JEHOVAH’S WITNESSES IN RUSSIA TIMELINE

1891: Charles Taze Russell visited Kishinev (now Chișinău).

1911: Charles Taze Russell visited L’viv.

1928: George Young, Bible Student missionary, traveled to Soviet Union.

1949: Operation South secretly deported Witnesses from Soviet Moldavia.

1951: Operation North secretly deported Witnesses from western borderlands of Soviet Union.

1957: Jehovah’s Witnesses worldwide signed a petition to the Soviet government asking for end to persecution.

1965: Jehovah’s Witnesses were released from special exile.

1991: The Soviet Union granted registration to Jehovah’s Witnesses organization.

1992: Russia granted registration to Jehovah’s Witnesses organization.

1997: The Russian government passed the law “On Freedom of Conscience and Religious Associations” that implemented stricter regulation of religious groups.

2002: The Russian government passed the law “On Combatting Extremist Activity” that implemented broad measures to combat extremism, including by religious groups.

2004: Moscow Jehovah’s Witnesses were barred from registration within city limits.

2009: Jehovah’s Witness publications began to be declared extremist and banned.

2017: The Russian Supreme Court liquidated the Russian organization of Jehovah’s Witnesses.

2019: The first Jehovah’s Witness in post-Soviet Russia was sentenced to prison for religious reasons.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Founder Charles Taze Russell [Image at right] preached in the Russian Empire as part of his broader global missionary outreach in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Jehovah’s Witnesses: Proclaimers, 1993:406). A few interested Russian subjects requested copies of his publications, and wrote letters to his organization. Still, interest in his message did not lead to a sustained missionary presence in the Russian Empire (Baran 2014:16).

In the interwar period, sporadic attempts at evangelism within Soviet borders continued (Young 1929:356-61). Soviet hostility to religion made it impossible for Witnesses to establish any official or organized presence. Meanwhile, the Witnesses attracted significant converts in Eastern Europe just across the Soviet Union’s western borders. The situation for these communities changed dramatically as a result of World War II. During this period, the Soviet Union annexed territories along its western borders, including the countries of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, and portions of Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia. These territories contained thousands of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Soviet annexation made them Soviet citizens overnight (Baran 2014:14-30).

Soviet Witnesses showed remarkable dexterity in adapting to challenging conditions and surviving decades of persecution. Without the ability to establish Kingdom Halls, they met in small groups in private homes, often at odd hours to avoid detection. Baptisms were likewise done in secret, typically in local rivers and lakes (Baran 2014:119-20). Large gatherings were rare, but some communities found ways to discretely hold outdoor events under various guises. While the international organization established a country committee to oversee Soviet operations, it kept this leadership structure confidential to avoid the arrest and imprisonment of members. A small number of Witnesses illegally smuggled in religious literature from abroad, duplicating it either by hand or with private printing equipment. Courier networks then distributed this literature to members (2008 Yearbook 2008:144-52). As such, Bible Studies and meetings typically did not have the same circulation and discussion of a regularly rotating set of magazines and tracts as is typical in other countries. Evangelism took on creative approaches, and depended less on door to door methods. Witnesses tended instead to seek out opportunities to share their faith in less formal settings with neighbors, coworkers, and strangers, even as these actions carried substantial risk (2008 Yearbook 2008:106-07).

Despite such conditions, Witnesses managed to maintain a steady following in the Soviet Union. While it is difficult to calculate the exact membership, tens of thousands of adult Soviet citizens belonged to the Witnesses in the postwar period. Their membership was heavily concentrated in the western borderlands, and also in and around sites of exile and imprisonment throughout the Soviet Union. Most Witnesses lived in rural locations, and most had only a basic education and worked in agriculture or unskilled professions. In large part, this demographic situation reflects the Soviet state’s discriminatory policies against religious believers in the workforce and at universities (Baran 2014:113-14).

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991, Jehovah’s Witnesses experienced rapid growth and sudden freedom in Russia. Witnesses now enjoyed legal protections to  safely evangelize to their neighbors, publish and circulate literature used by Witnesses worldwide, rent and buy property for Kingdom Halls, [Image at right] and hold larger gatherings of Witnesses across the country. As of 2017, the organization counted roughly 175,000 active members. Nearly double that number attended meetings or Bible studies (Baran 2020:2).

safely evangelize to their neighbors, publish and circulate literature used by Witnesses worldwide, rent and buy property for Kingdom Halls, [Image at right] and hold larger gatherings of Witnesses across the country. As of 2017, the organization counted roughly 175,000 active members. Nearly double that number attended meetings or Bible studies (Baran 2020:2).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The Watch Tower organization teaches that only Jehovah’s Witnesses are faithful to Christianity as taught by Jesus and practiced by the early apostles. They believe that every other interpretation of Christianity but their own is erroneous.

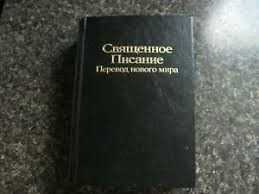

Jehovah’s Witnesses regard the Bible as the ultimate source of authority and justify all of their doctrines and beliefs with reference to scripture. They regard the Bible as inerrant. Witnesses do not interpret the entire Bible literally, regarding parts of it as metaphorical or symbolic. In 1961, a committee of Watch Tower translators completed a version of the Bible that is used by Witnesses worldwide. Witnesses consider the New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures the most accurate translation of the Bible. Unlike other versions of the Bible, it consistently renders the name “God” as “Jehovah” and refers to the  Old and New Testaments as the “Hebrew-Aramaic Scriptures” and the “Christian Greek Scriptures.” This Bible is translated into other languages from the English-language version, including a Russian translation in 2007 (2008 Yearbook 2008:237). [Image at right] The English version is regularly updated and the most recent edition appeared in 2013 (Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society 2013).

Old and New Testaments as the “Hebrew-Aramaic Scriptures” and the “Christian Greek Scriptures.” This Bible is translated into other languages from the English-language version, including a Russian translation in 2007 (2008 Yearbook 2008:237). [Image at right] The English version is regularly updated and the most recent edition appeared in 2013 (Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society 2013).

Witnesses believe that Jesus was the only begotten son of God but, since he was begotten, deny any scriptural basis for the Trinitarian doctrine that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit together form one Godhead (Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society 2013: 2-3). They believe that the Kingdom of God is a government in heaven (Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society 1953:113-126). This Kingdom will soon replace worldly governments and carry out God’s will upon the earth. Witnesses regard this event as imminent and teach that humanity is living in the “last days,” citing 2 Timothy 3:1-5 and Matthew 24:3-14, hence the urgency of spreading their message (Knox 2018:111-115).

Witnesses teach that Jesus cast Satan out from heaven and that Jesus began ruling the Kingdom of God in 1914. Upon their death, only 144,000 people (known as the “anointed class” or the “little flock”) will dwell in the Kingdom of Heaven, where they rule with God and Jesus Christ. Most of the 144,000 have already taken their places in heaven. Witnesses believe that the rest of the faithful (known as the “the great crowd”) will live through Armageddon and then enjoy paradise on earth during the millennial rule of Christ. If they have already died before Armageddon, they will be resurrected after the battle to live in this millennial kingdom (Knox 2018:33)

Life in the eternal paradise will be open to all who decide to live “in the truth,” as they call it. The dead will be raised during the millennium and judged. Those who do not attain salvation simply pass out of existence forever. Jehovah’s Witnesses do not believe in hell as a place of fiery punishment, but rather consider it the common grave for all mankind. They do not believe in purgatory. When people die, they are in an unconscious state, much like dreamless sleep.

Jehovah’s Witnesses do not venerate the cross or any other Christian symbol or image. The organization teaches that Jesus died on a wooden stake, rendered as “torture stake” in the New World Translation.

Witnesses abide by the laws of governments, except in cases where they believe that state law contradicts Jehovah’s law. Although they aspire to be law abiding, they will continue to meet under ban or refuse to fulfill national military service because Jehovah’s law takes precedence. The belief that the Bible teaches they ought to stand aloof from worldly affairs means they do not engage with ideological or political issues. They do not stand for public office and refuse to fight in wars.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Baptism is a precondition to attaining everlasting life (Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society 1958:472-478). Only youths and adults can be considered by elders for baptism. They must undertake a period of guided Bible study using Watch Tower literature as study aids, before they are accepted as one of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Baptism is by full water immersion. Witnesses have wedding celebrations and funerals in much the same way as other Christian faiths.

There is only one event on the Witnesses’ religious calendar: the Memorial, also known as the Lord’s Evening Meal (Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society 2003:12-16). Witnesses gather in their congregations to listen to elders give a Bible talk and to watch them distribute the “emblems,” as the bread and wine representing the body and blood of Christ are known. Only members of the anointed class consume the bread and wine at the Memorial service (usually there are none in a congregation) (Chryssides 2016:217-220).

Jehovah’s Witnesses do not celebrate Christmas or Easter, and regard them as pagan practices. Occasions that venerate the individual rather than Jehovah are banned, hence Witnesses do not celebrate birthdays or Mother’s Day. They do not celebrate patriotic holidays, salute the flag, or sing national anthems since this would be to profess allegiance to a secular government (Knox 2018:61-106).

While weekly meeting schedules have changed over the faith’s history, as of 2020, Witnesses meet at a Kingdom Hall with other members of their congregations twice a week, for around two hours. The program of the meeting is determined by the Governing Body, as is the literature Witnesses must read in preparation for it. Members of the congregation listen to elders speak, participate in Bible study sessions, and train for ministering to the public. Even young children are expected to remain attentive during these meetings. Witnesses undertake Bible study at home at least one evening a week, sometimes with other Witnesses from their congregations as guests. Their discussions are closely guided by publications from the organization, including the Watchtower magazine and a monthly bulletin focusing on ministry, among others, all of which are available on its website.

Every able Witness is expected to minister, most notably through door-to-door evangelism. In the past decade, they have become highly visible by standing with literature carts in busy thoroughfares and on city streets. Those who are too frail are encouraged to witness to the extent that they are able, which might be over the telephone or by writing letters, or through what the organization calls “informal witnessing.” The time Witnesses spend “in the field,” as they call it, is reported to elders, who pass the information up to the central organization. It compiles these statistics into figures for every country, which feed into worldwide statistics, which are publicly available on the Jehovah’s Witnesses website.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Witnesses regard the ultimate authority on interpreting the Bible on all matters, sacred and profane, as the Governing Body. The Governing Body is a group of men based at the worldwide headquarters in upstate New York. The number of members has fluctuated, but has always been between seven and eighteen. The men are appointed, rather than elected. Facilitating its governance are six committees, each led by a chairman serving a one-year term: the Coordinators’ Committee; Personnel Committee; Publishing Committee; Service Committee; Teaching Committee; and Writing Committee. Between them, these six committees direct all of the organization’s activities around the world.

The Governing Body’s teachings are transmitted to rank-and-file Witnesses through clearly defined levels of regional, national, local, and congregational authority. The leadership roles and organizational hierarchy is detailed in the book Organized to do Jehovah’s Will, designed for use within congregations to define the structure of and to clarify the sources of authority within the organization (Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania 2019).

The elders carry the authority within the congregation and are responsible for, among other things, disciplining Witnesses found to have committed serious offences. If a Witness has ignored or flouted the teachings of the Governing Body and, after meeting a judicial committee, is regarded as unrepentant, they may be “disfellowshipped,” meaning they are no longer considered one of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Other Witnesses, including those in their congregation, are required to shun them. This may include members of their own family. The congregations also have “ministerial servants,” who are primarily concerned with the day-to-day functioning of the community, such as financial matters, literature stocks, and so on. In addition, each congregation has three categories of pioneers who dedicate a different amount of time to ministry: auxiliary pioneers, fregular pioneers, and special pioneers (Knox 2018:41-47).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Soviet laws narrowly restricted which religious organizations could register with the state and legally operate on Soviet soil. Without registration, Witnesses had no legal standing. They did not have the right to conduct worship services or Bible studies, evangelize to others, or import and distribute religious literature (Walters 1993:3-30). For nearly all of Soviet history, any organized activities by Jehovah’s Witnesses were considered violations of Soviet law and subject to criminal prosecution.

The most severe persecution of Witnesses occurred under the rule of Joseph Stalin, who oversaw mass arrests of Witnesses in the years immediately following World War II. In 1949 and 1951, the Soviet state exiled nearly all Witnesses from the western borderlands to remote outposts in the Soviet interior. This “special exile” included both the elderly and children, and was done in secret. Families had no warning, lost nearly all of their possessions, and had to adjust to difficult conditions in isolated regions (Neizvestnyi Stranitsy Istorii 1999; Odintsov 2002).

After Stalin, the state eventually released Witness communities from special exile, and most imprisoned Witnesses received sentence reductions and early release. In the decades that followed, most Witnesses did not suffer arrest or imprisonment, but they did face steady harassment and job discrimination. Arrests, though relatively rare, did occur, especially for young men who refused to complete military service. Some Witnesses lost custody of their children (Baran 2014:77-82, 180-86).

Perhaps the biggest and most enduring challenge for Soviet Witnesses was one of state scrutiny and public perception. The Soviet Union’s attitude toward Jehovah’s Witnesses was consistently hostile. Soviet publications repeatedly referred to Witnesses as “sectarians,” framing them as a fringe group far outside the mainstream (Baran 2019:105-27). This led the public to view Witnesses as dangerous, unpatriotic, and anti-social. State hostility was based on several factors. First and foremost, Witnesses did not comply with many of the state’s basic expectations for its citizens. They did not complete mandatory military service, a matter of particular importance given the recent worldwide conflict that had cost the Soviet Union millions of lives, and the ensuing Cold War. They also did not vote in elections, a requirement of all Soviet citizens. In addition, Witnesses kept apart from state-run organizations, including trade unions and youth organizations affiliated with the Communist Party.

Further, the Witnesses’ organizational structure made them vulnerable to accusations of divided loyalties. On a basic level, the Witnesses were (and remain) headquartered in the United States, the Soviet Union’s Cold War rival. State propaganda accused Witnesses of harboring secret loyalties to a foreign power. Moreover, the Witnesses continued to illegally import and distribute religious literature produced in the United States, which frequently contained Cold War rhetoric against the Soviet Union (Knox 2018:257-62).

For the Soviet state, the Witnesses’ actions went beyond the requirements of private religious belief and directly threatened state control over its citizens. As such, the state expended significant resources into attempting to convince or coerce Witnesses into abandoning their faith, or at least into modifying their specific practices to avoid violations of the law. Witnesses were frequently subjected to intense public pressure. Newspapers trumpeted the alleged misdeeds of individual believers. Atheist agitators approached Witness families to share antireligious tracts and convince them to join mainstream society. Teachers pressured Witness children to join extracurricular activities. They also browbeat parents into allowing their children to wear Young Pioneer scarves and attend Pioneer events (Baran 2014:128-31).

Overall, Witnesses were severely marginalized in the postwar Soviet Union, and did not enjoy any freedom to practice their faith without fear of harassment or persecution.

In March 1985, when Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary of the Communist Party, and therefore leader of the USSR, Russian Jehovah’s Witnesses operated entirely underground and at great personal risk. Gorbachev introduced far-reaching reforms in the years following his accession, dramatically altering conditions for Russian Witnesses. One element of his reform programme was “glasnost,” usually translated as “openness,” which permitted the acknowledgment, discussion, and debate of previously taboo topics, among them the repression of religion in the USSR and the stranglehold of the one-party state over cultural and spiritual life. As a result of Gorbachev’s commitment to pluralism and tolerance, religious life was, gradually at first and then at swift pace, liberated from state repression and control (Ramet 1993:31-52).

As for many other religious communities, this degree of freedom was unprecedented for Russian Witnesses. Administrative processes and legislative procedures soon caught up, and Jehovah’s Witnesses were able to legally register in the Ukrainian republic on February 28, 1991 and in the Russian republic on March 27, 1991. With this, Russian Witnesses could meet for Bible Study in private homes, hire venues for larger meetings, maintain contact with Witnesses abroad (including the worldwide headquarters) and preach their beliefs openly, all without fear of state reprisal. When the Soviet Union collapsed in December 1991, Witnesses in the Russian Federation, one of the USSR’s successor states, retained their newfound freedoms. New legislation on religious life allowed Witnesses, and other religious groups, both Russian and foreign, a wide range of rights (Knox 2012:244-71).

In the immediate post-Soviet period, the resurgence of faith, in all of its varieties, concerned Russia’s ideologically conservative and nationally-oriented political, cultural, and religious elites. The leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church, Russia’s majority faith, argued that it needed an opportunity to reach Russians confused by the seismic socioeconomic shifts that accompanied the period of transition from communism to capitalism without being in competition with wealthier religious groups more experienced in outreach, charitable work, and missionizing (Bourdeaux and Witte 1999). The Church lobbied for restrictions on religious freedom, resulting in the federal law “On Freedom of Conscience and Religious Associations,” passed in 1997. The law, which has been subject to comprehensive analysis, sought to marginalize non-traditional religious communities and ensure the dominance of Russian Orthodoxy in post-Soviet society (Knox 2005:2-4; Baran 2007:266-68). It cast foreign religious organizations such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses as interlopers. The Putin regime’s increasingly nationalistic and authoritarian tendencies meant that foreign religious groups came to be regarded with suspicion and even contempt by the government, lawmakers, and cultural elites.

The Russian state’s treatment of Witnesses led to multiple cases before the European Court of Human Rights, which upholds rights in the member states of the Council of Europe. The first of these was in 2007, when the Court ruled in favor of Konstantin Kuznetsov and 102 other Witnesses in Kuznetsov and Others v. Russia. The Court found that local authorities had illegally disrupted a meeting of hearing impaired Witnesses in Cheliabinsk. Three years later, the Court again upheld the rights of Russian Witnesses in Jehovah’s Witnesses of Moscow v. Russia after the Moscow City Prosecutor’s Office banned the Watch Tower organization in the capital (Baran 2006). A third relevant ruling against Russia centered on Article 8 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (the European Convention on Human Rights), on the right to privacy. The Court ruled that city officials in St. Petersburg committed rights’ violations when they ordered the disclosure of confidential medical information about two Witness patients who refused a blood transfusion (Avilkina and Others v. Russia, 2013). A fourth case, Krupko and Others v. Russia (2014), resulted from a raid on a Memorial celebration in Moscow in 2006, when Witnesses were under ban in the city. Several Witnesses were detained. The Court found in favor of Jehovah’s Witnesses, awarding them money for damages and legal expenses (Knox 2019:141-43).

In 2002, the federal law “On Combatting Extremist Activity,” known simply as the “extremism law,” was introduced in response to terrorist attacks on Russian apartment buildings in 1999. Although ostensibly introduced to eliminate radicalism, Russian authorities used it to restrict the rights of oppositional or radical groups, secular and religious. Human rights activists and international observers widely criticized the law for its broad definition of extremism, which included anti-social views and offensive statements, even those without any violent content (Baran and Knox 2019; Verkhovsky 2009). In 2009, a Witness community in Taganrog was dissolved on the grounds that it was extremist, a decision upheld in the regional court at Rostov. In 2014, congregations in Samara and Abinsk were dissolved under the same pretext. The following year, numerous other regions followed suit, leading to a clear sense that the net was closing in on the national organization.

In 2017, the Russian Supreme Court banned the administrative body of Jehovah’s Witnesses under the extremism law. The federal case against Witnesses centered on statements made in Watch Tower literature rather than on Witness activities in Russia. The prosecution alleged that the organization’s claim that Witnesses are the sole bearers of Biblical truth denigrated the country’s traditional religious faiths. As a result, Watch Tower literature was added to the Federal List of Extremist Materials, a database of banned works maintained by the Ministry of Justice. The Watch Tower organization’s official web site (www.jw.org) is on the list and is blocked by Russian internet providers. Also in 2017, Russian federal prosecutors banned the New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures. It was declared extremist by a court in Vyborg, a ruling later upheld by the regional court.

The 2017 ruling effectively led to the liquidation of this religious community in Russia. It dissolved the Administrative Center of Jehovah’s Witnesses in Russia (the national headquarters) [Image at right] and all of the congregations registered under its auspices. The state confiscated the organization’s property. Authorities seized the national headquarters, a large property on the outskirts of St Petersburg. In addition to these legal moves against the organization, ordinary Witnesses have faced violence and intimidation across the country, from arson attacks on Kingdom Halls to loss of their jobs. Russian Witnesses are no longer able to legally meet, even in small groups in their own homes. Any evangelism is considered extremist activity and a criminal offense. Russian courts have charged some Witnesses with extremist activity for allegedly continuing organized religious activity after the ban went into effect. Some have been found guilty and sentenced to terms in labor camps. Witness activity is also forbidden in China, Egypt, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Iraq and in the former Soviet republics of Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan. In this respect, the 2017 ruling aligns Russia with some of the world’s most repressive regimes (Knox 2019).

As of 2020, Witnesses continue to face persecution, imprisonment, and harassment across the country. The Watch Tower organization issues regular press releases on the sentencing of Russian Witnesses for practicing their faith, efforts to overturn the ban in the European Court of Human Rights, and the condemnation of the ruling by legal scholars, religious rights activists, and foreign governments (Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society 2020). Until the ban is lifted, Russian Witnesses will continue to operate underground, as they did in the Soviet period, directed by the worldwide headquarters and aided by an expansive network of resilient communities who have adjusted to these difficult circumstances.

IMAGES

Image #1: Charles Taze Russell.

Image #2: The former Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, June 27, 2014.

Image #3: Russian translation of the New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures.

Image #4: The former Russian administrative centre of Jehovah’s Witnesses.

REFERENCES

Baran, Emily B. 2020. “Written Testimony on Religious Freedom in Russia and Central Asia.” U.S. Commission on International Religio.us Freedom.

Baran, Emily B. and Zoe Knox. 2019. “The 2002 Russian Anti-Extremism Law: An Introduction.” The Soviet and Post-Soviet Review 46:97-104.

Baran, Emily B. 2019. “From Sectarians to Extremists: The Language of Marginalization in Soviet and Post-Soviet Society.” The Soviet and Post-Soviet Review 46:105-27.

Baran, Emily B. 2014. Dissent on the Margins: How Soviet Jehovah’s Witnesses Defied Communism and Lived to Preach About It. New York: Oxford University Press.

Baran, Emily B. 2007. “Contested Victims: Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Russian Orthodox Church, 1990-2004.” Religion, State and Society 35:261-78.

Baran, Emily B. 2006. “Negotiating the Limits of Religious Pluralism in Post-Soviet Russia: The Anticult Movement in the Russian Orthodox Church, 1990-2004.” Russian Review 65:637-56.

Chryssides, George D. 2016. Jehovah’s Witnesses: Continuity and Change. London: Routledge.

Jehovah’s Witnesses: Proclaimers of God’s Kingdom. 1993. Brooklyn: Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of New York, Inc. and International Bible Students Association.

Knox, Zoe. 2019. “Jehovah’s Witnesses as Extremists: The Russian State, Religious Pluralism, and Human Rights.” The Soviet and Post-Soviet Review 46:128-57.

Knox, Zoe. 2018. Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Secular World: From the 1870s to the Present. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Knox, Zoe. 2012. “Preaching the Kingdom Message: The Jehovah’s Witnesses and Soviet Secularization.” Pp. 244-71 in State Secularism and Lived Religion in Soviet Russia and Ukraine, edited by Catherine Wanner. New York: Oxford University Press.

Odintsov, M. I. 2002. Sovet ministrov SSSR postanovliaet: “Vyselit’ navechno!” Moscow: Art-Biznes-Tsentr.

Neizvestnye stranitsy istorii: po materialam konferentsii “Uroki represii.” 1991. Chita.

Ramet, Sabrina Petra. 1993. “Religious Policy in the Era of Gorbachev.” Pp. 31-52 in Religious Policy in the Soviet Union, edited by Sabrina Petra Ramet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Verkhovsky, Alexander. 2009. “Russian Approaches to Radicalism and ‘Extremism’ as Applied to Nationalism and Religion.” Pp. 26-43 in Russia and Islam: State, Society and Radicalism, edited by R. Dannreuther and L. March. London: Routledge.

Walters, Phillip. 1993. “A Survey of Soviet Religious Policy.” Pp. 3-30 in Religious Policy in the Soviet Union, edited by Sabrina Petra Ramet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society. 2020. “Russian Court Imposes Two-Year Suspended Sentence on Brother Konstantin Bazhenov, His Wife, and a 73-Year-Old Sister.” Official Website of Jehovah’s Witnesses, September 25. Accessed from https://www.jw.org/en/news/jw/region/russia/Russian-Court-Imposes-Two-Year-Suspended-Sentence-on-Brother-Konstantin-Bazhenov-His-Wife-and-a-73-Year-Old-Sister/ on 19 October 2020.

Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania. 2019. Organized to do Jehovah’s Will. Walkill, NY: Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania.

Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society. 2013. New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures. Brooklyn, NY: Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society.

Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society. 2013. “Should You Believe in the Trinity?” Awake!, August 13, pp. 2-3.

Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society. 2008. 2008 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Brooklyn, NY: Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of New York, Inc.

Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society. 2003. “Why Observe the Lord’s Evening Meal?” The Watchtower, February 15, pp. 12-16.

Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania. 1976. 1977 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses. New York City: Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of New York, Inc.

Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society. 1958. “Baptism.” The Watchtower, August 1, pp. 472-78.

Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society. 1953. “When Will God’s Kingdom Come?” The Watchtower, February 15, pp.113-26.

Witte Jr, John and Michael Bordeaux, eds. 1999. Proselytism and Orthodoxy in Russia: The New Wars for Souls. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Berezhko, Konstantyn. 2005. Istoriia Svidkiv Egovy na Zhitomyrshchyni. Zhytomyr: Zhytomyrs’kyy Derzhavnyy Universytet im. Ivana Franka.

Chryssides, George D. 2019. Historical Dictionary of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of New York. 2001. “Faithful under Trials: Jehovah’s Witnesses in the Soviet Union.” Brooklyn, NY: Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of New York.

Gazhos, V.F. 1969. Osobennosti ideologii iegovizma i religioznoe soznanie sektantov. Kishinev: Redaktsionno-izdatel’skii otdel akademii nauk Moldavskoi SSR.

Gol’ko, Oleg. 2007. Sibirskii marshrut. Third Edition. Moscow: Bibleist.

Gordienko, N.S. 2000. Rossiiskie Svideteli Iegovy: Istoriia i sovremennost. Saint Petersburg: Tipografiia pravda.

Iarotskii, P.L. 1981. Evoliutsiia sovremennogo Iegovizma. Kiev: Izdatel’stvo politicheskoi literatury Ukrainy.

Ivanenko, Sergei. 1999. O liudiakh, nikogda ne rasstaiushchikhsia s Bibliei. Moscow: Art-Biznes-Tsentr.

Ivanenko, Sergei. 2002. Svideteli Iegovy: Traditsionnaia dlia Rossii religioznaia organizatsiia Moscow: Art-Biznes-Tsentr.

Knox, Zoe. 2020. “Russian Religious Life in the Soviet Era.” Pp. 60-75 in Oxford Handbook of Russian Religious Thought, edited by Caryl Emerson, George Pattison, and Randall A. Poole. London: Oxford University Press.

Moskalenko, A.T. 1961. Sekta iegovistov i ee reaktsionnaia sushchnost. Moscow: Vyshaia shkola.

Pasat, V.I. 1994. Trudnye stranitsy istorii Moldovy. Moscow: Terra.

Rurak, Pavel. 2008. Tri aresta za istinu. L’viv: Piramida.

Publication Date:

15 November 2020