mythos competes for popularity with several others that can be described as ranging from historical fantasy to sword-and-sorcery, perhaps most significantly J. R. R. Tolkien’s far less violent Lord of the Rings in which the central characters are quite ethical, and George R. R. Martin’s somewhat derivative A Song of Ice and Fire (Game of Thrones) which is between the Howard and Tolkien traditions in its degree of savagery. Other competitors are constantly entering this genre, rendering uncertain the future significance of Conan.

The social science theories that might best fit the world of Conan are not currently very popular among academics, date from early in the previous century, but have renewed applicability in today’s chaotic world. Most obviously relevant, Arnold Toynbee theorized that the birth and survival of any society depended upon the ability of the elite leadership to apply the best response to each major challenge. Earlier writers, notably Oswald Spengler and Pitirim Sorokin, believed that each civilization was ultimately doomed to fail, a perspective Howard shared. Such theories may be unpopular among academics because they are so pessimistic, yet that does not prove they are false. They certainly harmonize with the instability of leadership and total lack of human progress in the Conan culture. In his 1933 story, “Black Colossus,” Howard explained, “The gods of yesterday become the devils of tomorrow.”

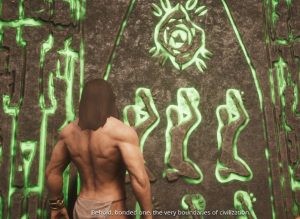

A different kind of challenge is central to the 2018 online game Conan Exiles, in which the avatar of the player must struggle to survive in the world imagined by Howard, perhaps with some help from other players, but without a civilization like Aquilonia or Stygia to depend upon. The story begins in a  wilderness where the player’s avatar has been crucified, awaiting painful death, when Conan wanders past and releases the player’s avatar, who must immediately gather sticks, stones and fibers to make crude weapons and start gathering food. Soon the staggering avatar encounters a broken lorestone on an ancient highway, [Image at right] with text intended to warn escaped slaves to return to their masters, but just one among many ruins of the lost past:

wilderness where the player’s avatar has been crucified, awaiting painful death, when Conan wanders past and releases the player’s avatar, who must immediately gather sticks, stones and fibers to make crude weapons and start gathering food. Soon the staggering avatar encounters a broken lorestone on an ancient highway, [Image at right] with text intended to warn escaped slaves to return to their masters, but just one among many ruins of the lost past:

Behold, bonded one, the very boundaries of civilization.

Beyond the passage of our highways lie the wild places of the world

where untamed savages make endless war upon each other.

You cannot pass into the endless wastes, Enslaved.

Your bonding prevents it.

Return. Follow the road. Any road.

All roads lead to the city.

While having no obvious connections to Satanism, the Conan mythos is similar in that it offers not the hope for peace and immortality, but a set of potentially sacred symbols to express the fundamental horror that surrounds human life.

IMAGES

Image #1: A colossal statue holds a cross of Mitra, at the entrance to the local temple of this Aquilonian god, in Age of Conan.

Image #2: The closed entrance to the home of Crom, in Ben Morgh mountain, just north of the Fields of the Dead, in Age of Conan.

Image #3: An Age of Conan priest in the temple of Mitra in the city of Tarantia, on the right, with a worshipper in the center and sacred statues.

Image #4: Tuktopet, Priest of Set, with a jackal statue, perhaps of Anubis, in Age of Conan.

Image #5: A beginning avatar, just released from crucifixion, ponders a broken highway lorestone in Conan Exiles.

REFERENCES

Age of Conan. “Guild Cities.” Accessed from http://www.ageofconan.com/news/guild_cities on 8 January 2020.

Age of Conan Wiki. n.d. “Necromancer.” Accessed from https://aoc.fandom.com/wiki/Necromancer on 10 January 2020.

Anonymous. 1985. The Official Handbook of the Conan Universe. New York: Marvel Comics.

Bainbridge, William Sims. 2013. eGods: Faith Versus Fantasy in Computer Gaming. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bainbridge, William Sims. 1986. Dimensions of Science Fiction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

“Conan Exiles.” 2020. Accessed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conan_Exiles on 20 January 2020.

Conan Exiles. “Broken Highway Lorestone.” Accessed from https://conanexiles.gamepedia.com/Broken_Highway_Lorestone on 8 January 2020.

De Camp, L. Sprague, Catherine Crook de Camp, and Jane Whittington Griffin. 1983. Dark Valley Destiny: The Life of Robert E. Howard. New York: Bluejay.

Howard, Robert E. 1950. Conan the Conqueror (The Hour of the Dragon). New York: Gnome. Accessed from http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks06/0600981h.html on 8 January 2020.

Howard, Robert E. 1934. “Queen of the Black Coast.” Accessed from http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks06/0600961h.html on 8 January 2020.

Howard, Robert E. 1933. “Black Colossus.” Accessed from http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks06/0600931h.html on 8 January 2020.

Howard, Robert E. 1933. “The Tower of the Elephant.” Accessed from http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks06/0600831h.html on 8 January 2020.

Howard, Robert E. 1932. “The Phoenix on the Sword.” Accessed from http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks06/0600811h.html on 8 January 2020.

Howard, Robert E., and L. Sprague de Camp. 1955. Tales of Conan. New York: Gnome.

Nyberg, Björn, and L. Sprague de Camp. 1957. The Return of Conan. New York: Gnome.

Spengler, Oswald. 1926. The Decline of the West. New York: Knopf.

Sorokin, Pitirim A. 1937. Social and Cultural Dynamics. New York: American Book Company.

Toynbee, Arnold. 1947-1957 A Study of History. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wikipedia. “Conan Exiles.” Accessed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conan_Exiles on 10 January 2020.

Publication Date:

21 January 2020