PRINCE PHILIP TIMELINE

1966: Iounhanen villagers presented a pig to British Resident Commissioner Alexander Mair Wilkie during his visit to Tanna. Wilkie died on August 13 of that year and did not reciprocate.

1971 (March): Prince Philip briefly visited the New Hebrides, including Malakula island, on the Britannia.

1973-1974: Freelance journalist Kal Müller filmed island life (kava drinking, dancing, circumcision ceremony) and John Frum rituals and convinced Iounhanen men to revive wearing penis wrappers and to consider establishing a kastom (custom) school for their children to attend.

1974 (February 15-17): Prince Philip, Queen Elizabeth, and Princess Anne visited the New Hebrides on the royal yacht Britannia. They did not call at Tanna. Jack Naiva of Iounhanen claimed he canoed out to the Britannia in Port Vila harbor and saw the Prince in a white uniform.

1975 (November 10): The first general election in the colonial New Hebrides took place. The anglophone New Hebrides National Party won seventeen seats.

1977 (November 29): The second general election, boycotted by the Vanua’aku (National) Pati (Party), took place. The Vanua’aku Pati declared a People’s Provisional Government in areas it controlled.

1977 (March): The General Assembly was suspended after the Vanua’aku Pati boycott.

1978 (September 21): British Resident Commissioner John Stuart Champion visited Iounhanen village and learned of the unreciprocated pig. He obtained a framed photograph of Prince Philip and five clay pipes and returned to Iounhanen to present these gifts.

1978: Tuk Nauau carved a pig-killing club that British authorities sent to Buckingham Palace. The Palace returned a second photograph of Prince Philip wielding the club and newly appointed British Resident Commissioner Andrew Stuart visited Iounhanen to present this second photograph.

1979 (November 14): Third general elections in the New Hebrides. The Vanua’aka Pati won twenty-five out of thirty-nine seats.

1991: Movement co-founder Tuk Nauau was featured in the 1991 documentary The Fantastic Invasion, filmed with a Prince Philip photograph hanging behind.

2000: Buckingham Palace sent another photo of Prince Philip to Tanna

2007 (September): Posen and four other men from Iakel village were featured in the television reality show Meet the Natives. Prince Philip welcomed them off camera to Buckingham Palace and gifts (including another photograph and a walking stick) were exchanged.

2009: Other Iakel villagers were featured in the American version of Meet the Natives.

2009: Movement co-founder Jack Naiva died.

2014 (October): Princess Anne visited Port Vila.

2015: Iakel villagers wearing penis wrappers and bark skirts, and Iakel village itself, starred in Tanna, a feature film nominated in 2017 for a Best Foreign Language Academy award.

2018 (April): Prince Charles visited Port Vila. Jimmy Joseph, from Iounhanen, gave him a walking stick.

2021 (April 9): Prince Philip died.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

When Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, [Image at right] died on April 9, 2021, obituaries celebrated his long life, his faithful support of his wife Elizabeth, his military career, and his witty if sometimes gruff personality. They also noted that he was a “South Pacific Island God” (see Drury 2021; Morgan 2021; among many others), and was revered as such on Tanna Island in southern Vanuatu. This apotheosis was a journalistic exaggeration, a not untypical misunderstanding of island actuality. The Prince was not a god. Rather, he was an island brother, the son of Kalpwapen a powerful spirit who lives atop Tukusmera, the highest mountain on the island. Young Philip, somehow, had found his way to Europe to marry a queen. But he had returned several times to the islands and clever pundits from a few isolated villages were delighted to reestablish a relationship (or a “road,” in local parlance) with him. The renewed connection was marked with exchanges of gifts including photographs and clay pipes from the Prince, and clubs, walking sticks, and pigs from his island relatives. [See, Doctrines/Beliefs below]

Tanna island is appreciated by anthropologists, linguists, and tourists alike for both its rich cultural and linguistic traditions that have survived, if somewhat transformed, 250 years of culture contact and for remarkable religious and social innovations, the John Frum movement among the best known of these (Lindstrom 1993). The Duke fit usefully into island politics of the 1970s. France and Great Britain, in 1906, established the New Hebrides Condominium colony after neither would agree which power would occupy this island chain. By the 1970s, Southwest Pacific colonies were achieving independence, beginning with Fiji in 1970. By the mid-1970s it was clear that New Hebridean independence, too, was quickly approaching and this sparked much political competition between the two ruling powers, concerned to transfer authority to a friendly independent government, and confrontational dispute and debate among islanders themselves.

The colonial education system was never good, but more islanders had attended British funded schools, and spoke some English, than had matriculated in French schools. The French were particularly concerned to beef up support for francophone and French-leaning political parties that competed in several national elections: a first in 1975 for a new General Assembly; a second, failed election, in 1977; and a third in 1979 for what would become the rechristened Vanuatu’s first Parliament. In these years both the British and French sent operatives around the archipelago to discuss impending independence, explain voting procedures, and firm up political support (Gregory and Gregory 1984:79). The French especially cultivated John Frum movement supporters, headquartered at east Tanna’s Sulphur Bay, with a range of enticements. The British, in counterpoint, established relations with a few isolated villages in the west that, conveniently, had just rediscovered their lost brother, the Duke of Edinburgh. Then British Resident Commission Andrew Stuart denied any ulterior political motive in these dealings (Stuart 2002:497), but doubts justifiably persist.

West island Iounhanen village, and neighboring Iakel, located about five km up the mountainside from the colonial administrative headquarters although isolated by bad trails and tracks, had hosted in the early 1970s freelance photographer Kal Müller. Müller managed to convince villagers to doff their tattered shorts and skirts and resume wearing traditional men’s penis wrappers and women’s bark skirts. Villagers also discussed establishing a kastom (“custom”) school in which their children could learn island traditions (Baylis 2013:36). This exotically much improved an article that Müller published in the National Geographic (1974). It also boosted the villages’ attraction for a small, but growing number of tourists that came to Tanna. Bob Paul, an Australian trader resident on Tanna since 1952, had helped establish a small airline that connected Tanna with the main national airport on Efate Island, and built Tanna’s first tourist bungalows. He arranged for visitors to climb Iasur, the island’s active volcano, drive by a herd of “wild horses,” and tour Sulphur Bay, John Frum movement headquarters. Some tourists also began calling at Iounhanen to take part in traditional dance ceremony and hobnob with real kastom villagers, as signified by those penis wrappers and bark skirts.

Paul’s connections with Iounhanen were good, and he and British island agent Bob Wilson facilitated British Resident Commission John Champion’s visit to that village in September, 1978. People there, Champion wrote, unlike John Frum supporters were “basically well-disposed to the British” (2002:153). Villagers in 1966 had presented Alexander Wilkie, one of Champion’s predecessors, a pig and some kava (Piper methysticum). They now complained that Wilkie (who died soon after this visit) had never reciprocated these gifts. Leading men Jack Naiva and Tuk Nauau requested some return token, preferably from Champion’s London boss, the Prince. Naiva may have observed Philip, dressed in naval whites, on the Britannia during its royal visit to Port Vila in 1974. He claimed he had canoed out into Vila harbor to scrutinize the yacht (Baylis 2013:60). Gender relations on Tanna remain patriarchal and male princes trump female queens, particularly one in an impressive uniform. A return gift would square the exchange and promise enduring international connections after the British departed, which they did when the colony achieved independence in 1980.

The British Residency consulted Kirk Huffman, the Anglo-American curator of the New Hebrides Cultural Centre in Port Vila, who explained the cultural significance of reciprocal exchange and noted men’s continuing fondness for German-produced clay pipes, a popular nineteenth century trade item (Baylis 2013:56). Champion contacted Buckingham Palace which provided a signed photograph of the Duke. He then returned to Iounhanen with photograph and five clay pipes that Naiva and Nauau received “with great dignity and satisfaction, although one old man was heard to mutter that it would have been even better if HRH had come in person” (Champion 2002:154).

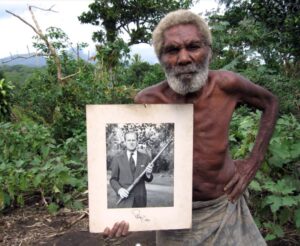

Nauau, in turn, gave Champion a pig-killing club that he had carved and asked that this be sent to the Prince and a photograph of Prince-with-club be taken. This was done and Andrew Stuart, who replaced Champion as British Resident Commission at the end of 1978, brought this second photograph down to Iounhanan (Gregory and Gregory 1978:80). The British, from the beginning of it all, were well-aware of the public relations potential of these exchanges and they recruited BBC photographer Jim Biddulph to film the gift exchange. (Biddulph missed the exchange itself but subsequently took the first, now famous, image of Naiva holding the picture of Philip with club (Stuart 2002:498)). [Image at right]

Photographs, books, and other paper material have short lives on Tanna given the island’s tropical climate and passing cyclones, and the Palace over the years continued to send along replacement photographs as earlier ones decayed, including one in 2000 accompanied by a Union Jack flag.

Iounhanen and Iakel in the 1970s were small, isolated, and sparsely populated places made remote by bad roads and mountain slopes. In the 1920s, the Presbyterian mission (the nearest mission station located at Ateni village (Athens)) had converted people; and in the 1940s, people abandoned the mission to join the resurgent John Frum movement. These villages, though, were on the margins of both Christian and John Frum organizations and people enjoyed little recognition or respect from their island neighbors, let alone from the wider world. They could, and did, however, boast their commitment to true island kastom. Naiva’s and Nauau’s brilliant idea, which has much elevated their fame and fortunes, and erased their marginality, was to create a kastom road to Prince Philip.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Most islanders, although largely Christian, maintain a firm belief in the presence of spirits, and they share a rich set of myth motifs with fellow Melanesians and with Polynesian neighbors in the central Pacific. One common motif concerns two brothers, one of whom leaves home while the other stays behind (Poignent 1967:96-97). A chain of myths along the northern coast of Papua New Guinea, for example, recount the stories of separated brothers Kilibob and Manup (Pompanio, Counts, and Harding 1994). The brothers are culture heroes who, with superhuman power, innovated or introduced important elements of culture. One is often credited with establishing local traditions, and the other, who disappeared beyond the horizon, with endowing colonizing Europeans with the technological and other powers they enjoy. Prince Philip, as a long-lost island brother, fits into this widespread Melanesian myth motif.

More particularly, the Duke also served island and colonial politicking in the 1970s as a British counterweight to the French-leaning John Frum movement, and as a well-placed brother who might elevate Iounhanen’s local renown. Tanna, with its oral culture, is an island of competing and overlapping stories. Sacred texts are not codified in print. People are inspired constantly with messages that they receive in dreams, or when slightly intoxicated by kava, infusions of which men drink together every evening (when supplies permit) at village dance/kava-drinking grounds (Lebot, Merlin, and Lindstrom 1992). Since the 1970s, many variant Prince Philip tales have circulated about Tanna and have been spread widely by international journalists delighted to recount the Duke’s delicious, if incorrect, apotheosis.

Resident Commission Champion heard some early stories in 1978, although these no doubt were warped through British ears: The Duke is a son of mountain spirit Kalpwapen; John Frum is his brother; he

had flown across the sea, where he married a white lady, and would one day return in his nambas [penis wrapper] to live on the volcano and rule over them in perpetual bliss—when old men would lose their wrinkles, become young and strong again, and be able to enjoy the favours of innumerable women without restraint (2002:153-154).

Andrew Stuart, his successor, added that “Some said that, in his white naval uniform, he must be the pilot of John Frum’s aeroplane” (2002:497). Other early stories promised Philip several nubile young wives when he came home to Tanna.

These accounts correlate with Western appreciation of the John Frum movement as a “cargo cult” (Lindstrom 1993). These were social movements, widespread in Melanesia, that erupted after the Pacific War Prophets instructed followers to improve their behavior and repair their social relationships so as to invite ancestral spirits, or American cargo planes and ships, to return with material wealth, political salvation, better health, and even immortality.

Tuk Nauau is a better source for island stories. Huffman, when photographs were first exchanged in 1978, interviewed Nauau and others to provide background intelligence to the Palace. In Fantastic Invasion Nauau lauds the creation of new roads, new connections as with the Prince, that will ensure peace and prosperity. His stories connect Tanna to the wider world which the Prince represents (Baylis 2013:17). Nauau holds up a cupro-nickel coin, silver joined with copper, or in island eyes black with white. The coin, like the Duke, symbolizes happy relationships that profitably conjoin families together (Baylis 2013:122-23).

The label “cargo cult,” which most anthropologists began to avoid by the 1970s, shaded and simplified diverse post-war Melanesian social movements. Prince Philip’s Tanna following was not a cargo cult despite journalistic unquenchable fondness for the term. A 2017 television series that commemorated James Cook’s Pacific voyages showcased “The Prince Philip Cargo Cult” (Lewis 2018; see also Davies 2021 and many others). Instead, the Prince from afar looks after his island relatives, enhancing their lives on Tanna. Islanders looked forward to an eventual reunion with their roving brother, and not so much to the treasure or cargo that he might bring home. They expected his homecoming which has, with his passing, indeed occurred. Philip’s spirit is back on Tanna.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Innovative Philip stories did not spark much new ritual in either Iounhanen or Iakel. Instead, followers incorporated recognition of the Prince within the normal round of island ceremony. This includes daily communion with spirits during evening kava consumption, and standard circle dances (nupu) that mark important events (marriages, the circumcision of sons, and annual exchanges of first-fruit yams and taro). Iounhanen and Iakel hosted a large regional pig-killing festival (nekoviar or nakwiari) in the 1970s and they might do so again in some future commemoration of the Duke.

Baylis, who visited Iouhanen for a month in 2005, was disappointed not to discover specific celebratory rites. Naiva explained “We don’t sing songs to Prince Philip. We don’t go into a special house. We don’t have . . . sticks like this”—he made the sign of the cross with his hands—“or dances or anything like that” (2013:235). That sort of ostentatious ritual, Naiva explained, was something that Christians and John Frum followers did and it merely “blocks the road.” Philip’s island brothers instead,

…walk slowly. We work in the gardens. We drink kava. We keep it in our hearts. And what happens? Prince Philip sends us photographs and letters. We have built a road, and because we continue to do it our way, the kastom way, and not the way of the Christians and the John people, one day men from Tanna will meet him” (2013:236).

Naiva stored his two Philip photographs in a structure raised off the ground, out of reach of pigs and floods (Baylis 2013:200), and he curated a small collection of Philip letters and published articles inside his house.

Ongoing journalistic attention and tourist arrivals (before Covid19 disrupted these) recently have encouraged innovation of ceremonial occasions, including the Duke’s June 10 birthday, although Islanders are fitful time-keepers. Iakel supporters, when informed of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s wedding, reportedly raised one of their British flags, drank kava, and danced nupu (Lagan 2018). Followers also gathered to kill and share pigs, and drink kava, to mourn Philip’s death when they heard the news. Traditionally, male relatives of a dead kinsman grow their beards out for about a year and then organize a mortuary feast to mark shaving these off. Such celebrations are ad hoc and irregular, sparked largely by passing external attention.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Leadership on Tanna is diffuse and contextual (Lindstrom 2021). Men occupy managerial positions insofar as others are willing to follow. At the village level, numbers of men claim one or the other of two sorts of traditional chiefly titles (ianineteta “spokesman of the canoe” and ierumanu “ruler”) although in practice age, experience, and ability determine who effectively serves as “chief.” Regional organizations (the many Christian denominations active on the island; John Frum; previous groups including “Four Corner” and various Kastom churches; and now the Prince Philip movement) operate similarly. Able, typically older, men (particularly those who receive innovative messages from spirits or the wider world) command followings.

Jack Naiva and Tuk Nauau, along these lines, were two principal innovators of Prince Philip stories. They took advantage of the politically troubled 1970s, an unreciprocated pig, a fortunate encounter with the Britannia during its 1974 royal visit to Port Vila, and a community unhappy with its marginality to evoke a hidden princely connection. Nauau, who suffered from filariasis, died in the 1990s and Naiva in 2009. Movement leadership has passed to a second generation, but even before Naiva died serious conflict had erupted between the Duke’s followers in Iounhanen village and those in Iakel, located a few hundred yards down the road and led by Johnson Kouia, Posen, and others. Such denominational conflict is typical on the island as communities and organizations dispute and split over resources. In this case, the Prince and the global attention he commanded, and a growing tourist business, were the main points of conflict.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Philip is dead. What might islanders do next? Much journalistic speculation focused on whether Prince Charles might take his father’s place in the hearts of the Tannese (e.g., Squires 2021). No firm story, however, has yet appeared that Charles will supplant Philip. Philip’s spirit, after all, is now back home on Tanna [Image at right] and he continues to offer roads that lead out into the wider world.

A bigger challenge comes from the movement’s remarkable success. This precipitated a split between Iounhanen and Iakel, which deepened when the latter captured much of the tourist trade. Although Iounhanen, in the 1970s, was first to offer itself to the world as a kastom village tourist attraction (and villagers could hurry to don their penis wrappers and bark skirts when a truck could be heard grinding up the mountain trail), Iakel by the 2000s had captured much of the trade (Connell 2008). Iakel men also starred in both the British (2007) and American (2009) versions of the reality television show Meet the Natives. This carried five villages to the U.K. and the U.S. where they met new friends and encountered exotic Western social conditions (homeless people, for example). The Duke, in the British version (episode three, part five), entertained the five Iakel men in Buckingham Palace, although off camera. They gave Philip several gifts including another walking stick, and apparently asked him “Is the pawpaw ripe yet or not?” If ripe, his return to Tanna was imminent. One wonders about the Duke’s willingness to hobnob with his followers although this did enhance international relations as is his assigned island duty.

In 2015, Iakel villagers in their penis-wrappers and bark skirts starred in an Australian-produced feature film, Tanna (Lindstrom 2015). This film, in 2017, was nominated for an Academy Award Best Foreign Language Film, and it won other awards including one from the African-American Film Critics Association. Its young stars traveled widely to international film festivals. The Prince, too, popped up in the film as village elders commend his arranged marriage with Elizabeth as an essential model for island marriages which are also still mostly arranged by a couple’s parents (Jolly 2019).

Tourist visits to Tanna increased significantly in the 2000s, before Covid-19 closed borders. Vanuatu’s National Statistics Office reported that over 11,000 international visitors came to Tanna in 2018. Most arrived to tour Iasur, the island’s volcano, but increasing numbers also paid to experience and photograph kastom life in Iakel, or in several competing villages hawking island traditionalism. A few, especially wide-eyed journalists, come to follow Prince Philip’s trail. When international tourism resumes, this growing outlandish attention promises to deepen island conflict as Philip’s followers clash over the money and other resources that visitors offer.

Philip has indeed served as the road along which villagers have, like him, left Tanna to travel far. Now that his spirit is back home on the island, his road may one day become overgrown and impassable, replaced by new connections and new global relationships that islanders crave. But, for now, his stories still circulate, and his light which shines on Tanna continues to attract the world to this remote and fascinating island.

Image #1: Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburugh.

Image #2: Jack Naiva with Philip’s photograph (a post-1978 retake).

Image #3: Map of Tanna.

REFERENCES

Baylis, Matthew. 2013. Man Belong Mrs Queen: Adventures with the Philip Worshippers. London: Old Street Publishing.

Champion, John. 2002. John S. Champion CMG, OBE. Pp. pp.142-54 in Brian J. Bresnihan and Keith Woodward, eds. Tufala Gavman: Reminiscences from the Anglo-French Condominium of the New Hebrides. Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific.

Connell, John. 2008. “The Continuity of Custom? Tourist Perceptions of Authenticity in Yakel Village, Tanna, Vanuatu.” Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 5:71-86.

Davies, Caroline. 2021. “Prince Philip: The unlikely but willing Pacific deity.” The Guardian, April 10. Accessed from https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/apr/10/prince-philip-south-sea-island-god-duke-of-edinburgh on 1 August 2021.

Drury, Colin. 2021. “Prince Philip: Tribe Who Worshipped Due as God Will Wail to Mark His Death.” Independent, April 10. Accessed from https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/royal-family/prince-philip-death-island-tribe-b1829458.html on 1 August 2021.

Gregory, Robert J. and Janet E. Gregory. 1984. “John Frum: An Indigenous Strategy of Reaction to Mission Rule and the Colonial Order.” Pacific Studies 7:68-90.

Jolly, Margaret. 2019. Tanna: Romancing Kastom, Eluding Exoticism? Journal de la Societe des Oceanistes 148:97-112.

Lagan, Bernard. 2018. “Royal wedding: Duke cult islanders celebrate with a feast.” The Times, May 21. Accessed from https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/duke-cult-islanders-celebrate-with-a-feast-kmxjbkxqb on 1 August 2021.

Lebot, Vincent, Mark Merlin, and Lamont Lindstrom. 1992. Kava: The Pacific Drug. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lewis, Robert. 2018. The Pacific in the wake of Captain Cook with Sam Neill. (study guide). St Kilda: Australian Teachers of Media.

Lindstrom, Lamont. 2021. Tanna Times: Islanders in the World. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Lindstrom, Lamont. 2015. Award-winning film Tanna sets Romeo and Juliet in the south Pacific.” The Conversation, November 4. Accessed from http://theconversation.com/award-winning-film- tanna-sets-romeo-and-juliet-in-the-south-pacific-49874 on 1 August 2021.

Lindstrom, Lamont. 1993. Cargo Cult: Strange Stories of Desire from Melanesia and Beyond. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Morgan, Chloe. 2021. “South Pacific Yaohnanen tribe who worship Prince Philip as a God believe his spirit is ready to return to their island to bring ‘peace and harmony to the world’—and say Prince Charles will ‘keep their faith alive’.” Daily Mail, April 20. Accessed from https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-9487967/Vanuata-island-tribe-worship-Prince-Philip-God-believe-spirit-ready-return-home.html on 1 August 2021.

Müller, Kal. 1974. “A Pacific Island Awaits Its Messiah.” National Geographic 145:706-15.

Poignant, Roslyn. 1967. Oceanic Mytholody: The Myths of Polynesia, Micronesia, Melanesia, Australia. London: Paul Halyn.

Pompanio, Alice, David R. Counts, and Thomas G. Harding, eds.1994. Children of Kilibob: Creation, Costom and Culture in Northeast New Guinea. Pacific Studies (special issue) 17:4.

Squires, Nick. 2021. “Spiritual secession: Vanuatu tribe who worshipped Prince Philip as a god will now deify Charles.” The Telegraph, April 9. Accessed from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/royal-family/2021/04/09/spiritual-succession-islanders-worshipped-prince-philip-god/ on 1 August 2021.

Stuart, Andrew. 2002. “Andrew Stuart CMG CPM.” Pp. 588-506 in Brian J. Bresnihan and Keith Woodward, eds. Tufala Gavman: Reminiscences from the Anglo-French Condominium of the New Hebrides. Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific.

Publication Date:

4 August 2021