MARPINGEN TIMELINE

1858: St. Bernadette reported a series of apparitions in Lourdes, France.

1868: Margaretha Kunz, Katharina Hubertus and Susanna Leist were born in Marpingen.

1870-18/71: The French-German War took place and the German Empire was established.

1875: The first organized pilgrimage from Germany to Lourdes took place.

1876 (July 3): At Lourdes, a statue in honor of the Virgin was consecrated.

1876 (July 3): Margaretha, Katharina and Susanne saw a figure in white in the forest.

1876 July): There was an imitation of the Marpingen apparition by children in Poznan (Prussia).

1877: An apparition of Mary in a medicine bottle was discovered close to Koblenz.

1877 (September 3): The apparitions stopped abruptly.

1878 (January 16): A debate about Marpingen was held in the Prussian lower house.

1879: A trial against nineteen individuals took place in Saarbrücken.

1883: Elisa Recktenwald claimed a new apparition.

1889: Margaretha revealed the apparitions were “one big lie.”

1932: A chapel was built at the site where Mary appeared.

1999: New apparitions occurred in Marpingen.

2005: The bishop of Trier declared that the supposed apparitions of 1876-1877 and 1999 were not confirmed by the church.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The apparitions of Mother Mary in the German village Marpingen originated with three girls and their families. On Monday, July 3, 1876, the adult population of the village was engaged in haymaking. Since this work was too difficult for children, the eight year-old girls, Margaretha Kunz (1868-1905), Katharina Hubertus (1868-1904) and Susanna Leist (1868-1884) were sent out to pick berries in the nearby forest, called Härtelwald. [Image at right] As they were turning to go home, after the Angelus sounded before dawn, one of the three saw a white figure, which was confirmed by the two others. At home they shared their experience with their parents, who were skeptical initially. They might have seen a woman from the village, the father of Susanna Leist suggested. His wife ordered the girls: “Go back into the woods tomorrow, pray, and if you see her again ask who she is; if she says she is the Immaculately Conceived, then she is the Blessed Virgin.” The girls did what they were asked, and they soon the figure was identified as the Virgin Mary. Families and neighbours became more and more convinced, all the more as Mary began to appear more often to the girls.

There were some miraculous cures, and the visionaries invited the villagers to follow them to the place in the Härtel-forest and to touch the feet of the Mother of God in order to be cured. The pride of the girls, who suddenly stood in the centre of the community’s interest, and the Marian piety of the villagers went hand in hand to broaden interest in the events. Within days, Catholics from neighbouring locations were attracted, and pilgrims from the Saarland and even places much further away visited Marpingen. Some estimated 20,000 visitors in the first week, exceeding the numbers of Lourdes in 1876. July and August of 1877 saw between 600 and 1,200 believers daily taking communion in the parish church. Finally, the apparitions stopped on September 3, 1877.  The three visionaries and their families were removed from Marpingen in May 1878, and they were required to stay in the Convent of the Poor Child Jesus in Echternach, Luxembourg.

The three visionaries and their families were removed from Marpingen in May 1878, and they were required to stay in the Convent of the Poor Child Jesus in Echternach, Luxembourg.

Social, social-psychological, cultural and other context are critical to understanding the Marian apparitions at Marpingen. In the 1870s, Marpingen was a poor, small village of 1,600 inhabitants in the Saarland, the western part of Germany. Located twenty-five kilometers north of Saarbrücken, the secluded place became the center of Marian interest in 1876. [Image at right]

Economically, Germany experienced a Great Depression beginning in 1873 (Gründerkrach), which didn’t leave Marpingen untouched. The village was impoverished enough and could not live on its own agrarian products. Most farmers were poor goat peasants. During the week, the men had to earn extra wages in the mines outside the village. The farmer-miners were complaining about low wages in these years, since the mines also paid a price for the economic depression. The economic crisis was accompanied by a serious religious and political crisis: The culture war (Kulturkampf) between state and church reached its peak in the mid-1870s. Marpingen was close to the border of France, which longed for revenge for the lost war and Alsace- Lorraine. [Image at right] This was not the only transnational aspect of the story, since Lourdes and the tendencies toward standardization of Marian devotion in the wake of ultramontanism turned out to be crucial for the apparitions in Marpingen. Thus, there were plenty of reasons for villagers to be fearful, to complain and to imitate role models which were successful abroad.

Lorraine. [Image at right] This was not the only transnational aspect of the story, since Lourdes and the tendencies toward standardization of Marian devotion in the wake of ultramontanism turned out to be crucial for the apparitions in Marpingen. Thus, there were plenty of reasons for villagers to be fearful, to complain and to imitate role models which were successful abroad.

The apparitions met the expectation that in times of crisis the Blessed Virgin would give comfort. Her appearance also made villagers hope to profit from the positive commercial effects of becoming a prominent place of pilgrimage. Marpingen hoped to become the “German Lourdes.”

The apparitions at Marpingen also had an important gender dimension. Because most able-bodied men worked in the mines during the week, the population of Marpingen on those days predominantly consisted of women, children, and old men. Wives were left alone to run the village. Marian apparitions fell on fruitful ground in this female context. This was the situation when the first apparitions started on Monday, July 3, 1876. Until the next Friday there were five days in which the situation dramatized without the working men. The first supporters of the apparitions were women like Katharina Leist, while her husband, who was sick and retired and thus in Marpingen, wiped the thing away as some misconception. On the second evening, twenty children and six women, from the families or neighbours, gathered in the Härtel-forest. Men only appeared on July 5. They included the father of Katharina Hubertus, the publican, the schoolteacher, and later that evening Nikolaus Recktenwald, an unemployed miner suffering from rheumatism. After the children told him to touch Mary’s foot, he felt that he had been cured. This miracle was of considerable importance in shaping the opinion of the villagers as was the fact that men of reputation on that evening approved the apparition claims of the three children. Nevertheless, the role of the local women in nursing the cult remained central. Women also comprised the vast majority of the pilgrims, which can be understood in the wider context of the feminization of Catholic piety during the nineteenth century.

The situation in Marpingen had many collateral effects. The wish to profit from adult attention drove some other children in 1877 to claim Our Lady has also appeared to them. These “rival children,” though, were unable to gain any of the prominence of the three original seers. The satirical journals took full advantage of the events. Apparitions of the Holy Virgin were imitated in other places like in Poznan (Prussia), where in 1877 Polish children claimed to have seen her. Variations of Marpingen became popular. For example, people saw an apparition of Mary in a medicine bottle filled with water from Marpingen that was located in the window of a house. This attracted more than 5.000 pilgrims in the area close to the city of Koblenz.

In the years and decades after 1877, the number of pilgrims fell to a handful daily. Even the claim of Elisa Recktenwald in 1883 (one of the “rival children” of 1877) that Our Lady had appeared to her could not slow the downturn. The complaint and message from Mary to her was “Have I not appeared already to so many children? Yet so few have believed.” There was a new peak of pilgrims in the early years under Adolf Hitler and another one in the post-war years. A visitors-book of 1947 shows that the average number of visitors to the chapel was as high as twenty-two a day.

Another brief revival of Marian apparition claims emerged in the late 1990s. Between May and October 1999, three women again claimed to have had contact to Mary, although they reported different experiences. Marion Guttmann, a thirty year-old housewife, reported seeing her; Christine Ney, who was twenty-four and learning musical education, reported hearing her; and Judith Hiber, who was thirty-five and an assistant in law, reported to badly hear and badly see her. None of them was from Marpingen, however, and community inhabitants were skeptical about the “humbug.”

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The apparitions in Marpingen lacked any kind of special doctrine or belief, rather they were a typical manifestation of the pious fashion concerning Our Lady in the nineteenth century, one which incorporated all the typical ingredients which had emerged since the beginning of the century. Earlier Marian phenomena were reported by men, mostly priests, while in the nineteenth century it was women and children who dominated the scene. Classic Marian cults like Guadalupe in Spain or Czestochowa in Poland, both originating in the fourteenth century, dealt with miraculous objects attracting adoration.

The rejuvenated cultic activity in the nineteenth century was centred around apparitions of the Virgin Mary herself, often revealing messages or admonitions, such as to pray more frequently. After these sorts of apparitions happened to Cathérine Labouré in a cloister in Paris (1830/1831) and to two young cowherds in La Salette (1846) during a famine, the most famous event involved Bernardette Soubirous in Lourdes (1858). Finally, all the necessary elements of the modern Marian apparition were complete: the simplicity of the female, young visionary, a message, miraculous cures, the sceptical reactions of the parish priest and over-reacting civil authorities. The new type of Marian apparitions in the nineteenth century was “a French creation” (Blackbourn 1995:4). The apparitions of the Blessed Virgin in Lourdes provided a transnational text to refer to from different angles: for Catholics as a blueprint, for national liberals as a sign of lacking national loyalty. Catholics explicitly hoped to establish a “German Lourdes” in Marpingen. The international charisma of Lourdes appeared infectious. But how could Margaretha, Katharina and Susanne know about this blueprint? How could eight year-old girls contribute to the standardization of Marian devotion in Europe? Their parents and older sisters (one of them wanted to become a nun) and the teacher in primary school were dwelling in Marian piety, and the local priest Jakob Neureuter preached about the apparitions in Lourdes. The French events were a major topic in the media during these years, especially since the first organized German pilgrimage to Lourdes in 1875. The whole village was deeply immersed in Marian adoration. Soon after the apparitions, Catholic newspapers discussed the “German Lourdes,” the “Rhenish Lourdes,” the “second Lourdes,” or the “Bethlehem of Germany.”

Part of the standardization of Marian cult was that most messages delivered by her were quite similar to those uttered in Lourdes and other places: To pray more. Prophecies of the girls were hardly touching major issues like war or starvation, but rather local situations. One of the visionaries later confessed: the people asked for miracles and so we gave them some. Some messages were adapted to Marpingen if the situation required it. The priest, who went after the girls in order to observe them, was informed that the Virgin did not want him to follow the girls. Another message addressed the commercial interests of Catholic merchants. The Blessed Virgin, as a rumor in Marpingen went round, instructed people, “not to shop any longer with the Jews,” some of whom were traders and lived in the neighboring Tholey.

Another part of this standardization was that Mary no longer appeared in colourful clothes anymore but rather in white or blue. After the three girls have learned that they met the Immaculately Conceived, the visions were constantly “improved” and “corrected” by the parents. It was the parents, not the children, who reported a blue sash that Mary was wearing, a detail known from the role model in Lourdes. Many ideas were simply proposed to the children who just agreed to the suggestions. When the children were asked whether the Virgin was carrying a golden Crown and Jesus in her arm, the children readily agreed. The Marpingen Mary more and more resembled the one in Lourdes.

The messages of Our Lady in 1999 were given to the three female seers, who recorded them, and when Mary was gone, the cassette was played to the excited audience. One of the messages was: “It is all in my plan for this place to grow together. Do not be afraid, my children. Trust, trust with all your heart; and place your fears and needs in my Immaculate Heart.” Though the messages were quite minor (to pray along the rosary, to stop abortion and to obey the pope), thousands came to participate in the events, which happened only on weekends. Church services were offered for the public in the chapel, which was built in 1932, and thousands went to the near-by dwell which they believed to contain holy water. Hermann-Joseph Spital, the bishop of Trier, forbade talk about “apparitions” and about the “visionaries.” Instead, acceptable discussion should be about “events in the Härtel-forest.” Marpingen is a place where Mary continues to be worshiped.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Soon after the initial apparitions, women from the village went to the place of the apparitions in the forest to place flowers. People came from near and far to participate in the phenomenon. The most compelling reason to go there was the prospect of miraculous healing. People who were blind, deaf, rheumatic, arthritic, or who suffered from the consequences of typhoid or smallpox, went to the site of the apparitions. They repeated the prescribed prayers while their hands were guided to the spot where the Virgin supposedly appeared. Some were disabled and arrived in wheelchairs, hoping for grace and cure. Many visitors were welcomed to stay overnight in private rooms, since Marpingen was hard to reach. The nearest train station was located in St. Wendel, seven kilometers away. The business of quartering boomed, and the taverns were full.

In the first days after July 3, 1876 about 4,000 people visited the site; in the second week of the apparitions 20,000 people came to Marpingen. Since that time, people came more frequently on weekends or for Marian festivals. They received communion and went to the site of the apparitions in order to pray. There was a final wave of pilgrims in the phase between July and September 1877, sometimes reaching 9,000 pilgrims a day, because the Holy Virgin had announced that she was ending her visits. Especially on the predicted last days of the apparitions during the first three days of September 1877, there were 30,000 visitors. In her last appearance Our Mary reportedly said: “I will be back in hard times”.

Most also drank the miraculous water in the Härtel-forest. The water from the dwell near the apparitions was believed to have miraculous potential and was sold for consumption by the needy. A pilgrim from Trier filled a twelve liter jug and carried it home by foot in February 1877. Not only the villagers profited. Retailers from outside Marpingen opened ambulant shops in order to sell devotional objects.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Many famous sites of pilgrimage in the nineteenth century were gathering places, such as the pilgrimage to the Holy Robe in Trier 1844 or Lourdes since 1858. Many organizations formed or were involved in bringing the pilgrims in such places. Marpingen is an example of the opposite. The movement came from below. There was no ecclesiastical architecture which supported the events and no hierarchical institution which could evaluate the evidence of the apparitions. Marpingen belonged to the diocese of Trier. During the culture war between state and church (Kulturkampf), which raged between 1871 and 1878, the bishop of Trier, Matthias Eberhard, was arrested in 1874. Thus, the diocese was left without a bishop. Eberhard died in May 1876, shortly before the apparitions in Marpingen began. It was not until 1881 before a new bishop was elected, Michael Felix Korum. Also, there was no dean in St. Wendel, the deanary responsible for Marpingen. The church suffered losses not only on the top level but also on the level of ordinary staff. Many priests were arrested or, if they had died, were not replaced by a new one because, among other things, the state asked for an official state exam in higher education (Kulturexamen), which the church refused. Of the 731 parishes of the diocese, 230 were without leadership.

The position of Jakob Neureuter, the parish-priest who supervised his flock in Marpingen since 1864, was particularly stressful. He personally believed in the apparitions but was ecclesiastically required to be cautious until an official investigation approved them. But without a bishop there was no official investigation of the type that the bishop of Regensburg could initiate for the apparitions in Mettenbuch (1876). Neureuter was left alone in keeping the collective emotions under control, standing between the emphatic expectations of his flock, the regulations of the church, and the hostility challenging his village from outside.

In the absence of a bishop in Trier, Johann Theodor Laurent (1804-1884), Apostolic Vicar in Luxembourg and titular bishop of Chersones, was asked to write a report on the apparitions. He uttered serious doubts about them, about Mary’s “frequent changes of dress,” and of her words, which often were only a “mere aping” of Lourdes. He suggested that perhaps everything was a diabolical delusion, since the visionaries also met Lucifer sometimes. The bishop played a crucial role in the fact that the apparitions at Trier were never approved.

The pilgrims, who flooded Marpingen, represented lower social status groups; the bourgeoisie, such as academics (Bildungsbürger) and upper status businessmen (Wirtschaftsbürger) was missing. Some wives of the Catholic nobility were committed, most prominent among them: Princess Helene of Thurn und Taxis, and in 1877 the mother of the Bavarian King and the sister of the Austrian Kaiser.

The apparitions and religious worship in Marpingen, as in many places, were part of a strong wave of Marian apparitions that occurred during the Italian and German unification wars in the decade between 1866 (Philippsdorf) and 1877, with a peak around 1870 in Italy and in Alsace. The events and their consequences were not isolated phenomena but rather were national and transnational. Embedded in European texts and contexts, Marpingen both resulted from previous apparitions in other places in other countries and also inspired new apparitions in different places. Marian apparitions were communicated beyond borders and sparked off new events. For example, when a statue in honour of the Virgin was consecrated in Lourdes, 100,000 Catholics were present, among them thirty-five bishops and 5,000 priests. This event happened on July 3, 1876, the very same day when 894 kilometres away from Lourdes three girls in the Härtel-forest reported seeing a white figure during early evening.

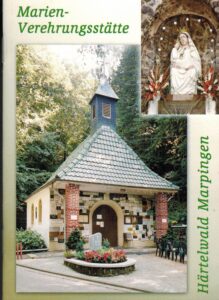

The (missing) church hierarchy in Trier and the centre of ultramontane adoration, Rome, played a minor role in the events in Marpingen. A correspondent from the Berlin Catholic newspaper “Germania” wrote an article in the “Civiltà Cattolica,” promulgating the consecration of a chapel at the place of the apparitions. It was not until 1932 that private initiative lead to the erection of a Marian chapel for pilgrims at the site of the apparitions. [Image at right] All of this occurred during years that saw dramatic unemployment in the region. The authorities of the church in Trier refused to consecrate the chapel because they didn’t want to encourage superstition. Some elderly women in 1934, 1935 and 1937 tried to move the situation forward by claiming to have seen Mother Mary. While the church labeled them “hysterical women,” the flow of pilgrims to Marpingen grew again during the regime of National-Sozialism. In the post-war years and through the 1950s, there was pressure from pious agitators who tried to convince the ecclesiastical hierarchy to consecrate the chapel but they failed. A consecration, which would have been an official approval of the visions, has never happened.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Ten days after the first apparition, armed infantry invaded the village expelling the pilgrims with means of force. Some people were seriously injured, and access to the forest was closed. But neither the army nor the additional gendarmes, who were sent to Marpingen to control the situation and to seal the area where the pilgrims gathered, could stop the Holy Virgin. Now she appeared in barns and houses within the village. The army occupied the village for a couple of weeks. Authorities interviewed the people involved. Among those examined were the parish-priest Jakob Neureuter and the visionaries.

Catholic and liberal newspapers across Germany reported the events from different angles. While Catholic newspapers emphasized the status of the villagers as victims, the liberal position surmised a clerical complot behind the events. For them Catholics were superstitious and nationally not reliable. They considered the gathering of thousands of people as a case of breach of the public peace. The parish priest and several villagers were arrested and put on trial. The three girls, who started it all, were the subjects of intense interrogations. Nevertheless, the events extended into the year 1877.

Marpingen had to pay a high price for wishing to become a “German Lourdes” and to improve the low community income by means of becoming a centre for pilgrims. The events had a serious aftermath. The penalties included that the village was liable to pay 4,000 marks for hosting troops it never asked for, and also that the investigations involved hundreds of people, villagers and priests. On January 16, 1878, the conduct of the army and bureaucracy in Marpingen was discussed prominently in the Prussian lower house. Members of the Centre party had tabled a motion, calling for reimbursement of the 4,000 marks, the rescinding or the ban to enter the Härtel-forest, and disciplinary measures against the officials involved.

The most serious cases against agitators involved led to a legal tribunal. In the beginning, the investigations concentrated on sedition, riotous assembly, and breach of the peace. After realizing that these accusations were untenable, investigators moved to accuse individuals of fraud and deception. The trial against nineteen individuals started in March 1879 in Saarbrücken with 170 witnesses against the defendants and only twenty-six supporting them.

In both cases, before trial and in parliament, the prominent attorney Julius Bachem was one of the fiercest defenders of the Catholic case, not in the sense that he believed in the apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Marpingen, but in the social and legal sense and because he belonged to the same Catholic milieu. At the end, the motion in Parliament was denied, but in court none of the nineteen people charged was convicted.

Later avowals of Margaretha Kunz reveal that they probably only had seen stacked-up wood with the white side pointing outwards. But it was half-dark, and Susanna Leist’s outcry “Grechten, Kätchen, look, over there is a women in white” frightened them and created a collective suggestion. The “great mistake” had been “to believe us immediately instead of calming us down.” It was all “one big lie,” Margaretha confessed in 1889. But as they were climbing in the hierarchy of respect among the villagers, as reporters and priests idolized them, they enjoyed their growing prominence and kept playing the role expected from them.

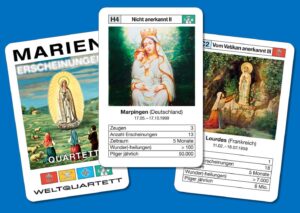

Marpingen continues to attract some individual pilgrims who worship Mother Mary. After some years of investigation, the bishop of Trier, Reinhard Marx, declared in 2005 that neither the supposed apparitions of 1876 nor those of 1999 were confirmed by the church. The chapel was never consecrated. Marpingen never made it to become the “German Lourdes.” But the Marpingen-Mary of 1999 made it at least into a quartet with the topic Marian apparitions (“the most glamorous appearances of the Holy Virgin in 32 playing cards”), even if only in the category: “not approved.”

IMAGES

Image #1: The three seers of 1876 (photo: Stiftung Marpinger Kulturbesitz).

Image #2: Stielers Karte von Deutschland in 25 Blatt, Gotha 1875.

Image #3: Section of the Map containing Marpingen.

Image #4: Gregor Hinsberger, Marien-Verehrungsstätte Härtelwald Marpingen, Marpingen, 2003.

Image #5: Marpingen and Lourdes in the quartet of Weltquartett, Hamburg.

REFERENCES

Blackbourn, David. 1995. Marpingen. Apparitions of the Virgin Mary in a Nineteenth-Century German Village. New York: Vintage.

Blackbourn, David. 2007. Marpingen. Das deutsche Lourdes in der Bismarckzeit. Saarbrücken: Association for the Promotion of the Saarbrücken State Archive.

Blaschke, Olaf. 2020. “Vom ‘Kulturkampf‘ an der Saar bis zum ‘Burgfrieden‘ (1870–1918).” Pp. 255-86 in Reformation, Religion und Konfession an der Saar (1517–2017), edited by Gabriele Clemens and Stephan Laux. Saarbrücken.

Blaschke, Olaf. 2020. “Pilgrimages, Modernity, and Ultramontanism in Germany.” Pp. 166-89 in Nineteenth-Century European Pilgrimages: A New Golden Age, edited by Antón M. Pazos. Abingdon.

Blaschke, Olaf. 2016. “Marpingen: A Remote Village and its Virgin in a Transnational Context.” Pp. 83-107 in Roberto di Stefano and Francisco Javier Ramón Solans (Hg.), Marian Devotions, Political Mobilization, and Nationalism in Europe and America. Houndmills: Palgrave MacMillan.

Rebbert, Joseph. 1877. Marpingen und seine Gegner. Apologetische Zugabe zu den Schriften und Berichten über Marpingen, Metenbuch und Dittrichswalde. Ein Schutz- und Trutzbüchlein für das katholische Volk. Paderborn.

Schneider, Bernhard. 2008. Ein “deutsches Lourdes”? Der “Fall” Marpingen (1876 und 1999) und die Elemente eines kirchlichen Prüfungsverfahrens. Pp. 178-99 in Maria und Lourdes. Wunder und Marienerscheinungen in theologischer und kulturwissenschaftlicher Perspektive, edited by Bernhard Schneider. Münster.

Publication Date:

15 March 2021