THE GHOST DANCE TIMELINE

1856 Wovoka, a Paiute Indian, was born in western Nevada.

1870 The early phase of Ghost Dance was initiated in NV by Wodziwob, a Northern Paiute Indian. The movement soon spread to other tribes and was practiced in CA and OR.

1870s The Ghost Dancers became disillusioned with the movement and the majority of movement disbanded although some offshoots such as Earth Lodge and Big Head continued to thrive.

1889 The second and more prominent phase of Ghost Dance was founded by Wovoka in NV and soon spread to other tribes.

1890 U.S. authorities became fearful of the movement’s rapid spread and officials tried to outlaw the practice.

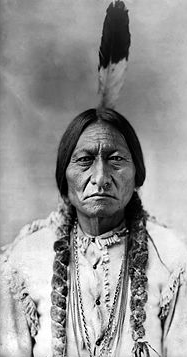

1890 (Mid-December) U.S. Army officers tried to arrest Sitting Bull, a Lakota Shaman and supporter of the Ghost Dance, resulting in a gun battle which killed Sitting Bull. US officers ordered the arrest of Big Foot, a Lakota chief.

1890 (December 28) Big Foot surrendered to U.S. military forces at Wounded Knee Creek, however in the process of disarming the Lakota armies, US Army strafed the camp with gunfire killing hundreds of Lakota.

1891 The massacre at Wounded Knee ended the widespread nature of the Ghost Dance movement although it continued in isolated places in the U.S.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The original Ghost Dance appeared on the Walker Lake Reservation in Nevada in 1870. It was initiated by Wodziwob (“Gray Hair”), a Northern Paiute Indian, as a result of visionary experiences he had in the late 1860s. Wodziwob told of having gone, in trance, to another world where he was informed that an Indian renaissance was at hand. By 1870 Indian fortunes were at a low ebb; in the wake of the Civil War the United States had concentrated on controlling Indian life and assimilating Indian people into the larger culture. Indians had been moved involuntarily from place to place; many lost their traditional lands and suffered from starvation and disease. Wodziwob’s vision predicted that tribal Indian life would soon return, that the dead would come back to life, and that animals Indians had traditionally hunted (notably the buffalo) would be restored. In order to hasten those auspicious events, Indians were instructed to perform certain round dances at night. The movement soon spread beyond the Paiute to other tribes, eventually gaining adherents in California and Oregon as well as Nevada. As the movement spread it evolved and changed; the Earth Lodge religion and the Big Head religion were among the offshoots.

After a few years the Northern Paiute Ghost Dancers became disillusioned, since Wodziwob’s prophecies did not appear to be coming true, and they gave up the dance. However, some of the other groups to which the movement had spread continued to perform it to some degree.

A new and more influential Ghost Dance movement began among the Paiute of Nevada in the late 1880s and quickly spread to many other tribes. Wovoka, a Paiute shaman also known as Jack Wilson (so named by a white family for whom he worked as a  farmhand) who had participated in the Ghost Dance of 1870, became ill with a fever late in 1888 and had visionary experiences that provided the basis for the new Ghost Dance. During an eclipse of the sun in January, 1889, he was purportedly taken to the spirit world and given instruction there. He was told that a reunion of the living and dead would soon take place, and that the deprivation suffered by Indians would end if his new teachings were followed. Wovoka told his people to treat one another justly, to avoid destructive and malicious behaviors (including fighting and drinking), and to perform the round dance that would bring about a social upheaval in which traditional Indian life would be restored. Wovoka and other members of the Paiute tribe began to perform the dance immediately, and within a few months it had spread to other tribes.

farmhand) who had participated in the Ghost Dance of 1870, became ill with a fever late in 1888 and had visionary experiences that provided the basis for the new Ghost Dance. During an eclipse of the sun in January, 1889, he was purportedly taken to the spirit world and given instruction there. He was told that a reunion of the living and dead would soon take place, and that the deprivation suffered by Indians would end if his new teachings were followed. Wovoka told his people to treat one another justly, to avoid destructive and malicious behaviors (including fighting and drinking), and to perform the round dance that would bring about a social upheaval in which traditional Indian life would be restored. Wovoka and other members of the Paiute tribe began to perform the dance immediately, and within a few months it had spread to other tribes.

Indian life was just as desperate in 1889 as it had been in 1870. All hope of defeating the United States militarily was gone, grinding poverty was endemic, and assimilation was the policy of the U. S. Government. The arrival of railroads brought waves of settlers into former Indian lands. Wovoka’s message of a new golden age was therefore received with great enthusiasm, and it spread quickly among the tribes of the Great Basin and the Great Plains. Many tribes sent delegates to visit Wovoka, hear his message, and receive instructions for the dance. Throughout the year 1890 the Ghost Dance was performed, stimulating anticipation of a return of the old ways.

The Plains Indians added a new twist to the Ghost Dance message, a belief that the great changes at hand would include the eradication of whites, or at least their being driven away from Indian lands. Some, especially the Lakota, went farther yet, creating in mid-1890 “ghost shirts” and “ghost dresses,” special garments that were believed to be bulletproof–indeed, impenetrable by any kind of weapon. The shirts were decorated with symbols of religious significance–sun, moon, stars–and often adorned with eagle feathers.

The militancy of the Lakota Ghost Dancers and the increasing popularity of the dance in the fall of 1890 made U. S. authorities nervous. The movement’s rapid spread and acquisition of followers made white settlers and the military fearful, and efforts to control the ghost dancers escalated. Officials tried to outlaw the practice, but it continued unabated. The noted shaman Sitting Bull encouraged his people to continue the dance in defiance of the ban. In mid-November an army detachment arrived at the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota to suppress the armed uprising that seemed to be looming. In mid-December army officers decided to arrest Sitting Bull, the most intransigent of the militant Indian chiefs; he was killed in a gun battle between his supporters and the soldiers. Next the U. S. authorities ordered the arrest of another Lakota chief, Big Foot; he and a band of some 350 Lakota surrendered on December 28, 1890, establishing a camp at Wounded Knee Creek. The following day a scuffle broke out between the Lakota and the U. S. military forces as the latter were in the process of disarming the former, and in panic the army detachment strafed the Indian camp with gunfire, killing hundreds of Lakota, including many trying to flee, and some dozens of army soldiers who were caught in the barrage of bullets. Most of the Lakota were wearing ghost shirts, whose defensive efficacy against bullets was rather dramatically disproved. Army troops returned to the site on New Year’s Day, 1891, and buried the victims in a mass grave.

Bull encouraged his people to continue the dance in defiance of the ban. In mid-November an army detachment arrived at the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota to suppress the armed uprising that seemed to be looming. In mid-December army officers decided to arrest Sitting Bull, the most intransigent of the militant Indian chiefs; he was killed in a gun battle between his supporters and the soldiers. Next the U. S. authorities ordered the arrest of another Lakota chief, Big Foot; he and a band of some 350 Lakota surrendered on December 28, 1890, establishing a camp at Wounded Knee Creek. The following day a scuffle broke out between the Lakota and the U. S. military forces as the latter were in the process of disarming the former, and in panic the army detachment strafed the Indian camp with gunfire, killing hundreds of Lakota, including many trying to flee, and some dozens of army soldiers who were caught in the barrage of bullets. Most of the Lakota were wearing ghost shirts, whose defensive efficacy against bullets was rather dramatically disproved. Army troops returned to the site on New Year’s Day, 1891, and buried the victims in a mass grave.

The Wounded Knee massacre put an end to the Ghost Dance as a widespread phenomenon. It was continued in several isolated places, but the expectation of the imminent return of the dead and of traditional culture was minimized. The last known Ghost Dances were held in the 1950s among the Shoshoni.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The central precept of the Ghost Dance as preached by Wovoka involved the reuniting of the living and the dead; this doctrine of resurrection of the dead may have been inspired by Christian beliefs, to which Wovoka had been exposed. The return of the dead would be accompanied by a glorious return of traditional Indian culture; in order to achieve this grand reunion, the people had to behave meritoriously. The moral code laid down by Wovoka stipulated that people were to avoid harming anyone, avoid telling lies, avoid drinking, avoid stealing, and avoid all fighting, including war. Although the change would eventually come on its own, it could be hastened by the performance of a round dance, a traditional group dance performed in a circle, at night, for several consecutive nights. The teachings surrounding the Ghost Dance were transmitted orally among believers.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

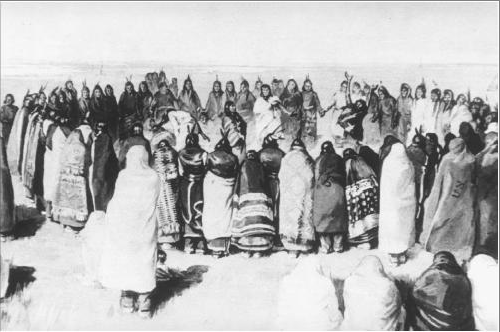

The principal ritual of the Ghost Dance religion was the dance itself. Ghost Dancers also continued to perform the rituals of their respective tribes. The Ghost Dance was a fluid religion that evolved as it spread, and several distinct movements arose as descendants of the original (1870) Ghost Dance.

In its Lakota version, the Ghost Dance circle usually had at its center a tree decorated with feathers and other symbolic ornaments that constituted offerings to the divine powers. After opening invocations, prayers, and exhortations, the dancers joined hands and began a frenetic circle dance. Many who were sick participated in the hope of being cured, and many fell down, sometimes unconscious, sometimes in trance, as the dance progressed. Eventually the dancing stopped and the participants sat in a circle, relating their experiences and visions. Later the dance might be repeated.

that constituted offerings to the divine powers. After opening invocations, prayers, and exhortations, the dancers joined hands and began a frenetic circle dance. Many who were sick participated in the hope of being cured, and many fell down, sometimes unconscious, sometimes in trance, as the dance progressed. Eventually the dancing stopped and the participants sat in a circle, relating their experiences and visions. Later the dance might be repeated.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Not a membership organization; participants numbered many thousands.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

The Ghost Dance instilled a great deal of fear in white settlers in areas where it was performed, especially by the Lakota, whose strain of the religion was especially militant. It also portended an Indian uprising and as such was suppressed by the U. S. government. That suppression led directly to the disastrous Wounded Knee massacre.

REFERENCES

Bailey, Paul.1957. Wovoka, the Indian Messiah. Los Angeles, CA: Westernlore Press.

Du Bois, Cora. 1939. The 1870 Ghost Dance. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Mooney, James. 1965. The Ghost-Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Osterreich, Anne Shelley. 1991. The American Indian Ghost Dance, 1870 and 1890: An Annotated Bibliography. NY: Greenwood Press.

Posting Date:

December, 2011